Abstract

Effective population size (Ne) is a central parameter in population and conservation genetics. It measures the magnitude of genetic drift, rates of accumulation of inbreeding in a population, and it conditions the efficacy of selection. It is often assumed that a single Ne can account for the evolution of genomes. However, recent work provides indirect evidence for heterogeneity in Ne throughout the genome. We study this by examining genome-wide diversity in the Danish Holstein cattle breed. Using the differences in allele frequencies over a single generation, we directly estimated Ne among autosomes and smaller windows within autosomes. We found statistically significant variation in Ne at both scales. However, no correlation was found between the detected regional variability in Ne, and proxies for the intensity of linked selection (local recombination rate, gene density), or the presence of either past strong selection or current artificial selection on traits of economic value. Our findings call for further caution regarding the wide applicability of the Ne concept for understanding quantitatively processes such as genetic drift and accumulation of consanguinity in both natural and managed populations.

Keywords: genetic drift, linked selection, effective population size, quantitative trait loci, Holstein breed

1. Introduction

The effective population size (Ne) measures the magnitude of genetic drift in a population. It determines expected levels of polymorphism, the efficacy of selection and the potential for accumulation of consanguinity in a population. Given its widespread use in population and conservation genetics, it is important to know whether a single Ne can account for the observed patterns of evolution in a population. Theory predicts that selection acting at linked sites can modulate the amount of genetic drift and hence the Ne experienced by a given site. The intensity of linked selection is expected to vary throughout the genome and thereby generate heterogeneity in Ne [1,2].

Empirical evidence for the heterogeneity of Ne has been indirect, relying almost exclusively on joint patterns of polymorphism and divergence [3]. It has been difficult to prove directly that Ne is heterogeneous throughout the genome and that heterogeneity observed in polymorphism is not merely reflecting variation in mutation rates [3,4].

Here, we use a method for directly estimating Ne based on temporal variation in allele frequencies. We test for heterogeneity of estimated Ne by genotyping a total of more than 1000 individuals representing three successive generations in a population from the Danish Holstein cattle breed. We find statistical evidence for substantial variation in Ne throughout the genome. We find that proxies commonly used for the expected intensity of linked selection cannot account for the variation observed.

2. Material and methods

(a). Sampling of individuals and genotyping

We studied the Danish Holstein population [5]. We selected three cohorts of individuals born in 1995, 2000 and 2005 (268, 295 and 579 individuals, respectively), genotyped using the 54 K SNP chip. Marker positions refer to the UMD3.1 assembly of the Bos taurus genome [6]. We only included SNPs with less than 10% missing data and genotyped in all cohorts, leaving a total of 46 268 SNPs. See the electronic supplementary material for further details.

(b). Estimation of Ne from temporal variation in allele frequency

For each autosome, SNPs were grouped in non-overlapping windows containing 100 SNPs (n = 447 windows). We used two Ne estimators based on the temporal variance in allele frequency, which have complementary statistical properties of variance and bias [7,8]. These estimators do not rely on pedigree information and provide direct estimates of Ne over a time interval in each window. We calculated the standard error (s.e.) of the Ne estimates within each window using 10 000 bootstrap samples (see the electronic supplementary material).

(c). Genomic covariates

For each window, we obtained data on the local recombination rate (centiMorgan per megabase), the density of genes (fraction of window in coding regions), the presence of quantitative trait loci (QTL) for three economically important traits selected in the population for the time period considered here (milk production, fat and protein content) and footprints of past selection in the Holstein breed (see the electronic supplementary material).

(d). Statistical analysis

We used linear models with Ne estimated in each window as the dependent variable, and genomic covariates, the chromosome of origin and physical length of each window as explanatory variables. Analyses were carried out in R [9] and are available as the electronic supplementary material. To account for the heterogeneity of standard errors around Ne estimates, models were fitted by weighted least squares using the function lm() and each window in the analysis was weighted by 1/s.e.

3. Results

We estimated Ne over one generation in two time intervals (1995–2000 and 2000–2005) and, unless stated otherwise, results reported here use the time interval 1995–2000 where roughly equal numbers of individuals were available. All results use estimator [8], as the alternative method [7] yielded similar Ne estimates (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

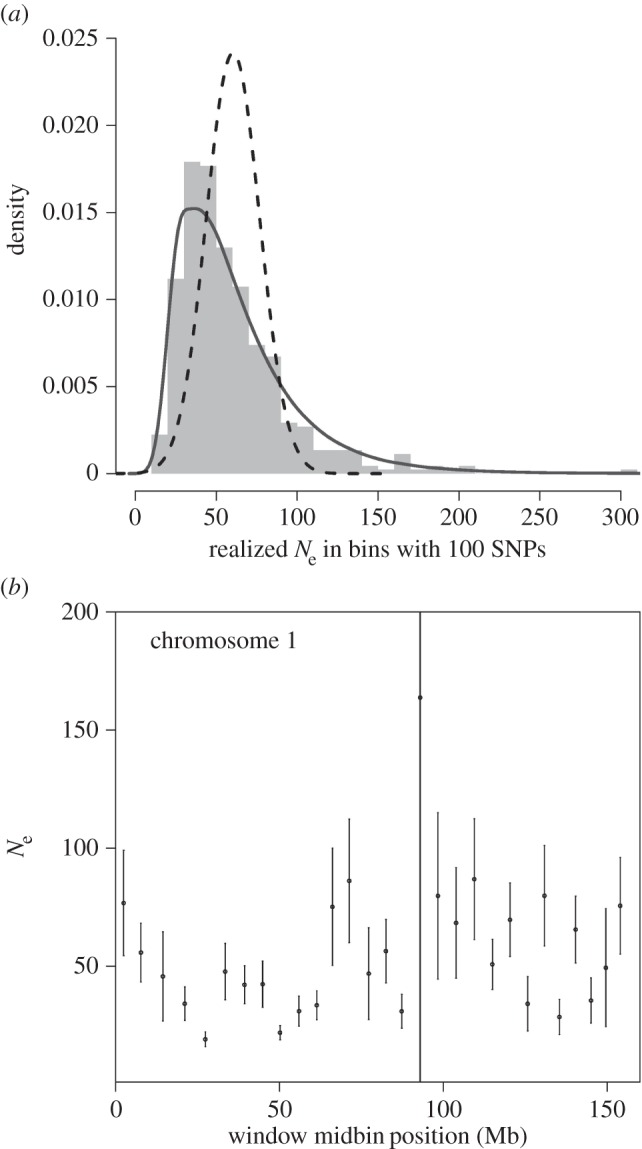

We found that the estimated Ne of each autosome varied by a factor of almost two (mean: 48, median: 45, min: 36 ± 2.6 on chromosome 25, max: 72 ± 6.4 on chromosome 23, electronic supplementary material, figure S1). We then estimated Ne within 447 autosomal windows of 100 SNPs, spanning on average 5 Mb (range: 3–10 Mb). This revealed considerable heterogeneity between windows in the estimated Ne (median: 50.83, s.d.: 37.4; figure 1a). Although some of the variation observed is due to sampling error, genuine variation remains among windows (p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Heterogeneity of estimated Ne in genomic windows. (a) Distribution of Ne over one generation (1995–2000) in 447 windows. Histogram: empirical distribution of Ne estimates. Dashed line: distribution expected under homogeneous Ne and incorporating standard errors on estimated Ne (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). Solid line: expected distribution for the estimated Ne under a model accounting for standard errors as above and further assuming lognormally distributed parametric variation in Ne among windows (see the electronic supplementary material). (b) Example of within-chromosome heterogeneity in estimated Ne. Each dot represents the Ne estimated per window. Errors bars indicate 1 s.e. (estimated by bootstrapping).

Genetic diversity is reduced in regions of low recombination rates and/or regions with high gene density [1,10], because they are expected to experience more background selection and are more likely to be affected by neighbouring selective sweeps. Therefore, we tested whether a number of genomic variables used as proxies for linked selection could explain the observed variation in estimated Ne. Although chromosome of origin significantly affected the estimated Ne of a window, neither local recombination rates nor gene density explained the variation in estimated Ne (table 1; electronic supplementary material, figures S2 and S3).

Table 1.

Effect of genomic covariates on log (Ne) in autosomal windows.

| explaining variables | estimatea | s.e.a | F-test | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chromosome | n.a. | n.a. | 3.56 | <0.00001 |

| physical window length | −3.31 × 10−8 | 2.006 × 10−8 | 1.09 | 0.297 |

| local gene density | −0.134 | 0.169 | 0.006 | 0.94 |

| local recombination | −0.087 | 0.049 | 3.49 | 0.06 |

| past selective sweeps | 0.0872 | 0.037 | 4.46 | 0.035 |

| number of QTLs | −0.0346 | 0.054 | 0.197 | 0.657 |

aEstimates of regression coefficients and associated standard errors are only provided for regressing/continuous explanatory variables.

bSignificance was tested using an F-test in a linear model accounting for heterogeneity of variance around Ne estimates.

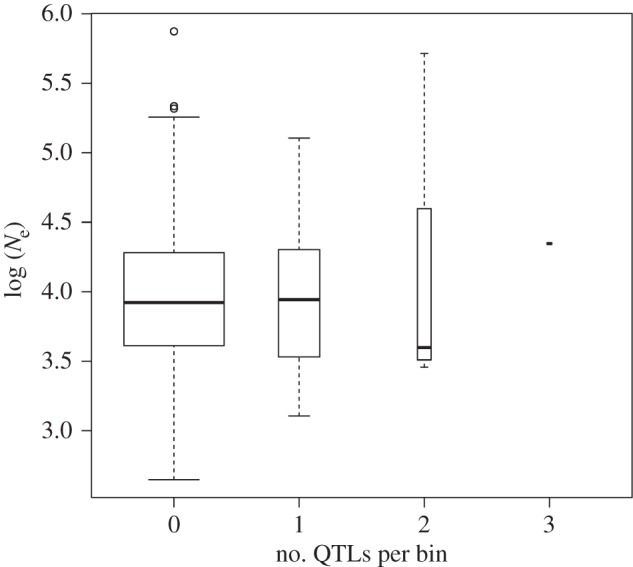

Episodes of strong natural or artificial selection are expected to affect the evolutionary trajectory of linked regions. Although a single Ne cannot rigorously account for the effect of directional selection on the diversity of neighbouring regions, we expect regions currently affected by a sweep to exhibit reduced estimated Ne. Using information on past selective sweeps in Holstein [11], we found no differences among Ne estimated in windows with no selective sweep (n = 378 windows) or 1, 2 or more than 2 selective sweeps (respectively n= 49, 13 and 7 windows; Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.56; electronic supplementary material, figure S4). We found an effect of the presence of past selective sweep but this effect is very small (table 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). We also used three traits of major economic value in the breed and currently under artificial selection in this population. No difference in estimated Ne among windows containing either no QTL (n = 375 windows) or QTLs for 1, 2 or 3 traits (respectively, n = 64, 7 and 1 windows) was found (Wilcoxon test, bins with QTL versus no QTL, p = 0.49; figure 2). Ne estimated in the vicinity of the 7 QTLs with the largest phenotypic effect was not markedly reduced relative to the remaining windows (p = 0.33; electronic supplementary material, table S1).

Figure 2.

Boxplot of log (Ne) among windows with either no QTL or harbouring QTLs coding for 1, 2 or 3 traits under artificial selection.

To guard against heterogeneity spuriously created by physical window size, we estimated Ne in 433 windows spanning 5 Mb (and thus variable number of SNPs). Irrespective of the window type used (fixed number of SNPs versus fixed length), we uncover very similar patterns of variation in estimated Ne and effect of chromosomes (electronic supplementary material, figure S6 and table S2). We still reveal significant heterogeneity among chromosomes (p < 0.0001) and no effect of other covariates.

We also estimated Ne over two generations (1995–2005) and found low correlations with estimates for the same window obtained for one-generation intervals (1995–2000 and 2000–2005). There was a weak and non-significant tendency for chromosomes with the highest Ne estimates in 1995–2000 to have the lowest Ne estimates in 2000–2005 (electronic supplementary material, figure S7).

4. Discussion

We provide direct evidence that the intensity of genetic drift varies throughout the genome. Our finding is robust to the choice of estimator for inferring Ne, potential effect of linkage decreasing effective sample size (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), time interval considered and type of window used (electronic supplementary material, figure S6). Overlapping generations and some non-random mating can bias Ne estimates based on temporal variance [12], but this bias will apply with equal forces throughout the genome and not create heterogeneity per se. Scale of analysis is ultimately limited by the sampling variance around Ne estimates and 100 SNPs per window was the minimum needed to get reliable Ne estimates.

Genome-wide average Ne estimated for the interval 1995–2000 (48) and for individual chromosomes (35–72; electronic supplementary material, figure S1) are within the range of values reported for this breed. Ne was estimated to be 49 for the Danish Holstein population for the period 1993–2003 using rates of inbreeding inferred from the pedigree [5]. Similarly, Ne for the US Holstein has been estimated to be 39 by the same method [13]. The magnitude of the heterogeneity we detected for Ne throughout the genome (figure 1a) was comparable, albeit in the lower range, of what was recently estimated indirectly in 10 species [3].

No effect of either local recombination rate, gene density or the presence of QTLs for traits under artificial selection was detected on estimated Ne (table 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Local recombination rates and gene density are commonly used proxies for the long-term effect of linked selection on nucleotide diversity throughout genomes [2,10,14]. We detect no correlation between these variables and the estimated Ne (table 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). One possibility is that recombination rates and gene density do affect the intensity of selection at linked sites, but at a scale of about 100 kb [14]. The windows we used were typically 50 times larger. Linked selection is also likely to act in an episodic fashion and most regions may not currently be experiencing linked selection. Another possibility is that the effect of linked selection acts cumulatively over timescales larger than the few generations examined here.

Interestingly, we detected no effect of the presence of QTL on estimated Ne over the 1995–2000 or 2000–2005 time intervals, but when estimating Ne over the 1995–2005 interval, we detect a modest effect of the presence of QTLs on Ne estimated in 5-Mb windows (electronic supplementary material, table S2). We expect that cumulative effects of selection on QTLs will be easier to detect in studies using longer time intervals. Summing up, although we present strong evidence for heterogeneity in Ne, the processes underlying this heterogeneity and that could account for the lack of correlation in Ne over successive generations (electronic supplementary material, figure S7) remain unknown.

5. Conclusion

Several studies report pervasive effects of selection throughout the genome of Drosophila [3,10,14]. A review on Ne and its applicability concludes: ‘ (…) no nucleotide in the compact genome of D. melanogaster is evolving entirely free of the effects of selection on its effective population size; it will be of great interest to see whether this applies to species with much larger genomes’ [1, p. 203]. Here, we provide direct evidence for extensive variation in Ne in a much less compact genome.

Ne plays a prominent role in conservation genetics to assess the status of populations, predict the rate of accumulation of consanguinity and forecast adverse consequences of inbreeding depression. If the variation in Ne we uncover is typical, caution should be used when interpreting mean values of Ne, as genomic regions can drift and accumulate consanguinity at a much higher rate than would be predicted if Ne was homogeneous (see [15] for a review in the topic).

Pervasive variation in Ne throughout the genome also raises concern for the uncritical use of genome-wide scans for footprints of selection. A popular strategy consists of deriving a null distribution for a test statistic, such as level of subdivision, length of homozygosity tracts, etc., expected under selective neutrality. Genomic regions exhibiting discrepant values for these statistics are then flagged as ‘candidates for selection’. However, null distributions for selective neutrality used so far rely on the implicit assumption that all regions undergo a common Ne. The true null distribution might actually contain substantially more variance than expected, and ignoring such variation will invariably yield inflated rates of false positives.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Thanks to B. Ehlers, S. Bailey, H. Siegismund, E. Wall, M. A. Toro and M. Lascoux for comments.

Data accessibility

Supporting data, metadata and R script are available as the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

B.J.M. and T.B. designed and wrote the study with input from all co-authors. B.G., R.B. and G.S. obtained SNP and analysed QTL data. B.J.M., P.T. and T.B. analysed SNP data. All authors agree to be held accountable for the content therein and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Funding

B.J.M. benefitted from a grant from Erasmus-Mundus PhD School ‘EGS-ABG’ and INRA Animal Genetics. The data for QTL are funded by the project ‘Genomic selection—from function to efficient utilization in cattle breeding’ (grant no. 3405-10-0137).

References

- 1.Charlesworth B. 2009. Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 195–205. ( 10.1038/nrg2526) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charlesworth B. 2012. The effects of deleterious mutations on evolution at linked sites. Genetics 190, 5–22. ( 10.1534/genetics.111.134288) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gossmann TI, Woolfit M, Eyre-Walker A. 2011. Quantifying the variation in the effective population size within a genome. Genetics 189, 1389–1402. ( 10.1534/genetics.111.132654) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orozco-terWengel P, Kapun M, Nolte V, Kofler R, Flatt T, Schloetterer C. 2012. Adaptation of Drosophila to a novel laboratory environment reveals temporally heterogeneous trajectories of selected alleles. Mol. Ecol. 21, 4931–4941. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05673.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sørensen AC, Sørensen MK, Berg P. 2005. Inbreeding in Danish dairy cattle breeds. J. Dairy Sci. 88, 1865–1872. ( 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72861-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimin AV et al. 2009. A whole-genome assembly of the domestic cow, Bos taurus. Genome Biol. 10, R42 ( 10.1186/gb-2009-10-4-r42) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waples RS. 1989. A generalized approach for estimating effective population size from temporal changes in allele frequency. Genetics 121, 379–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorde PE, Ryman N. 2007. Unbiased estimator for genetic drift and effective population size. Genetics 177, 927–935. ( 10.1534/genetics.107.075481) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ihaka R, Gentleman R. 1996. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5, 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright SI, Andolfatto P. 2008. The impact of natural selection on the genome: emerging patterns in Drosophila and Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 193–213. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173342) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu L, Bickhart DM, Cole JB, Schroeder SG, Song J, Van Tassell CP, Sonstegard TS, Liu GE. 2015. Genomic signatures reveal new evidences for selection of important traits in domestic cattle. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 711–725. ( 10.1093/molbev/msu333) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waples RS, Yokota M. 2007. Temporal estimates of effective population size in species with overlapping generations. Genetics 175, 219–233. ( 10.1534/genetics.106.065300) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weigel K. 2001. Controlling inbreeding in modern breeding programs. J. Dairy Sci. 84, E177–E184. ( 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)70213-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comeron JM. 2014. Background selection as baseline for nucleotide variation across the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004434 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004434) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiménez-Mena B, Hospital F, Bataillon T. 2016. Heterogeneity in effective population size and its implications in conservation genetics and animal breeding. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 8, 35–41. ( 10.1007/s12686-015-0508-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data, metadata and R script are available as the electronic supplementary material.