Abstract

Background

Some studies suggest that maternal influenza vaccination can improve birth outcomes. However, there are limited data from tropical settings, particularly Southeast Asia. We conducted an observational study in Laos to assess the effect of influenza vaccination in pregnant women on birth outcomes.

Methods

We consented and enrolled a cohort of pregnant woman who delivered babies at 3 hospitals during April 2014–February 2015. We collected demographic and clinical information on mother and child. Influenza vaccination status was ascertained by vaccine card. Primary outcomes were the proportion of live births born small for gestational age (SGA) or preterm and mean birth weight. Multivariate models controlled for differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated women and influenza virus circulation.

Results

We enrolled 5103 women (2172 [43%] were vaccinated). Among the 4854 who had a live birth, vaccinated women were statistically significantly less likely than unvaccinated women to have an infant born preterm during the period of high influenza virus circulation (risk ratio [RR] = 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI], .45–.70), and the effect remained after adjusting for covariates (adjusted RR, 0.69; 95% CI, .55–.87). There was no effect of vaccine on SGA or mean birth weight. The population-prevented fraction was 18.0%.

Conclusions

In this observational study, we found indirect evidence of influenza vaccine safety during pregnancy, and women who received vaccine had a reduced risk of delivering a preterm infant during times of high influenza virus circulation. Vaccination may prevent 1 in 5 preterm births that occur during periods of high influenza circulation.

Keywords: influenza vaccine, pregnant woman, preterm birth, small for gestational age, Laos

Influenza virus infections in pregnant women are associated with higher risks of severe outcomes, both during pandemics and seasonal influenza years [1–3]. Influenza vaccines are safe for pregnant women and their fetuses [4–7] and are effective in reducing the incidence of influenza among pregnant women [8, 9]. In addition, vaccination of pregnant women has reduced the risk of influenza in their infants during the first 6 months of life, a time of very high risk of severe influenza disease [8, 10]. In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts recommended that any country with an influenza immunization program should vaccinate pregnant women as a first priority [11]. National vaccination programs that target pregnant women have increased in some parts of the world [12]. In Southeast Asia, few countries recommend influenza vaccine in pregnant women [13].

In addition to the direct effect in preventing influenza illness, there is great interest in whether seasonal influenza vaccines could have an indirect effect on birth outcomes. Influenza virus infection during pregnancy is associated with an increased frequency of preterm birth and neonatal death [14]. Some observational studies have demonstrated a protective effect of influenza vaccination on adverse birth outcomes [15, 16], while others have shown no effect [17] and 2 randomized controlled trials showed different effects [8, 18]. Given the global mortality burden and cost associated with infants who have poor birth outcomes [19, 20], there are important implications of a protective vaccine effect. Moreover, the impact may vary by population or geographic-specific factor such as influenza seasonality and baseline rates of low-birth-weight or preterm births. Therefore, there is a need to evaluate possible associations in a variety of settings.

Since 2012, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) has offered influenza vaccine free of charge to high-risk persons, including pregnant women [21]. Laos is a country with a lower–middle income economy, with high rates of poor birth outcomes that have improved little in the last decade (S. Olsen, unpublished data). In 2014–2015, we conducted an observational study in pregnant women to assess the effect of influenza vaccine on birth outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

In this observational study, we enrolled a cohort of pregnant women at the time of delivery or miscarriage at 3 hospitals in Laos (the Mother and Child Health [MCH] and Setthathirath hospitals in Vientiane Capital Province and Luang Prabang Hospital in Luang Prabang Province). Laos is a Southeast Asian country with a population of 6.8 million and an annual birth cohort of 179 042 [22]. The objectives were to compare the proportion of infants born small for gestational age (SGA) or preterm and the mean birth weight among infants born to women who received and those who did not receive influenza vaccine from 20 March 2014 through 30 June 2014 and who delivered between April 2014 and February 2015.

Study Enrollment

From April 2014 through February 2015, we enrolled pregnant women who were aged ≥18 years, delivered at 1 of the 3 designated hospitals, were a resident of Vientiane Capital Province or Luang Prabang Province for at least the last 30 days, and had a singleton birth. Each woman provided written informed consent. A healthcare provider administered a brief questionnaire in the local language, usually within 12 hours of delivery. We collected the following information: demographic, pregnancy history, household income, underlying health conditions, respiratory illness during pregnancy, influenza vaccination status and date (self-report and documented), and birth outcomes. Medical records and vaccine registries are not regularly maintained at Laotian healthcare facilities; however, pregnant women are provided an antenatal care (ANC) booklet to record ANC visit information and are advised to bring this booklet to all ANC visits and their delivery. Information was obtained from the ANC booklets, interviews, and vaccination cards (see below).

Vaccine and Exposure Definition

The seasonal influenza vaccination campaign was conducted from 20 March 2014 through 30 June 2014 (see Supplementary Materials). The vaccine used was Afluria, the 2013–2014 Northern Hemisphere formulation of the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine [23], donated by bioCSL Biotherapies Inc. (Australia). At the time of vaccination, each pregnant woman received 1 dose and was given a vaccination card documenting the date of vaccination. The woman brought this card to the healthcare facility at the time of delivery. We defined vaccination as documented receipt of vaccine at least 14 days before delivery. We also calculated a variable for weeks of protection (see Supplementary Materials).

Primary Outcomes

Gestational age was calculated by last menstrual period captured at the first ANC visit (mean, week 14). SGA was calculated using the Kramer method [24], defined as a live birth with a birth weight less than the 10th percentile of birth weights of the same sex and same gestational age in weeks and expressed as a percentage of live births with gestational ages from 22 to 43 weeks. Preterm birth was defined as gestational age <37 weeks. Infant birth weight was measured at delivery.

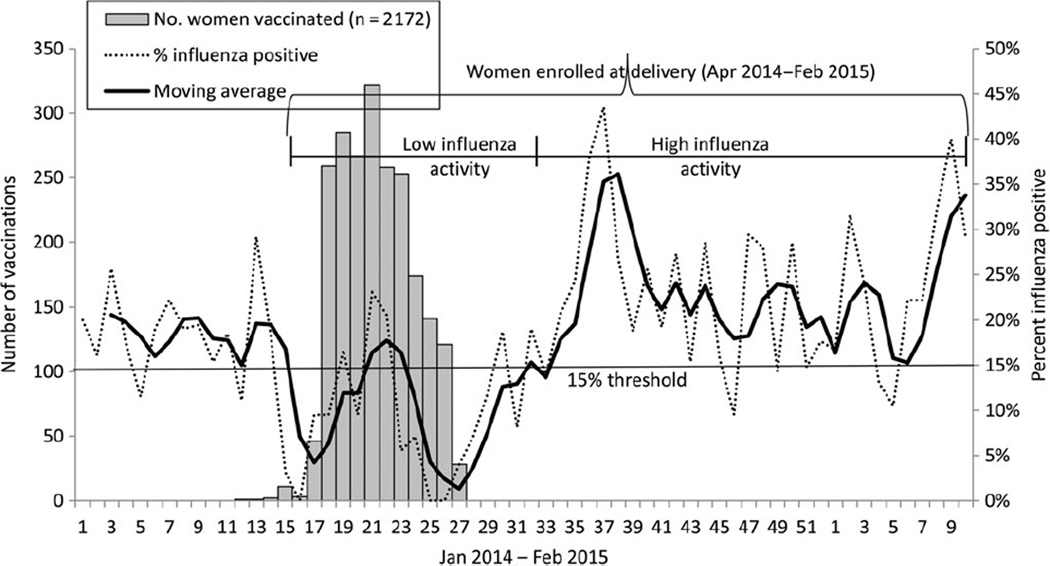

Influenza Activity

We used sentinel surveillance data for influenza-like illness to define periods of influenza activity [25]. We plotted weekly positivity and a 3-week moving average. We designated months as high (≥15% samples positive on real-time reserve transcription polymerase chain reaction assay) and low (<15%) influenza activity (Figure 1). Using this threshold, the continuous period of April 2014 to July 2014 experienced low influenza activity and August 2014 to February 2015 experienced high influenza activity. May 2014 (weeks 19–22) was a month with high activity (17%) but was kept in the “low influenza activity” period for the primary analysis. We used the period of low influenza activity as a control period during which we would expect little or no effect of vaccination.

Figure 1.

Influenza activity measured as percent positive for an influenza virus from sentinel surveillance for influenza-like illness [25], categorized by low and high activity, in Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and number of women vaccinated by week, 2014–2015.

Sample Size

Assuming a type I error of 5%, a type 2 error of 20%, and an influenza vaccine coverage in pregnant women of 50%, we estimated we would need to enroll 614 pregnant women to detect a difference of 9 percentage points in SGA (24% in unvaccinated vs 15% vaccinated, as estimated from Lee et al [19]) and 1100 pregnant women to detect a difference of 70 g in mean birth weight using a standard deviation of 390 (a difference estimated from unpublished 2013 data in vaccinated and unvaccinated women at MCH Hospital). In a post hoc sample size calculation for preterm birth, we estimated we would need 1937 pregnant women to detect a difference of 4 percentage points (12% in unvaccinated and 8% in vaccinated).

Statistical Analyses and Confounder Assessment

Data were double entered into Access (Microsoft Office 2010) and imported into SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 21) and Stata (StataCorp, release 12) for analysis. We compared characteristics of women vaccinated (with documentation) and unvaccinated using χ2 test or analysis of variance for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables; P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

We conducted bivariate analysis in order to compare birth outcomes by maternal vaccination status among all live births stratified by influenza activity (high/low). A priori we considered influenza activity and province as possible effect modifiers and used regression (log binomial for SGA and preterm birth [dichotomous] and linear for mean birth weight [continuous]) to assess for interaction between each variable and vaccination using the Wald χ2 test. For the multivariate analysis, we built log binomial models to evaluate the risk ratio (RR) of each dichotomous birth outcome (SGA status and preterm birth) and a multivariate linear regression model to predict the change in value of mean birth weight by vaccination status. We included covariates in each model that were statistically significant at P < .05 on bivariate analysis or otherwise considered in the existing literature as associated with both vaccination status and birth outcomes [15, 26, 27]. We report results for the full model. We also stratified by influenza activity (high/low) and ran the model after dropping this term from the model; results are also presented for each stratum. We then ran the model using weeks of protection instead of vaccinated (yes/no) but dropped the term “influenza activity” since it correlated with weeks of protection. We report adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and the difference of means. We calculated the population prevented fraction of preterm birth as shown elsewhere [15, 28]. In a separate analysis, to control for residual confounding, we calculated propensity scores to adjust each pregnant woman’s probability of being vaccinated; we also ran sensitivity analyses (see Supplementary Materials).

Ethics

The Ministry of Health (MoH) Institutional Ethics Review Board was not involved since the Department of Hygiene and Health Promotion, Maternal and Child Health Center, MoH, deemed that this activity did not meet study criteria. At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the protocol was reviewed and determined to be public health evaluation, not research. Reporting conforms to the STROBE (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) statement [29].

RESULTS

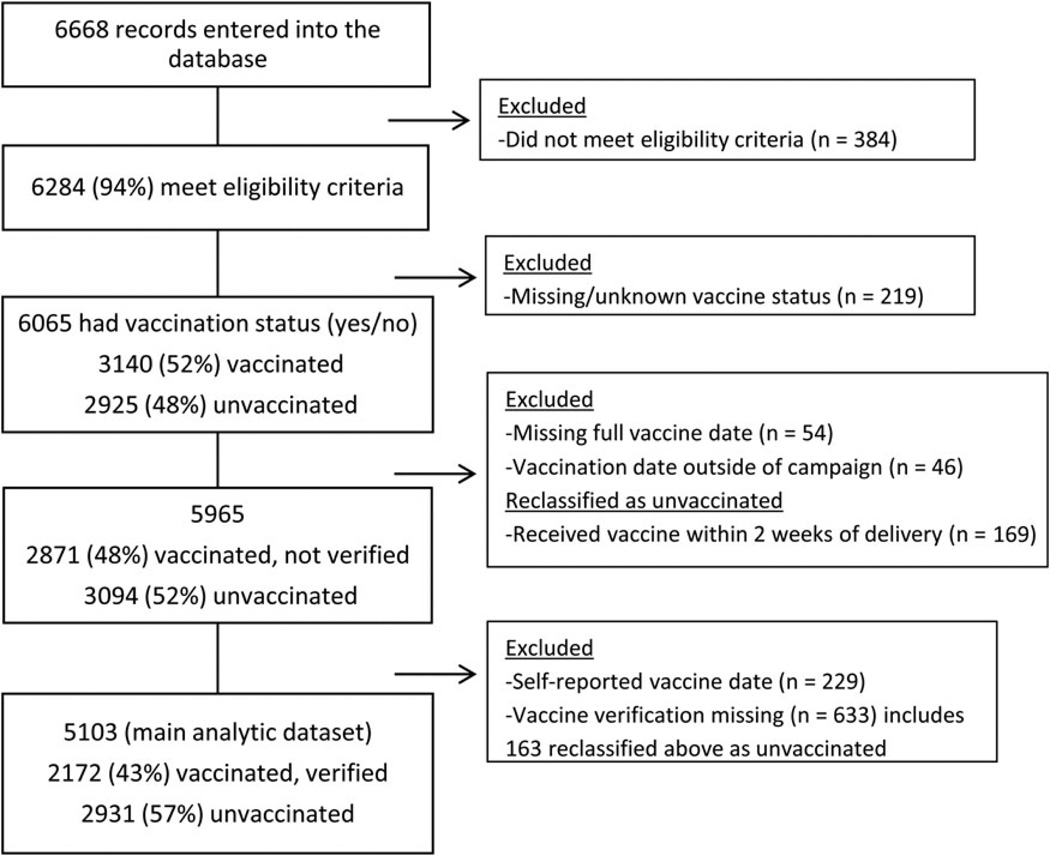

Between 4 April 2014 and 27 February 2015, we enrolled 6668 women; 5103 were in the final dataset (Figure 2; Supplementary Materials). Of the 5103 women with verified vaccination status, 2172 (43%) were vaccinated, and coverage did not differ between mothers with infants born in periods with high vs low influenza activity (P = .63). Fifty-four percent received vaccine during the second trimester (Table 1). Of the 5103 women, 4854 (95.1%) had a live birth, 222 (4.4%) had fetal mortality (31 miscarriages <22 weeks, 46 still births ≥22 weeks, 145 unknown gestational age), 14 were born live but died within 7 days after birth (11 died the same day as birth; 3 died 1, 4, and 6 days after birth), and 13 were missing an outcome. Twenty-six (11%) of the 236 deaths occurred among babies whose mothers were vaccinated.

Figure 2.

Enrollment of pregnant women in Lao, People’s Democratic Republic, 4 April 2014–27 February 2015.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Women Delivering by Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Status, Lao, People’s Democratic Republic, 2014–2015

| Characteristic of Mother | Total (n = 5103), N (%) | Vaccinated (n = 2172), N (%) | Unvaccinated (n = 2931), N (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y (range) | 27 (17–49) | 27 (17–44) | 27 (17–49) | .60 |

| Hospital | <.001 | |||

| Mother and Child Health | 2218 (43.5) | 934 (43.0) | 1283 (43.8) | |

| Setthathirath | 1354 (26.5) | 523 (24.1) | 831 (28.4) | |

| Luang Prabang | 1531 (30.0) | 715 (32.9) | 816 (27.8) | |

| Ethnic groupa | <.001 | |||

| Lao Loum | 4433 (86.9) | 1979 (91.2) | 2454 (83.8) | |

| Hmong | 419 (8.2) | 129 (5.9) | 290 (9.9) | |

| Khamu | 237 (4.6) | 57 (2.6) | 180 (6.1) | |

| Other | 10 (0.2) | 6 (0.3) | 4 (0.1) | |

| Educationa | <.001 | |||

| None | 151 (3.0) | 22 (1.0) | 129 (4.4) | |

| Some primary | 276 (5.4) | 70 (3.2) | 206 (7.1) | |

| Completed primary | 618 (12.2) | 223 (10.3) | 395 (13.5) | |

| Some secondary | 1197 (23.5) | 489 (22.6) | 708 (24.3) | |

| Completed secondary | 2844 (55.9) | 1363 (62.9) | 1481 (50.7) | |

| Mean no. people in household (range) | 5.0 (1–20) | 4.9 (1–20) | 5.1 (1–20) | .02 |

| Mean no. people aged <15 y (range) | 1.7 (0–10) | 1.6 (0–9) | 1.8 (0–10) | <.001 |

| Distance from home to hospital | <.001 | |||

| 0–5 km | 2036 (40.0) | 969 (44.7) | 1067 (36.5) | |

| >5–10 km | 1416 (27.8) | 601 (27.7) | 815 (27.9) | |

| >10 km | 1637 (32.2) | 599 (27.6) | 1038 (35.5) | |

| Household income, (500 000 Kip = USD$62) | ||||

| >5 000 000 | 603 (11.8) | 298 (13.7) | 305 (10.4) | <.001 |

| 1 000 001–5 000 000 | 3236 (63.5) | 1427 (65.7) | 1809 (61.8) | |

| 500 001–1 000 000 | 797 (15.6) | 256 (11.8) | 541 (18.5) | |

| ≤500 000 M | 464 (9.1) | 191 (8.8) | 273 (9.3) | |

| No. of antenatal visits | <.001 | |||

| <4 visits | 1034 (20.3) | 116 (5.3) | 918 (31.3) | |

| ≥4 visits | 4066 (79.7) | 2054 (94.7) | 2012 (68.7) | |

| Pregnancy history | ||||

| Mean gravida/pregnancies (range) | 2.3 (1–16) | 2.2 (1–11) | 2.4 (1–16) | <.001 |

| Mean parity/live deliveries (range) | 0.9 (0–12) | 0.7 (0–5) | 1.0 (0–12) | <.001 |

| Mean no. abortion (range) | 0.5 (0–8) | 0.5 (0–6) | 0.5 (0–8) | .03 |

| Mean no. live birth (range) | 0.8 (0–12) | 0.7 (0–5) | 0.9 (0–12) | <.001 |

| Mean no. stillbirths (range) | 1.3 (0–5) | 1.0 (1–1) | 1.4 (0–5) | .25 |

| Chronic disease | 96 (1.9) | 39 (1.8) | 57 (1.9) | .70 |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 18 (0.4) | 3 (0.1) | 15 (0.5) | .03 |

| Smoker in the household | 1690 (33.1) | 699 (32.2) | 991 (33.8) | .22 |

| Respiratory illness during pregnancy | 417 (8.2) | 180 (8.3) | 237 (8.1) | .80 |

| Hospitalized during pregnancy | 42 (0.8) | 13 (0.6) | 29 (1.0) | .13 |

| Trimester of vaccination | 1842 | |||

| First (<14 wk) | 449 (24) | |||

| Second (≥14 and <27 wk) | 989 (54) | |||

| Third (≥27 wk) | 404 (22) | |||

| Unknown (missing last menstrual period) | 330 |

Also significant at P < .0001 for Lao Loum vs other and completed secondary school vs other.

Vaccinated and unvaccinated women were similar with respect to mean age (27 vs 27 years), mean number of people in the household (4.9 vs 5.1), frequency of having chronic disease (1.8% vs 1.9%), the presence of a smoker in the household (32.2% vs 33.8%), having a respiratory illness (8.3% vs 8.1%), or being hospitalized (0.6% vs 1.0%) during pregnancy (Table 1). Vaccinated women were statistically significantly more likely than unvaccinated women to belong to the Lao Loum ethnic group (91.2% vs 83.9%; P < .001), to have completed secondary school (62.9% vs 50.7%; P < .001), and to have fewer persons aged <15 years in the household (mean 1.6 vs 1.8; P < .001). Vaccinated women were also more likely to live closer to a hospital, report a higher monthly household income, and have had 4 or more ANC visits (94.7% vs 68.7%; P < .001).

To assess the effect of vaccination on birth outcomes, we limited the analytic dataset to live births (n = 4854). The proportion classified as SGA was 4.2%, and this did not differ for infants born to vaccination and unvaccinated mothers (4.7% vs 3.8%; P = .16; Table 2). There was no difference in the crude or adjusted risk of SGA among vaccinated women, and the same was true when the data were stratified by high or low influenza activity (Table 2). The proportion of live births classified as preterm was 10.2%, and this differed significantly by vaccinated and unvaccinated mothers (7.5% vs 12.8%; P < .001). The crude (RR = 0.58; 95% CI, .48–.71) and (aRR = 0.70; 95% CI, .57–.87) to vaccinated women was significantly protective against having an infant born preterm. When we stratified by influenza activity, the protective effect of the vaccine remained only among infants born during the period of high influenza activity. Among live births, the mean birth weight was 3070 g, and this did not differ between infants born to vaccinated and unvaccinated mothers (3082 g vs 3060 g; P = .09). The difference in the mean birth weight after adjusting for covariates was 2 g greater among infants born to vaccinated women, and the means for infants born to vaccinated and unvaccinated had overlapping CIs; there was no difference when the data were stratified by influenza activity. Using weeks of protection, the only statistically significant effect was for preterm birth; for every week of protection there was a 4% reduced risk of preterm birth (RR = 0.96; 95% CI, .95–.98).

Table 2.

Analysis of Birth Outcomes by Maternal Vaccination Status and Influenza Activity Among Women Who Had Live Births (n = 4854)

| Outcome | Total N (%) | Vaccinated N (%) | Unvaccinated N (%) |

P Value for Crude Analysis |

Crude Risk to Vaccinated (95% CI) |

Adjusteda Risk Ratio to Vaccinated (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion small for gestational age | 156/3699 (4.2) | 85/1811 (4.7) | 71/1888 (3.8) | .16 | 1.25 (.92–1.70) | 1.25 (.91–1.72) |

| High influenza activity | 129/3129 (4.1) | 71/1532 (4.6) | 58/1597 (3.6) | .16 | 1.28 (.91–1.79) | 1.22 (.86–1.74) |

| Low influenza activity | 27/570 (4.7) | 14/279 (5.0) | 13/291 (4.5) | .76 | 1.12 (.54–2.35) | 1.50 (.71–3.17) |

| Proportion preterm | 378/3709 (10.2) | 136b/1819 (7.5) | 242/1890 (12.8) | <.001 | 0.58 (.48–.71) | 0.70 (.57–.87) |

| High influenza activity | 316/3137 (10.1) | 111/1538 (7.2) | 205/1599 (12.8) | <.001 | 0.56 (.45–.70) | 0.69 (.55–.87) |

| Low influenza activity | 62/572 (10.8) | 25/281 (8.9) | 37/291 (12.7) | .14 | 0.70 (.43–1.13) | 0.83 (.50–1.37) |

| Difference in means (vaccinated–unvaccinated) |

Difference in marginal means (vaccinated–unvaccinated) |

|||||

| Mean birth weight, g (standard deviation) | 3070 g (451) | 3082 g (423) | 3060 g (471) | .09 | +22 g | +1.6 gc |

| High influenza activity (n = 4079) | 3077 g (453) | 3092 g (425) | 3065 g (473) | .06 | +27 g | +9 gd |

| Low influenza activity (n = 767) | 3035 g (439) | 3030 g (412) | 3039 g (458) | .78 | −9 g | −39 ge |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; g, grams.

Adjusted for mother’s age, parity, province, ethnicity, education, income, number of antenatal visits, number of household members, and distance to hospital. The model for the first row for each outcome includes births occurring at any point (April 2014– February 2015) with a term included for influenza activity (high/low). The model for the row “high influenza activity” only includes births occurring in months August 2014–February 2015 and the model for the row “low influenza period” only includes births occurring in the months April–July 2014. For these models, the term for influenza activity was not included in the model.

The proportion of infants born preterm by trimester of maternal vaccination: 42/441 (9.5%) first trimester, 83/976 (8.5%) second trimester, 11/402 (2.7%) third trimester (P < .001).

Mean and 95% Wald CI for vaccinated (3019 g, 2987–3051) and unvaccinated (3018 g, 2990–3051).

Mean and 95% Wald CI for vaccinated (3043 g, 3010–3076) and unvaccinated (3034 g, 3006–3062).

Mean and 95% Wald CI for vaccinated (2957 g, 2888–3027) and unvaccinated (2996 g, 2940–3051).

The numbers were too small to analyze the effect of trimester of maternal vaccination on birth outcomes. In our prespecified subgroup analysis, we found no significant interaction between vaccination and influenza activity for SGA (P = .77), preterm birth (P = .36), or birth weight (P = .31). We found no significant interaction between vaccination and province on SGA (P = .22) but we did find it for preterm birth (P = .01) and birth weight (P = .03). We estimated that the fraction of preterm births prevented in the population by vaccination was 8.1% in the period of low and 18.0% in the high influenza virus circulation period.

A few other variables had an independent effect on the primary outcomes (Supplementary Table 1A–C). Using propensity scores, the primary results for preterm birth were similar (see Supplementary Table 1B). In the sensitivity analysis we found no substantial differences (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

DISCUSSION

In this cohort study in Laos, we found that pregnant women who received an influenza vaccine were statistically significantly less likely to have an infant born preterm (ie, at <37 weeks) compared with unvaccinated pregnant women. The effect, about a 30% reduced risk, was observed for the entire period, but when we stratified by influenza activity, the effect remained only for infants born during times of high influenza virus circulation. This translated to about 20% population prevented fraction in the period of high influenza activity, or roughly 1 in 5 preterm births being prevented by influenza vaccination. When weeks of protection was used as the main exposure, there was a 4% reduction in preterm births for every week of protection. We found no difference of effect in the 2 other birth outcomes. These findings provide additional indirect evidence of the safety of influenza vaccines during pregnancy (ie, no heightened risk of adverse birth outcomes related to vaccinees) but they also suggest that influenza vaccine may have a protective effect on preterm birth.

There is biologic plausibility that influenza virus infection could result in preterm birth—infections lead to inflammation, a recognized mechanism for preterm birth [30, 31]—so it is also plausible that influenza vaccination could prevent preterm birth. In a recent review of studies that looked at the association between influenza vaccination and preterm birth, Fell and colleagues concluded that overall there appeared to be a small reduction or no difference in risk [17]. However, only 6 studies looked at trivalent vaccines (13 included monovalent pandemic vaccines) and only 2 [15, 18] of the 6 took influenza virus activity into account in the analysis. Our study, which had simultaneous monitoring of influenza virus circulation, a large sample size, and verification of vaccination status, is an important addition to the literature.

The lack of an effect of vaccine on SGA was not entirely surprising for 2 reasons. First, we calculated an unexpectedly low frequency (4%) of SGA in our population and may not have had the power to detect a difference. Second, a single insult during pregnancy, such as influenza virus infection, may not be enough to have a sustained impact on the intrauterine environment and result in an infant born SGA. Moreover, the baseline birth weight in our population was substantially higher than in the other populations where an impact on SGA and birth weight was documented [18].

In many countries in Southeast Asia influenza viruses circulate year-round, so it was perhaps not surprising that in our study the effect of vaccination on preterm birth in the low season was also protective, but the difference was not statistically significant in part possibly because of fewer births. In fact, a higher magnitude (and significance) of association between maternal influenza vaccination and preterm birth during the period of high influenza activity supports the internal validity of our findings. There is growing recognition that year-round vaccination strategies may prevent more disease, particularly among pregnant women and their infants, and our data suggest that such a strategy may be beneficial in tropical settings [32].

Many factors affect birth outcomes, so it was not surprising to find that parity, education, ANC, and income had some independent effects. Women in this cohort had good access to ANC (80% had the WHO recommended more than 4 visits), and many women were vaccinated at an antenatal visit as this was an outreach method used during the vaccination campaign. Therefore, ANC and vaccination status may have some overlapping or synergistic effects. The observed differences in effects by province may be explained by the use of a Ministry of Health Maternal Neonatal Child Health package designed to increase access to and use of healthcare among rural and underserved communities in the Northern provinces, including Luang Prabang, through the provision of free care and treatment, transportation, and food.

This evaluation has several limitations inherent to observational studies, namely, that there might be unmeasured differences between people who do and do not get vaccinated [33]. Although we measured and controlled for differences in health-seeking behaviors and socioeconomic status, there may be residual confounding. Furthermore, we measured nonspecific effects of vaccination and, although we were able to look at the effect by the amount of influenza virus circulating, we do not know which pregnant women got influenza disease nor do we have an estimate of vaccine effectiveness in this setting; in the United States the vaccine effectiveness of the 2013–2014 Northern Hemisphere vaccine was about 60% [34]. Finally, consistent with a seasonal vaccine campaign, the majority of women in our study were vaccinated just before the period of high influenza circulation, resulting in the majority delivering during this period and leaving only a small sample to evaluate vaccine effects in the low season.

Influenza vaccine is safe and effective in pregnant women and should be given as recommended [11]. Although many factors contribute to improved outcomes for infants, our findings provide evidence that influenza vaccine may reduce some fraction of preterm births, especially in settings where the burden of preterm births is high, and further evidence that maternal immunization with influenza vaccine is safe. Preterm birth is a leading cause of infant mortality [20], and preventing even a small fraction would be an important achievement. Many low- and middle-income countries have high rates of poor birth outcomes; in tropical regions, these countries may experience year-round influenza virus circulation. Adding influenza vaccine to the current package of antenatal services may be beneficial in countries such as Laos.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kim Lindblade and Prabda Prapasiri for assistance in training; Waraporn Sakornjun and Nartlada Chantharojwong for setting up the Access database; Ivo Foppa, Wanitchaya Kittikraisak, and Sofia Arriola for consultation on the analytic approach; and Pui Ketmayoon for assistance with the influenza surveillance data.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Influenza Division, through a contract with the Expanded Program on Immunizations, Ministry of Public Health, Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), and by the government of Lao PDR.

Footnotes

Presented in part: International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, GA, 24–26 August 2015. Poster 86.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://cid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC or the Lao PDR Ministry of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, et al. H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the USA. Lancet. 2009;374:451–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuzil KM, Reed GW, Mitchel EF, Simonsen L, Griffin MR. Impact of influenza on acute cardiopulmonary hospitalizations in pregnant women. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:1094–1102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Bresee JS. Pandemic influenza and pregnant women. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:95–100. doi: 10.3201/eid1401.070667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratton KN, Wardle MT, Orenstein WA, Omer SB. Maternal influenza immunization and birth outcomes of stillbirth and spontaneous abortion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:e11–e19. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller-Stanislawski B, Englund JA, Kang G, et al. Safety of immunization during pregnancy: a review of the evidence of selected inactivated and live attenuated vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32:7057–7064. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mak TK, Mangtani P, Leese J, Watson JM, Pfeifer D. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: current evidence and selected national policies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:44–52. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moro PL, Broder K, Zheteyeva Y, et al. Adverse events in pregnant women following administration of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, 1990–2009. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:146.e1–146.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhi SA, Cutland CL, Kuwanda L, et al. Influenza vaccination of pregnant women and protection of their infants. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:918–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson MG, Li DK, Shifflett P, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal trivalent influenza vaccine for preventing influenza virus illness among pregnant women: a population-based case-control study during the 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 influenza seasons. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:449–457. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaman K, Roy E, Arifeen SE, et al. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1555–1564. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, April 2012—conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:201–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ropero-Alvarez AM, Kurtis HJ, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Ruiz-Matus C, Andrus JK. Expansion of seasonal influenza vaccination in the Americas. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:361. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta V, Dawood FS, Muangchana C, et al. Influenza vaccination guidelines and vaccine sales in Southeast Asia: 2008–2011. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meijer WJ, van Noortwijk AG, Bruinse HW, Wensing AM. Influenza virus infection in pregnancy: a review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:797–819. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omer SB, Goodman D, Steinhoff MC, et al. Maternal influenza immunization and reduced likelihood of prematurity and small for gestational age births: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legge A, Dodds L, MacDonald NE, Scott J, McNeil S. Rates and determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnancy and association with neonatal outcomes. CMAJ. 2014;186:E157–E164. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fell DB, Platt RW, Lanes A, et al. Fetal death and preterm birth associated with maternal influenza vaccination: systematic review. BJOG. 2015;122:17–26. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinhoff MC, Omer SB, Roy E, et al. Neonatal outcomes after influenza immunization during pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2012;184:645–653. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee AC, Katz J, Blencowe H, et al. National and regional estimates of term and preterm babies born small for gestational age in 138 low-income and middle-income countries in 2010. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e26–e36. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10(suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phengxay M, Mirza SA, Reyburn R, et al. Introducing seasonal influenza vaccine in low-income countries: an adverse events following immunization survey in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2015;9:94–98. doi: 10.1111/irv.12299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.GAVI. The Lao People’s Democratic Republic. [Accessed 10 March 2015]; Available at: http://www.gavi.org/country/lao-pdr/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO. Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2013–14 Northern Hemisphere influenza season. [Accessed 28 March 2016]; Available at: http://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/2013_14_north/en/

- 24.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E35. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khamphaphongphane B, Ketmayoon P, Lewis HC, et al. Epidemiological and virological characteristics of seasonal and pandemic influenza in Lao PDR, 2008–2010. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:304–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baum U, Leino T, Gissler M, Kilpi T, Jokinen J. Perinatal survival and health after maternal influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination: a cohort study of pregnancies stratified by trimester of vaccination. Vaccine. 2015;33:4850–4857. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordin JD, Kharbanda EO, Vazquez Benitez G, et al. Maternal influenza vaccine and risks for preterm or small for gestational age birth. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1051.e2–1057.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiologic research: principles and quantitative methods. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 29.STROBE Statement. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. [Accessed 4 November 2015]; Available at: http://www.strobe-statement.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bastek JA, Gomez LM, Elovitz MA. The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:385–406. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romero R, Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Kusanovic JP, Friel L, Hassan S. The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:21–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambach P, Alvarez AM, Hirve S, et al. Considerations of strategies to provide influenza vaccine year round. Vaccine. 2015;33:6493–6498. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson JC, Jackson ML, Weiss NS, Jackson LA. New strategies are needed to improve the accuracy of influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates among seniors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:687–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flannery B, Thaker SN, Clippard J, et al. Interim estimates of 2013–14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:137–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.