Abstract

Background

Many young, South African men use alcohol and drugs and have multiple partners, but avoid health care settings – the primary site for delivery of HIV intervention activities.

Objectives

To identify the feasibility of engaging men in HIV testing and reducing substance use with soccer and vocational training programs.

Methods

In two Cape Town neighborhoods, all unemployed men aged 18–25 years were recruited and randomized by neighborhood to: 1) an immediate intervention condition with access to a soccer program, random rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) for alcohol and drug use, and an opportunity to enter a vocational training program (n=72); or 2) a delayed control condition (n=70). Young men were assessed at baseline and six months later by an independent team.

Results

Almost all young men in the two neighborhoods participated (98%); 85% attended at least one practice (M = 42.3, SD= 34.4); 71% typically attended practice. Access to job training was provided to the 35 young men with the most on-time arrivals at practice, drug-free RDT, and no red cards for violence. The percentage of young men agreeing to complete RDT at soccer increased significantly over time; RDTs with evidence of alcohol and drug use decreased over time. At the pre-post assessments, the frequency of substance use decreased; and employment and income increased in the immediate condition compared to the delayed condition. HIV testing rates, health care contacts, sexual behaviors, HIV knowledge, condom use and attitudes towards women were similar over time.

Discussion

Alternative engagement strategies are critical pathways to prevent HIV among young men. This feasibility study shows that soccer and job training offer such an alternative, and suggest that a more robust evaluation of this intervention strategy be pursued.

Keywords: HIV Prevention, Drug Abuse, Vocational Training, Soccer, Young Men

INTRODUCTION

Young men in low and middle income countries (LMIC) are at substantial risk for HIV, substance abuse, and lifelong unemployment [1, 2]. This pattern is reflected in South Africa, despite large investments in HIV prevention and treatment [3, 4], as well as creation of a national vocational training program (SETA, Skills Education Training Authorities) [5]. Young men under-utilize medical care, HIV testing and treatment programs [6–8], as well as vocational training programs [2]. This study aims to evaluate the feasibility of soccer and vocational training as intervention delivery strategies to increase the uptake of both HIV testing and reductions in substance use and abuse by young South African men.

South Africa has 2.4 million HIV-infected men, as well as the highest number of seropositive persons of any nation [4]. HIV incidence in South Africa has been 3% for several years [3], with about 25.7% of black African men aged 25–49 years infected with HIV [4]. Most men (68%) report unprotected sex, typically with three partners in the last three months [9, 10]. More than half do not use condoms with casual partners [11]. The use of alcohol, methamphetamine (tik) and marijuana (dagga) are common among young men [12–14]. Among alcohol abusers, men are typically poly substance users [15] and also have multiple sexual partners [16].

In Cape Town, there are few prosocial activities for young men: 50% drop out of high school; more than 60% of young people are unemployed; and 25% face lifetime unemployment [17–19]. When activities such as job training are available, the services are underutilized: less than 0.9% of enrollees in SETA receive on-the-job training, and 60% are unemployed at the program’s completion [20]. SETA repeatedly has unspent training funds, as the burden is high to complete applications and progress reports. Young men need new pathways to escape the intersecting epidemics of HIV, alcohol, drug abuse, and unemployment, as well as a way to efficiently access vocational training.

With the success of combination prevention strategies, almost all HIV interventions are based in medical settings [21, 22]. Young men historically and universally underutilize medical care [23]. Most existing behavioral evidence-based interventions (EBI) for HIV are based on counseling models and are consistent with women’s “tend and befriend” coping styles, rather than men’s “fight-flight” styles [24, 25]. The developmental and societal challenges facing young men have not been the focus of EBI [25–27]. Men are more likely to engage peers when engaged in parallel activities (e.g., watching sports), rather than in (what they experience as) stigmatizing counseling settings [28, 29]. Novel, structural, community-level programs are needed that are highly desirable to men and address their HIV and substance abuse acts and create a path to engage in combination prevention [30–32]. Yet, many existing structural interventions that improve economic and health outcomes often exclude men [33, 34]. For example, microfinance [33–36], and conditional cash transfers [37–39] typically focus on women, even though men have been shown to use rewards for the benefit of their families [40–43].

Therefore, to address the challenges young men face, we designed four innovations. First, we used soccer as a strategy to engage young men, as well as to teach young men habits of daily living. Sports are naturally rewarding activities (release endorphins) and garner substantial peer and community support [44]. Sports are associated with strong feelings of masculine identity [45] and soccer is the most popular sport throughout Africa [46]. By offering soccer to all young men in a geographic neighborhood, soccer can be a structural intervention that can encourage physical activity and potentially reshape community and personal norms towards health [47, 48]. We used soccer to set a daily code of conduct: show up on time and drug and alcohol free.

Our second innovation was to ensure that a daily conduct of code was enforced. Being drug free was essential for good play. Point-of-contact rapid drug testing (RDT) for alcohol and drugs was administered randomly at the start of soccer games to ensure that men were adhering to the code of conduct. Points were recorded for arriving on time, completing a RDT for alcohol and drug use, and having no red penalty cards while playing – given for a violent act on the field. We rewarded these desirable social behaviors by providing access into vocational training to the 35 men with the most points. Both random rewards (going to a weekend soccer tournament) and a point system to earn mobile phone time were used to promote these prosocial and healthy behaviors.

Our third innovation was job training. We had successfully implemented a job training program for young people in Uganda by providing internships with artisans [49]. Two years after the intervention, 80% of the young people (i.e., 100% of those we could successfully track) were producing income monthly. However, the intervention for the Ugandan youth was delivered at a residential youth program. Residential placement or vocational training could be responsible for the reduced drug use, sex, and violence. In South Africa, we proposed soccer to be the strategy to encourage the habits critical for securing and retaining jobs. When young men adhered to the code of conduct, they earned access to job training at a local college. We hypothesized that soccer and job training, together, leverage cultural pull that allowed us to mobilize young men, rather than trying to push men to comply with public health providers’ goals. These intervention activities were designed to promote a social and personal identity that values responsible, respectful relationships (www.genderjustice.org.za).

Finally, we trained the soccer coaches to be the deliverers of the HIV and substance abuse preventive interventions, in a novel fashion. Rather than using a manual that had to be replicated with fidelity for delivery of substance abuse and HIV content, we taught coaches the fundamentals of behavior change and encouraged them to use a series of informal conversations and role plays of real world situations prior to, during, and after the soccer games [25]. HIV risk reduction norms were reinforced by the soccer coaches along with focus on healthy daily routines for eating, sleeping, and exercising, framed around enhancing personal and team performance.

Thus, young unemployed men in two neighborhoods were invited to take part in an intervention using soccer to mobilize young men in an engaging activity, with an added incentive of job training. As a feasibility test, two neighborhoods were randomized to either an immediate intervention or a delayed control condition, with all of the young men in a neighborhood in the same group. Risk outcomes (drug, alcohol, and HIV testing) were monitored prior to and following the intervention, as well as monitoring the broader impact on relationships with families and women with qualitative interviews (reported elsewhere).

METHODS

The Institutional Review Boards of UCLA and Stellenbosch University approved all aspects of the study.

Neighborhood matching

Two matched neighborhoods were selected that were similar in size (450–600 households), have both formal and informal housing, 4–6 shebeens each, with similar access to communal water taps, portable toilets, electricity, within 5 km of a health clinic, and separated by natural boundaries that prevent contamination. UCLA randomized the neighborhoods to either the immediate intervention or the delayed control conditions.

Recruitment

Township men, recruited as research assistants, went door-to-door to all households in the target neighborhoods, checking to see if there were any unemployed young men aged 18–25 years in the household. If such a young man resided in the household at least 4 nights a week, the research assistant described the study and invited the young man to participate, with voluntary informed consent. A one hour assessment interview was conducted at a nearby township site (homes are too small to allow confidential conversations). At the time of recruitment, young men were informed whether their neighborhood would be invited to take part in the soccer intervention immediately or six months later.

Intervention conditions

Grassroot Soccer (GRS) implements soccer-based HIV prevention interventions across sub-Saharan Africa. Coaches from different township neighborhoods were selected as coaches (to safeguard confidentiality). Coaches were selected only if they were not regular attendees at their neighborhood shebeens or known alcohol or drug addicts and could read and write English. Coaches needed to have good reputations, a previous job, and soccer experience. A simple theory was taught to coaches: people change slowly over time, in relationships, with opportunities and practice. Coaches were trained in 11 fundamental skills that are common to 80% of mental health EBI [50]: goal setting, problem solving, praise, social rewards, role playing, coping self-talk, relaxation, emotional self-control, awareness of feelings, attention, and assertive social behaviors [25, 51]. During training, coaches role-played many situations which elicit risky behaviors and create challenging situations for young men. Coaches were also taught about all the local resources for care (health, ID cards, employment training, and community agencies) and methods of referring and ensuring connections are made by young men and agencies. During the pre and post- game periods, coaches discussed the four topics above in the following sequence:

Start with asking the young man to notice the positive events or success in his life today;

Ask the young man about any current concerns; help the man problem solve the situation;

Discuss today’s health goal, roleplay difficult situations needing these skills, and the way to meet the goal.

Soccer practices were held late in the afternoon twice a week, so that the young men would have to abstain from alcohol and drugs for most of the day prior to the soccer practice. Competitive games were held on Saturdays so that families and female partners could attend. There was fruit and water available at the games for all attendees.

The coaches kept a detailed daily log that documented on-time arrival, invitations to test drugs, results of drug and alcohol screening delivered on a random basis, staying the entire time, and red cards for on-the-field play for sportsmanship. Coaches also assigned points based on these behaviors. In interactions, the coach discussed and created role-plays around:

The consequences of alcohol and drug use and the long term physical, social, family, and community effects of abuse; young men abusing drugs and alcohol were referred to health clinics.

Interacting effectively with health care providers, partners, and family members about one’s health, especially HIV, HIV testing, diabetes, TB, and drug abuse.

Creating enjoyable daily routines and a healthy social network, especially with the women in their life in a respectful and caring manner.

Working out and the benefits of exercise.

Young men’s relationships with women and men’s use of violence.

The separate RDTs for drug use each used a Clia RDT, which tested for the presence of amphetamines, cocaine, mandrax, methamphetamines, and morphine. Alcohol use was determined using the REDLINE breathalyzer. An RDT utilizing a clia-waived saliva test with the ability to monitor marijuana (dagga) use in the last 10 days, methamphetamine (tik) use within the last day and crack (mandrax) use within the last three days, was administered on 22 random days.

Any man reaching 55 points was offered vocational training four months filling 35 slots. Men were invited to attend an eight-week course in either electrical or mechanical engineering at a local college. In training, the men were provided with safety jackets and boots as well as books, pens, and other necessary materials. For those earning access to the training, the program was conducted twice a week from 9 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. within walking distance of the neighborhoods; young men could still attend soccer after their vocational training classes. The training was practical, with men practicing the skills they had acquired (e.g., safety, using hand tools, servicing a vehicle, wheel alignments, and typology of cars) on electrical and mechanical engineering projects. The courses were introductory; after successful completion, the participants would be able to apply for an entry level job in or begin a small informal business.

The intervention coordinators from Stellenbosch and Grassroot Soccer randomly monitored practices to ensure that the implementation was proceeding as planned. The coordinators from both Stellenbosch and Grassroot Soccer collaborated with the coaches in problem-solving, brainstorming, and generating action plans when problems occurred in the field. Coaches were asked to log any upsetting events that occurred at any practice or games; the persons involved in the event, violence and the resolution of the conflict. The supervisors’ observations during these visits were reviewed with all coaches, site coordinators, and the research team. Vignettes demonstrating highly effective interactions by the coaches and identifying situations that can be handled more effectively were also featured in a monthly supervision meeting for staff members.

Following six months of intervention delivery, the intervention was mounted in the delayed control neighborhood for six months. A lack of funding prohibited post-intervention assessments of men in the delayed control condition.

Assessments

Data were collected at the baseline interview and six months later using mobile phones customized by a local South African IT company (http://www.mobenzi.com/). Participants received R80 ($6–$8) for the interview. UCLA monitored and checked these files regularly and summaries were provided to the local supervisors. Six months later, 95% (N=134) of men were reassessed – a similar number across conditions.

Socio-demographics and family history [14] including age, partnership status (married, living together, casual), number of moves in the last year, original birthplace, education, and employment were collected. Men self-reported the number and length of sexual relationships, concurrency of sexual partners, frequency, and type of vaginal and anal acts, use of condoms (creating the percentage of condom-protected acts), number of HIV-infected sexual partners, and number of sexual encounters while using alcohol and/or drugs were self-reported for the last six months. A four-item scale on condom use with main and casual partners, carrying condoms, and ease of discussing condoms was summed, with each question rated 1–4.

Hazardous alcohol use, symptoms of dependence, and harmful alcohol use were monitored by the AUDIT [52], with a shift from a 12-month to a 6-month time frame. The AUDIT is a brief, reliable and valid, 10-item questionnaire with four options per question, asking: 1) the days of any alcohol consumption; 2) usual number of drinks in a day when drinking; 3) number of times with six or more drinks in a single day [14].

Substance use was reported in the last three months for: marijuana (dagga), methamphetamine (tik), cocaine (benzene), heroin, and crack (mandrax). The number of days of use in the last 6 months, the largest dose used on a typical day, and the symptoms of withdrawal or symptoms of use were also self-reported for the last three months. From these measures we calculated serious drug use ever (using cocaine, heroin, crack or inhalants) and frequency of use of alcohol, methamphetamine, marijuana, and alcohol. These were the only substances used regularly.

Attitudes towards women were assessed using an 11-item scale adapted from Kaufman et al. [53], the Respecting Women Scale, which includes questions about sharing chores, respecting women, expecting women to listen to their man, having reasons to hit a woman, or not being able to control oneself sexually (Cronbach’s α = 0.36). A scale of controlling attitudes towards women was composed of 13 items rated on a 1–4 scale with items such as, being comfortable with your partner greeting other men, feeling your partner is free to leave a relationship, and needing to know where partner is most of the time(α = 0.53). Violence was reported as the number of times hitting a woman, forcing sexual activity, threatening a partner, physical fights, or being arrested or jailed in the last three months (α = 0.55).

Depression was rated on the short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression measure (CES-D) [54, 55] (20 items, α = 0.88). A 10-item Stress Measure was administered, on which men reported stressful situations during the last month, with each item rated on a four point scale (e.g., difficulties piling up, on top of things, coping with things (α = 0.97).

Analyses

Three types of regression analyses were conducted. Poisson regressions and/or negative binomial regressions were used to evaluate intervention condition, and a time by intervention effect for examining outcomes with counts: frequency of marijuana and a combined index of each substance. Logistic regression analyses were conducted on employment, recent HIV testing, number of sexual partners, depression caseness, and an alcohol dependency as reflected in high AUDIT scores.

RESULTS

Baseline

Almost all (98%) of the young men approached within a neighborhood agreed to participate in the study. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of young men at the baseline assessment. The mean age was 21.9 years and men had typically completed 10th grade at school. Households had about 4.6 members, and most young men lived with their parents (69.7%); only 3.5% lived with a partner. Most lived in informal housing, with 30% having water on the premises; 17% had fathered children, 5% more than one child. Only two young men supported children or other people. Only 20% of young men had ever held a job and half of those men had been fired from a job. More than a third (37%) had more than one sexual partner in the last three months. Almost all (87.8%) had previously used drugs and 100% used alcohol. Forty percent had recently used serious drugs (which includes methamphetamine, crack, and benzene use), with the delayed control condition significantly more likely to engage in serious drugs (p < .0003). Most (77.8%) young men had been tested for HIV in their lifetime and 18% had been tested for TB. Young men typically had a healthy Body Mass Index (M = 21.3; SD=4.1). Violence was similar across conditions: 27% reported they had forced a woman to have sex; almost half (46%) had been arrested; and 22.7% had been sentenced to prison. Men were highly similar across conditions, with only one exception in drug use. At recruitment, no men in either condition were employed or produced income.

Table 1.

Comparison of Participants in Delayed Control (n=70) and Immediate Intervention (n=72) Conditions on the demographic characteristics and Risk Behaviors at the Baseline Assessment.

| Delayed Control (N=70) | Immediate Intervention (N= 72) | Total (N=141) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M/n | %/(SD) | M/n | %/(SD) | M/n | % | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age in years | 22.2 | 1.6 | 21.6 | 2.1 | 21.9 | 1.9 |

| Lives with parents | 43 | 61.4 | 55 | 77.5 | 98 | 69.5* |

| Living alone | 67 | 95.7 | 69 | 97.2 | 136 | 96.5 |

| # of household members | 4.7 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 2.2 |

| Am a father | 10 | 14.3 | 14 | 19.7 | 24 | 17.0 |

| < high school graduation | 52 | 74.3 | 53 | 74.6 | 105 | 74.5 |

| Monthly income | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sexual Behavior | ||||||

| Recent female sex partner(s) | ||||||

| 1 or no partner | 46 | 66.7 | 42 | 59.2 | 88 | 62.9 |

| 2 or more partners | 23 | 33.3 | 29 | 40.8 | 52 | 37.1 |

| Condom Use Score (Range= 0–16) | 4.9 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 1.3 |

| Alcohol Use | ||||||

| AUDIT Questionnaire Score | 8.7 | 8.2 | 11.1 | 7.8 | 9.9 | 8.1 |

| AUDIT Score > 8 (hazardous drinking) | 36 | 51.4 | 44 | 62.0 | 80 | 56.7 |

| Drug Use | ||||||

| Marijuana (Dagga) | ||||||

| # of days used | 25.3 | 38.8 | 15.8 | 32.4 | 20.5 | 35.9 |

| Methamphetamine (Tik) | ||||||

| Lifetime use | 23 | 32.9 | 9 | 12.7 | 32 | 22.7 |

| Recent use | 12 | 17.1 | 2 | 2.8 | 14 | 9.9 |

| Ever used Marijuana or Methamphetamine | 51.1 | 78.1 | 31.8 | 64.8 | 41.4 | 72.1* |

| Mandrax (Lifetime use) | 15 | 21.4 | 9 | 12.7 | 24 | 17.0 |

| Benzene (Lifetime use) | 11 | 15.7 | 11 | 15.5 | 22 | 15.6 |

| Serious Drugs (Lifetime) | 37 | 52.9 | 21 | 29.6 | 58 | 41.1 |

| Monitoring of Risk Status | ||||||

| Ever tested for TB | 34 | 48.6 | 14 | 19.7 | 48 | 34.0*** |

| Ever tested for HIV | 53 | 75.7 | 57 | 80.3 | 110 | 78.0 |

| Recent HIV testa | 16 | 22.9 | 11 | 15.5 | 27 | 19.1 |

| Respecting Women Scale | ||||||

| Attitudes towards Women | 26.2 | 3.0 | 25.7 | 3.3 | 26.0 | 3.1 |

| Desire to Control Women | 32.7 | 4.0 | 33.4 | 4.5 | 33.1 | 4.2 |

| Violence | ||||||

| Total Violence Score | 3.6 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 2.0 |

| Recent Partner Violence | 8.0 | 11.4 | 4 | 5.6 | 12 | 8.5 |

| Threatened to Hurt Partner | 17 | 24.3 | 24 | 33.8 | 41 | 29.1 |

| Forced Partner to Have Sex | 20 | 28.6 | 16 | 22.5 | 36 | 25.5 |

| Physical Family Fights, ever | 23 | 32.9 | 21 | 29.6 | 44 | 31.2 |

| Ever Arrested | 40 | 57.1 | 25 | 35.2 | 65 | 46.1 |

| Ever Gang Member | 13 | 18.6 | 14 | 20.6 | 27 | 19.6 |

| Mental Health | ||||||

| Total Positive Behavior Score | 15.0 | 1.5 | 14.8 | 1.6 | 14.9 | 1.5 |

| Total Depression Score (CES-D, Range= 0–60) | 14.5 | 10.4 | 15.3 | 11.0 | 14.9 | 10.6 |

| Caseness (CES-D > 16) | 17 | 24.3 | 21 | 29.6 | 38 | 27.0 |

| Total Stress Score (Range= 0–40) | 13.3 | 7.1 | 13.6 | 6.8 | 13.5 | 7.0 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Recent refers to activity within the past three months

Engagement

Overall, 11 young men (15%) who were randomized to soccer did not attend any practices or games. Among those who attended any games, the mean number of practices/games attended per youth was 47.3 (SD = 34.4). Most all young men attending practice, arrived on time (M=34.1, SD=23.0). The number of practices reflects the number of coaching sessions. Over time, 71% of young men attended regularly.

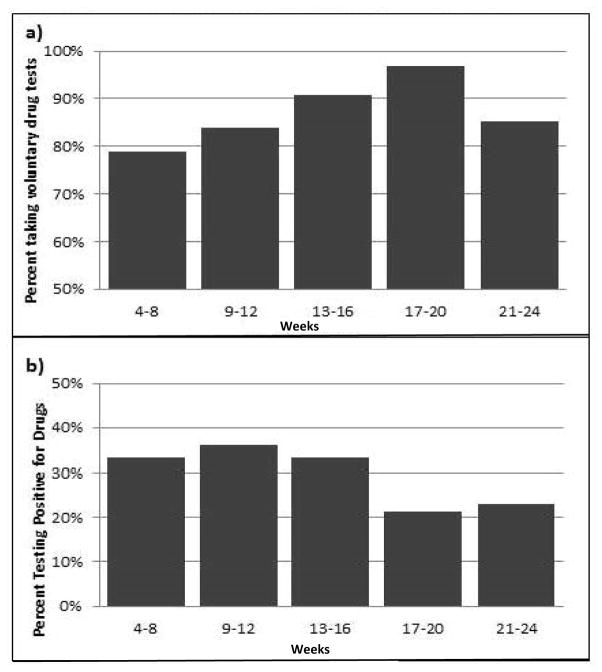

More than half of the young men (52%) completed 19 of 22 RDT. Figure 1a demonstrates the significant increase in the rate of drug testing over time during the soccer activities. Random regressions found significant linear increases in drug testing over each month of the drug testing (p< .05). There was also a quadratic effect: the slope of the rate of drug testing decreased during the last month of the intervention. On the RDT, 73% of young men were alcohol and drug free. There were also significant linear decreases in drug and alcohol use at the soccer practices/games as shown on Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

There graphs show: a) the uptake of voluntary drug testing using Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) at soccer over time, and b) the decrease in players testing positive for drugs (using RDTs) over time.

During the intervention period, 48% (n= 35) of intervention men entered vocational training; 12 graduated, with final test scores on competency from 26% to 96%. Thus, there was a graduation rate of 34%.

Preliminary outcomes

Table 2 summarizes the outcomes comparing the immediate intervention and the delayed control condition. At 6 months, 28.9% of youth in the intervention condition were employed, compared to 9.9% of youth in the delayed control condition. Among those with a job, the income of the young men was similar across condition. The groups were similar in sexual partners and condom use over 6 months. The weighted index of substance use tended to show a significant reduction in the immediate intervention compared to the delayed control condition (p< .07), as did serious drug use (p< .07), crack use (p< .09), and methamphetamine (p< 0.03). The rate of testing for HIV was similar across conditions. While more than three quarters of men reported testing for HIV, only one disclosed an HIV seropositive status to the interviewers. The reports of forcing women to have sex while intoxicated tended to be significantly lower in the intervention condition (p< .08). There were no significant differences across conditions on other measures of violence, attitudes towards women, controlling attitudes towards women, positive behaviors, depression or stress scales.

Table 2.

Summary of Outcome Measures at Baseline and 6 Month Follow-Up Assessments Grouped by the Immediate Intervention and Delayed Control Conditions.

| Baseline | Follow-Up | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Delayed Control (N=70) | Immediate Intervention (N=72) | Total (N=142) | Delayed Control (N=66) | Immediate Intervention (N=69) | Total (N=135) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| M/n | %/(SD) | M/n | %/(SD) | M/n | %/(SD) | M/n | %/(SD) | M/n | %/(SD) | M/n | %/(SD) | |

| Monthly Incomeb | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 403.0 | 1033 | 756.5 | 1229 | 583.7 | 1147* |

| Employmenta | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 9.9% | 20 | 28.9% | 26 | 19%** |

| Sexual Behavior | ||||||||||||

| Recent sex partner(s)a | ||||||||||||

| 1 or no partner | 46 | 66.7 | 42 | 59.2 | 88 | 62.9 | 37 | 56.1 | 42 | 60.9 | 79 | 58.5 |

| 2 or more partners | 23 | 33.3 | 29 | 40.8 | 52 | 37.1 | 29 | 43.9 | 27 | 39.1 | 56 | 41.5 |

| Condom Use Scoreb | 4.9 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 1.1 | 4.9 | 1.2 |

| Alcohol & Drug Use | ||||||||||||

| AUDIT Scoreb | 8.7 | 8.2 | 11.1 | 7.8 | 9.9 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

| AUDIT Score > 8a | 36 | 51.4 | 44 | 62 | 80 | 56.7 | 29 | 43.9 | 26 | 37.7 | 55 | 40.7 |

| Frequency of marijuana use | 25.3 | 38.8 | 15.8 | 32.4 | 20.5 | 35.9 | 23.0 | 37.8 | 12.3 | 28.6 | 17.5 | 33.7† |

| Combines substance use | 51.1 | 78.1 | 31.8 | 64.8 | 41.4 | 72.1* | 46.3 | 76.1 | 24.7 | 57.1 | 35.3 | 67.7* |

| Serious Drug Use Evera | 37 | 52.9 | 21 | 29.6 | 58 | 41.1* | 30 | 45.5 | 21 | 30.4 | 51 | 37.8 |

| Risk Monitoring | ||||||||||||

| Recent HIV testa | 16 | 22.9 | 11 | 15.5 | 27 | 19.1 | 16 | 24.2 | 20 | 29.0 | 36 | 26.7 |

| Respecting Women Scale | ||||||||||||

| Attitudes Towards Womenb | 26.2 | 3.0 | 25.7 | 3.3 | 26.0 | 3.1 | 25.8 | 2.9 | 25.4 | 2.8 | 25.6 | 2.9 |

| Men’s Role with Womenb | 32.7 | 4.0 | 33.4 | 4.5 | 33.1 | 4.2 | 32.1 | 4.0 | 32.4 | 3.1 | 32.2 | 3.5 |

| Violence | ||||||||||||

| Total Scoreb | 3.6 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 1.9* |

| Mental Health | ||||||||||||

| Positive Behavior Scoreb | 15.0 | 1.5 | 14.8 | 1.6 | 14.9 | 1.5 | 14.5 | 1.5 | 14.6 | 1.5 | 14.6 | 1.5 |

| EPDS Score | 14.5 | 10.4 | 15.3 | 11.0 | 14.9 | 10.6 | 10.5 | 5.6 | 10.9 | 7.5 | 10.7 | 6.6 |

| Caseness (CES-D > 16)a | 17 | 24.3 | 21 | 29.6 | 38 | 27.0 | 6 | 9.1 | 8 | 11.6 | 14 | 10.4 |

| Stress Scoreb | 13.3 | 7.1 | 13.6 | 6.8 | 13.5 | 7.0 | 9.1 | 5.0 | 9.3 | 5.5 | 9.2 | 5.2 |

p< .10;

p< .05,

p< .01,

Logistic Regression

Linear Regression Model was built after excluding respondents without income. Although sample size is small (n=30), the distribution of the outcome variable is approximately normal.

Poison (Negative binomial) regression

DISCUSSION

Most HIV EBI are designed, demonstrated efficacious, and then need to be taken up in different settings. Many HIV EBI are implemented in medical settings. These settings are not attractive or effective delivery sites for most men, especially young men. This pilot project was designed to mobilize young men using the attractiveness of soccer and to access the existing funding SETA streams for job training supplied by the South African government. We had very high participation rates of young men in the program: more than 98% of the young men approached, agreed to participate. On an ongoing basis, 71% of young men were regular attendees at the soccer games.

The ability to use soccer for HIV prevention is particularly important, given that FIFA is broadly diffusing soccer globally. FIFA’s diffusion becomes a good vehicle to train young men in social and emotional skills that will be required for successful long-term employment and reductions in drug and alcohol use as well as to engage in medical care and entre for combination prevention strategies. To reach young men with combination prevention strategies [56], it is unlikely that medical settings alone will be particularly useful. Men, particularly young men, underutilize health care services. Access to antiretroviral therapies (ARV) or circumcision may be optimally reached through activities that are highly engaging: soccer or vocational training could be alternative sites for HIV services, rather than medical clinics. Our pilot results suggest how attractive these activities are to young men.

Evaluating men in this feasibility study over the short period of six months, we found significant reductions in alcohol and tended to see reductions in substance use, as well as significant increases in income. These are significant gains among young men who had long histories of risky behaviors.

There were some significant limitations. First, only one neighborhood was involved and a randomized controlled trial must follow this pilot comparison. A larger intervention trial, powered to evaluate significant outcomes has been initiated. Second, no young man disclosed their HIV status and the uptake of recent HIV tests (in the last three months) was not higher among young men in the soccer condition. While drug testing was acceptable and young men discussed HIV testing, the self-reported rates of HIV testing did not improve, as would have been desired.

Third, we only had 35 slots available for vocational training, for men in our project. This program was only mounted for six months. It is likely that soccer would have to be continued for at least several years in order to create a strong enough social network and opportunities for SETA to provide access to training for all young men. Such gradual change is realistic – soccer creates a sustainable activity that is desirable across the lifespan by almost all men. Almost all young men (98%) of the community participated in the study and 85% attended soccer at least once. This removes specialty interventions in health care settings that often miss those at highest risk for HIV and substance abuse. It is important to note that even if not successful for increasing employment, playing soccer has the benefit of providing young men a purpose and activities for daily engagement in prosocial activities.

Fourth, there was a significant quadratic effect in drug testing and drug use in the last month of the program. At that time, there were a number of national strikes throughout South Africa. South African townships are highly politicized contexts. At the last meeting of the soccer team, a few young men who had initially been offered participation in the soccer intervention (but had refused) appeared demanding incentives that they argued were due to them. These activities during the last month point out the importance of how local political situations and contexts can negatively influence the best intervention program. However, the quadratic effects in the uptake of RDT are unlikely to reflect that the intervention effects would not be sustained. The shift with the national strikes indicate how important it is to embed interventions within activities that have sustainable funding streams such as FIFA, so that after the strikes, the program continues. While the coaches’ skills created settings in which young men encouraged each other to engage in risk for five months of the program, the gains in risk reduction were challenged in the context of national unrest and job strikes.

When young men with risk behaviors gather together, there is always an opportunity for the young men to reward each other for dysfunctional behaviors and stimulate even greater risk within the peer group [57, 58]. Yet, following the surge of political upheaval and then a period of quiet, there were not similar problems in the implementation of the delayed control condition over six months. Longer term follow-ups are going to be needed to evaluate the program’s impact.

Finally, there were significant baseline differences in substance abuse, TB testing, and living with a parent between the immediate intervention and the control condition. It would have been expected that the difference would have allowed greater opportunity to improve in the delayed condition, compared to the immediate condition. This did not occur. There was also low internal consistency on several measures. The attitudes towards women scale was used by other researchers [53] and reflects multiple constructs. These are challenges which are not as critical when the primary goal of this study is to evaluate feasibility.

During the soccer we provided food and airtime for prosocial engagement. However, the sample size was too small in this pilot to know if these rewards were needed to enter the vocational training. Young men were embarrassed if not testing clean for drugs and felt social pressure to get drug tested at soccer practice. Peers provided mutual support and encouragement for HIV testing. Soccer, rather than vocational training, was consistently reported as the activity which engaged young men. To know if vocational training is necessary or useful for maintaining gains over time, larger studies will be needed.

There were many aspects of daily life unaffected by the intervention: stress, depression, smoking, and concurrent partnerships. These results are not surprising, given the size of the pilot. EBI in the future need to be embedded in the fabric of daily life that offer repeated opportunities to acquire new skills, interact with positive role models, and shift community norms, especially regarding women and families.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the study’s limitations, the soccer intervention with random RDT for alcohol and drugs was highly engaging and successfully reduced substance abuse over six months. Interventions for young men need to be mounted in settings other than medical clinics. A randomized controlled trial is currently being mounted in 24 neighborhoods in Cape Town, South Africa to more definitively evaluate the effectiveness of this implementation strategy.

Acknowledgments

This Project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grant R34 DA030311; the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grant R24 AA022919; the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment (CHIPTS) NIMH Grant P30 MH58107; the UCLA Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Grant 5P30AI028697; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through UCLA CSTI Grant UL1TR000124; the William T. Grant Foundation; and the National Research Foundation, South Africa.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

No Conflicts of Interest are declared.

References

- 1.UNAIDS, WHO, & UNICEF. Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access, Progress Report 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, WHO, & UNICEF; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraak A. Incoherence in the South African labour market for intermediate skills. J Educ Work. 2008;21:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bärnighausen T, Tanser F, Newell ML. Lack of a decline in HIV incidence in a rural community with high HIV prevalence in South Africa, 2003–2007. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25(4):405–409. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNFPA. UNFPA South Africa: HIV. 2014 Available at: http://countryoffice.unfpa.org/southafrica/2013/05/03/6675/hiv/

- 5.SETA. SETA’s South Africa. Available at: http://seta-southafrica.com/

- 6.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;76:442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leta TH, Sandloy IF, Fylkesnes K. Factors affecting voluntary HIV counselling and testing among men in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:438. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meiberg EA, Bos AER, Onya EH, Schaalma HP. Fear of stigmatization as barrier to voluntary HIV counseling and testing in South Africa. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5(2):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhana D, Pattman R. Researching South African youth, gender and sexuality within the context of HIV/AIDS. Development. 2009;52(1):68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy SP, Panday S, Swart D, et al. Umthenthe Uhlaba Usamila – The South African Youth Risk Behaviour Survey 2002. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Medical Research Council; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunkle KL, Jewkes R, Nduna M, et al. Transactional sex with casual and main partners among young South African men in the rural Eastern Cape: prevalence, predictors, and associations with gender-based violence. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1235–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morojele NK, Kachieng’A MA, Mokoko E, et al. Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(1):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parry CD, Myers B, Morojele NK, et al. Trends in adolescent alcohol and other drug use: findings from three sentinel sites in South Africa (1997–2001) J Adolesc. 2004;27(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Jooste S, Cain D. HIV/AIDS risks among men and women who drink at informal alcohol serving establishments (Shebeens) in Cape Town, South Africa. Prev Sci. 2008;9(1):55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parry CDH, Bennetts AL. Alcohol policy and public health in South Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malow RM, Dévieux JG, Jennings T, Lucenko BA, Kalichman SC. Substance-abusing adolescents at varying levels of HIV risk: Psychosocial characteristics, drug use, and sexual behavior. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(1):103–117. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennell P, Segerstrom J. Vocational education and training in developing countries: Has the World Bank got it right? Int J Educ Dev. 1998;18(4):271–287. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wegner L, Flisher AJ, Chikobvu P, Lombard C, King G. Leisure boredom and high school dropout in Cape Town, South Africa. J Adolesc. 2008;31(3):421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter. Vol. 2. Cape Town, South Africa: Statistics South Africa; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGrath S, Akoojee S. Education and skills for development in South Africa: Reflections on the accelerated and shared growth initiative for South Africa. Int J Educ Dev. 2007;27(4):421–434. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossman CI, Purcell DW, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Veniegas R. Opportunities for HIV combination prevention to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. Am Psychol. 2012;68(4):237–246. doi: 10.1037/a0032711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chovnick G. The past, present and future of HIV prevention: Integrating behavioral, biomedical, and structural intervention strategies for the next generation of HIV prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:143–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond WP, Matthews D, Mohottige, Agyemang A, Corbie-Smith G. Masculinity, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays among community community-dwelling African American men. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1300–1308. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RA, Updegraff JA. Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: tend-and befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychol Rev. 2000;107:411–429. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Becker KD. Adapting evidence-based interventions using a common theory, practices, and principles. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:229–243. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.836453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michielsen K, Chersich MF, Luchters S, De Koker P, Van Rossem R, Temmerman M. Effectiveness of HIV prevention for youth in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials. AIDS. 2010;24(8):1193–1202. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283384791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhana D, Epstein D. ‘I don’t want to catch it’. Boys, girls and sexualities in an HIV/AIDS environment. Gender Educ. 2007;19(1):109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deribe K, Woldemichael K, Wondafrash M, Haile A, Amberbir A. Disclosure experience and associated factors among HIV positive men and women clinical service users in southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King R, Katuntu D, Lifshay J, et al. Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):232–243. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dean HD, Fenton KA. Addressing social determinants of health in the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):1–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chorpita BF. Disruptive innovations for designing and diffusing evidence-based interventions. Amer Psychol. 2012;67:463–476. doi: 10.1037/a0028180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Todd H. Cloning Grameen Bank: Replicating a Poverty Reduction Model in India, Nepal and Vietnam. London: IT Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cons J, Paprocki K. The Limits of Microcredit—A Bangladesh Case. Food First Backgrounder. 2008;14(4):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yunus M. Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty. New York: Public Affairs; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Morduch J. Microfinance Programs and Better Health. JAMA. 2007;298(16):1925–1927. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rawlings LB, Rubio GM. Evaluating the impact of Conditional Cash Transfer programs. The World Bank Research Observer. 2005;20(1):29–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valencia Lomelí E. Conditional Cash Transfers as Social Policy in Latin America: An Assessment of their Contributions and Limitations. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:475–499. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohler HP, Thornton RL. The World Bank Economic Review. 2011. Conditional cash transfers and HIV/AIDS prevention: unconditionally promising? p. lhr041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas D. Intra-household resource allocation: An inferential approach. J Hum Resour. 1990;25(4):635–664. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pitt MM, Khandker SR. The impact of group-based credit programs on poor households in Bangladesh: does the gender of participants matter? J Polit Econ. 1998;106(5):958–996. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatt N, Thang SY. Determinants of repayment in microcredit: Evidence from programs in the United States. Int J Urban Reg Res. 2002;26(2):360–376. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anthony D, Horne C. Gender and cooperation: explaining loan repayment in micro-credit groups. Soc Psychol Q. 2003;66(3):293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sparling PB, Owen N, Lambert EV, Haskell WL. Promoting physical activity: the new imperative for public health. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(3):367–376. doi: 10.1093/her/15.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Messner M. Boyhood, organized sports, and the construction of masculinities. J Contemp Ethnogr. 1990;18(4):416–444. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sewpaul V. On national identity, nationalism and Soccer 2010 Should social work be concerned? Int Soc Work. 2009;52(2):143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Priest N, Armstrong R, Doyle J, Waters E. Policy interventions implemented through sporting organisations for promoting healthy behaviour change. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD004809. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004809.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rotheram-Borus MJ. Expanding the range of interventions to reduce HIV among adolescents. AIDS. 2000;14(1):S33–S40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lightfoot M, Kasirye R, Desmond K. Vocational training with HIV prevention for Ugandan youth. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1133–1137. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0007-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(3):566–79. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chorpita BF, Regan J. Dissemination of effective mental health treatment procedures: Maximizing the return on a significant investment. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(11):990–993. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT-C) In screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(5):844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaufman MR, Shefer T, Crawford M, Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC. Gender attitudes, sexual power, HIV risk: a model for understanding HIV risk behavior of South African men. AIDS Care. 2008;20(4):434–41. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myer L, Smit J, le Roux, Parker S, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(2):147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chisanga N, Kinyanda E, Weiss HA, Patel V, Ayles H, Seedat S. Validation of brief screening tools for depressive and alcohol use disorders among TB and HIV patients in primary care in Zambia. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grossman CI, Purcell DW, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Veniegas R. Opportunities for HIV combination prevention to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):237–246. doi: 10.1037/a0032711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. Am Psychol. 1999;54(9):755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaminer Y. Challenges and opportunities of group therapy for adolescent substance abuse: A critical review. Addict Behav. 2005;30(9):1765–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]