Abstract

We examined the effect of tobacco control policies in Mexico on smoking prevalence and smoking-related deaths using the Mexico SimSmoke model. The model is based on the previously developed SimSmoke simulation model of tobacco control policy, and uses population size, smoking rates and tobacco control policy data for Mexico. It assesses, individually, and in combination, the effect of six tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and smoking-related deaths. Policies included: cigarette excise taxes, smoke-free laws, anti-smoking public education campaigns, marketing restrictions, access to tobacco cessation treatments and enforcement against tobacco sales youth. The model estimates that, if Mexico were to adopt strong tobacco control policies compared to current policy levels, smoking prevalence could be reduced by 30% in the next decade and by 50% by 2053; an additional 470,000 smoking-related premature deaths could be averted over the next 40 years. The greatest impact on smoking and smoking-related deaths would be achieved by raising excise taxes on cigarettes from 55% to at least 70% of the retail price, followed by strong youth access enforcement and access to cessation treatments. Implementing tobacco control policies in Mexico could reduce smoking prevalence by 50%, and prevent 470,000 smoking-related deaths by 2053.

Keywords: Tobacco control policies, smoking prevalence, smoking-attributable deaths, Mexico

Introduction

In response to the heavy toll of tobacco worldwide (Mathers & Loncar, 2006), the World Health Organization (WHO) has set out the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control (FCTC) (World Health Organization, 2005), intended to guide tobacco control policy implementation globally. Substantial evidence indicates that higher cigarette taxes, smoke-free indoor air laws, marketing bans, media campaigns and cessation treatment policy can appreciably reduce adult smoking rates, especially when combined as a comprehensive strategy (Levy, Gitchell, & Chaloupka, 2004; U.S. DHHS, 2000). The MPOWER Report (World Health Organization, 2008), which has defined a set of policies consistent with the FCTC, recommends that each nation: impose taxes on cigarettes that constitute at least 70% of the retail price; implement and enforce comprehensive smoke-free indoor air laws; ban tobacco product marketing; require large pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs; provide access to tobacco cessation treatments; implement a well-funded anti-tobacco public education campaign; and adopt and enforce bans on selling tobacco products to youth.

Evaluating the impact of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and tobacco-attributable deaths is a priority because of the increasing disease burden from tobacco consumption, including in low- and middle-income countries. Most studies have examined the effect of only one or, at most, two policies (e.g., Farrelly, Pechacek, & Chaloupka,2003; Hu, Sung, & Keeler, 1995) because the ability to distinguish their effects on smoking rates is limited by the statistical approaches that are often used. Simulation models can combine information from different sources to estimate the effects of public policies on intended outcomes in complex social systems (Levy, Bauer, & Lee, 2006). Simulation models estimating the effect of tobacco control policies have been developed by Mendez and Warner (2004), Mendez, Warner, and Courant (1998), Ahmad and Billimek (2007) and Levy et al. (2006). The SimSmoke model of Levy et al. simultaneously considers a broad array of tobacco control policies and has demonstrated that it provides accurate estimates of policy effects in a range of countries (e.g., China, Ireland, the USA) (Currie, Blackman, Clancy, & Levy, 2013; Levy, Blackman, Fong, & Chaloupka,in press; Levy, Huang, Currie, & Clancy, 2013; Levy, Rodriguez-Buno, Hu, & Moran, 2014), including middle-income countries (e.g., Brazil, Thailand) (Levy, de Almeida, & Szklo, 2012; Levy, Benjakul, Ross, & Ritthiphakdee, 2008; Levy et al., 2010).

Mexico ratified the FCTC in June 2004. Since 2004, Mexico has adopted stronger advertising restrictions and smoke-free laws in some areas, implemented graphic health warnings covering 30% of the front and 100% of the back of the package, started a quitline and increased cessation treatment coverage, and raised cigarette taxes. However, much remains to be done in order to meet the FCTC requirements, and evaluating the impact of these potential policies will provide critical information to inform policy development and advocacy efforts. Legal challenges have been initiated by the tobacco industry (Ibáñez Hernández, 2013), and it will be important to show the effects of stronger policies on public health.

The goal of this paper is to examine the effect of tobacco control policies in Mexico using the Mexico SimSmoke model. In order to examine the potential effect of tobacco control policies on future smoking prevalence and tobacco-attributable deaths in Mexico, we developed a modified version of SimSmoke. Using data from Mexico on population size, birth rates, death rates and smoking, we developed an initial model to predict smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths for the whole population, as well as by age and gender, from 2013 to 2053, in the absence of tobacco control policies. We then predicted future trends until 2053 in smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths to estimate the effect of an additional set of policies consistent with FCTC/MPOWER recommendations.

Materials and methods

Basic model

We employed a discrete time, first-order Markov process to project future population growth through births and deaths, and smoking rates through smoking initiation, cessation and relapse rates, by age and gender, from the base year to future years. Smoking prevalence is allowed to shift due to changes in tobacco control policies. Smoking-attributable deaths are estimated using smoking rates and mortality risks of smokers and ex-smokers relative to never smokers, similar to standard attribution measures (CDC, 2000). SimSmoke Mexico is described further in a longer report (Levy, Reynales-Shigematsu, Fleischer, Thrasher, & Cumming, 2014).

The base year for the Mexico model is 2002, which precedes the 2004 adoption of FCTC and the implementation of most major tobacco control policies. In addition, smoking prevalence data are available from the Encuesta Nacional de Adicciones (ENA) for 2002 (Kuri-Morales, Gonzalez-Roldan, Hoy, & Cortes-Ramirez, 2006); prevalence had been relatively stable prior to that year (Waters, Saenz de Miera, Ross, & Reynales Shigematsu, 2010). Population and fertility and mortality rates by gender and age were obtained from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Censo de Población y Vivienda, 2013).

Smoking prevalence and initiation, cessation and relapse rates

Current, former and never smoking prevalence data for the baseline year were obtained from the 2002 ENA, a nationally representative survey of the Mexican population between 12 and 65 years old (Kuri-Morales et al., 2006). A current smoker was defined as someone who had smoked 100 cigarettes in his/her lifetime and had smoked in the past 30 days. A former smoker had smoked 100 cigarettes in his/her lifetime, but had not smoked in the past 30 days. Former smokers were also distinguished by the number of years since they had quit. Because the 2002 ENA did not contain information on smokers above age 65, we used an estimate of the current smoking prevalence of the population aged 65 and above from the nationally representative Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutricion (ENSANUT) for the year 2000, adjusted by comparing smoking prevalence from ENA and ENSANUT in earlier years. We used data from the US 1993 Current Population Survey-Tobacco Use Survey (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2001) to distinguish the per cent of former smokers into each of the years quit categories for age 65 and above. Data were also used from the Mexican administration of the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey (ITC Mexico) on policy implementation and cessation rates (Swayampakala et al., 2013).

Due to empirical challenges in measuring initiation and cessation, and in order to insure stability and internal consistency of the model, initiation rates at each age were measured as the difference between the baseline smoking rate at that age and the baseline smoking rate at the previous age. Based on smoking prevalence data and data on stated age of initiation in the ENA sample, we allowed for initiation through age 24.

Using the 2002 ENA, the cessation rate during the past year was calculated as people who were former smokers and had quit in the last year but not the last 30 days/(current smokers + those who had not smoked in the last year, including those who had not smoked in the last 30 days). Cessation and relapse data from the ITC Surveys (Swayampakala et al., 2013) yielded average cessation rates across both males and females of about 7.8% over the period 2007 through 2012. Allowing for the effect of policies since 2002, the 2002 ENA yielded similar cessation rates to the ITC estimates.

Because the cessation rate does not allow for relapse of those who quit less than one year ago, for both genders, a 50% relapse rate (Hughes, Keely, & Naud, 2004) was applied to that measure up through age 44, but no relapse after age 45, which is based on the higher success rates of those at later ages when a smoker often quits for health reasons.

Smoking-attributable deaths

Smoking-attributable deaths (SADs) were determined by the excess mortality risk of current and former smokers compared to never smokers as applied to the number of current and former smokers at each age. Death rates were calculated by age, gender and smoking status (never, current and the former smoker groups) using the data on death rates and 2002 smoking rates, and relative mortality risks. Because risks for Mexico (Reynales-Shigematsu et al., 2006) are likely lower than USA risks due to the lower quantity of cigarettes smoked, we use relative risks of 1.6 for males and 1.5 for females, consistent with risks from other middle-income nations earlier in the tobacco epidemic (Jee, Lee, & Kim, 2006; Wen, Tsai, Chen, & Cheng, 2002). A sensitivity analysis was conducted using USA relative risks of 2.2 for males and 2.0 for females (Burns, Garfinkel, & Samet, 1997).

Policy effects

The policy parameters in the model used to generate the predicted effects are based on thorough reviews of the literature (Levy et al., 2004) and the advice of an expert panel. As a middle-income nation, the effects for Mexico were determined primarily from studies for that nation and high-income nations, but were adjusted to reflect characteristics of a middle-income nation, such as the urban/rural mix and level of income. Policy effect sizes were defined in terms of percentage reductions in smoking prevalence, and initiation and cessation rates. Reductions were applied to the smoking prevalence in the year in which the policy was implemented and, unless otherwise specified, applied to initiation and cessation rates in future years if the policy was sustained. Policies and potential effect sizes are summarised in the Appendix.

For Mexico, we tracked policy levels from the date that the model begins in 2002 until 2013. The level of a policy was based on information MPOWER reports (World Health Organization, 2013), the Tobacco Control Report for the Region of the Americas 2013 (Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2013) and members of the Mexico National Institute of Public Health. Specific policy levels are detailed in a technical report (Levy, Reynales-Shigematsu et al., 2014) and policy effect sizes are shown in the Appendix. Below, we briefly state the policy levels in Mexico for 2013.

Cigarette excise taxes

Since demand studies for Mexico (Saenz de Miera, Thrasher, Reynales-Shigematsu, Hernández-Ávila, & Chaloupka, 2014; Waters et al., 2010) were consistent with those of the USA, we adopted the age-specific prevalence elasticities (i.e., the percentage change in prevalence for a 1% increase in price) used in the USA SimSmoke. For the years 2002–2009, we used inflation-adjusted price data from Waters et al. (2010). For 2008 through 2012, we used data from the ITC (Saenz de Miera et al., 2014). With the addition of a fixed 7 peso tax in 2011, excise tax rate increased to 54% by 2012. We consider increasing the cigarette excise tax to 70% of the retail price, which leads to further price increase due to 13.8% value-added tax (Saenz de Miera et al., 2014).

Smoke-free indoor air laws

A national law in 2008 allowed smoking only in designated areas for worksites, restaurants and other public places. In 2008, Mexico City and Tabasco adopted comprehensive smoke-free policies. Similar bans were put into place in other states between 2011 and 2013, covering 40% of the population. The enforcement level was set to 5 on a 10-point scale based on compliance data from GATS (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, 2009) and ITC (Thrasher, Boado, Sebrie, & Bianco, 2009; Thrasher, Nayeli Abad-Vivero, et al., 2012; Thrasher et al., 2010). In compliance with the FCTC, we consider the implementation of complete smoke-free air laws for worksites, bars and restaurants with strong enforcement.

Marketing restrictions

In 2009, advertising was banned on all television, radio, and billboards and some types of sponsorship, but was allowed in magazines that primarily target adults, in adult-only venues and points of sale, and through the mail (Perez-Hernandez, Thrasher, Rodriguez-Bolanos, Barrientos-Gutierrez, & Ibanez-Hernandez,2012). Promotional discounts, branding and advertising at sponsored events were also banned. Mexico is denoted as having marketing restrictions at 75% of moderate level (3rd level) and 25% low (2nd level) since 2009, with enforcement at 5 of 10. In compliance with the FCTC, we consider the effect of a complete marketing ban, which would include the addition of a ban of advertisements at all points of sale, in all magazines and by mail.

Health warnings

In Mexico, the 2002 law required minimal health warnings, considered weak. The warnings increased to 50% of the back of the pack in 2004, considered moderate, and increased in 2011 to 30% of the pack front with an image and 100% of the back with only text, considered as already strong, and are not further considered.

Tobacco control/media campaigns

Media campaigns have been sporadic and are considered to be at a low level since 2002 (Thrasher, Huang, et al., 2011; Thrasher et al., 2013a; World Health Organization, 2013). We consider the effect of implementing media campaigns at a high level (publicised heavily on TV at least two months of the year and at least some other media).

Cessation treatment policies

Mexico has had NRT and Bupropion available since 2002. By 2012, a national programme to support addictions treatment provided cognitive behavioral therapy for individuals and groups. In 2010, a quitline was established and promoted through new pictorial warnings (Thrasher et al., 2013b; Thrasher, Pérez-Hernández, Arillo-Santillán, & Barrientos-Gutierrez, 2012). Based on the ITC (Borland et al., 2012) and GATS (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, 2009), the brief intervention index was set to a level of 20%. We consider the effect of providing cessation treatments at no cost and active intervention through the health care providers, hospitals, community centres and other health facilities.

Youth access policy

According to the Global Youth Tobacco Surveys (Reynales-Shigematsu, Rodríguez-Bolaños, & Ortega-Ceballos, 2011; Valdes-Salgado, Reynales-Shigematsu, Lazcano-Ponce, & Hernandez-Avila, 2007), over 60% of youth were not refused cigarette purchases at stores in 2003 and 2011. Youth access enforcement is considered at a low level. We evaluate the effect of increasing enforcement to high levels that ensure compliance with the minimum purchase age laws.

Calibration, validation and projection

The model was first calibrated by adjusting the initiation and cessation rates to insure smooth, slightly declining smoking rates by age and gender groups in the absence of policy change. The model was then validated by comparing smoking rates predicted by the model to the 2011 ENA, the 2012 ENSANUT and the 2009 Encuesta Global de Tabaquismo en Adultos (GATS). The model generally validated well by gender and age groups (results not shown).

The model is programmed to project the Mexican population by age and gender, smoking prevalence by age and gender, and smoking-attributable deaths for people aged 15 years and older for 2014 through 2053 with and without policies implemented. We first established the status quo case, where tobacco control policies are maintained at their 2013 level. We then considered the potential effect of future policies that may be implemented consistent with the FCTC-based MPOWER requirements, which are implemented in 2014 and maintained over time through 2053. We first examined the policies in isolation and then together, since research has shown that the most effective tobacco control campaigns use a comprehensive set of policy measures (Jha & Chaloupka, 2000). By comparing the effect of policies to the status quo, we focused on the relative change in smoking prevalence over time (i.e., the change in smoking prevalence from the status quo to the future policy scenario divided by the status quo smoking prevalence). For SADs, deaths averted are calculated as the difference between the number of smoking-related deaths under the new policy and the number of deaths under the status quo. For SADs, we summed the deaths over the period 2014 through 2053 to obtain an approximate cumulative estimate of the total smoking deaths of those who were current or former smokers in 2014.

Results

The effect of stronger FCTC policies on smoking prevalence

First, we present the status quo scenario, in which tobacco control policies remained unchanged from their 2013 levels. In the status quo scenario, male adult smoking is projected to decrease from 21% to 18% between 2013 and 2023, and to 13% over a 40-year projection to 2053 (Table 1). The status quo female smoking prevalence is estimated at 7% in 2013, decreasing to 6% by 2023 and 4% by 2053 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Estimated smoking prevalence for men aged 15 years and older under status quo and policy change scenarios, Mexico, 2013–2053.

| Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2023 | 2033 | 2043 | 2053 | |

| Policies | ||||||

| Status Quo Policies | 21.3% | 20.9% | 18.0% | 15.5% | 13.7% | 12.8% |

| Excise Tax to 70% of Retail Price (VAT at fixed %) | 21.3% | 18.7% | 15.7% | 13.3% | 11.7% | 10.7% |

| Complete Smoke Free & Enforcement | 21.3% | 20.2% | 17.2% | 14.8% | 13.1% | 12.1% |

| Comprehensive Marketing Ban & Enforcement | 21.3% | 19.6% | 16.6% | 14.2% | 12.5% | 11.5% |

| High Intensity Tobacco Control Campaign | 21.3% | 19.7% | 16.6% | 14.1% | 12.5% | 11.6% |

| Cessation Treatment Policies | 21.3% | 20.5% | 16.9% | 14.3% | 12.6% | 11.7% |

| Strong Youth Access Enforcement | 21.3% | 20.7% | 17.1% | 14.3% | 12.4% | 11.3% |

| All of the above | 21.3% | 15.4% | 11.3% | 8.7% | 7.3% | 6.5% |

| % change in smoking prevalence from status quo | ||||||

| Excise Tax to 70% of Retail Price (VAT at fixed %) | – | −10.5% | −12.4% | −14.0% | −15.2% | −16.0% |

| Complete Smoke Free & Enforcement | – | −3.4% | −4.1% | −4.5% | −4.8% | −5.0% |

| Comprehensive Marketing Ban & Enforcement | – | −6.2% | −7.3% | −8.3% | −9.0% | −9.5% |

| High Intensity Tobacco Control Campaign | – | −5.7% | −7.5% | −8.6% | −9.2% | −9.5% |

| Cessation Treatment Policies | – | −1.9% | −5.8% | −7.8% | −8.5% | −8.5% |

| Strong Youth Access Enforcement | – | −1.1% | −5.0% | −7.7% | −10.0% | −11.7% |

| All of the above | – | −26.1% | −37.1% | −43.5% | −47.2% | −49.1% |

Table 2.

Estimated smoking prevalence for women aged 15 years and older under status quo and policy change scenarios, Mexico, 2013–2053.

| Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2023 | 2033 | 2043 | 2053 | |

| Policies | ||||||

| Status Quo Policies | 7.3% | 7.1% | 5.9% | 4.9% | 4.2% | 3.8% |

| Excise Tax to 70% of Retail Price (VAT at fixed %) | 7.3% | 6.4% | 5.2% | 4.2% | 3.6% | 3.2% |

| Complete Smoke Free & Enforcement | 7.3% | 6.9% | 5.6% | 4.7% | 4.0% | 3.6% |

| Comprehensive Marketing Ban & Enforcement | 7.3% | 6.7% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 3.9% | 3.5% |

| High Intensity Tobacco Control Campaign | 7.3% | 6.7% | 5.4% | 4.5% | 3.8% | 3.4% |

| Cessation Treatment Policies | 7.3% | 7.0% | 5.5% | 4.5% | 3.8% | 3.5% |

| Strong Youth Access Enforcement | 7.3% | 7.0% | 5.6% | 4.6% | 3.8% | 3.4% |

| All of the above | 7.3% | 5.3% | 3.7% | 2.7% | 2.2% | 1.9% |

| % change in smoking prevalence from status quo | ||||||

| Excise Tax to 70% of Retail Price (VAT at fixed %) | – | −10.4% | −12.2% | −13.7% | −15.0% | −16.0% |

| Complete Smoke Free & Enforcement | – | −3.4% | −4.1% | −4.7% | −5.0% | −5.2% |

| Comprehensive Marketing Ban & Enforcement | – | −6.2% | −7.3% | −8.3% | −9.0% | −9.6% |

| High Intensity Tobacco Control Campaign | – | −5.7% | −7.7% | −9.0% | −9.7% | −10.0% |

| Cessation Treatment Policies | – | −1.9% | −6.7% | −9.1% | −9.8% | −9.8% |

| Strong Youth Access Enforcement | – | −0.9% | −4.8% | −7.5% | −9.8% | −11.6% |

| All of the above | – | −25.9% | −37.7% | −44.2% | −47.8% | −49.9% |

We then considered a series of policy changes, and their impact on smoking prevalence relative to the status quo for all policy domains (Tables 1 and 2). Because health warnings fully met FCTC requirements in Mexico in 2013, they yielded no additional effect and are not included. If excise taxes were increased to 70% of the retail price, smoking prevalence is projected to decline by 12% relative to the status quo scenario by 2023 and 16% relative to the status quo scenario by 2053. A comprehensive, well-enforced smoke-free ban is predicted to reduce smoking prevalence by 4% relative to the status quo scenario by 2023, increasing to about 5% by the year 2053. A comprehensive, well-enforced marketing ban is predicted to yield a 7% reduction in prevalence by 2023, increasing to a 10% reduction by 2053. For a well-funded and publicised campaign, the model predicts an 8% reduction in smoking prevalence by 2023, increasing to 10% by 2053. Comprehensive smoking cessation treatment policies are projected to reduce smoking prevalence by about 6% by 2023 relative to the status quo, with an approximately 9% reduction by 2053. The effects grow rapidly over time because of their relatively large impact on cessation rates. With the enforcement of youth access laws, the model predicts a 5% relative reduction in smoking rates by 2023 increasing to 12% by 2053. Because youth access laws only affect those under 18 years of age, they have small immediate effects, but their effects increase over time as a larger and larger share of the population is affected by policies preventing youth tobacco sales. The final scenario projected the effect for a combination of all the policies above, including where excise taxes were increased to 70% of retail price. If a comprehensive set of policies is put into place, the smoking prevalence is projected to drop by 41% relative to status quo by 2023, and by almost 50% by 2053.

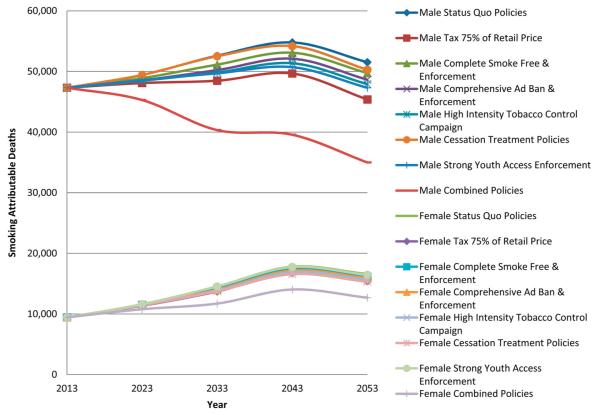

The effects of stronger FCTC policies on smoking-attributable deaths

We also investigated the impact on SADs over the 40-year time period under both the status quo scenario and under implementation of stronger tobacco control policies. Under the status quo scenario, the number of SADs is estimated at nearly 57,000 in 2013 for the whole population (Table 3), with more than 47,000 SADs for men and 9000 SADs for women (Figure 1). SADs are projected to increase to 68,000 in the year 2053 for the whole population. A total of 2.7 million SADs are predicted over the period of 2013–2053.

Table 3.

Estimated SADs for the whole population aged 15 years and older under status quo and policy change scenarios, Mexico, 2013–2053.

| Year |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2023 | 2033 | 2053 | 2013–2053 | |

| Policies | |||||

| Status Quo Policies | 56,763 | 61,024 | 67,131 | 68,109 | 2,695,151 |

| Excise Tax to 70% of Retail Price (VAT at fixed %) | 56,763 | 59,945 | 63,715 | 62,911 | 2,577,327 |

| Complete Smoke Free & Enforcement | 56,763 | 60,389 | 65,324 | 65,880 | 2,636,496 |

| Comprehensive Marketing Ban & Enforcement | 56,763 | 59,967 | 64,225 | 64,558 | 2,601,590 |

| High Intensity Tobacco Control Campaign | 56,763 | 59,895 | 63,703 | 63,550 | 2,579,748 |

| Cessation Treatment Policies | 56,763 | 59,984 | 63,468 | 62,631 | 2,565,020 |

| Strong Youth Access Enforcement | 56,763 | 61,024 | 67,045 | 66,719 | 2,680,702 |

| All of the above | 56,763 | 56,462 | 53,186 | 49,044 | 2,797,719 |

| Absolute change in attributable deaths from status quo | |||||

| Excise Tax to 70% of Retail Price (VAT at fixed %) | – | 1079 | 3416 | 5198 | 117,824 |

| Complete Smoke Free & Enforcement | – | 635 | 1808 | 2229 | 58,655 |

| Comprehensive Marketing Ban & Enforcement | – | 1057 | 2906 | 3551 | 93,561 |

| High Intensity Tobacco Control Campaign | – | 1129 | 3429 | 4559 | 115,403 |

| Cessation Treatment Policies | – | 1040 | 3663 | 5478 | 130,131 |

| Strong Youth Access Enforcement | – | 0 | 87 | 1390 | 14,449 |

| All of the above | – | 4562 | 13,946 | 19,065 | 471,460 |

Figure 1.

Estimated SADs for men and women aged 15 years and older under status quo and policy change scenarios, Mexico, 2013–2053.

For the different policy scenarios, we first considered increasing excise taxes to 70% of the current price, allowing for further effects through the value-added tax. With 70% excise tax, a total of 118,000 premature deaths are averted by 2053. The effects of taxes on deaths are delayed because the effects of cessation on death rates are relatively slow to develop and because the largest tax effects are on youth prevalence.

In terms of other policies, a comprehensive, well-enforced smoke-free ban is predicted to save 59,000 lives over the years 2014–2053. A well-funded, publicised campaign would avert 115,400 premature deaths during the same time period, while a comprehensive, well-enforced marketing ban would avert premature 138,000 deaths. With comprehensive smoking cessation treatment policies, the model projects a total of 130,000 premature deaths averted by 2053. Youth access policies reduce SADs by only 1400 in the year 2053, because the effects of smoking on health occur largely after the age of 40. Between 2014 and 2053, youth access laws are projected to prevent 14,500 total premature deaths. The final modelling scenario, which includes a combination of all policies with excise taxes increased to 70%, projects 19,100 (15,400 males and 3700 females, see Figure 1) fewer annual SADs in the year 2053. The cumulative premature deaths averted between 2014 and 2053 would be 381,000 male and 90,000 female deaths, for a total of 471,000 deaths. Using USA relative risks as a sensitivity analysis, the model projects that 759,000 premature deaths would be averted by 2053 under the combination of all policies with a 70% excise tax.

Discussion

The SimSmoke model estimates that if Mexico were to adopt stronger tobacco control policies as recommended by the FCTC now, smoking prevalence could be reduced by 30% in the next decade and by 50% by 2053. Because of the time delay in tobacco-related deaths, such as cancer, early reductions in smoking prevalence have a relatively small impact on the number of SADs in the short term compared to the potential impact after 40 years. By 2053, approximately 20,000 premature deaths can be averted in that year alone with comprehensive tobacco control policies. Without the FCTC-mandated policies, an additional 470,000 lives and will be lost due to smoking by the year 2053.

Of particular note is the potential role of increasing excise taxes to 70% of the price, which alone can reduce smoking prevalence by 16%. Currently, the excise taxes have an ad valorem component (160% of the price to the retailer) and a specific component (0.35 pesos per cigarette or per 0.75 g), which together account for approximately 54% of the consumer price (Reynales Shigematsu, Thrasher, Lazcano, & Hernández, 2013). We recommend a specific tax on cigarettes, which is most likely to be passed on to consumers (Chaloupka, Straif, & Leon, 2011). As a revenue-generating function for government, tax increases may be one of the more politically feasible policies. Another policy which may be politically feasible is stronger advertising restrictions, particularly at point of sale. With Marlboro as the brand purchased by more than 50% of smokers (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, 2009), stronger point of sales restriction have the potential to reduce the share of this USA brand in favour of a Mexican brand.

We classified Mexico as having strong warning label policies, even though its policy is weaker than recommended in FCTC implementation guidelines (World Health Organization Headquarters, 2008). These guidelines recommend that warnings cover 50% of the front and back of packages, but only 30% of the front is covered in Mexico. Furthermore, the warning on the back of the pack in Mexico only contains text, whereas pictorial imagery is recommended for primary package surfaces. As countries increasingly implement warnings that meet and go beyond FCTC recommendations (Canadian Cancer Society, 2014), data on any additional impact will inform the further refinement of SimSmoke model specifications.

In general, SimSmoke produced reasonably consistent estimates of smoking prevalence when compared to the 2011 ENA, the 2012 ENSANUT and the 2009 GATS surveys. However, we recommend interpreting the results of this study in a conservative manner for several reasons. First, the model’s results depend on the reliability of the data, and the estimated parameters and assumptions used in the models. In addition, the projections do not include the additional premature deaths averted due to reductions in second-hand smoke exposure, or the effects of maternal smoking on the foetus. Another limitation is that the model assumes no effect of income on smoking rates, since past studies yield conflicting effects on the role of income (Fleischer et al., 2015; Jha & Chaloupka, 2000).

Another limitation is that we did not have relative risk estimates specific to Mexico. The estimated relative risks for total mortality of smokers are based on studies from middle-income nations; although later in the smoking epidemic than most middle-income countries, Mexican smokers smoke fewer cigarettes per day, and background risks are likely lower than most high-income nations. With about 50% of smokers who smoke non-daily, and daily smokers smoking 9.4 cigarettes per day (men: 9.7 (8.5–11.0) and women: 8.4 (6.1–10.7) (Encuesta Global de Tabaquismo en Adultos, 2010), we may overestimate the smoking risk. However, the relative risks may increase over time due to earlier average ages of initiation (Doll, Peto, Boreham, & Sutherland, 2004; Peto, Alan, Jillian, & Thun, 2006). For example, data from the 2000 ENA indicate that the average age of initiation dropped from about 17.5 for men and 23.5 for women from the 1930–1959 birth cohorts to 15.7 for men and 16.3 for women from the 1980–1989 birth cohorts (Reynales-Shigematsu et al., 2015). Similar results were obtained using the 2009 GATS and the 2012 ENSANUT. When we used relative risks from the USA, the estimated number of premature deaths increased by about 50%.

The policy modules depend on underlying assumptions, estimated parameters of the predicted effect on initiation and cessation, and assumptions about the interdependence of policies. Knowledge of the different effects of each policy varies (Levy et al., 2004). For example, many studies, with relatively consistent results, have been conducted on the effects of price/taxes and smoke-free policies. However, these studies have been conducted for high-income nations. Studies on media campaigns, advertising bans, health warnings and cessation treatment policies provide a broad range of estimates. In previous work (Levy et al., 2012; Levy et al., in press), we estimated that the effect size of taxes can vary by about 25% around tax parameters, but by 50% around the parameters for other policies (with an upper limit of 100% variation around cessation treatment and youth access policies). The model includes synergies between media campaigns and cessation treatment and smoke-free indoor air policies, but knowledge about the synergistic effects is limited (Levy et al., 2004).

Finally, SimSmoke only considered a limited range of policy options. Additional policies that were not considered may provide targets for future intervention, such as better enforcement of the laws against selling cigarettes as single sticks (Thrasher, Villalobos, Barnoya, Sansores, & O’Connor, 2011; Thrasher, Villalobos, et al., 2009), which is increasingly prevalent in Mexico and may undermine cessation attempts. Some Latin American nations, such as Brazil and Chile, are attempting to ban menthol and other tobacco additives, which could further reduce consumption (Levy et al., 2011). Plain packaging that eliminates brand imagery from cigarette packages has been implemented in Australia and may reduce the appeal of smoking for youth while enhancing warning label impacts. Stronger enforcement of laws against smuggling may be needed if higher cigarettes taxes are imposed. Simulation models that consider these and other additional policy interventions can help shape the future evolution of the FCTC and evaluate its impacts.

In summary, this study demonstrates that nearly a half million premature deaths from smoking could be averted over the next 40 years in Mexico if the government would adopt and actively enforce FCTC-recommended policies. Consistent with similar studies for other countries, we estimate that a large increase in excise taxes alone would substantially reduce the number of lives lost to smoking and is the most efficient way to reduce smoking rates quickly. Tax increases are also likely to increase government revenues (Merriman, Yurekli, & Chaloupka, 2000), part of which can and should be earmarked to implement tobacco cessation treatment, fund anti-tobacco public education campaigns, and enforce and publicise other tobacco control policies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Medical University of South Carolina’s Center for Global Health (CGH) to K.M.C. and funding from the Mexican Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología [Salud-2007-C01–70032] for data collection for ITC Mexico.

Appendix. Policies, description and effect sizes of SimSmoke

| Policy | Description | Potential percentage effecta |

|---|---|---|

| Tax policy | ||

| Actual prices from 2002 to 2012, tax changes after 2010 |

Cigarette price index adjusted for inflation, taxes measure in absolute terms |

For each 10% price increase: 4% reduction ages 15–17, 3% reduction ages 18–24 2% reduction ages 25–34, and 1% reduction ages 35 and above |

| Smoke-free air policies (first four policies are additive) | ||

| Worksite total ban | Ban in all areas | 9.0% reduction |

| Restaurant total ban | Ban in all indoor restaurants in all areas | 3.0% reduction |

| Bar and pubs ban | Ban in all indoor areas of bars and pubs | 1.5% reduction |

| Other places total ban | Ban in 3 of 4 (malls, retail stores, public transportation and elevators) |

1.0% reduction |

| Enforcement and publicity | Government agency is designated to enforce and publicise the laws |

Effects weakened by as much as 50% if 0 enforcement and publicity |

| Mass media campaigns (policies are mutually exclusive) | ||

| Highly publicised campaign | Campaign publicised heavily on TV (at least two months of the year) and at least some other media |

9.75% reduction |

| Moderately publicised campaign | Campaign publicised sporadically on TV and in at least some other media, and a local program |

5.25% reduction |

| Low publicity campaign | Campaign publicised only sporadically in newspaper, billboard or some other media. |

1.5% reduction |

| Marketing bans (first three policies are mutually exclusive) | ||

| Comprehensive marketing ban | Ban is applied television, radio, print, billboard, in-store displays, sponsorships and free samples |

10.0% reduction in prevalence, 12.0% reduction in initiation, 6.0% increase in cessation |

| Moderate ban | Ban is applied all media television, radio, print, billboard |

6.0% reduction in prevalence, 8.0% reduction in initiation, 4.0% increase in cessation |

| Weak ban | Ban is applied some of television, radio, print, billboard |

2.0% reduction in prevalence and initiation only |

| Enforcement and publicity | Government agency is designated to enforce the laws |

Effects weakened by as much as 50% if 0 enforcement |

| Warning labels (policies are mutually exclusive) | ||

| Strong | Labels are large, bold and graphic | 4.0% reduction in prevalence And in initiation, 10.0% increase in cessation |

| Weak | Laws cover less than 1/3 of package, not bold or graphic |

1.0% reduction in prevalence & initiation rates, 2.0% increase in cessation rates |

| Cessation treatment policy | ||

| Complete availability and reimbursement of pharmaco- and behavioural treatments, quit lines, and brief interventions |

NRT provided in stores w/out Rx, Bupropion provided by Rx, provision of treatments in all health facilities, quit line, 100% smoker brief interventions with follow-up |

6.75% reduction in prevalence, 55% increase in cessation |

| Youth access restrictions (policies are mutually exclusive) | ||

| Strongly enforced and publicised | Compliance checks are conducted regularly, penalties are heavy, and with publicity is strong, vending machine and self-service bans |

30.0% reduction for age <16 in prevalence and initiation only, 20.0% reduction for ages 16–17 in prevalence and initiation only |

| Moderately enforced | Compliance checks are conducted sporadically, penalties are potent, and little publicity |

21.0% reduction for age <16 in prevalence and initiation only, 14.0% reduction for ages 16–17 in prevalence and initiation only |

| Low enforcement | Compliance checks are not conducted, penalties are weak, and no publicity |

3% reduction for age <16 in prevalence and initiation only, 2% reduction for ages 16–17 in prevalence and initiation only |

Unless otherwise specified, the same percentage effect is applied as a percentage reduction in the prevalence in the initial year and as a percentage reduction in the initiation rate and a percentage increase in the cessation rate in future years. The effect sizes are shown relative to the absence of any policy. They are based on literature reviews, advice of an expert panel and model validation.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Nancy L. Fleischer http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4371-9133

References

- Ahmad S, Billimek J. Limiting youth access to tobacco: Comparing the long-term health impacts of increasing cigarette excise taxes and raising the legal smoking age to 21 in the United States. Health Policy. 2007;80(3):378–391. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Li L, Driezen P, Wilson N, Hammond D, Thompson ME, Cummings KM. Cessation assistance reported by smokers in 15 countries participating in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) policy evaluation surveys. Addiction. 2012;107(1):197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns D, Garfinkel L, Samet J, editors. Changes in cigarette-related disease risks and their implication for prevention and control. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society Cigarette Package Health Warnings: International Status Report. (4th ed) 2014 Sep; Retrieved from http://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/For20media/Media20releases/2014/Tobacco20Warnings20Oct%202014/CCS-international-package-warnings-report-2014-ENG.pdf.

- CDC Cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 1998. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2000;49(39):881–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(3):235–238. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie LM, Blackman K, Clancy L, Levy DT. The effect of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in Ireland using the IrelandSS simulation model. Tobacco Control. 2013;22(e1):e25–32. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encuesta Global de Tabaquismo en Adultos México 2009. Cuernavaca. 2010 Retrieved from México http://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/gats_rep_mexico.pdf?ua=1.

- Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of tobacco control program expenditures on aggregate cigarette sales: 1981–2000. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22(5):843–859. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer NL, Thrasher JF, Saenz de Miera Juarez B, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Arillo Santillan E, Osman A, Fong GT. Neighbourhood deprivation and smoking and quit behaviour among smokers in Mexico: Findings from the ITC Mexico survey. Tobacco Control. 2015;24:iii56–iii63. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu TW, Sung HY, Keeler TE. The state antismoking campaign and the industry response: The effects of advertising on cigarette consumption in California. American Economic Review. 1995;85(2):85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99(1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez Hernández NA. Legislación para un México 100% libre de humo de tabaco. In: Reynales Shigematsu LM, Thrasher JF, Lazcano Ponce E, Hernández Ávila M, editors. Salud pública y tabaquismo. umen I. Políticas para el control del tabaco en México. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; Cuernavaca: 2013. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2013 Retrieved from http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/poblacion/default.aspx?tema=P.

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública [Retrieved March 31, 2010];Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Mexico. 2009 from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gats/countries/amr/fact_sheets/brazil/

- Jee SH, Lee JK, Kim IS. Smoking-attributable mortality among Korean adults: 1981–2003. Korean Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;28(1):92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jha P, Chaloupka F, editors. Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kuri-Morales PA, Gonzalez-Roldan JF, Hoy MJ, Cortes-Ramirez M. Epidemiology of tobacco use in Mexico. Salud Pública de México. 2006;48(Suppl. 1):S91–s98. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000700011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, de Almeida LM, Szklo A. The Brazil SimSmoke policy simulation model: The effect of strong tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in a middle income nation. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(11):e1001336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Benjakul S, Ross H, Ritthiphakdee B. The role of tobacco control policies in reducing smoking and deaths in a middle income nation: Results from the Thailand SimSmoke simulation model. Tobacco Control. 2008;17(1):53–59. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.022319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Blackman K, Fong GT, Chaloupka F, Fong G, Chaloupka F, Yurekli A, editors. NCI monograph: Tobacco control policies in low and middle income nations. Rockville: The role of tobacco control policies in reducing smoking and deaths in the eighteen heavy burden nations: Results from the MPOWER SimSmoke Tobacco Control Policy Model. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Cho S, Kim Y-M, Park S, Suh M-K, Kam S. An evaluation of the impact of tobacco control policies in Korea using the SimSmoke model: The unknown success story. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(7):1267–1273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Fleischer NL, Thrasher JF, Cumming MK. Mexico SimSmoke: The effects of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and tobacco attributable deaths in Mexico. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.controltabaco.mx/proyectos/modelode-simulacion-del-impacto-de-las-politicas-publica-para-el-control-del-tabaco-simsmoke-mexico. [PubMed]

- Levy D, Rodriguez-Buno RL, Hu TW, Moran AE. The potential effects of tobacco control in China: Projections from the China SimSmoke simulation model. BMJ. 2014;348:g1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Bauer JE, Lee HR. Simulation modeling and tobacco control: Creating more robust public health policies. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(3):494–498. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Gitchell JG, Chaloupka F. The effects of tobacco control policies on smoking rates: A tobacco control scorecard. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2004;10:338–353. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Huang AT, Currie LM, Clancy L. The benefits from complying with the framework convention on tobacco control: A SimSmoke analysis of 15 European nations. Health Policy and Planning. 2013 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DT, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, Blackman K, Vallone DM, Niaura RS, Abrams DB. Modeling the future effects of a menthol ban on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(7):1236–1240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300179. doi:AJPH.2011.300179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez D, Warner KE. Adult cigarette smoking prevalence: Declining as expected (not as desired) American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(2):251–252. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez D, Warner KE, Courant PN. Has smoking cessation ceased? Expected trends in the prevalence of smoking in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;148(3):249–258. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriman D, Yurekli A, Chaloupka F. How big is the worldwide cigarette smuggling problem. In: Jha P, Chaloupka F, editors. Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2000. pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud . Informe sobre Control de Tabaco para la Región de las Américas. OPS; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Hernandez R, Thrasher JF, Rodriguez-Bolanos R, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Ibanez-Hernandez NA. Autorreporte de exposición a publicidad y promoción de tabaco en una cohorte de fumadores mexicanos. Salud Pública de México. 2012;54(3):204–212. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342012000300002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Alan L, Jillian B, Thun M. Mortality from smoking in developed countries 1950–2000 (European Union - 25 countries) 2006.

- Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Campuzano-Rincon JC, Sesma-Vasquez S, Juarez-Marquez SA, Valdes-Salgado R, Lazcano-Ponce E, Hernandez-Avila M. Costs of medical care for acute myocardial infarction attributable to tobacco consumption. Archives of Medical Research. 2006;37(7):871–879. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Guerrero Lopez CM, Hernández-Avila M., Irving, H., Patra J, Jha P. Tendencias del consumo de tabaco en México: Un análisis longitudinal de las encuestas nacionales de salud, Adicciones e Ingreso Gasto 1970–2015. 2015 Unpublished internal working document. [Google Scholar]

- Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Rodríguez-Bolaños R, Ortega-Ceballos P. Encuesta de tabaquismo en jóvenes. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. 2011.

- Reynales Shigematsu LM, Thrasher JF, Lazcano E, Hernández M. Salud pública y tabaquismo, volulmen I. Políticas para el control del tabaco en México. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, México; Cuernavaca: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saenz de Miera B, Thrasher JF, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Hernández-Ávila M, Chaloupka FJ. Tax, price, and cigarette brand preferences: A longitudinal study of adult smokers from the ITC Mexico Survey. Tobacco Control. 2014;23:i80–i85. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayampakala K, Thrasher J, Carpenter MJ, Shigematsu LM, Cupertio AP, Berg CJ. Level of cigarette consumption and quit behavior in a population of low-intensity smokers–longitudinal results from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) survey in Mexico. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(4):1958–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Boado M, Sebrie EM, Bianco E. Smoke-free policies and the social acceptability of smoking in Uruguay and Mexico: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(6):591–599. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Huang L, Perez-Hernandez R, Niederdeppe J, Arillo-Santillan E, Alday J. Evaluation of a social marketing campaign to support Mexico City’s comprehensive smoke-free law. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(2):328–335. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Murukutla N, Perez-Hernandez R, Alday J, Arillo-Santillan E, Cedillo C, Gutierrez JP. Linking mass media campaigns to pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages: A cross-sectional study to evaluate effects among Mexican smokers. Tobacco Control. 2013a;22(e1):e57–65. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Murukutla N, Perez-Hernandez R, Alday J, Arillo-Santillan E, Cedillo C, Gutierrez JP. Linking mass media campaigns to pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages: A cross-sectional study to evaluate effects among Mexican smokers. Tobacco Control. 2013b;22(E1) doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Nayeli Abad-Vivero E, Sebrie EM, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Boado M, Yong HH, Bianco E. Tobacco smoke exposure in public places and workplaces after smoke-free policy implementation: A longitudinal analysis of smoker cohorts in Mexico and Uruguay. Health Policy and Planning. 2012 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Pérez-Hernández R, Arillo-Santillán E, Barrientos-Gutierrez I. Towards informed tobacco consumption in Mexico: Effect of pictorial warning labels in smokers. Revista de Salud Pública de México. 2012;54(3):242–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Swayampakala K, Arillo-Santillan E, Sebrie E, Walsemann KM, Bottai M. Differential impact of local and federal smoke-free legislation in Mexico: A longitudinal study among adult smokers. Salud Pública de México. 2010;52(Suppl. 2):S244–S253. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Barnoya J, Sansores R, O’Connor R. Consumption of single cigarettes and quitting behavior: A longitudinal analysis of Mexican smokers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Dorantes-Alonso A, Arillo-Santillan E, Cummings KM, O’Connor R, Fong GT. Does the availability of single cigarettes promote or inhibit cigarette consumption? Perceptions, prevalence and correlates of single cigarette use among adult Mexican smokers. Tobacco Control. 2009;18(6):431–437. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census . Current population survey, September 1993: Tobacco use supplement file, technical documentation CPS-01. Washington, DC: 2001. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/apsd/techdoc/cps/cpssep98.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. DHHS . Healthy people 2010. Centers for Disease Control, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Atlanta: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Valdes-Salgado R, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Lazcano-Ponce E, Hernandez-Avila M. Before and after the framework convention on tobacco control in Mexico: A comparison from the 2003 and 2006 global youth tobacco survey. Salud Pública de México. 2007;49(Suppl. 2):S155–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters H, Saenz de Miera B, Ross H, Reynales Shigematsu LM. The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in Mexico. International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; Paris: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wen C-P, Tsai S-P, Chen C-J, Cheng T-Y. The mortality risks of smokers in Taiwan collection of research papers presented at tobacco or health in Taiwan. Division of Health Policy Research, National Health Research Institutes; Taipei: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Updated status of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/countrylist/en/index.html.

- World Health Organization . WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER package. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2013: Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship Vol. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/en/index.html.

- World Health Organization Headquarters Guidelines for implementation of Article 11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Packaging and labelling of tobacco products) 2008 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_11.pdf?ua=1.