Abstract

Drug overdose is now the leading cause of injury-related mortality in the USA, but the prognostic utility of cardiac biomarkers is unknown. We investigated whether serum cardiac troponin I (cTnI) was associated with overdose mortality. This prospective observational cohort studied adults with suspected acute drug overdose at two university hospital emergency departments (ED) over 3 years. The endpoint was in-hospital mortality, which was used to determine test characteristics of initial/peak cTnI. There were 437 overdoses analyzed, of whom there were 20 (4.6 %) deaths. Mean initial cTnI was significantly associated with mortality (1.2 vs. 0.06 ng/mL, p <0.001), and the ROC curve revealed excellent cTnI prediction of mortality (AUC 0.87, CI 0.76–0.98). Test characteristics for initial cTnI (90 % specificity, 99 % negative predictive value) were better than peak cTnI (88.2 % specificity, 99.2 % negative predictive value), and initial cTnI was normal in only one death out of the entire cohort (1/437, CI 0.1–1.4 %). Initial cTnI results were highly associated with drug overdose mortality. Future research should focus on high-risk overdose features to optimize strategies for utilization of cTnI as part of the routine ED evaluation for acute drug overdose.

Keywords: Drug, Overdose, Mortality, Troponin, Biomarker

Introduction

Drug overdose is currently the leading cause of injury-related mortality in the USA, with nearly 100 deaths per day since 2007 [1]. The drug overdose death rate of 11.8 per 100,000-persons in 2007 was roughly three times the rate in 1991 [2]. In 2012, there were over 1.5 million drug exposures reported to poison control centers (PCC), of which over 10 % had moderate or major outcomes, while over 1500 (1 %) suffered fatalities that were judged to be exposure-related by the American Association of Poison Control Centers [3].

Clinical predictors of drug overdose-related mortality depend on a variety of factors related to each individual exposure; however, a final common pathway of in-hospital drug-induced cardiac arrest likely involves myocardial toxicity [4], as respiratory arrests are readily preventable in the hospital setting. Drug toxicity may cause myocardial injury through a variety of mechanisms, including but not limited to, myocardial oxygen supply/demand mismatch (e.g., coronary artery vasospasm) [5], ion-channel poisoning (e.g., digoxin) [6], as well as direct myocardial toxicity (i.e., through inhibition of intrinsic metabolic pathways such as oxidative phosphorylation) [7]. We previously demonstrated that myocardial injury is the most common major adverse cardiovascular event that occurs following acute drug overdose [8]. According to guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, the approach to patients with symptoms of drug-induced myocardial injury should differ in both diagnostic and therapeutic managements [9]. However, such guidelines rely upon expert consensus due to lack of evidence-based tools to risk-stratify and guide management.

Cardiac troponin I (cTnI) is a regulatory protein of the myocardial contractile apparatus which is released into the bloodstream following myocardial cell necrosis due to injury from both ischemia and drug-induced cardio toxicity [10]. Mechanisms and pathophysiology of drug-induced myocardial injury as outlined in the revised clinical classification of myocardial infarction [11] are summarized in Table 1. In addition, there are several non-cardiogenic causes for circulating cTnI elevation, including renal and pulmonary disease [12, 13]. Overdoses from some drugs, such as colchicine, may actually be risk stratified using cardiac biomarkers [14].

Table 1.

Proposed pathophysiology of drug overdose-related myocardial injury

| Mechanism of myocardial injury |

|---|

| Decreased myocardial oxygen supply |

| Coronary artery vasospasm |

| Dysrhythmia |

| Hypotension |

| Increased myocardial oxygen demand |

| Hypertension |

| Increased metabolism (e.g., hyperthermia) |

| Direct myocardial cell death |

| Inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation |

In 2010, the American College of Cardiology called for clinical research to improve the emergency cardiovascular care in special populations, including risk stratification of drug overdose patients [9]. We therefore planned this derivation study to characterize the prognostic utility of cardiac biomarkers to predict in-hospital mortality following acute drug overdose. We hypothesized that cTnI would independently predict undifferentiated drug overdose mortality in a heterogeneous emergency department (ED) patient population.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This observational cohort study was prospectively performed on consecutive adult (>18 years) ED patients with acute drug (prescription, over-the-counter, and illicit) overdose over 36 months (2009–2012). Two urban, tertiary-care hospitals (Mount Sinai Hospital, Elmhurst Hospital Center) were used for enrollment with EDs that have a combined annual visit volume in excess of 250,000 and are staffed 24 h per day with board-certified emergency physicians and cardiologists. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board for all participating institutions with a waiver of informed consent.

Study Population

Patients with suspected acute drug overdose were initially screened for inclusion by trained research assistants using one of the two triggers: [1] rounding with the ED attending physicians several times daily during normal business hours, or [2] by telephone referral of the case to the regional PCC that was staffed 24 h/day and 7 days/week by Certified Specialists in Poisoning Information. Reporting of suspected acute poisoning to the Poison Control Center in New York City is mandated by the local public health law [15].

Following screening, formal inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to determine whether patients would be analyzed for cardiac biomarkers. Patients were screened who met both of the following criteria: [1] acute presentation (within 24 h of exposure) and [2] suspected overdose (i.e., illicit drug dose sufficient to cause symptoms or any prescription drug exposure greater than its therapeutic dose). Exclusion criteria were the following: alternative diagnosis (e.g., trauma, infection, or anaphylaxis), nondrug overdose (e.g., plant), exposures limited to dermal or inhalational routes only, age <18 years, patients with incomplete outcome data (i.e., left against medical advice, transferred to an outside institution, or otherwise eloped from the hospital), prisoners, and patients with pre-hospital cardiac arrest or do-not-resuscitate orders.

Measurements

Data collection from the medical chart occurred in accordance with accepted guidelines for valid medical chart abstraction, including training of abstractors and 95 % agreement of a random sampling of ten test charts prior to mass data abstraction [16]. Data deemed to be possible confounders for any association between cTnI results and mortality were abstracted to a de-identified electronic database with password protection and included urine cocaine metabolite, vital signs, and prior CAD. Toxicology screens other than cocaine metabolite are not considered as clinically reliable, were not routinely sent as part of clinical care, and were thus not considered in the present analysis.

Cardiac Biomarkers

Traditional cardiac biomarkers, drawn upon initial presentation to the ED, were measured using Bayer reagents (Bayer Healthcare, Cambridge, MA) on the Bayer Advia Centaur analyzer. The standard cutoff concentration was used for cardiac troponin I (0–0.09 ng/mL, detection limit 0.01 ng/mL, 10 % imprecision, 99th percentile cutoff >0.1 ng/mL). Repeat cardiac biomarkers were drawn as deemed necessary by the primary clinical team as part of routine care. Subjects without a laboratory evaluation of cTnI were recorded as “missing” (i.e., excluded) for the purposes of this analysis to avoid misclassification bias. Myocardial injury was defined as cTnI>0.09 ng/mL at any point in the hospital course. Peak troponin was defined as the highest measured cTnI at any point during the index hospital admission.

Study Protocol and Outcome

Subjects were prospectively followed to hospital discharge with hospital medical record follow-up for all patients performed by research assistants trained in medical abstraction and recorded using standardized data collection forms. Patients discharged from the hospital had no further follow-up. The study outcome was in-hospital all-cause mortality, which was used to determine test characteristics of cTnI.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-squared (with Fisher’s exact test when appropriate) and t test were calculated for categorical and continuous variables, respectively, with 5 % alpha (two-tailed). Independent prognostic utility of cTnI was assessed using multivariable logistic regression (model fit via Nagelkerke R2, listwise deletion of missing data, no interaction terms) for both the main analysis and sensitivity analysis. Optimal cTnI cutpoints for cTnI were determined using area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristics (ROC). Diagnostic test characteristics, including odds ratios (OR), were calculated with 95 % confidence intervals (CI). Computer analysis was performed with SPSS version 21.0, IBM, Chicago, IL.

Sample Size

Sample size was calculated a priori. Assuming 5 % prevalence of myocardial injury, we calculated the number needed to analyze as 435 subjects to show a 5 % proportional difference between fatal and nonfatal overdoses with 80 % power and 5 % alpha.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Figure 1 summarizes the patient screening and final study inclusion population. Selected clinical characteristics (demographics, vital signs, laboratory, past medical history, etc.) with respect to the clinician’s decision to order cTnI are outlined in Table 2. In addition to 61 patients with prior CAD, there were only 16 patients (3.6 %) with prior congestive heart failure. Abnormal vital signs (i.e., tachycardia, bradycardia, hypotension) were not substantially different in the groups with elevated cTnI or mortality. Clinicians were less likely to order cTnI in patients with positive cocaine toxicology screens; however, there were no significant difference in proportions of death or coronary artery disease between groups. The top five most common overdosed drug classes were the following: benzodiazepines (22 %), opioids (20 %), sympathomimetic (18 %), acetaminophen (18 %), and antidepressants (15 %).

Fig. 1.

Study enrollment diagram. cTnI cardiac troponin I, N number of patients

Table 2.

Selected clinical characteristics of included patients

| Clinical characteristic |

N or median (% or IQR)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| cTnI not sent | cTnI ordered | |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years)* | 38.5 (25–50) | 50.6 (41–58) |

| Male gender | 109 (58) | 280 (64) |

| Vital signs (initial ED) | ||

| Pulse (bpm)* | 97 (82–117) | 90 (77–106) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 128.5 (115–147) | 132 (120–148) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 75 (64–87) | 75 (64–86) |

| Laboratory testing | ||

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L)* | 25 (22.8–28.3) | 29 (26–32) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.8–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) |

| Toxicology screens | ||

| Cocaine positive* | 65 (34.6) | 60 (13.7) |

| Medical history | ||

| Prior CAD | 34 (18.1) | 61 (14.0) |

| Outcomes | ||

| All-cause mortality | 4 (2.1) | 20 (4.6) |

| Total | 188 | 437 |

Indicates p < 0.05 from univariate association with clinician’s decision to order cTnI as part of routine clinical care

bpm beats per minute, CAD coronary artery disease, DBP diastolic blood pressure, ED emergency department, IQR interquartile range, MAP mean arterial pressure, mEq/L milliequivalents per liter, mg/dL milligram per deciliter, mmHg millimeters of mercury, SBP systolic blood pressure

Cardiac Biomarker (cTnI) Data

The median number of cTnI tests ordered on patients was 2, with 20 patients having 3 or more cTnI tests ordered. Elevation of initial cTnI and peak cTnI occurred in 50 and 60 patients, respectively, and both were highly associated with fatality (initial OR 21.0, peak OR 25.0). Mean initial cTnI was significantly higher in fatal versus nonfatal overdoses (1.2 vs. 0.06 ng/mL, p <0.001); however, peak cTnI was not significantly higher (1.3 vs. 0.38 ng/mL, p = 0.3). The independent prognostic value of elevated initial cTnI (>0.09 ng/ml) to predict mortality was confirmed in a multivariable model that controlled for age, gender, and prior CAD (adjusted OR 25.2, 95 % CI 8.6–73.6). A sensitivity analysis was performed which excluded those with prior CAD (N = 61), and elevated initial cTnI remained an independent predictor of mortality controlling again for age and gender (adjusted OR 24.5, 95 % CI 7.9–76.2).

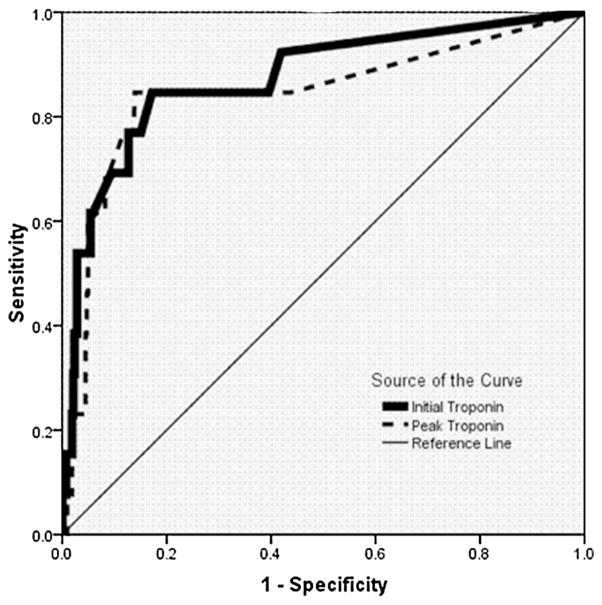

ROC Analysis

The ROC curve (Fig. 2) reveals excellent AUC for prediction of mortality using the initial cTnI (c = 0.87, CI 0.76–0.98). Utilizing the peak cTnI, instead of the initial cTnI, did not improve the AUC (c = 0.84, 0.71–0.98). Elevated initial cTnI (>0.09 ng/mL) significantly predicted mortality (OR 21.1, CI 6.2–71.4) as did peak cTnI (OR 25, CI 6.7–93.9). The optimal cTnI cutpoints along the ROC curve were an initial cTnI >0.02 ng/mL (85 % sensitive, 83 % specific) and a peak cTnI >0.05 ng/mL (85 % sensitive, 86 % specific).

Fig. 2.

ROC curves are demonstrated for initial cTnI (thick line) and peak cTnI (dashed line). ROC receiver operating characteristics

Diagnostic Test Characteristics

Test characteristics for initial cTnI (90 % specificity, 99 % negative predictive value) were better than peak cTnI (88.2 % specificity, 99.2 % negative predictive value). Initial cTnI was normal in only one death out of the entire cohort (1/437 or 0.2 %, 95 % CI 0.01–1.4). Full diagnostic test characteristics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Diagnostic test characteristics of cardiac biomarkers for drug overdose

| Biomarker | AUC | OR | Sensitivity | Specificity | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95 % CI) | (95 % CI) | (95 % CI) | (95 % CI) | (95 % CI) | |

| Initial cTnI* | 0.87 | 21.1 | 70 | 90.4 | 99.0 |

| (>0.09 ng/mL) | (0.76–0.98) | (6.2–71.4) | (39–91) | (87–93) | (97–100) |

| Peak cTnI | 0.83 | 25.0 | 77 | 88.2 | 99.2 |

| (>0.09 ng/mL) | (0.69–0.96) | (6.7–93.9) | (46–95) | (84–91) | (97–100) |

| CKMB % (Index >5) | 0.48 | 0 | 0 | 95.9 | 96.4 |

| (0.27–0.69) | – | (0–41) | (92–98) | (93–99) | |

| CK (>1000 U/L) | 0.56 | 2.3 | 22 | 89.3 | 97.7 |

| (0.35–0.76) | (0.5–11.9) | (3–59) | (85–92) | (95–99) |

Mean initial cTnI significantly associated with mortality (1.2 vs. 0.06 ng/mL, p < 0.001)

AUC area under ROC curve, CI confidence intervals, CK creatine phosphokinase, cTnI cardiac troponin I, MB myoglobin, NPV negative predictive value, OR odds ratio

Discussion

This is the largest study to demonstrate the utility of cardiac biomarkers to predict in-hospital mortality for undifferentiated patients with acute drug overdose. We found that the initial cTnI had excellent diagnostic test characteristics to predict acute drug overdose mortality. Future research should focus on high-risk overdose features to optimize strategies for utilization of cTnI as part of the evaluation of patients with acute drug overdose.

These findings are consistent with a prior study that demonstrated a strong association of ECG ischemia with adverse cardiovascular events in overdose patients [17]. In that prior study, components of the initial ECG were analyzed for the ability to predict cardiovascular events, and it was found that ECG evidence of ischemia was present in 40 % of patients who went on to have in-hospital cardiac arrest, versus 18 % of those who did not (p < 0.05). Therefore, it is not surprising that the current analysis found biomarker evidence of ischemia as predictive of mortality in a similar patient population. Future studies should combine a cardiac biomarker approach with an ECG approach for risk stratification of drug overdose patients.

We found no association between clinician’s likelihood of ordering cTnI and prior CAD. This suggests that clinicians were equally likely to order cTnI in CAD patients. Therefore, this is unlikely to have confounded our results. This may be explained by the fact that non-CAD (i.e., younger) patients represent a higher-risk age group for drug-related fatality based on historical data [18]. The death rate in patients without cTnI was only 2.1 % (4 out of 188), suggesting that the specificity and negative predictive value of cTnI would likely be improved if 100 % of the cohort had cTnI results. Ongoing studies are being performed to assess the role of CAD status in overdose risk and mortality.

Our findings raise the question regarding how clinicians should manage patients differently if they have elevated cTnI during the hospital course. Clearly, patients with elevated cTnI require telemetry monitoring and consideration of critical care unit admission. In contrast, a negative cTnI was found to exclude fatality with extremely high predictive value (>99 %). Further studies are necessary to evaluate whether initiation of certain treatments (e.g., intralipid for lipophilic exposures, hyperinsulin-euglycemia for calcium-channel blockers, etc.) should be empirically initiated for patients with elevated cTnI. Clinical trials of disposition decisions should incorporate initial cTnI in selected patients, moving forward.

Limitations

The findings in this study should be interpreted with several important considerations. This study was performed at the affiliate hospitals of one medical school in an urban catchment area; thus, these results should be externally validated in other settings in a distinct patient population. In addition, cTnI was lacking in moderate subset (30 %) of patients; however, this probably biased toward the null considering that cTnI probably would have been negative in the patients for which it was not ordered (i.e., the lowest risk overdoses). And finally, these results do not apply to excluded populations such as children or pre-hospital cardiac arrests.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that for adult ED patients with acute drug overdose, the initial cTnI result was strongly associated with in-hospital mortality. Furthermore, we found that serial cTnI did not improve upon the diagnostic test characteristics of the initial cTnI; therefore, serial cTnI is not indicated for the routine drug overdose evaluation. Future research should focus on high-risk overdose features to optimize strategies for utilization of cTnI as part of the ED evaluation for acute drug overdose.

References

- 1.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Miniño AM. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;81:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warner M, Chen L, Makuc D. NCHS Data Brief. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [Accessed 1 July 2014]. Increase in fatal poisonings involving opioid analgesics in the USA, 1999–2006. www.cdc.gov. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, McMillan N, Ford M. 2013 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 31st annual report. Clinical Toxicology (Phila) 2014;52:1032–1283. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.987397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang DH, Spyres MB, Fox L, Manini AF. Toxin-induced cardiovascular failure. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2014;32:79–102. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Flores ED, McBride W, Kim AS, Wells PJ. Potentiation of cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction by beta-adrenergic blockade. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;112:897–903. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-12-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manini AF, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. Prognostic utility of serum potassium in chronic digoxin toxicity. American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 2011;11:173–178. doi: 10.2165/11590340-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreadou I, Iliodromitis EK, Rassaf T, Schulz R, Papapetropoulos A, Ferdinandy P. The role of gasotransmitters NO, H2S, CO in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotection by preconditioning, postconditioning, and remote conditioning. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2015;172:1587–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manini AF, Nelson LS, Stimmel B, Vlahov D. Incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in adults following drug overdose. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012;19:843–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanden Hoek TL, Morrison LJ, Shuster M, Donnino M, Sinz E, Lavonas EJ. Part 12: Cardiac arrest in special situations: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122(Suppl 3):S829–S861. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaze DC, Collinson PO. Cardiac troponins as biomarkers of drug- and toxin-induced cardiac toxicity and cardiac protection. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism and Toxicology. 2005;1:715–725. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD. The writing group on behalf of the joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF task force for the universal definition of myocardial infarction: Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60(12):1581–1598. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley WE, Januzzi JL, Christenson RH. Increases of cardiac troponin in conditions other than acute coronary syndrome and heart failure. Clinical Chemistry. 2009;55:2098–2112. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.130799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanindi A, Cemri M. Troponin elevation in conditions other than acute coronary syndromes. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2011;7:597–603. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S24509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Heyningen C, Watson ID. Troponin for prediction of cardiovascular collapse in acute colchicine overdose. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2005;22:599–600. doi: 10.1136/emj.2002.004036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. [Accessed 15 Jan 2015];N.Y. Public Health Law § 2500-d. http://public.leginfo.state.ny.us.

- 16.Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Barta DC, Steiner J. Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: where are the methods? Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1996;27:305–308. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manini AF, Nelson LS, Skolnick AH, Slater W, Hoffman RS. Electrocardiographic predictors of adverse cardiovascular events in suspected poisoning. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 2010;6:106–115. doi: 10.1007/s13181-010-0074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockett IR, Hobbs G, De Leo D, Stack S, Frost JL, Ducatman AM. Suicide and unintentional poisoning mortality trends in the United States, 1987–2006: Two unrelated phenomena? BMC Public Health. 2010;10:705. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]