Abstract

Introduction

Extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) is relatively new surgical technique for low rectal cancers. It is a more radical approach than conventional abdominoperineal excision (APE) with potentially better oncological outcome. The aim of this study was to analyse short term results of ELAPE compared with conventional abdominoperineal excision.

Methods

Data were collected prospectively for 72 patients who underwent abdominoperineal excision (APE) for low rectal carcinomas from 2010 to 2014. Of these 24 patients underwent ELAPE with biological prosthetic mesh used to close the perineal defect.

Results

The median age of patients was 68 (37–87). Positive circumferential resection margin (1/24 vs. 8/48) and Intra operative perorations (0/24 vs. 6/48) compared favourably with ELAPE.

Conclusions

Short term results from this study support that ELAPE has better oncological outcome.

Keywords: ELAPE, Extralevator, Abdominoperineal excision, Rectal cancer

Highlights

-

•

Extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) is a relatively new surgical technique for low rectal cancers. It is a more radical approach than conventional abdominoperineal excision (APE) with potentially better oncological outcome.

-

•

Technical difficulty associated with operating deep in the pelvis through abdominal approach during conventional APE is overcome by extended perineal dissection in the prone Jack-knife position in ELAPE, therefore removing the anal canal, levators and low mesorectum altogether.

-

•

One advantage is en block removal of levator muscles creating more cylindrical specimen with better clearance thus reducing CRM involvement. The prone position gives the surgeon better visualization, hence reducing the chances of entering the wrong surgical plane and causing perforation.

-

•

Early reports suggest that ELAPE can improve patients' prognosis without a significant increase in morbidity with superior oncologic outcome as compared to standard techniques.

1. Introduction

Extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) is a relatively new surgical technique for low rectal cancers. Different studies have shown improved short term oncological outcomes compared to conventional abdominoperineal excision (APE) [1]. For low rectal cancers anterior resection (AR) is the preferred procedure. However, where sphincter preservation is not possible, abdominoperineal excision is performed. Overall prognosis of patients with APE is poor compared to those with anterior resection and local recurrence rates are also higher [2], [3], [4]. Positive circumferential resection margin and intraoperative perforation of tumour during APE are well known poor prognostic factors [5], [6], [7]. Total mesorectal excision (TME), chemo radiation and recently more radical surgical techniques like Extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) have been introduced to address these issues and to improve oncological outcome in low rectal cancers [4]. ELAPE involves total mesorectal excision up to coccyx and pelvic peritoneal dissection anterior to Denonvillier's fascia (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The abdomen is closed after leaving a posterior presacral swab and a pelvic tube drain. Then in prone jack knife position gluteus maximus and levators are divided laterally. Endopelvic fascia is divided and pelvic dissection is continued anterior to Denonvillier's fascia delivering a cylindrical specimen. The pelvic floor is then reconstructed with biological mesh.

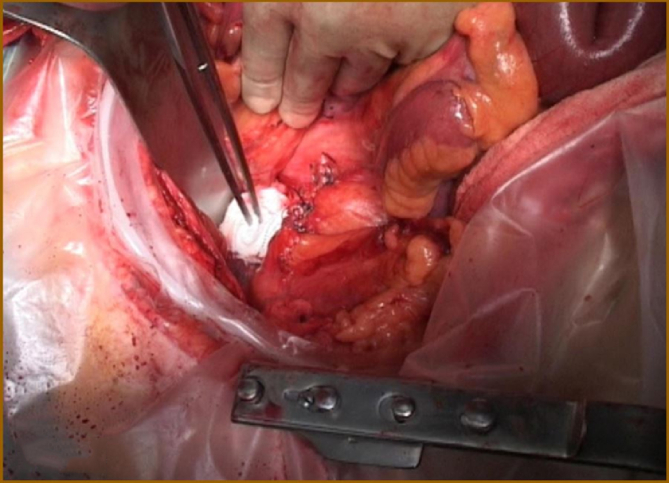

Fig. 1.

Abdominal dissection: TME to coccyx and pelvic peritoneal dissection anterior to Denonvillier's fascia.

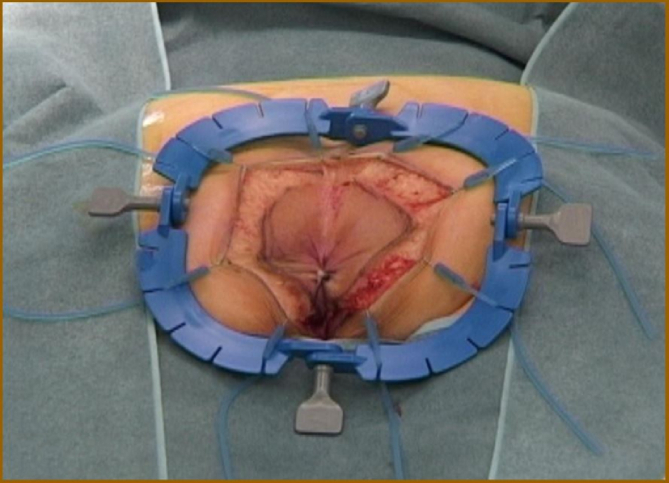

Fig. 2.

Tear drop incision.

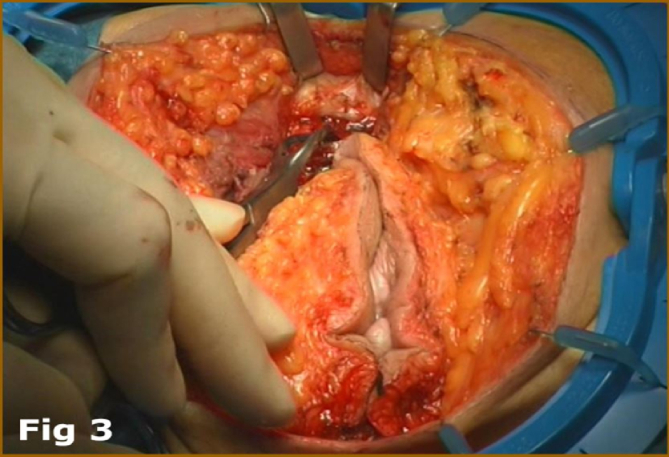

Fig. 3.

Dissection of ischeoanal fossa: Division of gluteus maximus and levators laterally and excision of coccyx.

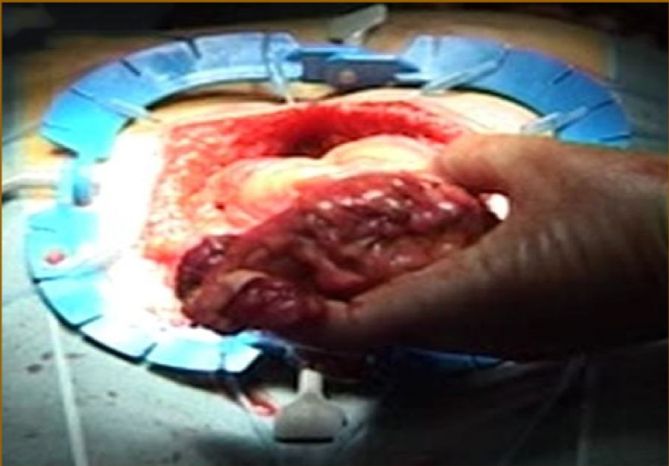

Fig. 4.

Delivery of rectum, cylindrical specimen.

The aim of this study was to analyse short-term results of ELAPE compared with conventional abdominoperineal excision in a district general hospital.

2. Methods

Hairmyres Hospital NHS Lanarkshire is a district General Hospital with a colorectal unit comprising four consultants. ELAPE technique has been practiced by two surgeons since 2010. Data was collected prospectively from all patients who underwent curative resection of low rectal carcinomas, whether APE or ELAPE, between 2010 and 2014. This gave a study population of 72 patients. Out of these 72 patients, 24 underwent ELAPE with biological prosthetic mesh used to close the perineal defect.

Indications for ELAPE were the same as for APE including tumour with direct invasion of the anal sphincter and distal rectal lesions in which it was impossible to achieve a safe distal margin with a sphincter sparing technique. Within the unit there was a gradual paradigm shift toward adopting ELAPE during the period of the study, while both procedures were being performed without any distinct selection strategy. All participants in the study gave their fully informed written consent.

Patients were followed-up for an average of 12 months post operatively. Variables recorded from patient notes are outlined in Table 1. In addition factors including: positive circumferential resection margin (positive CRM) in pathology reports, documented intra-operative perforations in operation notes, perineal wound dehiscence and evidence of local reoccurrence proven by CT and/or biopsies taken at endoscopy were also recorded (Table 2). No patients involved in the study were lost to follow-up. Operating surgeons were not involved in data collection or analysis and data collected was blinded to the surgeon performing each operation. Odds ratio, confidence interval and associated p values were calculated using MedCalc software and results reported in line with the STROBE criteria [8].

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics | ELAPE (n = 24) | APE (n = 48) |

|---|---|---|

| Age: median (range) | 68 (37–87) | 69 (41–82) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 15 (63%) | 33 (69%) |

| Female | 9 (38%) | 15 (31%) |

| BMI: median (range) | 25.7 (19.9–30.3) | 27.3 (22.5–33.3) |

| Median operation duration: median (range)in minutes | 320 (230–488) | 210 (150–360) |

| Blood loss in mls (median) | 200 ml | 500 ml |

| ASA classification | ||

| ASA I | 6 (25%) | 9 (19%) |

| ASA II | 18 (75%) | 39 (81%) |

| ASA III | 0 | 0 |

| ASA IV | 0 | 0 |

| Preoperative radiotherapy | 5 (20%) | 9 (19%) |

| TNM Staging | ||

| T1 | 9 (38%) | 15 (31%) |

| T2 | 12 (50%) | 27 (56%) |

| T3 | 3 (12%) | 6 (13%) |

| T4 | 0 | 0 |

| N0 | 18 (75%) | 31 (65%) |

| N1 | 6 (25%) | 14 (29%) |

| N2 | 0 | 3 (6%) |

| M0 | 24 (100%) | 48 (100%) |

| M1 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

Results ELAPE vs APE.

| ELAPE (n = 24) | APE (n = 48) | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive CRM | 1 | 8 | 0.31 | 0.081–1.22 | 0.094 |

| Intra operative perforations | 0 | 6 | 0.06 | 0.003–1.05 | 0.054 |

| Perineal wound dehiscence | 6 | 12 | 1.0 | 0.333–3.10 | 1.0 |

| Local recurrence | 1 | 6 | 0.188 | 0.022–1.58 | 0.124 |

3. Results

Patient characteristics including: age, ASA status and tumour stage were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). Positive circumferential resection margin (1/24 vs. 8/48) compared favourably with ELAPE (95% CI 0.081–1.22, P value: 0.094). Intra operative perforations were also much lower in ELAPE group (0/8 vs. 6/48), with P value 0.054, although 95% confidence interval (0.003–1.05) failed to prove significance of this finding. Perineal wound dehiscence occurred in 6/24 patients in ELAPE group vs. 12/48 patients in APE group. However, once again statistical significance of this finding could not be demonstrated (95% confidence interval 0.333–3.10, P value 1.0). Median follow up was 12 months (range 10–42 months). There was one local recurrence in ELAPE as compared to six in APE group (Table 2). Although this is an interesting finding once again this study was unable to prove statistical significance possibly due to the small sample size (95% confidence interval 0.22–1.58).

4. Discussion

Total mesorectal excision and chemo radiation have improved the oncological outcome of low rectal cancer [9], [10], [11]. This is reflected by long-term survival and lower local recurrence rates [9], [10], [11]. Recently more radical surgical approaches like extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) have been introduced with better results than conventional abdominoperineal excision (APE) [12], [13], [14]. This surgical treatment is more likely to achieve negative resection margins and avoid intra-operative tumour perforation [3], [4]. Technical difficulty associated with operating deep in the pelvis through abdominal approach during conventional APE is overcome by extended perineal dissection in the prone Jack-knife position in ELAPE, therefore removing the anal canal, levators and low mesorectum altogether. Advantage is en block removal of levator muscles creating more cylindrical specimen with better clearance thus reducing CRM involvement. Secondly, the prone position gives the surgeon better visualization, hence reducing the chances of entering the wrong surgical plane and causing perforation [15], [16]. Early reports suggest that the cylindrical method of excision can improve patients' prognosis without a significant increase in morbidity [17]. Stelzner et al. [18] suggested that ELAPE results in superior oncologic outcome as compared to standard techniques. The rates of bowel perforation and CRM involvement for ELAPE versus APE were significantly reduced [18]. Our early experience has shown similarities with these studies.

This study shows promising short-term results that are comparable with existing published data. However, there are a few studies that oppose these results, showing no difference in CRM involvement and bowel perforation between standard APE and ELAPE operation [19], [20]. This study, although important in the issues it raises, has limitations. The sample size is small, based in one centre, comparing the work of only two surgeons. There was no randomization between ELAPE and APE groups and no correction for other potential impacting variables on outcome such as ASA classification, socioeconomic status, and smoking status. Due to the relatively small number of patients in the ELAPE group, and the fact that these patients had relatively short duration of follow up due to relatively recent transition from conventional APE approach to ELAPE approach in our unit, we were unable to comment on long term survival benefit. Randomised controlled trials are required to confirm the true benefits of ELAPE.

Ethical approval

This was a case note review therefore no ethical approval sought.

Sources of funding

No funding.

Author contribution

Zilfiqar Hanif: study concept, design data analysis and interpretation, writing paper.

Alison Bradley: data interpretation, writing papaer.

Ahmed Hammad: data collection.

Arijit Mukherjee: study concept and design.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicting interests.

Guarantor

Mr. Zulfiqar Hanif.

Email: zulhan@hotmail.com.

Trial registry number

UIN number: 1084.

Consent

All patients involved gave their written consent prior to surgery.

Contributor Information

Zulfiqar Hanif, Email: zulhan@hotmail.com.

Alison Bradley, Email: bradley_alison@live.co.uk.

Ahmed Hammad, Email: ahammadfarrag@yahoo.com.

Arijit Mukherjee, Email: Arijit.mukherjee@lanarkshire.scot.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Mulsow J., Winter D.C. Extralevator abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer: new direction or miles behind? Arch. Surg. 2010;145:811–813. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heald R.J., Smedh R.K., Kald A. Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum – an endangered operation. Norman Nigro Lectureship. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1997;40:747–751. doi: 10.1007/BF02055425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksen M.T., Wibe A., Syse A. Inadvertent perforation during rectal cancer resection in Norway. Br. J. Surg. 2004;91:210–216. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagtegaal I.D., van de Velde C.J., Marijnen C.A. Low rectal cancer: a call for a change of approach in abdominoperineal resection. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:9,257–9,264. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrovic T., Breberina M., Radovanovic Z., Nikolic I., Ivkovic-Kapicl T., Vukadinovic Miucin I. The results of the surgical treatment of rectal cancer. Arch. Oncol. 2010;18:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksen M.T., Wibe A., Syse A., Haffner J., Wiig J.N. Inadvertent perforation during rectal cancer resection in Norway. Br. J. Surg. 2004;91:210–216. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wibe A., Syse A., Andersen E., Tretli S., Myrvold H.E., Soreide O. Oncological outcomes after total mesorectal excision for cure for cancer of the lower rectum: anterior vs. abdominoperineal resection. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2004;47:48–58. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Elm The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Intl J. Surg. 2014:1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heald R.J., Husband E.M., Ryall R.D. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479–1482. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enker W.E., Thaler H.T., Cranor M.L. Total mesorectal excision in the operative treatment of carcinoma of the rectum. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1995;181:335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aitken R.J. Mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 1996;83:214–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1996.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.W E.M. A Method of performing abdomino-perineal excision for carcinoma of the rectum and of the terminal portion of the pelvic colon. Lancet. 1908;172(4451):1812–1813. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.21.6.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holm T., Ljung A., Haggmark T., Jurell G., Lagergren J. Extended abdominoperineal resection with gluteus maximus flap reconstruction of the pelvic floor for rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2007 Feb;94(2):232–238. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West N.P., Finan P.J., Anderin C., Lindholm J., Holm T., Quirke P. Evidence of the oncologic superiority of cylindrical abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008 Jul 20;26(21):3517–3522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West N.P., Finan P.J., Anderin C., Lindholm J., Holm T., Quirke P. Evidence of the oncologic superiority of cylindrical abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;28(21):3517–3522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna A., Rickard M.J.F.X., Keshava A., Dent O.F., Chapuis P.H. A comparison of the published rates of resection margin involvement and intra-operative perforation between standard and ‘cylindrical’ abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shihab O.C., Heald R.J., Holm T., How P.D., Brown G., Quirke G. A pictorial description of extralevator abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stelzner S., Koehler C., Stelzer J., Sims A., Witzigmann H. Extended abdominoperineal excision vs. standard abdominoperineal excision in rectal cancer—a systematic overview. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(10):1227–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1235-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asplund D., Haglind E., Angenete E. Outcome of extralevator abdominoperineal excision compared with standard surgery: results from a single centre. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(10):1191–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Campos-Lobato L.F., Stocchi L., Dietz D.W., Lavery I.C., Fazio V.W., Kalady M.F. Prone or lithotomy positioning during an abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer results in comparable oncologic outcomes. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2011;54:939–946. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318221eb64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]