Abstract

Histone deacetylase 4 (Hdac4) regulates chondrocyte hypertrophy. Hdac4−/− mice are runted in size and do not survive to weaning. This phenotype is primarily due to the acceleration of onset of chondrocyte hypertrophy and, as a consequence, inappropriate endochondral mineralization. Previously, we reported that Hdac4 is a repressor of matrix metalloproteinase-13 (Mmp13) transcription, and the absence of Hdac4 leads to increased expression of MMP-13 both in vitro (osteoblastic cells) and in vivo (hypertrophic chondrocytes and trabecular osteoblasts). MMP-13 is thought to be involved in endochondral ossification and bone remodeling. To identify whether the phenotype of Hdac4−/− mice is due to up-regulation of MMP-13, we generated Hdac4/Mmp13 double knockout mice and determined the ability of deletion of MMP-13 to rescue the Hdac4−/− mouse phenotype. Mmp13−/− mice have normal body size. Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− double knockout mice are significantly heavier and larger than Hdac4−/− mice, they survive longer, and they recover the thickness of their growth plate zones. In Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− double knockout mice, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) expression and TRAP-positive osteoclasts were restored (together with an increase in Mmp9 expression) but osteocalcin (OCN) was not. Micro-CT analysis of the tibiae revealed that Hdac4−/− mice have significantly decreased cortical bone area compared with the wild type mice. In addition, the bone architectural parameter, bone porosity, was significantly decreased in Hdac4−/− mice. Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− double knockout mice recover these cortical parameters. Likewise, Hdac4−/− mice exhibit significantly increased Tb.Th and bone mineral density (BMD) while the Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice significantly recovered these parameters toward normal for this age. Taken together, our findings indicate that the phenotype seen in the Hdac4−/− mice is partially derived from elevation in MMP-13 and may be due to a bone remodeling disorder caused by overexpression of this enzyme.

Keywords: Mmp13, Hdac4, Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− double knockout, cortical bone

1. Introduction

Histone deacetylase 4 (Hdac4) is a member of the class IIa HDACs and plays a central role in the formation of the skeleton [1, 2]. Hdac4 is expressed in prehypertrophic chondrocytes, and mice with global deletion of HDAC4 are significantly smaller than wild type mice and die during the first week of life. This is mainly due to ectopic ossification of endochondral cartilage, which prevents expansion of the rib cage and leads to an inability to breathe [2]. The formation of cartilaginous templates of endochondral bones occurs normally in the Hdac4−/− mice, but the onset of chondrocyte hypertrophy is accelerated and, consequently, endochondral mineralization occurs precociously, leading to ectopic bone formation. [2].

Chondrocyte hypertrophy is the final step in chondrocyte differentiation, in which the cartilage extracellular matrix (ECM) becomes calcified and partially degraded. Ossification begins when hypertrophic chondrocytes undergo programmed cell death and the calcified cartilage is invaded by blood vessels, osteoblasts, osteoclasts and mesenchymal precursors and forms primary ossification centers. Within these centers, the hypertrophic cartilage matrix is degraded, the hypertrophic chondrocytes die, and bone replaces the disappearing cartilage. Studies have shown that chondrocyte apoptosis does not lead to endochondral ossification [3]. Angiogenesis has been implicated as a crucial step in endochondral ossification [4–6], and degradation and remodeling of the cartilage matrix is essential for vascular invasion.

Matrix metalloproteinase 13 (Mmp13, also called collagenase-3) plays an important role in the degradation of components of the cartilage ECM. MMP-13 is expressed in hypertrophic chondrocytes and osteoblasts and promotes the removal of hypertrophic cartilage from the growth plate and the remodeling of newly deposited trabecular bone during long bone development [7,8]. It degrades collagen type II efficiently but also collagens type I, III, and X, which are the major components of cartilage and bone [9]. It has been shown that MMP-13 acts directly during the initial stages of cartilage ECM degradation (the rate-limiting process for chondrocyte programmed cell death) and during angiogenesis prior to invasion by blood vessels and osteoclasts [8]. A mutation in the human Mmp-13 gene causes the Missouri variant of spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia (SEMD), a syndrome with abnormalities in development and growth of endochondral skeletal elements [10]. Mmp-13 null mice show no overt phenotypic abnormalities, they are fertile and have a normal lifespan but show abnormal growth plates and delayed ossification [7, 8]. Clinical investigation has shown that patients with articular cartilage destruction have high Mmp-13 expression [11, 12], suggesting that increased Mmp-13 may be associated with cartilage degradation. Studies have also shown that Mmp-13-overexpressing transgenic mice develop a spontaneous osteoarthritis (OA)-like articular cartilage destruction phenotype [5].

Recently, our laboratory showed that Hdac4 represses Mmp13 expression through inhibiting the activity of Runx2, and that Hdac4−/− mice displayed increased Mmp-13 mRNA and protein levels in hypertrophic chondrocytes and trabecular bone [13]. In the present study, we generated double knockout mice (Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/−) to determine whether the elevation of MMP-13 contributes to the phenotype of Hdac4−/− mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Breeding pairs of heterozygous Hdac4 mice (Hdac4+/−) on a C57BL/6 background were generated as described [1]. These heterozygous mice have no phenotypic abnormalities as described previously in [2]. Heterozygous or homozygous Mmp13-deficient mice (Mmp13−/−) mice on a C57BL/6 background were a kind gift of Dr. Jeanine D’Armiento (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York). We characterized 5 and 8-day-old male and female mice, wild type, Hdac4−/−, Mmp-13−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/−. All mice were housed under standard conditions with a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle and free access to water and chow. All the experiments using mice were performed following protocols approved by NYU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.2 Histological Analysis

Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin at 4°C overnight The samples were then decalcified in 10% EDTA. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded femurs and tibiae were cut as 8 μm sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. TRAP staining was performed using the Acid Phosphatase Leukocyte kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) following the manufacturer’s protocol after deparaffinization and acetate buffer washing. Immunohistochemical analysis of markers for bone formation, alkaline phosphatase, ALP (Abcam) and osteocalcin (Abcam), and a marker of hypertrophic chondrocytes, Type X collagen (COSMO BIO Co., LTD) were carried out with similar sections. Briefly, deparaffinized and hydrated sections were incubated with Proteinase K Solution (20 μg/ml in TE Buffer, pH 8.0) for 15 minutes in a water bath at 37°C. After cooling, the sections were rinsed with PBS, the endogenous peroxidase was removed by incubating sections for 15 minutes at room temperature in 3% H2O2 in methanol. After rinsing sections in a BSA solution (3% in PBS), blocking for 1 hour at room temperature (BSA solution containing 1% Triton and 5% FBS) was performed. Primary antibody diluted in PBS with 3% BSA (ALP 1:50, osteocalcin 1:100, α1(X) collagen 1:100) was incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidifying chamber. After three washes in PBS-BSA solution, secondary goat anti-rabbit peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was incubated with the sections for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were developed using Fast 3′3′-Diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich), prepared following the manufacturer’s protocol and, after washing with PBS, counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 minute. Slides were mounted using Permount mounting medium (Thermo Scientific). The staining of surface osteoclasts was quantified using BIOQUANT OSTEO 2015.

2.3 Micro-computed tomography (μCT)

The tibiae and femurs of all four genotypes and pooled sexes (8 day old mice) were fixed in 70% ethanol and prepared for high-resolution μCT (SkyScan 1172). Images were obtained using the following parameters: 40 Kv, 250 uA, pixel size of 8.5 microns, 2000×1332 matrix, 6 averages and a 0.5 mm aluminum filter. Images were reconstructed using a thresholding of 0–0.09, beam hardening correction of 35, ring artefact correction of 7, and Gaussian smoothing (factor=1). From the reconstructed micro-CT images, a 200 micron volume correlating to 25 slices of the mid-diaphysis that began immediately distal to the third trochanter was examined for total cortical cross-sectional bone area (T.Ar), cross- sectional marrow area (Ma.Ar), cortical bone (tissue) area (B.Ar), polar moment of inertia (MMI) and cortical thickness (Ct.Th). Relative cortical area (RCA) was defined as B.Ar/T.Ar and represented the relative amount of bone tissue in a given bone area. From the reconstructed images of the distal metaphysis, a volume of 637 micron immediately proximal to the growth plate was examined for trabecular bone mineral density (BMD), bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp). BMD was calculated as the ratio of bone mineral content (BMC, mg) to the total volume of distal metaphysis analyzed after removing (masking) marrow space grayscale variability.

2.4 Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was obtained from femurs and tibiae using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 0.1 μg of total RNA using a TaqMan reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) with hexamer primers following the protocol described by the manufacturers. Gene expression levels were measured using SYBR Green PCR Reagent (Applied Biosystems). Primer pairs used for quantitative detection of gene expression are listed in Table 1. The quantity of mRNA was calculated by normalizing the Ct (threshold cycle value) of specific genes to the Ct of the housekeeping gene β-actin.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences for real-time RT-PCR

| Gene | Primers (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Mouse α1(X) | Forward, TCATGCCTGATGGCTTCATA Reverse, GCACCTACTGCTGGGTAAGC |

| Mouse ALP | Forward, ATCTTTGGTCTGGCTCCCATG Reverse, TTTCCCGTTCACCGTCCAC |

| Mouse OCN | Forward, GCAATAAGGTAGTGAACAGAC Reverse, GTTTGTAGGCGGTCTTCAAGC |

| Mouse TRAP | Forward, CACTCCCACCCTGAGATTTGTG Reverse, ACGGTTCTGGCGATCTCTTTG |

| Mouse Mmp-9 | Forward, CGCTCATGTACCCGCTGTAT Reverse, CCGTGGGAGGTATAGTGGGA |

| Mouse Mmp-2 | Forward, GCCCCCATGAAGCCTTGTTT Reverse, GGTCATAGTCCTCGGTGGTG |

| Mouse Mef2c | Forward, CTTCTGCCACTGGCCCAC Reverse, GGGGTTGCCGTATCCATTC |

| Mouse Mef2c | Forward, CCCAGCCACCTTTACCTACA Reverse, TATGGAGTGCTGCTGGT |

| Mouse b-Actin | Forward, TCCTCCTGAGCGCAAGTACTCT Reverse, CGGACTCATCGTACTCCTGC |

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical differences were determined using Student’s t test for survival data of comparison between Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− mice. Other mean differences were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using IBM SPSS (v22, Armonk, NY). Results are expressed as mean ± SE and a p < 0.05 was considered significant comparing each of the groups.

3. Results

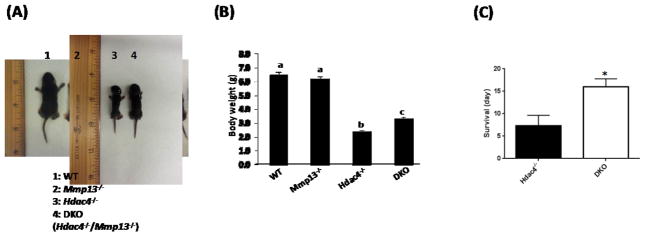

3.1 Mmp13 ablation in HDAC4−/− mice increased their body weight, length and survival rate

To investigate the contribution of MMP-13 elevation to the premature phenotype seen in the Hdac4−/− mice, we generated double knockout mice (Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/−). Hdac4−/− mice were severely runted (Fig. 1A, B) and died during the first week of life (Fig. 1C). Mmp13−/− mice showed no gross phenotypic abnormalities (Fig. 1A), were fertile and had a normal lifespan. The Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− double knockout mice were bigger, heavier, and survived longer when compared with Hdac4−/− mice (Fig. 1). These results indicate that Hdac4−/− mice lacking Mmp13 exhibit partial recovery of their phenotype.

Fig. 1. Images, body weights and survival of Hdac4−/− mice compared with Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/−.

A, Postnatal day 8 (P8) wild type (WT, n=12), Mmp-13 knockout (Mmp-13−/−, n=15), Hdac4 knockout (Hdac4−/−, n=17) and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− (DKO, n=11) male mice are shown. B, Body weights of male and female genotypes. Data shown are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate p<0.05 vs. one another. C, Survival of Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− (DKO) male and female mice. *p<0.05 vs. Hdac4−/−.

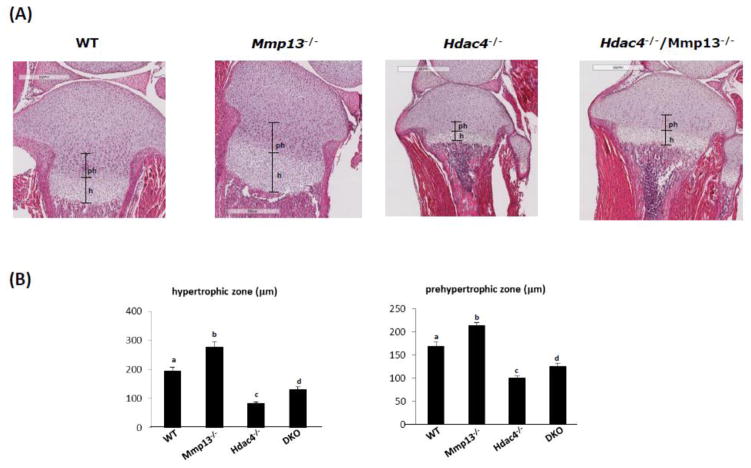

3.2. Mmp13 ablation in HDAC4−/− mice partially restored the skeletal cellularity phenotype of Hdac4−/− mice

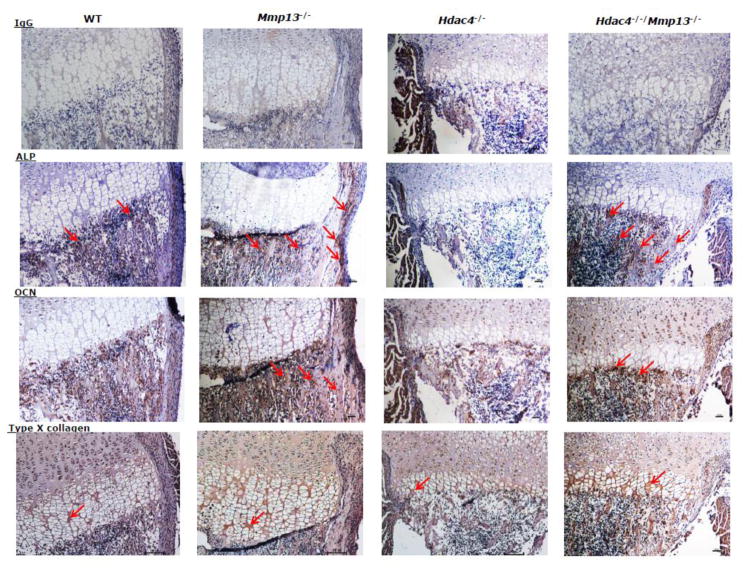

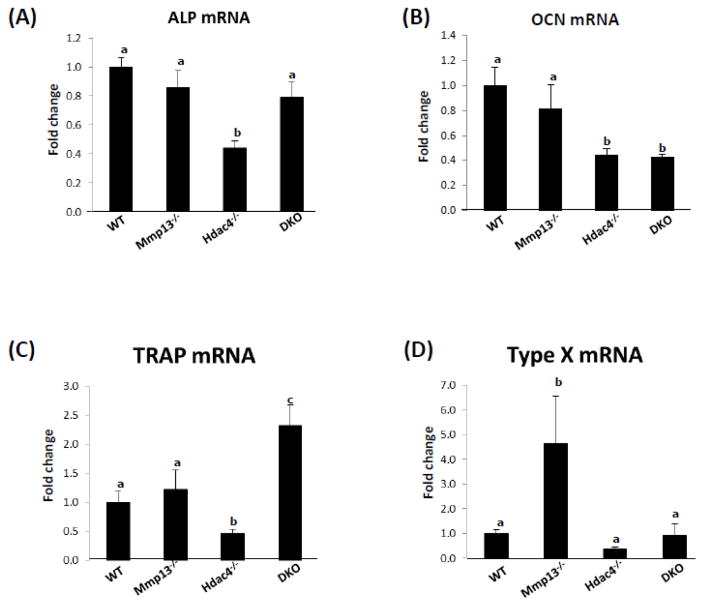

Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on sections of tibiae isolated from wild type, Mmp13−/−, Hdac4−/−, and Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− male mice at P8. Overall the histological sections showed that Hdac4−/− mice have malformed bones with extremely shortened growth plates. On the other hand, Mmp13−/− mice showed a lengthened prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocyte zone. Ablation of Mmp13 in the Hdac4−/− mice partially but significantly recovered the thickness of both the hypertrophic and prehypertrophic chondrocyte zones, as well as the morphology of the cartilaginous zone (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, the bones of the Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice were still abnormal. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis revealed that ALP and osteocalcin (OCN) expression levels, as early and late osteoblastic markers, respectively, were decreased in Hdac4−/− mice compared with wild type mice, whereas in comparison with Hdac4−/− mice, ALP expression was increased in the Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice (Fig. 3). In the Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, the expression of ALP mRNA was significantly recovered from the reduced levels seen in the Hdac4−/− mice. But OCN did not recover (Fig. 4A, B). IHC showed that the expression of type X collagen (COL10A1), a marker of hypertrophic chondrocytes, was increased in Mmp-13−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice compared with wild type mice (Fig. 3). In comparison with wild type mice, type X collagen mRNA was very highly increased in Mmp13−/− mice (Fig. 4D). Next, we determined if other MMP molecules might compensate for Mmp-13 in Mmp-13−/− or Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice. Indeed Mmp-9 showed higher mRNA levels in the Mmp-13−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, while Mmp-2 was unchanged (Fig. 5A, B). Runx2 expression was unchanged but, interestingly, Mef2c levels were increased in Hdac4−/− mice and returned to the same levels as wild type in the double knockout mice. Indeed, these results suggest that Mmp-13 may be a regulator of Mmp-9 and Mef2c expression (Fig. 5C, D).

Fig. 2. Histological examination of all four genotypes.

A, Hematoxylin and eosin stained tibiae at postnatal day 8 (P8) WT, Mmp-13−/−, Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− male mice. 4x. B, Morphometric analysis of the length of the prehypertrophic (ph), and hypertrophic (h) zones in P8 WT (n=3), Mmp-13−/− (n=5), Hdac4−/− (n=6) and DKO (n=5) female and male mice. Data shown are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate p<0.05 vs. one another. The images were quantified using Image J software.

Fig. 3. Immunohistochemistry of all four genotypes.

Tibiae from female mice of postnatal day 8 (P8) WT (n=2), Mmp-13−/− (n=3), Hdac4−/− (n=4)and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− (n=3)were used. 10x

Fig. 4. Gene expression of all four genotypes.

Total RNA was extracted from distal femurs of 5-day postnatal male and female WT (n=6), Mmp-13−/− (n=6), Hdac4−/− (n=5), and DKO mice (n=4). RNAs were measured using real time RT-PCR. The relative levels of mRNAs were normalized to β-actin. Data are shown as –fold change to WT. Data shown are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate p<0.05 vs. one another.

Fig. 5. Gene expression of all four genotypes.

Total RNA was extracted from distal femurs of 5-day postnatal male and female WT (n=6), Mmp-13−/− (n=6), Hdac4−/− (n=5), and DKO mice (n=4). RNAs were measured using real time RT-PCR. The relative levels of mRNAs were normalized to β-actin. Data are shown as –fold change to WT. Data shown are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate p<0.05 vs. one another.

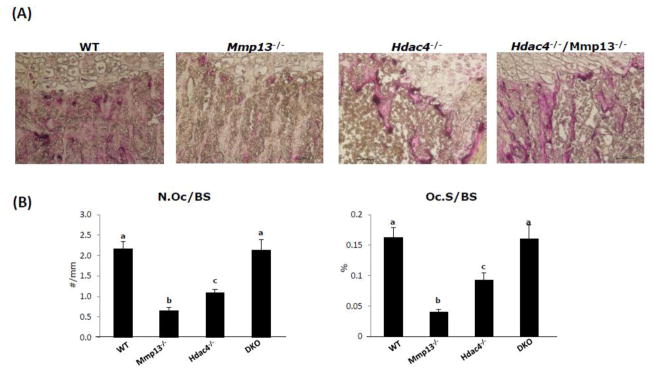

The surface osteoclasts, determined by TRAP staining, a marker of differentiated osteoclasts, was significantly decreased in Mmp-13−/− mice and slightly decreased in Hdac4−/− mice compared with wild type mice. In the Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, the TRAP positive osteoclasts returned to the same levels as wild type mice (Fig. 6A), indicating a return to relatively normal bone remodeling. In line with these observations, TRAP mRNA abundance was up-regulated in the Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− mice compared with Hdac4−/− mice (Fig. 4C). Taken together these results indicate that MMP-13 in the Hdac4−/− mice influences bone formation, especially early stages of osteoblast differentiation, and osteoclast recruitment and differentiation.

Fig. 6. TRAP staining of all four genotypes.

A, Tibiae of postnatal day 8 (P8) WT, Mmp-13−/−, Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− female mice are shown. 20x. B, Quantification of osteoclast number in postnatal day 8 (P8) WT, Mmp-13−/−, Hdac4−/−, and DKO mice. Data shown are mean ± SE. Different letters indicate p<0.05 vs. one another, n = 4 in each group.

3.3 Hdac4−/− mice have structurally modified cortical and trabecular bone which was partially restored by deletion of Mmp13

Micro-CT analysis of cortical and trabecular areas of the tibiae of male and female P8 mice revealed that Hdac4−/− mice had significant decreases in almost all cortical parameters, including bone length (Fig. 8, 9). The Hdac4−/− mice had a diminution in porosity and polar moment of inertia (MMI; the index of difficulty to bend), suggesting increased bone rigidity compared with wild type mice. Ablation of Mmp13 in Hdac4−/− mice led to an increase in T.Ar and concomitant increase in M.Ar, but no changes in B.Ar, and significantly recovered porosity. Robustness (T.Ar/Length) increased in the Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, reflecting the increase in total area. Lack of Mmp13 in Hdac4−/− mice partially normalized radial bone growth. Mmp-13−/− mice were largely similar to wild type, except for lower cortical thickness and length and greater porosity.

Fig. 8. Hdac4−/− mice have decreased cortical bone area and structure which were restored in Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− mice.

Tibiae from male and female mice of postnatal day 8 (P8) WT, Mmp-13−/−, Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− were used. Different letters indicate p<0.05 vs. one another, n = 7–8 in each group.

Fig. 9. The trabecular thickness, BMD, and bone surface were normalized in Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− mice.

Tibiae from mice at postnatal day 8 (P8) of WT, Mmp-13−/−, Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− were used. Different letters indicate p<0.05 vs. one another, n = 7–8 in each group.

The trabecular bone compartment was assessed for ~ 600 μm below the proximal growth plate of the tibiae. Hdac4−/− mice show reduced BV/TV, however their trabeculae are thicker, likely due to decreased resorption. Trabecular bone shows differences in structural parameters: ablation of Hdac4 induced increases in Tb.Th. and BMD. With the deletion of Mmp13 in Hdac4−/− mice, these parameters normalized. The degree of anisotropy (DA), reflecting trabecular structure, decreased in Hdac4−/− mice, suggesting more isotropic (organized) bone compared to wild type mice but this was not affected by Mmp-13. In the Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, Tb.Sp. was unchanged compared to Hdac4−/− mice; perhaps influenced by an increase in the marrow area (area inside the endosteal perimeter). Taken together, although Tb.Sp. and DA were not changed, the Tb.Th. and BMD were normalized with deletion of Mmp13 in Hdac4−/− mice. Bone surface density (BS/BV) is a useful parameter to characterize the complexity of trabecular structure. Lower BS/BV in Hdac4−/− mice suggests more membranous bone than the other genotypes (wild type, Mmp13−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice). The micro-CT images of Hdac4−/− mice (Fig. 7) show that the surface of the cortical bone of these mice is smoother than the wild type and Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, suggesting that Hdac4−/− mice had more mature (mineralized) bone than wild type mice. Taken together, our data indicate that increases in MMP-13 in Hdac4−/− mice affect cortical bone area and architecture and trabecular bone mineral density and thickness.

Fig. 7. Bone images obtained by μCT analysis.

Tibiae from mice at postnatal day 8 (P8) of WT, Mmp-13−/−, Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− were used. n = 7–8 in each group

4. Discussion

Our initial goal was to determine whether elevations in MMP-13 in Hdac4−/− mice contribute to their skeletal phenotype. To that end, we generated Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− double knockout mice. Hdac4−/− mice display dwarfism and do not survive to weaning. In the present paper, we show that Hdac4−/− mice lacking Mmp13 have improved body weight, length and survival. In our previous study we showed that Hdac4 ablation in mice resulted in increased Mmp-13 expression and protein levels in vivo. Heterozygous Hdac4 mice (Hdac4+/−) were normal and did not display increased Mmp-13 levels [13]. Previous studies have shown that Hdac4−/− mice show impaired chondrocyte hypertrophy leading to ectopic bone formation [2]. On the other hand, Mmp13−/− mice display terminally differentiated chondrocytes accumulating in the pre-hypertrophic zone and delayed chondrocyte apoptosis [8] leading to an increase in the height of the hypertrophic zone without changes in overall bone length.

Osteoblast differentiation in vitro and in vivo can be characterized in three stages: cell proliferation, matrix maturation, and matrix mineralization [14]. The matrix maturation phase is characterized by maximal expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP). At the beginning of matrix mineralization, the osteocalcin (OCN) gene is expressed. We showed that in Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, the expression of ALP mRNA and protein recovered from the reduced levels seen in Hdac4−/− mice, suggesting that MMP-13 affects the early stage of osteoblast differentiation. MMP-13 is synthesized by osteoblasts and osteocytes in bone, and hypertrophic chondrocytes in cartilage [15, 16, 17]. An MMP-13 endocytotic-receptor system was identified in osteoblastic cells and chondrocytes [18, 19], and it was shown that extracellular MMP-13 causes activation of ERK1/2 in rabbit chondrocytes [20]. Although there is a possibility that MMP-13 may regulate ALP expression through this receptor system, the mechanism is not clear.

Mmp13−/− mice exhibit significant reductions in the number of activated osteoclasts [21 and Fig. 5]. In contrast, overexpression of MMP-13 resulted in the formation of osteoclasts that were larger in size and displayed a greater resorption capacity [22]. The role of MMP-13 in osteoclastogenesis could be explained as a synergistic effect with MMP-9 [8, 23]. MMP-13 indirectly induces osteoclast differentiation by activating pro-MMP-9, which is known to induce recruitment of osteoclasts, and cleave galectin-3 in a MMP-9-dependent or independent manner, thus blocking its inhibitory effect on osteoclastogenesis [16]. MMP-9 is highly expressed in monocytes (osteoclast precursors) and multinucleated osteoclasts that resorb bone. MMP-9 is not a collagenase, however, the results of this study reveal that MMP-9 may compensate in Mmp-13 null mice. Our data with TRAP staining in Mmp13−/− mice showing decreases in osteoclast surface are consistent with previous results. The Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− double knockout mice partially restored the reduction of osteoclast surface in Hdac4−/− mice. Hdac4−/− mice die at approximately 8 days of age (average 7.3 ± 2.3 days). Nonetheless, based on the H&E staining, it appears that almost all chondrocytes of the growth plate proceed to ossification. Thus, in Hdac4−/− mice, the ossification rate is accelerated, so the epiphyses are much smaller. The lack of MMP-13 in Hdac4−/− mice appears to have partially restored the ossification and epiphyseal morphology.

Our micro-CT analyses showed that Hdac4−/− mice have significantly reduced cortical bone area compared with wild type mice. Elevation in MMP-13 appears to contribute to decreased radial rather than longitudinal growth in Hdac4−/− mice. Thus, we assume that in Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, bones become wider through periosteal bone apposition [24]. On the other hand, endosteal resorption excavates the marrow cavity [25]. The balance between periosteal bone apposition and endosteal bone resorption is important for advancing overall bone growth. In Hdac4−/− mice, it is possible that earlier completion of longitudinal growth and earlier inhibition of periosteal apposition produces a smaller bone. Lack of MMP-13 in Hdac4−/− mice appears to partially reverse the inhibition of periosteal bone apposition. It is reported that net endosteal apposition contributes to the final cortical thickness [26, 27]. Since cortical thickness and RCA (B.Ar/T.Ar) are similar in both Hdac4−/− and Hdac4−/−/Mmp-13−/− mice, endosteal resorption may increase in proportion to increase in periosteal apposition. The Hdac4−/− mice appear to have more compressed and easily broken cortical bone as suggested by lower cortical bone porosity and MMI, respectively, and these architectural parameters tended to recover in the Hdac4−/− mice lacking MMP-13. These results indicate that increases in MMP-13 in Hdac4−/− mice affect cortical bone mass and architecture but not length. In conclusion, the premature phenotype seen in Hdac4−/− mice is partially derived from MMP-13 elevation and may be due to a bone turnover disorder that influences the whole tibial cortical bone area, trabecular thickness, and BMD. Even though the length of growth plate zones was partially recovered in Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice, they may not be able to recover the whole bone length. Although Mmp-13 and Mmp-9 are direct targets of Runx2 in bone tissue [28–32] we did not find any effect of deletion of Mmp-13 or Hdac4 on Runx2 gene expression. Interestingly, Mef2c expression level was increased in Hdac4−/− mice and normalized in Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice. This suggests that Mef2c gene expression is inhibited by HDAC4 and removal of MMP-13 with partial restoration of the bone phenotype in some way leads to normalization of Mef2c. It also suggests that the elevated Mef2c may have some influence on the premature phenotype seen in Hdac4−/− mice. Mef2c, a MADS (MCM1, Agamous, Deficiens, serum response factor) box factor, was for some time considered only important for regulating muscle and cardiovascular function. In 2007, Amood et al. demonstrated that Mef2c is a necessary early regulator of endochondral bone development and deletion of one Mef2c allele in Hdac4−/− mice normalized ossification of the chondrocostal cartilage and sternum. Ossification of endochondral cartilage depends on the balance between transcriptional activity by Mef2c and repression by HDAC4 [33]. Recently, it has been reported that Mef2c binds to the SOST enhancer and it is necessary for transcriptional activation of Sost [34, 35]. Sclerostin (encoded by the SOST gene) is expressed primarily by osteocytes in vivo [36, 37] and is an inhibitor of the Wnt anabolic pathway for bone formation. Osteoblast or late osteoblast/early osteocyte inactivation of Mef2c results in increased bone mass [35, 38]. We examined whether Sost gene expression is up-regulated in Hdac4−/− mice, but found it was not changed (data not shown). Kramer et al. revealed that the phenotype seen in late osteoblast/early osteocyte inactivation of Mef2c is primarily by a reduction in osteoclast activation (through other mechanisms than reduction of Sost gene expression). Mef2c may play an important role in the premature phenotype seen in the Hdac4−/− mice but the mechanism of how HDAC4 and MMP-13 regulate Mef2c expression and whether and if so, how Mef2c participates in the phenotype that is seen in Hdac4−/− mice, is unclear. The Hdac4−/−/Mmp13−/− mice still have an abnormal phenotype, suggesting the contribution of other factor(s) to the phenotype of Hdac4−/− mice and more investigation is needed to completely understand the mechanisms.

Highlights.

We generated Hdac4/Mmp13 double knockout mice and determined the ability of deletion of MMP-13 to rescue the Hdac4−/− mouse phenotype.

Hdac4−/− mice lacking Mmp13 exhibit partial recovery of the premature phenotype.

MMP-13 in the Hdac4−/− mice influences ALP, Mmp9 and TRAP expression.

Increases in MMP-13 in Hdac4−/− mice affect cortical bone area and architecture and trabecular bone mineral density and thickness.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Eric Olson and Dr. Jeanine D’Armiento for kindly giving us heterozygous Hdac4 deficient mice (Hdac4+/−), and heterozygous or homozygous Mmp13-deficient mice (Mmp13−/−) mice on a C57BL/6 background, respectively. We thank Dr. Malvin Janal for advice on statistical analyses. This work was funded by an NIH grant to N.C.P (DK47420). The microCT was funded by NIH grant OD010751 (to N.C.P.).

Abbreviations

- TRAP

tartrate-acid resistant acid phosphatase

- Runx2

Runt-related transcription factor 2

- Mmp13

matrix metalloproteinase-13

- Hdac4

histone deacetylase 4

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vega RB, Matsuda K, Oh J, Barbosa AC, Yang X, Meadow E, McAnally J, Pomajzl C, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Karsenty G, Olson EN. Histone deacetylase 4 controls chondrocyte hypertrophy during skeletogenesis. Cell. 2004;119:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colnot CI, Helms JA. A molecular analysis of matrix remodeling and angiogenesis during long bone development. Mech Develop. 2001;100:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maes C, Carmeliet P, Moermans K, Stockmans I, Smert N, Collen D, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G. Impaired angiogenesis and endochondral bone formation in mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms VEGF164 and VEGF188. Mech. Develop. 2002;111:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zelzer E, Mamluck R, Ferrara N, Johnson RS, Schipani E, Olson BR. VEGFA is necessary for chondrocyte survival during bone development. Development and disease. 2004;131:2161–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.01053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, Berger JE, Helms JA, Hanahan D, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Werb Z. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inada M, Wang Y, Byrne MH, Rahman MU, Miyaura C, López-Otín C, Krane SM. Critical roles for collagenase-3 (Mmp13) in development of growth plate cartilage and in endochondral ossification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17192–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407788101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stickens D, Behonick DJ, Ortega N, Heyer B, Hartenstein B, Yu Y, Fosang AJ, Schorpp-Kistner M, Angel P, Werb Z. Altered endochondral bone development in matrix metalloproteinase 13-deficient mice. Development. 2004;131:5883–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.01461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behonick DJ, Xing Z, Lieu S, Buckley JM, Lot JC, Marcucio RS, Werb Z, Miclau T, Colnot C. Role of matrix metalloproteinase 13 in both endochondral and intramembranous ossification during skeletal regeneration. PLoS One. 2007;11:e1150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy AM, Inada M, Krane SM, Christie PT, Harding B, López-Otín C, Sánche LM, Pannett AAJ, Dearlove A, Hartley C, Byrne MH, Reed AAC, Nesbit MA, Whyte MP, Thakker RV. MMP13 mutation causes spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia, Missouri type (SEMDMO) J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2832–2842. doi: 10.1172/JCI22900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bau B, Gebhard PM, Haag J, Knorr T, Bartnik E, Aigne T. Relative messenger RNA expression profiling of collagenase and aggrecanases in human articular chondrocytes in vivo and in vitro. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2648–2657. doi: 10.1002/art.10531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aigner T, Zien A, Hanisch D, Zimmer R. Gene expression in chondrocytes assessed with use of microassays. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85:117–123. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300002-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu E, Selvamurugan N, Westendorf J, Olson EN, Partridge NC. HDAC4 represses matrix metalloproteinase-13 transcription in osteoblastic cells, and parathyroid hormone controls this repression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9616–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein GS, Lian JB. Molecular mechanisms mediating developmental and hormone-regulated expression of genes in osteoblasts: an integrated relationship of cell growth and differentiation. In: Noda M, editor. Cellular and molecular biology of bone. Tokyo: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 47–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Alonzo RC, Selvamurugan N, Krane SM, Partridge NC. Bone proteinases. In: Bilizekian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan GA, editors. Principles of Bone Biology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc; 2002. pp. 251–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borden P, Soymar D, Sucharczuk A, Lindman B, Cannon P, Heller RA. Cytokine control of interstitial collagenase and collagenase-3 gene expression in human chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23577–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reboul P, Pelletier JP, Tardif G, Cloutier JM, Martel-Pelletier J. The new collagenase, collagenase-3, is expressed and synthesized by human chondrocytes but not by synoviocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2011–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI118636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barmina OY, Walling HW, Fiacco GJ, Freije JMP, Lopez-Otin C, Jeffrey J, Partridge NC. Collagenase-3 binds to a specific receptor and requires the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein for internalization. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30087–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walling HW, Raggatt LJ, Irvine DW, Barmina OY, Toledano JE, Goldring MB, Hruska KA, Adkisson HD, Burdge RE, Gatt CJ, Harwood DA, Partridge NC. Impairment of the collagenase-3 endocytotic receptor system in cells from patients with osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2003;11:854–63. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raggatt LJ, Jefcoat SC, Jr, Choudhury I, Williams S, Tiku M, Partridge NC. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 influences ERK signaling in articular rabbit chondrocytes. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2006;14:680–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nannuru KC, Futakuchi M, Varney ML, Vincent TM, Marcusson EG, Singh RK. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 regulates mammary tumor-induced osteolysis by activating MMP9 and TGFβ signaling at the tumor-bone interface. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3494–3504. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pivetta E, Scapolan M, Pecolo M, Wassermann B, Abu-Rumeileh I, Balestreri L, Borsatti E, Tripodo C, Colombatti A, Spessotto P. MMP-13 stimulates osteoclast differentiation and activation in tumour breast bone metastases. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R105. doi: 10.1186/bcr3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosakai N, Takaishi H, Kamekura S, Kimura T, Okada Y, Minqui L, Amizuka N, Chung U, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H, Toyama Y, D’Armiento J. Impaired bone fracture healing in matrix metalloproteinase-13 deficient mice. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2006;354:846–851. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baron R. General principles of bone biology. In: Favus MJ, editor. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 5. American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; Washington DC; USA: 2003. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seeman E. Bone quality: the material and structural basis of bone strength. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0793-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duan Y, Wang XF, Evans A, Seeman E. Structural and biomechanical basis of racial and sex differences in vertebral fragility in Chinese and Caucasians. Bone (NY) 2005;36:987–998. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang XF, Duan Y, Beck T, Seeman ER. Varying contributions of growth and ageing to racial and sex differences in femoral neck structure and strength in old age. Bone (NY) 2005;36:978–986. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jimenez MJG, Balbin M, Lopez JM, Alvarez J, Komori T, Lopez-Otin C. Collagenase 3 is a target of Cbfa1, a transcription factor of the runt gene family involved in bone formation. Mol Cell Biology. 1999:4431–442. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess J, Porte D, Munz C, Angel P. AP-1 and Cbfa/Runt physically interact and regulate PTH-dependent MMP13 expression in osteoblasts through a new OSE2/AP-1 composite element. J Biol Chem. 2001:20029–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porte D, Tuckermann J, Becker M, Baumann B, Teurich S, Higgins T, Owen MJ, Schorpp-Kistner M, Angel P. Both AP-1 and Cbfa1-like factors are required for the induction of interstitial collagenase by parathyroid hormone. Oncogene. 1999;18:667–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selvamurugan N, Partridge NC. Constitutive expression and regulation of collagenase-3 in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;3:218–23. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2000.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pratap J, Javed A, Languino LR, Wijinen AJ, van Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. The Runx2 osteogenic transcription factor regulates matrix metalloproteinase 9 in bone metastatic cancer cells and controls cell invasion. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8581–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8581-8591.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnold M, Kim Y, Czubryt MP, Phan D, AcAnally J, Qi X, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. MEF2C transcription factor controls chondrocyte hypertrophy and bone development. Develop Cell. 2007;12:377–89. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leupon O, Kramer I, Collette NM, Loots GG, Natt F, Kneissel M, keller H. Control of the SOST bone enhancer by PTH using MEF2 transcription factors. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22:1957–67. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collette NM, Genetos DC, Economides AN, Xie L, Shahnazari M, Yao W, Lane NE, Harland RM, Loots GG. Targeted deletion of Sost distal enhancer increases bone formation and bone mass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:14092–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207188109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poole KE, van Bezooijen RL, Loveridge N, Hamersma H, Papapoulos SE, Löwik CW, Reeve J. Sclerostin is a delayed secreted product of osteocytes that inhibits bone formation. FASEB J. 2005;19:1842–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4221fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robling AG, Bellido T, Turner CH. Mechanical stimulation in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of sclerostin. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6:354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer I, Baertschi S, Halleux C, Keller H, Kneissel M. Mef2c deletion in osteocytes results in increased bone mass. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27:360–73. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]