Abstract

Metabolic oxidative stress has been implicated as a cause of osteocyte apoptosis, an essential step in triggering bone remodeling. However, little is known about the oxidative behavior of osteocytes in vivo. We assessed the redox status and distribution of total and active mitochondria in osteocytes of mouse metatarsal cortical bone in situ. Multiphoton microscopy (MPM) was used to measure fluorescence of reduced pyridine nucleotides (NADH) under normoxic conditions and acutely following extreme (postmortem) hypoxic stress. Under non-hypoxic conditions, osteocytes exhibited no detectable fluorescence, indicating rapid NADH re-oxidation. With hypoxia, NADH levels peaked and returned to near baseline levels over 3 hours. Cells near the periosteal surface reached maximum NADH levels twice as rapidly as osteocytes near the mid-cortex, due to the time required to initiate NADH accumulation; once started, NADH accumulation followed a similar exponential relationship at all sites. Osteocytes near periosteal and endosteal bone surfaces also had higher mitochondrial content than those in mid-cortex based on immunohistochemical staining for mitochondrial ATPase-5A (Complex V ATPase). The content of active mitochondria, assessed in situ using the potentiometric dye TMRM, was also high in osteocytes near periosteum, but low in osteocytes near endocortical surfaces, similar to levels in mid-cortex. These results demonstrate that cortical osteocytes maintain normal oxidative status utilizing mainly aerobic (mitochondrial) pathways but respond to hypoxic stress differently depending on their location in the cortex, a difference linked to mitochondrial content. An apparently high proportion of poorly functional mitochondria in osteocytes near endocortical surfaces, where increased apoptosis mainly occurs in response to bone remodeling stimuli, further suggest that regional differences in oxidative function may in part determine osteocyte susceptibility to undergo apoptosis in response to stimuli that trigger bone remodeling.

Keywords: Osteocytes, Oxidative metabolism, mitochondrial function, In situ imaging, multiphoton microscopy, cortical bone

1. Introduction

Stress on osteocytes leading to apoptotic cell death appear to play essential roles in triggering bone remodeling due to diverse stimuli that include microdamage, disuse, ovariectomy and aging [1–7]. Yet the specific nature of those stresses, and the ways in which osteocytes respond to them, are frequently unclear. In estrogen loss, aging and disuse, for example, osteocyte apoptosis occurs where there is no obvious local trauma such as bone microcracks, and even at bone microdamage sites, apoptosis is more widespread than can be accounted for by direct physical injury to osteocytes by microcracks.

Local metabolic stress has been posited to be a major contributor to osteocytes apoptosis in all of these instances. Verborgt et al [8] suggested that microdamage in fatigued bone might disrupt canalicular integrity, altering fluid flow and reducing metabolite access to osteocyte, leading to apoptosis; further, Tami et al [9] confirmed experimentally that microcracks impaired fluid and solute transport through the lacunar-canalicular system (LCS). They also observed that this poorly perfused region around microcracks coincided with the area where osteocyte apoptosis occurs and where many osteocytes showed acutely elevated levels of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α). Thus, impaired metabolite transport and consequent oxidative and metabolic stress appear to be major triggers of osteocyte apoptosis in microdamage regions. In disuse, lack of mechanical loading broadly impairs fluid and solute transport in the LCS [10], causing potentially similar oxidative and metabolic stresses on osteocytes [11].

Estrogen loss also causes osteocyte apoptosis [4–6], but does not alter the LCS and fluid transport in cortical bone [12]. However, Emerton et al [4] in our laboratory demonstrated that the osteocytes that underwent apoptosis after estrogen loss were the oldest osteocytes in cortical bone, that they resided in regions of tissue with poor baseline perfusion and that they exhibited elevated levels of pre-existing oxidative damage. As a result, the authors speculated that estrogen was protective against oxidative stress and apoptosis in osteocytes. Indeed, estrogen administration has been shown to exert anti-oxidant effects and to protect cells after acute brain and heart injury [13, 14]. Recent data also indicate that estrogen directly affects mitochondrial function, principally by regulating the biogenesis of electron transfer complex components [15].

Finally, oxidative stress has been proposed as a pivotal mechanism contributing to age-related bone loss [7, 16] as it has been implicated in the tissue degeneration associated with aging [17]. Thus the potential for impaired oxidative metabolism and mitochondrial stress appears to be a common denominator in all the physiological challenges that cause osteocyte apoptosis.

The oxidative metabolism of osteocytes in bone is poorly understood. Electron microscopy studies by Belanger [18] and others [19, 20] established that osteocytes have numerous mitochondria, but their mitochondrial content is reduced as they age. Recently, Guo et al [21] demonstrated by immunohistochemistry that osteocytes located deep in cortical bone express high levels of glycolytic enzymes, along with the ORP150 protein which suppresses hypoxia-induced apoptotic cell death, while osteocytes near bone surfaces did not. These data suggest that the metabolic profiles of osteocytes are complex and may be functionally specialized by location within bone. However, the oxidative metabolism of osteocytes in bone remains poorly studied.

Direct assessment of cellular oxidative metabolism was pioneered in the 1950s by Chance and others, through monitoring the intrinsic fluorescence of the reduced form of the pyridine nucleotide NADH; the oxidized form (NAD+) is not fluorescent [22, 23]. Subsequent advances in fluorescence microscopy have greatly improved the ability to monitor NADH levels in real time, both in cell culture and in vivo and ex-vivo at precise locations. Recently, multiphoton fluorescence microscopy (MPM) has seen wide use for monitoring oxidative metabolism via NADH fluorescence in brain [24, 25], muscle [26] and other soft tissues [27, 28]. MPM has proven particularly advantageous as the low energy photons in this approach allow prolonged observations without phototoxicity to living cells and tissues, while the longer wavelength light used for MPM excitation reduces tissue scattering and allow deeper tissue penetration into tissues. However, the efficacy of such approaches to study metabolism in osteocytes in situ in fully mineralized bone is not known.

The objective of the current study was to examine the metabolic state of osteocytes in bone in situ under normal conditions and in response to stress. To do so, we developed a novel approach to monitor real time osteocyte cellular NADH levels in situ in mouse long bone cortices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 - Visualization of mouse osteocytes in vivo by multiphoton microscopy (MPM)

All experiments were performed on adult female C57BI/6 mice (15–17 week old, Jackson Lab, Bar Harbor, ME) and were IACUC approved. In vivo observations were made on cortical bone osteocytes in the mid-diaphysis of the 2nd and 3rd metatarsal bones (MT-2 and MT-3). This anatomic site is advantageous for direct visualization of cortical osteocytes in living animals. The dorsal surfaces of MT-2 and MT-3 are effectively subcutaneous, allowing easy access for study with minimal surgery. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane inhalation (0.5–2%). The skin and extensor aponeurosis on the dorsal MT surfaces were incised longitudinally with a scalpel to expose the bone; the periosteum was left intact. The surgical approach does not alter the major metatarsal blood supply, which comes from the arterial arcade located on the volar surface; the dorsalis pedis artery, which is located along the dorsal surface of MT-2, primarily supplies the digits rather than metatarsals and can be retracted from the surgical field. For observations, the mouse was placed on a warming blanket and the foot was positioned in a petri dish and submerged in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution at 37°C. The foot was stabilized with a custom-made holder to prevent movements caused by the animal’s heartbeat and respiration. The entire apparatus was set onto the stage of a multiphoton imaging system (Ultima, Bruker Instruments, Inc, Middleton WI) for observation. The microscope light source was a Ti-sapphire laser tunable from 680 to 1080 nm and focused on the tissue by a 40X magnification water immersion objective (Olympus LUMPLFLN 40XW, NA = 0.8; working distance = 3.3 mm).

2.2 - NADH fluorescence detection

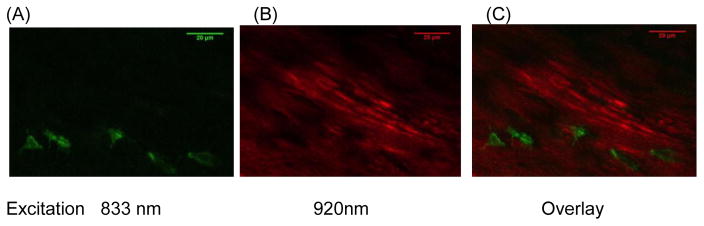

Fluorescence excitation and emission wavelengths were established to permit the specific measurement of NADH independent of other fluorescent materials in cells and extracellular matrix. The cellular NADH fluorescence spectrum is clearly separate from other cellular fluorophores (e.g. flavins) [27]. However, the emission spectra of NADH, partially overlaps with that of collagen [29, 30]. To resolve the fluorescence of osteocyte NADH from that of the collagen-rich matrix, we carried out an excitation spectrum study following the methods described by Hillman et al [31]. In brief, we used MPM to scan a mouse metatarsal diaphysis containing both cells and matrix. Scans were carried out 30 minutes after animal death a period sufficient to induce NADH accumulation in cells, based on pilot studies. Excitation wavelengths were varied between 700 nm and 960 nm in 20 nm increments; emitted fluorescent signals were collected from each scan with a 460±25 nm band-pass filter. The emission light intensities were measured using ImageJ. We found that dual photon excitation at 833 nm elicited NADH fluorescence in osteocytes but not the surrounding matrix (Fig 1a). In contrast, excitation at 920 nm resulted in matrix fluorescence but not in cells or lacunar spaces, which remained dark (Fig 1b). These wavelengths were used for subsequent experiments to image NADH and bone matrix respectively.

Figure 1.

Multiphoton microscopy (MPM)-based visualization of fluorescence from osteocyte NADH and bone matrix in mouse metatarsal cortex at 30 μm below the periosteal surface. (A) shows NADH fluorescence (excitation: 833 nm) in osteocytes at 30 min after of the onset of hypoxia; (B) shows collagen fluorescence (excitation: 920 nm) and (C) shows the overlay image of A and B. Emitted signals were captured with a 460 nm filter. (40X Objective, Field width = 125 μm).

2.3 - Assessment of oxidative state: NADH measurement in osteocytes in situ

The responsiveness of osteocyte oxidative metabolism was calibrated by measuring NADH fluorescence following hypoxia induction [23]. Mice (n=4) were anesthetized using isoflurane and prepared for imaging as described above. Baseline in vivo osteocyte images were acquired over 2–4 hours under anesthesia, after which mice were euthanized by anesthesia overdose to induce hypoxia. This approach is a a well-validated, widely used model to induce and study complete hypoxia in tissues and organs [32]. During the development of hypoxia from the postmortem tissue ischemia, osteocyte images were acquired over observation periods of 3 hours.

NADH fluorescence images were acquired beginning at the periosteal surface and sequentially captured to depths (z-axis) of 90 μm below the periosteal surface, which is approximately half the cortical width for adult mouse metatarsals. Fluorescence signals became degraded beyond that depth. For each study, a time (t-) series of a z series images (1μm steps) were captured every 5 minutes. At the end of each NADH imaging session for a bone, the complete z-stack was imaged again at 920nm (the collagen excitation wavelength) to visualize the bone matrix. With the 40X magnification objective used and the 90μm depth limit for the z-axis, we typically visualized 20–30 osteocytes per bone in a single experiment. NADH fluorescence signal intensity was measured in arbitrary intensity units as follows: Integrated fluorescence intensity was determined from 3D reconstructions of individual osteocytes at each time point using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Changes in integrated NADH fluorescence intensity were normalized to peak fluorescence in each osteocyte in order to facilitate inter-animal comparisons.

2.4 - Measurement of osteocyte active mitochondrial content using a potentiometric dye

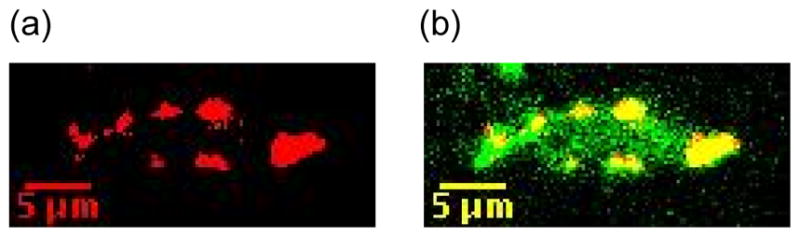

Imaging studies were also performed using the membrane potential sensitive dye Tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM, Invitrogen, T-668) to assess the content of active mitochondria in live osteocytes. TMRM is a cell-permeant, cationic, red-orange fluorescent dye that is readily sequestered by actively respiring mitochondria [33]. Mice (N=6) were injected with TMRM (100 μg in 100 μl of DMSO, IV injection) to visualize mitochondria. Mice were also injected with the vital dye Calcein AM (Invitrogen, 100 μg in 100 μl PBS, IP) which is taken up by live cells and retained throughout the entire cytoplasm; the calcein AM staining was used to measure total osteocyte cell volumes. Metatarsal cortical osteocytes were then imaged by MPM. Calcein AM and TMRM were excited simultaneously at 965 nm, and fluorescence emissions were collected at 500–530 nm for Calcein AM and 565–615 nm for TMRM, respectively. Calcein AM and TMRM staining were initially visualized in vivo, in osteocytes beneath the periosteal surface as described above for NADH. Subsequently, fresh tissue sections were used in order to analyze osteocytes throughout the entire cortical width. Mice were injected with dyes, then sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the metatarsals were excised, sectioned in HBBS transversely at the mid-diaphysis, and immediately imaged by MPM. Both methods yielded the same results in regions of tissue where they could be directly compared (data not shown). Measurements of active osteocyte mitochondrial content were performed using NIH ImageJ. Briefly, TMRM images were subjected to local adaptive thresholding and the resulting binary images were used to measure Active Mitochondrial Content (Vactive mito), which is a direct indicator of mitochondrial activity [34]. Calcein AM images were used to define referent osteocyte cell volumes (Vosteocyte) and % Active Mitochondrial Content per osteocyte was calculated as Vactive mito / Vosteocyte. (Fig 2)

Figure 2.

MPM-based images of a single osteocyte in vivo stained with TMRM (red) for active mitochondria and Calcein AM (green, B) to stain cytoplasm. (A) shows the isolated TMRM staining and (B) shows the overlay image of the same field with both TMRM and Calcein AM staining.

2.5 - Osteocyte mitochondrial content: Immunohistochemical staining for mitochondrial ATPase-5A

ATP synthase-5A (ATPase-5A) is the mitochondrial ATP synthase of Complex V in the electron transport chain, and so the amount of ATPase-5A within a cell can be used as an indicator of total mitochondrial content. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for ATPase-5A, was performed on diaphyseal cross-sections to assess the overall mitochondrial content of osteocytes throughout the entire cortical width, as described above for TMRM staining. Metatarsals were isolated after euthanasia (n= 6 mice), fixed in neutral buffered formalin and processed for IHC staining. Diaphyses were decalcified and 10 μm thick cross-sections were immunostained following the bone IHC protocol detailed by us in Kennedy et al [1]. ATPase-5A was probed using a monoclonal anti-ATPase-5A antibody (Abcam, 15H4C4) and detected using an AlexaFluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, A11029). Sections were imaged using Structured Illumination Microscopy (Zeiss Elyra SIM), a super-resolution microscopy approach which resolves at ~85 nm for the wavelength used here [35], allowing detection of mitochondria. To quantify mitochondrial content, the area of mitochondrial staining per cell area was calculated using ImageJ. This procedure was performed for the entire periosteal to endocortical width.

2.6 - Statistical analyses

Data are reported as mean ± s.d. Analyses were perofmred using SPSS (IBM, v.20). ANCOVA was used to compare the time courses of NADH fluorescence by osteocytes at different locations within the cortex. The distributions of total mitochondrial content of osteocytes (by ATPase-5A) and active mitochondrial content (by TMRM) across the entire cortical width were curve-fit using regression analyses.

3. Results

3.1 - NADH fluorescence in osteocytes under normoxic and hypoxic conditions

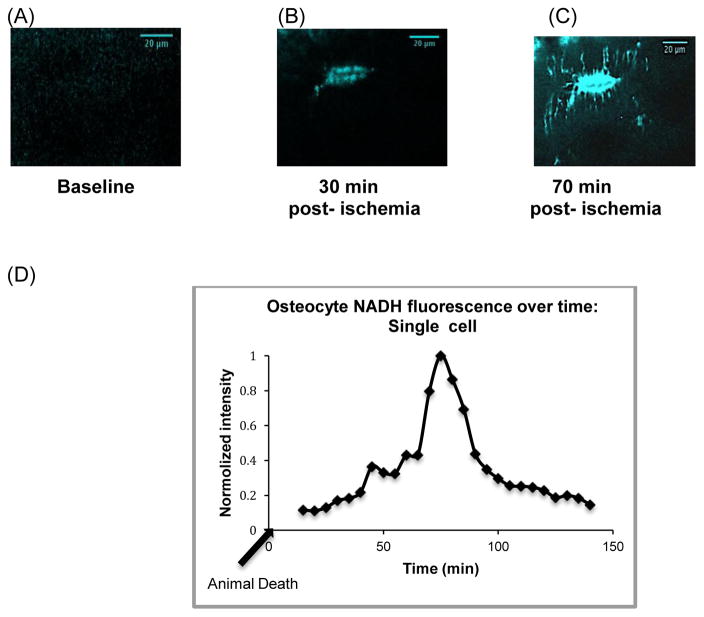

NADH fluorescence was not observed in osteocytes in vivo under baseline conditions, indicating that any NADH produced by metabolic pathways was rapidly re-oxidized to NAD+ before it could accumulate (Fig 3a). Furthermore, NADH remained below detectable levels even after anesthesia periods of 2 hours (data not shown), suggesting that neither the anesthesia nor the acute immobilization of the limbs during the observation period adversely affected osteocyte oxidative metabolism. Following euthanasia, NADH fluorescence was seen within 30 minutes within cell bodies (Fig 3b), then spread toward osteocyte processes (Fig 3c). Fluorescence eventually declined in all cells; a typical time course of fluorescence intensity monitored in a single osteocyte following hypoxia is shown in Figure 3d.

Figure 3.

Changes in metatarsal cortical osteocyte NADH fluorescence in situ due to hypoxia. (A) NADH fluorescence was not detectable in osteocytes at baseline under anesthesia. (B, C) show an osteocyte (30 μm deep from periosteum) at 30 and 70 minutes post-mortem, with NADH fluorescence increased dramatically, beginning in cell bodies and then extending to cell processes. (D) shows a representative plot of NADH fluorescence changes with time post-mortem (arrow indicates time of animal death) in a single osteocyte located 20 μm below the periosteal surface. NADH fluorescence peak at approximately 75 min after hypoxia induction then decline progressivly to baseline level after prolonged hypoxia.

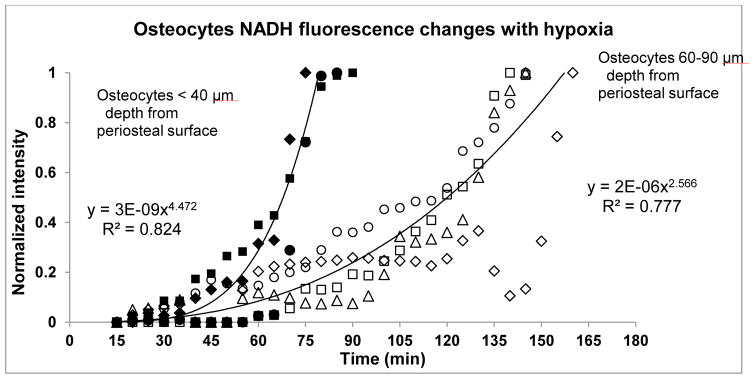

NADH fluorescence following hypoxia induction differed markedly depending upon osteocyte location within the cortex as shown in Figure 4. Osteocytes located within 40 μm of the periosteal surface reached peak fluorescence at 75 ± 6 minutes after the onset of the hypoxic stress. However, osteocytes located deeper in the cortex (60–90 μm from the periosteal surface, or approximately 50% of the MT cortical width) took almost twice as long to reach peak fluorescence levels (150 ± 11 minutes). In both cases, fluorescence accumulation followed a strong exponential relationship. The difference in time-to-peak fluorescence was highly significant (p<0.001) but the rates of fluorescence increase were similar (p>0.5), indicating that the difference in time to peak NADH levels was due primarily to the time required to initiate NADH accumulation.

Figure 4.

Time course of hypoxia-induced changes in NADH fluorescence of osteocytes located at different depths within the diaphyseal cortex. Data show the fraction of maximum fluorescence as a function of time in superficially located osteocytes (<40 μm beneath the periosteal surface, closed symbols) and deeper osteocytes (60 – 90 μm beneath the periosteal surface, open symbols). Each symbol represents a mean value of relative fluorescence obtained from 5 non-adjacemt osteocytes in a single microscopic field; different symbols (squares, circles etc) indicate osteocytes from four different animals. Best-fit lines from the equations shown on the figure were determined from serial measurements of osteocytes each animal. There was a marked difference between superficial and deep osteocytes in the time to maximum NADH fluorescence osteocytes (75 ± 6 vs. 150 ± 11 minutes, respectively, p<0.001) but no difference in exponents reflecting the rates of increase (p>0.5).

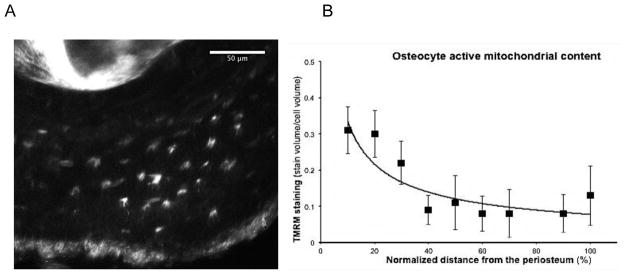

3.2 - Osteocyte Mitochondrial Activity: TMRM studies

Imaging of excised metatarsal cross-sections showed that the content of active mitochondrial (TMRM signal) was greatest in osteocytes near the periosteum then decreased by approximately 2/3 at mid-cortex and remained low up to the endocortical surface (Fig 5). Decrease in osteocyte mitochondrial activity through the cortical width followed an inverse power-type relationship (Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

Active mitochondrial content of osteocytes assessed in situ after TMRM staining (a) TMRM fluorescence in cross-section of mouse metatarsal mid-diaphysis; in situ visualization by MPM. The image shown is a 20 μm stacked Z-series. (B) Shows Active Mitochondrial Content of osteocytes in metatarsal mid-diaphysis as a function of location across the cortex. Data show mean ± SD for osteocytes through the cortical width, where 0% = periosteal surface and 100% = endocortical surface). Equation for the regression line show: y = 1.4534x−0.637, r2 = 0.70.

3.3 - Osteocyte Mitochondrial Content: ATPase-5A immunohistochemistry

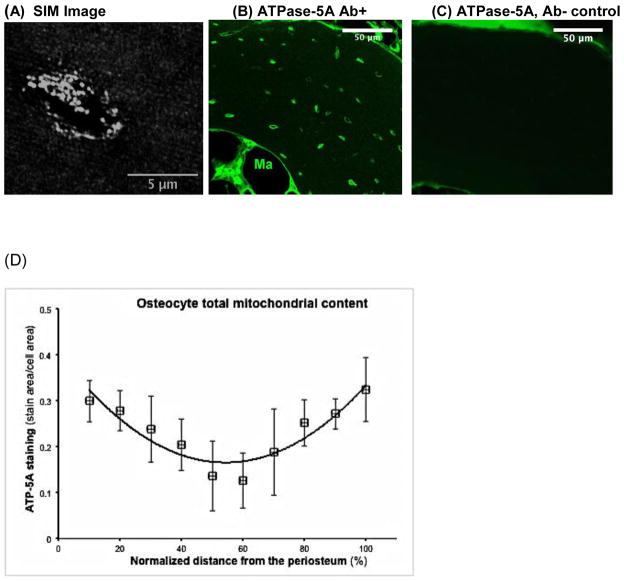

Analysis of fluorescent immunohistochemical staining of osteocytes for ATPase-5A by super resolution microscopy (Fig 6a) revealed well-delineated staining patterns in individual cells consistent with discrete mitochondria or mitochondrial clusters. Overall ATPase-5A staining intensity also differed depending on osteocyte location within the cortex (Fig 6b, c). Mitochondrial content was highest in osteocytes near both the periosteal and endosteal surfaces, and lower by an average of 70% near the middle of the cortex (Fig 6d), similar to that observed for Active Mitochondrial Content (Fig 5). However, in contrast to active mitochondria, the total mitochondrial content rose near the endosteal surface. The spatial distribution of total mitochondrial content in osteocytes followed a binomial function (Fig 6).

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial content of cortical osteocytes assessed by ATPase-5A immunohistochemistry and Super Resolution Microscopy (SIM mode). (A) SIM image of an ATPase-5A-stained osteocyte-showing individual and clustered mitochondria. (B) Lower magnification confocal image of ATPase-5A stained metatarsal diaphyseal cross-section. Ma point to marrow cavity (C) Non-immune serum control section showing nonspecific staining in the periosteum and endosteum. (D) Distribution of osteocyte mitochondrial content throughout the metatarsal cortical width. Data show mean ± SD for osteocyte mitochondrial context (%ATPase-5A staining) through the cortical width, where 0% = periosteal surface and 100% = endocortical surface). Equation for the regression shown: y = 8 × 10−5 x2 - 0.0088x + 0.4038, r2 = 0.85

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate using mulitiphoton microscopy in vivo, mitochondrial functional dyes and immunohistochemistry that cortical bone osteocytes exhibit marked spatial heterogeneity in mitochondrial content and activity, and in their redox response to hypoxic stress as well. Both total and active mitochondrial content were high in osteocytes near the periosteal surface and low in osteocytes nearer to the mid-cortex. In addition, osteocytes deeper in the cortex required roughly twice as long to begin accumulating NADH after postmortem ischemia. By contrast, total mitochondrial content was high in osteocytes near the endosteal cortical surface, but active mitochondrial content remained at low levels similar to those in mid-cortex, indicating a larger proportion of poorly functional mitochondria. Since the endosteal region of the cortex is also the site where increased osteocyte apoptosis has been observed following ovariectomy [4] and unloading [6], this finding supports the concept posited by Emerton [4] and Almeida [7] that diminished mitochondrial function may contribute to the susceptibility of osteocytes to undergo apoptosis in response to bone remodeling stimuli.

In vivo evaluation of NADH levels in metatarsal osteocytes established that they do not exist in a hypoxic state. The absence of endogenous NADH fluorescence in osteocytes under basal conditions clearly demonstrates that the nicotinamide redox cofactors in osteocytes exist almost exclusively in their oxidized forms (e.g. as NAD+) and that any NADH produced by nutrient catabolism is rapidly re-oxidized. The rise in NADH fluorescence when oxygen supplies were cut off due to post-mortem ischemia further indicates that aerobic (i.e. mitochondrial) mechanisms are probably responsible for most NADH re-oxidation. Shapiro et al also showed that bone and calcified cartilage of chick epiphysis exhibited minimal NADH fluorescence, in contrast to resting and proliferative cartilage, where higher fluorescence levels resembled those of other tissues where oxygen is limiting [36]. Taken together, these findings indicate that aerobic oxidative mechanisms likely comprise the primary pathway of ATP generation by metatarsal cortical bone osteocytes under basal conditions.

Critically, we observed that the acute immobilization of the bone for up to 4 hours of anesthesia did not affect osteocyte NADH levels, i.e, they did not develop mitochondrial stress. These data indicate that the absence of convective fluid flow in the osteocyte lacunar-canalicular system (LCS) due to the lack of mechanical loading (i.e., the acute immobilization) did not impair oxygen transport to osteocytes. These results are consistent with in vivo LCS tracer studies showing that solutes under 1 kDa or roughly 1 nm diameter (e.g. steroid hormones, glucose, ATP, NO, CO2, O2) move easily by diffusion in the fluid spaces of bone, independent of convective transport [37–39].

Imposition of severe hypoxia, however, led to increase in osteocyte NADH content that differed regionally even though all osteocytes exhibited similarly low levels of reduced pyridine nucleotides under baseline conditions. Osteocytes nearer the periosteum reached peak NADH fluorescence in response to severe hypoxia twice as fast as those in mid-cortex. The time of onset of NADH accumulation following acute ischemia reflects the time required to deplete the cellular oxygen supply, blocking the electron transport chain reactions that regenerate NADH. The regional disparity in NADH accumulation we observed suggests that oxygen supplies are depleted fastest at sites nearest to the periosteal bone surface. This may in part be due to regional differences in the number of cells, but also appears to arise in part from intrinsic differences in the oxidative capacity of the osteocyte populations. TMRM staining and traditional immunohistochemistry indicated greater content of active and total mitochondria, respectively, in osteocytes closer to the periosteum than in those near the mid-cortex. Changes in NADH levels would then depend largely by the balance between catabolic reactions that produce NADH and anaerobic pathways that re-oxidize it (e.g. lactate production from pyruvate). The late declines in NADH fluorescence that we observed indicate that the buildup of reduced pyridine nucleotides dissipates quickly in both osteocyte populations as cells adjust to a new anaerobically-based metabolism.

In vivo, real-time detection of endogenous pyridine nucleotide fluorescence by multiphoton microscopy could only be carried out on osteocytes at depths corresponding to roughly half the cortical width of the metatarsal bones. However, it was possible to assess the osteocyte oxidative capacity, reflected by total and active mitochondrial content, throughout the full width of the cortex. Traditional IHC was used to detect ATPase-5A (an indicator of total osteocyte mitochondrial content) and ex-vivo imaging of TMRM in fresh metatarsal transverse cross sections was used to visualize active mitochondrial content.

Staining for ATPase-5A by IHC and visualization with SIM super-resolution microscopy revealed that total mitochondrial content of metatarsal osteocytes near endosteal as well as periosteal surfaces was greater than that in mid-cortex. The concept of heterogeneity in osteocytes mitochondrial content function of their location was first proposed by Belanger et al more than 40 years ago. From transmission electron microscopy studies, they found that the older osteocytes that occupy the deeper cortical regions had fewer mitochondria that those nearer to the periosteal surface, and suggested that the loss of mitochondria in these older cells reflected differences in metabolism. Our results are consistent with this idea. Moreover, our data argue that osteocytes with greater mitochondrial content are located nearer to the sources of tissue oxygen: namely, the periosteal and endosteal bone surfaces whose separate vascular supplies nourish the outer and inner portions of the cortex, respectively [40]. Li et al [41] using radiolabeled microspheres showed that the rates of blood flow to periosteal cortical bone and endocortical bone were very similar, approximately 4.5 ml/min/100g of bone. However, blood supply to the middle of the cortex is lower than the surface associated regions. Changes in superficial osteocyte NADH accumulation that we observed following ischemia and its resultant hypoxic state were similar in timing and magnitude to those widely reported for skin [28], liver [42], brain [43] and other highly aerobic tissues subjected to hypoxia. We did not directly address whether the oxygen tension differs regionally within the cortex. However, the markedly greater resistance of mid-cortex osteocytes to hypoxic stress certainly suggests that these deeper-living osteocytes have adapted to a less oxygen-rich environment. Borle et al [44], Cohn et al [45] in the 1960’s showed that bone cells contain the enzyme systems required for anaerobic glycolysis. Our data also agree with the more recent findings reported to Guo et al [21] who reported that osteocytes more deeply located in bone express the chaperone protein ORP150, which counteracts hypoxia-induced cell death [46], providing a parallel line of evidence that internal osteocytes may exist in a less oxygen-rich environment.

Given that total mitochondrial content in osteocytes varied spatially across the cortex apparently in direct relation to with tissue oxygen levels, the disparity in functional (active) mitochondrial content between osteocytes near periosteal and endosteal surfaces was striking. It is unlikely that the difference was an artifact related to the use of ex vivo rather than in vivo approaches, as both yielded the same pattern of TMRM staining in the periosteal half of the cortex (data not shown). The data suggest that while the total mitochondrial content of osteocytes near the endosteal surface is higher than in mid-cortex, many of those mitochondria are poorly functional, since they fail to sustain electrochemical gradients detectable by TMRM [47]. Why this occurs is unclear, but one possibility is that damaged mitochondria accumulate in this region, either because the rate of damage (from mechanisms unknown) is unusually high or the cell’s ability to remove the damaged organelles is locally diminished. Regional differences in autophagic (mitophagic) mechanisms responsible for mitochondrial turnover could be at least partly responsible for the observed pattern. Several studies have provided evidence that defects in autophagic pathways are associated with increased osteocyte apoptosis [48] and bone loss [49, 50]. But in any case, the cortical region near the endosteal surface, where an increased proportion of poorly functional mitochondria are found, coincides with the site where increased osteocyte apoptosis has been demonstrated in response to both ovariectomy [4] and disuse [6]. The fact that increased osteocyte apoptosis in response to these global stimuli was not seen in mid-cortical or periosteal regions of the cortex suggests that changes in mitochondrial content per se do not foster cell death, provided that mitochondrial functionality is maintained.

Oxidative stress has been viewed as a substantial contributor to osteocyte apoptosis in instances where increased bone resorption occurs. Almeida et al [51] found that estrogen withdrawal caused oxidative stress (increased ROS-levels) in bone cells. Emerton et al [4] in our laboratory found that the cortical bone osteocytes undergoing apoptosis after estrogen loss were the most poorly perfused and/or the oldest cells and suggested that removal of the protective effect of estrogen on mitochondrial functions caused the most oxidatively stressed osteocytes to die. Gross et al [43] observed that disuse resulted in upregulation of HIF-1α in osteocytes, which suggested local hypoxia and oxidative stress resulted from the absence of mechanical loading and LCS fluid flow. This oxidative stress has been posited to contribute to the osteocyte apoptosis in disuse [52]. However, the current studies as well as those by Frangos and colleagues [8] demonstrate, respectively, that diffusion of small molecules like oxygen are largely unaffected in disuse despite disturbances in convective flow. The resolution of this paradox may lie in the recent data, which indicates that HIF-1α expression is triggered by a broad range of cell stresses in addition to hypoxia [53]. The precise stressor leading to the HIF-1α in osteocytes in disuse is not known. However, loss of mechanical loading will impair transport of larger molecules (growth factors, cytokines) that are highly dependent on convective flow for movement to and from osteocytes through the LCS [37, 38]. Many of these molecules are essential for cell health, thus it seems reasonable to speculate that loss of such key regulatory molecules leads to osteocyte stress.

In summary, the present study utilized novel in vivo and in situ imaging approaches based on multiphoton microscopy to demonstrate that osteocyte oxidative metabolism in cortical bone differs depending on location within the tissue. In the mouse metatarsals studied here, we were able to observe osteocytes lying as deep as the mid-cortical “watershed” region halfway between endocortical and periosteal surfaces in vivo and in real time. We found that all diaphyseal osteocytes in this region depend heavily on aerobic (mitochondrial) oxidative pathways but that osteocyte response to oxidative stress depends on their distance from the periosteal surface. We also established, using a combination of vital mitochondrial activity dyes and traditional IHC visualized by super resolution microscopy, that these regional differences in oxidative function relate to differences in total and active mitochondrial content among osteocytes. There studies further demonstrated that osteocytes near the endosteal surface, where increased apoptosis has been observed following bone resorptive stimuli, appear to contain a high proportion of poorly functional mitochondria. Accordingly, it seems reasonable to posit that these regional differences in osteocyte oxidative metabolism, as well as mitochondrial content and activity, will influence whether osteocytes will survive or undergo apoptosis in response to these and other environmental stressors. The MPM-based approaches developed in this study offer new and sensitive ways to interrogate these relationships.

Highlights.

Osteocyte oxidative metabolism assessed in cortical bone by in situ imaging

Both mitochondrial content and response to hypoxia differ with location in cortex

Total mitochondrial content high near bone surfaces but low in mid-cortex

Active mitochondrial content high only in osteocytes near periosteum

Endosteal osteocytes may contain a high proportion of nonfunctional mitochondria

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants AR041210 and AR057139 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Damien Laudier for expert assistance with the IHC studies. We thank Dr. Adrian Rodriguez-Contreras for allowing use of the multiphoton microscopy. DF-B received partial support from a doctoral fellowship from the Grove School of Engineering at the City College of New York.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kennedy OD, Herman BC, Laudier DM, Majeska RJ, Sun HB, Schaffler MB. Activation of resorption in fatigue-loaded bone involves both apoptosis and active pro-osteoclastogenic signaling by distinct osteocyte populations. Bone. 2012;50(5):1115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso L, Herman BC, Verborgt O, Laudier D, Majeska RJ, Schaffler MB. Osteocyte apoptosis controls activation of intracortical resorption in response to bone fatigue. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(4):597–605. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguirre JI, Plotkin LI, Stewart SA, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Osteocyte Apoptosis Is Induced by Weightlessness in Mice and Precedes Osteoclast Recruitment and Bone Loss. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(4):495–655. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emerton KB, Hu B, Woo AA, Sinofsky A, Hernandez C, Majeska RJ, Jepsen KJ, Schaffler MB. Osteocyte apoptosis and control of bone resorption following ovariectomy in mice. Bone. 2010;46(3):577–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomkinson A, Reeve J, Shaw RW, Noble BS. The Death of Osteocytes via Apoptosis Accompanies Estrogen Withdrawal in Human Bone. J Clin EndocrinolMetab. 1997;82(9):3128–35. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.9.4200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabahug-Zuckerman P, Frikha-Benayed D, Majeska RJ, Tuthill A, Yakar S, Judex S, Schaffler MB. Osteocyte Apoptosis Caused by Hindlimb Unloading is Required to Trigger Osteocyte RANKL Production and Subsequent Resorption of Cortical and Trabecular Bone in Mice Femurs. J Bone Miner Res. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, Plotkin LI, Stewart SA, Roberson PK, Kousteni S, O’Brien CA, Bellido T, Parfitt AM, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC. Skeletal involution by age-associated oxidative stress and its acceleration by loss of sex steroids. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(37):27285–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702810200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verborgt O, Gibson GJ, Schaffler MB. Loss of Osteocyte Integrity in Association with Microdamage and Bone Remodeling After Fatigue In Vivo. J Bone MinerRes. 2000;15(1):60–7. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tami AE, Nasser P, Verborgt O, Schaffler MB, Knothe Tate ML. The role of interstitial fuid flow in the remodeling response to fatigue loading. J Bone MinerRes. 2002;17(11):2030–2037. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.11.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens HY, Meays DR, Frangos JA. Pressure gradients and transport in the murine femur upon hindlimb suspension. Bone. 2006;39(3):565–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross TS, Nagako A, Thomas LC, Svetlana K, Sundar S, David AW, Sergey M. Physiological and Genomic Consequences of Intermittent Hypoxia Selected Contribution- Osteocytes upregulate HIF-1a in response to acute disuse and oxygen deprivation. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2514–2519. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma D, Ciani C, Marin PA, Levy JD, Doty SB, Fritton SP. Alterations in the osteocyte lacunar-canalicular microenvironment due to estrogen deficiency. Bone. 2012;51(3):488–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soustiel JF, Palzur E, Nevo O, Thaler I, Vlodavsky E. Neuroprotective anti-apoptosis effect of estrogens in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22(3):345–52. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campos C, Casali KR, Baraldi D, Conzatti A, Araujo AS, Khaper N, Llesuy S, Rigatto K, Bello-Klein A. Efficacy of a low dose of estrogen on antioxidant defenses and heart rate variability. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:218749. doi: 10.1155/2014/218749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JQ, Cammarata PR, Baines CP, Yager JD. Regulation of mitochondrial respiratory chain biogenesis by estrogens/estrogen receptors and physiological, pathological and pharmacological implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793(10):1540–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang YB, Zhong ZM, Hou G, Jiang H, Chen JT. Involvement of oxidative stress in age-related bone loss. J Surg Res. 2011;169(1):e37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller FL, Lustgarten MS, Jang Y, Richardson A, Van Remmen H. Trends in oxidative aging theories. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43(4):477–503. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jande SS, Bélanger LF. The life cycle of the osteocyte. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;94:281–305. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197307000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin JH, Matthews JL. Mitochondrial granules in chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteocytes. An ultrastructural and microincineration study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970 Jan-Feb;68:273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baud CA. Submicroscopic structure and functional aspects of the osteocyte. ClinOrthop Relat Res. 1968;56:227–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo D, Keightley A, Guthrie J, Veno PA, Harris SE, Bonewald LF. Identification of osteocyte-selective proteins. Proteomics. 2010;10(20):3688–98. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chance B. Spectra and Reaction Kinetics of Respiratory Pigments of Homogenized and Intact Cells. Nature. 1952;169:215–221. doi: 10.1038/169215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Q, Heikal AA. Two-photon autofluorescence dynamics imaging reveals sensitivity of intracellular NADH concentration and conformation to cell physiology at the single-cell level. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2009;95(1):46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasischke KA, Vishwasrao HD, Fisher PJ, Zipfel WR, Webb WW. Neural activity triggers neuronal oxidative metabolism followed by astrocytic glycolysis. Science. 2004;305(5680):99–103. doi: 10.1126/science.1096485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang S, Heikal AA, Webb WW. Two-Photon fluorescence spectroscopy and microscopy of NAD(P)H and flavoprotein. Biophys J. 2002;82(5):2811–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75621-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothstein EC, Carroll S, Combs CA, Jobsis PD, Balaban RS. Skeletal muscle NAD(P)H two-photon fluorescence microscopy in vivo: topology and optical inner filters. Biophys J. 2005;88(3):2165–76. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.053165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skala MC, Riching KM, Gendron-Fitzpatrick A, Eickhoff J, Eliceiri KW, White JG, Ramanujam N. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of NADH and FAD redox states, fluorescence lifetimes, and cellular morphology in precancerous epithelia. ProcNatl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19494–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708425104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palero JA, de Bruijn HS, van der Ploeg-van den Heuvel A, Sterenborg HJ, Gerritsen HC. In vivo nonlinear spectral imaging in mouse skin. Opt Express. 2006;14(10):4395–402. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.004395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Christie R, Nikitin AY, Hyman BT, Webb WW. Live tissue intrinsic emission microscopy using multiphoton-excited native fluorescence and second harmonic generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(12):7075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832308100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoumi A, Yeh A, Tromberg BJ. Imaging cells and extracellular matrix in vivo by using second-harmonic generation and two-photon excited fluorescence. ProcNatl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(17):11014–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172368799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radosevich AJ, Bouchard MB, Burgess SA, Chen BR, Hillman EM. Hyperspectral in vivo two-photon microscopy of intrinsic contrast. Opt Lett. 2008;33(18):2164–66. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.002164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palero JA, Bader AN, de Bruijn HS, der Ploeg van den Heuvel Av, Sterenborg HJ, Gerritsen HC. In vivo monitoring of protein-bound and free NADH during ischemia by nonlinear spectral imaging microscopy. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2(5):1030–1039. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall AM, Rhodes GJ, Sandoval RM, Corridon PR, Molitoris BA. In vivo multiphoton imaging of mitochondrial structure and function during acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):72–83. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heywood HK, Knight MM, Lee DA. Both superficial and deep zone articular chondrocyte subpopulations exhibit the Crabtree effect but have different basal oxygen consumption rates. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223(3):630–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gustafsson MG. Nonlinear structured-illumination microscopy: Wide-field fluorescence imaging with theoretically unlimited resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2005;102(37):13081–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406877102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shapiro IM, Golub EE, Kakuta S, Hazelgrove J, Havery J, Chance B, Frasca P. Initiation of endochondral calcification is related to changes in the redox state of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Science. 1982;217(3):950–952. doi: 10.1126/science.7112108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, You L, Schaffler MB, Wang L. The dependency of solute diffusion on molecular weight and shape in intact bone. Bone. 2009;45(5):1017–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.07.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price C, Zhou X, Li W, Wang L. Real-time measurement of solute transport within the lacunar-canalicular system of mechanically loaded bone: direct evidence for load-induced fluid flow. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(2):277–85. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L, Wang Y, Han Y, Henderson SC, Majeska RJ, Weinbaum S, Schaffler MB. In situ measurement of solute transport in the bone lacunar-canalicular system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(33):11911–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505193102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trias A, Fery A. Cortical circulation of long bones. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(7):1052–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li G, Bronk JT, Kelly PJ. Canine bone blood flow estimated with microspheres. J orthop Res. 1989;7:61–67. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obi-Tabot ET, Hanrahan LM, Cachecho R, Beer ER, Hopkins SR, Chan JC, Shapiro JM, LaMorte WW. Changes in hepatocyte nadh fluorescence during prolonged hypoxia. J Surg Res. 1993;55(6):575–80. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1993.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foster KA, Beaver CJ, Turner DA. Interaction between tissue oxygen tension and NADH imaging during synaptic stimulation and hypoxia in rat hippocampal slices. Neuroscience. 2005:132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borle AB, Nicols N, Nicols G. Metabolic studies of bone in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:1206–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohn DV, Forscher BK. Effect of parathyroid extract on the oxidation in vitro of glucose and the production of co2 by bone and kidney. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1962;65:20–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(62)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozawa K, Kuwabara K, Tamatani M, Takatsuji K, Tsukamoto Y, Kanedai S, Yanagii H, Stern DM, Eguchi Y, Tsujimoto Y, Ogawa S, Tohyama M. 150-kDa Oxygen-regulated Protein (ORP150) Suppresses Hypoxia-induced Apoptotic Cell Death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(10):6397–404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romanello V, Guadagnin E, Gomes L, Roder I, Sandri C, Petersen Y, Milan G, Masiero E, Del Piccolo P, Foretz M, Scorrano L, Rudolf R, Sandri M. Mitochondrial fission and remodelling contributes to muscle atrophy. EMBO J. 2010;29(10):1774–85. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Onal M, Piemontese M, Xiong J, Wang Y, Han L, Ye S, Komatsu M, Selig M, Weinstein RS, Zhao H, Jilka RL, Almeida M, Manolagas SC, O’Brien CA. Suppression of Autophagy in Osteocytes Mimics Skeletal Aging. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17432–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu F, Fang F, Yuan H, Yang D, Chen Y, Williams L, Goldstein SA, Krebsbach PH, Guan JL. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion leads to osteopenia in mice through the inhibition of osteoblast terminal differentiation. J Bone MinerRes. 2013;28(11):2414–30. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen K, Yang YH, Jiang SD, Jiang LS. Decreased activity of osteocyte autophagy with aging may contribute to the bone loss in senile population. Histochem Cell Biol. 2014;142(3):285–95. doi: 10.1007/s00418-014-1194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Almeida M, Martin-Millan M, Ambrogini E, Bradsher R, 3rd, Han L, Chen XD, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, O’Brien CA, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC. Estrogens attenuate oxidative stress and the differentiation and apoptosis of osteoblasts by DNA-binding-independent actions of the ERalpha. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(4):769–81. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaffler MB, Cheung WY, Majeska R, Kennedy O. Osteocytes: master orchestrators of bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;94(1):5–24. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9790-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Movafagh S, Crook S, Vo K. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a by reactive oxygen species: new developments in an old debate. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(5):696–703. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]