Abstract

The Hippo pathway, which was identified from genetic screens in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, has a major size-control function in animals. All key components of the Hippo pathway, including the transcriptional coactivator Yorkie that is the most critical substrate and downstream effector of the Hippo kinase cassette, are found in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. As revealed by microarray and quantitative real-time PCR, expression of Hippo pathway genes is particularly enriched in several mitotic tissues, including the ovary, testis, and wing disc. Developmental profiles of Hippo pathway genes are generally similar (with the exception of Yorkie) within each organ, but vary greatly in different tissues showing nearly opposing expression patterns in the wing disc and the posterior silk gland (PSG) on day 2 of the prepupal stage. Importantly, the reduction of Yorkie expression by RNAi downregulated Yorkie target genes in the ovary, decreased egg number, and delayed larval-pupal-adult metamorphosis. In contrast, baculovirus-mediated YorkieCA overexpression upregulated Yorkie target genes in the PSG, increased PSG size, and accelerated larval-pupal metamorphosis. Together the results show that Yorkie potentially facilitates organ growth and metamorphosis, and suggest that the evolutionarily conserved Hippo pathway is critical for size control, particularly for PSG growth, in the silkworm.

Keywords: Hippo pathway, Yorkie function, size-control, ovary, silk gland, wing disc, domestication, Bombyx mori

Introduction

One fundamental biology question is how animals grow to the right size. The mechanism by which animals orchestrate the growth of their individual cells, tissues and organs is a long-standing mystery. Hormones and nutrients play certain roles in the regulation of tissue growth, but organ size is modulated in intact animals by genetic signaling networks. During the last decade, the Hippo pathway, which was first shown to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis during development and regeneration, has been recognized as one of the most important mechanisms of size control in animals. Many of the key components in the Hippo pathway and its basic signal transduction steps were originally discovered from genetic screens in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, and this pathway was later found to be the major size control mechanism that is evolutionarily and functionally conserved in vertebrates 1-6.

In Drosophila, key components of the Hippo pathway fall into three main classes: the Hippo kinase cassette, downstream transcriptional regulators, and upstream inputs (Fig. S1).

(i) The Hippo kinase cassette. Hippo, Salvador (Sav), Warts, and Mob-as-tumor-suppressor (Mats), which form the core of the Hippo pathway, were discovered in tumor suppressor genetic screens in Drosophila 7-17. Both Hippo and Warts are Ser/Thr kinases, and Sav and Mats are the adaptor proteins of Hippo and Warts, respectively. Importantly, Hippo-Sav phosphorylates and activates Warts-Mats, and the four proteins form a complex kinase cascade.

(ii) The Hippo downstream transcriptional regulators. The transcriptional coactivator Yorkie is the most critical substrate and downstream effector of the Hippo pathway 2, 18-24. Via direct protein-protein interaction, Yorkie is phosphorylated at three Ser residues (Ser168 is the most critical one in Drosophila) by Warts and is thus inactivated. Upon phosphorylation, Yorkie is relocated to the cytoplasm. When the Hippo pathway is inactivated, Yorkie functions as an oncogene in the nucleus by acting as a transcriptional coactivator. The Hippo pathway negatively regulates Yorkie activity by preventing its accumulation within the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, Yorkie binds and activates several transcription factors, including Scalloped (Sd), Homothorax (Hth), Teashirt, and Mothers against DPP, to induce gene expression. For example, Yorkie-Sd induces expression of cyclin E (cycE) and inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (diap1) to promote cell proliferation and to inhibit apoptosis, respectively 20, 21. In addition, the microRNA bantam, the oncogene Myc, and several Hippo upstream regulators are potent target molecules of Yorkie.

(iii) The Hippo upstream inputs. Many of the Hippo upstream regulators control cellular processes such as apical-basal cell polarity, planar cell polarity, and cell-cell adhesion 1, 2, 5. Fat is a large transmembrane protein that is critical for maintaining both planar cell polarity and the Hippo pathway. Dachsous (Ds) is a ligand for Fat 25-27. Crumbs (Crb) is an apical transmembrane protein that organizes both apical-basal polarity and the Hippo signaling 28-30. Expanded (Ex), Merlin (Mer), and Kibra colocalize at the apical domains of polarized epithelial cells, forming the Ex-Mer-Kibra complex. The three proteins physically interact with each other, and are partially redundant in activating the Hippo kinase cassette 31-34. Crb binds to Ex, affecting Ex stability and localization and thus the Hippo pathway, but Ds-Fat signaling is genetically distinguishable from Hippo regulation by the Ex-Mer-Kibra complex 2. Two other polarity complexes, the Scribble (Scrib) complex (Scrib; Discs large, Dlg; Lethal giant larva, Lgl) and the Par complex (Par3; Par6; atypical Protein kinase C, aPKC), are also involved in the Hippo pathway. The Lgl complex regulates apical-basal polarity by modulating the components of the Crb complex and the aPKC complex. In general, the Lgl complex activates the Hippo pathway, while the aPKC complex antagonizes the Lgl complex 35-37.

In mammals, a conserved Hippo kinase cascade and Yorkie function exist. However, the Hippo upstream inputs have additional complexity and, in some cases, are divergent from Drosophila. Mechanotransduction and G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling were identified as additional Hippo upstream regulators. Importantly, actin cytoskeleton and cellular tension appear to be the master mediators that integrate and transmit upstream signals to the Hippo kinase cascade and Yorkie function 3-6. The Hippo pathway is largely conserved in Caenorhabditis elegans 38. Moreover, key components in the Hippo pathway are found in the cnidarians, a very basal group of metazoans, and even in the unicellular ancestors of animals, the amoeboid holozoans, showing that the hippo pathway evolved well before the origin of Metazoa 39, 40. Moreover, a distinct interaction interface between Yorkie and Sd became structurally fixed in the eumetazoan common ancestor 41, showing that the ancient evolutionary history of the Hippo pathway as a key developmental mechanism in all animals.

Apart from Drosophila, the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori, is another model insect for general biology 42. In this study, we found that the Hippo pathway is evolutionarily conserved in the silkworm. Temporal and spatial expression patterns suggest that all of the Hippo pathway genes coordinately regulate organ growth and growth of the whole body. Moreover, Yorkie facilitates organ growth and accelerates metamorphosis. This study provides potential for promoting growth of the silk gland and thus silk yield by genetic modification of Yorkie in the silk gland, and suggests that the evolutionarily conserved Hippo pathway might play a crucial role in size control in the silkworm.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Bombyx larvae (P50 strain) were raised and provided by the Sericultural Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The silkworms were reared with fresh mulberry leaves in the laboratory using previously described conditions 43.

Gene identification

Gene identification was performed according to a method we reported previously 43. We mainly used SilkDB, http://silkworm.genomics.org.cn/, to search for potential Hippo pathway genes. First, we used the sequences of 18 key proteins in the Drosophila Hippo pathway to search against the GLEAN gene collection to identify Hippo pathway genes in the silkworm by local BLASTP, with an E-value threshold of 10-6. KAIKObase, http://sgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/KAIKObase/, was used for obtaining some full length cDNA sequences. The identified putative Hippo pathway genes were validated by searching the NCBI protein database with the putative Hippo pathway gene sequences as queries. Furthermore, each potential Hippo pathway gene was analyzed using Pfam to identify its domains. Finally, the identified silkworm Hippo pathway genes were used to search both SilkDB and KAIKObase to avoid missing any genes.

Phylogenetic analysis

At least one representative genome was selected for most orders of sequenced arthropod species, whose genomic information is available from NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov or predicted form the genome databases. The arthprod species (and Yorkie sequences) used are Ixodes scapularis (XP_002399565.1), Stegodyphus mimosarum (KFM74842.1), Strigamia maritima (SMAR013599-PA,predicted), Daphnia pulex (EFX70433.1), Timema cristinae (Tcri27797,predicted), Zootermopsis nevadensis (KDR09902.1), Drosophila melanogaster (XP_001976544.1), Tribolium castaneum (XP_970492.1), Apis mellifera (XP_391844.3), Pediculus humanus humanus (XP_002433100.1), Acyrthosiphon pisum (XP_001948042.1), Plutella xylostella (XP_011558709.1), Amyelois transitella (XP_013194179.1), Papilio polytes (XP_013134895.1), Helicoverpa armigera (ALO18798.1), and Bombyx mori (NP_001116819.1). The protein sequence of Drosophila Yorkie was used as the seed to search for putative orthologs across the whole genome by reciprocal BLAST. Multiple alignments of Yorkie proteins were then performed using MUSCLE 44, and the two WW domains of these alignments were extracted using Gblocks 45. Maximum-likelihood phylogenies were calculated using PhyML 46 with the JTT model for 100 replicates.

Microarray analysis

We initially used the genome-wide microarray data of the silkworm, which was previously performed in 2007 47, to profile the expression patterns of Hippo pathway genes in multiple larval tissues and during metamorphosis. From the public SilkDB, we downloaded the normalized microarray data for genome-wide gene expression in a number of tissues on day 3 of the fifth larval instar (L5-3) and at 19 sequential time points during metamorphosis. The expression pattern of the Hippo pathway genes was estimated from intensity values. If the normalized intensity of a Hippo pathway gene value exceeded 0, the gene was considered to be expressed 47.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis as previously described in detail 43. qPCR was carried out in a 20 μl reaction solution, which contains 10 μl of SYBR Green real-time PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad, USA), 5 μl of first strand cDNA template, and 0.5 mM of each primer. The iQ5 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA) was employed. Rp49 was chosen as a reference gene for qPCR analysis. Table S1 shows the primers used in this paper.

RNA interference of Yorkie in Bombyx larvae

EGFP (full length) and Yorkie (101-500 bp) dsRNA was generated using the T7 RiboMAX™ Express RNAi system (Promega, USA). At the initiation of the early wandering stage (IW), each larva was injected with either EGFP dsRNA (30 μg) or Yorkie dsRNA (30 μg). Twenty-four h after RNA interference (RNAi) treatment, the larvae were sacrificed 43. Ovary/testis, posterior silk gland (PSG), wing disc, and fat body tissues were collected for further analysis. For the RNAi experiments, 30 animals were used for each group, and 3 biological replicates were conducted.

Baculovirus-mediated overexpression of Yorkie and YorkieCA in Bombyx larvae

The Bombyx Yorkie Ser97 corresponds to the Drosophila Yorkie Ser168. According to the original discovery in Drosophila 19, Ser97 of the Bombyx Yorkie was mutated to Ala97 to generate the constitutive-active form of Yorkie (YorkieCA) by using PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis. The V5 tag (encoding the amino acid sequence of GKPIPNPLLGLDST) sequence was fused in the 5' end of Yorkie or YorkieCA to generate V5-Yorkie or V5-YorkieCA. V5-Yorkie or V5-YorkieCA was cloned into the EcoRI-NotI sites of the pFastBac-HTa (Invitrogen) plasmid, and DsRed2 (a type of red fluorescent protein, RFP) was used as a control.

We have previously employed the AcNPV ecdysteroid UDP-glucosyl transferase (egt) mutant for gene overexpression in Bombyx 48, 49, but this baculovirus does not produce sufficient Yorkie and YorkieCA proteins for functional studies. Here, using the homologous recombination technique, we generated an egt mutant of Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrosis baculovirus (BmNPV). This virus allows silkworms to survive until pupation and to produce sufficient Yorkie and YorkieCA proteins. The pFastBac-HTa plasmids of V5-Yorkie and V5-YorkieCA were then transformed into DH10BacΔEGT bacteria 47 to prepare bacmid DNA according to the protocol of the Bac-to-Bac system. Bm-N cells were transfected with bacmid DNA (1 μg/ml) using Cellfectin II transfection reagent (Invitrogen). After 7 days, P1 virus was collected. The P1 virus was then used to prepare P2 virus after another 3 days. Bm-N cells infected with the P2 virus were collected for silkworm injection experiments on L5-2. One hundred and twenty h after virus treatment, the larvae were sacrificed for analyses. For the overexpression experiments, 30 animals were used for each group, and 3 biological replicates were conducted.

Western blotting and immunohistochemistry

The V5 antibody (1:1000) (Invitrogen, USA) was used to detect the overexpressed V5-Yorkie or V5-YorkieCA in the PSG by Western blotting as previously described in detail 49.

For detecting the overexpressed V5-Yorkie or V5-YorkieCA by immunohistochemistry, the newly dissected fat body tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 min at room temperature. Fat body tissues were blocked in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% BSA and 1% Triton-X (PBSBT) for 1 h, and then incubated with the V5 antibody (diluted 1:50) at 4°C overnight. Fat body tissues were washed multiple times for 1 h in PBSBT, and then incubated with a FITC-(green) conjugated secondary antibody (diluted 1:200) for 2 h. DAPI (Sigma) was added to label nuclei. Fat body tissues stained with V5 antibody and DAPI were imaged using an FV10-ASW confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan) at 20×magnification 49.

Statistics

Throughout the study, the experimental data were analyzed using Student's t-test: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. Meanwhile, the values are represented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Identification of key genes in the Hippo pathway

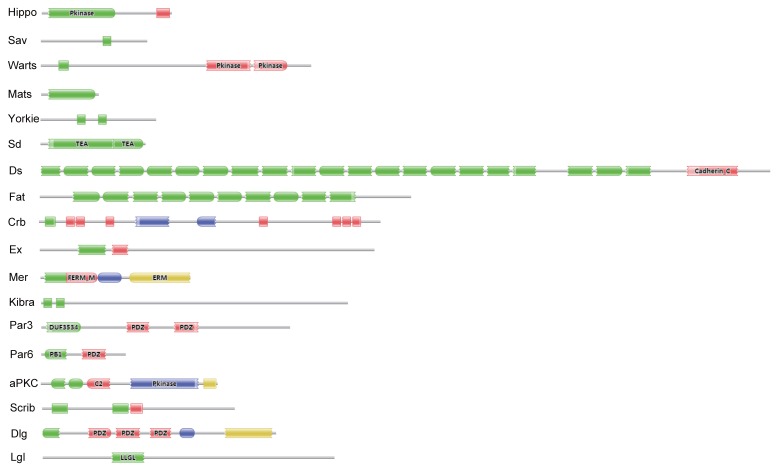

Eighteen key proteins in the Drosophila Hippo pathway were used in BLASTP queries against the SilkDB and KAIKObase databases. Each potential protein in the Bombyx Hippo pathway was validated by searching its known orthologs from the NCBI protein database and further searching its conserved domain(s) with the Pfam program. As a result, a total of 18 putative genes in the Hippo pathway were identified in the silkworm genome. Their encoding proteins fall into three main classes: the Hippo kinase cassette (Hippo, Sav, Warts, and Mats), downstream transcriptional regulators (Yorkie and Sd), and upstream inputs (Ds and Fat; Crb; Ex, Mer, and Kibra; Scrib, Dlg, and Lgl; and Par3, Par6, and aPKC) (Fig. S1). As revealed by domain analysis (Fig. 1), Hippo is a Ste20 family protein kinase, Sav contains one WW domain, Warts is an NDR family protein kinase, and Mats has a Mob1/phocein domain. Yorkie contains two WW domains, and Sd belongs to the TEA transcriptional enhancer factor superfamily. The transmembrane proteins Ds and Fat contain 22 and at least 10 (the Fat sequence is likely incomplete) cadherin repeats, respectively. The transmembrane protein Crb has multiple epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains and Laminin G-like domains. Ex and Mer are similar to each other, containing FERM (4.1 protein, ezrin, radixin, moesin) domains; Kibra has two WW domains, one C2 domain, and one component of oligomeric Golgi complex 7 (COG7) domain. Scrib has multiple leucine-rich repeats; Dlg contains one Guanylate kinase domain and three PDZ domains, and Lgl belongs to the WD40 superfamily. Par3 contains two PDZ domains and one DUF3534 domain; Par6 has one PDZ domain and one PB1 domain, while aPKC is an atypical protein kinase C.

Fig 1.

Significant domains of 18 Hippo pathway genes in Bombyx. The program Pfam was used for domain identification. Please see the details of domain analysis in the text. * The Fat sequence is likely incomplete in the Bombyx genome.

In SilkDB, eight Hippo pathway genes have evidence for mRNA expression with expressed sequence tags (ESTs), which were collected from 36 different cDNA libraries. Based on the EST information, Sd shows the highest transcript level with 10 hits. The largest Hippo pathway protein (2764 amino acids) and the smallest one (217 amino acids) are encoded by Ds and Mats, respectively. Of the 18 Hippo pathway genes, 17 are dispersed on 11 chromosomes and 1 (Mer) on an unmapped scaffold. With the exception of Fat, the other 17 Hippo pathway genes have accession numbers in NCBI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the 18 Hippo pathway genes in the Bombyx genome.

| NO. | gene | SilkDB ID | Chr. | Scaffold | Position | EST | Probe | Size (AA) | NCBI ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hippo | BGIBMGA013478 | 5 | nscaf3075 | (+)1302878..1290675 | 0 | sw08605 | 492 | NP_001116818.1 |

| 2 | Sav | BGIBMGA004937 | 25 | nscaf2822 | (-)912627..918022 | 0 | sw11181 | 402 | XP_004924516.1 |

| 3 | Warts | BGIBMGA006330 | 6 | nscaf2852 | (+)1986876..1992247 | 1 | sw05368 | 1025 | XP_004923559.1 |

| 4 | Mats | BGIBMGA013463 | 6 | nscaf3074 | (+)146991..151388 | 0 | sw05526 | 217 | XP_004926597.1 |

| 5 | Yorkie | BGIBMGA003682 | 5 | nscaf2674 | (+)4049793..4052521 | 2 | sw03123 | 437 | NP_001116819.1 |

| 6 | Sd | BGIBMGA001129 | 13 | nscaf1898 | (+)4585777..4618439 | 10 | sw14392 | 397 | XP_004928021.1 |

| 7 | Ds | BGIBMGA010453 | 12 | nscaf2993 | (-)1494834..1480580 | 0 | sw11749 | 2764 | XP_004929431.1 |

| 8 | Fat | BGIBMGA010597 | 12 | nscaf2995 | (+)253973..259252 | 0 | sw21999 | 1407 | NO |

| 9 | Crb | BGIBMGA007609 | 15 | nscaf2888 | (-)9505337..9522337 | 0 | sw11252 | 1294 | XP_004928825.1 |

| 10 | Ex | BGIBMGA010558 | 12 | nscaf2993 | (+)6011036..6015638 | 5 | sw03959 | 1268 | XP_004929583.1 |

| 11 | Mer | BGIBMGA014502 | UN | nscaf749 | (-)6487..18440 | 0 | sw11071 | 567 | XP_004933720.1 |

| 12 | Kibra | BGIBMGA009269 | 14 | nscaf2943 | (+)1377742..1396051 | 2 | sw05915 | 1162 | XP_004922701.1 |

| 13 | Scrib | BGIBMGA005373 | 8 | nscaf2828 | (-)1127705..1141772 | 1 | sw18238 | 729 | XP_004932102.1 |

| 14 | Dlg | BGIBMGA010382 | 12 | nscaf2993 | (-)6758200..6776168 | 0 | sw19956 | 884 | XP_004929498.1 |

| 15 | Lgl | BGIBMGA005570 | 17 | nscaf2829 | (-)1712186..1720814 | 3 | sw12635 | 1105 | XP_004921966.1 |

| 16 | Par3 | BGIBMGA006557 | 10 | nscaf2855 | (+)6535850..6549347 | 0 | sw11025 | 942 | XP_004930528.1 |

| 17 | Par6 | BGIBMGA004440 | 20 | nscaf2795 | (+)718639..722191 | 1 | sw09724 | 319 | XP_004922525.1 |

| 18 | aPKC | BGIBMGA014132 | 8 | nscaf463 | (+)1220257..1230024 | 0 | sw05322 | 669 | NP_001036978.1 |

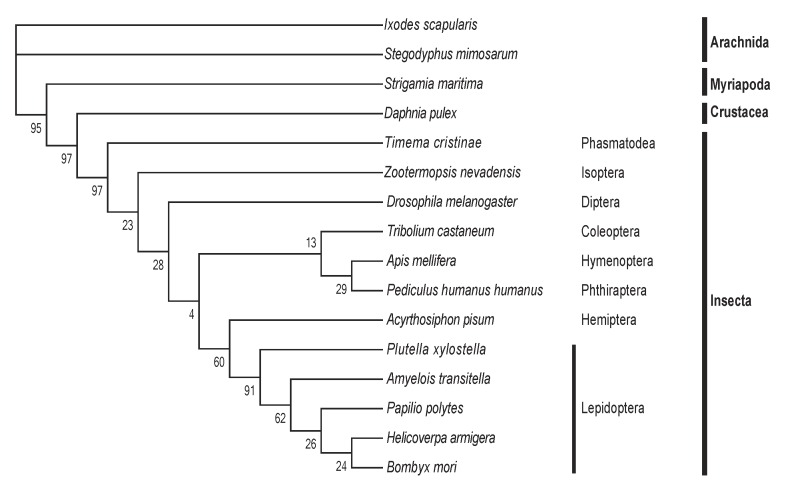

The 18 Hippo pathway genes were also searched from 16 arthropod genomes. Each arthropod contains at least one copy (with occasionally gene duplication) of each of the 18 genes, indicating that the Drosophila Hippo pathway is evolutionarily conserved in Arthropoda. We selected Yorkie, which is the most critical substrate and downstream effector of the Hippo pathway, to perform a multiple sequence alignment (Table S2). The comparison analysis reveals that the Yorkie proteins among five lepidopteran species share the highest identity (73-89%) and that the identity of any two arthropod Yorkie proteins is greater than 34%. A previous phylogenetic analysis shows that arthropod Yorkie proteins form a separate clade among all the animal Yorkie orthologs 39. We then constructed a phylogenetic tree on the basis of the two WW domains of Yorkie proteins from the 16 arthropods (Fig. 2), including the five lepidopteran insects for more informative comparison. Importantly, the nodes within the lepidopteran clade present a strong bootstrap support, and the phylogenetic tree shows a clear separation between Insecta and non-Insecta50.

Fig 2.

The phylogenetic tree of Yorkie in Arthropoda. At least one representative genome was selected for most orders of sequenced arthropod species. In total, 16 arthropods were used, including Arachnida (2 species), Myriapoda, Crustacea, and Insecta (12 species, including five lepidopteran species). The protein sequence of Drosophila Yorkie was used to search putative orthologs across the whole genomes of the 16 arthropods by reciprocal BLASTP. Multiple alignments of the two WW domains of Yorkie proteins were then performed using MUSCLE, and the conserved blocks of these alignments were extracted using Gblocks. The phylogeny was calculated using PhyML with the JTT model for 100 replicates.

Expression of the Hippo pathway genes is enriched in mitotic tissues

To understand the physiological function of the Hippo pathway in Bombyx, we initially surveyed the temporal and spatial expression patterns of all 18 Hippo pathway genes by microarray analysis. All of the 18 genes have corresponding probes on the oligonucleotide chip 47. We investigated the tissue distribution of the 18 genes on L5-3 using the microarray data of tissue-specific expression 47. The expression of 7 genes (including Yorkie) can be detected in at least one of the selected tissues, including testis, ovary, head, integument, Malpighian tubules, fat body, hemocytes, anterior and middle silk glands, and PSG (Fig. S2). Significantly, most genes were highly expressed in the gonad (ovary and testis) and the head compared to other tissues.

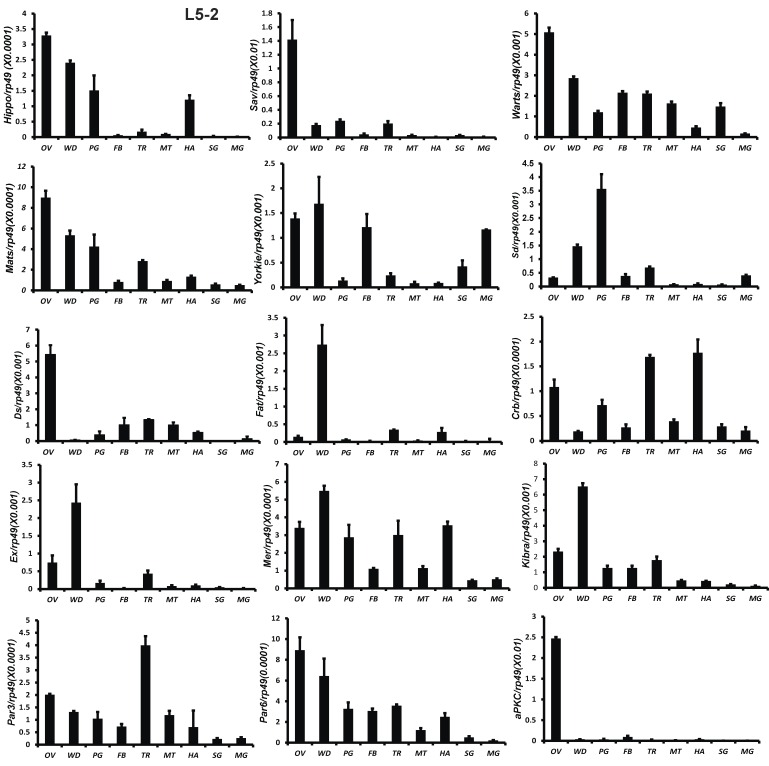

All 18 genes were also analyzed by qPCR using total RNA isolated from 9 tissues, including fat body, midgut, ovary, wing disc, trachea, Malpighian tubules, hemocyte, prothoracic gland, and silk gland on L5-2. Except Sd and Fat, the other 16 genes were abundantly expressed in the gonad. Fat and Ex were highly expressed in the wing disc. Sd expression was high in the prothoracic glands (Fig. 3). The tissue distribution patterns of Scrib, Dlg, and Lgl were previously reported by Qi et al 51. In consistent with the microarray data, qRCR analysis revealed that gene expression of the Hippo pathway components is particularly enriched in several mitotic tissues, including the gonad and wing disc on L5-2.

Fig 3.

Tissue distribution patterns of Hippo pathway genes on day 2 of the fifth larval instar. OV (ovaries); WD (Wing disc); PG (Prothoracic gland); FB (Fat body); TR (Trachea); MT (Malpighian tubule); HA (Hemocytes); SG (Silk gland); MG (Midgut). Rp49 is used as an internal control. Relative mRNA levels are indicated as the ratios of mRNA levels between the target gene and Rp49. Error bars represent the SDs of three independent replicates in this and all subsequent figures. In each replicate, ten animals were used, and triplicate qPCR analyses were conducted.

Developmental profiles of the Hippo pathway genes are generally similar within each organ but vary greatly in different tissues

We initially investigated the temporal expression patterns of 18 Hippo pathway genes from L5-4 to the adult stage by using the microarray data of developmental changes of mRNA 47. The expression of 11 of the 18 genes (including Yorkie) was detected (Fig. S3). With the exception of Par3 and Fat, which were only detected in male pupae, the expression of the other 9 genes gradually rises from the larval stage to the pupal stage to the adult stage.

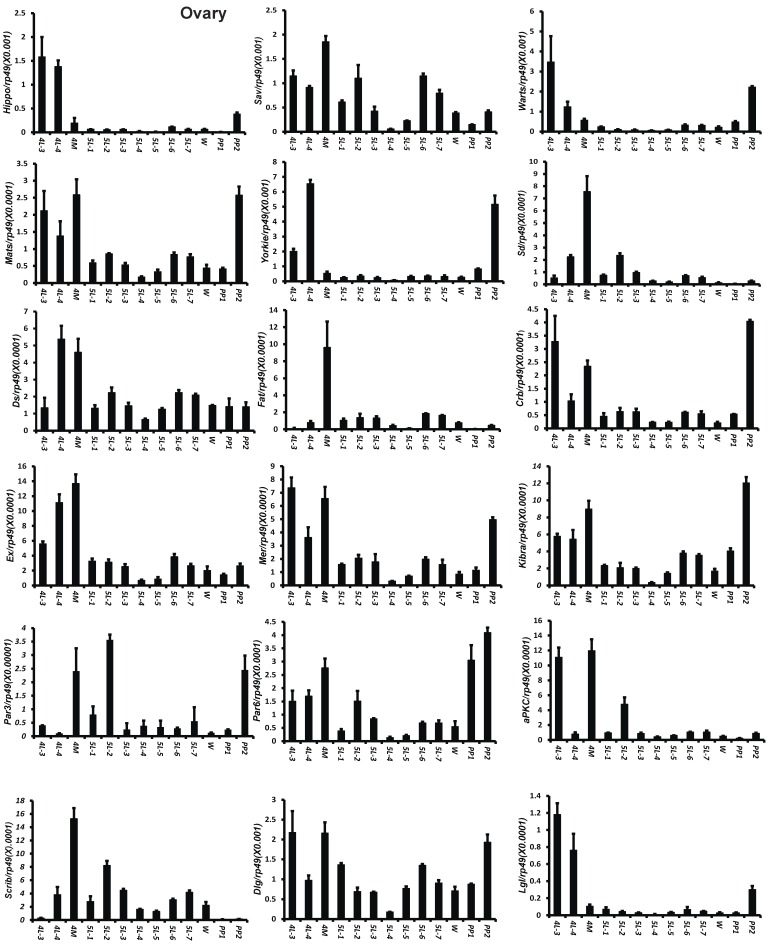

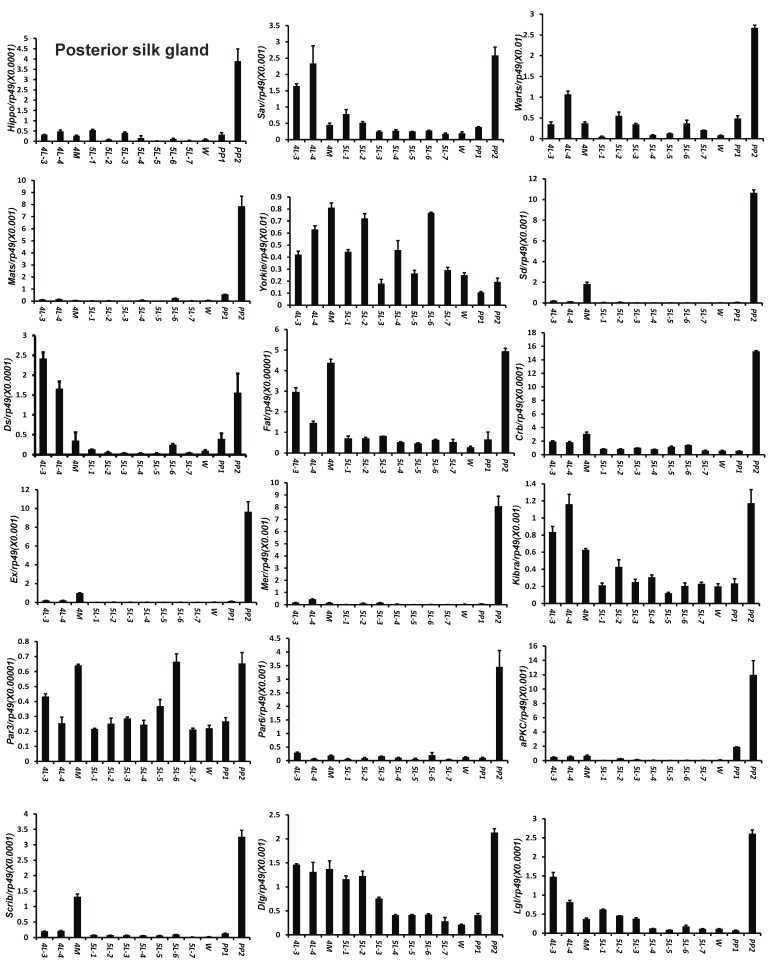

To understand the detailed developmental profiles of the 18 genes during Bombyx larval-pupal metamorphosis, we performed qPCR analysis using total RNA isolated from the ovary, wing disc, and PSG dissected from 4L-3 to day 2 of the prepupal stage (PP2). In the ovary, with the exception of Sd, Fat, Par3, and Scrib, the expression levels of the other 14 genes were higher in the fourth instar than in the fifth instar, and the expression levels of 11 of the 18 genes (Hippo, Warts, Mats, Yorkie, Crb, Mer, Kbira, Dlg, Lgl, Par3, and Par6) increased on PP2 (Fig. 4). In the wing disc, the expression levels of all 18 genes were low on 4L-3 and relatively high from 4L-4 to PP1; with the exception of Yorkie, the expression levels of the other 17 genes decreased on PP2 (Fig. S4). In the PSG, the expression levels of 9 of the 18 genes (Hippo, Mats, Sd, Crb, Ex, Mer, Scrib, Par6, and aPKC) were low from 4L-3 to PP1; the expression levels of 6 of the 18 genes (Sav, Ds, Fat, Kibra, Dlg, and Lgl) gradually decreased from 4L-3 to PP1, while the expression levels of Warts, Yorkie, and Par3 were quite stable during this period. Apart from Yorkie, the expression levels of the other 17 genes significantly increased on PP2 (Fig. 5). Collectively, the developmental profiles of the 18 Hippo pathway genes were quite similar (with the exception of Yorkie) within each organ but varied greatly in different tissues, and all 18 Hippo pathway genes show nearly opposing expression patterns in the wing disc and the PSG on PP2.

Fig 4.

Developmental expression profiles of 18 Hippo pathway genes in the ovary from day 3 of the fourth larval instar to day 2 of the prepupal stage. 4L-3 and 4L-4, day 3 and 4 of the fourth larval instar; 4M, the 4th molting; 5L-1 to 5L-7, day 1 to 7 of the fifth larval instar; W, the wandering stage; PP1 and PP2, day 1 and 2 of the prepupal stage.

Fig 5.

Developmental expression profiles of 18 Hippo pathway genes in the posterior silk gland from day 3 of the fourth larval instar to day 2 of the prepupal stage. 4L-3 and 4L-4, day 3 and 4 of the fourth larval instar; 4M, the 4th molting; 5L-1 to 5L-7, day 1 to 7 of the fifth larval instar; W, the wandering stage; PP1 and PP2, day 1 and 2 of the prepupal stage.

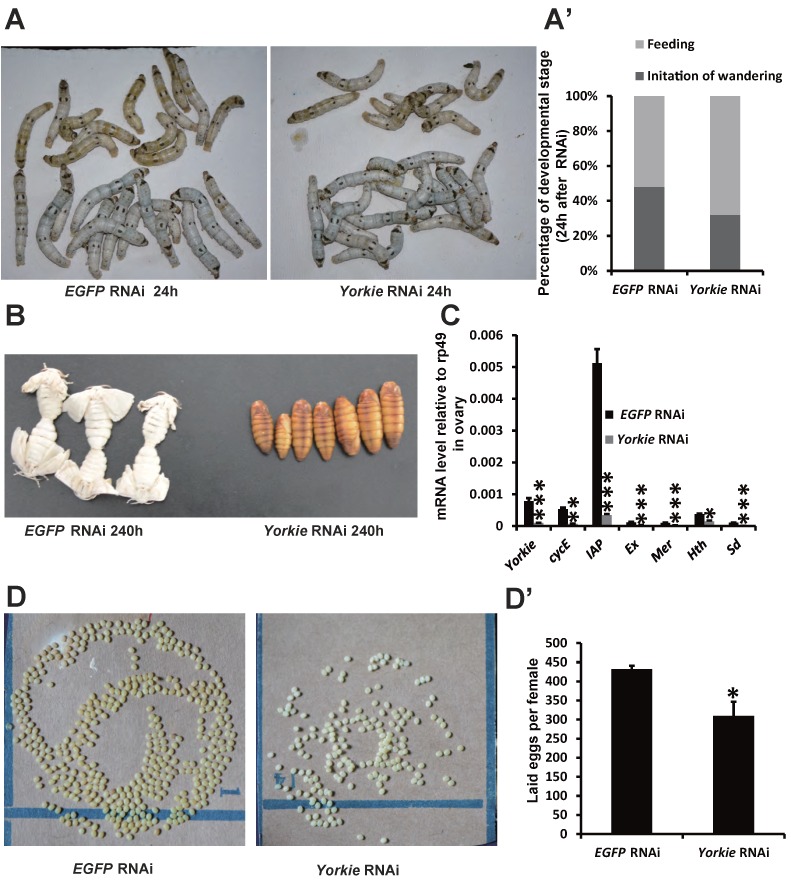

Yorkie RNAi delays metamorphosis and ovary maturation

In Drosophila, Yorkie mutants display reduced organ growth 18. Thus, we investigated whether Yorkie is important for Bombyx development using RNAi to suppress Yorkie expression (Yorkie RNAi) at IW. Interestingly, the wandering behavior was apparently delayed 12 h after Yorkie RNAi, compared with the EGFP RNAi control animals (Figs. 6A and 6A'). Moreover, all of the Yorkie RNAi animals remained at the pupal stages 240 h after RNAi treatment, while all of the control animals had already emerged as adults. The delay of adult emergence in the Yorkie RNAi animals was about 12 h (Fig. 6B). Notably, 24 h after Yorkie RNAi, Yorkie expression in the ovary decreased by approximately 90% compared with the control levels; moreover, six Yorkie target genes, including cycE, IAP, Ex, Mer, Hth, and Sd, were significantly downregulated by Yorkie RNAi (Fig. 6C). Importantly, the Yorkie RNAi females laid fewer eggs than the control females (Fig. 6D and D'). In addition, the efficiency of Yorkie RNAi in the wing disc was moderate, and Yorkie RNAi only slightly decreased its organ size (Figs. S5A and S5A'). The RNAi experiment indicates that Yorkie is required for timely metamorphosis and ovary maturation in Bombyx.

Fig 6.

Yorkie RNAi delays metamorphosis and ovary maturation. (A and A') Compared to the EGFP RNAi control silkworms, the Yorkie RNAi silkworms showed delayed larval-pupal metamorphosis at 24 h after dsRNA treatment. The chart (A') shows the quantification of silkworms in (A): at the feeding stage or at the initiation of the wandering stage. (B) Compared to the EGFP RNAi control silkworms, the Yorkie RNAi silkworms showed delayed emergence at 240 h after dsRNA treatment. (C) A comparison of the mRNA levels of the Yorkie target genes in the ovary 24 h after dsRNA treatment. (D and D') Compared to the EGFP RNAi control silkworms, the Yorkie RNAi silkworm moths showed reduced egg numbers. The chart (D') shows the quantification of silkworm egg numbers in (D).

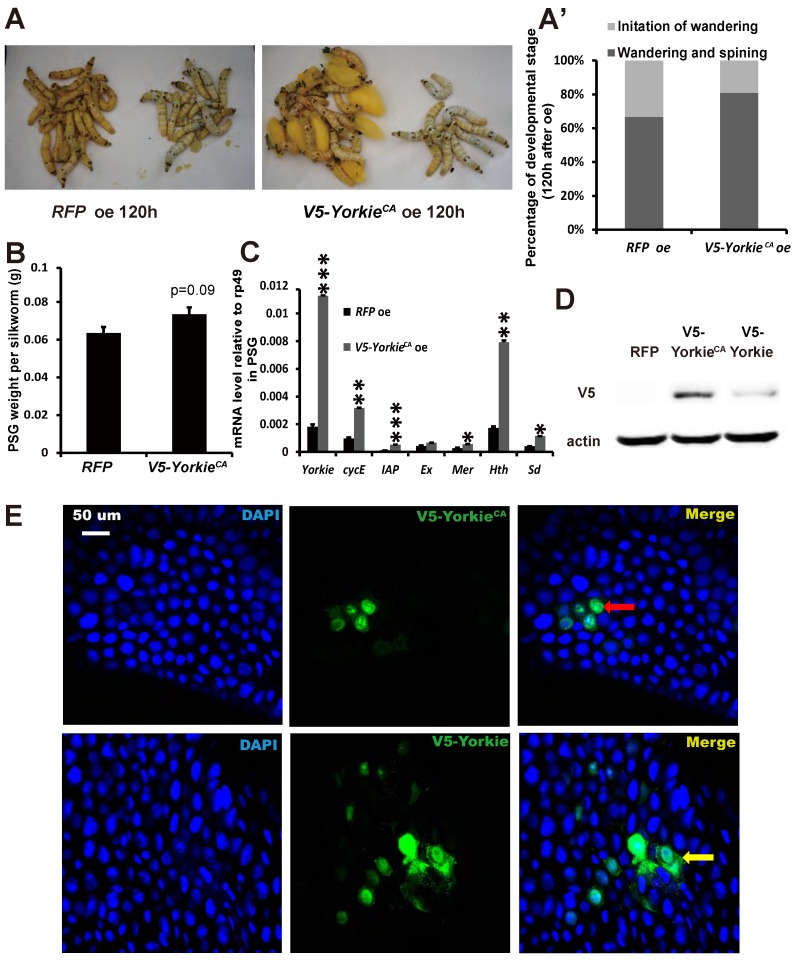

YorkieCA overexpression accelerates pupation and PSG organ size

In Drosophila, Yorkie overexpression induces organ overgrowth 18. To complement the Yorkie RNAi experiments, we conducted V5-YorkieCA overexpression on L5-2 and observed the effects on Bombyx metamorphic development. The wandering behavior was apparently accelerated 120 h after V5-YorkieCA overexpression, compared with the RFP overexpression control animals (Figs. 7A and 7A'). Interestingly, PSG size was increased approximately 20% by V5-YorkieCA overexpression (Fig. 7B). V5-YorkieCA expression in the ovary increased by 6-fold; meanwhile, six Yorkie target genes were upregulated 3-10-fold by Yorkie overexpression (Fig. 7C). In addition, the efficiency of V5-YorkieCA overexpression in the wing disc was moderate, and Yorkie overexpression only slightly increased its organ size (Figs. S5B and S5B'). The overexpression experiment shows that Yorkie facilitates metamorphosis and promotes PSG growth in Bombyx.

Fig 7.

YorkieCA overexpression accelerates pupation and PSG size. (A and A') Compared to the RFP overexpression (RFP oe) control silkworms, the YorkieCA overexpression (YorkieCA oe) silkworms showed accelerated larval-pupal metamorphosis at 120 h after baculovirus infection. The chart (A') shows the quantification of silkworms in (A): at the initiation of the wandering stage or at the wandering and spinning stages. (B) Compared to the RFP-overexpressed control silkworms, the YorkieCA-overexpression silkworms showed size increases of the posterior silk gland (PSG) at 120 h after baculovirus infection. (C) A comparison of mRNA levels of the Yorkie target genes in the posterior silk gland at 120 h after baculovirus infection. (D) Western blotting analysis of the protein levels of overexpressed V5-YorkieCA and V5-Yorkie in the posterior silk gland at 120 h after baculovirus infection. The V5 antibody detects the overexpressed V5-YorkieCA and V5-Yorkie at MW ~75 kDa. (E) Immmunohistochemistry analysis of the protein levels of overexpressed V5-YorkieCA and V5-Yorkie in the fat body at 120 h after baculovirus infection. As denoted by the yellow and red arrows, respectively, the overexpressed V5-YorkieCA always localized in the nuclei of the fat body cells, while the overexpressed V5-Yorkie localized in both nuclei and cytoplasm of the fat body cells.

In preliminary experiments, we found that compared to RFP overexpression, V5-Yorkie overexpression had very weak stimulatory effects on metamorphosis and PSG growth. As detected by Western blotting in the PSG using the V5 antibody, V5-YorkieCAoverexpression yielded approximately 5-fold higher protein level than V5-Yorkie overexpression (Fig. 7D). As monitored by immunohistochemistry using the V5 antibody, the overexpressed V5-YorkieCAmainly localized in the nuclei of the fat body cells, while the overexpressed V5-Yorkie localized in both nuclei and cytoplasm of the fat body cells (Fig. 7E). The more abundant protein level and the nuclear localization of the overexpressed V5-YorkieCA are likely responsible for its better stimulatory effects on metamorphosis and PSG growth compared to the overexpressed V5-Yorkie.

Discussion

As revealed by microarrays and qPCR, the tissue distribution and developmental profiles of the Hippo pathway genes suggest that the Hippo pathway regulates Bombyx organ growth in a context-specific manner. Expression of the Hippo pathway genes on L5-3 or L5-2 is particularly enriched in several mitotic tissues, including the gonad and wing disc (Figs. S2 and 3). It is likely that the growth of mitotic tissues is restricted by the Hippo pathway at this period. In consistent with this hypothesis, during the larval stages, the mitotic tissues do not grow as dramatically as other larval tissues, such as the silk gland and the fat body that undergo rapid endocycles. During the larval stages, expression levels of the Hippo pathway genes are generally higher at the fourth instar than those at the fifth instar (Figs. 4, 5, and Fig. S4), in agreement with a dramatic body growth at the fifth instar. Moreover, as revealed by microarray analysis, expression levels of the Hippo pathway genes gradually increase from the larval stage through the pupal stage to the adult stage (Fig. S3), agreeing that the obsolete larval tissues undergo massive programmed cell death and histolysis during metamorphosis 52. It is possible that the growth of larval tissues is tightly limited and their death is promoted by the Hippo pathway during the non-feeding pupal and adult stages. Interestingly, some Hippo pathway genes are expressed in males but not in females during the pupal stages, implying that pupal development is more restricted by the Hippo pathway in males than in females.

Pronouncedly, the developmental profiles of Hippo pathway genes are generally similar to each other (with the exception of Yorkie) within each tissue, but vary greatly in different tissues, including the ovary, wing disc, and PSG. It is likely that the Hippo pathway genes coordinate and control the growth of each organ, but how the pathway regulates this growth might be different in distinct organs. For example, the expression patterns of 18 Hippo pathway genes on PP2 are opposite between the wing disc and PSG (Fig. 5 and Fig. S4). On PP2, the wing disc undergoes dramatic growth 53, while the PSG stops cell proliferation and begins programmed cell death with decreased expression of cycE and IAP 54-57. Surprisingly, expression of all genes in the Hippo kinase cassette and upstream inputs is low in the wing disc on PP2, but expression of Yorkie remains high (Fig. S4), suggesting that Yorkie might promote its dramatic growth at this developmental stage. In contrast, expression of all genes in the Hippo kinase cassette and upstream inputs sharply increases in the PSG on PP2, but expression of Yorkie decreases (Fig. 5), implying that a low Yorkie activity might allow programmed cell death and histolysis to occur in the PSG at this developmental stage. Together, the nearly opposing expression patterns of the Hippo pathway genes between the wing disc and the PSG on PP2 raise the possibility that the Hippo pathway might differently regulate growth of distinct tissues at particular developmental stages.

To understand if physiological function of the Hippo pathway is conserved in Bombyx, we performed both loss- and gain-of-function studies of Yorkie. It is necessary to note that Yorkie RNAi at IW did not cause lethal phenotypes. One reason could be the high expression levels of genes in the Hippo kinase cassette and upstream inputs during the pupal stages (Fig. S3) and these genes might have been lowered Yorkie activity during metamorphosis. Meanwhile, although the efficiency of Yorkie RNAi was high in the ovary, it was moderate in the wing disc and fat body but extremely low in the PSG (Fig. 6, Figs. S5, S6). The strongest phenotypes caused by Yorkie RNAi or Yorkie overexpression are changes in metamorphosis. To our understanding, this is the first time to report that Yorkie facilitates metamorphosis in insects. In accordance with the 20E signaling that determines Bombyx metamorphosis 53, 58-60, Yorkie promotes timely metamorphosis (Figs. 6A-6B, 7A, and 7A'). Compared with the 20E signaling that causes programmed cell death 53, 60-62, Yorkie promotes growth of organs, including the ovary, wing disc, and PSG (Figs. 6D, 6D', 7B, and Fig. S5). Using the newly developed CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout method 63 and the GAL4/UAS system 56, one might understand how Yorkie regulates organ growth and metamorphosis at the embryonic and early larval stages in Bombyx.

During thousands of years of artificial selection, the body size of the domesticated silkworm has been improved; moreover, the organ size of the silk gland has been even more significantly improved. During the fifth larval instar, the silk gland grows dramatically and produces a great amount of fibroin. In terms of protein synthesis, the silk gland is one of the most efficient organs in animals 42. Using the GAL4/UAS system, we have previously demonstrated that Ras signaling, together with insulin-like peptides and nutrients, plays a critical role in the regulation of silk gland growth and silk yield 54, 56, 57. Considering that baculovirus-mediated YorkieCA overexpression accelerates PSG growth (Fig. 7), we assume that YorkieCA overexpression in the PSG should have similar stimulatory effects on PSG growth to Ras1CA overexpression. In order to improve silk yield more efficiently, we are considering simultaneous overexpression of YorkieCA and Ras1CA in the PSG. Combining the powerful tools of omics, genetics, and bioinformatics, we have sought to understand how the genetic signaling networks, including 20E signaling, Ras signaling and the Hippo pathway, coordinately regulate the size of the silk gland and the whole body during silkworm domestication.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables and figures.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (31302034 and 31330072), the National Program for the Development of New Transgenic Species of China (2014ZX08010-016B), and Shanghai Municipal Nature Science Fund (13ZR1433100). English was polished by the Nature Publishing Group.

Authors' contributions

S Li conceived and designed the experiments. S Liu, PZ, LZ, and HQ performed the research and analyzed the data. SZ constructed the phylogenetic tree and analyzed the arthropod genomes. S Li, S Liu, and LZ wrote the paper. HS, GZ, and ZW provided important reagents. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staley BK, Irvine KD. Hippo signaling in Drosophila: recent advances and insights. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:3–15. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tremblay AM, Camargo FD. Hippo signaling in mammalian stem cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:818–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enderle L, McNeill H. Hippo gains weight: added insights and complexity to pathway control. Sci Signal. 2013;6:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: Regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 2013;27:355–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao B, Guan KL. Hippo pathway key to ploidy checkpoint. Cell. 2014;158:695–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Justice RW, Zilian O, Woods DF, Noll M, Bryant PJ. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:534–46. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu T, Wang W, Zhang S, Stewart RA, Yu W. Identifying tumor suppressors in genetic mosaics: the Drosophila lats gene encodes a putative protein kinase. Development. 1995;121:1053–63. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Tao C, Verstreken P, Hiesinger PR, Bellen HJ. et al. Shar-pei mediates cell proliferation arrest during imaginal disc growth in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:5719–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tapon N, Harvey KF, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Schiripo TA, Haber D. et al. Salvador Promotes both cell cycle exit and apoptosis in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Cell. 2002;110:467–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell. 2003;114:457–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia J, Zhang W, Wang B, Trinko R, Jiang J. The Drosophila Ste20 family kinase dMST functions as a tumor suppressor by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2514–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1134003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantalacci S, Tapon N, Leopold P. The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell-cycle exit in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:921–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Udan RS, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Tao C, Halder G. Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:914–20. doi: 10.1038/ncb1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu S, Huang J, Dong J, Pan D. Hippo encodes a Ste-20 family protein kinase that restricts cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in conjunction with salvador and warts. Cell. 2003;114:445–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai ZC, Wei X, Shimizu T, Ramos E, Rohrbaugh M, Nikolaidis N. et al. Control of cell proliferation and apoptosis by mob as tumor suppressor, mats. Cell. 2005;120:675–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei X, Shimizu T, Lai ZC. Mob as tumor suppressor is activated by Hippo kinase for growth inhibition in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2007;26:1772–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell. 2005;122:421–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA. et al. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130:1120–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D. The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;14:388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, Jiang J. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev Cell. 2008;14:377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goulev Y, Fauny JD, Gonzalez-Marti B, Flagiello D, Silber J, Zider A. SCALLOPED interacts with YORKIE, the nuclear effector of the hippo tumor suppressor pathway in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh H, Irvine KD. In vivo regulation of Yorkie phosphorylation and localization. Development. 2008;135:1081–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.015255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh H, Irvine KD. In vivo analysis of Yorkie phosphorylation sites. Oncogene. 2009;28:1916–27. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett FC, Harvey KF. Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva E, Tsatskis Y, Gardano L, Tapon N, McNeill H. The tumor-suppressor gene fat controls tissue growth upstream of expanded in the hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2081–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho E, Feng Y, Rauskolb C, Maitra S, Fehon R, Irvine KD. Delineation of a Fat tumor suppressor pathway. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1142–50. doi: 10.1038/ng1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CL, Gajewski KM, Hamaratoglu F, Bossuyt W, Sansores-Garcia L, Tao C. et al. The apical-basal cell polarity determinant Crumbs regulates Hippo signaling in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15810–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ling C, Zheng Y, Yin F, Yu J, Huang J, Hong Y. et al. The apical transmembrane protein Crumbs functions as a tumor suppressor that regulates Hippo signaling by binding to Expanded. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10532–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004279107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson BS, Huang J, Hong Y, Moberg KH. Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein Expanded. Curr Biol. 2010;20:582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, Tao C. et al. The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:27–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumgartner R, Poernbacher I, Buser N, Hafen E, Stocker H. The WW domain protein Kibra acts upstream of Hippo in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2010;18:309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Genevet A, Wehr MC, Brain R, Thompson BJ, Tapon N. Kibra is a regulator of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling network. Dev Cell. 2010;18:300–8. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu J, Zheng Y, Dong J, Klusza S, Deng WM, Pan D. Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Dev Cell. 2010;18:288–99. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grzeschik NA, Parsons LM, Allott ML, Harvey KF, Richardson HE. Lgl, aPKC, and Crumbs regulate the Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway through two distinct mechanisms. Curr Biol. 2010;20:573–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menendez J, Perez-Garijo A, Calleja M, Morata G. A tumor-suppressing mechanism in Drosophila involving cell competition and the Hippo pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14651–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009376107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Dev Biol. 2011;350:139–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z, Hata Y. What is the Hippo pathway? Is the Hippo pathway conserved in Caenorhabditis elegans? J Biochem. 2013;154:207–9. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvt060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hilman D, Gat U. The evolutionary history of YAP and the hippo/YAP pathway. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2403–17. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sebé-Pedrós A, Zheng Y, Ruiz-Trillo I, Pan D. Premetazoan origin of the hippo signaling pathway. Cell Rep. 2012;1:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikmi A, Gaertner B, Seidel C, Srivastava M, Zeitlinger J, Gibson MC. Molecular evolution of the Yap/Yorkie proto-oncogene and elucidation of its core transcriptional program. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1375–90. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia QY, Li S, Feng QL. Advances in silkworm studies accelerated by genome sequencing of Bombyx mori. Annu Rev Entomol. 2014;59:513–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-161940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu S, Zhou S, Tian L, Guo E, Luan Y, Zhang J. et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of ATP-binding cassette transporters in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;32:1792–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56:564–77. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–21. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia Q, Cheng D, Duan J, Wang G, Cheng T, Zha X. et al. Microarray-based gene expression profiles in multiple tissues of the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R162. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hossain MS, Liu Y, Li K, Tian L, Li S. 20-Hydroxyecdysone-induced transcriptional activity of FoxO upregulates brummer and acid lipase-1 and promotes lipolysis in Bombyx fat body. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;43:829–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li K, Guo E, Hossain M, Li Q, Cao Y, Tian L. et al. Bombyx E75 isoforms display stage- and tissue-specific response to 20-hydroxyecdysone. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12114. doi: 10.1038/srep12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Misof B, liu S, Meusemann K, Peters RS, Donath A, Mayer C. et al. Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science. 2014;346:763–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1257570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qi HS, Liu SM, Li S, Wei ZJ. Molecular expression of the Scribble complex genes, Dlg, Scrib and Lgl, in silkworm, Bombyx mori. Genes (Basel) 2013;4:264–74. doi: 10.3390/genes4020264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin VP, Thummel CS. Mechanisms of steroid-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X, Dai F, Guo E, Li K, Ma L, Tian L. et al. E93 transcriptionally modulates 20-hydroxyecdysone signaling during Bombyx larval-pupal metamorphosis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27370–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.687293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma L, Liu S, Shi M, Chen XX, Li S. Ras1CA-upregulated bcpi inhibitis cathepsin activity to prevent tissue destruction of the Bombyx posterior silk gland. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:1924–34. doi: 10.1021/pr400005g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jia SH, Li MW, Zhou B, Liu WB, Zhang Y, Miao XX. et al. Proteomic analysis of silk gland programmed cell death during metamorphosis of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3003–10. doi: 10.1021/pr070043f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma L, Xu H, Zhu J, Ma S, Liu Y, Jiang RJ. et al. Ras1CA overexpression in the posterior silk gland improves silk yield. Cell Res. 2011;21:934–43. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma L, Ma Q, Li X, Cheng L, Li K, Li S. Transcriptomic analysis of differentially expressed genes in the Ras1CA-overexpressed and wildtype posterior silk glands. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheng D, Xia Q, Duan J, Wei L, Huang C, Li Z. et al. Nuclear receptors in Bombyx mori: insights into genomic structure and developmental expression. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:1130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian L, Guo E, Diao Y, Wang S, Liu S, Jiang RJ. et al. Developmental regulation of glycolysis by 20-hydroxyecdysone and juvenile hormone in fat body tissues of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2:255–63. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo E, He Q, Liu S, Tian L, Sheng Z, Peng Q. et al. MET is required for the maximal action of 20-hydroxyecdysone during Bombyx metamorphosis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e53256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tian L, Liu SM, Liu H, Li S. 20-hydroxyecdysone upregulates apoptotic genes and induces apoptosis in the Bombyx fat body. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2012;79:207–19. doi: 10.1002/arch.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tian L, Ma L, Guo E, Deng X, Ma S, Xia Q. et al. 20-hydroxyecdysone upregulates Atg genes to induce autophagy in the Bombyx fat body. Autophagy. 2013;9:1172–87. doi: 10.4161/auto.24731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, Li Z, Xu J, Zeng B, Ling L, You L. et al. The CRISPR/Cas system mediates efficient genome engineering in Bombyx mori. Cell Res. 2013;23:1414–6. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables and figures.