Abstract

Very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency can present at various ages from the neonatal period to adulthood, and poses the greatest risk of complications during intercurrent illness or after prolonged fasting. Early diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance can reduce mortality; hence, the disorder is included in the newborn Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) in the United States. The Inborn Errors of Metabolism Information System (IBEM-IS) was established in 2007 to collect longitudinal information on individuals with inborn errors of metabolism included in newborn screening (NBS) programs, including VLCAD deficiency. We retrospectively analyzed early outcomes for individuals who were diagnosed with VLCAD deficiency by NBS and describe initial presentations, diagnosis, clinical outcomes and treatment in a cohort of 52 individuals ages 1–18 years. Maternal prenatal symptoms were not reported, and most newborns remained asymptomatic. Cardiomyopathy was uncommon in the cohort, diagnosed in 2/52 cases. Elevations in creatine kinase were a common finding, and usually first occurred during the toddler period (1–3 years of age). Diagnostic evaluations required several testing modalities, most commonly plasma acylcarnitine profiles and molecular testing. Functional testing, including fibroblast acylcarnitine profiling and white blood cell or fibroblast enzyme assay, is a useful diagnostic adjunct if uncharacterized mutations are identified.

Keywords: Very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, Fatty acid oxidation disorder, Newborn screening, Rhabdomyolysis, Inborn errors of metabolism, Natural history

1. Introduction

Very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency is a disorder involving the initial step of fatty acid beta-oxidation in the mitochondrial matrix. The deficient enzyme is encoded by the gene ACADVL [1, 2]. The prevalence of VLCAD deficiency is estimated at 1:30,000 to 1:100,000 births [3], [4]). The disorder can present at various ages from the neonatal period to adulthood, and poses the greatest risk of complications during intercurrent illness or after prolonged fasting. Symptoms can include hypoglycemia, rhabdomyolysis, skeletal muscle weakness, and cardiomyopathy. Multiple genotypic variants have been described in patients with VLCAD deficiency, and some genotypephenotype correlations have been reported [5–8]. Treatment emphasizes avoidance of fasting and often includes a specialized diet that is low in long chain fats and supplemented with medium chain triglycerides (MCT). Carnitine is sometimes prescribed, but its use is controversial [9]. Additional novel therapeutic agents are currently under investigation [10–14]. Recognizing that morbidity and mortality related to VLCAD deficiency can be reduced with early diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance, this disorder is included in the newborn Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) in the United States [15].

While VLCAD deficiency was described over 20 years ago [2], limited information is available regarding long-term outcomes in affected individuals, especially those identified through newborn screening. A recent report of 32 cases indicated that the majority of those identified by NBS were asymptomatic at diagnosis and remained so during seven years of follow up [4]. Those who were diagnosed while symptomatic had complications that included cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, skeletal myopathy, and hypoglycemia [4]. Significant long-term symptoms have been reported in patients identified both symptomatically and through newborn screening. Improvement in these symptoms with the use of the investigational drug triheptanoin has been reported [10, 14], but not with bezafibrate [16].

The Inborn Errors of Metabolism Information System (IBEM-IS) is a robust data collection tool used to collect demographic and longitudinal clinical information from patients with inborn errors of metabolism and their clinicians at metabolic specialty centers in multiple states. In this study, the IBEM-IS was used to retrospectively analyze early outcomes for infants who were diagnosed with VLCAD deficiency following positive NBS. Initial presentations, diagnostic testing, maternal complications, cardiac outcomes and dietary treatment are described in a cohort of 52 individuals who participate in the IBEMIS. We addressed the following key questions in our data review:

What symptoms do the majority of individuals exhibit at diagnosis or develop later in childhood? The majority of previously published case series for individuals with VLCAD deficiency reports on individuals who are symptomatic. Our cohort presented a unique opportunity to study clinical outcomes in individuals diagnosed early in life through NBS.

Can molecular testing help to resolve pitfalls in diagnosis? We recognize the existence of overlap of biochemical analytes for VLCAD deficiency in affected and unaffected individuals and thus explored the utility of genotyping for diagnostic purposes [17].

Do maternal complications occur during pregnancy? Acute fatty liver in pregnancy and other complications have been described in women carrying fetuses affected with long-chain FAOD [18–21]. We explored whether this was an observed complication for VLCAD deficiency.

Is there variability in the specific treatment modalities used for VLCAD deficiency? Treatment modalities for VLCAD deficiency can be variable and are based on expert opinion [3] but evidencebased treatment protocols are greatly needed. We analyzed treatment approaches for affected patients, including diet, supplements and sick day management.

2. Materials and Methods

IBEM-IS subjects were included in this study if they had a diagnosis of VLCAD deficiency and were ascertained by abnormal newborn screening. Eligible cases enrolled between March 2007 and November 2014 were included, and data entered into the IBEM-IS through December 15, 2015 were queried. For each individual meeting these criteria, available data regarding diagnostic evaluation, pregnancy, cardiac evaluations, and dietary management at initial and interval visits were obtained for analysis. “Intake” was defined as the time the child was first entered into the IBEM-IS database. Data reported as having occurred prior to that time were thus reported retrospectively. Serial “interval” data referred to post-intake data from the interval between the prior and most recent clinic evaluations. “Neonatal” symptoms were those reported by the center to occur in the neonatal period. The IBEM-IS data dictionary specifies that the neonatal period spans the first 28 days of life. “Initial evaluation” symptoms were those reported at the first metabolic evaluation after the abnormal newborn screen results were known (and may have occurred in the first month of life or later).

The data set analyzed for this study did not include direct or indirect identifiers or protected health information from any subject in the database. The study was reviewed and granted an exemption by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Investigations at Duke University. Data were tabulated and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software version 23.0. Analysis of most parameters consisted of frequency tabulation and descriptive statistics of data collected. Values for C14 and C14:1 acylcarnitines from NBS samples were compared using Independent Samples Mann Whitney U Test. Conflicting or unclear information was clarified with the originating center via the IBEM-IS Coordinating Center, Michigan Public Health Institute. Genotype information was collated. For variants not previously published in publicly available databases or in the literature, we utilized several open source prediction software programs (Mutation Taster, www.mutationtaster.org; SIFT, http://sift.jcvi.org/) to annotate pathogenicity. Ensembl transcript ID ENST00000356839 served as the reference sequence (accessed December 8, 2015).

Molecular modeling was performed on a Silicon Graphics Fuel workstation (Mountain View, CA) using the Insight II 2000 software package (Dassault Systèmes, BIOVIA Corp – formerly Accelrys Technologies, San Diego, CA) and the published atomic coordinates of recombinant human VLCAD [22]. The disordered region of the C-terminus in the crystal structure was further modeled using the Homology module that is part of the software. Mutated residues were positioned on the molecule as described to assess their possible effect [23, 24].

A case was considered “symptomatic” if the subject was reported to show symptoms potentially attributable to VLCAD deficiency at the initial evaluation or later (as described under “Results”). Creatine kinase (CK) levels less than 250 µM were considered normal in the first 30 days of life; rhabdomyolysis was defined as CK ≥ 1000 µM at any age. Because jaundice is common in neonates, jaundice alone did not qualify a subject as “symptomatic”. NBS blood spot C14:1 was the only biochemical marker utilized to compare symptomatic versus asymptomatic cases, as ratios using other acylcarnitines do not appear more discriminatory than C14:1 alone [25].

3. Results

3.1 General characteristics

Eighty patients with a diagnosis of VLCAD deficiency were identified in the IBEM-IS. Of these, 67 were ascertained by NBS and therefore met the inclusion criteria for this study. Nine of the cases ascertained via newborn screening were excluded due to lack of follow up diagnostic and clinical information entered in the IBEM-IS. An additional six cases were excluded after the authors considered NBS, diagnostic and molecular information and agreed that the cases likely represented carrier individuals, all of whom were alive at entry into the study (see below). Thus, 52 patients remained in the study cohort after the above exclusions, including a patient that was diagnosed prenatally. Clinical and biochemical data for these 52 patients were analyzed.

Demographics are summarized in Table 1. In this cohort, 21/52 (42%) were female, and the majority of subjects (73%) were of Caucasian race. Three subjects were reported to have Hispanic ethnicity. Age range at entry into the study was 11 days to 11.4 years, and ages 1 to 18 years at the last visit entered in the IBEM-IS. This study includes a total of 378 person-years of follow-up including data abstracted from retrospective chart review, as well as 101 person-years of prospective follow-up data collected after study enrollment. The majority of cases were between 6 to 11 years of age (55.8%) at last visit. One individual with cardiomyopathy died at 11.5 months from acute respiratory failure in the setting of congestive heart failure.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the cohort.

| Characteristic | Female | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 21 (40.4%) | 31 (59.6%) | 52 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 17 | 21 | 38 (73.1%) |

| African American | 2 | 6 | 8 (15.4%) |

| Multi-racial | 0 | 1 | 1 (1.9%) |

| Unreported/Missing | 2 | 3 | 5 (9.6%) |

| Average Age (years) at Intake (Range) | 2.3 (0.03–8.5) | 2.9 (0.22–11.4) | 2.7 (0.03–11.4) |

| Distribution | |||

| 1 – 5 years | 20 | 26 | 46 (88.5%) |

| 6 – 11 years | 1 | 5 | 6 (11.5%) |

| 12–18 years | --- | --- | --- |

| Average Age (years) at Time of Study (Range) | 7.3 (3.7–12.4) | 7.3 (2.5–18.5) | 7.3 (2.5–18.5) |

| Distribution | |||

| 1 – 5 years | 6 | 14 | 20 (38.4%) |

| 6 – 11 years | 14 | 15 | 29 (55.8%) |

| 12–18 years | 1 | 2 | 3 (5.8%) |

| Average Years of Follow-up | 2.7 (0.0–7.1) | 2.1 (0.0–6.4) | 2.4 (0.0–7.1) |

3.2 Biochemical abnormalities and diagnostic methods

Newborn screening results

C14:0 and/or C14:1 acylcarnitine data for the first NBS sample were available in 42/52 (81%) of cases. The mean value on the first NBS for C14:0 acylcarnitine values was 2.49 µM (median 1.50 µM, range 0.82 µM −7.14 µM, standard deviation 1.91 µM, n=30) and the mean C14:1 was 2.63 µM (median 1.64 µM, range 0.65 µM −10.89 µM, standard deviation 1.93 µM, n=42). In order to determine if initial C14:1 is a potential predictor of disease severity, acylcarnitine concentrations from cases deemed to be “symptomatic” were compared to other cases without any reported symptoms as of December 2015. The mean C14:1 was 1.94 µM (median 1.30 µM, range 0.65 µM −5.79 µM, standard deviation 1.37 µM) in the group without symptoms and 3.70 µM (median 3.40 µM, range 1.20 µM −10.89 µM, standard deviation 2.26 µM) in the group with reported symptoms (p<0.002).

3.3 Confirmatory testing

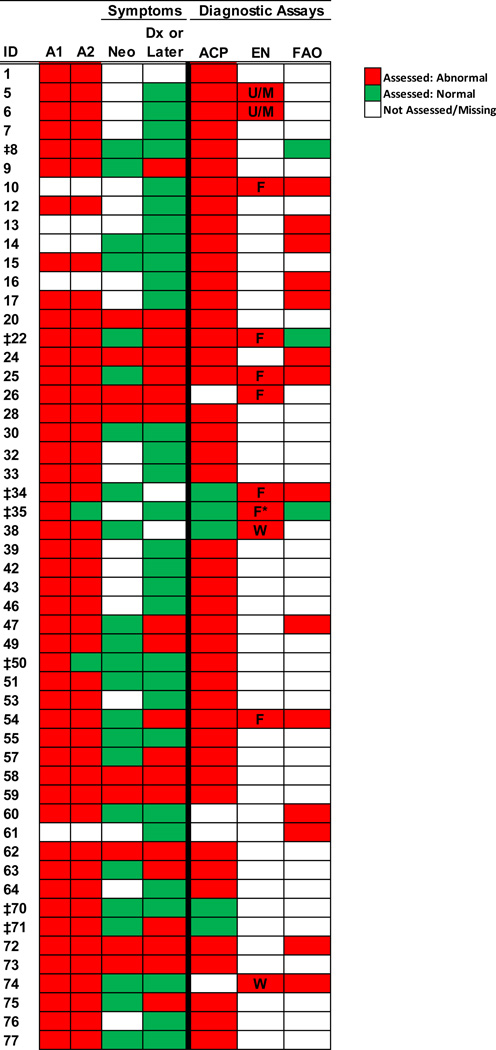

All patients entered in the database had confirmatory testing following the original abnormal NBS that was used to define the diagnosis as “definitive” or “possible.” The initial C14 and C14:1 acylcarnitine levels on the newborn screen and results of confirmatory testing were considered in our review of the cases. Among the remaining 52 cases, a majority of diagnoses were confirmed using a combination of two different assays (37/52), with the most common being a combination of plasma acylcarnitine profile and genotyping (26/52, Figure 1). Several individuals (7/52) had four or more different assays completed to confirm the diagnosis. Seven of 52 “definitive” cases had inconsistencies in diagnostic testing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Confirmation of Diagnosis.

Spectrum of assays and symptoms that were considered in confirming a VLCADD diagnosis in each subject.

Abbreviations: A1, ACADV Allele 1; A2, ACADV Allele 2; Neo, Symptoms during neonatal period; Dx, Diagnosis; ACP, Acyl carnitine profile; EN, VLCAD enzyme assay; FAO, fatty acid oxidation probe; U/M, unknown or missing information concerning source of tissue used; F, assay performed using fibroblasts; W, assay performed using leukocytes.

* Patient had normal results when assay was performed with leukocytes.

‡ Patients with inconsistent diagnostic results.

3.4 Genotype

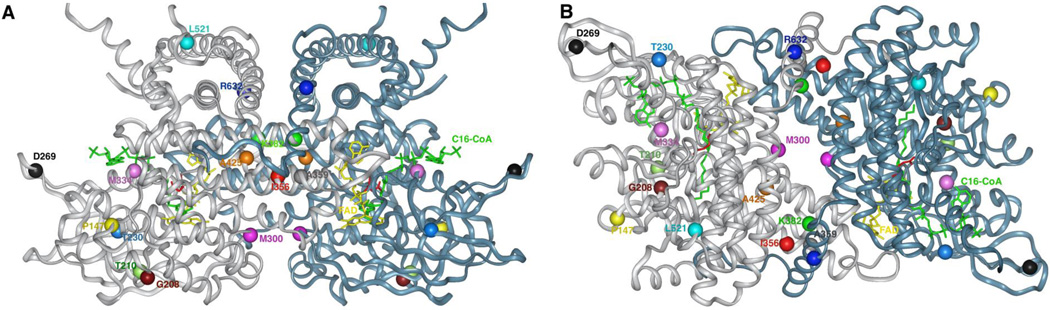

Molecular testing was reported in 46 of the 52 individuals included in the analysis. Two mutations were identified in 44/46 of these cases, while 2/46 had only one variant identified, for a total of 90 alleles. The genotype of one affected individual was assumed to be the same as a previously characterized deceased sibling, though this case was not included in genotype analysis. Most subjects (38/46, 83%) with available genotyping were compound heterozygotes. In total, there were 50 different alleles reported, 26 of which had not been previously reported. The majority of the reported changes represented missense variants. The most common mutation was a previously reported variant c.848T>C (p.V283A), present in 26/90 alleles. Other recurrent mutations were c.865G>A (p.G289R) in 5/90 and c.1844G>A (p.R615Q) in 3/90 alleles. Large deletions were not reported, but there were small insertions or deletions of 1 to 10 nucleotides reported in the cohort. Previously unreported alleles are represented in Table 2, and 17 point mutations were modeled onto the three dimensional structure of the VLCAD crystal structure (Figure 2). The predicted effect of the novel mutations is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Novel mutations identified in patient cohort.*

| Case | Symptomati c |

Allele 1 | Reference/prediction | Allele 2 | Reference/prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown |

(cDNA not available) p.T210P |

T210P affects the projection of a β-strand that is part of the core of the β-sheet domain and therefore affecting folding and β-sheet integrity. The same β-strand is directly involved in flavin moiety binding. The mutant protein expected to be either unable to fold or highly unstable. |

(c.194C>T;p.Pro65Leu) |

(Missplicing [31]) May affect interaction with other molecules; Pro65 not conserved across species |

| 8 | No | c.1146G>C; p.K382N | The K382 side chain amino group is within interaction distance (3.45 Å away) from the carboxylate of E432. More critically it is within interacting distance (4.15 Å) from the carboxylate of D466´, which is involved in FAD´ binding (the prime sign designate the second subunit). Loss of the above interactions destabilizes the tertiary and quaternary protein structure. Provided the monomer folds somewhat correctly, it will still lead to absence of functional protein. These three residues are invariant across >45 species. |

(1844G>A; p.R615Q) |

(Patient with lethal DCM [32]) Loss of proper interaction with E616, both residues are in the middle of an α-helix and seem structurally dispensable. Both residues are conserved in most species but substituted with Q and K, respectively, in some species. |

| 12 | No | p.A425T | A425 lies buried in the middle of the monomer as part of an α- helix and its methyl group is in a cavity <3 Å across, and so cannot tolerate any additional side chain atom. An A425T replacement will prevent proper tertiary folding. A425 is part of an 8 aa stretch that is invariant among all known species and a highly conserved core structure with minimal negligible variation in aa primary structure. |

(c.848T>C; p.V283A) | (Reduced protein stability) [23] |

| 15 | No | c.253dupG | Frameshift | (c.848T>C; p.V283A) | (Reduced protein stability [23]) |

| 20 | Yes | c294_297delGACA | Frameshift | (IVS11+1G>A) | (Missplicing)[1] |

| 22 | Yes | c1182(+3)G>T | Frameshift | (c.848T>C; p.V283A) | (Reduced protein stability[(3]) [23] |

| 26 | Yes | c.1617T>C | Synonymous, but splice site change per Mutation Taster | (Dup c.1707-1716) | (Frameshift) [24] |

| 32 | No | c.1076C>T; p.A359V | A359 residue is buried inside the monomer in a conserved pocket, ~1.5 α-helical turn away from the surface. Its methyl group lies opposite from and in between C443 and I446 side chains. While A359 and C443 are invariants across >45 species VLCADs, I446 is replaced with Val in some species, implying that protein plasticity may tolerate some changes. Val at the A359 position is predicted by in silico calculations that to be partially tolerated. |

(c.848T>C; p.V283A) | (Reduced protein stability [23] |

| 34 | No | c.1504C>G; p.L502V | L502 is in a disordered region in the crystal structure. It is expected, based on it being a conservative change that it will be structurally tolerated. It’s macromolecules could be affected. |

(1844G>A; p.R615QR615Q) |

(Patient with lethal DCM [32]) See Subject 8, Allele 2 above. |

| 38 | No |

(cDNA not available) p.R632C |

Highly conserved aa. At the surface of a C-terminus α-helix; may affect interaction with other neighboring macromolecules. |

c.1968A>C; p.X656C | Additional 32-aa peptide at the C-terminus, most likely destabilizing protein |

| 42 | No | c.865G>A; p.G289R | Part of a surface loop connecting two β -strands. May hamper proper folding. |

(cDNA not available) p.R531L |

R531 is an invariant residue across >45 species at the surface of the C-terminus where it hypothetically interacting with neighboring molecules. Its side chain is anchored by hydrophobic interaction with L484 and L535 side chains, that are invariants in >45 species. Such interaction implies that the guanidinium group may be critical for protein-protein. interaction. |

| 43 | No | c.865G>A; p.G289R | Part of a surface loop connecting two β-strands. May hamper proper folding. |

c.1501C>T | Synonymous; missplicing |

| 46 | No | c.1066A>G; p.I356V | I356 is in a buried hydrophobic pocket. Mutation would lead to less stable but likely partially functional mutant. |

(c.63-2A>C) | (Frameshift) [17] |

| 47 | Yes | c.622G>A; p.G208R | Despite being in a surface loop, an Arg residue would have its side chain oriented inwards into a spatial area that is occupied by other residues leading causing perturbation of the whole loop and hence destabilization of the protein |

c.689C>T; p.T230I | The T230 residue lies in an inner pocket at the structurally sensitive β-sheet domain. Modeling suggest the chance that the replacement is weakly tolerated is possible. |

| 57 | No | c.1532 G>C: ; R511P | R511 is at the end of the disordered region in the crystal structure connecting to an α-helix. A replacement with Pro provides unwanted rigidity to the disordered region but may be weakly tolerated. |

(c.848T>C; p.V283A) | (Reduced protein stability [23]) |

| 58 | Yes | c.1173_1174insT | Frameshift | c.1806_1807delCT | Frameshift |

| 62 |

Yes |

c.898A>G; p.M300V | M300 is located in a Hydrophobic pocket at a loop connecting two β-strands involved in FAD binding and at the monomer- monomer interface. It is predicted to affect FAD binding and reduce stability of dimer. |

c.1532G>A; p.R511Q | R511 is at the end of the disordered region in the crystal structure connecting to an α-helix with the side chain oriented outwards. A replacement with a Gln predicted to be tolerated. |

| 64 | No | c.388_390delGAG | Unstable protein | (c.829_831delGAG) | (Unstable protein) [17] |

| 71 | Yes | c.439C>T; P147S | P147 stabilizes a loop that is away from the active site, but still can impact protein structure integrity. |

c.956C>A; stop codon | Truncated VLCAD, no viable protein produced |

| 76 | No | c.1001T>G; p.M334R | M334 is replaced by Val in VLCAD of some species. Together with F330, an invariant in >45 species and across other ACAD family members, they form a critical binding site for the adenine moiety of the CoA substrate. It’s replacement hinder substrate binding but may be tolerated structurally. |

(c.1844G>A; p.R615Q) | (Patient with lethal DCM [32]) |

Novel mutations are in bold (previously published mutations are in italics).

Figure 2. Molecular model of VLCAD crystal structure and mutation positions.

Ribbon representation of VLCAD crystal structure, modeled using the published atomic coordinates of the VLCAD monomer, PDB code: 3B96. Modeled is the dimer form, lacking the C-termini disordered regions, and palmitoyl-CoA at the active sites. Depicting mutation positions are in CPK using the InsightII Modeling software (Dassault Systèmes, BIOVIA Corp – formerly Accelrys Technologies, San Diego, CA). Subunits A and B are colored light jade and gray, respectively. The novel mutations described in this manuscript are represented in different colored CPK and are described in the text and Table 2. The stick structures of FAD and palmitoyl-CoA are colored yellow and green, respectively. The stick structure of Glu462 (precursor numbering, Glu422 in mature numbering; GenBank accession number P49748.1), the catalytic base, is colored red. The view in panel A emphasizes the homology to other ACADs while in panel B shows the monomer interface. Note the mutations at the monomer interface, predicting a destabilizing effect on the dimer assembly.

3.5 Prenatal complications

Maternal and infant pre/post-natal complications are reported in Table 3. Maternal complications included increased blood pressure at the end of pregnancy (n=1), preeclampsia/toxemia (n=1) and preterm labor (n=1). Infants born to these three mothers had no complications or disabilities reported in the database. In this cohort, there were no cases of acute fatty liver of pregnancy, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, or low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, common complications in pregnant women carrying a fetus with a long chain FAOD [26]. Congenital anomalies included ventricular septal defects (n=3), patent foramen ovale/atrial septal defect (n=6), dilated cisterna magna (n=1) and anteriorly displaced anus (n=1).

Table 3.

Maternal, Pre and Postnatal Complications

| Complications, Abnormalities, and Symptoms | Number Affected |

|---|---|

| Pre-Evaluation | |

| Maternal Complications | |

| Elevated Blood Pressure | 1 |

| Preeclampsia/Toxemia | 1 |

| Preterm Labor | 1 |

| Fetal Complications | |

| Dilated Cisterna Magna | 1 |

| Anteriorly Displaced Anus | 1 |

| Neonatal Complications | |

| Hypoglycemia | 1 |

| Poor Feeding | 2 |

| Seizure-like Activity | 1 |

| Jaundice | 5 |

| Respiratory Distress | 2 |

| Initial Evaluation | |

| Symptoms | |

| Hypothermia | 4 |

| Respiratory Distress | 3 |

| Poor Feeding | 7 |

| Tachycardia | 1 |

| Jaundice | 5 |

| Lethargy | 2 |

| Macrocephaly, Dermatitis, Pneumonia, Emesis | 1 each |

| Lab Abnormalities | |

| Metabolic acidosis | 2 |

| Hypoglycemia | 6 |

| Elevated creatine kinase (CK) | 7 |

| Elevated liver function tests(LFTs) | 4 |

| Hypoproteinemia, hypocalcemia, hyperammonemia | 1 each |

| Cardiac Abnormalities | |

| VSD | 3 |

| PFO/ASD | 6 |

3.6 Neonatal complications and initial clinical evaluation

A neonatal complication was reported in 9/52 cases, but four infants with non-specific self-limited symptoms such as prematurity with respiratory distress or need for IV fluids were not included as “symptomatic”. Other cases (24, 26 and 59) had neonatal symptoms followed by more specific symptoms suggestive of VLCAD deficiency including hypoglycemia, and cardiomyopathy (case 58, Table 4). Two had poor feeding (cases 20 and 73) with later improvement in growth; one of these (73) had a history of elevated transaminases. One case (20) had neonatal hypoglycemia in addition to neonatal distress and poor feeding and went on to develop cardiomyopathy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of cases manifesting symptoms related to VLCAD deficiency

| Case | C14:1 NBS (µM) |

Neonatal Symptomsa | Symptoms/abnormal lab findings at or after initial evaluation |

Age at 1st CK elevation (yrs)b |

Peak CK level recorded (µM) |

Allele 1 | Allele 2 | Follow- up time (yrs) |

Age At last contact (yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 3.29 | No | Hypoglycemia Respiratory Distress |

-- | -- | G439D | M443R | 1.5 | 2.6 |

| 20 | 3.7 | Hypoglycemia Respiratory Distress Poor Feeding |

Hypothermia Poor Feeding Tachypnea Rhabdomyolysis Cardiomyopathy |

1 | 50,000 | c.294_297delGACA | c.IVS11+1G>A | 1.9 | 2.9 |

| 22 | 1.2 | No | Rhabdomyolysis | 2.6 | 2,700 | c.848T>C | c.1182(+3)G>T | 3.1 | 4.1 |

| 24 | 3.29 | Distress IV Fluid |

Hypoglycemia Hyperammonemia |

2.5 | 21,000 | c.1316G>A | c.1328T>G | 3 | 5.5 |

| 25 | 2.83 | No | Rhabdomyolysis | 1.3 | 40.500 | c.1182+1G>A | c.566T>C | 4.1 | 4.8 |

| 26 | -- | Prematurity Distress IV Fluid |

Hypoglycemia Lethargy Rhabdomyolysis |

6.1 | 142,520 | c.1617T>C | Dup1707-1716 | 3.1 | 8.9 |

| 28 | 2.6 | Weight loss at 5 days | Rhabdomyolysis | 1.9 | 1,000 | c.848T>C | c.848T>C | 0.0 | 1.9 |

| 47 | 3.6 | No | Rhabdomyolysis | 3.2 | 29,534 | c.622G>A | c.689C>T | 0.3 | 3.4 |

| 49 | 3.5 | No | Rhabdomyolysis | 3.4 | 49,324 | c.1375C>T | c.1375C>T | 0.5 | 3.9 |

| 54 | -- | No | Rhabdomyolysis | 12.7 | 63,000 | A770del | c.1613 G>C – MS | 6.3 | 16.7 |

| 57 | -- | No | -- | 4.3 | 367 | c.848T>C | c.1532 G>C | 4.1 | 4.9 |

| *58 | 4.89 | Distress | Hypoglycemia Hypotonia Apnea Hypothermia Arrhythmia Long QT Cardiomyopathy |

-- | -- | c.1173-1174insT | c.1806-7delCT | 0.0 | 4.5 |

| *59 | 10.89 | Distress IV Fluid |

Hypoglycemia Lethargy Acidosis Hypotonia Hypothermia |

0.7 | 805 | c.1173-1174insT | c.1806-7delCT | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| 62 | 4.38 | Distress IV Fluid Parenteral Nutrition |

Pneumonia Infections Rhabdomyolysis |

3.7 | 9,786 | c.839A>G | c.1532G>A | 4.6 | 6.1 |

| 63 | 1.36 | No | Rhabdomyolysis | 1.7 | 2,297 | C848T>C | 1505T>C | 5.1 | 4.6 |

| 71 | 2.76 | No | Elevated CK/LFT | 0.3 | 396 | c.439C>T | c.956C>A | 1.4 | 3.0 |

| 72 | 4.47 | Distress IV Fluid Prematurity |

Respiratory Distress Mild Cardiomegaly Elevated CK/LFT |

-- | -- | c.308A>G | c.1807-1808delCT | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 73 | 1.33 | Poor Feeder | Elevated LFT Poor Growth/Feeding |

-- | 175 | c.829-832delGAG | c.848T>C c.950T>C |

2.0 | 4.3 |

| 75 | 5.12 | No | Poor Feeding | -- | -- | c.605T>C | c.848T>C | 0.0 | 1.2 |

Neonatal symptoms are recorded in the IBEM-IS as part of the initial medical history intake and are defined to have occurred within the first 28 days of life.

For all subjects that developed rhabdomyol ysis, the age at first CK elevation was also the age at which the peak CK was recorded except for subject 54 whose peak CK was reported at 15.5 years of age.

The time period from birth to the initial metabolic evaluation following a positive NBS (“days to intervention”) averaged 7.1 days (median 6, range 0–26, including one prenatal diagnosis). Fifty one of 52 cases reported information regarding presence or absence of symptoms at the initial clinical evaluation. Of these, 32/51 had no symptoms. Symptoms at initial evaluation included jaundice (n=5), hypothermia (n=4), cardiomyopathy (n=1, case 20) and arrhythmias with prolonged QT and atrial flutter (n=1, case 58) (Table 3 and data not shown).

The presence or absence of abnormal labs at the initial evaluation was reported in 39/52 subjects. Abnormal laboratories, unrelated to diagnostic laboratories, were reported in 13/39 and included hypoglycemia (n=6), elevated CK (n=7), elevated liver function tests (n=4) and hyperammonemia (n=1).

3.7 Cardiac evaluations

An echocardiogram prior to the initial study visit was reported for 31/52 subjects. Structural findings are noted in Table 3. Incidental identification of PFO/ASD was found in 6 subjects. Subjects 9, 24 and 49 had a VSD identified; other symptoms in these subjects reported in Table 4 appear unrelated. Later cardiac evaluations were also reported in 31 subjects. Two subjects were reported to have aortic root dilatation, which resolved in one.

Abnormal echocardiograms were reported in several subjects before the initial visit or during interval visits. Subject 59 had “moderate right ventricular/pulmonary arterial hypertension” reported at initial intake at age 12 days. Follow-up echocardiogram demonstrated resolution by age 3 years. Two other subjects were reported as having cardiomyopathy. Subject 58 (sibling of 59) initially had normal cardiac structure and function at 3 days of age, but had intermittent atrial flutter with aberrant conduction reported at the initial evaluation. This child was diagnosed with prolonged QT interval (QTc 478msec) at 8 months of age, had findings of cardiomyopathy at age 11 months, and died of related complications two weeks later. Subject 20 had ""mild left ventricular hypertrophy, mostly of the septum” at six days of age. Repeat echocardiograms at ages two and five months were reported as “mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy”, unchanged from prior study. Between interval visits from ages one and two, the child was given a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 38%. The most recent echocardiogram at age three and a half years was reported as “normal biventricular size and function.” Among the cases with cardiomyopathy, the fatal case had novel frameshift mutations, and the other had a previously described severe mutation and a novel frameshift mutation (Table 2). Both cases also had neonatal complications including hypoglycemia and/or neonatal distress as well as later complications such as hypoglycemia, lethargy, poor feeding and/or elevated CK.

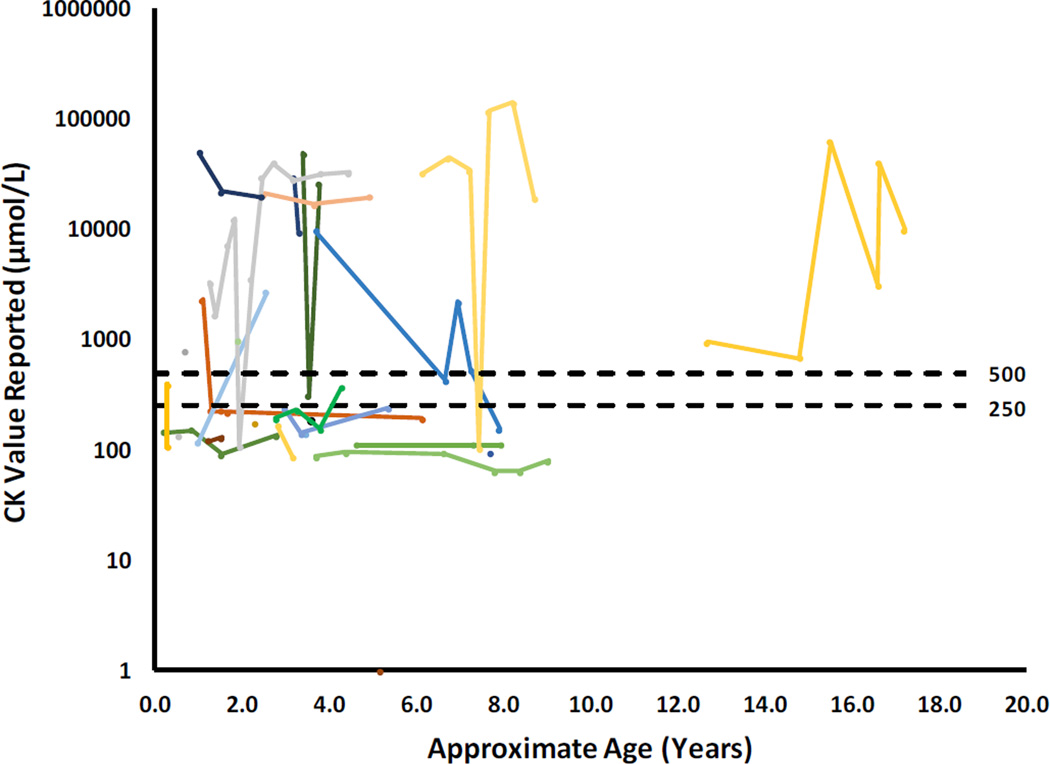

3.8 Rhabdomyolysis

CK levels, a marker for rhabdomyolysis, were available for 26 subjects, and the majority (18/26) had multiple values reported (Figure 3). Rhabdomyolysis is a frequently reported long-term complication of VLCAD deficiency. Fourteen subjects had at least one measurement of CK after the neonatal period that was 250 µM or higher, with the highest level of 142,520 µM. Of the 14 subjects with elevated CK, 11 developed rhabdomyolysis (CK ≥ 1000µM). The range of estimated ages at which elevated CK first appeared in the patient’s database records was 0.3–12.7 years (mean estimated age=3.2, median estimated age=2.6 years). These data could represent an under-ascertainment of the frequency of rhabdomyolysis as some potentially vulnerable cases may develop rhabdomyolysis later in life.

Figure 3. Creatine kinase levels reported in the cohort.

Creatine kinase levels reported at a visit, or during the interval between any two consecutive visits, is plotted above. Each subject is represented by a different color and values from a single subject are connected by a line. A single point with no line represents a patient with only one CK value recorded in the IBEM-IS. Multiple CK values were recorded for 18/26 subjects.

3.9 Treatment regimen

IBEM-IS captures dietary treatment, including cornstarch, medium chain triglyceride, and essential fatty acid supplementation. Information regarding fat restriction, intervals between feedings, carnitine supplementation, and protocols for managing intercurrent illness is also requested. Of the 52 subjects with a confirmed diagnosis of VLCAD deficiency, all but one (98%) had data available from at least one of these questions within 6 months of entry into the study. If the diet prescription was changed within 6 months of study entry, the most recent prescription is reported. At a mean age of 2.7 ± 2.5 years, 35 of 41 subjects (85%) were prescribed a fat-restricted diet, 24 of 32 (75%) were prescribed a source of medium chain triglycerides (MCT) either from a metabolic formula or oil/powder supplements (including 1 subject receiving triheptanoin (subject 20) [10], 9 of 40 (23%) received a supplemental source of essential fatty acids and 4 of 40 (10%) were prescribed cornstarch (Table 5). The subject who received triheptanoin had an increase in dose due to lower ejection fraction, without further deterioration in cardiac function reported at a subsequent visit. At the time of analysis, information regarding L-carnitine supplementation was available for only 21 subjects, and of these, all were prescribed carnitine. The maximum fasting time allowed when the individual was not ill ranged from 4 to 12 hours and varied based on the age of the subject (n=23). An emergency letter with or without a “sick day” plan for intercurrent illness was provided for 50 of 51 subjects (98%).

Table 5.

Treatment variables at initial visit for subjects with confirmed VLCAD deficiency after identification by newborn screening 1

| Recommended/Prescribed Treatment (n=number of responses)2 |

Yes, % (n) |

|---|---|

| Emergency protocol ± Sick day plan (n=51) | 98% (50) |

| Cornstarch (n=40) | 10% (4) |

| Essential Fatty Acids (n=40) | 23% (9) |

| Fat-Restricted Diet (n=41) | 85% (35) |

| MCT supplementation (n=32) | 75% (24) |

| L-Carnitine (n=21) | 100% (21) |

Data collected from subjects within 6 months of their initial study visit, ages 2.7 ± 2.5 years (Range 0.03 to 11.4 years).

For each variable, n is total number of subjects with available data to indicate if the treatment was prescribed or not; next column gives percent of these subjects who received the listed treatment.

4. Discussion

Expanded newborn screening has resulted in early diagnosis of individuals with VLCAD deficiency and changed the perceived spectrum of disease [27]. We have used the IBEM-IS longitudinal natural history study to provide a more complete picture of the early outcomes of these individuals. This analysis included 52 cases.

Not surprisingly, the first challenge in such a study is defining disease. It is likely that VLCADD encompasses a continuum of severity, including infants likely to have minimal risk for symptoms as well as those with life-threatening disease. Although the majority of patients ascertained through NBS now appear asymptomatic, we do not know if they will remain so throughout life. At 378 person-years of follow-up (range 0 to 18 years per case) in our data, cardiomyopathy presented in the first year in two cases. Elevated CK appeared in the first year of life in a few cases, but was more common in the toddler years in cases manifesting this finding. Other cases may still manifest rhabdomyolysis at a later age, however it appears that practitioners should be alert for this finding to appear at any age. Despite observations of maternal fatty liver of pregnancy in other long chain fatty acid disorders, no reports of this complication were noted in the cohort.

In most cases the state NBS laboratories did not report sufficient information to utilize the diagnostic algorithm previously described by the Region 4 Laboratory Performance Database (R4S)[28]. Confirmation of diagnosis by laboratory analysis appeared conflicting in some cases, making differentiating true from false positive NBS results challenging. Efforts to reach consensus on a bona fide diagnosis illustrate the quandaries in diagnosing VLCAD deficiency. Reaching a group consensus on a diagnosis required multiple rounds of discussion amongst the authors due to incomplete reporting in the database or inclusion of conflicting data. Almost all of the patients in this study had at least two different diagnostic tests, and some had up to five. The most common combination of confirmatory tests included an acylcarnitine profile and sequencing (16/52 cases). Seven questionable cases were ultimately accepted as being affected even though conflicting results were present in diagnostic testing (including two with only one DNA variant identified) because of at least one convincing laboratory abnormality. None of these seven was reported to be symptomatic and likely represent milder or later onset disease. Ongoing data collection will be needed to more clearly define genotype/phenotype correlations and better understand which patients are at risk of developing symptomatic disease.

Evaluation with publically available software to assess the significance of novel gene variants was helpful in many cases, but several required additional molecular modeling with the known crystal structure of VLCAD to provide insight on pathogenicity. All but one were predicted to be pathogenic based on our previous experience with this technique. One, L502V in patient 34 is predicted to affect the protein mildly. This patient had no neonatal symptoms, and follow up diagnostic acylcarnitine profile has been normal. However, fibroblast enzyme activity and acylcarnitine probe assay were both abnormal. These findings suggest that the patient is at risk for later onset symptoms. The most common mutation was a previously reported variant c.848T>C (p.V283A), present in 26/90 alleles in 21 cases. This mutation has previously been reported to be a mild variant, and in our series, 14/20 patients with this variant were asymptomatic. Of the 6 subjects that were symptomatic, 4/6 had elevated CK, 3 of who had levels greater than 1,000 at ages 1.1, 1.9, and 2.6 years of age, respectively (Table 4). The remaining 2 symptomatic patients exhibited poor feeding one of whom also had elevated liver function testing at 2.3 years of age. In total, these findings suggest that the presence of the p.V283A variant is likely to lead to symptoms only outside the newborn period. Complete inactivating/null alleles appear to predispose to the development of cardiomyopathy, as the two cases with cardiomyopathy had either two frameshift mutations (case 58) or a frameshift and a splicing mutation (case 20).

We reviewed records on six patients that ultimately appeared to be unaffected with VLCAD. Although specifically assessing such patients comprehensively is not a goal of IBEM-IS, based on available cases, it appears that the same combination of tests is effective in differentiating from affected individuals. Plasma acylcarnitine profiles and molecular testing were sufficient to diagnose approximately half of the cases. However, several patients had three or more assays, most frequently a functional assay such as a fatty acid oxidation probe or VLCAD enzyme assay. We suggest that an effective diagnostic approach for cases referred due to an abnormal NBS include plasma acylcarnitine profiles and molecular testing as a starting point. If two previously characterized mutations are identified, then no further confirmatory testing is necessary. If not, the, functional testing should be pursued as an adjunct. In our cohort, enzyme assay either on white blood cells or fibroblasts and fibroblast acylcarnitine profiling (often called a “fatty acid oxidation probe”) were nearly equivalent in identifying affected individuals. At least one clear false negative result for the fatty acid oxidations probe was reported in a patient shown to be affected by all other parameters including fibroblast enzyme assay (patient 22). However, one equivocal patient with an abnormal fibroblast enzyme assay and a normal fatty acid oxidation probe has other parameters suggestive of being a carrier (patient 35).

We note that the majority of patients with reported CK levels had elevations greater than 1000 µM reported at a relatively early age. Although rhabdomyolysis is a known complication of VLCAD deficiency, additional longitudinal studies are necessary to elucidate whether increased motor activity associated with early childhood can represent triggers. Additional findings include VSDs in 3/52 participants (5.8%), similar to the population incidence of 2–5% [29, 30] and mild aortic root dilatation noted in 1 patient. A larger cohort of patients with VLCAD deficiency is necessary to determine whether these observations represent an association with this disorder or are attributable to ascertainment bias. Finally, although maternal fatty liver has been reported in other FAOD, no reports were made in our cohort.

Recommendations for treatment of VLCAD deficiency often include nutritional interventions, fasting restriction, and/or supplementation with L-carnitine. Nutritional interventions varied, but the majority of the subjects in the cohort was prescribed a long chain fat-restricted diet with a source of MCT, and was provided with an emergency protocol to manage intercurrent illness. Cornstarch was rarely prescribed in this population, suggesting that restricting fasting time may have been sufficient to prevent hypoglycemia. For infants, the majority of MCT-based metabolic formulas are supplemented with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA). Other dietary sources of essential fatty acids (i.e. walnut oil) were not consistently prescribed. Diet data in the IBEM-IS show a wide variability in current diet therapy for patients with VLCAD deficiency. Further data collection will be necessary before firm conclusions can be drawn about the need and extent of required treatment based on the age of the patient and severity of VLCAD deficiency. Of note, while carnitine supplementation is often viewed as controversial in VLCAD deficiency, all patients with available data on this question were, in fact, receiving carnitine supplementation.

5. Limitations

It is important to note that our findings were derived from a convenience sample from a cohort participating in the IBEM-IS, and all subjects received care in the USA. The observations are cross-sectional with limited follow up in a young cohort, and analysis required resolution of queries regarding unclear or conflicting data and extensive curation. Despite these limitations, important observations could be made regarding diagnosis, laboratory abnormalities and clinical correlates for affected individuals with respect to our initial study questions.

6. Conclusion

Analysis of patients reported with VLCAD deficiency in the IBEM-IS demonstrates that most newborns identified by NBS remained asymptomatic, and that cardiomyopathy was uncommon. Moreover, maternal prenatal symptoms were not reported. Elevations in creatine kinase were a common finding, and usually first occurred during the toddler period (1–3 years of age). Diagnostic evaluations required several testing modalities, most commonly plasma acylcarnitine profiles and molecular testing. Functional testing, including fibroblast acylcarnitine profiling and white blood cell or fibroblast enzyme assay, is a useful diagnostic adjunct if uncharacterized mutations are identified. A majority of patients in our cohort received some sort of modified diet, including MCT oil, and all for whom data were reported, were on carnitine supplementation. Continued follow up of this cohort should provide further insights into long term outcome in patients with VLCAD deficiency identified by NBS.

Highlights.

We present outcomes data for a cohort of 52 individuals with VLCAD deficiency that are followed through the NIH funded Inborn Errors of Metabolism – Information System (IBEM-IS) database. This is a large group of affected individuals with longitudinal follow up and we believe the data presented will enhance our knowledge of the condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge review of cardiac phenotypes by Dr. Arnold Strauss and organizational support from Ms. Kaitlin Justice.

Funding support

NIH:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health under award number 5R01HD069039. JV was supported in part by R01DK78755.The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

NBSTRN:

This research was facilitated by the Newborn Screening Translational Research Network (“NBSTRN”), which is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (HHSN275201300011C).

HRSA

This research is facilitated by the Health Resource and Services Administration (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) Regional Genetic and Newborn Screening Services Collaboratives, Heritable Disorders Program through grants to: Region 2 - New York Mid-Atlantic Consortium for Genetic and Newborn Screening Services (NYMAC) (H46MC24094), Region 4 Midwest Genetics and Newborn Screening Collaborative (H46MC24092), Region 5 Heartland Genetic Services Collaborative (H46MC24089), and Region 6 - Mountain States Genetics Regional Collaborative (H46MC24095).

RedCap

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Michigan Public Health Institute (MPHI) (Harris et al, 2009).2REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources. http://www.projectredcap.org/cite.php

Abbreviations

- VLCAD

Very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- NBS

Newborn screening

- MCT

Medium chain triglycerides

- IBEM-IS

Inborn Errors of Metabolism Information System

- RUSP

Recommended Uniform Screening Panel

- CK

Creatine kinase

- HELLP syndrome

Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, or low platelets syndrome

Appendix

*For the Inborn Errors of Metabolism Collaborative: University of Colorado School of Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado (Janet Thomas, Melinda Dodge); Emory University Department of Human Genetics (Rani Singh, Sangeetha Lakshman, Katie Coakley, Adrya Stembridge); University of Iowa Health Care (Alvaro Serrano Russi, Emily Phillips) Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago (Barbara Burton, Clare Edano, Sheela Shrestha), University of Illinois (George Hoganson, Lauren Dwyer); Indiana University (Bryan Hainline, Susan Romie, Sarah Hainline); University of Louisville (Alexander Asamoah, Kara Goodin, Cecilia Rajakaruna, Kelly Jackson); Johns Hopkins (Ada Hamosh, Hilary Vernon, Nancy Smith); University of Michigan (Ayesha Ahmad, Sue Lipinski); Wayne State University Children’s Hospital of Michigan (Gerald Feldman); University of Minnesota (Susan Berry, Sara Elsbecker); Minnesota Department of Health (Kristi Bentler), University of Missouri (Esperanza Font-Montgomery, Dawn Peck); Duke University (Loren D.M. Pena, Dwight D. Koeberl, Yong-hui, Jiang, Priya S. Kishnani); University of Nebraska (William Rizzo, Machelle Dawson, Nancy Ambrose); Children’s Hospital at Montefiore (Paul Levy); New York Medical College (David Kronn); University of Rochester (Chin-to Fong, Kristin D’Aco, Theresa Hart); Women’ and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo (Richard Erbe, Melissa Samons); Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (Nancy Leslie, Racheal Powers); Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Dennis Bartholomew, Melanie Goff); Oregon Health and Science University (Sandy van Calcar, Joyanna Hansen); University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (Georgianne Arnold, Jerry Vockley); Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC (Cate Walsh-Vockley); Medical College of Wisconsin (William Rhead, David Dimmock, Paula Engelking, Cassie Bird, Ashley Swan); University of Wisconsin (Jessica Scott Schwoerer, Sonja Henry); West Virginia University (TaraChandra Narumanchi, Marybeth Hummel, Jennie Wilkins); Sanford Children’s Specialty Clinic (Laura Davis-Keppen, Quinn Stein, Rebecca Loman); Michigan Public Health Institute (Cynthia Cameron, Mathew J. Edick, Sally J. Hiner, Kaitlin Justice, Shaohui Zhai).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Strauss AW, Powell CK, Hale DE, Anderson MM, Ahuja A, Brackett JC, Sims HF. Molecular basis of human mitochondrial very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency causing cardiomyopathy and sudden death in childhood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:10496–10500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoyama T, Uchida Y, Kelley RI, Marble M, Hofman K, Tonsgard JH, Rhead WJ, Hashimoto T. A novel disease with deficiency of mitochondrial very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;191:1369–1372. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold GL, Van Hove J, Freedenberg D, Strauss A, Longo N, Burton B, Garganta C, Ficicioglu C, Cederbaum S, Harding C, Boles RG, Matern D, Chakraborty P, Feigenbaum A. A Delphi clinical practice protocol for the management of very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;96:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiekerkoetter U, Lindner M, Santer R, Grotzke M, Baumgartner MR, Boehles H, Das A, Haase C, Hennermann JB, Karall D, de Klerk H, Knerr I, Koch HG, Plecko B, Roschinger W, Schwab KO, Scheible D, Wijburg FA, Zschocke J, Mayatepek E, Wendel U. Management and outcome in 75 individuals with long-chain fatty acid oxidation defects: results from a workshop. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:488–497. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coughlin CR FC., 2nd1 Genotype-phenotype correlations: sudden death in an infant with very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(Suppl 33):S129–S131. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andresen BS1 OS, Poorthuis BJ, Scholte HR, Vianey-Saban C, Wanders R, Ijlst L, Morris A, Pourfarzam M, Bartlett K, Baumgartner ER, deKlerk JB, Schroeder LD, Corydon TJ, Lund H, Winter V, Bross P, Bolund L, Gregersen N. Clear correlation of genotype with disease phenotype in very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(62):479–494. doi: 10.1086/302261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang RN, Li YF, Qiu WJ, Ye J, Han LS, Zhang HW, Lin N, Gu XF. Clinical features and mutations in seven Chinese patients with very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. World J Pediatr. 2014;10:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s12519-014-0480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiekerkoetter U, Mayatepek E. Update on mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33:467–468. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa CG, Dorland L, de Almeida IT, Jakobs C, Duran M, Poll-The BT. The effect of fasting, long-chain triglyceride load and carnitine load on plasma long-chain acylcarnitine levels in mitochondrial very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:391–399. doi: 10.1023/a:1005354624735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vockley J, Marsden D, McCracken E, DeWard S, Barone A, Hsu K, Kakkis E. Long-term major clinical outcomes in patients with long chain fatty acid oxidation disorders before and after transition to triheptanoin treatment--A retrospective chart review. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djouadi F, Bastin J. PPARs as therapeutic targets for correction of inborn mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:217–225. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0844-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gobin-Limballe S, McAndrew RP, Djouadi F, Kim JJ, Bastin J. Compared effects of missense mutations in Very-Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase deficiency: Combined analysis by structural, functional and pharmacological approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastin J, Lopes-Costa A, Djouadi F. Exposure to resveratrol triggers pharmacological correction of fatty acid utilization in human fatty acid oxidation-deficient fibroblasts. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2048–2057. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roe CR, Brunengraber H. Anaplerotic treatment of long-chain fat oxidation disorders with triheptanoin: Review of 15 years. Experience Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newborn screening: toward a uniform screening panel and system. Genet Med. 2006;8(Suppl 1):1S–252S. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000223891.82390.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orngreen MC, Madsen KL, Preisler N, Andersen G, Vissing J, Laforet P. Bezafibrate in skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Neurology. 2014;82:607–613. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller MJ, Burrage LC, Gibson JB, Strenk ME, Lose EJ, Bick DP, Elsea SH, Sutton VR, Sun Q, Graham BH, Craigen WJ, Zhang VW, Wong LJ. Recurrent ACADVL molecular findings in individuals with a positive newborn screen for very long chain acyl-coA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency in the United States. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2015;116:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walter JH. Inborn errors of metabolism and pregnancy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2000;23:229–236. doi: 10.1023/a:1005679928521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoeman MN, Batey RG, Wilcken B. Recurrent acute fatty liver of pregnancy associated with a fatty-acid oxidation defect in the offspring. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:544–548. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90228-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Browning MF, Levy HL, Wilkins-Haug LE, Larson C, Shih VE. Fetal fatty acid oxidation defects and maternal liver disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:115–120. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000191297.47183.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims HF, Brackett JC, Powell CK, Treem WR, Hale DE, Bennett MJ, Gibson B, Shapiro S, Strauss AW. The molecular basis of pediatric long chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency associated with maternal acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:841–845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAndrew RP, Wang Y, Mohsen AW, He M, Vockley J, Kim JJ. Structural basis for substrate fatty acyl chain specificity: crystal structure of human very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9435–9443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709135200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goetzman ES, Wang Y, He M, Mohsen AW, Ninness BK, Vockley J. Expression and characterization of mutations in human very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase using a prokaryotic system. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;91:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiff M, Mohsen AW, Karunanidhi A, McCracken E, Yeasted R, Vockley J. Molecular and cellular pathology of very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marquardt G, Currier R, McHugh DM, Gavrilov D, Magera MJ, Matern D, Oglesbee D, Raymond K, Rinaldo P, Smith EH, Tortorelli S, Turgeon CT, Lorey F, Wilcken B, Wiley V, Greed LC, Lewis B, Boemer F, Schoos R, Marie S, Vincent MF, Sica YC, Domingos MT, Al-Thihli K, Sinclair G, Al-Dirbashi OY, Chakraborty P, Dymerski M, Porter C, Manning A, Seashore MR, Quesada J, Reuben A, Chrastina P, Hornik P, Atef Mandour I, Atty Sharaf SA, Bodamer O, Dy B, Torres J, Zori R, Cheillan D, Vianey-Saban C, Ludvigson D, Stembridge A, Bonham J, Downing M, Dotsikas Y, Loukas YL, Papakonstantinou V, Zacharioudakis GS, Barath A, Karg E, Franzson L, Jonsson JJ, Breen NN, Lesko BG, Berberich SL, Turner K, Ruoppolo M, Scolamiero E, Antonozzi I, Carducci C, Caruso U, Cassanello M, la Marca G, Pasquini E, Di Gangi IM, Giordano G, Camilot M, Teofoli F, Manos SM, Peterson CK, Mayfield Gibson SK, Sevier DW, Lee SY, Park HD, Khneisser I, Browning P, Gulamali-Majid F, Watson MS, Eaton RB, Sahai I, Ruiz C, Torres R, Seeterlin MA, Stanley EL, Hietala A, McCann M, Campbell C, Hopkins PV, de Sain-Van der Velden MG, Elvers B, Morrissey MA, Sunny S, Knoll D, Webster D, Frazier DM, McClure JD, Sesser DE, Willis SA, Rocha H, Vilarinho L, John C, Lim J, Caldwell SG, Tomashitis K, Castineiras Ramos DE, Cocho de Juan JA, Rueda Fernandez I, Yahyaoui Macias R, Egea-Mellado JM, Gonzalez-Gallego I, Delgado Pecellin C, Garcia-Valdecasas Bermejo MS, Chien YH, Hwu WL, Childs T, McKeever CD, Tanyalcin T, Abdulrahman M, Queijo C, Lemes A, Davis T, Hoffman W, Baker M, Hoffman GL. Enhanced interpretation of newborn screening results without analyte cutoff values. Genet Med. 2012;14:648–655. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez Junquera C, Balmaseda E, Gil E, Martinez A, Sorli M, Cuartero I, Merinero B, Ugarte M. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy and neonatal long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:103–106. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0696-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merritt JL, 2nd, Vedal S, Abdenur JE, Au SM, Barshop BA, Feuchtbaum L, Harding CO, Hermerath C, Lorey F, Sesser DE, Thompson JD, Yu A. Infants suspected to have very-long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency from newborn screening. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111:484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHugh D, Cameron CA, Abdenur JE, Abdulrahman M, Adair O, Al Nuaimi SA, Ahlman H, Allen JJ, Antonozzi I, Archer S, Au S, Auray-Blais C, Baker M, Bamforth F, Beckmann K, Pino GB, Berberich SL, Binard R, Boemer F, Bonham J, Breen NN, Bryant SC, Caggana M, Caldwell SG, Camilot M, Campbell C, Carducci C, Cariappa R, Carlisle C, Caruso U, Cassanello M, Castilla AM, Ramos DE, Chakraborty P, Chandrasekar R, Ramos AC, Cheillan D, Chien YH, Childs TA, Chrastina P, Sica YC, de Juan JA, Colandre ME, Espinoza VC, Corso G, Currier R, Cyr D, Czuczy N, D'Apolito O, Davis T, de Sain-Van der Velden MG, Delgado Pecellin C, Di Gangi IM, Di Stefano CM, Dotsikas Y, Downing M, Downs SM, Dy B, Dymerski M, Rueda I, Elvers B, Eaton R, Eckerd BM, El Mougy F, Eroh S, Espada M, Evans C, Fawbush S, Fijolek KF, Fisher L, Franzson L, Frazier DM, Garcia LR, Bermejo MS, Gavrilov D, Gerace R, Giordano G, Irazabal YG, Greed LC, Grier R, Grycki E, Gu X, Gulamali-Majid F, Hagar AF, Han L, Hannon WH, Haslip C, Hassan FA, He M, Hietala A, Himstedt L, Hoffman GL, Hoffman W, Hoggatt P, Hopkins PV, Hougaard DM, Hughes K, Hunt PR, Hwu WL, Hynes J, Ibarra-Gonzalez I, Ingham CA, Ivanova M, Jacox WB, John C, Johnson JP, Jonsson JJ, Karg E, Kasper D, Klopper B, Katakouzinos D, Khneisser I, Knoll D, Kobayashi H, Koneski R, Kozich V, Kouapei R, Kohlmueller D, Kremensky I, la Marca G, Lavochkin M, Lee SY, Lehotay DC, Lemes A, Lepage J, Lesko B, Lewis B, Lim C, Linard S, Lindner M, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Lorey F, Loukas YL, Luedtke J, Maffitt N, Magee JF, Manning A, Manos S, Marie S, Hadachi SM, Marquardt G, Martin SJ, Matern D, Mayfield Gibson SK, Mayne P, McCallister TD, McCann M, McClure J, McGill JJ, McKeever CD, McNeilly B, Morrissey MA, Moutsatsou P, Mulcahy EA, Nikoloudis D, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Oglesbee D, Oltarzewski M, Ombrone D, Ojodu J, Papakonstantinou V, Reoyo SP, Park HD, Pasquali M, Pasquini E, Patel P, Pass KA, Peterson C, Pettersen RD, Pitt JJ, Poh S, Pollak A, Porter C, Poston PA, Price RW, Queijo C, Quesada J, Randell E, Ranieri E, Raymond K, Reddic JE, Reuben A, Ricciardi C, Rinaldo P, Rivera JD, Roberts A, Rocha H, Roche G, Greenberg CR, Mellado JM, Juan-Fita MJ, Ruiz C, Ruoppolo M, Rutledge SL, Ryu E, Saban C, Sahai I, Garcia-Blanco MI, Santiago-Borrero P, Schenone A, Schoos R, Schweitzer B, Scott P, Seashore MR, Seeterlin MA, Sesser DE, Sevier DW, Shone SM, Sinclair G, Skrinska VA, Stanley EL, Strovel ET, Jones AL, Sunny S, Takats Z, Tanyalcin T, Teofoli F, Thompson JR, Tomashitis K, Domingos MT, Torres J, Torres R, Tortorelli S, Turi S, Turner K, Tzanakos N, Valiente AG, Vallance H, Vela-Amieva M, Vilarinho L, von Dobeln U, Vincent MF, Vorster BC, Watson MS, Webster D, Weiss S, Wilcken B, Wiley V, Williams SK, Willis SA, Woontner M, Wright K, Yahyaoui R, Yamaguchi S, Yssel M, Zakowicz WM. Clinical validation of cutoff target ranges in newborn screening of metabolic disorders by tandem mass spectrometry: a worldwide collaborative project. Genet Med. 2011;13:230–254. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31820d5e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sands AJ, Casey FA, Craig BG, Dornan JC, Rogers J, Mulholland HC. Incidence and risk factors for ventricular septal defect in "low risk" neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999;81:F61–F63. doi: 10.1136/fn.81.1.f61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roguin N, Du ZD, Barak M, Nasser N, Hershkowitz S, Milgram E. High prevalence of muscular ventricular septal defect in neonates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1545–1548. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00358-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe H, Orii KE, Fukao T, Song XQ, Aoyama T, L IJ, Ruiter J, Wanders RJ, Kondo N. Molecular basis of very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in three Israeli patients: identification of a complex mutant allele with P65L and K247Q mutations, the former being an exonic mutation causing exon 3 skipping. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:430–438. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200005)15:5<430::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathur A, Sims HF, Gopalakrishnan D, Gibson B, Rinaldo P, Vockley J, Hug G, Strauss AW. Molecular heterogeneity in very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency causing pediatric cardiomyopathy and sudden death. Circulation. 1999;99:1337–1343. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]