Abstract

Sanfilippo B syndrome is a progressive neurological disorder caused by inability to catabolize heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans. We studied neurobehavior in male Sanfilippo B mice and heterozygous littermate controls from 16–20 weeks of age. Affected mice showed reduced anxiety, with a decrease in the number of stretch-attend postures during the elevated plus maze (p = 0.001) and an increased tendency to linger in the center of an open field (p = 0.032). Water maze testing showed impaired spatial learning, with reduced preference for the target quadrant (p = 0.01). In radial arm maze testing, affected mice failed to achieve above-chance performance in a win-shift working memory task (t-test relative to 50% chance: p = 0.289), relative to controls (p = 0.037). We found a 12.4% reduction in mean acetylcholinesterase activity (p < 0.001) and no difference in choline acetyltransferase activity or acetylcholine in whole brain of affected male animals compared to controls. Cholinergic pathways are affected in adult-onset dementias, including Alzheimer disease. Our results suggest that male Sanfilippo B mice display neurobehavioral deficits at a relatively early age, and that as in adult dementias, they may display deficits in cholinergic pathways.

Keywords: mucopolysaccharidosis, lysosomal, neurodegeneration, acetylcholinesterase, glycosaminoglycan, inborn error of metabolism

1. Introduction

Sanfilippo B syndrome is a devastating neurological disorder of childhood [1,2]. The biochemical defect is deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase (Naglu), leading to accumulation of heparan sulfate throughout the body and brain [3]. Affected children experience progressive neurological deterioration and early death. Work by others showed that behavioral abnormalities in Sanfilippo children with the phenotypically-similar type A include a Klüver-Bucy like syndrome with reduced fearfulness [4,5]. This reduced fear response was found to correlate with volume loss in the amygdala [4]. The mouse model of Sanfilippo B was similarly found to demonstrate reduced fear, evidenced by increased time spent in the center of an open field [6].

While there are no available, effective treatments for Sanfilippo B, several promising therapeutic options have been explored in animal models [7–10]. Better characterization of the murine phenotype is needed in order to evaluate the effectiveness of potential therapies for neurological disease due to Sanfilippo B prior to translation to patients. The ideal phenotypic read-outs for preclinical therapeutic development would be detectable relatively early in life, in order to avoid age-associated physical disease that can confound neurobehavioral testing. These read-outs would also ideally not be overly dependent upon hearing and vision, both of which are abnormal in Sanfilippo B mice [11].

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Animals

Mutant male Sanfilippo B mice (B6.129S6-Naglutm1Efn/J backbred onto C57BL6/J; [6]; Naglu−/−) were mated with heterozygous females (Naglu+/−) to obtain homozygous affected mice and heterozygous controls. Genotype was performed with primers: NAG 5′: TGGACCTGTTTGCTGAAAGC; NAG 3′: CAGGCCATCAAATCTGGTAC; Neo 5′: TGGGATCGGCCATTGAACAA; Neo 3′: CCTTGAGCCTGGCGAACAGT. The design was cross-sectional. Male Sanfilippo B mice and controls were housed in groups of 4 mice/cage. Behavioral core personnel were blinded as to genotype of each cage. Data were entered on a coded spreadsheet, so that core laboratory staff remained blinded as to the group assignment of individual mice but could see group means and trends. The experiment began with n = 14 Sanfilippo B and n = 12 control mice. During neurobehavioral testing, two Sanfilippo B mice were excluded due to trauma from fighting, and one control mouse was excluded due to malocclusion and poor weight gain. For the radial arm maze, any mice that did not eat all of the pellets in phase 1 did not move on to phase 2 and were excluded from further analysis. The exact numbers of animals used in each experiment are indicated in the figures. Mice received ad libitum food and water (except when fasted for radial arm maze testing) and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and UCLA.

2.2. Neurobehavior

Mice were transferred to the UCLA Behavioral Testing Core at age of 16 weeks. After an acclimatization period of approximately 1 week, mice underwent behavioral testing from age 17–20 weeks in the following order: SHIRPA primary screen, elevated plus maze, rotarod, socialization approach test, open field test, novel object recognition test, Morris water maze (visible, then hidden), radial arm maze. Behavior was tracked via an overhead camera using Topscan automated behavioral analysis software (Clever Sys Inc., Reston, VA).

2.2.1. SHIRPA primary screen

A SHIRPA primary screen was performed to assess general health, gross hearing, vision and coordination, modified from [12]. The following behaviors were assessed over a period of approximately ten minutes for each mouse: body position, spontaneous activity, respiration rate, tremor, urination, defecation transfer arousal, locomotor activity, palpebral closure, piloerection, startle response, gait, pelvic elevation, tail elevation, touch escape, positional passivity, trunk curl, limb grasping, visual placing, whisker brush, whisker placement, grip strength, body tone, pinna reflex, corneal reflex, toe pinch, wire maneuver, body length, skin color, limb tone, abdominal tone, lacrimation, salivation, provoked biting, penlight vision, righting reflex, contact righting reflex, negative geotaxis, fear (present/absent), irritability, aggression, and vocalization.

2.2.2. Elevated plus maze

Mice were placed in a standard elevated plus maze apparatus for 5 minutes. The percent time in the open and closed arms and the number of stretch attend postures were tracked with automated behavioral tracking software.

2.2.3. Rotarod

To test balance (vestibular and cerebellar function), mice were studied on a Rotamex-5 rotarod (Columbus Instruments International, Columbus, OH). Rod speed was accelerated from an initial speed of 5 rpm to a maximum of 60 rpm over period of 300 s. The latency to fall and the final rpm were recorded.

2.2.4. Socialization approach test

We assessed the interaction of Sanfilippo B mice with same-sex, non-littermate, non-cagemate mice. This task utilized a three-chamber apparatus and procedures as described [13]. Briefly, mice were habituated to the three chamber apparatus for 10 minutes. Wire cups were then placed in the side chamber with a novel interaction mouse placed in one cup and no mouse placed in the other cup. Time spent in the two side chambers over a 10 minute test period was then tracked to determine the relative amount of time spent interacting with the interaction mouse vs. the empty cup. A preference ratio was calculated as: (time in mouse side - time in empty cup side)/(time in mouse side + time in empty cup side)*100.

2.2.5. Open field test

Activity in an open field was assessed over 10 min in a square plexiglass enclosure (27.5 cm × 27.5 cm) during light and dark as previously described [14]. Lights in the experimental room were on during the first 5 min (25 lux) and off during the second 5 min. Overall distance moved and time spent in the center was analyzed by automated behavioral analysis software.

2.2.6. Novel object recognition test

Mice also underwent a novel object recognition task utilizing the same open field apparatus described above. Dim lighting conditions (5 lux) were used across the three days of this test. Mice were habituated to the open field for 10 minutes on Day 1. On Day 2 two identical objects were placed in the open field in opposite corners 6 cm equidistant from the nearest two walls. Distance moved and object interaction was tracked over 10 minutes. The novel and familiar objects were 50 ml Erlenmeyer flasks that were either empty or contained green tissue paper (for half of the animals the filled flask was familiar and the empty flask was novel, for the other half of the animals this was reversed). On Day 3 the familiar object was switched with a novel object (counterbalanced across animals for which object was novel vs. familiar and which side of the arena the novel object was placed in). Distance moved and object interaction was tracked over 10 minutes.

2.2.7. Morris water maze

Mice were trained (4 training trials per day) in a custom water maze pool (122 cm diameter) at 24°C with an overhead camera. An escape platform in the center of one quadrant (target quadrant) was submerged under 1 cm of water that was made opaque using non-toxic tempura paint. The two trials within each block were separated by five minutes and the two blocks were separated by 2 hours. The mice were placed in the pool at one of three start locations at the center of each non-target quadrant, with the order of placement randomized each day. The latency to find the platform was tracked each day. Approximately 2 hours after the end of training on the 5th day the platform was removed and the mice were given a 60 second probe trial where percent quadrant occupancy was determined. Mice were then tested in the visible version where the escape platform is not submerged and is marked by a flag extending 10 cm above the platform (4 trials on Day 1 and 2 trials on Day 2).

2.2.8. Radial arm maze

The maze consisted of a center platform and 8 arms radiating outward. Prior to training food access was gradually restricted until mice reached 85% of their pre-restricted body weight. During the 5 pre-training days, mice were placed in the center of the radial arm maze with all 8 arms open and baited. Spatial working memory training was assessed in 2 phases per day over 3 days. During Phase 1, 4 arms were baited (other arms closed). The animal was placed in the center hub and allowed to enter the arms until either all the pellets were consumed or 5 min had elapsed. Only animals that ate all 4 pellets advanced to Phase 2 (4 control and 4 Sanfilippo B mice failed to advance). During the Phase 2, the alternate 4 arms were baited. The animal is returned to the center of the maze and all 8 doors were opened. The trial ended when either the animal had eaten all 4 of the reward pellets or 5 min has elapsed. The baiting pattern of the maze is pseudo-random (no more than 3 adjacent arms were baited during either phase) and was altered from session to session, as was the order in which the animals were run. Movements were tracked by an overhead camera and recorded by a human observer. An arm entry was scored when the animal reached the final 25% of the arm and consumed the reward. We assessed Phase 1 within-trial working memory errors (re-entry into an arm), and across-phase errors (entry into an arm that was baited in phase 1).

2.3. Biochemical assays

All chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise specified. For mice used in the behavioral experiment, whole brains were used. For the cohort of 24 mice used solely for biochemical analysis, brain samples of the additional 24 mice cohort were first cut into 2 mm thick coronal sections with an adult mouse brain slicer matrix (Zivic Instruments, Pittsburgh, PA) [8]. Coronal brain slice 3 (where 1 is most rostral) was used for biochemical assays. Brains were homogenized in 1x PAD buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 5.8, 0.02 % sodium azide, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Triton X-100). Protein concentration was estimated using the Bradford method and bovine serum albumin was used as a standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

2.3.1. AChE activity

AChE activity was estimated in brain homogenate described elsewhere [15] with minor modifications. Twenty μL homogenate was mixed with 200 μL reaction mix (0.33 mM dithiobisnitrobenzoic acid, 1 mM acetylthiocholine iodide and 1.33 μM tetraisopropylpyrophosphoramide) and the change in absorbance recorded every 2 minutes for 10 minutes at 412 nm in Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). AChE activity standard curve was established with AChE from electric eel and the results expressed as milliunits (mU) per minute per mg protein.

2.3.2. ChAT activity

ChAT activity was determined using a modified method [16]. In brief, 10 μL homogenate was incubated with 200 μL reaction buffer (25 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2; 0.31 mM acetyl-CoA; 50 mM choline chloride; 38 μM neostigmine methyl sulfate; 150 mM NaCl; 55 μM EDTA) at 37 °C for 20 min. After boiling at 100 °C for 2 min to stop the reaction, 40 μL distilled water was added and samples centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 2 minutes. Ten μL of 1 mM 4-dithiopyrimidine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added to 200 μL supernatants and absorbance recorded at 324 nm after 15 min incubation at room temperature. The standard curve was generated with acetyl-CoA and the results expressed as nmol acetyl-CoA per minute per mg protein.

2.3.4. Acetylcholine

Acetylcholine levels were measured using an Amplex Red assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), following the manufacturer’s instructions and normalized to protein.

2.4. Histology

We stained sections of affected and control female mice aged 41–42 weeks for AChE activity as published [17] with minor modifications. In brief, frozen brain sections on slides were incubated in enzymatic reaction solution (50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0; 4 mM cupric sulfate; 16 mM glycine; 4 mM acetyl thiocholine iodide; 86 μM ethopropazine) overnight. After rinsing with distilled water, the slides were developed for 10 min in 1% sodium sulfide at pH 7.5.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Comparisons were performed using one-way or two-way ANOVA as appropriate, as indicated for each test in the results. We used MANOVA to evaluate repeated measures, effect measured with univariate F-tests. Linear regression was performed using the least squares method with AChE activity as the independent variable. Pearson and Spearman correlations were examined between the cognitive measures (water maze and radial arm maze) and anxiety measures (open field and elevated plus maze). A discriminant analysis was performed with all measures that showed statistically significant intergroup differences to determine the extent to which these measures could reliably distinguish mutant from control mice. All data were analyzed using SYSTAT version 13 or SPSS version 20 and graphed using SigmaPlot 13 (Systat Corporation, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1. Sanfilippo B mice show normal rotarod performance and locomotion at 16–20 weeks of age

We assessed physical disease in order to exclude it as a confounder for neurobehavioral studies. A SHIRPA primary screen was normal in Sanfilippo B and control mice, and there were no intergroup differences in rotarod performance on any of the three days of testing or across days (Fig. 1A, overall significant improvement over days: F(2,42) = 192.39, p < 0.001, no genotype by repeated measures (day) interaction: F(2,42) = 1.812, p = 0.176, no overall effect of genotype: F(1,21) = 0.001, p = 0.977). Open field testing showed no overall differences in locomotion with both groups showing the normal reduction in exploratory activity over time (Fig. 1B, overall effect of minute: F(9,189) = 6.699, p < 0.001, no minute by genotype interaction: F(9,189) = 1.160, p = 0.323 and no overall effect of genotype: F(1,21) = 0.155, p = 0.698).

Figure 1.

Motor performance. (A) Rotarod testing in littermate controls (filled circles) and Sanfilippo B mice (open circles). RPM: revolutions per minute. (B) Open field locomotion testing (day 1). Experiment began in dark (shaded portion of graph), followed by light. Error bars represent SEM.

3.2. Sanfilippo B mice display decreased anxiety/fear

Sanfilippo B mice showed an increased propensity for the center of the field during open field testing, which may indicate reduced fear/anxiety (Fig. 2A; p = 0.016 for minute 1 and p = 0.031 for minute 3; MANOVA with univariate F-tests). This difference was only present during the dark phase of testing (dark: F(1,21) = 5.279, p = 0.032; light: F(1,21) = 1.289, p = 0.269). During the elevated plus maze (Fig. 2B), Sanfilippo B mice showed a reduction in the number of stretch attend postures (a normal fear pose) compared to controls (F(1,23) = 13.703, p = 0.001) and a trend towards spending a greater percent of their time in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (17.6 ± 2.83%) vs. controls (11.0 ± 1.55%; F(1,23) = 3.53; p = 0.073; ANOVA). Sanfilippo B mice showed an abnormal lack of anxiety when approaching a normal object or mouse, as evidenced by increased time spent with a novel mouse in the social interaction test during the first minute of exposure to it (Fig. 2C; F(1,21) = 14.1; p = 0.001; MANOVA with univariate F-tests) as well as a reduced latency to interact with the novel mouse (Control: 169 ± 26.6s; Sanfilippo B: 49.9 ± 24.5s; F(1,24) = 10.9; p = 0.003). The anxiety measures of percent time in the center (dark phase) and the percent open arm times were positively correlated (ρ = 0.516, p = 0.012). Social preference during the first minute and the reduced latency to interact with the novel mouse, though highly correlated with each other (r = −0.856, p < 0.001), were not significantly correlated with the other anxiety measures. This suggests caution in viewing this increased social approach behavior as a reduction in anxiety and/or that social anxiety and exploratory anxiety are mediated by different processes.

Figure 2.

Anxiety/fear testing. (A) Proportion of time spent in the center of an open field during dark and light phases in littermate controls (filled circles) and Sanfilippo B mice (open circles). (B) Dot density plot of the number of stretch attend postures (a fear response) in Sanfilippo B and control mice during elevated plus maze testing. (C) Ratio of time spent interacting with a novel mouse to total time during phase 3 of the social interaction test. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05.

3.3. Sanfilippo B mice show diminished learning and memory

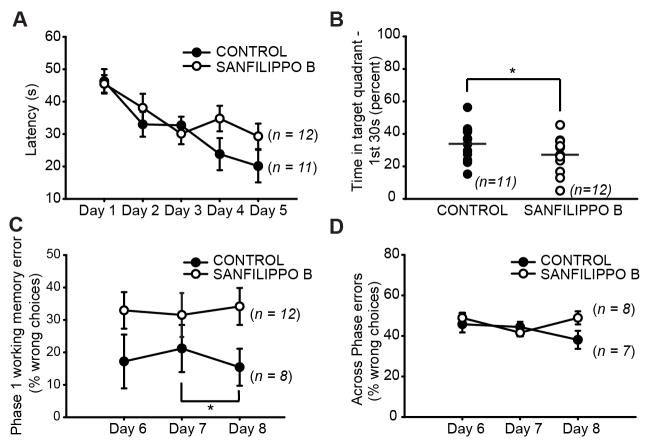

Morris water maze and radial arm maze were used to test visuospatial learning and memory in Sanfilippo B mice and controls. Differences in latency to find the hidden platform between Sanfilippo B and control mice did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3A; F(1,21) = 3.10; p = 0.093 by MANOVA with univariate F-tests). Sanfilippo B mice showed reduced percent time spent in the target quadrant during the first 30 s of the probe trials: 37.8 ± 3.86 percent vs. 22.7 ± 3.73 (Fig. 3B; F(1,21) = 7.93; p = 0.01 by ANOVA). The performance of Sanfilippo B mice was normal on a visible platform version of the water maze (not shown).

Figure 3.

Learning and memory. (A) Latency to find the hidden platform during Morris water maze testing in littermate controls (filled circles) and Sanfilippo B mice (open circles). Average of two trials per day is shown for days 1–4. Day 5 was a probe trial. (B) Time spent in the target quadrant during the first 30s in the Morris water maze. Symbols represent values of individual mice. Dashed lines represent group means. (C) Percent of choices that were incorrect during days 6–8 of phase 1 of radial arm maze testing. Bracket and asterisk indicate that control mice but not Sanfilippo B mice showed better than chance performance on the final day. (D) Across phase errors during days 6–8 of radial arm maze testing. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05.

In the radial arm maze, Sanfilippo B mice showed higher within-phase working memory errors compared to controls, but the results did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3C; MANOVA with univariate F-tests). Control mice showed an expected reduction in working memory errors over days (Fig. 3C; F(2,14) = 4.193, p = 0.037) reaching better than chance performance on the final day (t-test relative to 50% chance: p = 0.037). Sanfilippo B mice in contrast did not improve over days (F(2,12) = 1.379, p = 0.289) and were still at chance performance on the final day (t-test relative to 50% chance: p = 0.754). Between-groups analysis found a trend towards an increased number of across phase errors in Sanfilippo B mice on day 8 (F(1,13) = 4.03; p = 0.066 by MANOVA with univariate F-tests). There was a strong trend for an overall negative correlation between day 8 across phase working memory errors and target quadrant occupancy in the water maze (r = −0.471, p = 0.056) suggesting these two measures reflect the same underlying process.

A discriminant analysis was performed with percent center time during the dark phase (% Center), social preference in the first minute (SP), percent open arm time (%OA), stretch attend postures (SAP) and percent target quadrant occupancy in the water maze (%TQ). This yielded discriminant function coefficients of: % Center = 0.746, SP = 0.722, %OA = 0.165, %TQ = −0.721, SAP −0.370. These were highly effective at predicting the genotype (Wilks’ lambda = 0.284, p < 0.001) allowing for 100% correct predictions and 87% cross-validated leave-one-out classification.

3.4. Sanfilippo B mice show decreased activity of AChE in the brain

We found qualitatively decreased intensity of AChE staining in brains of Sanfilippo B mice (Fig. 4A, B). We found a 12% reduction in mean activity of AChE in Sanfilippo B mice compared to controls (Fig. 4C; F(1,22) = 25.1; p < 0.001 by ANOVA). ChAT, the enzyme that produces acetylcholine, was not significantly different in Sanfilippo B mice compared to controls (Fig. 4D), nor were there intergroup differences in acetylcholine levels (Fig. 4E). We analyzed coronal slices containing amygdala from 12 Sanfilippo B mice (6 males and 6 females) and 12 heterozygous controls (6 males and 6 females), aged 30.6–31.4 weeks. We found significant intergroup differences by genotype and by gender, with lower AChE values in Sanfilippo B mice compared to controls (F(1, 21) = 11.2; p = 0.003, two-way ANOVA), and lower AChE values in female compared to male mice (F(1,21) = 12.2; p = 0.002, two-way ANOVA). Subgroup analysis by gender reached statistical significance for males (F(1,10) = 7.20; p = 0.023, ANOVA; Fig. 4F). ChAT activity in section 3 of the brain showed a significant difference by gender (F(1,20) = 8.63; p = 0.008, two-way ANOVA) but not by genotype (F(1,20) = 2.21; p = 0.15, two-way ANOVA; Fig. 4G). Acetylcholine levels did not show intergroup differences either by genotype or by gender (two-way ANOVA; Fig. 4H). Linear regression analysis of behavioral variables in affected mice showed no correlation with AChE levels in whole brain (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 4.

Acetylcholinesterase and choline acetyltransferase activity in brain. (A–B) Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity staining (brown) in coronal sections of (A) control and (B) Sanfilippo B mice (representative of n = 3 per group). AG: amygdala; H: hippocampus. (C–H) Enzymatic activity of AChE and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) and acetylcholine levels in (C–E) whole brain homogenates and (F–H) coronal section 3 of the brain. Box plots show median, 25th and 75th centiles, and whiskers represent 5th and 95th centiles. Dot plots show values for individual mice. Dashed lines show group means. *p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The purpose of our experiment was to evaluate the neurobehavior of Sanfilippo B mice using methods that would be best suited for preclinical development of brain-directed therapies. We selected an age of the mice at which there is little physical disease, as evidenced by a normal rotarod performance [11]. We also selected behavioral tests that were not dependent upon auditory stimuli, as Sanfilippo B mice show abnormal hearing from a very early age [11]. Likewise, we were careful not to select tests that were overly dependent upon visual discrimination. Our study of neurobehavior focused only on male mice, to avoid the confounding influence of gender on behavior. Langford-Smith and colleagues found that female mice with Sanfilippo type A showed a more abnormal phenotype than their male counterparts [18].

Children with Sanfilippo syndrome demonstrate social-emotional and executive dysfunction, reduced fearfulness, increased activity, and impulsive behavior [19]. Autistic-like behavior also occurs and increases with age [20]. Deficits in learning and memory, as well as reduced fearfulness, have been described in mouse models of Sanfilippo types A, B and C [21–25]. We found reduced fearfulness in Sanfilippo B mice, as evidenced by increased time spent in the center of an open field, reduced stretch attend postures in the elevated plus maze, and decreased reluctance to approach a novel mouse during the social interaction test. We were not able to find a prior description of the social interaction test in Sanfilippo mice. Cressant and colleagues studied mice with Sanfilippo type A in the elevated plus maze, and found that affected mice spent more time in the open arms of the maze consistent with reduced anxiety [21]. In contrast, Fu and colleagues did not find abnormalities in the elevated plus maze in 5 month-old Sanfilippo B mice, but stretch attend postures were not reported [26]. Li and colleagues evaluated open field behavior in male and female mice and found reduced cross-overs in mutant mice at 4.5 months of age [6]. Langford-Smith and colleagues found that 8 month-old Sanfilippo B mice showed more center entries and increased path length in the center of an open field than wild-type mice, but did not show an increase in the overall time spent in the center in contrast to our results [27].

We found AChE deficiency in the brains of Sanfilippo B mice. A literature search revealed one case report describing AChE and ChAT deficiency that was found postmortem in an eight-year old boy with Sanfilippo type A syndrome [28]. Decreased AChE and ChAT activity occurs in Alzheimer disease and other dementias due to loss of cholinergic neurons [29]. In Sanfilippo B mice AChE, but not ChAT or acetylcholine, were deficient in affected mice. Our mice were relatively young, and it is possible that cholinergic pathway abnormalities may increase with age. Alternatively, Sanfilippo syndrome may cause a specific deficiency of AChE. AChE can be found in the neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques of Alzheimer disease along with heparan sulfate, which is the primary substrate that accumulates in Sanfilippo syndromes [30,31]. However, there is no known direct interaction between AChE and heparan sulfate or other known mechanism that would explain its specific reduction in Sanfilippo B mice. We did not study other neurotransmitters, so we do not know whether Sanfilippo B mice show a specific cholinergic deficit or whether the AChE deficiency that we found reflects broader synaptic dysfunction. We do not know what, if any, impact AChE deficiency has on the phenotype of Sanfilippo B syndrome. We did not find correlation between AChE activity in whole brain and behavioral outcomes in Sanfilippo B mice. However, we did not study the relationship between behavior and AChE activity in specific structures (such as the amygdala) because we did not collect them in our behavioral cohort. Patients with Sanfilippo A syndrome show a Kluver-Bucy-like syndrome that correlates with rapid decline in amygdala volume, but we also did not study amydgala volume here [4]. Our results suggest that male Sanfilippo B mice display neurobehavioral deficits at a relatively early age, and that as in adult dementias, they may display deficits in cholinergic pathways.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We studied behavior and cholinergic pathways in male Sanfilippo B mice.

We found reduced fearfulness and abnormal social interaction in Sanfilippo B mice.

These occurred early in the disease, before hearing and vision loss are expected.

We found reduced acetylcholinesterase activity in the brain of Sanfilippo B mice.

The findings further link Sanfilippo B syndrome with adult-onset dementias.

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by 1R01 NS088766, 1R01 NS043205 (to M.S.S.), UCLA CTSI Grant UL1TR000124 through a core voucher award, the UCLA Brain Research Institute, and a traineeship from 5T32 GM8243-28 (to S.-h.K.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Patricia I. Dickson receives research support from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. and Shire. Mark Sands receives research support from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.

Abbreviations

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- ChAT

choline acetyltransferase

- Naglu

alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wijburg FA, Węgrzyn G, Burton BK, Tylki-Szymańska A. Mucopolysaccharidosis type III (Sanfilippo syndrome) and misdiagnosis of idiopathic developmental delay, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder or autism spectrum disorder. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:462–470. doi: 10.1111/apa.12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valstar M, Ruijter G, van Diggelen O, Poorthuis B, Wijburg F. Sanfilippo syndrome: A mini-review. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:240–252. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0838-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao HG, Li HH, Bach G, Schmidtchen A, Neufeld EF. The molecular basis of Sanfilippo syndrome type B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6101–6105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potegal M, Yund B, Rudser K, Ahmed A, Delaney K, Nestrasil I, et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIA presents as a variant of Klüver-Bucy syndrome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35:608–616. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.804035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro E, King K, Ahmed A, Rudser K, Rumsey R, Yund B, et al. The neurobehavioral phenotype in mucopolysaccharidosis Type IIIB: An exploratory study. Mol Genet Metab Reports. 2016;6:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li HH, Yu WH, Rozengurt N, Zhao HZ, Lyons KM, Anagnostaras S, et al. Mouse model of Sanfilippo syndrome type B produced by targeted disruption of the gene encoding alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14505–14510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu H, DiRosario J, Kang L, Muenzer J, McCarty DM. Restoration of central nervous system alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase activity and therapeutic benefits in mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB mice by a single intracisternal recombinant adeno-associated viral type 2 vector delivery. J Gene Med. 2010;12:624–633. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kan S, Aoyagi-Scharber M, Le SQ, Vincelette J, Ohmi K, Bullens S, et al. Delivery of an enzyme-IGFII fusion protein to the mouse brain is therapeutic for mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:14870–14875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416660111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heldermon CD, Ohlemiller KK, Herzog ED, Vogler C, Qin E, Wozniak DF, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of bone marrow transplant, intracranial AAV-mediated gene therapy, or both in the mouse model of MPS IIIB. Mol Ther. 2010;18:873–880. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribera A, Haurigot V, Garcia M, Marcó S, Motas S, Villacampa P, et al. Biochemical, histological and functional correction of mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIB by intra-cerebrospinal fluid gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:2078–2095. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heldermon CD, Hennig AK, Ohlemiller KK, Ogilvie JM, Herzog ED, Breidenbach A, et al. Development of sensory, motor and behavioral deficits in the murine model of Sanfilippo syndrome type B. PLoS One. 2007;2:e772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers DC, Fisher EM, Brown SD, Peters J, Hunter AJ, Martin JE. Behavioral and functional analysis of mouse phenotype: SHIRPA, a proposed protocol for comprehensive phenotype assessment. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:711–713. doi: 10.1007/s003359900551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadler JJ, Moy SS, Dold G, Trang D, Simmons N, Perez A, et al. Automated apparatus for quantitation of social approach behaviors in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godsil BP, Stefanacci L, Fanselow MS. Bright light suppresses hyperactivity induced by excitotoxic dorsal hippocampus lesions in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:1339–1352. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Feather-Stone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao LP, Wolfgram F. Spectrophotometric assay for choline acetyltransferase. Anal Biochem. 1972;46:114–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotactic coordinates. 4. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langford-Smith A, Langford-Smith KJ, Jones SA, Wynn RF, Wraith JE, Wilkinson FL, et al. Female mucopolysaccharidosis IIIA mice exhibit hyperactivity and a reduced sense of danger in the open field test. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro EG, Nestrasil I, Ahmed A, Wey A, Rudser KR, Delaney KA, et al. Quantifying behaviors of children with Sanfilippo syndrome: the Sanfilippo Behavior Rating Scale. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;114:594–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rumsey RK, Rudser K, Delaney K, Potegal M, Whitley CB, Shapiro E. Acquired autistic behaviors in children with mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1147–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cressant A, Desmaris N, Verot L, Brejot T, Froissart R, Vanier MT, et al. Improved behavior and neuropathology in the mouse model of Sanfilippo type IIIB disease after adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer in the striatum. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10229–10239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3558-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarty DM, DiRosario J, Gulaid K, Muenzer J, Fu H. Mannitol-facilitated CNS entry of rAAV2 vector significantly delayed the neurological disease progression in MPS IIIB mice. Gene Ther. 2009;16:1340–1352. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawley AC, Gliddon BL, Auclair D, Brodie SL, Hirte C, King BM, et al. Characterization of a C57BL/6 congenic mouse strain of mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA. Brain Res. 2006;1104:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau AA, Crawley AC, Hopwood JJ, Hemsley KM. Open field locomotor activity and anxiety-related behaviors in mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;191:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martins C, Hůlková H, Dridi L, Dormoy-Raclet V, Grigoryeva L, Choi Y, et al. Neuroinflammation, mitochondrial defects and neurodegeneration in mucopolysaccharidosis III type C mouse model. Brain. 2015;138:336–55. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu H, Kang L, Jennings JS, Moy SS, Perez A, DiRosario J, et al. Significantly increased lifespan and improved behavioral performances by rAAV gene delivery in adult mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB mice. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1065–1077. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langford-Smith A, Malinowska M, Langford-Smith KJ, Węgrzyn G, Jones S, Wynn R, et al. Hyperactive behaviour in the mouse model of mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB in the open field and home cage environments. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:673–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Federico A, Bartoccioni E, Massarelli R. Cerebral choline acetyltransferase and acetylcholinesterase activities in a Sanfilippo syndrome, in a myoclonic epilepsy and in various zones of the human newborn brain. Acta Neurol. 1978;33:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies P, Maloney AJF. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1976;2:1403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalaria RN, Kroon SN, Grahovac I, Perry G. Acetylcholinesterase and its association with heparan sulphate proteoglycans in cortical deposits of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 1992;51:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90482-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry G, Siedlak SL, Richey P, Kawai M, Cras P, Kalaria RN, et al. Association of heparan sulfate proteoglycan with the neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3679–3683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03679.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.