Abstract

Background: Cardiac arrhythmias represent a significant problem globally, leading to cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death. There is increasing evidence to suggest that increased oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species (ROS), which is elevated in conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, can lead to arrhythmogenesis.

Method: A literature review was undertaken to screen for articles that investigated the effects of ROS on cardiac ion channel function, remodeling and arrhythmogenesis.

Results: Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress is observed in heart failure, leading to increased production of ROS. Mitochondrial ROS, which is elevated in diabetes and hypertension, can stimulate its own production in a positive feedback loop, termed ROS-induced ROS release. Together with activation of mitochondrial inner membrane anion channels, it leads to mitochondrial depolarization. Abnormal function of these organelles can then activate downstream signaling pathways, ultimately culminating in altered function or expression of cardiac ion channels responsible for generating the cardiac action potential (AP). Vascular and cardiac endothelial cells become dysfunctional, leading to altered paracrine signaling to influence the electrophysiology of adjacent cardiomyocytes. All of these changes can in turn produce abnormalities in AP repolarization or conduction, thereby increasing likelihood of triggered activity and reentry.

Conclusion: ROS plays a significant role in producing arrhythmic substrate. Therapeutic strategies targeting upstream events include production of a strong reducing environment or the use of pharmacological agents that target organelle-specific proteins and ion channels. These may relieve oxidative stress and in turn prevent arrhythmic complications in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure.

Keywords: oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, conduction, repolarization, remodeling, arrhythmia

Introduction

Cardio-metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension place significant burdens on the healthcare system worldwide. Over the past decades, their prevalence has been steadily increasing, due to aging and a rising level of obesity in the population (Chan and Woo, 2010; Wong et al., 2011). These disorders are leading causes of mortality and morbidity, which are traditionally attributed to cardiovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Cardiac arrhythmias have increasingly been recognized as a cause of death. Diabetes may affect the prognosis of heart failure subjects differently at the clinical (Sardu et al., 2014b) and epigenetic level (Sardu et al., 2016). This article explores the normal functions of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria, and synthesize current experimental data to illustrate how increased oxidative and metabolic stress can lead to dysfunction of these organelles, and in turn can initiate signaling cascades that modify the ion channel function and promote electrophysiological and structural remodeling, which ultimately promotes arrhythmogenesis.

Normal functions of the endoplasmic reticulum, sarcoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria

The ER is the intracellular organelle responsible for protein synthesis, folding, maturation, and assembly before they are exported to the Golgi apparatus, cytosol and plasma membrane. The oxidative environment within the lumen ensures proper formation of tertiary and quaternary structures, aided by chaperones and abundance of Ca2+ for interactions between them. Abnormalities in these factors can lead to unfolding or misfolding of proteins, which in turn can accumulate within the ER lumen. This would produce ER stress and elicit the unfolded protein response (UPR), which serves to reduce protein synthesis, enhance protein folding ability and aid misfolded or unfolded protein to cellular degradation pathways (Tsang et al., 2010).

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of cardiomyocytes is responsible for excitation-contraction coupling and subsequent contractile activation. Thus, dihydropyridine receptors (DIHRs) are found in the transverse tubular system and have molecular configurations that are steeply voltage-dependent, enabling them to act as voltage sensors. They are allosterically coupled to RyRs, the Ca2+ release channels in the SR. A depolarizing wave from the plasma membrane can spread to the transverse tubules, thereby activating the DIHRs, which then allows RyRs to dissociate from DIHRs and release the luminal Ca2+, inducing further release from the SR by a mechanism called Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release. This intracellular Ca2+ is important for initiation of contractile activity, as it binds to Ca2+-sensitive proteins including troponin, myosin, and actin. Relaxation occurs when intracellular Ca2+ returns to normal levels by following mechanisms: passive efflux mediated by the electrogenic sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) out of the cell, active transport into the SR by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and passive diffusion into the mitochondria via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (Choi et al., 2014). Finally, the SR may have functions that are traditionally ascribed to the ER, such as protein synthesis and folding (Glembotski, 2012).

The mitochondria are the site of energy supply where ATP synthesis occurs by oxidative phosphorylation, with additional roles such as regulation of apoptosis, redox status and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Dikalov, 2011). ATP synthesis involves electron transfer through the respiratory chain from complex I through to complex IV, culminating in protons being pumped from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space (Chance and Williams, 1955). Mitochondria are the main source of ROS, which are derived mostly from complexes I and III, as well as enzymes such as the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and those involved in fatty acid beta-oxidation (St-Pierre et al., 2002; Starkov et al., 2004; Tahara et al., 2009; Brand, 2010). Oxygen free radical production is much more efficient by reverse electron transfer dependent on succinate (through complex I to NAD+) than forward electron transfer with NADH (Panov et al., 2007). This reverse electron transfer is an important mechanism of ROS production in many pathological conditions such as hypertension (Nazarewicz et al., 2013).

Increased oxidative stress and intracellular organelle dysfunction in cardio-metabolic disorders

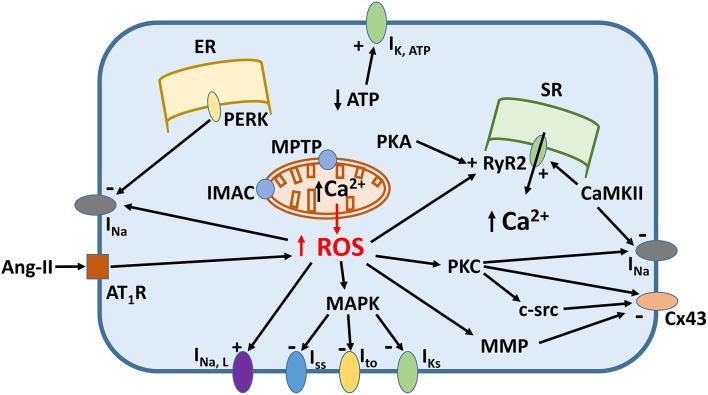

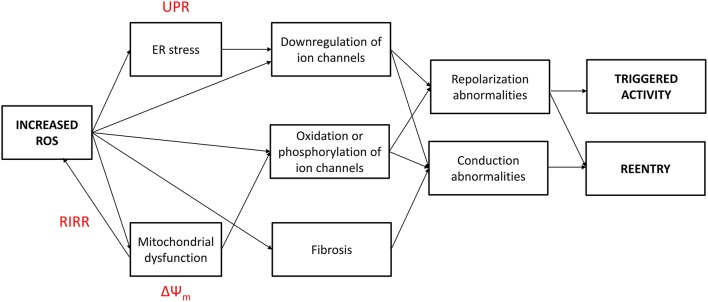

Increased oxidative stress from excessive ROS production appears to underlie pro-arrhythmic cardiac modeling in cardio-metabolic disorders (Figure 1). There is an increased arrhythmic burden, conditioning primary and secondary outcomes in patients with metabolic syndrome (Sardu et al., 2014a). ROS refers to superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrite, and hydroxyl radicals, which are unstable molecular species that can damage proteins and lipids within the cell, and activate intracellular signaling cascades. They can be generated by activation of NADPH oxidase or xanthine oxidase, uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) or leakage of electrons from the mitochondria during oxidative phosphorylation. Normally, cardiomyocytes are protected from ROS-mediated damage by several mechanisms. Firstly, enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase and glutathione peroxidase breakdown ROS into water and oxygen. Secondly, a series of redox defense systems can inactivate ROS, which are reduced glutathione (GSH), NADH, thioredoxin, and free radical scavengers such as vitamins C and E (Schafer and Buettner, 2001; Yamamoto et al., 2003; Zima et al., 2004; Gasparetto et al., 2005). Abnormal NADH accumulation, observed in diabetes, can lead to reductive stress, pseudohypoxia and subsequent, paradoxical oxidative stress; interested readers are directed to this article here (Yan, 2014). Increased oxidative stress is associated with abnormal function of intracellular organelles such as the ER and mitochondria (Wong et al., 2013; Cheang et al., 2014; Lenna et al., 2014; Murugan et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). Since both the ER and mitochondria are associated with Ca2+ release and uptake in cardiomyocytes and abnormal Ca2+ handling in these cells can cause arrhythmias, it is not surprisingly that ED could be the initial trigger. ROS can also promote structural and electrophysiological remodeling, leading to abnormalities in action potential (AP) conduction or repolarization (Tse and Yeo, 2015), and in turn to triggered activity or circus-type reentry (Figure 2). These mechanisms are considered in further detail below.

Figure 1.

Signaling mechanisms linking increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and ion channel remodeling.

Figure 2.

Increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in cardio-metabolic disorders induce both conduction and repolarization abnormalities, thereby leading to both triggered and reentrant arrhythmogenesis. UPR, unfolded protein response; RIRR, ROS-induced ROS release; ΔΨm, mitochondrial inner membrane potential.

Triggered activity and reentry can result from ROS generation

Action potential prolongation and abnormal Ca2+ handling can lead to triggered activity

Triggered activity results from afterdepolarizations, which are secondary depolarization events arising prematurely before generation of the next AP (Cranefield, 1977; January et al., 1991). They can occur before or after full repolarization, termed early afterdepolarizations (EADs) or delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs), respectively. EADs typically develop when action potential durations (APDs) are prolonged, due to a greater magnitude of inward depolarizing currents (INa, ICa, INCX) compared to the outward repolarizing currents (IKr, IKs, IK1) (Tse, 2015). This would enable reactivation of the L-type calcium channel, thereby increasing ICa, L (January and Riddle, 1989). By contrast, DADs occur when there is intracellular Ca2+ overload, which induces Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the ER. This activates the sodium-calcium exchange current, INCX, the nonselective cationic current, INS and the calcium-activated chloride current, ICl, Ca (Guinamard et al., 2004). The net result of EAD or DAD is membrane depolarization and initiation of another AP. If the afterdepolarizations are not sufficiently large to induce an AP, they can exacerbate the regional differences in repolarization, which may lead to alternans, unidirectional conduction block and reentry (Tse et al., in press).

Electrophysiological remodeling is observed in heart failure, with mostly downregulation of ion channels, leading to APD prolongation and/or altered calcium release, predisposing to EADs, DADs, and reentry (Marfella et al., 2013; Tse et al., 2016a). Moreover, the activities of ion channels may condition heart failure and arrhythmic state, regulating epigenetic mechanisms related to cardiac adaptive responses (Sardu et al., 2014c, 2015). The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) becomes activated in diabetes, hypertension and heart failure. This pathway is responsible for enzymatic cleavage of angiotensinogen, which is converted to angiotensin I and angiotensin II (Ang-II) by renin and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), respectively. Ang-II can activate the AT1 receptor, which increases NADPH oxidase activity to promote ROS production, resulting in downregulation of the calcium-independent transient outward K+ channel (Ito) (Lebeche et al., 2006). ROS can increase the activity of MAPK-activated protein kinase-1 (p90rsk), which phosphorylates and decreases the activity of Ito, f, IK, slow and ISS channels (Lu et al., 2008). ROS can prolongs the late sodium current, INa, L (Ma et al., 2005; Song Y. et al., 2006).

Moreover, prolonged activation of UPR during ER stress in heart failure leads to increased oxidative stress, downregulation of Ito and increased Ca2+ release from the SR. RyR2, the cardiac-specific isoform, is affected by post-translational modification from intracellular signaling cascades. Thus, they can be oxidized by ROS or reactive carbonyl species (RCS) (Eager et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1998; Bidasee et al., 2003), or phosphorylation by protein kinases such as protein kinase A or Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII), leading to abnormal gating (Witcher et al., 1991; Hain et al., 1995; Wehrens et al., 2004). This in turn leads to reduced amplitude but increased frequency of Ca2+ sparks and increased RyR2 sensitivity to Ca2+ activation (Shao et al., 2007, 2009). RyR2 decoupling from LTCCs can lead to desynchronized Ca2+ release (Song L.S. et al., 2006). ROS derived from the mitochondria could inhibit SERCA and stimulate RyR2, thereby activating NCX, Ca2+-sensitive cationic channels and Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release (Li et al., 2015).

Aside from regulation of energy production, mitochondria can also take up and release Ca2+ through several mechanisms, and may therefore serve as a buffer system. It may be that under physiological conditions, mitochondria do not have a major role in buffering Ca2+ (O'Rourke and Blatter, 2009; Williams et al., 2013). However, in heart failure, there is significant Ca2+ overload in both the cytoplasm and the mitochondria of cardiomyocytes (Santulli et al., 2015b). Experiments in a mouse model of heart failure generated by myocardial infarction, leaky RyR2 was shown to be responsible for mitochondrial Ca2+ overload (Santulli et al., 2015b). This would lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and increased ROS production. A recent study found that in mice with RyR2 mutations leading to diastolic Ca2+ leak, increased RyR2 oxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction and increased ROS production are observed, and these findings were associated with an increase in atrial fibrillation (AF) susceptibility (Xie et al., 2015a). Other studies also support the critical role of increased oxidative stress in the development and maintenance of AF. Thus, ROS from the atria correlated with the duration and substrate of AF in goats and humans (Reilly et al., 2011). Increased mitochondrial oxidative stress leading to RyR2 leak has also been observed in the ventricles of a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARg) cardiac overexpression mouse model (Joseph et al., 2016). The net electrophysiological effect was AP prolongation and development of ectopic activity.

Together, all of the above mechanisms can prolong APD and/or lead to abnormal Ca2+ release, inducing EADs and DADs and therefore triggered activity.

Disruption of normal AP conduction or repolarization and abnormal Ca2+ handling can lead to reentry

The conduction of cardiac APs through the working myocardium has traditionally been described by the core conductor model. This is based on the cable theory, whose equations can be derived by applying Kirchoff's circuit law. Conduction velocity (CV) is determined by both passive and active properties of the cell membrane. The passive components are axial resistance of the myoplasm (ri), resistance of the extracellular space (ro), and membrane capacitance (Cm). Diameter of the cardiomyocyte is important because it alters both ri and Cm. Active membrane properties refer to the voltage-gated conductances, mainly the sodium current (INa) mediating the AP upstroke. This model was subsequently modified to account for the presence of gap junctions (Saffitz et al., 1994; Rohr, 2004). Each gap junction consists of two connexons, which are hexameric proteins of the connexin (Cx) subunit, mediating electrical communication by electrotonic spread. However, it forms a high resistance pathway that can decrease CV and produce discontinuous propagation (Spach et al., 1981; Spach, 2003). Its expression is not equally distributed across the myocardium, higher numbers are found at the ends of myocytes compared to the lateral aspects of the cell membrane (Kumar and Gilula, 1996). Consequently, CV is higher in the longitudinal direction than in the transverse direction, which is termed anisotropic conduction (Sano et al., 1959; Clerc, 1976). The role of ephaptic coupling has been neglected until recently, involving a direct electrical field mechanism for mediating conduction (Rhett and Gourdie, 2012; Lin and Keener, 2013; Rhett et al., 2013; Veeraraghavan et al., 2014a,b,c; George et al., 2015; Veeraraghavan et al., 2015). Finally, myocardial fibrosis cam reduce the coupling between cardiomyocytes, increasing ri, and enhance the coupling between fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes (Camelliti et al., 2004; Chilton et al., 2007), increasing cm, both of which would reduce CV and increase the dispersion of CV (Tse and Yeo, 2015).

Circus-type reentry occurs when an AP travels around an obstacle and re-excites its site of origin, and requires both conduction and repolarization abnormalities (Tse, 2015; Tse et al., 2016d,h). Firstly, conduction velocity (CV) must be sufficiently slowed to prevent the AP depolarization wavefront from colliding with its repolarization wave back, where the local myocardium is still in its effective refractory period (ERP) and cannot be excited. If this occurs, conduction will be blocked and the AP will extinguish, resulting in a break of the reentrant circuit. Secondly, unidirectional conduction block must be present. Otherwise, wavefront APs traveling in opposite directions can collide and extinguish, thereby terminating the arrhythmia. Thirdly, an obstacle can be a non-conducting or refractory region, arising from structural defects such as interstitial fibrosis, or dynamically from ectopic activity. When the excitation wavelength of the AP wave (λ, CV × ERP) is smaller than the path length, reentry can occur. The ERP usually coincides with the APD. Thus, reduction in CV, APD, or ERP can promote reentry by reducing λ, whereas increased λ reduces the likelihood of reentry (Tse et al., 2012; Choy et al., 2016; Tse, 2016b; Tse et al., 2016c,e,f,g,h,i,k,l).

All of the above factors are influenced by ROS, altering ion channel function and promoting extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, which together would produce conduction and repolarization abnormalities, thereby leading to reentry (Tse and Yeo, 2015). For example, the SCN5A gene encoding for the cardiac Na+ channels is regulated by the transcription factor NF-κB (Shang and Dudley, 2005). Elevated angiotensin II levels and the increased oxidative stress increase NF-κB binding to the SCN5A promoter region, thereby decreasing its transcriptional activity (Shang et al., 2008). Ang-II can also downregulate Cx43 and Cx40, reducing intercellular coupling (Kasi et al., 2007). During ER stress, PERK activation downregulates the Na+ channels, although this is a non-ion channel specific effect since Ito expression is also reduced (Gao et al., 2013). Furthermore, abnormal Ca2+ release can have direct and indirect effects. Ca2+ can bind directly to the evolutionarily conserved EF hand motif at the carboxyl end of the Na+ channel, thereby producing a depolarizing shift in its voltage-dependent inactivation, which prolongs the late sodium current, INa, L (Wingo et al., 2004; Song Y. et al., 2006). Moreover, the Na+ channel also possesses an IQ domain for Ca2+/ CaM binding and additionally several serine/threonine residues amenable to phosphorylation, for example by CaMKII (Ashpole et al., 2012), leading to channel inactivation (Tan et al., 2002).

Ca2+ can activate protein kinase C (PKC) (Luo and Weinstein, 1993), which can phosphorylate both Na+ channels (Qu et al., 1996) and Cx43 (Moreno et al., 1994; Kwak et al., 1995) to reduce INa and Igap, respectively. Ca2+ overload is also associated with dephosphorylation of gap junctions (Huang et al., 1999), leading to their uncoupling (Beardslee et al., 2000) and lateralization (Smith et al., 1991; Lampe et al., 2000). Interestingly, a recent report demonstrated that streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice have increased phosphorylation levels of Cx43 at the serine 262 residue (Palatinus and Gourdie, 2016). Previous experiments showed that Ser 262 phosphorylation of Cx43 is associated with a cardiac injury-resistant state (Srisakuldee et al., 2009). Poor myocardial healing could increase the likelihood of conduction abnormalities, which would increase arrhythmogenicity. Finally, homocysteine, which is raised in hypertension and diabetes, causes EEC dysfunction and apoptosis (Miller et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2010), suppression of superoxide dismutase and activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the plasma membrane, causing Cx43 disruption (Rosenberger et al., 2006). Increased Ca2+ leak through the RyR2 channels results in Ca2+ alternans, which in turn can drive APD alternans and reentry (Xie et al., 2013).

Mitochondrial ROS production is elevated in diabetes and hypertension (Kakkar et al., 1995; Kanazawa et al., 2002; Dikalov and Ungvari, 2013). Mitochondrial ROS can itself increase its own production in a positive feedback loop, termed ROS-induced ROS release (RIRR), a mechanism recently recognized as a key initiator of mitochondrial depolarization (Zorov et al., 2000). Thus, Ang-II can activate the AT1 receptor, which stimulates Nox2, an enzyme that catalyzes electron transfer from NADPH to oxygen, generating oxygen free radicals and hydrogen peroxide. The oxygen free radical can enter the mitochondria and activate PKCε at the mitochondrial inner membrane (Jaburek et al., 2006). The downstream target is mitochondrial KATP channels (mitoKATP), resulting in reverse electron transfer from complex II to complex I, which generates more oxygen free radicals (Dikalov et al., 2014). The latter can be converted to hydrogen peroxide, activating c-src (Aikawa et al., 1997) and in turn further activating NADPH oxidases, production of free radicals and NOS uncoupling. Mitochondrial KATP channel activation in cardiomyocytes in diabetes led to impaired APD adaptation, which promoted the occurrence of VT (Xie et al., 2015b). Ang-II mediated mitochondrial ROS production can lead to c-src activation and reduced Cx43 expression (Sovari et al., 2013). Homocysteine can activate mitochondrial MMPs, which leads to opening the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) (Moshal et al., 2008; Montaigne et al., 2013) and collapse of the mitochondrial inner membrane potential (ΔΨm) (Brown et al., 2010).

ROS can also activate the mitochondrial inner membrane anion channels (IMAC) to result in mitochondrial depolarization (Yang et al., 2010). RIRR-induced regional mitochondrial depolarization results in the formation of a metabolic sink (Zhou et al., 2014). Uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation can reverse mitochondrial ATP synthase, thereby depleting intracellular ATP. This causes sarcolemmal KATP activation, increased K+ efflux and APD shortening (Garlid et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2014). Moreover, ROS can promote myocardial fibrosis via a NOX4-mediated, ROS-ERK1/2-MAP Kinase-dependent mechanism (Aragno et al., 2006; Kuroda et al., 2010).

Together, the above factors can lead to reduction in CV, together with increased repolarization gradients, can promote unidirectional conduction block and reentry (Tse et al., in press).

Endothelial-cardiomyocyte coupling, paracrine signaling, and arrhythmogenesis

Endothelial cells form the inner lining of blood vessels, thereby controlling vascular tone by releasing vasodilators, such as nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin and endothelial-dependent hyperpolarizing factor. In the heart, cardiac endothelial cells (CECs), including myocardial coronary endothelial cells (MCECs) lining the coronary microvasaculature and endocardial endothelial cells (EECs), outnumber cardiomyocytes (CM) with a 3:1 ratio and have roles distinct from those of the vascular endothelium, such as regulation of cardiomyocyte growth and modulation of electrical and mechanical functions (Baldwin and Artman, 1998; Brutsaert, 2003). They may do so in a paracrine manner by secreting messengers such as NO, prostaglandins, endothelin and angiotensin II. These may act on specific receptors on the plasma membrane of cardiomyocytes (e.g., Ang-II binding to AT1R), diffuse through the membrane of cardiomyocytes (in the case of gasotransmitters such as NO), or enter via gap junctions, to activate their downstream effector. Gap junctions are non-specific pores that also allows the spread of molecules up to 1 kDa in molecular mass (Harris, 2001; Weber et al., 2004). However, MCECs lack gap junctions and their communication with surrounding cells occur by other mechanisms.

Endothelial dysfunction is a hallmark of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and heart disease, playing a role in the initiation and progression of vascular dysfunction, eventually resulting in atherosclerosis, thrombosis and arrhythmogenesis (Wong et al., 2013). This usually refers to dysfunction of vascular endothelial cells that include the MCECs. However, EECs also become dysfunctional in diabetes and hypertension (Chu et al., 1995; Popov et al., 1996; Brutsaert, 2003). These could initiate signaling cascades that ultimately modify ion channel function and promote electrophysiological and structural remodeling in the myocardium to produce an arrhythmic substrate (Miller et al., 2002; Rosenberger et al., 2006; Moshal et al., 2008; Givvimani et al., 2011).

Clinical relevance and future perspectives

Reduction in oxidative stress is an attractive strategy for preventing ROS-induced ion channel dysfunction, electrophysiological and structural remodeling. In keeping with this theory, exogenous application of strong reducing agents such as hydrogen sulfide was shown to reduce cardiac fibrosis. Increasing the expression of enzymes breaking down free radicals, such as SOD (Dikalova et al., 2010). Glutathione peroxidase overexpression in diabetic rat hearts prevented adverse structural remodeling by reducing fibrosis and improving diastolic dysfunction (Matsushima et al., 2006). This would be expected to reduce the degree of conduction abnormalities and thereby increase the threshold for arrhythmogenesis.

Much of the cellular oxidative stress is derived from the mitochondria, which promotes arrhythmogenesis (Xie et al., 2015a). Therefore, antioxidants specifically targeting this organelle would be a logical strategy for anti-arrhythmic therapy. Thus, experiments in genetically modified, ACE8/8 mice with RAS activation have demonstrated therapeutic effects of a mitochondrial-specific antioxidant, but not a general antioxidant, in preventing ventricular arrhythmias (Sovari et al., 2013). Altered mitochondrial bioenergetics characterized by mitochondrial depolarization is a key initiating factor of an adverse positive feedback loop of causing RIRR. Interestingly, inhibition of the MPTP by cyclosporine A did not prevent the collapse of ΔΨm (Berkich et al., 2003), whereas IMAC inhibition using the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor did (Akar et al., 2005). Recent work has demonstrated that patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic VT, in whom the RyR2 is mutated and leaky, insulin secretion and glucose metabolism were dysregulated (Santulli et al., 2015a). Since mitochondrial Ca2+ overload is due to a leaky RyR2 (Santulli et al., 2015b), ryanodine receptor stabilizers can be used to reduce this leak and reduce arrhythmic burden (Lehnart et al., 2006). ER stress is also a potential target, since a prolonged UPR can induce adverse electrophysiological remodeling. For example, overexpression of chaperone proteins Grp78 and Grp94 can increase binding to UPR sensors and abnormal proteins, in turn alleviating ER and oxidative stress as well as Ca2+ overload (Vitadello et al., 2003; Pan et al., 2004).

Many of the above findings have been derived from animal models, which are amenable to genetic and pharmacological manipulation (Tse et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2016; Tse et al., 2016b,c,e,f,g,k, in press). In these systems, electrophysiological consequences of ion channel mutation or dysfunction can be examined using different recording methods such as monophasic action potential or bipolar electrogram recordings, and optical mapping (Vigmond and Bardakjian, 1995; Vigmond and Leon, 1999; Vigmond, 2005; Vigmond et al., 2009; Tse et al., 2016j). Furthermore, detection of magnetic signals has been used in clinical practice: for example magnetic resonance imaging is excellent for characterization of cardiac structures in humans but are less practical for use in animal studies (Vassiliou et al., 2014; Tse et al., 2015a,b). Magnetocardiography (MCG) can be used to diagnose and predict the risk of cardiac arrhythmias in humans (Steinhoff et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2012; Kwong et al., 2013; Ito et al., 2014; Yoshida et al., 2015). A micromagnetometer array with a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) can be used for non-contact recording of MCGs from mice and has the potential for high-throughput use to screen for pro- or anti-arrhythmic effects of pharmacological agents (Komamura et al., 2008). Given the evidence presented here, it is clear that increased ROS can lead to intracellular organelle dysfunction and arrhythmias in cardio-metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension. It is therefore prudent that the at-risk population is identified, which would enable early intervention to reduce arrhythmic mortality (Cardoso et al., 2003; Salles et al., 2005; Stettler et al., 2007; Clemente et al., 2012; Tse, 2016a,c; Tse and Yan, 2016a,b).

Nevertheless, because of the complex nature of cardiac spatiotemporal dynamics, a systems approach is needed to determine the net effect of a pharmacological agent on arrhythmogenicity. Identification of the molecular events is important for developing therapeutic strategies to reduce oxidative stress, which could slow or even reverse disease progression of cardio-metabolic disorders, which would in turn reduce the risk of cardiac arrhythmias complicating these conditions in this patient population.

Author contributions

GT: Design of manuscript; drafted and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; preparation of figures. BY: Interpreted primary research papers; critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. YC: Critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. XT and YH: Drafted and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer QY and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation, and the handling Editor states that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Acknowledgments

GT received a BBSRC Doctoral Training Award, and thanks the Croucher Foundation of Hong Kong for support of his clinical assistant professorship.

References

- Aikawa R., Komuro I., Yamazaki T., Zou Y., Kudoh S., Tanaka M., et al. (1997). Oxidative stress activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases through Src and Ras in cultured cardiac myocytes of neonatal rats. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 1813–1821. 10.1172/JCI119709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar F. G., Aon M. A., Tomaselli G. F., O'Rourke B. (2005). The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 3527–3535. 10.1172/JCI25371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragno M., Mastrocola R., Medana C., Catalano M. G., Vercellinatto I., Danni O., et al. (2006). Oxidative stress-dependent impairment of cardiac-specific transcription factors in experimental diabetes. Endocrinology 147, 5967–5974. 10.1210/en.2006-0728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashpole N. M., Herren A. W., Ginsburg K. S., Brogan J. D., Johnson D. E., Cummins T. R., et al. (2012). Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) regulates cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 gating by multiple phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 19856–19869. 10.1074/jbc.M111.322537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin H. S., Artman M. (1998). Recent advances in cardiovascular development: promise for the future. Cardiovasc. Res. 40, 456–468. 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00277-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee M. A., Lerner D. L., Tadros P. N., Laing J. G., Beyer E. C., Yamada K. A., et al. (2000). Dephosphorylation and intracellular redistribution of ventricular connexin43 during electrical uncoupling induced by ischemia. Circ. Res. 87, 656–662. 10.1161/01.RES.87.8.656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkich D. A., Salama G., LaNoue K. F. (2003). Mitochondrial membrane potentials in ischemic hearts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 420, 279–286. 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidasee K. R., Nallani K., Besch H. R., Jr., Dincer U. D. (2003). Streptozotocin-induced diabetes increases disulfide bond formation on cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305, 989–998. 10.1124/jpet.102.046201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M. D. (2010). The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol. 45, 466–472. 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. A., Aon M. A., Frasier C. R., Sloan R. C., Maloney A. H., Anderson E. J., et al. (2010). Cardiac arrhythmias induced by glutathione oxidation can be inhibited by preventing mitochondrial depolarization. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 673–679. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutsaert D. L. (2003). Cardiac endothelial-myocardial signaling: its role in cardiac growth, contractile performance, and rhythmicity. Physiol. Rev. 83, 59–115. 10.1152/physrev.00017.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camelliti P., Green C. R., LeGrice I., Kohl P. (2004). Fibroblast network in rabbit sinoatrial node: structural and functional identification of homogeneous and heterogeneous cell coupling. Circ. Res. 94, 828–835. 10.1161/01.RES.0000122382.19400.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso C. R., Salles G. F., Deccache W. (2003). Prognostic value of QT interval parameters in type 2 diabetes mellitus: results of a long-term follow-up prospective study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 17, 169–178. 10.1016/S1056-8727(02)00206-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R. S., Woo J. (2010). Prevention of overweight and obesity: how effective is the current public health approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7, 765–783. 10.3390/ijerph7030765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B., Williams G. R. (1955). Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. III. The steady state. J. Biol. Chem. 217, 409–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheang W. S., Tian X. Y., Wong W. T., Lau C. W., Lee S. S., Chen Z. Y., et al. (2014). Metformin protects endothelial function in diet-induced obese mice by inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress through 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 830–836. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Sun B., Tse G., Jiang J., Xu W. (2016). Reversibility of both sinus node dysfunction and reduced HCN4 mRNA expression level in an atrial tachycardia pacing model of tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome in rabbit hearts. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton L., Giles W. R., Smith G. L. (2007). Evidence of intercellular coupling between co-cultured adult rabbit ventricular myocytes and myofibroblasts. J. Physiol. 583, 225–236. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi E., Cha M. J., Hwang K. C. (2014). Roles of calcium regulating MicroRNAs in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cells 3, 899–913. 10.3390/cells3030899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy L., Yeo J. M., Tse V., Chan S. P., Tse G. (2016). Cardiac disease and arrhythmogenesis: lessons from mouse studies. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 12, 1–10. 10.1016/j.ijcha.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu G. X., Ling Q., Guo Z. G. (1995). Effects of endocardial endothelium in myocardial mechanics of hypertrophied myocardium of rats. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao 16, 352–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente D., Pereira T., Ribeiro S. (2012). Ventricular repolarization in diabetic patients: characterization and clinical implications. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 99, 1015–1022. 10.1590/S0066-782X2012005000095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc L. (1976). Directional differences of impulse spread in trabecular muscle from mammalian heart. J. Physiol. 255, 335–346. 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranefield P. F. (1977). Action potentials, afterpotentials, and arrhythmias. Circ. Res. 41, 415–423. 10.1161/01.RES.41.4.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalov S. (2011). Cross talk between mitochondria and NADPH oxidases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 1289–1301. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalov S. I., Nazarewicz R. R., Bikineyeva A., Hilenski L., Lassegue B., Griendling K. K., et al. (2014). Nox2-induced production of mitochondrial superoxide in angiotensin II-mediated endothelial oxidative stress and hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 20, 281–294. 10.1089/ars.2012.4918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalov S. I., Ungvari Z. (2013). Role of mitochondrial oxidative stress in hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 305, H1417–H1427. 10.1152/ajpheart.00089.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalova A. E., Bikineyeva A. T., Budzyn K., Nazarewicz R. R., McCann L., Lewis W., et al. (2010). Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial superoxide in hypertension. Circ. Res. 107, 106–116. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.214601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eager K. R., Roden L. D., Dulhunty A. F. (1997). Actions of sulfhydryl reagents on single ryanodine receptor Ca(2+)-release channels from sheep myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. 272, C1908–C1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G., Xie A., Zhang J., Herman A. M., Jeong E. M., Gu L., et al. (2013). Unfolded protein response regulates cardiac sodium current in systolic human heart failure. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 6, 1018–1024. 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlid K. D., Paucek P., Yarov-Yarovoy V., Murray H. N., Darbenzio R. B., D'Alonzo A. J., et al. (1997). Cardioprotective effect of diazoxide and its interaction with mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Possible mechanism of cardioprotection. Circ. Res. 81, 1072–1082. 10.1161/01.RES.81.6.1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparetto C., Malinverno A., Culacciati D., Gritti D., Prosperini P. G., Specchia G., et al. (2005). Antioxidant vitamins reduce oxidative stress and ventricular remodeling in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 18, 487–496. 10.1177/039463200501800308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S. A., Sciuto K. J., Lin J., Salama M. E., Keener J. P., Gourdie R. G., et al. (2015). Extracellular sodium and potassium levels modulate cardiac conduction in mice heterozygous null for the Connexin43 gene. Pflugers Arch. 467, 2287–2297. 10.1007/s00424-015-1698-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givvimani S., Qipshidze N., Tyagi N., Mishra P. K., Sen U., Tyagi S. C. (2011). Synergism between arrhythmia and hyperhomo-cysteinemia in structural heart disease. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 3, 107–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glembotski C. C. (2012). Roles for the sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum in cardiac myocyte contraction, protein synthesis, and protein quality control. Physiology 27, 343–350. 10.1152/physiol.00034.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinamard R., Chatelier A., Demion M., Potreau D., Patri S., Rahmati M., et al. (2004). Functional characterization of a Ca(2+)-activated non-selective cation channel in human atrial cardiomyocytes. J. Physiol. 558, 75–83. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hain J., Onoue H., Mayrleitner M., Fleischer S., Schindler H. (1995). Phosphorylation modulates the function of the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum from cardiac muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2074–2081. 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. L. (2001). Emerging issues of connexin channels: biophysics fills the gap. Q. Rev. Biophys. 34, 325–472. 10.1017/S0033583501003705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. D., Sandusky G. E., Zipes D. P. (1999). Heterogeneous loss of connexin43 protein in ischemic dog hearts. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 10, 79–91. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Shiga K., Yoshida K., Ogata K., Kandori A., Inaba T., et al. (2014). Development of a magnetocardiography-based algorithm for discrimination between ventricular arrhythmias originating from the right ventricular outflow tract and those originating from the aortic sinus cusp: a pilot study. Heart Rhythm. 11, 1605–1612. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaburek M., Costa A. D., Burton J. R., Costa C. L., Garlid K. D. (2006). Mitochondrial PKC epsilon and mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel copurify and coreconstitute to form a functioning signaling module in proteoliposomes. Circ. Res. 99, 878–883. 10.1161/01.RES.0000245106.80628.d3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January C. T., Chau V., Makielski J. C. (1991). Triggered activity in the heart: cellular mechanisms of early after-depolarizations. Eur. Heart J. 12, 4–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/12.suppl_F.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January C. T., Riddle J. M. (1989). Early afterdepolarizations: mechanism of induction and block. A role for L-type Ca2+ current. Circ. Res. 64, 977–990. 10.1161/01.RES.64.5.977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph L. C., Subramanyam P., Radlicz C., Trent C. M., Iyer V., Colecraft H. M., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial oxidative stress during cardiac lipid overload causes intracellular calcium leak and arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm.. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar R., Kalra J., Mantha S. V., Prasad K. (1995). Lipid peroxidation and activity of antioxidant enzymes in diabetic rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 151, 113–119. 10.1007/BF01322333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa A., Nishio Y., Kashiwagi A., Inagaki H., Kikkawa R., Horiike K. (2002). Reduced activity of mtTFA decreases the transcription in mitochondria isolated from diabetic rat heart. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 282, E778–E785. 10.1152/ajpendo.00255.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasi V. S., Xiao H. D., Shang L. L., Iravanian S., Langberg J., Witham E. A., et al. (2007). Cardiac-restricted angiotensin-converting enzyme overexpression causes conduction defects and connexin dysregulation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H182–H192. 10.1152/ajpheart.00684.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komamura K., Adachi Y., Miyamoto M., Kawai J., Haruta Y., Uehara G. (2008). Micro-Magnetocardiography system with a single-chip SQUID magnetometer array for QT analysis and diagnosis of myocardial injury in small animals. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2, 260–268. 10.1109/TBCAS.2008.2003979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N. M., Gilula N. B. (1996). The gap junction communication channel. Cell 84, 381–388. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81282-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda J., Ago T., Matsushima S., Zhai P., Schneider M. D., Sadoshima J. (2010). NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) is a major source of oxidative stress in the failing heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15565–15570. 10.1073/pnas.1002178107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak B. R., Hermans M. M., De Jonge H. R., Lohmann S. M., Jongsma H. J., Chanson M. (1995). Differential regulation of distinct types of gap junction channels by similar phosphorylating conditions. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 1707–1719. 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong J. S., Leithauser B., Park J. W., Yu C. M. (2013). Diagnostic value of magnetocardiography in coronary artery disease and cardiac arrhythmias: a review of clinical data. Int. J. Cardiol. 167, 1835–1842. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe P. D., TenBroek E. M., Burt J. M., Kurata W. E., Johnson R. G., Lau A. F. (2000). Phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368 by protein kinase C regulates gap junctional communication. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1503–1512. 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeche D., Kaprielian R., Hajjar R. (2006). Modulation of action potential duration on myocyte hypertrophic pathways. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 40, 725–735. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnart S. E., Terrenoire C., Reiken S., Wehrens X. H. T., Song L.-S., Tillman E. J., et al. (2006). Stabilization of cardiac ryanodine receptor prevents intracellular calcium leak and arrhythmias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7906–7910. 10.1073/pnas.0602133103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenna S., Han R., Trojanowska M. (2014). Endoplasmic reticulum stress and endothelial dysfunction. IUBMB Life 66, 530–537. 10.1002/iub.1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Su D., O'Rourke B., Pogwizd S. M., Zhou L. (2015). Mitochondria-derived ROS bursts disturb Ca2+ cycling and induce abnormal automaticity in guinea pig cardiomyocytes: a theoretical study. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 308, H623–H636. 10.1152/ajpheart.00493.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Keener J. P. (2013). Ephaptic coupling in cardiac myocytes. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 60, 576–582. 10.1109/TBME.2012.2226720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Abe J., Taunton J., Lu Y., Shishido T., McClain C., et al. (2008). Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase prolongs cardiac repolarization through inhibiting outward K+ channel activity. Circ. Res. 103, 269–278. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.166678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. H., Weinstein I. B. (1993). Calcium-dependent activation of protein kinase C. The role of the C2 domain in divalent cation selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 23580–23584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. H., Luo A. T., Zhang P. H. (2005). Effect of hydrogen peroxide on persistent sodium current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 26, 828–834. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00154.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfella R., Di Filippo C., Potenza N., Sardu C., Rizzo M. R., Siniscalchi M., et al. (2013). Circulating microRNA changes in heart failure patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy: responders vs. non-responders. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 15, 1277–1288. 10.1093/eurjhf/hft088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima S., Kinugawa S., Ide T., Matsusaka H., Inoue N., Ohta Y., et al. (2006). Overexpression of glutathione peroxidase attenuates myocardial remodeling and preserves diastolic function in diabetic heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H2237–H2245. 10.1152/ajpheart.00427.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A., Mujumdar V., Palmer L., Bower J. D., Tyagi S. C. (2002). Reversal of endocardial endothelial dysfunction by folic acid in homocysteinemic hypertensive rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 15, 157–163. 10.1016/S0895-7061(01)02286-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A., Mujumdar V., Shek E., Guillot J., Angelo M., Palmer L., et al. (2000). Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia induces multiorgan damage. Heart Vessels 15, 135–143. 10.1007/s003800070030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaigne D., Marechal X., Lefebvre P., Modine T., Fayad G., Dehondt H., et al. (2013). Mitochondrial dysfunction as an arrhythmogenic substrate: a translational proof-of-concept study in patients with metabolic syndrome in whom post-operative atrial fibrillation develops. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 1466–1473. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A. P., Saez J. C., Fishman G. I., Spray D. C. (1994). Human connexin43 gap junction channels. Regulation of unitary conductances by phosphorylation. Circ. Res. 74, 1050–1057. 10.1161/01.RES.74.6.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshal K. S., Metreveli N., Frank I., Tyagi S. C. (2008). Mitochondrial MMP activation, dysfunction and arrhythmogenesis in hyperhomocysteinemia. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 6, 84–92. 10.2174/157016108783955301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan D., Lau Y. S., Lau W. C., Mustafa M. R., Huang Y. (2015). Angiotensin 1-7 protects against angiotensin II-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and endothelial dysfunction via mas receptor. PLoS ONE 10:e0145413. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarewicz R. R., Dikalova A. E., Bikineyeva A., Dikalov S. I. (2013). Nox2 as a potential target of mitochondrial superoxide and its role in endothelial oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 305, H1131–H1140. 10.1152/ajpheart.00063.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke B., Blatter L. A. (2009). Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake: tortoise or hare? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 767–774. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatinus J. A., Gourdie R. G. (2016). Diabetes increases cryoinjury size with associated effects on Cx43 gap junction function and phosphorylation in the mouse heart. J. Diabetes Res. 2016:8789617. 10.1155/2016/8789617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y. X., Lin L., Ren A. J., Pan X. J., Chen H., Tang C. S., et al. (2004). HSP70 and GRP78 induced by endothelin-1 pretreatment enhance tolerance to hypoxia in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 44(Suppl. 1), S117–S120. 10.1097/01.fjc.0000166234.11336.a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panov A., Dikalov S., Shalbuyeva N., Hemendinger R., Greenamyre J. T., Rosenfeld J. (2007). Species- and tissue-specific relationships between mitochondrial permeability transition and generation of ROS in brain and liver mitochondria of rats and mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C708–C718. 10.1152/ajpcell.00202.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov D., Sima A., Stern D., Simionescu M. (1996). The pathomorphological alterations of endocardial endothelium in experimental diabetes and diabetes associated with hyperlipidemia. Acta Diabetol. 33, 41–47. 10.1007/BF00571939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y., Rogers J. C., Tanada T. N., Catterall W. A., Scheuer T. (1996). Phosphorylation of S1505 in the cardiac Na+ channel inactivation gate is required for modulation by protein kinase C. J. Gen. Physiol. 108, 375–379. 10.1085/jgp.108.5.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S. N., Jayaram R., Nahar K., Antoniades C., Verheule S., Channon K. M., et al. (2011). Atrial sources of reactive oxygen species vary with the duration and substrate of atrial fibrillation: implications for the antiarrhythmic effect of statins. Circulation 124, 1107–1117. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett J. M., Gourdie R. G. (2012). The perinexus: a new feature of Cx43 gap junction organization. Heart Rhythm. 9, 619–623. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett J. M., Veeraraghavan R., Poelzing S., Gourdie R. G. (2013). The perinexus: sign-post on the path to a new model of cardiac conduction? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 23, 222–228. 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr S. (2004). Role of gap junctions in the propagation of the cardiac action potential. Cardiovasc. Res. 62, 309–322. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger D., Moshal K. S., Kartha G. K., Tyagi N., Sen U., Lominadze D., et al. (2006). Arrhythmia and neuronal/endothelial myocyte uncoupling in hyperhomocysteinemia. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 112, 219–227. 10.1080/13813450601093443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffitz J. E., Kanter H. L., Green K. G., Tolley T. K., Beyer E. C. (1994). Tissue-specific determinants of anisotropic conduction velocity in canine atrial and ventricular myocardium. Circ. Res. 74, 1065–1070. 10.1161/01.RES.74.6.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles G. F., Deccache W., Cardoso C. R. (2005). Usefulness of QT-interval parameters for cardiovascular risk stratification in type 2 diabetic patients with arterial hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 19, 241–249. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano T., Takayama N., Shimamoto T. (1959). Directional difference of conduction velocity in the cardiac ventricular syncytium studied by microelectrodes. Circ. Res. 7, 262–267. 10.1161/01.RES.7.2.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli G., Pagano G., Sardu C., Xie W., Reiken S., D'Ascia S. L., et al. (2015a). Calcium release channel RyR2 regulates insulin release and glucose homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 1968–1978. 10.1172/JCI79273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli G., Xie W., Reiken S. R., Marks A. R. (2015b). Mitochondrial calcium overload is a key determinant in heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 11389–11394. 10.1073/pnas.1513047112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardu C., Barbieri M., Rizzo M. R., Paolisso P., Paolisso G., Marfella R. (2016). Cardiac resynchronization therapy outcomes in type 2 diabetic patients: role of microRNA changes. J. Diabetes Res. 2016:7292564. 10.1155/2016/7292564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardu C., Carreras G., Katsanos S., Kamperidis V., Pace M. C., Passavanti M. B., et al. (2014a). Metabolic syndrome is associated with a poor outcome in patients affected by outflow tract premature ventricular contractions treated by catheter ablation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 14:176. 10.1186/1471-2261-14-176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardu C., Marfella R., Santulli G. (2014b). Impact of diabetes mellitus on the clinical response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in elderly people. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 7, 362–368. 10.1007/s12265-014-9545-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardu C., Marfella R., Santulli G., Paolisso G. (2014c). Functional role of miRNA in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Pharmacogenomics 15, 1159–1168. 10.2217/pgs.14.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardu C., Santamaria M., Paolisso G., Marfella R. (2015). microRNA expression changes after atrial fibrillation catheter ablation. Pharmacogenomics 16, 1863–1877. 10.2217/pgs.15.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Yoshida K., Ogata K., Inaba T., Tada H., Sekiguchi Y., et al. (2012). An increase in right atrial magnetic strength is a novel predictor of recurrence of atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency catheter ablation. Circ. J. 76, 1601–1608. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer F. Q., Buettner G. R. (2001). Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30, 1191–1212. 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00480-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L. L., Dudley S. C., Jr. (2005). Tandem promoters and developmentally regulated 5′- and 3′-mRNA untranslated regions of the mouse Scn5a cardiac sodium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 933–940. 10.1074/jbc.M409977200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L. L., Sanyal S., Pfahnl A. E., Jiao Z., Allen J., Liu H., Dudley S. C., Jr. (2008). NF-kappaB-dependent transcriptional regulation of the cardiac scn5a sodium channel by angiotensin II. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C372–C379. 10.1152/ajpcell.00186.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C. H., Rozanski G. J., Patel K. P., Bidasee K. R. (2007). Dyssynchronous (non-uniform) Ca2+ release in myocytes from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 42, 234–246. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C.-H., Wehrens X. H. T., Wyatt T. A., Parbhu S., Rozanski G. J., Patel K. P., et al. (2009). Exercise training during diabetes attenuates cardiac ryanodine receptor dysregulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 106, 1280–1292. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91280.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. H., Green C. R., Peters N. S., Rothery S., Severs N. J. (1991). Altered patterns of gap junction distribution in ischemic heart disease. An immunohistochemical study of human myocardium using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Am. J. Pathol. 139, 801–821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L. S., Sobie E. A., McCulle S., Lederer W. J., Balke C. W., Cheng H. (2006). Orphaned ryanodine receptors in the failing heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4305–4310. 10.1073/pnas.0509324103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Shryock J. C., Wagner S., Maier L. S., Belardinelli L. (2006). Blocking late sodium current reduces hydrogen peroxide-induced arrhythmogenic activity and contractile dysfunction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 318, 214–222. 10.1124/jpet.106.101832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sovari A. A., Rutledge C. A., Jeong E. M., Dolmatova E., Arasu D., Liu H., et al. (2013). Mitochondria oxidative stress, connexin43 remodeling, and sudden arrhythmic death. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 6, 623–631. 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.976787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach M. S. (2003). Transition from a continuous to discontinuous understanding of cardiac conduction. Circ. Res. 92, 125–126. 10.1161/01.RES.0000056973.54305.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach M. S., Miller W. T., III., Geselowitz D. B., Barr R. C., Kootsey J. M., Johnson E. A. (1981). The discontinuous nature of propagation in normal canine cardiac muscle. Evidence for recurrent discontinuities of intracellular resistance that affect the membrane currents. Circ. Res. 48, 39–54. 10.1161/01.RES.48.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisakuldee W., Jeyaraman M. M., Nickel B. E., Tanguy S., Jiang Z. S., Kardami E. (2009). Phosphorylation of connexin-43 at serine 262 promotes a cardiac injury-resistant state. Cardiovasc. Res. 83, 672–681. 10.1093/cvr/cvp142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkov A. A., Fiskum G., Chinopoulos C., Lorenzo B. J., Browne S. E., Patel M. S., et al. (2004). Mitochondrial alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex generates reactive oxygen species. J. Neurosci. 24, 7779–7788. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff U., Knappe-Grueneberg S., Schnabel A., Trahms L., Smith F., Langley P., et al. (2004). Magnetocardiography for pharmacology safety studies requiring high patient throughput and reliability. J. Electrocardiol. 37(Suppl.), 187–192. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stettler C., Bearth A., Allemann S., Zwahlen M., Zanchin L., Deplazes M., et al. (2007). QTc interval and resting heart rate as long-term predictors of mortality in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 23-year follow-up. Diabetologia 50, 186–194. 10.1007/s00125-006-0483-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J., Buckingham J. A., Roebuck S. J., Brand M. D. (2002). Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44784–44790. 10.1074/jbc.M207217200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara E. B., Navarete F. D., Kowaltowski A. J. (2009). Tissue-, substrate-, and site-specific characteristics of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 1283–1297. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H. L., Kupershmidt S., Zhang R., Stepanovic S., Roden D. M., Wilde A. A., et al. (2002). A calcium sensor in the sodium channel modulates cardiac excitability. Nature 415, 442–447. 10.1038/415442a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang K. Y., Chan D., Bateman J. F., Cheah K. S. (2010). In vivo cellular adaptation to ER stress: survival strategies with double-edged consequences. J. Cell Sci. 123, 2145–2154. 10.1242/jcs.068833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G. (2015). Mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. J. Arrhythm. 32, 75–81. 10.1016/j.joa.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G. (2016a). Both transmural dispersion of repolarization and transmural dispersion of refractoriness are poor predictors of arrhythmogenicity: a role for the index of cardiac electrophysiological balance (QT/QRS)? J. Geriatr. Cardiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G. (2016b). Novel indices for stratifying arrhythmic risk: (Tpeak-Tend)/QRS and (Tpeak-Tend)/(QT x QRS). J. Geriatr. Cardiol. [Google Scholar]

- Tse G. (2016c). (Tpeak-Tend)/QRS and (Tpeak-Tend)/(QT x QRS): novel markers for predicting arrhythmic risk in Brugada syndrome. Europace. 10.17863/CAM.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Ali A., Alpendurada F., Prasad S., Raphael C. E., Vassiliou V. (2015a). Tuberculous constrictive pericarditis. Res. Cardiovasc. Med. 4:e29614. 10.5812/cardiovascmed.29614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Ali A., Prasad S. K., Vassiliou V., Raphael C. E. (2015b). Atypical case of post-partum cardiomyopathy: an overlap syndrome with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy? BJR|Case Rep. 1:20150182 10.1259/bjrcr.20150182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Hothi S. S., Grace A. A., Huang C. L. (2012). Ventricular arrhythmogenesis following slowed conduction in heptanol-treated, Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. J. Physiol. Sci. 62, 79–92. 10.1007/s12576-011-0187-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Lai E. T., Lee A. P., Yan B. P., Wong S. H. (2016a). Electrophysiological mechanisms of gastrointestinal arrhythmogenesis: lessons from the heart. Front. Physiol. 7:230. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Lai E. T., Tse V., Yeo J. M. (in press). Molecular electrophysiological mechanisms underlying cardiac arrhythmogenesis in diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Lai E. T., Yeo J. M., Yan B. P. (2016b). Electrophysiological mechanisms of Bayés syndrome: insights from clinical and mouse studies. Front. Physiol. 7:188. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Lai E. T., Yeo J. M., Yan B. P. (2016c). What is the arrhythmic substrate in viral myocarditis? Insights from clinical and animal studies. Front. Physiol. 7:308 10.3389/fphys.2016.00308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Lai T. H., Yeo J. M., Tse V., Wong S. H. (2016d). Mechanisms of electrical activation and conduction in the gastrointestinal system: lessons from cardiac electrophysiology. Front. Physiol. 7:182. 10.3389/fphys.2016.00182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Sun B., Wong S. T., Tse V., Yeo J. M. (2016e). Ventricular anti-arrhythmic effects of hypercalcaemia treatment in hyperkalaemic, Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. Biomed. Rep. 10.3892/br.2016.577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Tse V., Yeo J. M. (2016f). Ventricular anti arrhythmic effects of heptanol in hypokalaemic, Langendorff perfused mouse hearts. Biomed. Rep. 4, 313–324. 10.3892/br.2016.577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Tse V., Yeo J. M., Sun B. (2016g). Atrial anti-arrhythmic effects of heptanol in Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. PLoS ONE 11:e0148858. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Wong S. T., Tse V., Lee Y. T., Lin H. Y., Yeo J. M. (in press). Cardiac dynamics: alternans arrhythmogenesis. J Arrhythm. 10.1016/j.joa.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Wong S. T., Tse V., Yeo J. M. (2016h). Depolarization vs. repolarization: what is the mechanism of ventricular arrhythmogenesis underlying sodium channel haploinsufficiency in mouse hearts? Acta Physiol. (Oxf).. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/apha.12694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Wong S. T., Tse V., Yeo J. M. (2016i). Determination of action potential wavelength restitution in Scn5a+/− mouse hearts modelling human Brugada syndrome. J. Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Wong S. T., Tse V., Yeo J. M. (2016j). Monophasic action potential recordings: which is the recording electrode? J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol.. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1515/jbcpp-2016-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Wong S. T., Tse V., Yeo J. M. (2016k). Restitution analysis of alternans using dynamic pacing and its comparison with S1S2 restitution in heptanol-treated, hypokalaemic Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. Biomed. Rep. 4, 673–680. 10.3892/br.2016.659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Yan B. P. (2016a). Novel arrhythmic risk markers incorporating QRS dispersion: QRSd x (Tpeak-Tend) / QRS and QRSd x (Tpeak-Tend) / (QT x QRS). Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Yan B. P. (2016b). Traditional and novel electrocardiographic markers for predicting arrhythmic risk and sudden cardiac death. Europace. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Yeo J. M. (2015). Conduction abnormalities and ventricular arrhythmogenesis: the roles of sodium channels and gap junctions. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 9, 75–82. 10.1016/j.ijcha.2015.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse G., Yeo J. M., Tse V., Sun B. (2016l). Gap junction inhibition by heptanol increases ventricular arrhythmogenicity by decreasing conduction velocity without affecting repolarization properties or myocardial refractoriness in Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. Mol. Med. Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliou V., Chin C., Perperoglou A., Tse G., Ali A., Raphael C., et al. (2014). 93 Ejection fraction by cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts adverse outcomes post aortic valve replacement. Heart 100, A53–A54. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306118.93 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veeraraghavan R., Lin J., Hoeker G. S., Keener J. P., Gourdie R. G., Poelzing S. (2015). Sodium channels in the Cx43 gap junction perinexus may constitute a cardiac ephapse: an experimental and modeling study. Pflugers Arch. 467, 2093–2105. 10.1007/s00424-014-1675-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeraraghavan R., Poelzing S., Gourdie R. G. (2014a). Intercellular electrical communication in the heart: a new, active role for the intercalated disk. Cell Commun. Adhes. 21, 161–167. 10.3109/15419061.2014.905932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeraraghavan R., Poelzing S., Gourdie R. G. (2014b). Novel ligands for zipping and unzipping the intercalated disk: today's experimental tools, tomorrow's therapies? Cardiovasc. Res. 104, 229–230. 10.1093/cvr/cvu216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeraraghavan R., Poelzing S., Gourdie R. G. (2014c). Old cogs, new tricks: a scaffolding role for connexin43 and a junctional role for sodium channels? FEBS Lett. 588, 1244–1248. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigmond E. J. (2005). The electrophysiological basis of MAP recordings. Cardiovasc. Res. 68, 502–503. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigmond E. J., Bardakjian B. L. (1995). The effect of morphological interdigitation on field coupling between smooth muscle cells. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 42, 162–171. 10.1109/10.341829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigmond E. J., Leon L. J. (1999). Electrophysiological basis of mono-phasic action potential recordings. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 37, 359–365. 10.1007/BF02513313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigmond E. J., Tsoi V., Yin Y., Page P., Vinet A. (2009). Estimating atrial action potential duration from electrograms. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 56, 1546–1555. 10.1109/TBME.2009.2014740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitadello M., Penzo D., Petronilli V., Michieli G., Gomirato S., Menabo R., et al. (2003). Overexpression of the stress protein Grp94 reduces cardiomyocyte necrosis due to calcium overload and simulated ischemia. FASEB J. 17, 923–925. 10.1096/fj.02-0644fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber P. A., Chang H.-C., Spaeth K. E., Nitsche J. M., Nicholson B. J. (2004). The permeability of gap junction channels to probes of different size is dependent on connexin composition and permeant-pore affinities. Biophys. J. 87, 958–973. 10.1529/biophysj.103.036350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens X. H., Lehnart S. E., Reiken S. R., Marks A. R. (2004). Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ. Res. 94, e61–e70. 10.1161/01.RES.0000125626.33738.E2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H., Zhang R., Jin H., Liu D., Tang X., Tang C., et al. (2010). Hydrogen sulfide attenuates hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cardiomyocytic endoplasmic reticulum stress in rats. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1079–1091. 10.1089/ars.2009.2898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G. S., Boyman L., Chikando A. C., Khairallah R. J., Lederer W. J. (2013). Mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10479–10486. 10.1073/pnas.1300410110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo T. L., Shah V. N., Anderson M. E., Lybrand T. P., Chazin W. J., Balser J. R. (2004). An EF-hand in the sodium channel couples intracellular calcium to cardiac excitability. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 219–225. 10.1038/nsmb737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witcher D. R., Kovacs R. J., Schulman H., Cefali D. C., Jones L. R. (1991). Unique phosphorylation site on the cardiac ryanodine receptor regulates calcium channel activity. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 11144–11152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong E. L., Woo J., Hui E., Chan C., Chan W. L., Cheung A. W. (2011). Primary care for diabetes mellitus: perspective from older patients. Patient Prefer. Adherence 5, 491–498. 10.2147/PPA.S18687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W. T., Tian X. Y., Huang Y. (2013). Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes and hypertension: cross talk in RAS, BMP4, and ROS-dependent COX-2-derived prostanoids. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 61, 204–214. 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31827fe46e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Santulli G., Guo X., Gao M., Chen B. X., Marks A. R. (2013). Imaging atrial arrhythmic intracellular calcium in intact heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 64, 120–123. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Santulli G., Reiken S. R., Yuan Q., Osborne B. W., Chen B.-X., et al. (2015a). Mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes atrial fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 5:11427. 10.1038/srep11427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Liao Z., Grandi E., Shiferaw Y., Bers D. M. (2015b). Slow [Na]i changes and positive feedback between membrane potential and [Ca]i underlie intermittent early after depolarizations and arrhythmias. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 8, 1472–1480. 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Eu J. P., Meissner G., Stamler J. S. (1998). Activation of the cardiac calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) by poly-S-nitrosylation. Science 279, 234–237. 10.1126/science.279.5348.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Yang G., Hong C., Liu J., Holle E., Yu X., et al. (2003). Inhibition of endogenous thioredoxin in the heart increases oxidative stress and cardiac hypertrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1395–1406. 10.1172/JCI200317700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L.-J. (2014). Pathogenesis of chronic hyperglycemia: from reductive stress to oxidative stress. J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 11. 10.1155/2014/137919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Korge P., Weiss J. N., Qu Z. (2010). Mitochondrial oscillations and waves in cardiac myocytes: insights from computational models. Biophys. J. 98, 1428–1438. 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K., Ogata K., Inaba T., Nakazawa Y., Ito Y., Yamaguchi I., et al. (2015). Ability of magnetocardiography to detect regional dominant frequencies of atrial fibrillation. J. Arrhythm. 31, 345–351. 10.1016/j.joa.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu J., Luo J. Y., Tian X. Y., Cheang W. S., Xu J., et al. (2015). Upregulation of angiotensin (1-7)-mediated signaling preserves endothelial function through reducing oxidative stress in diabetes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 880–892. 10.1089/ars.2014.6070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Solhjoo S., Millare B., Plank G., Abraham M. R., Cortassa S., et al. (2014). Effects of regional mitochondrial depolarization on electrical propagation: implications for arrhythmogenesis. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 7, 143–151. 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zima A. V., Copello J. A., Blatter L. A. (2004). Effects of cytosolic NADH/NAD(+) levels on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) release in permeabilized rat ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 555, 727–741. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorov D. B., Filburn C. R., Klotz L. O., Zweier J. L., Sollott S. J. (2000). Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1001–1014. 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]