Abstract

Verticillium dahliae, a notorious phytopathogenic fungus, causes vascular wilt diseases in many plant species resulting in devastating yield losses worldwide. Due to its ability to colonize plant xylem and form microsclerotia, V. dahliae is highly persistent and difficult to control. In this study, we show that the MADS-box transcription factor VdMcm1 is a key regulator of conidiation, microsclerotia formation, virulence, and secondary metabolism of V. dahliae. In addition, our findings suggest that VdMcm1 is involved in cell wall integrity. Finally, comparative RNA-Seq analysis reveals 823 significantly downregulated genes in the VdMcm1 deletion mutant, with diverse biological functions in transcriptional regulation, plant infection, cell adhesion, secondary metabolism, transmembrane transport activity, and cell secretion. When taken together, these data suggest that VdMcm1 performs pleiotropic functions in V. dahliae.

Keywords: Verticillium dahliae, MADS-box transcription factor, microsclerotia formation, pathogenicity, secondary metabolism

Introduction

Verticillium dahliae Kleb. is a devastating soil-borne plant pathogen that causes Verticillium wilt disease, which causes severe damages to diverse plant species worldwide, including economically important crops, ecologically significant trees, and shrubs (Klosterman et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013). For instance, the smoke trees (Cotinus coggygria Scop.), an important colored-leaf tree species, present the famous red-leaf scenery of the Fragrant Hills Park in Beijing, China. However, since 2005, Verticillium wilt disease has caused serious mortality of the smoke trees and impacted the red-leaf landscape (Wang et al., 2013). V. dahliae infects the host plants through the roots and then colonizes and propagates in xylem vessel. Currently, there are no curative fungicides to control this pathogen and cure the infected plants. Melanized microsclerotia, dormant structures formed by V. dahliae, play crucial roles in disease spread and its long-term survival in nature (Green, 1980; Xiao et al., 1998). They germinate and enter the host when suitable hosts and favorable conditions are available (Wilhelm, 1955).

In order to better understand the molecular basis of pathogenesis and microsclerotia development in V. dahliae, many genes have been characterized over the past decades, especially genes involved in signal transduction pathways, such as Fus3 ortholog VMK1 (Rauyaree et al., 2005), MAPK Hog1 (Wang et al., 2016), MAPK kinase Msb2 (Tian et al., 2014), G protein β subunit (Tzima et al., 2012), small GTPase Rac1 (Tian et al., 2015), and cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (Tzima et al., 2010). However, transcription factors acting as integral components of these important signal transduction pathways are relatively less understood in V. dahliae. By contrast, functional analysis of transcription factors is much more advanced in other plant pathogenic fungi, i.e., in Magnaporthe oryzae (Lu et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2015).

The MADS-box transcription factors are highly conserved across fungi, plants, insects, amphibians, and mammals (Shore and Sharrocks, 1995). MADS is named from the initials of its four members: MCM1, AGAMOUS, DEFA, and Serum Response Factor (SRF; Schwarz-Sommer et al., 1990; Shore and Sharrocks, 1995). The MADS-box domain, usually located in the N-terminus, is a conserved region of about 56 amino acids that binds to the cis regulatory consensus sequence CC[T/C][A/T]3NN[A/G]G (Wynne and Treisman, 1992). Generally, there are two MADS-box transcription factor genes Mcm1 and Rlm1 in fungi that can be categorized into two classes: SRF-type and Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2-like (MEF2-like), respectively. However, two additional members Arg80 (SRF-type) and Smp1 (MEF2-like) have been found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Mead et al., 2002). The SRF-type MADS-box genes usually play important roles in diverse cellular processes including fungal growth, osmotic regulation, cell wall and membrane structure, mating type specificity, virulence, and primary and secondary metabolism, while the MEF2-like MADS-box genes play important roles in fungal pathogenicity. To date, the orthologs of S. cerevisiae Mcm1 have been studied in only a few filamentous fungi, including Sordaria macrospora (Nolting and Pöggeler, 2006), Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Qu et al., 2014), M. oryzae (Zhou et al., 2011), Fusarium graminearum (Yang et al., 2015), and Fusarium verticillioides (Ortiz and Shim, 2013). Taken together, fungal Mcm1 orthologs are involved in vegetative growth, stress response, secondary metabolism, and virulence.

The availability of the complete genome sequence of V. dahliae provides a foundation for the study of the mechanisms of microsclerotia formation and pathogenicity (Klosterman et al., 2011; de Jonge et al., 2013). In this study, we addressed the roles of Mcm1 ortholog (VdMcm1) in fungal development, microsclerotia and pathogenicity of V. dahliae.

Materials and methods

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of MADS-box genes in V. dahliae

The MADS-box genes VdMcm1 (VDAG_01770) and VdRlm1 (VDAG_00939) were identified during homology search of the V. dahliae genome database (Broad Institute) using BLASTP program with Mcm1 (CAA88409) and Rlm1 (NP_015236) of S. cerevisiae as a query. The amino acid sequence alignments were performed with ClustalX2.0 (Larkin et al., 2007). The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013) using the neighbor-joining method and the bootstrap test was replicated 1000 times.

Strains and growth conditions of V. dahliae

The V. dahliae strain XS11 was used as the wild-type strain in this study (Wang et al., 2013). All strains were regularly cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates at room temperature. To test the growth rate and conidia production, the cultures were grown on PDA plates, and the experiment was repeated three times. Conidia were harvested from cultures grown in the fresh liquid complete medium (CM; Dobinson et al., 1997) by filtration through two layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem, Germany). The percentage of conidia with abnormal morphology was calculated by randomly recording 100 conidia, and the process was repeated five times. Mycelia were prepared in liquid CM and used for DNA and RNA extractions. For stress response assays, all the strains were grown on CM plates with Sorbitol, NaCl, or KCl. To analyze the cell wall properties, 10 μg/ml calcofluor white (CFW) was used to stain the germinated conidia and mycelia. To test surface hydrophobicity, 20 μl 0.12% bromophenol blue were placed on the surface of 16-day-old fungal colonies grown on PDA, and the colonies were observed after 1 h as previously described (Ruiz-Roldán et al., 2015). The 16-day-old fungal colonies grown on PDA were directly used for RNA isolation, and the obtained total RNA was further used for gene expression analysis. The microsclerotia was induced on a basal medium (BM) as described previously (Neumann and Dobinson, 2003; Xiong et al., 2014). In order to count the number of microsclerotia, a small part of cellulose (diameter 80 mm) was taken for microscopic examination and the relatively separated microsclerotium was regarded as single one. This experiment was repeated three times.

Targeted gene knockout and complementation

VdMcm1 deletion mutants were acquired with the split-marker method (Goswami, 2012). According to this described method, the upstream (~1.4 kb) and downstream (~1.1 kb) flanking sequences of VdMcm1 were amplified with primers V1-F/V1-R and V1-1F/V1-1R, respectively (Table S3). The resulting upstream and downstream fragments were fused with a geneticin-resistant cassette with primers V1-F/Ge-R and Ge-F/V1-1R (Table S3), respectively, by overlap PCR. All the fragments were confirmed by sequencing analysis. The two overlapping fragments were directly transformed into the protoplasts of V. dahliae XS11. The transformants were selected on TB3 medium (Goswami, 2012) with 50 μg/ml geneticin. The successful replacement transformants were initially identified by PCR with primers V1-F/Ge-R, Ge-F/V1-1R, and M1-F/M1-R (Table S3). The Southern blot analysis was performed to confirm the homologous recombination event by using the DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit I in accordance with the manufacturers' protocol (Roche, Germany). The probe fragment used for Southern blot was amplified from genomic DNA with primers Probefor and Proberev. The genomic DNA used for the Southern blot analysis was digested with KpnI. For complementation, a fragment containing the native promoter (~2.0 kb) and the entire open reading frame of VdMcm1 was amplified using primers N1-F/M1-R (Table S3). The resulting PCR products were co-transformed into protoplasts of ΔVdMcm1-5 with hygromycin resistance cassette. Successful complementation was confirmed by reverse transcription PCR with primers RT-F/RT-R (Table S3).

In order to analyze the cellular location of VdMcm1, VdMcm1-GFP fusion was constructed by overlap PCR. A fragment containing a native promoter (~2.0 kb) and coding region of VdMcm1 without stop codon was amplified using primers N1-F/Cd-R with Prime STAR HS DNA Polymerase [Takara Biotechnology (Dalian), China]. The GFP fragment was amplified from pKD5-GFP with primers GFP-F/GFP-R using Prime STAR HS DNA Polymerase. The resulting two fragments were fused together using overlap PCR with primers V1-F/GFP-R. The successfully fused fragment was co-transformed into protoplasts of strain VdMcm1-5 with hygromycin resistance cassette. Successfully integrated transformants (Cp-Mcm1-GFP) were selected with GFP fluorescence and 25 μg/ml hygromycin. Antibiotics of geneticin and hygromycin were bought from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

Digital gene expression profiling analysis

Fungal samples of the wild-type strain and ΔVdMcm1-5 used for digital gene expression profiling analysis were collected from 14-day-old cultures grown on BM, as described by Xiong et al. (2014). Total RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and further purified with a PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Ambion, USA). After RNA quantification and qualification, two single-end sequencing libraries were prepared with NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA) with average insert size of 150–200 bp. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hiseq2500 platform using 50 bp single-end reads at Beijing Novogene, Beijing, China (http://www.novogene.com/index.php).

After the removal of the adapter, ploy-N, and low-quality sequences, reads were aligned to the reference genome of V. dahliae VdLs.17 (Broad Institute) using TopHat (v2.0.9). HTSeq v0.6.1 was used to count the numbers of reads mapped to each gene. Then the RPKM of each gene was calculated based on the length of the gene and the numbers of reads mapped to the gene. Differentially expressed genes were selected using the DEGSeq R package (1.12.0) with the corrected p ≤ 0.005 (adjusted by the Benjamini & Hochberg method) and |Log2(fold-change)| > 1.5. The gene-function annotation was conducted based on Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database. The significantly enriched KEGG pathways were selected using KOBAS (2.0) software with q < 0.05.

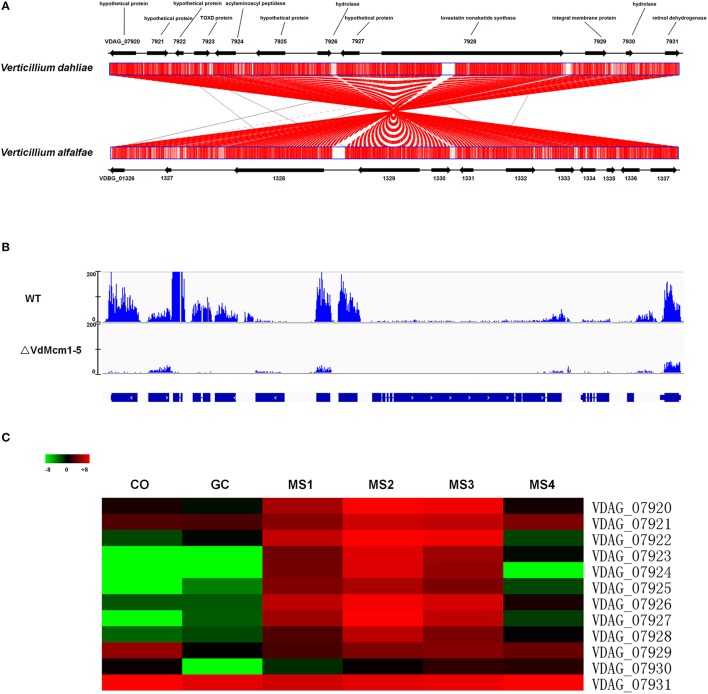

Analysis of the secondary metabolism gene clusters

The secondary metabolism gene clusters in V. dahliae were predicted by the Secondary Metabolite Unknown Region Finder (SMURF; Khaldi et al., 2010). The orthologous genes in Verticillium alfalfae were identified with the BLASTP program by searching in the Verticillium genome database in Joint Genome Institute. The sequence data and annotated information were also acquired from Verticillium genome database (Klosterman et al., 2011). Synteny analysis of the two secondary metabolism gene cluster regions between V. dahliae and V. alfalfae was performed using GATA (Nix and Eisen, 2005). The RNA-Seq coverage data were visualized using Integrative Genomics Viewer (Robinson et al., 2011). The heatmap was drawn using MultiExperiment Viewer (Saeed et al., 2003).

Quantitative real-time PCR assays

For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) assays, cDNA was synthesized using oligo(DT)18 primer and SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA). qRT-PCR reactions were performed using SuperReal PreMix Plus (Tiangen, China) with the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system. The β-tubulin gene was used as an internal reference for all qRT-PCR analyses. Relative expression levels were calculated with 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All primers used in the present study are listed in Table S3.

Pathogenicity assays

For pathogenicity tests, conidia were harvested from 7-day-old cultures grown in liquid CM by filtration through two layers of Miracloth and resuspended at 106 conidia/ml in sterile distilled water. The roots of the 1-year-old smoke tree seedlings were inoculated with conidial suspensions for 10 min. Control plants were mock-inoculated with sterile distilled water. All inoculated smoke trees were then replanted into the soil. Ten smoke tree seedlings were tested per strain, and the experiment was repeated three times. For better observation, 1-month-old tobaccos were also inoculated with 106 conidia/ml conidial suspensions for 1–3 days, and the GFP-expressing strains of wild-type and ΔVdMcm1-5 used for tobacco infection tests were named as WT-GFP and ΔVdMcm1-5-GFP. For scanning electron microscopy, the freshly isolated roots of the smoke trees were inoculated with 107 conidia/ml conidial suspensions for 24 h at room temperature, the water was sopped up with filter papers, then the dried roots were sputtered with Au and used for observation. To examine the ability of conidial adhesion, 105 conidia of each strain were spread over the Hybond™-N+ membranes (GE Healthcare, UK), which were overlaid onto PDA plates at room temperature, and these membranes were then gently washed with 1 ml sterile distilled water after 18 h incubation. Approximately 750 μl conidial suspensions were obtained after gentle washing, and 50 μl conidial suspensions were used to coat the PDA plate. The number of colonies was determined after 5 days of growth on PDA at room temperature. The experiments were repeated three times.

Results

Identification of VdMcm1

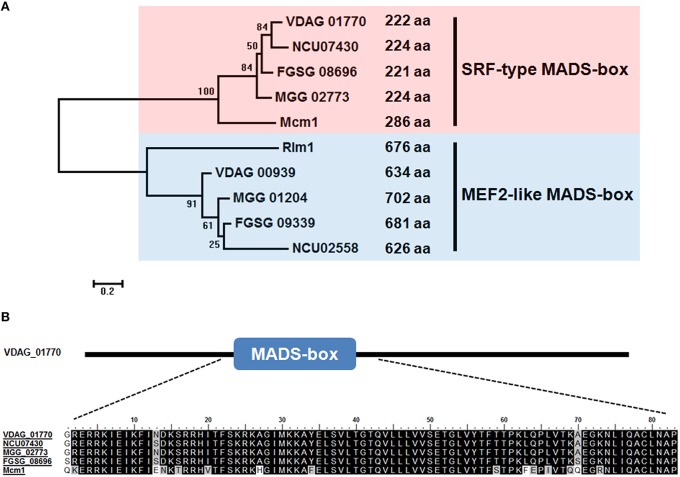

We examined the V. dahliae genome database (JGI) and identified a gene (VDAG_01770) encoding 222 amino acids (aa) protein, which was homologous to S. cerevisiae Mcm1 (54.05% overall identity). Here, VDAG_01770 was designated as VdMcm1. VdMcm1 also shared high degree of homology with Mcm1 from M. oryzae (80.18%) and F. graminearum (78.08%). Phylogenetic analysis suggested that fungal MADS-box genes were divided into two subfamilies: SRF-type (average size about 235 aa) and MEF2-like (average size about 644 aa; Figure 1A). Herein, VdMcm1 belongs to the SRF subfamily. Multiple sequence alignment confirmed that MADS-box domains of Mcm1 orthologs from V. dahliae, S. cerevisiae, M. oryzae, Neurospora crassa, and F. graminearum are highly conserved (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis of VdMcm1. (A) Phylogenetic tree of MADS-box genes in Verticillium dahliae and its homologs from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Mcm1, Rlm1), Neurospora crassa (NCU07430, NCU02558), Magnaporthe oryzae (MGG_02773, MGG_01204), Fusarium graminearum (FGSG_08696, FGSG_09339). VDAG_01770 and VDAG_00939 are homologs of Mcm1 and Rlm1 in V. dahliae, respectively. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the MADS-box domain of VdMcm1 and its homologs from other fungal species.

VdMcm1 contributes to hyphal growth but not to fungal biomass

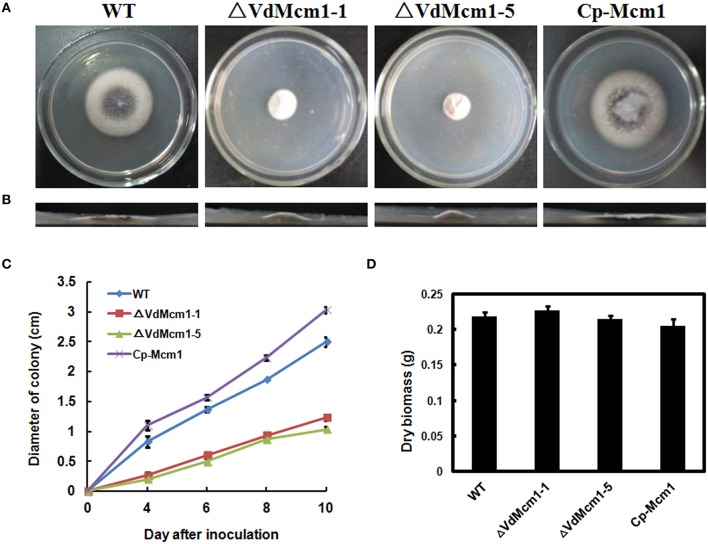

In order to study the role of VdMcm1 in V. dahliae, the entire open reading frame of the gene was replaced with a geneticin-resistant cassette, which generated three ΔVdMcm1 deletion mutants (ΔVdMcm1-1, ΔVdMcm1-5, and ΔVdMcm1-7) with split-marker method (Figures S1A–D). Complementation strains were generated by introducing the VdMcm1 gene with the putative native promoter region (2031 bp) and terminator region (1293 bp) into the ΔVdMcm1-5 mutant, which had been confirmed by Southern blot (Figure S1E). Deletion mutant ΔVdMcm1-5 and complemented strain (Cp-Mcm1) were selected for further analysis. Deletion mutants of VdMcm1 showed significant reduction of hyphal growth on PDA plates (over 50% reduction; Figures 2A,C), and the aerial hyphae of the mutants were more compact than those of the wild-type and complemented strains (Figures 2A,B). However, biomass production of ΔVdMcm1 mutants in liquid medium was similar to that of the wild-type and complemented strains (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

VdMcm1 disruption results in reduced fungal growth. (A) Colony morphology of wild-type strain, VdMcm1 deletion mutants (ΔVdMcm1-1, ΔVdMcm1-5), and the complemented strain after 10 days of growth on PDA plates. (B) Vertical dissection of the colonies on PDA plates. (C) Radial growth rate of the strains on PDA plates. (D) Relative dry biomass of the indicated strains grown in liquid CM for 9 days at 25°C. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

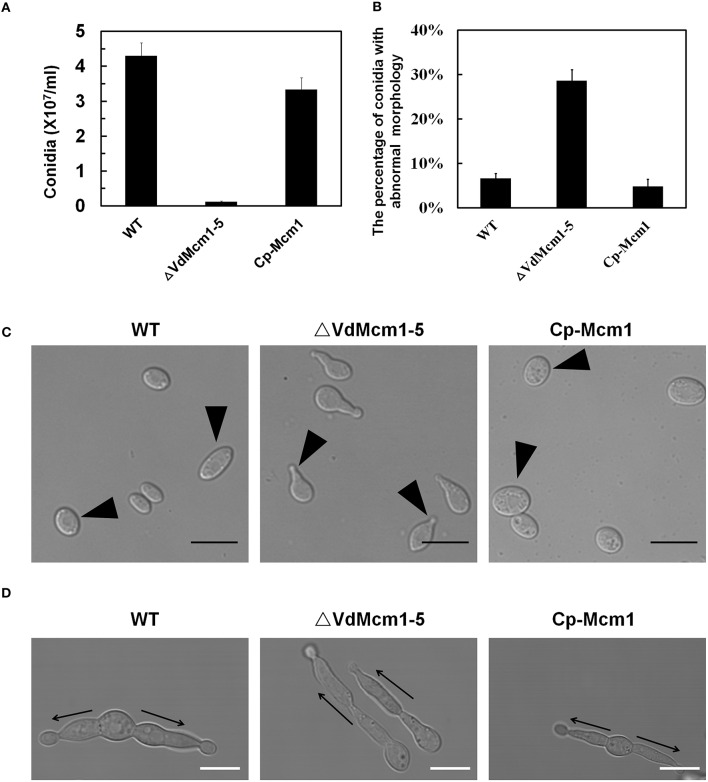

VdMcm1 deletion leads to reduced conidiation and aberrant conidial morphology

Production of conidia in ΔVdMcm1-5 was decreased by 80% compared with that in the wild-type and complemented strains (Figure 3A). Moreover, we found that, in addition to the traditional oval shape of conidia, about 30% conidia produced by the VdMcm1 deletion mutant displayed a polar protrusion (Figures 3B,C). We also noticed that germ tube was only growing along the polar protrusion in the VdMcm1 deletion mutant, whereas most (over 95%) conidia of wild-type and complemented strains exhibited a bidirectional germination (Figure 3D). These results suggest that VdMcm1 is involved in the polar germination of conidia.

Figure 3.

Deletion of VdMcm1 leads to reduced conidial production and abnormal conidial morphology. (A) Conidial production of the wild-type strain, VdMcm1 deletion mutant, and complemented strain after 10 days of growth on PDA plates. (B) The percentage of conidia with abnormal morphology in each strain. (C) Conidial morphology of wild-type strain, VdMcm1 deletion mutant, and complemented strain. Conidia were harvested from cultures in liquid CM for 7 days. The arrowheads indicated normal conidia of wild-type and complemented strains, and abnormal conidia with the protuberance of VdMcm1-5. The scale bars represent 10 μm. (D) Germinated conidia of the wild-type strain, VdMcm1 deletion mutant, and complemented strain after 24 h inoculated in YEPD medium. Arrows indicate growth direction. The scale bars represent 5 μm. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

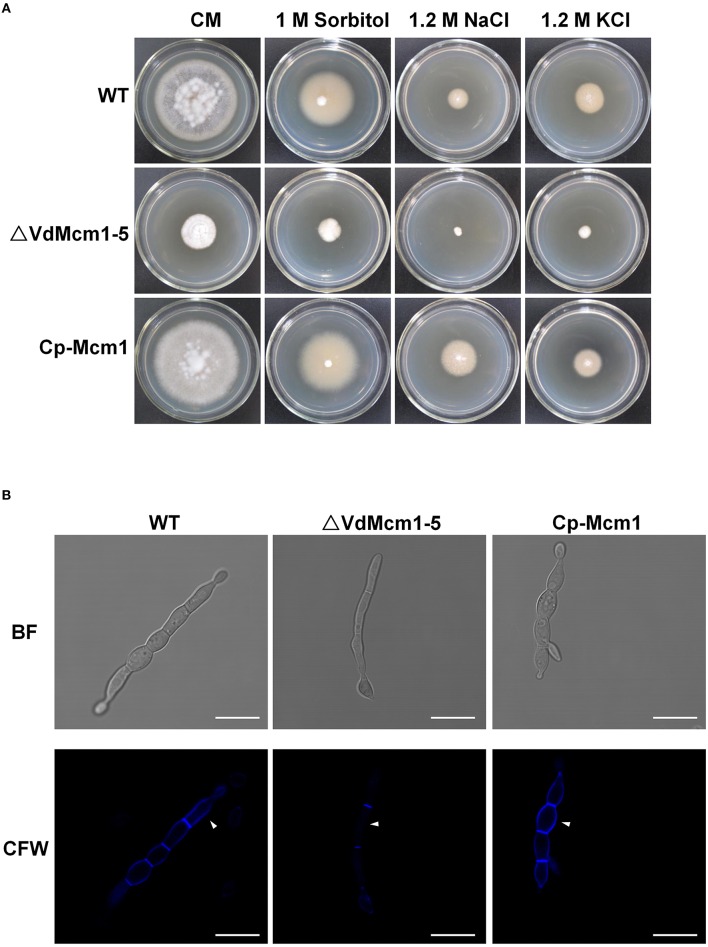

VdMcm1 is involved in cell wall integrity

To test their sensitivity to osmotic stresses, all the strains were cultivated on CM containing 1 M sorbitol, 1.2 M NaCl, and 1.2 M KCl. The results in Figure 4A showed that the ΔVdMcm1-5 displayed slightly increased sensitivity to osmotic stress, especially caused by NaCl and KCl. Relative growth was determined based on the colony diameter at 15 days post-inoculation. Following data analysis using t-test, the difference was considered significant at p < 0.05 (Table 1). To characterize whether VdMcm1 affected the properties of cell wall, CFW staining was used to monitor the chitin deposition in the fungal cell wall. It was obvious that the intensity of CFW staining of cell wall of the wild-type and complemented strains was much higher than that of the ΔVdMcm1-5 strain, suggesting that chitin deposition is reduced in the cell wall of the ΔVdMcm1-5 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

The effect of VdMcm1 on cell wall integrity. (A) Colony morphology of the wild-type strain, ΔVdMcm1-5 and complemented strain after 15 days of growth on CM or CM containing 1 M Sorbitol, 1.2 M NaCl, and 1.2 M KCl. (B) Germinated conidium stained with 10 μg/ml Calcofluor White. The white arrowheads indicate the cell wall stained with Calcofluor White. The scale bars represent 10 μm.

Table 1.

The radial growth of wild type and ΔVdMcm1-5 mutant in response to osmotic stresses with 1 M Sorbitol, 1.2 M NaCl, 1.2 M KCl.

| Compound | WT | ΔVdMcm1-5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony diameter (cm) | % growth | Colony diameter (cm) | % growth | |

| Untreated | 4.20 ± 0.28 | 100 | 1.90 ± 0.1 | 100 |

| 1 M Sorbitol | 2.87 ± 0.06 | 68.3a | 1.25 ± 0.07 | 65.8a |

| 1.2 M NaCl | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 23.8a | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 17.4b |

| 1.2 M KCl | 1.45 ± 0.07 | 34.5a | 0.57 ± 0.06 | 30.0b |

The % growth was determined by using radial growth of treated samples divided the radial growth of untreated controls (100). Different letters “a, b” in the same row indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 and the same letters indicate no significant differences, which were calculated using t-test based on three repetitions.

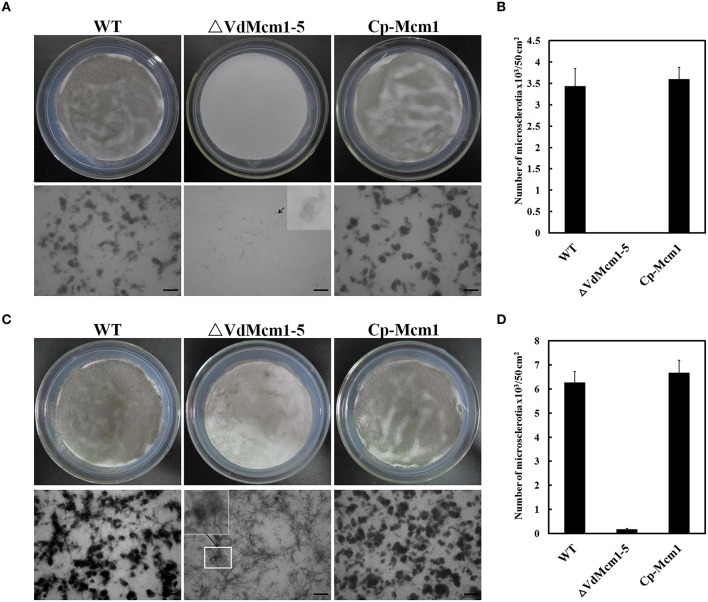

VdMcm1 affects microsclerotia formation and melanin biosynthesis

To examine whether the ΔVdMcm1 deletion strain was defective in microsclerotia production, we observed the microsclerotia formation on BM. After 6 days post-inoculation (dpi), the ΔVdMcm1-5 failed to produce melanized microsclerotia while the wild-type and complemented strains formed melanized microsclerotia (Figure 5A). Under microscopic examination at 6 dpi, about 3000/50 cm2 microsclerotia were formed in the wild-type and the complemented strains, whereas no microsclerotia were produced in ΔVdMcm1-5 (Figure 5B). However, a small number of swollen, melanized hyphae were observed in the ΔVdMcm1-5 (Figure 5B), and the melanin accumulation was significantly compromised in ΔVdMcm1-5. At 8 dpi, about 6000/50 cm2 highly melanized microsclerotia were formed in the wild-type and complemented strains (Figures 5C,D). In contrast, the ΔVdMcm1-5 formed lots of swollen, melanized hyphae instead of microsclerotia, and the melanin accumulation was still significantly reduced in ΔVdMcm1-5 compared with the wild-type and complemented strains (Figures 5C,D). In addition, the hyphae of ΔVdMcm1-5 scarcely gathered together to form microsclerotia. At 14 dpi, the ΔVdMcm1-5 still had significant defects in microsclerotia formation compared with the wild-type and complemented strains (data not shown). Consistent with reduced melanin accumulation in the ΔVdMcm1-5 strain (Figures 2A, 5), genes related to melanin biosynthesis were downregulated in ΔVdMcm1-5 (Figure S2). The results suggest that VdMcm1 positively control microsclerotia formation and melanin biosynthesis.

Figure 5.

Loss of VdMcm1 causes defects in microsclerotia formation. (A) Microsclerotia formation on BM plates with 105 conidia spreading over the cellulose membrane after 6 days of growth. The enlarged view shows the unmelanized and swollen hyphae of ΔVdMcm1-5. The scale bars represent 100 μm. (B) The histogram represents the number of microsclerotia formed by the wild-type strain, ΔVdMcm1-5, and complemented strain on the cellulose membrane (φ = 80 mm) after 6 days of growth. (C) Microsclerotia formation on BM plates after 8 days of incubation. The enlarged view showed the microsclerotia of ΔVdMcm1-5. The scale bars represent 100 μm. (D) The histogram represented the number of microsclerotia formed by wild-type strain, ΔVdMcm1-5, and complemented strain on the cellulose membrane (φ = 80 mm) after 8 days of incubation. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

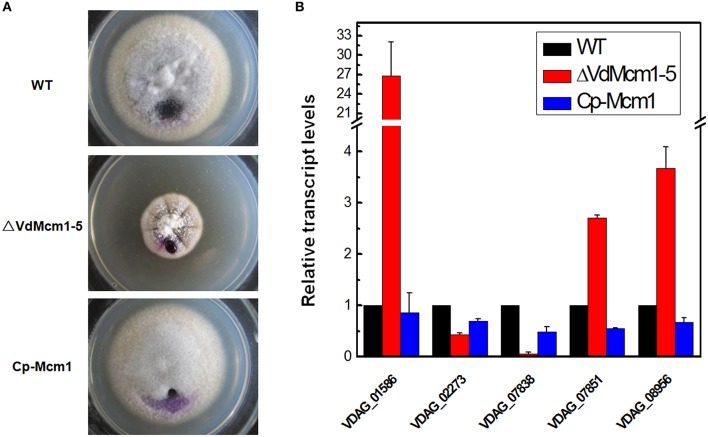

VdMcm1 is involved in surface hydrophobicity

As mentioned above, aerial hyphae in ΔVdMcm1 mutants were more compact than those of the wild-type and complemented strains. To examine whether the surface hydrophobicity was affected after VdMcm1 deletion, we tested the surface hydrophobicity by placing a drop on the surface of colonies. The results showed that the drop remained suspended on the colony surface of the ΔVdMcm1-5, whereas it was soaked into the surface of the wild-type and complemented strains after 1 h (Figure 6A), indicating that VdMcm1 is a negative regulator of surface hydrophobicity.

Figure 6.

Surface hydrophobicity assay and gene expression analysis. (A) Surface hydrophobicity was tested by spotting 20 μl water droplets containing 0.12% bromophenol blue on the surface of 16-day-old colonies grown on PDA plates. The pictures were taken after 1 h of incubation at room temperature. (B) Relative gene expression levels of five hydrophobin genes by quantitative real-time PCR. Total RNA of the wild-type strain, ΔVdMcm1-5, and complemented strain was extracted from the 16-day-old cultures grown on PDA. The β-tubulin gene was used as an internal reference. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the responses to surface hydrophobicity, five genes (VDAG_01586, VDAG_02273, VDAG_07838, VDAG_07851, and VDAG_08956) encoding hydrophobins in the V. dahliae genome were selected for expression analysis. Total RNA was extracted from the 16-day-old cultures grown on PDA. Transcript levels of three genes (VDAG_01586, VDAG_07851, and VDAG_08956) were highly increased in the ΔVdMcm1-5 compared with the wild-type and complemented strains, especially VDAG_01586 (fold-change > 25) and VDAG_08956 (fold-change > 3; Figure 6B). It indicated that these genes might play fundamental roles in surface hydrophobicity. In contrast, VDAG_02273 (over 50% reduction) and VDAG_07838 (over 90% reduction) were downregulated in the ΔVdMcm1-5 (Figure 6B). The results suggest that VdMcm1 is involved in surface hydrophobicity by regulating the expression of hydrophobin encoding genes.

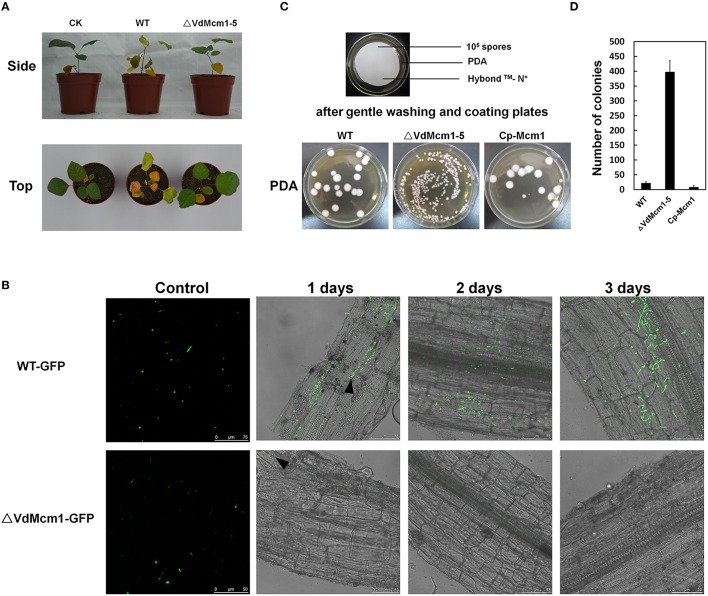

VdMcm1 deletion mutant shows attenuated virulence

The pathogenicity assays showed that smoke tree seedlings inoculated by the ΔVdMcm1-5 exhibited slight chlorosis at 30 dpi (Figure 7A). In contrast, the smoke tree seedlings inoculated with the wild-type strain showed obvious wilt symptoms (Figure 7A). Furthermore, we examined the conidial adhesion on the root of the smoke tree at 1 dpi with scanning electron microscopy. Conidia of the wild-type and complemented strains were attached to root epidermis and germinated, whereas it was hard to see the conidia or germinated conidia on the root epidermis inoculated with ΔVdMcm1-5 (Figure S3). This suggests that VdMcm1 may be involved in the adhesion process during plant infection.

Figure 7.

Pathogenicity assays of VdMcm1 deletion mutants on smoke trees and tobacco seedlings. (A) Side and top views of one-year-old smoke tree seedlings inoculated with 106 spores/ml conidial suspension of the wild-type and ΔVdMcm1-5 for 10 min. The smoke tree seedlings in CK were inoculated with distilled water for 10 min. The pictures were taken at 30 days after inoculation. (B) Microscope observation of 1-month-old tobacco roots inoculated with GFP-expressing wild-type strain (WT-GFP) and ΔVdMcm1-5 (ΔVdMcm1-GFP), respectively. 106 conidia/ml of WT-GFP, ΔVdMcm1-GFP were used. The arrowheads indicated adherent conidia on the root epidermis. The scale bars represent 75 μm. (C) Conidial adhesion tests. 105 conidia harvested from liquid CM were grown on Hybond™-N+ membranes that were overlaid on PDA plates for 18 h. 1 ml distilled water was used to gently wash through the membranes and repeated five times, and about 750 μl conidial suspensions were acquired. Fifty microliter conidial suspensions were spread over the PDA plates. The pictures were taken after 5 days of growth. (D) The number of colonies grown on PDA plates after 5 days. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

To observe the infection process in details, GFP-expressing wild-type (WT-GFP) and ΔVdMcm1-5 (ΔVdMcm1-GFP) strains were used. Conidia of the WT-GFP strain could attach, germinate, and spread onto the root while conidia of ΔVdMcm1-GFP strain almost failed to adhere onto the root (Figure 7B). In addition, the adhesion ability was tested by gently washing the conidia inoculated on the membrane, which was overlaid on the PDA plates after 18 h. The results showed that conidia of the ΔVdMcm1-5 were more likely to be washed away from the membrane than those of the wild-type and complemented strains. After inoculation on PDA plates, 398 colonies were recovered from the ΔVdMcm1-5 while 22 and 9 colonies were recovered from the wild-type and complemented strains, respectively (Figures 7C,D). Taking all the results shown above into consideration, we hypothesize that that VdMcm1 is necessary for the conidial attachment during the infection process.

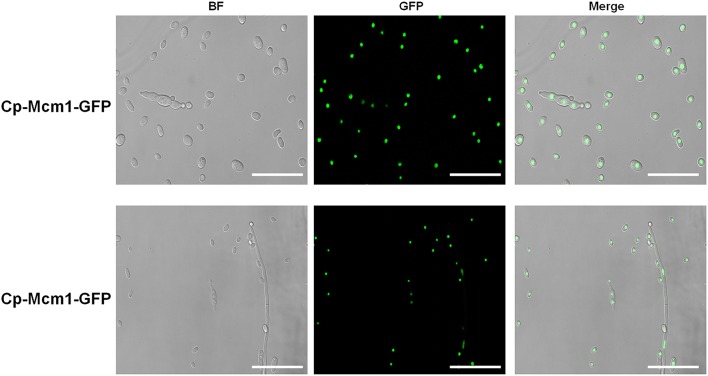

Comparative transcriptomic analysis of ΔVdMcm1 and wild type

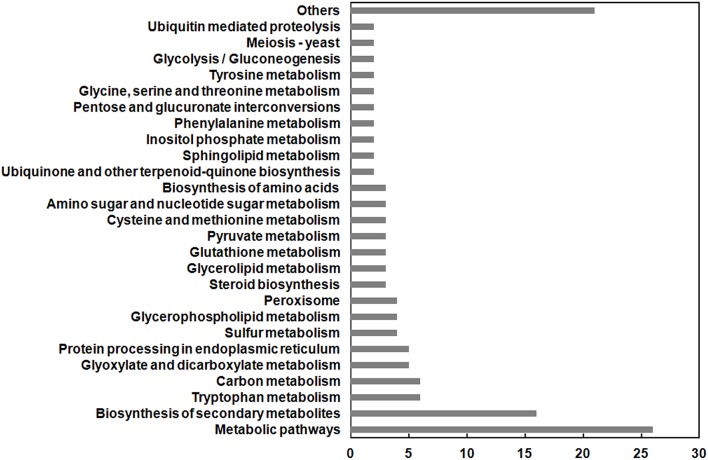

As a conserved transcription factor, Mcm1 is expected to be localized in the nucleus to regulate gene expression. Consistently, VdMcm1 was observed in the nucleus (Figure 8). To identify genes potentially regulated by VdMcm1, the comparative transcriptomic analysis was conducted between the wild-type strain and ΔVdMcm1-5. Overall, differential expression analysis showed that 351 genes were upregulated and 823 genes were downregulated in ΔVdMcm1-5 compared with the wild-type strain. Functional analysis based on GO and KEGG pathways annotation revealed that the 823 downregulated genes were involved in various cellular processes, such as biosynthesis of secondary metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and pyruvate metabolism (Figure 9). Transcriptomic data were confirmed by qRT-PCR to determine the expression levels of several genes (two bZIP genes VDAG_08640 and VDAG_08676, a Crz1 homology gene VDAG_03208, a melanin biosynthesis related gene VDAG_00190, a pyruvate kinase gene VDAG_01206). The results showed that qRT-PCR results and transcriptomic data were well correlated (Figure S4).

Figure 8.

Subcellular localization of VdMcm1. Confocal microscopy of Cp-Mcm1-GFP (VdMcm1-GFP fusion, containing native promoter and coding sequence of VdMcm1 without stop codon and GFP fragment, was introduced into the VdMcm1 deletion mutant) conidia and hyphae, which were harvested from liquid CM. The fluorescence was mainly localized in the nucleus. The scale bars represent 25 μm.

Figure 9.

Functional categories of gene significantly downregulated in ΔVdMcm1-5. The histogram shows the enriched KEGG pathways. The values of x-axis represent the number of genes in each category.

As mentioned above, the ΔVdMcm1-5 mutant showed less chitin deposition of cell wall than that of the wild-type and complemented strains. Consistent with the phenotype, several important genes involved in chitin biosynthesis had significantly reduced expression levels in ΔVdMcm1-5 mutant, such as VDAG_08591 (chitin synthase), VDAG_02580 (chitin synthase), VDAG_03141 (chitin synthase), VDAG_00376 (chitin synthase D).

Combining RNA-Seq data with genome-wide analysis of genes involved in fungal secondary metabolites, we found that six core backbone genes related to secondary metabolism process were regulated by VdMcm1. Among the six genes, five genes (VDAG_03466, VDAG_07928, VDAG_09624, and VDAG_09802) were significantly downregulated in the ΔVdMcm1-5 while one gene (VDAG_03964, surfactin synthetase) was significantly upregulated (Table 2). Further, analysis showed that the entire gene cluster containing VDAG_07928 and other 11 genes (Figure 10A) was significantly downregulated in ΔVdMcm1-5 compared with the wild-type strain (Figure 10B). Additionally, VDAG_07923, VDAG_07924, VDAG_07926, VDAG_07928, VDAG_07929, VDAG_07930, and VDAG_07931 in the cluster encoded TOXD protein, acylaminoacyl peptidase, hydrolase, lovastatin nonaketide synthase, integral membrane protein, hydrolase, and retinol dehydrogenase, respectively (Figure 10A). Comparative analysis also showed that this cluster exhibited high synteny between V. dahliae and V. alfalfae. However, this cluster was not found in other plant pathogenic fungi, such as F. graminearum and M. oryzae. Interestingly, VDAG_07928 was identified to be the only hybrid PKS and NRPS protein in the genome of V. dahliae. Nine out of 12 genes in this cluster, from VDAG_07920 to VDAG_07928, were significantly upregulated during microsclerotia development (Figure 10C). Two additional secondary metabolism gene clusters also showed similar expression pattern of downregulation in VdMcm1 deletion mutant and during microsclerotia formation (Figure S5).

Table 2.

Putative secondary metabolism gene clusters and their expression in V. dahlia.

| Backbone gene_id | Annotated_gene_function | Cluster | SMURF prediction | VdMcm1 vs. WT [Log2(fold change)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDAG_00190.1 | Conidial yellow pigment biosynthesis polyketide synthase | NA | PKS | –3.1161 |

| VDAG_01835.1 | Fatty acid synthase S-acetyltransferase | From VDAG_01835 to VDAG_01842 | PKS | NA |

| VDAG_01856.1 | Phenolpthiocerol synthesis polyketide synthase ppsA | NA | PKS | NA |

| VDAG_02144.1 | L-aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | From VDAG_02132 to VDAG_02147 | NRPS-Like | NA |

| VDAG_03466.1 | Fatty acid synthase S-acetyltransferase | From VDAG_03465 to VDAG_03470 | PKS | –3.2949 |

| VDAG_03964.1 | Surfactin synthetase subunit 3 | From VDAG_03961 to VDAG_03970 | NRPS | 1.706 |

| VDAG_05314.1 | N-(5-amino-5-carboxypentanoyl)-L-cysteinyl-D-valine synthase | From VDAG_05314 to VDAG_05325 | NRPS | NA |

| VDAG_06409.1 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase | From VDAG_06409 to VDAG_06415 | PKS-Like | NA |

| VDAG_07270.1 | Mycocerosic acid synthase | From VDAG_07259 to VDAG_07280 | PKS | NA |

| VDAG_07928.1 | Lovastatin nonaketide synthase | From VDAG_07920 to VDAG_07931 | HYBRID | –3.4231 |

| VDAG_08188.1 | D-alanine-poly(phosphoribitol) ligase subunit 1 | From VDAG_08174 to VDAG_08191 | NRPS-Like | NA |

| VDAG_08448.1 | Lovastatin nonaketide synthase | From VDAG_08443 to VDAG_08448 | PKS | NA |

| VDAG_09534.1 | Aflatoxin biosynthesis polyketide synthase | From VDAG_09526 to VDAG_09535 | PKS | NA |

| VDAG_09624.1 | Peroxisomal-coenzyme A synthetase | From VDAG_09620 to VDAG_09630 | NRPS-Like | –1.9196 |

| VDAG_09654.1 | Hypothetical protein | From VDAG_09647 to VDAG_09663 | NRPS-Like | NA |

| VDAG_09763.1 | Enterobactin synthetase component F | NA | NRPS-Like | NA |

| VDAG_09802.1 | Transferase family protein | From VDAG_09801 to VDAG_09802 | NRPS-Like | –5.841 |

| VDAG_10211.1 | Hypothetical protein | From VDAG_10211 to VDAG_10219 | NRPS-Like | NA |

Bold Gene ids meant that the corresponding cluster contain only one gene. The Log2(fold change) value, the significantly expressed genes were shown. SMURF, a software, was used to predict the secondary metabolism genes and gene clusters in genomic sequence data. NA represented that genes were not differentially expressed in VdMcm1 deletion mutant compared with wild-type strain.

Figure 10.

VdMcm1 regulates genes expression of a secondary metabolism gene cluster. (A) Structure and gene annotation of the secondary metabolism gene cluster in V. dahliae and V. alfalfae. This gene cluster of V. dahliae showed high homology to that of V. alfalfae. Synteny was indicated by red lines. (B) Visualization of RNA-Seq coverage of this secondary metabolism gene cluster in wild-type strain and VdMcm1 deletion mutant. The blue curves indicated reads coverage. (C) Heatmap showing gene expression profiles of genes in the cluster during microsclerotia development. CO and GC represent conidia and conidia germination; MS1–MS4 represents four typical stages during the entire process of microsclerotia formation at 60, 72, 96 h, and 14 days. Log2(FPKM) value was used to draw the picture. Green color represented the negative value of Log2(FPKM), and red color represented the positive value of Log2(FPKM). Black color represented the zero value of Log2(FPKM).

Previously, a V. dahliae homolog of M. oryzae and F. oxysporum C2H2 transcription factor Con7, Vta2 (VDAG_05685) was reported to be involved in fungal adhesion and virulence (Tran et al., 2014). In this study, we found that Vta2 was significantly downregulated in ΔVdMcm1-5. Further, investigation revealed that 61 genes regulated by Vta2 were significantly downregulated in the ΔVdMcm1-5 as well (Table S1). The overlap of genes regulated by both VdMcm1 and Vta2 might be responsible for partially similar phenotypes of the ΔVdMcm1 mutant and the ΔVta2 mutant, such as slow growth rate, reduced virulence and adhesion. However, as far as microsclerotia formation was concerned, VdMcm1 and Vta2 had an opposite effect. Among them, four genes important for early infection were found including pth11-like protein [VDAG_05358, a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) genes], and other three secreted proteins: secreted catalase-peroxidase (VDAG_04826), secreted adhesion genes (VDAG_07185), and one hypothetical protein (VDAG_01806). Further, investigation revealed that 102 secreted proteins with various functions, such as peptidases, glycoside hydrolases, and ligninases (Table S2), were significantly downregulated in ΔVdMcm1-5 compared with the wild-type strain. Importantly, 30 genes encoded small (≤300 aa) and cysteine-rich (≥4 cysteine residues) proteins, which might be candidates for fungal effectors (Table S2). In addition, another 15 GPCR genes, which might be important for signal perception and transduction, were detected to be significantly downregulated in the ΔVdMcm1-5 mutant.

Overall, VdMcm1 functioned as the main regulator of secondary metabolism, infection, and microsclerotia formation.

Discussion

The MADS-box transcription factors are a conserved gene family that contains various numbers of representatives across eukaryotes. In general, there are two MADS-box transcription factors homologous to Mcm1 and Rlm1 of S. cerevisiae in filamentous fungi. Interestingly, Mcm1 was essential in S. cerevisiae. However, Mcm1 orthologs were not essential in other filamentous fungi, such as M. oryzae (Zhou et al., 2011), S. macrospora (Nolting and Pöggeler, 2006), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Didmon et al., 2002), F. graminearum (Yang et al., 2015), and F. verticillioides (Ortiz and Shim, 2013). In this study, the MADS-box transcription factor gene VdMcm1 (VDAG_01770) was identified and characterized in V. dahliae. The results indicated that VdMcm1 possesses pleiotropic functions and regulates fungal growth, microsclerotia formation, and virulence of V. dahliae.

Previous studies revealed that fungal cell morphology was closely related to chitin and glucan contents in fungal cell wall. In this study, we found that the conidia exhibited abnormal morphology in ΔVdMcm1 mutants. In addition, the chitin deposition of cell wall was reduced and genes encoding chitin synthase were differentially downregulated in the ΔVdMcm1 mutant, i.e., VDAG_08591 (FC > 2.5), VDAG_02580 (FC > 1.5), VDAG_03141 (FC > 1.5), VDAG_00376 (FC > 2.5). Additionally, VDAG_00511 (glucan 1,3-beta-glucosidase, FC > 5), VDAG_02814 (glucan 1,3-beta-glucosidase, FC > 5), and VDAG_05658 (chitinase, FC > 5) were also significantly reduced in the ΔVdMcm1 mutant. The reduced expression levels of genes involved in cell wall integrity were possibly responsible for the abnormal morphology. In M. oryzae, deletion of CHS1 led to severe defects in conidia morphology (over 90% conidia were abnormal; Kong et al., 2012). The C2H2 transcription factor Con7p was involved in conidial morphology in M. oryzae (Odenbach et al., 2007) and F. oxysporum (Ruiz-Roldán et al., 2015). Consistent with their morphological defects, chitin content was altered in Con7 deletion mutants in M. oryzae (Odenbach et al., 2007), and chitinase activity was drastically reduced in Con7 deletion mutant in F. oxysporum (Ruiz-Roldán et al., 2015). Interestingly, the conidia of ΔVdMcm1 mutant showed similar morphological defects to the Con7 deletion mutants in M. oryzae and F. oxysporum. In addition, Con7 deletion mutants in V. dahliae and F. oxysporum were reduced in the conidial production compared with the wild-type strain (Tran et al., 2014), and the ΔVdMcm1 mutant also showed defective conidial production.

For phytopathogenic fungi, conidial attachment, and germination are usually the initial steps of infection, and the signal perception or transduction is important for these processes. In this study, we found that conidia of ΔVdMcm1-5 were hardly attached to the root, and a pth11-like GPCR protein (VDAG_05358, FC > 4.5) was significantly downregulated in the VdMcm1 deletion mutant. The pth11-like protein was postulated to perceive the host surface signal during appressorium formation and was essential for pathogenicity in M. oryzae (DeZwaan et al., 1999). Furthermore, other 15 putative GPCR genes were also differentially downregulated in the VdMcm1 deletion mutant, i.e., VDAG_02933 (Microbial Opsin), VDAG_00541 (Family C-like GPCR), and VDAG_03447 (Hlyll_domain GPCR). GPCRs convey the external signals to heterotrimeric G proteins, which then activate the cyclic adenosine monophosphate and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. These signaling pathways play roles in fungal growth, mating, and virulence (Servin et al., 2012).

Secreted proteins of plant pathogens play important roles in host infection and colonization, and some of them, known as effectors, showed critical functions during infection process (Oliva et al., 2010; de Jonge et al., 2011; Vargas et al., 2015). In the genome of V. dahliae, more than 700 secreted proteins were identified (Klosterman et al., 2011). In this study, significantly reduced expression levels of 102 putative secreted protein encoding genes were detected in ΔVdMcm1-5 mutant compared with the wild-type strain. Some of them, such as VDAG_09343 (peptidases), VDAG_02733 (peptidases), VDAG_02906 (glycoside hydrolases) and VDAG_06155 (pectate lyase), might be important for the infection process as they might degrade the plant cell wall and could also act as fungal effectors due to small (≤300 aa) and cysteine-rich (≥4 cysteine residues) properties (Table S2).

Hundreds of putative target genes of VdMcm1 were identified by comparative transcriptomic analysis between the wild-type strain and ΔVdMcm1-5 mutant. Remarkably, dozens of downstream genes regulated by VdMcm1 were also identified as putative target genes of Vta2 (Tran et al., 2014). Some phenotypes of the VdMcm1 deletion mutant were similar to the Vta2 deletion mutant. First of all, the growth rate of these two mutants was significantly reduced. Secondly, both mutants displayed drastic reduction of conidiation. Thirdly, the virulence of both mutants was reduced. However, the mechanism for the reduced virulence was different between these two mutants. Conidia of VdMcm1 deletion mutants failed to attach onto the roots while the Vta2 deletion mutants could adhere and germinate on the roots but not colonize host stems (Tran et al., 2014). Although the morphology of conidia was not mentioned in Vta2 deletion mutant, the conidial morphology of VdMcm1 deletion mutant was abnormal with a protuberance. Besides conidial morphology, the roles of VdMcm1 and Vta2 in microsclerotia formation are opposite. VdMcm1 is a positive regulator in microsclerotia formation, whereas Vta2 is a negative regulator. We believe that it will provide important insights into microsclerotia formation to study the relationship between VdMcm1 and Vta2, although it will be a big challenge.

Secondary metabolites play important roles in virulence in fungi. Fungal secondary metabolites are mainly polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides, terpenes, and indole alkaloids, and the genes responsible for their biosynthesis are usually arranged in clusters (Keller et al., 2005; Fox and Howlett, 2008). Among them, melanin (a polyketides) is one of the most noticeable secondary metabolites produced by V. dahliae that would continuously accumulate during microsclerotia development (Bell et al., 1976; Stipanovic and Bell, 1976; Duressa et al., 2013; Xiong et al., 2014). Here, the VdMcm1 deletion mutants showed obvious defect in melanin accumulation, suggesting that VdMcm1 is essential for melanin production. In addition, using comparative transcriptomics, we discovered that several putative secondary metabolism gene clusters, including the only one PKS/NRPS hybrid gene cluster in V. dahliae, were regulated by VdMcm1. More importantly, putative Mcm1 binding site (CC[T/C][A/T]3NN[A/G]G) was found in the promoter sequences of two PKS/NRPS hybrid cluster genes VDAG_07924 and VDAG_07927, which were not expressed in the VdMcm1 deletion mutant (data not shown). VdMcm1 orthologs in other fungi are also involved in secondary metabolism. For example, FgMcm1 is involved in deoxynivalenol (DON) production, i.e., the deletion of FgMcm1 leads to a significant reduction of DON production (Yang et al., 2015). The expression levels of gene clusters involved in secondary metabolites production were downregulated in the FgMcm1 deletion mutant including PKS2, PKS5, PKS9, NRPS7, and NRPS 14 gene clusters (Yang et al., 2015). Similarly, FvMcm1 deletion mutant was dramatically reduced (about 50%) in the Fumonisin B1 production and the expression of PKS related genes compared with the wild-type strain (Ortiz and Shim, 2013).

Microsclerotia play important roles in disease cycles. They germinate to hyphae and infect the host when conditions are suitable. In this study, we found that microsclerotia formation was dramatically reduced in VdMcm1 deletion mutant. Consistent with the reduced microsclerotia formation, genes involved in this process were downregulated in VdMcm1 deletion mutant, such as melanin biosynthesis genes VDAG_00189 and VDAG_03665, a fad binding domain-containing protein VDAG_01149, a cytochrome p450 VDAG_03650, and a bZIP transcription factor VDAG_08640 (Duressa et al., 2013; Xiong et al., 2014). Furthermore, a hydrophobin-encoding gene VDAG_02273 reported to be involved in microsclerotia formation (Klimes and Dobinson, 2006; Klimes et al., 2008) showed reduced transcript level in ΔVdMcm1-5. The results indicated that VdMcm1 controls microsclerotia formation by regulating the downstream genes that are involved in microsclerotia development.

In summary, the results displayed in this study demonstrate that VdMcm1 plays important roles in fungal development, secondary metabolism, and virulence in plant pathogenic fungus V. dahliae. The results provide evidence that VdMcm1 plays pleiotropic roles through regulating hundreds of downstream genes. As for disease control, VdMcm1 is a potential target to control the fungal growth, microsclerotia development, and virulence in V. dahliae, although the genetic and signaling networks related to the microsclerotia development and pathogenicity of V. dahliae remain unclear. The data presented in this study can facilitate the exploration of upstream activators and downstream effectors of VdMcm1 and explain how they function in microsclerotia formation and virulence.

Author contributions

YW, CT, and DX designed the experiments. DX and LT performed the experiments and the data analyses. DX and YW prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570636) to YW.

Availability of supporting data

DGE data were submitted to the NCBI SRA database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/) with the accession number: SRR2087157 (wild type), SRR2087158 (ΔVdMcm1-5).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01192

The strategy of gene replacement and validation of gene deletion mutants. (A) Gene replacement strategy for the deletion of VdMcm1. The split-marker method was used. The entire coding sequence of VdMcm1 was replaced with a geneticin resistance cassette. (B) Screen the geneticin resistance transformants by PCR with split-marker primers (5F: V1-F and Ge-R; 3F: Ge-F and V1-1R). (C) Validation of the VdMcm1 deletion mutants by PCR with primers M1-F and M1-R. The deletion mutants showed one band (the length of geneticin resistance cassette), the wild-type strain showed one different band (the length of VdMcm1) whereas the ectopic mutants contained two bands: one for the geneticin resistance cassette, one for VdMcm1. (D) Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed to validate the deletion and reintroduction of VdMcm1. (E) Confirmation of the VdMcm1 deletion mutant by Southern blot with a VdMcm1 probe. Genomic DNA of wild-type strain and VdMcm1 deletion mutant were digested with Kpn I.

Expression analysis of genes related to melanin biosynthesis. Calculation the transcript levels of five melanin biosynthesis genes with qRT-PCR. The β-tubulin gene was used as a reference gene for the expression analyses. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Scanning electron microscopy of smoke tree roots inoculated with conidial suspensions. Arrows show germinated conidia in the wild-type and complemented strains. The pictures were taken after 24 h of incubation with 106 conidia/ml.

Validation of mRNA-Seq expression patterns by qRT-PCR. The qRT-PCR results of the selected genes showed similar expression patterns to those detected by mRNA-Seq. VDAG_08640 and VDAG_08676 are bZIP transcription factor genes; VDAG_03208 is a C2H2 transcription factor gene; VDAG_00190 is a gene involved in melanin biosynthesis; VDAG_01206 is a pyruvate kinase gene which catalyzes the generation of pyruvate from phosphoenolpyruvate in glycolysis pahtway. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

VdMcm1 regulates genes expression of secondary metabolism gene clusters. (A) Line graph showing the expression pattern of secondary metabolism gene clusters in ΔVdMcm1-5 and wild-type strain. Log2(FPKM) value was used to draw the picture. (B) Heat map showed gene expression profiles of the gene clusters during microsclerotia development (Xiong et al., 2014). CO and GC represent conidia and conidial germination; MS1-MS4 represents four typical stages during the entire process of microsclerotia formation at 60, 72, 96 h, and 14 days.

A list of genes regulated by both VdMcm1 and Vta2.

A list of secreted protein-encoding genes significantly downregulated in ΔVdMcm1.

All the primers used in this study.

References

- Bell A. A., Puhalla J. E., Tolmsoff W. J., Stipanovic R. D. (1976). Use of mutants to establish (+)-scytalone as an intermediate in melanin biosynthesis by Verticillium dahliae. Can. J. Microbiol. 22, 787–799. 10.1139/m76-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge R., Bolton M. D., Kombrink A., van den Berg G. C., Yadeta K. A., Thomma B. P. (2013). Extensive chromosomal reshuffling drives evolution of virulence in an asexual pathogen. Genome Res. 23, 1271–1282. 10.1101/gr.152660.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge R., Bolton M. D., Thomma B. P. (2011). How filamentous pathogens co-opt plants: the ins and outs of fungal effectors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 400–406. 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeZwaan T. M., Carroll A. M., Valent B., Sweigard J. A. (1999). Magnaporthe grisea pth11p is a novel plasma membrane protein that mediates appressorium differentiation in response to inductive substrate cues. Plant Cell 11, 2013–2030. 10.1105/tpc.11.10.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didmon M., Davis K., Watson P., Ladds G., Broad P., Davey J. (2002). Identifying regulators of pheromone signalling in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Curr. Genet. 41, 241–253. 10.1007/s00294-002-0301-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobinson K. F., Lecomte N., Lazarovits G. (1997). Production of an extracellular trypsin-like protease by the fungal plant pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Can. J. Microbiol. 43, 227–233. 10.1139/m97-031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duressa D., Anchieta A., Chen D., Klimes A., Garcia-Pedrajas M. D., Dobinson K. F., et al. (2013). RNA-seq analyses of gene expression in the microsclerotia of Verticillium dahliae. BMC Genomics 14:607. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox E. M., Howlett B. J. (2008). Secondary metabolism: regulation and role in fungal biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 481–487. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami R. S. (2012). Targeted gene replacement in fungi using a split-marker approach. Methods Mol. Biol. 835, 255–269. 10.1007/978-1-61779-501-5_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R., Jr. (1980). Soil factors affecting survival of microsclerotia of Verticillium dahliae. Phytopathology 70, 353–355. 10.1094/Phyto-70-353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller N. P., Turner G., Bennett J. W. (2005). Fungal secondary metabolism - from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 937–947. 10.1038/nrmicro1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldi N., Seifuddin F. T., Turner G., Haft D., Nierman W. C., Wolfe K. H., et al. (2010). SMURF: genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47, 736–741. 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes A., Amyotte S. G., Grant S., Kang S., Dobinson K. F. (2008). Microsclerotia development in Verticillium dahliae: regulation and differential expression of the hydrophobin gene VDH1. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45, 1525–1532. 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes A., Dobinson K. F. (2006). A hydrophobin gene, VDH1, is involved in microsclerotial development and spore viability in the plant pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43, 283–294. 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman S. J., Atallah Z. K., Vallad G. E., Subbarao K. V. (2009). Diversity, pathogenicity, and management of verticillium species. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 39–62. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman S. J., Subbarao K. V., Kang S., Veronese P., Gold S. E., Thomma B. P., et al. (2011). Comparative genomics yields insights into niche adaptation of plant vascular wilt pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002137. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L. A., Yang J., Li G. T., Qi L. L., Zhang Y. J., Wang C. F., et al. (2012). Different chitin synthase genes are required for various developmental and plant infection processes in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002526. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong S., Park S. Y., Lee Y. H. (2015). Systematic characterization of the bZIP transcription factor gene family in the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 1425–1443. 10.1111/1462-2920.12633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Cao H., Zhang L., Huang P., Lin F. (2014). Systematic analysis of Zn2Cys6 transcription factors required for development and pathogenicity by high-throughput gene knockout in the rice blast fungus. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004432. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead J., Bruning A. R., Gill M. K., Steiner A. M., Acton T. B., Vershon A. K. (2002). Interactions of the Mcm1 MADS box protein with cofactors that regulate mating in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4607–4621. 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4607-4621.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M. J., Dobinson K. F. (2003). Sequence tag analysis of gene expression during pathogenic growth and microsclerotia development in the vascular wilt pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38, 54–62. 10.1016/S1087-1845(02)00507-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nix D. A., Eisen M. B. (2005). GATA: a graphic alignment tool for comparative sequence analysis. BMC Bioinform. 6:9. 10.1186/1471-2105-6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolting N., Pöggeler S. (2006). A MADS box protein interacts with a mating-type protein and is required for fruiting body development in the homothallic ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. Eukaryotic Cell 5, 1043–1056. 10.1128/EC.00086-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbach D., Breth B., Thines E., Weber R. W., Anke H., Foster A. J. (2007). The transcription factor Con7p is a central regulator of infection-related morphogenesis in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 293–307. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva R., Win J., Raffaele S., Boutemy L., Bozkurt T. O., Chaparro-Garcia A., et al. (2010). Recent developments in effector biology of filamentous plant pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 12, 705–715. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz C. S., Shim W. B. (2013). The role of MADS-box transcription factors in secondary metabolism and sexual development in the maize pathogen Fusarium verticillioides. Microbiology 159, 2259–2268. 10.1099/mic.0.068775-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X., Yu B., Liu J., Zhang X., Li G., Zhang D., et al. (2014). MADS-box transcription factor SsMADS is involved in regulating growth and virulence in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 8049–8062. 10.3390/ijms15058049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauyaree P., Ospina-Giraldo M. D., Kang S., Bhat R. G., Subbarao K. V., Grant S. J., et al. (2005). Mutations in VMK1, a mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, affect microsclerotia formation and pathogenicity in Verticillium dahliae. Curr. Genet. 48, 109–116. 10.1007/s00294-005-0586-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E. S., Getz G., et al. (2011). Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Roldán C., Pareja-Jaime Y., González-Reyes J. A., Roncero M. I. (2015). The transcription factor Con7-1 is a master regulator of morphogenesis and virulence in Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28, 55–68. 10.1094/MPMI-07-14-0205-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A. I., Sharov V., White J., Li J., Liang W., Bhagabati N., et al. (2003). TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. BioTechniques 34, 374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz-Sommer Z., Huijser P., Nacken W., Saedler H., Sommer H. (1990). Genetic control of flower development by homeotic genes in Antirrhinum majus. Science 250, 931–936. 10.1126/science.250.4983.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servin J. A., Campbell A. J., Borkovich K. A. (2012). G protein signaling components in filamentous fungal genomes, in Biocommunication of Fungi, ed Witzany G. (Springer Netherlands; ), 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shore P., Sharrocks A. D. (1995). The MADS-box family of transcription factors. Eur. J. Biochem. 229, 1–13. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipanovic R. D., Bell A. A. (1976). Pentaketide metabolites of Verticillium dahliae. 3. Identification of (-)-3,4-dihydro-3,8-dihydroxy-1(2h)-naphtalenone((-)-vermelone) as a precursor to melanin. J. Org. Chem. 41, 2468–2469. 10.1021/jo00876a026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Ru Y., Hong L., Zhu Q., Zuo R., Guo X., et al. (2015). System-wide characterization of bZIP transcription factor proteins involved in infection-related morphogenesis of Magnaporthe oryzae. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 1377–1396. 10.1111/1462-2920.12618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Zhou L., Guo W., Wang X. (2015). Small GTPase Rac1 and its interaction partner Cla4 regulate polarized growth and pathogenicity in Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 74, 21–31. 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Xu J., Zhou L., Guo W. (2014). VdMsb regulates virulence and microsclerotia production in the fungal plant pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Gene 550, 238–244. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V. T., Braus-Stromeyer S. A., Kusch H., Reusche M., Kaever A., Kuhn A., et al. (2014). Verticillium transcription activator of adhesion Vta2 suppresses microsclerotia formation and is required for systemic infection of plant roots. New Phytol. 202, 565–581. 10.1111/nph.12671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzima A. K., Paplomatas E. J., Rauyaree P., Kang S. (2010). Roles of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in virulence and development of the soilborne plant pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47, 406–415. 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzima A. K., Paplomatas E. J., Tsitsigiannis D. I., Kang S. (2012). The G protein beta subunit controls virulence and multiple growth- and development-related traits in Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 49, 271–283. 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas W. A., Sanz-Martin J. M., Rech G. E., Armijos-Jaramillo V. D., Rivera L. P., Echeverria M. M., et al. (2015). A fungal effector with host nuclear localization and DNA-binding properties is required for maize anthracnose development. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 29, 83–95. 10.1094/MPMI-09-15-0209-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L., Xiao S. X., Xiong D. G., Tian C. M. (2013). Genetic transformation, infection process and qPCR quantification of Verticillium dahliae on smoke-tree Cotinus coggygria. Australas. Plant Path. 42, 33–41. 10.1007/s13313-012-0172-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tian L., Xiong D., Klosterman S. J., Xiao S., Tian C. (2016). The mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, VdHog1, regulates osmotic stress response, microsclerotia formation and virulence in Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 88, 13–23. 10.1016/j.fgb.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S. (1955). Longevity of the Verticillium wilt fungus in the laboratory and field. Phytopathology 45, 180–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne J., Treisman R. (1992). SRF and MCM1 have related but distinct DNA binding specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 3297–3303. 10.1093/nar/20.13.3297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C., Subbarao K., Schulbach K., Koike S. (1998). Effects of crop rotation and irrigation on Verticillium dahliae microsclerotia in soil and wilt in cauliflower. Phytopathology 88, 1046–1055. 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.10.1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D., Wang Y., Ma J., Klosterman S. J., Xiao S., Tian C. (2014). Deep mRNA sequencing reveals stage-specific transcriptome alterations during microsclerotia development in the smoke tree vascular wilt pathogen, Verticillium dahliae. BMC Genomics 15:324. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Liu H., Li G., Liu M., Yun Y., Wang C., et al. (2015). The MADS-box transcription factor FgMcm1 regulates cell identity and fungal development in Fusarium graminearum. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 2762–2776. 10.1111/1462-2920.12747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Liu W., Wang C., Xu Q., Wang Y., Ding S., et al. (2011). A MADS-box transcription factor MoMcm1 is required for male fertility, microconidium production and virulence in Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 33–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07556.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The strategy of gene replacement and validation of gene deletion mutants. (A) Gene replacement strategy for the deletion of VdMcm1. The split-marker method was used. The entire coding sequence of VdMcm1 was replaced with a geneticin resistance cassette. (B) Screen the geneticin resistance transformants by PCR with split-marker primers (5F: V1-F and Ge-R; 3F: Ge-F and V1-1R). (C) Validation of the VdMcm1 deletion mutants by PCR with primers M1-F and M1-R. The deletion mutants showed one band (the length of geneticin resistance cassette), the wild-type strain showed one different band (the length of VdMcm1) whereas the ectopic mutants contained two bands: one for the geneticin resistance cassette, one for VdMcm1. (D) Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed to validate the deletion and reintroduction of VdMcm1. (E) Confirmation of the VdMcm1 deletion mutant by Southern blot with a VdMcm1 probe. Genomic DNA of wild-type strain and VdMcm1 deletion mutant were digested with Kpn I.

Expression analysis of genes related to melanin biosynthesis. Calculation the transcript levels of five melanin biosynthesis genes with qRT-PCR. The β-tubulin gene was used as a reference gene for the expression analyses. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Scanning electron microscopy of smoke tree roots inoculated with conidial suspensions. Arrows show germinated conidia in the wild-type and complemented strains. The pictures were taken after 24 h of incubation with 106 conidia/ml.

Validation of mRNA-Seq expression patterns by qRT-PCR. The qRT-PCR results of the selected genes showed similar expression patterns to those detected by mRNA-Seq. VDAG_08640 and VDAG_08676 are bZIP transcription factor genes; VDAG_03208 is a C2H2 transcription factor gene; VDAG_00190 is a gene involved in melanin biosynthesis; VDAG_01206 is a pyruvate kinase gene which catalyzes the generation of pyruvate from phosphoenolpyruvate in glycolysis pahtway. The error bars represent standard deviations. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

VdMcm1 regulates genes expression of secondary metabolism gene clusters. (A) Line graph showing the expression pattern of secondary metabolism gene clusters in ΔVdMcm1-5 and wild-type strain. Log2(FPKM) value was used to draw the picture. (B) Heat map showed gene expression profiles of the gene clusters during microsclerotia development (Xiong et al., 2014). CO and GC represent conidia and conidial germination; MS1-MS4 represents four typical stages during the entire process of microsclerotia formation at 60, 72, 96 h, and 14 days.

A list of genes regulated by both VdMcm1 and Vta2.

A list of secreted protein-encoding genes significantly downregulated in ΔVdMcm1.

All the primers used in this study.