Abstract

Objective

To investigate the efficacy, safety, and microbiology of a thermosensitive otic suspension of ciprofloxacin (OTO-201) in children with bilateral middle ear effusion undergoing tympanostomy tube placement.

Study Design

Two randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled phase 3 trials. Patients were randomized to intratympanic OTO-201 or sham.

Setting

Children with bilateral middle ear effusion undergoing tympanostomy tube placement.

Subjects/Methods

Studies evaluated 532 patients (6 months to 17 years old) in a combined analysis of efficacy (treatment failure: presence of otorrhea, otic or systemic antibiotic use, lost to follow-up, missed visits), safety (audiometry, otoscopy, tympanometry), and microbiology.

Results

There was a lower cumulative proportion of treatment failures in patients receiving OTO-201 vs tympanostomy tubes alone (1) on days 4, 8, 15, and 29; (2) on day 15, primary end point (23.0% vs 45.1%; age-adjusted odds ratio, 0.341; P < .001; reduction in relative risk, 49%); and (3) on day 15, blinded-assessor otorrhea treatment failure (7.0% vs 19.4%; age-adjusted odds ratio, 0.303; P < .001; reduction in relative risk, 64%). Per-protocol and subgroup analyses (baseline demographics, pathogen type, culture status, effusion type, microbiologic response) supported these findings. There were no drug-related serious adverse events; the most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events in both groups were pyrexia, postoperative pain, nasopharyngitis, cough, and upper respiratory tract infection. OTO-201 administration had no evidence of increased tube occlusion and no negative effect on audiometry, tympanometry, or otoscopy.

Conclusions

Combined analysis of 2 phase 3 trials demonstrated a lower cumulative proportion of treatment failures through day 15 compared with TT alone when OTO-201 was administered intratympanically for otitis media with bilateral middle ear effusion at time of tympanostomy tube placement.

Keywords: middle ear effusion, otitis media, OTO-201, ciprofloxacin, tympanostomy tube, culture, otorrhea

Otitis media (OM) has a substantial health care burden.1,2 Tympanostomy tube placement (TTP) in children with recurrent acute OM or chronic OM with effusion is the most common pediatric ambulatory surgery in the United States.3 Otorrhea is an often-seen complication following TTP,4-6 affecting up to 25% of intubated ears.7 Otolaryngologists routinely apply antibiotic ear drops intraoperatively and prescribe them following surgery, although such medication is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this indication. Furthermore, delivery of ear drops into the middle ear cavity through a tympanostomy tube (TT) can be challenging.8

We report the integrated results of 2 phase 3 clinical trials evaluating the efficacy, safety, and microbiologic data of OTO-201 (OTIPRIO; Otonomy Inc, San Diego, California) in pediatric patients with OM with bilateral middle ear effusion (MEE) requiring TTP. In 2 identically designed phase 3 clinical trials, a suspension of ciprofloxacin microparticles in a buffered solution containing a thermosensitive polymer (poloxamer 407) was administered to pediatric patients with OM with bilateral MEE requiring TTP.9,10 OTO-201 exists as a liquid at or below room temperature and quickly transitions to a gel after exposure to body temperature in the middle ear. Preclinical studies have shown that a single injection of OTO-201 resulted in measureable ciprofloxacin concentrations in the middle ear for 1 to 2 weeks.11

Methods

Trial Designs

Evaluation of the efficacy, safety, and microbiologic data of OTO-201 in pediatric patients with bilateral MEE requiring TTP was based on integrated data from 2 identically designed phase 3 clinical trials consistent with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (sec 505 [21 USC §355], “New Drugs”). Trial 1 (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01949142) and trial 2 (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01949155) were conducted in compliance with the applicable regulatory requirements, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidance on Good Clinical Practice and per Institutional Review Board or Research Ethics Board approval. Inclusion criteria included pediatric patients aged 6 months to 17 years (inclusive) who were scheduled for TTP and who had otoscopically confirmed MEE on the day of surgery.

Randomization and Trial Intervention

Patients in both trials were randomized to receive intratympanic OTO-201 intraoperatively or sham (TT alone) through a 2:1 allocation ratio stratified by age (6 months to 2 years or >2 years), since younger children are considered more susceptible to the disease. Treatment assignment was generated via a permuted-block randomization algorithm; eligible patients were randomized on the day of surgery (day 1) prior to TTP. All external auditory canals and middle ears were liberally irrigated with saline prior to drug treatment and TTP. Other than the qualified medical professional who prepared the study drug and the surgeon administering treatment or TT alone, all persons involved in the trials (trial staff, caregivers, and patients) were blinded to treatment.

Key inclusion criteria required that patients were aged 6 months to 17 years of age, had a clinical diagnosis of bilateral MEE requiring TTP, and if of appropriate age, were able to provide assent for trial participation. For younger patients, the caregiver were willing to comply with the protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act documents before initiation of any trial-related procedures and provided written informed consent. Key exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) designation for any other concurrent surgery; (2) history of mastoid surgery, sensorineural hearing loss, chronic or recurrent bacterial infections (not including recurrent OM), tympanic membrane perforation, or known immunodeficiency disease; (3) abnormality of the tympanic membrane or middle ear; (4) topical nonsteroidal otic agents within 1 day of randomization; (5) topical or otic corticosteroid within 3 days of randomization or a systemic corticosteroid within 7 days of randomization; (6) topical or systemic antimicrobial or antifungal agents prior to approximate washout intervals; (7) concurrent use of oral anti-inflammatory agents; (8) history of allergy to ciprofloxacin or any of the components of OTO-201; and (9) menarcheal or postmenarcheal female.

An MEE culture specimen was tested at a central laboratory, and the remaining middle ear fluid was aspirated from each ear. Each 6-mg dose of OTO-201 (6%, 60 mg/mL [w/v] in poloxamer 407)—which was based on the results from a phase 1b clinical trial12—was given as a single 0.1-mL intratympanic administration into each ear, followed by TTP. For sham injections, the syringe was empty (TT alone). Patients visited the trial center on days 4, 8, 15, and 29 for safety, efficacy, and microbiologic assessments.

Trial Outcomes

Populations

An integrated database was constructed from data based on the 2 phase 3 trials. Planned sample size in each trial was 264 patients, which was derived via the methods described in the Statistical Analysis section and clinical experience from a phase 1b trial.12 Four analysis sets were used for the statistical analyses: (1) “safety analysis” consisted of all exposed patients who data were analyzed according to the actual treatment received of OTO-201 or TT alone; (2) “full analysis” for efficacy was the intent-to-treat set and consisted of all randomized patients whose data were analyzed according to the treatment group to which they were randomized; (3) “per protocol” was used as a sensitivity analysis of the primary efficacy end point and consisted of all patients without major protocol deviations (ie, excludes patients who had out-of-window/missed visits or were lost to follow-up) who had external otorrhea on ear examination at days 4, 8 and 15; and (4) “microbiologically evaluable” consisted of patients whose baseline bacteriology samples were positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis.

Efficacy assessments

The primary efficacy end point in both trials was assessed by the cumulative proportion of treatment failures (days 4-15), defined as one of the following, which ever occurred first: (1) otorrhea treatment failure—the presence of TT otorrhea in one or both ears, as noted by a blinded assessor (a medical professional who was not present during surgery nor involved in the preparation of the study drug) during the visual external ear examination on or after 3 days postsurgery (day 4); (2) otic treatment failure—patient received otic antibiotic drops any time postsurgery through day 15 prior to otorrhea confirmation by the blinded assessor; (3) systemic antibiotic treatment failure—patient received a systemic antibiotic any time postsurgery through day 15 prior to otorrhea confirmation by the blinded assessor; (4) loss to follow-up; or (5) missed visit treatment failure—patient not lost to follow-up who had a missing treatment failure status at a visit through day 15.

An effusion sample taken at the time of surgery was taken for microbiologic culture, sensitivity, and exploratory microbiologic testing. In addition to the otoscopic examination performed by the unblinded investigator, the assessment of TT otorrhea (a visual external ear examination) for the efficacy end point occurred on days 4, 8, 15, and 29 by the blinded assessor.

If the blinded assessor confirmed otorrhea in either ear on or after 3 days postsurgery (day 4), a specimen for culture was obtained, and the patient was eligible to receive ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone,13 4 drops twice a day in both ears for 7 days. All patients were asked to continue all trial assessments, regardless of otorrhea status, including continued assessment by the blinded assessor. Effusion type for each ear was categorized as absent, serous, purulent, sanguineous, or mucoid. Positive microbiology cultures were analyzed by the number of ears positive overall and the number of ears positive for each of the 5 organisms.

The cumulative proportion of treatment failures through day 15 was analyzed for the per-protocol population as a sensitivity analysis of the primary end point. Additional sensitivity analyses included the number and percentage of patients in the intent-to-treat population with treatment failures through day 15, summarized by subgroup according to sex, race, ethnicity, age stratum, baseline culture status, baseline effusion type and microbiology culture positivity.

Secondary efficacy end points included cumulative proportions of treatment failures (full analysis and per protocol), including by defined cause of treatment failure (full analysis), at days 4, 8, and 29; the cumulative proportion otorrhea-only treatment failures (ie, otorrhea as identified by the blinded assessor) at day 15; and microbiologic response at days 15 and 29 with presumption (patients with positive baseline cultures and without postbaseline cultures who were not treatment failures) or without presumption (patients with positive baseline cultures and negative postbaseline cultures).

Safety assessments

Safety assessments included treatment-emergent adverse events, otoscopy for presence of bilateral effusion, tube occlusion assessment, audiometric testing, tympanometry, physical examination, and vital sign measurement. Adverse events were classified with standard terminology (ie, system organ class and preferred term) according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 16.1).

Patients, if able, completed audiometric testing (typically ≥4 years of age) at screening and days 15 and 29; the audiologist determined the most appropriate test method (visual reinforcement audiometry, conditioned play audiometry, or conventional). The degree of hearing loss was calculated through the pure tone average (PTA; the sum of the threshold levels in decibels obtained for 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz, divided by the number of thresholds obtained) was used to calculate the degree of hearing loss and to categorize it as normal hearing (0-15 dB), slight hearing loss (16-25 dB), mild hearing loss (26-40 dB), moderate hearing loss (41-55 dB), moderate-severe hearing loss (56-70 dB), severe hearing loss (71-90 dB), and profound hearing loss (>90 dB). Shifts from screening in PTA for air conduction, bone conduction, and the air-bone gap—depicting shifts in air-bone gap ≤10 vs >10 dB—were calculated for each ear, each frequency, and each treatment group at each postbaseline measurement. Shifts were also noted from baseline to day 15 and to day 29 for the type of tympanogram (A, B [small/normal/large canal volume], or C), with ears as the unit of analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The cumulative proportion of treatment failures at each time point through day 29 was analyzed via the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, stratified by age (6 months to 2 years and >2 years), to determine whether the adjusted odds ratio (OR) was equal to 1.0 (ie, no association between treatment and outcome) at the 2-tailed 0.05 alpha level for the full analysis set. Estimates of the strength of association were provided with the adjusted relative risk (RR) and adjusted OR with associated 95% confidence intervals. The cumulative proportions presented were not adjusted for age.

Results

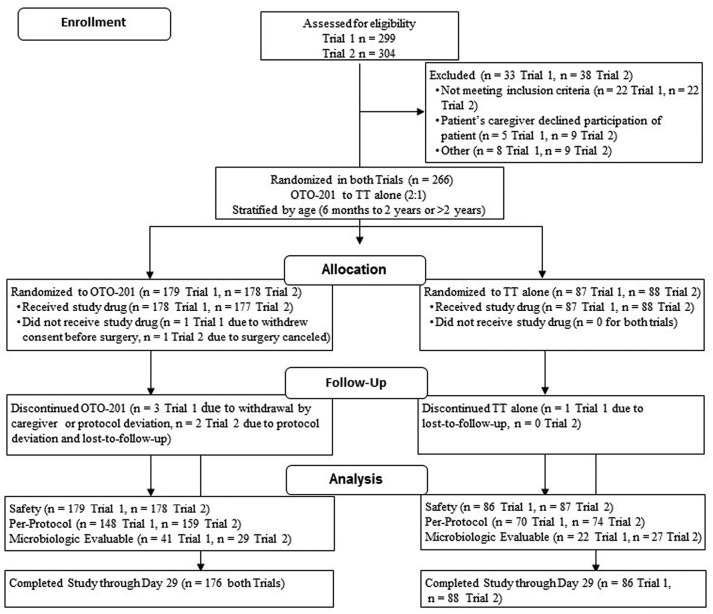

The integrated analysis included a total of 532 children with MEE requiring TTP who were randomized and participated in the trials between November 2013 and June 2014 ( Table 1 , Figure 1 ). Twenty-eight investigators conducted trial 1 (at 25 centers in the United States and 4 centers in Canada; 1 investigator was the principal investigator at 2 centers); 19 investigators conducted trial 2 (at 18 centers in the United States and 1 center in Canada).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Disease Characteristics.a

| Characteristic | OTO-201 (n = 357) | TT Alone (n = 175) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 2.336 ± 1.986 | 2.664 ± 2.371 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 200 (56.0) | 104 (59.4) |

| Female | 157 (44.0) | 71 (40.6) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 40 (11.2) | 21 (12.0) |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 311 (87.1) | 145 (82.9) |

| Not reported | 2 (0.6) | 4 (2.3) |

| Unknown | 4 (1.1) | 5 (2.9) |

| Race | ||

| White | 288 (80.7) | 141 (80.6) |

| Black or African American | 43 (12.0) | 23 (13.1) |

| Asian | 4 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Native American / Canadian | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Not applicable | 2 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) |

| Other | 16 (4.5) | 5 (2.9) |

| At least 1 ear, effusion type | ||

| Absentb | 5 (1.4) | 1 (0.6) |

| Mucoid | 202 (56.6) | 103 (58.9) |

| Purulent | 49 (13.7) | 21 (12.0) |

| Sanguineous | 1 (0.3) | 4 (2.3) |

| Serous | 145 (40.6) | 67 (38.3) |

| Positive microbiology culturec | ||

| One ear | 46 (12.9) | 32 (18.3) |

| Both ears | 24 (6.7) | 17 (9.7) |

| At least 1 ear | 70 (19.6) | 49 (28.0) |

| Positive baseline microbiology culture, at least 1 eard | ||

| H influenza | 39 (10.9) | 27 (15.4) |

| M catarrhalis | 14 (3.9) | 8 (4.6) |

| P aeruginosa | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.1) |

| S pneumonia | 20 (5.6) | 12 (6.9) |

| S aureus | 6 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) |

Values are presented as n (%) unless noted otherwise. Percentages are based on the number of patients in a given treatment group for the population analyzed. Baseline is defined as the last measurement taken on or prior to the day of randomization.

Effusion marked absent indicates that the type of effusion was not recorded.

“At least 1 ear” includes “one ear” and “both ears.”

Determination of whether baseline microbiology culture was positive for at least 1 of the following 5 organisms: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for the trials. Patients excluded following eligibility assessment may have been excluded for multiple reasons. TT, tympanostomy tube.

Patients and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 266 patients were randomized in each trial (179 and 178 patients to the OTO-201 dose groups and 87 and 88 patients to the TT-alone groups in trials 1 and 2, respectively; Figure 1 ). Baseline demographics were generally balanced across all groups ( Table 1 ). The majority of patients were between 6 months and 2 years (61.3%).

Efficacy

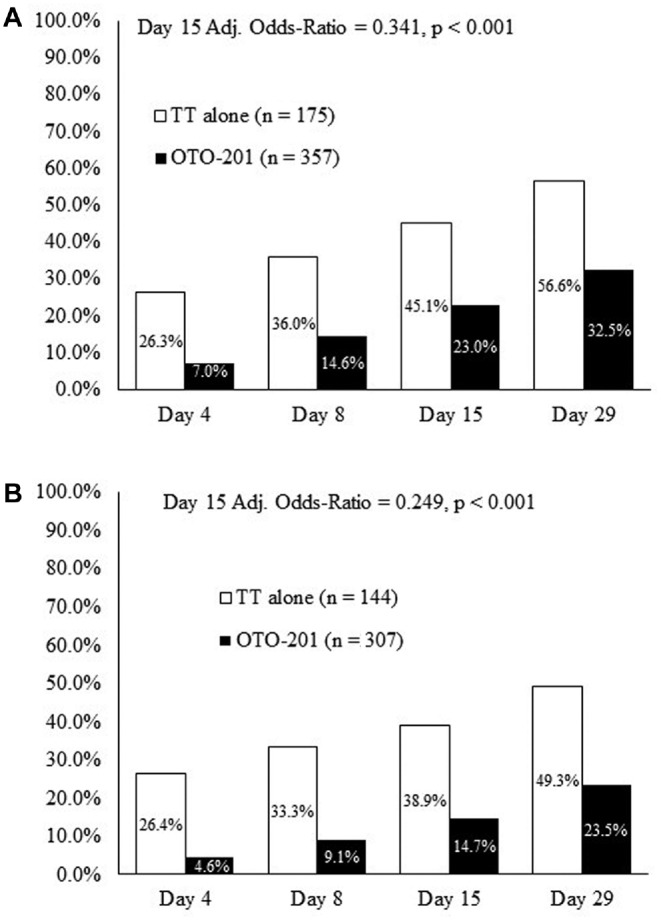

In this integrated analysis, the cumulative proportions of treatment failures in the intent-to-treat population at days 4, 8, 15, and 29 were lower in the OTO-201 group than the TT-alone group. By day 15 (primary end point), 23.0% of patients receiving OTO-201 experienced treatment failure, as compared with 45.1% of patients in the TT-alone group (age-adjusted OR, 0.341; P < .001; RR, 0.506; Figure 2A ), reflecting a 49% reduction in treatment failure risk for OTO-201 patients relative to those receiving TT alone. Day 15 per-protocol population provided strong support for the primary analysis (day 15: OTO-201 vs TT alone, 14.7% vs 38.9%; age-adjusted OR, 0.249; P < .001; RR, 0.377; Figure 2B ), reflecting a 62% reduction in treatment failure risk for patients who received OTO-201 relative to TT alone.

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of treatment failures at day 15 (patients, %). (a) Intent-to-treat population (day 15, primary end point; days 4, 8, and 29, secondary efficacy end points). (b) Per-protocol population (sensitivity analysis). TT, tympanostomy tube.

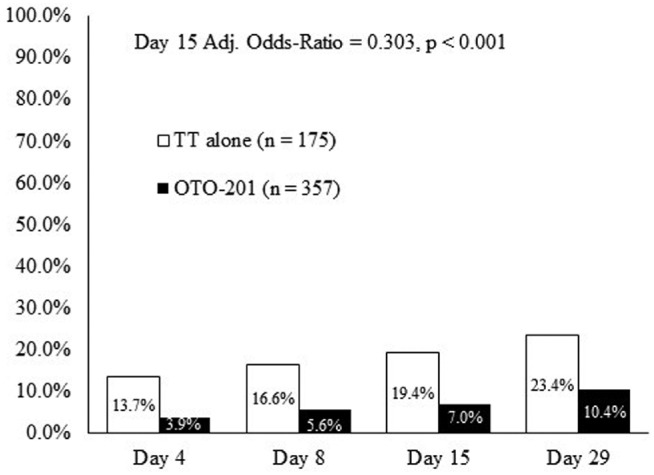

The cumulative proportion of otorrhea-only treatment failures, as documented by the blinded assessor during the external ear examination, was lower in patients who received OTO-201 than those who received TT alone starting at day 4 and at all visits through day 29. At day 15, the OTO-201 otorrhea treatment failure (per the blinded assessor) was 7.0%, compared with 19.4% for TT alone (age-adjusted OR, 0.303; P < .001; RR, 0.358), reflecting a 64% reduction in treatment failure risk due to otorrhea for OTO-201 patients relative to those receiving TT alone ( Figure 3 ). Analysis within each age stratum in both trials revealed a stronger treatment effect of OTO-201 in younger patients (6 months to 2 years) than in older patients (>2 years).

Figure 3.

Cumulative proportion of treatment failures due to otorrhea (per blinded assessor) from day 4 through day 29 (patients, %). Intent-to-treat population (day 15, secondary end point; days 4, 8, and 29, sensitivity analysis). TT, tympanostomy tube.

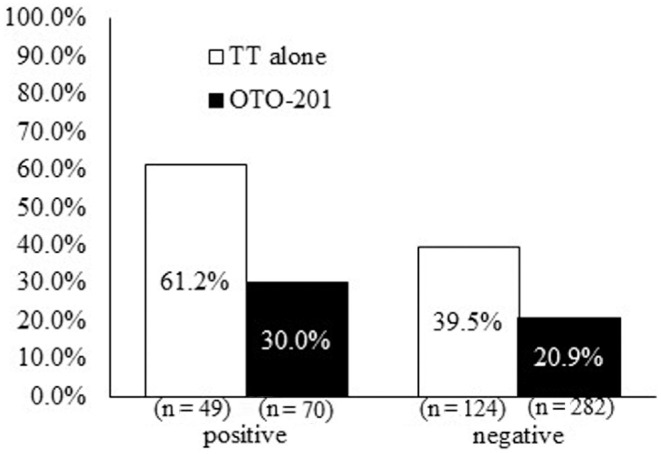

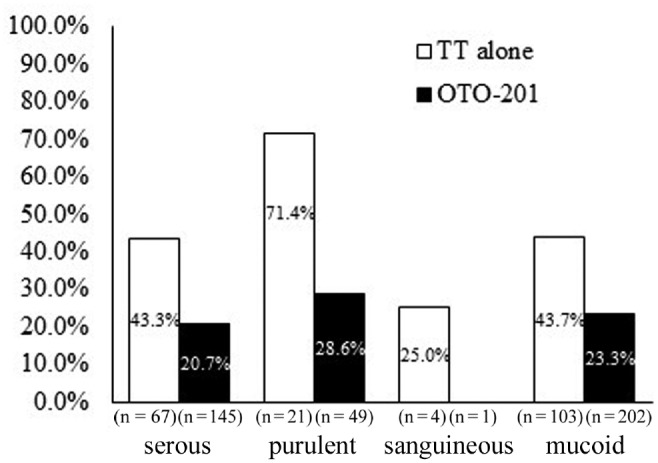

The primary end point (day 15 treatment failure) was supported by subpopulation analyses, where lower treatment failures in the OTO-201 group were seen in the analysis by baseline culture status (positive or negative; Figure 4 ) and baseline effusion type ( Figure 5 ; sanguineous effusion had too few events to make any meaningful conclusion). Microbiologic response (total, with and without presumption; see Figure S1 at www.otojournal.org/supplemental) was higher in patients who received OTO-201 versus those who received TT alone. There were not enough patients in the subgroups positive at baseline with the 5 main otic pathogens to make any meaningful comparisons.

Figure 4.

Cumulative proportion of treatment failures through day 15 as a function of baseline culture status (intent to treat, sensitivity analysis). TT, tympanostomy tube.

Figure 5.

Cumulative proportion of treatment failures through day 15 as a function of baseline effusion type (intent to treat, sensitivity analysis). TT, tympanostomy tube.

Safety

In both trials, there were no serious or life-threatening adverse events related to the study drug and no treatment-emergent adverse events resulting in patient discontinuation from either trial. Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. The most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events for both groups combined were pyrexia, procedural (postoperative) pain, nasopharyngitis, cough, and upper respiratory tract infection ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events with >2% Total Incidence by Treatment Group and Preferred Term: Safety Analysis Population.a

| Preferred Term | OTO-201 (n = 357) | TT Alone (n = 173) |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients with at least 1 TEAE reported | 189 (52.9) | 95 (54.9) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 23 (6.4) | 12 (6.9) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 18 (5.0) | 6 (3.5) |

| Pyrexia | 40 (11.2) | 20 (11.6) |

| Irritability | 17 (4.8) | 5 (2.9) |

| Vomiting | 11 (3.1) | 5 (2.9) |

| Cough | 17 (4.8) | 11 (6.4) |

| Nasal congestion | 12 (3.4) | 5 (2.9) |

| Rhinorrhoea | 12 (3.4) | 3 (1.7) |

| Postoperative pain | 19 (5.3) | 15 (8.7) |

| Ear pain | 14 (3.9) | 6 (3.5) |

Abbreviation: TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event (classified per the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 16.1).

Values are presented as n (%). If a patient experienced >1 episode of an adverse event in a system organ class, the patient was counted once for that preferred term.

Overall, there were no drug-related effects on otoscopic examinations, audiometric analyses, or tympanometry. Ninety-two percent of patients had both tubes patent at each time point, with no notable difference between treatment groups (see Table S1 online).

Air conduction for the majority of ears improved from baseline in both groups. By day 15, 80% of ears tested in the OTO-201 group had normal hearing, compared with 73% of TT alone ears (day 15 and day 29 shifts are found in Figure S2 online). The most frequent type of shift in PTA category at any visit was from mild to normal for the OTO-201 group and mild or slight to normal in the TT-alone group. PTA shifts of moderate severity from screening to days 15 and 29 were observed in individual ears and were therefore infrequent; most ears that had higher PTA values were found to have effusions.

At screening, the majority of ears in the OTO-201 and TT-alone groups had a tympanometry category of B with normal canal volume (see Figure S3a online). At days 15 and 29, most ears in each treatment group had a tympanometry category of B with a large canal volume, consistent with the presence of the TT and normal middle ear function (see Figure S3b and S3c online).

In both trials, most ears evaluated in the OTO-201 and TT-alone groups had a normal bone conduction category in the left, right, and nonspecific ear at screening and days 15 and 29. Proportions of ears with air-bone gap improvement in either ear or nonspecific ear (shifts in air-bone gap from >10 dB at screening to ≤10 dB at day 29) were larger in the OTO-201 group than the TT-alone group at most frequencies.

Discussion

The integrated analysis of 2 independent, identically designed phase 3 clinical trials in pediatric patients with bilateral MEE who underwent TTP supported the observations for each independent trial,9,10 specifically, a statistically significant treatment effect favoring OTO-201 over TT alone. A lower cumulative proportion of treatment failures at day 4 and at all visits through day 29 was noted in the patients who received OTO-201 versus those who received TT alone. Specifically, patients receiving TT alone were approximately twice as likely at day 15 (primary end point) to become a study treatment failure relative to those receiving TT plus OTO-201.

One of the components of treatment failure was the otorrhea-only treatment failures, which were documented by the blinded assessor (secondary end point). The cumulative proportion of treatment failure due to otorrhea was lower with OTO-201 treatment at day 4 and continuing through day 29, with approximately a two-thirds percentage reduction in otorrhea treatment failure risk for patients who received OTO-201 (7%) relative to TT alone (19%) at day 15 (absolute risk reduction of 12%). This reduction in the rate of otorrhea is consistent with what has been reported for otic drops in pediatric patients undergoing TT surgery.5-7 Furthermore, the observed otorrhea rate in the TT-alone group is similar to the range of 13% to 26% reported from a large meta-analysis and a literature review of the early postoperative period.4,7 Future research into the comparison of caregiver burden and cost-effectiveness of otic treatments should be considered. Interestingly, a large number of children with baseline serous effusions had treatment failures (OTO-201 vs TT alone, 21% vs 43%; Figure 5 ), which supports the finding that bacterial pathogens reside in serous effusions and are underdetected by traditional bacterial culture methods; otherwise, one would not have expected a different response between OTO-201 and TT alone.

There were no drug-related serious adverse events, and the majority of the adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. The most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events for the OTO-201 and TT-alone groups were expected for this type of administration and for this procedure in a pediatric population. OTO-201 administration had no evidence of increased tube occlusion and no negative effect on audiometry, tympanometry, or otoscopy when compared with TT alone.

Some limitations to this research exist. Patients undergoing concurrent operations were excluded from these trials. Future trials with OTO-201 that could be relevant in this patient setting might (1) have broader inclusion criteria, (2) research caregiver/patient centricity measures in line with or beyond current initiatives14 and validated tools,15 or (3) analyze large claims databases (to give insights into populations at highest risk for postoperative otorrhea, disparities in health care quality, and impact of patient access to health care).

Conclusion

The integrated analysis of 2 phase 3 trials demonstrated that a single intraoperative administration of a liquid suspension of ciprofloxacin microparticles in a thermosensitive polymer (OTO-201) that transitions to a gel showed a lower cumulative proportion of treatment failures through day 15 as compared with TT alone, when administered intratympanically for bilateral MEE at the time of TTP.

Author Contributions

Albert H. Park, investigator in the 2 phase 3 trials, drafted the manuscript; David R. White, investigator in the 2 phase 3 trials, drafted and revised the manuscript; Jonathan R. Moss, investigator in the 2 phase 3 trials and provided technical guidance in the trials, drafted and revised the manuscript; Moraye Bear, statistical analyses of the 2 phase 3 trials, drafted and revised the manuscript; Carl LeBel, involved in the trial design and operation for the 2 phase 3 trials, drafted the manuscript

Disclosures

Competing interests: Albert H. Park, Otonomy Inc—financial support for data presentation at the International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media and AAO-HNSF Annual Meeting and shareholder, Transit Scientific, LLC—consultant, Carbylan Therapeutics—shareholder; National Institutes of Health—coinvestigator, Thrasher site—principal investigator; David R. White, Otonomy Inc—financial support for advisory board participation, Alcon—grant; Jonathan R. Moss, Otonomy Inc—financial support for advisory board participation; Moraye Bear, Otonomy Inc—statistical consultant; Carl LeBel, Otonomy Inc—employee and shareholder.

Sponsorships: Otonomy Inc sponsored the trials.

Funding source: The trials and analyses were financially supported by Otonomy Inc.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their caregivers for their participation in these phase 3 trials, the clinical trial site staff members, trial coordinators, nursing and supporting staff, the Rho Inc project managers, trial monitors, statisticians, and remaining members of the trial teams.

We express our sincere gratitude to the following principal investigators who participated in the trials: T. Andrews, Pediatric Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Odessa and Tampa, Florida; J. Ansley, Carolina ENT, Orangeburg, South Carolina; M. Armstrong, Richmond ENT, Richmond, Virginia; K. Braat, ENT and Allergy Associates, Southampton and Riverhead, New York; R. Bridge, Precision Trials, Phoenix, Arizona; M. Brown, Iowa Head and Neck, Des Moines, Iowa; J. Byers, Greensboro ENT, Greensboro, North Carolina; F. Camilon, Orange, California; K. Chan, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado; D. Costa, St Louis University, Saint Louis, Missouri; D. Darrow, Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters, Norfolk, Virginia; F. Douglis, Conroe, Spring and Cleveland, Texas; A. Edmunds, Omaha ENT Clinic, Omaha, Nebraska; D. Ehmer, ENT Associates of Texas, McKinney, Frisco and Plano, Texas; E. Eksteen, MacKenzie HSc Centre, University Alberta, Edmonton, Canada; S. Engel, Coastal ENT, Neptune, New Jersey; D. Evans, Sacramento ENT Surgical and Medical Group, Sacramento, California; M. Friedman, Chicago ENT, Chicago, Illinois; A. Glaser, ENT and Allergy Associates, Hoboken and Rutherford, New Jersey; S. Goudy, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; R. Hekkenberg, ENT Health Corp, Barrie, Canada; D. Karas, Connecticut Pediatric Otolaryngology, North Haven and Madison, Connecticut; J. Koempel, Children’s Hospital LA, Los Angeles, California; F. Kozak, Pediatric ENT Clinic BC Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, Canada; B. Lanier, Central California Clinical Research, Fresno, California; B. Lansford, NEA Baptist Clinic, Jonesboro, Arkansas; K. Lee, Children’s at Legacy Pediatric Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Plano, Texas; D. Leitao, Pediatric Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; E. Mair, Charlotte Eye, ENT Associates, Charlotte, North Carolina; S. Manthei, Westfield Nevada Eye and Ear, Henderson, Nevada; T. Martin, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; K. Maxwell, Piedmont ENT Associates, Winston-Salem, North Carolina; J. McClay, Frisco ENT for Children, Dallas, Texas; M. Mehle, Clinical Research Solutions, Middleburg Heights, Ohio; T. Melson, Shoals Medical Trials, Inc, Sheffield, Alabama; S. Miller, Intermountain ENT Specialists, Salt Lake City, Utah; J. Moss, Charlotte Eye, ENT Associates, Matthews, North Carolina; A. Park, University of Utah Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, Utah; M. Parker, PMG Research of Wilmington, Wilmington, North Carolina; S. Patel, ENT for Children Clinical Office, Dallas and North Richland Hills, Texas; M. Poole, Georgia Ear Associates, Savannah, Georgia; G. Richter, University of Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, Arizona; J. Romett, Colorado ENT & Allergy, Colorado Springs, Colorado; J. Rosenbloom, Alamo ENT, LLC, San Antonio, Texas; S. Schoem, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut; D. Sommer, McMaster University Medical Centre, Hamilton, Canada; P. Spafford, Wall Street ENT Clinic, Saskatoon, Canada; Z. Spektor, Center for Pediatric ENT, Boynton Beach, Florida; C. Syms, Ear Medical Group, San Antonio, Texas; D. Welsh, Advanced ENT and Allergy, Louisville, Kentucky; D. White, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina; R. Younis, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, Florida; J. Zeiders, South Florida Pediatric Otolaryngology, Ft Lauderdale, Florida.

We thank Donna Simcoe of Simcoe Consultants Inc, funded by Otonomy Inc, for development of an early draft of the manuscript based on conversations with the authors.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

This article was presented at the 2015 AAO-HNSF Annual Meeting & OTO EXPO; September 27-30, 2015; Dallas, Texas. Drs Mair, Moss, and LeBel presented it on behalf of the OTO-201 Phase 3 Study Groups at the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology; April 22-26, 2015; Boston, Massachusetts. Drs Park and LeBel presented it on behalf of the OTO-201 Phase 3 Study Groups at the International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media; June 8, 2015; National Harbor, Maryland.

Supplemental Material: Additional supporting information may be found at http://otojournal.org/supplemental.

References

- 1. Mui S, Rasgon BM, Hilsinger RL, Jr, Lewis B, Lactao G. Tympanostomy tubes for otitis media: quality-of-life improvement for children and parents. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005;84:418-420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, et al. Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Owings MF, Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and inpatient procedures in the United States, 1996. Vital Health Stat. 1998;139:1-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hellström S, Groth A, Jörgensen F, et al. Ventilation tube treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:383-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ah-Tye C, Paradise JL, Colborn DK. Otorrhea in young children after tympanostomy-tube placement for persistent middle-ear effusion: prevalence, incidence, and duration. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1251-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kay DJ, Nelson M, Rosenfeld RM. Meta-analysis of tympanostomy tube sequelae. Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg. 2001;124:374-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Syed MI, Suller S, Browning GG, Akeroyd MA. Interventions for the prevention of postoperative ear discharge after insertion of ventilation tubes (grommets) in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD008512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boyd NH, Gottachall JA. Assessing the efficacy of tragal pumping: a randomized controlled trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:891-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mair EA, Park AH, Don D, Koempel J, Bear M, LeBel C. Safety and efficacy of intratympanic ciprofloxacin otic suspension in children with middle ear effusion undergoing tympanostomy tube placement: two randomized clinical trials [published online March 17, 2016]. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park A, LeBel C; on behalf of the OTO-201 Phase 3 Study Groups. Efficacy demonstrated in two phase 3 clinical trials of intratympanic extended-release ciprofloxacin gel in children with middle ear effusion undergoing tympanostomy tube placement. Paper presented at: International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media; June 8, 2015; National Harbor, MD Abstract OM2015166. http://www.otitismediasociety.org/ISOM_program_8%205x5%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang X, Fernandez R, Tsivkovskaia N, et al. OTO-201: nonclinical assessment of a sustained-release ciprofloxacin hydrogel for the treatment of otitis media. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35:459-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mair EA, Moss J, Dohar J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a sustained-exposure ciprofloxacin for intratympanic injection during tympanostomy tube surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;125:105-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CIPRODEX (ciprofloxacin 0.3% / dexamethasone 0.1%) sterile otic suspension [package insert]. Schaumburg, IL: Alcon Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. http://www.pcori.org/. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- 15. Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, Balzano A. Quality of life for children with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:1049-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.