Abstract

Clinical studies indicate that adenosine contributes to esophageal mechanical hypersensitivity in some patients with pain originating in the esophagus. We have previously reported that the esophageal vagal nodose C fibers express the adenosine A2A receptor. Here we addressed the hypothesis that stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor induces mechanical sensitization of esophageal C fibers by a mechanism involving transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1). Extracellular single fiber recordings of activity originating in C-fiber terminals were made in the ex vivo vagally innervated guinea pig esophagus. The adenosine A2A receptor-selective agonist CGS21680 induced robust, reversible sensitization of the response to esophageal distention (10–60 mmHg) in a concentration-dependent fashion (1–100 nM). At the half-maximally effective concentration (EC50: ≈3 nM), CGS21680 induced an approximately twofold increase in the mechanical response without causing an overt activation. This sensitization was abolished by the selective A2A antagonist SCH58261. The adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin mimicked while the nonselective protein kinase inhibitor H89 inhibited mechanical sensitization by CGS21680. CGS21680 did not enhance the response to the purinergic P2X receptor agonist α,β-methylene-ATP, indicating that CGS21680 does not nonspecifically sensitize to all stimuli. Mechanical sensitization by CGS21680 was abolished by pretreatment with two structurally different TRPA1 antagonists AP18 and HC030031. Single cell RT-PCR and whole cell patch-clamp studies in isolated esophagus-specific nodose neurons revealed the expression of TRPA1 in A2A-positive C-fiber neurons and demonstrated that CGS21682 potentiated TRPA1 currents evoked by allylisothiocyanate. We conclude that stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor induces mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers by a mechanism sensitive to TRPA1 antagonists indicating the involvement of TRPA1.

Keywords: vagus nerve, C fibers, nociceptor, adenosine, esophagus

clinical studies have provided evidence that adenosine contributes to noncardiac chest pain originating in the esophagus (1, 8). In these studies, intravenous infusion of adenosine induced esophageal mechanical hyperalgesia characterized by a lowered pain threshold and enhanced pain in response to esophageal distention (34). Similar mechanical hyperalgesia has been observed in many patients with esophageal chest pain (30). Furthermore, the methylxanthine theophylline, which is also a nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist (32), reduced mechanical hyperalgesia in patients with functional chest pain of a presumed esophageal origin (33).

These observations are consistent with the notion that adenosine receptors are involved in the mechanical sensitization of nociceptive pathways in the esophagus. While the location of the relevant adenosine receptors cannot be determined from clinical studies, one plausible explanation is that adenosine acts on the nerve terminals of esophageal nociceptive C fibers. Indeed, we have previously found that the esophageal C fibers express adenosine receptors, namely the adenosine A1 and A2A receptors (36). We noted that adenosine both overtly activates and sensitizes the C fibers. We focus here on the adenosine A2A receptor, which has been previously implicated in hyperalgesia in the somatosensory system and which we have found to be selectively expressed on nodose C fibers (18, 20, 36, 39).

Transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) is a cation channel expressed extensively in nociceptors. TRPA1 mediates sensory transduction of a wide range of noxious chemical stimuli including environmental irritants and inflammatory molecules (17, 29, 41). Intriguingly, TRPA1 has been also implicated in mechanical hypersensitivity (including in the esophagus) and hyperalgesia (4, 10–12, 21, 24, 31, 45, 47). We have reported that TRPA1 stimulation causes a prominent increase in the activity of esophageal nodose C fibers (6). Based on this information we have developed the hypothesis that the stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptors induces sensitization of nodose C fibers by a mechanism involving TRPA1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiments described in this study were approved by the Johns Hopkins Animal Use and Care Committee and/or Jessenius Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee. Male Dunkin Hartley guinea pigs weighing 200–250 g were used.

Extracellular recordings.

Extracellular recordings from vagal neurons innervating the esophagus were performed as previously described (36, 49). Extracellular recordings were made from vagal nodose neurons projecting distention-sensitive C fibers into the esophagus in an isolated, perfused, vagally innervated guinea pig esophagus preparation. The esophagus and trachea were dissected, preserving the bilateral extrinsic vagal innervation (including the nodose ganglia). The tissue was pinned in a small Sylgard-lined Perspex chamber filled with Krebs solution (in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.9 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, and 11 dextrose, gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2, pH 7.4, 35°C) containing indomethacin (3 μM). The esophagus and trachea were pinned in a tissue compartment, and the rostral aspect of the vagus nerves, including the nodose ganglion, was pinned in a recording compartment. The two compartments were separately superfused with Krebs solution (pH 7.4, 35°C, 4–6 ml/min). Polyethylene tubing was inserted 3–5 mm in the cranial and caudal ends of the esophagus and secured for perfusion. Isobaric esophageal distensions with an intraluminal pressure of 10, 30, and 60 mmHg (generated by a gravity-driven pressure system) for 20 s separated by 3 min were used to determine the distension pressure-nerve activity relationship of an esophageal afferent fiber. An aluminosilicate glass microelectrode was filled with a 3-M sodium chloride solution (electrode resistance: 2 MΩ). The electrode was placed in an electrode holder connected directly to the head stage (A-M Systems, Sequim, WA). A return electrode of silver-silver chloride wire and earthed silver-silver chloride pellet was placed in the perfusion fluid of the recording compartment. The recorded signal was amplified (M1800; A-M Systems) and filtered (low cut-off: 0.3k Hz; high cut-off: 1 kHz), and the resultant activity was displayed on an oscilloscope (TDS1001B; Tektronix, Beaverton, OR) and chart recorder. The data were stored and analyzed on an Apple computer using the software TheNerveOfIt (sampling frequency: 33 kHz; PHOCIS, Baltimore, MD). The recording electrode was inserted into the nodose ganglion using a micromanipulator, and a distension-sensitive unit was identified if esophageal distension (to 60 mmHg for 5 s) evoked action potential discharge.

Experimental protocols.

The response to esophageal distension of esophageal nodose C fibers was determined using isobaric esophageal distension with intraluminal pressures of 10, 30, and 60 mmHg for 20 s each separated by 3 min. After the control response to esophageal distention was recorded, the compounds were delivered externally diluted in the Krebs superfusion solution for 30 min. The response to esophageal distention was then recorded in the presence of the compounds. In some experiments, the control response to esophageal distention was repeated to confirm the reproducibility as established in previous studies (5, 49). In experiments designed to evaluate the effect of CGS21680 on the response to distention, two to three concentrations of CGS21680 were evaluated per fiber in threefold increments. In experiments with forskolin, two concentrations were evaluated. In experiments designed to evaluate the effect of the antagonists or inhibitors (SCH58261, H89, AP-18, and HC030031) on the CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization, the response to esophageal distention was first recorded under control conditions, after superfusion with the respective antagonist or inhibitor for 30 min, and then after the perfusion with both the antagonist/inhibitor and CGS21680 for another 30 min. In experiments designed to investigate the effect of CGS21680 on the response to α,β-methylene-ATP, the control response to superfusion of α,β-methylene-ATP (10 min) was recorded, the tissue was superfused with CGS21680 for 30 min, and then the response to superfusion with α,β-methylene-ATP (10 min) was obtained in the presence of CGS21680. The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) agonist capsaicin was used at the end of most experiments at its maximally effective concentration of 1 μM to confirm capsaicin responsiveness of the nodose C fibers. Only 4 out of 88 nodose C fibers in this study were capsaicin-insensitive and these fibers were not included in the analysis.

Extracellular recording data analysis.

The nerve activity (action potential discharge) was monitored continuously throughout the experiments. The response to distention was quantified as the total number of action potentials during the 20-s distention period presented as means ± SE. For statistical analysis of the change in the overall response to distention, the area under the curve (AUC) was used as described previously (46). AUC was calculated using standard geometrical formulas with the resultant formula (units omitted): AUC = 20 × (T10 + T30)/2 + 30 × (T30 + T60)/2, where T10, T30, and T60 are the total number of action potentials at the distention pressures 10, 30, and 60 mmHg, respectively, and the coefficients 20 and 30 refer to difference between the tested pressures (i.e., 20 mmHg = 30-10 mmHg). The AUC was determined under control conditions and following the treatment(s). In addition, the peak frequency of distention-induced action potential discharge was also quantified and is presented as means ± SE. The fold increase in mechanical response for CGS21680 concentration-mechanical sensitization curve presented in results (see Fig. 2A) was calculated by dividing the response to distention with 30 mmHg in the presence of the indicated concentration of CGS21680 by the control response. In the three instances when the response to 30 mmHg was too small (<3 action potentials), the response to 60 mmHg was used instead. The activation (overt action potential discharge) evoked by compound superfusion was monitored was quantified as maximum discharge in 60-s bin defined as the maximal number of action potentials recorded in any 60-s interval during the superfusion with the drug. Acid (pH 5.3) was prepared by modification of Krebs solution by substitution of bicarbonate with phosphates and by adding Na d-gluconate to maintain sodium concentration and osmolarity as follows (in mM): 118 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 6 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.9 CaCl2, 11 dextrose, and 19 Na d-gluconate, with pH adjusted to 5.3 if needed. ANOVA, paired t-tests, and unpaired t-tests were used as was appropriate, and the significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers by CGS21680 is mediated by the A2A receptor. A: concentration-response curve of CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization in esophageal nodose C fibers. The fold increase of response was calculated by dividing the response to distention (30 mmHg) after and before pretreatment with CGS21680. B: selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist SCH58261 completely and reversibly inhibited CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization in esophageal nodose C fibers (n = 5). C: representative traces of action potential discharge evoked by esophageal distention (30 mmHg, 20 s) in the presence of SCH58261 before and after pretreatment with CGS21680.

Retrograde labeling.

Retrograde labeling of the afferent neurons projecting to the guinea pig esophagus was performed as described previously (36, 48). In brief, ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) were given (ip) as anesthesia, the cervical esophagus was surgically exposed, and the retrograde tracer DiI (0.1% in 10% DMSO in sterile saline; total volume: 5–10 μl) was injected into the esophageal wall (1–2 sites). Following injection the esophageal surface was washed with a swab.

Dissociation.

The vagal nodose ganglia were harvested 10–15 days after esophageal DiI injections. Single cell RT-PCR studies were performed on individual neurons as described previously (25, 36, 38). The sensory ganglia were dissected and incubated in the enzyme buffer (2 mg/ml collagenase type 1A and 2 mg/ml and dispase II in Ca2+ and Mg2+ free HBSS) for 3 × 15 min at 37°C. Neurons were dissociated by trituration with three glass Pasteur pipettes of decreasing tip pore size between and after incubations. Then, they were washed by centrifugation (3 times at 1,000 g for 2 min) and suspended in l-15 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (L-15/FBS). The cell suspension was transferred onto poly-d-lysine/laminin-coated coverslips. After the suspended neurons had adhered to the coverslips for 2 h, the neuron-attached coverslips were flooded with L-15/FBS and used within 8 h.

Neuron picking.

Coverslips with dissociated neurons were perfused with PBS, and the DiI-labeled neurons were identified under fluorescent microscope (rhodamine filter). Neurons were individually harvested by applying negative pressure to a glass-pipette (tip: 50–150 μm) pulled with a micropipette puller (P-87; Sutter). The pipette tip containing the cell was broken into a PCR tube containing RNAse inhibitor (1 μl; RNAseOUT, 2Ul-1; Invitrogen), immediately frozen and stored at −80°C. Only the neurons free of debris or attached cells were collected. One to five cells were collected from each coverslip. A sample of the bath solution was collected from some coverslips for no-template experiments (bath control).

Single cell RT-PCR.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from single neurons by using the Super-Script(tm) III CellsDirect cDNA Synthesis System (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Samples were defrosted, lysed (10 min, 75°C), and treated with DNAse I. Then, poly(dT) and random hexamer primers (Roche Applied Bioscience) were added. The samples were reverse transcribed by adding SuperscriptIII RT for cDNA synthesis. Two microliters of each sample (cDNA, RNA control, or bath control, respectively) were used for PCR amplification by the HotStar Taq Polymerase Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations in a final volume of 20 μl. After an initial activation step of 95°C for 15 min, cDNAs were amplified with custom-synthesized primers (Life Technologies) by 50 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Products were visualized in ethidum-bromide stained 1.5% agarose gels with a 50- or 100-bp DNA ladder. Figures (scRT-PCR) were prepared from multiple original gel images (from which only the C-fiber TRPV1-positive neurons were selected) by using Microsoft PowerPoint and Apple Preview. The bends indicate only the presence or absence of a product (i.e., target expression) but not the intensity of expression. The expression of TRPA1 was analyzed in the nodose TRPV1-positive neurons in which we had previously reported TRPV1 and A2A expression (36). The primers were designed by using Primer3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/primer3/) (35). TRPV1 primers (sequence NM_001172652.1) were as follows: forward primer, CCAACAAGAAGGGGTTCACA; reverse primer, ACAGGTCATAGAGCGAGGAG; predicted product size: 168 bp; and predicted genomic product: >1,000 bp. A2A primers (sequence NM_001172733.1) were as follows: forward, CATCCCCTTCGCTATCACC; reverse, GCTGGCTTTCCATTTGTTTC; product size: 467 bp; and predicted genomic product: >1,000 bp. TRPA1 primers (sequence NM_001198770.1) were as follows: forward, TTAGCAACTGCCTCTGCATC; reverse, TACCAGCGCCTTGATCTCTT; product size: 177 bp; and predicted genomic product: >1,000 bp. The primers are intron-spanning and no genomic product would be amplified (size >1,000 bp is not achievable with the extension time of 30 s used for PCR), thus preventing false positive detection.

Whole cell patch clamp.

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings from nodose neurons were performed according to our previously described method (15). Briefly, borosilicate glass (WPI, Sarasota, FL) pipettes were pulled to 2–3 MΩ and filled with the pipette solution (in mM): 140 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 MgATP, 2 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 with CsOH). Whole cell patch clamp was performed using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier and Axograph software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, now Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Currents were typically digitized at 10 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. During the experiments, the cells were continuously superfused with extracellular solution (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH) at room temperature. Drugs were delivered in the superfusion solution as follows: allyl isothiocyanate (AITC; 100 μM, 60 s), CGS21680 (10 nM, 60 s), and a combination of AITC (100 μM) and CGS21680 (10 nM) for 60 s. In some experiments the response to repeated AITC was obtained. The data are presented as means ± SE of inward current density (inward current normalized for the cell capacitance, pA/pF).

Drugs and chemicals.

The following drugs were used: CGS21680 (stock solution 10 mM dissolved in DMSO; Tocris Bioscience); AP-18 (stock 100 mM in DMSO; Tocris Bioscience), SCH58261 (stock 10 mM in DMSO; Tocris Bioscience), HC030031 (100 mM in DMSO; Tocris Bioscience), α,β-methylene-ATP (stock 10 mM in water; Sigma-Aldrich), forskolin (stock 100 mM in DMSO; Tocris Bioscience), H89 (stock 10 mM in water; Tocris Bioscience), capsaicin (stock 10 mM in ethanol; Sigma-Aldrich), and AITC (stock 0.1 M in DMSO). Stock solutions were stored at −20°C. All drugs were further diluted in Krebs solution to indicated final concentrations shortly before use.

RESULTS

Eighty-four nodose C fibers with nerve terminals in the esophagus that responded to esophageal distention were studied (1 C fiber/animal). We found that the selective adenosine A2A receptor agonist CGS21680 evoked mechanical sensitization in esophageal nodose C fibers. Pretreatment with CGS21680 (3 nM, 30 min) induced a robust increase in the response evoked by esophageal distention with 10–60 mmHg (Fig. 1). Both the total number of action potentials as well as the peak frequency of action potential discharge evoked by 20 s of distention were approximately doubled (Fig. 1, B–D). The typical time course of distention-evoked action potential discharge in nodose C fibers, consisting of a large increase in firing during the dynamic phase of distention followed by smaller nonadapting discharge (48), was not altered (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The adenosine A2A receptor selective agonist CGS21680 induced sensitization of the mechanical response to esophageal distention in nodose C fibers. A and B: representative traces and averaged time course of action potential discharge evoked by esophageal distention (20 s) before and after pretreatment with CGS21680 (3 nM, n = 10). A, insets: action potential shape. C and D: total number and peak frequency of action potential discharge evoked by esophageal distention in two control stimulations and after pretreatment with CGS21680 (3 nM, n = 10). Note the reproducibility of the response induced by esophageal distention. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The mechanical sensitization induced by CGS21680 was concentration dependent. Figure 2 shows that the maximally effective concentration of CGS21680 was 30–100 nM, and the EC50 was ∼3 nM. The sensitizing effect of CGS21680 was fully reversible after washout. In experiments designed to investigate the reversibility of CGS21680-induced sensitization, the number of action potentials evoked by esophageal distention to 30 mmHg was 11 ± 4 at baseline, 20 ± 6 after 30 min of superfusion with CGS21680 (100 nM), and 10 ± 3 after 30 min of washout (n = 4).

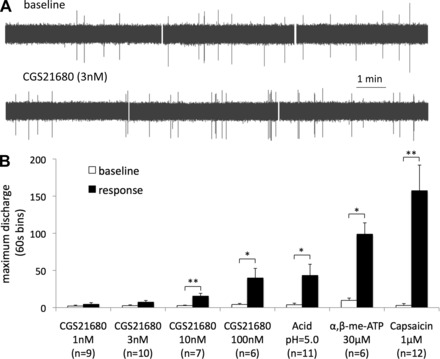

We then used the selective A2A antagonist SCH58261 to evaluate the selectivity of CGS21680 for the A2A receptor on the nodose C fibers in our system (13, 51). Pretreatment with SCH58261 (0.1 μM, 30 min) did not affect the mechanical response in nodose C fibers but prevented CGS21680 (3 nM, 30 min)-induced mechanical sensitization (Fig. 2B). CGS21680 was able to induce sensitization 30 min after SCH58261 was discontinued indicating that the inhibition of CGS21680 by SCH58261 was reversible (Fig. 2B). The concentration-dependency and the inhibition by SCH58261 indicate that the CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization in esophageal nodose C fibers is mediated by the adenosine A2A receptor. Based on these results, we chose to use CGS21680 in the concentration of 3 nM for subsequent studies. Even though it effectively sensitized the mechanical response, CGS21680 was relatively ineffective in inducing action potential discharge in esophageal nodose C fibers (Fig. 3). For example, CGS21680 in the concentration of 3 nM that induced a doubling in the mechanical response (Fig. 1) evoked almost no action potential discharge over baseline (Fig. 3). This shows that the stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor can induce sensitization of nodose C fibers without causing an overt activation.

Fig. 3.

Stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor can induce a robust sensitization without causing an overt activation in nodose C fibers. Note that CGS21680 (3 nM) induced a strong sensitization (Fig. 1) and failed to cause an overt action potential discharge. A: examples of traces of baseline activity and the activity following the superfusion with CGS21680. B: maximum activity expressed per 60-s bin. Acid, the P2X receptor agonist α,β-methylene-ATP (α,β-me-ATP), and the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptor agonist capsaicin are included for comparison as stimuli that strongly activate nodose C fibers. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 response vs. baseline.

We next addressed the question of whether the mechanical sensitization induced by CGS21680 is due to a nonselective increase in nodose C-fiber excitability. We used the purinergic P2X receptors agonist α,β-methylene-ATP, which evokes a reproducible action potential discharge in nodose C fibers (46, 49). In contrast to its effect on mechanical sensitization, CGS21680 did not enhance the response of nodose C fibers to α,β-methylene-ATP. The peak frequency of the response to α,β-methylene-ATP (30 μM, 10 min) remained unchanged following the pretreatment with CGS21680 (3 nM, 30 min) (5 ± 1 vs. 5 ± 1 Hz, respectively, P > 0.5). For comparison, the peak frequency of the distention (30 mmHg)-induced action potential discharge in the same experiments was doubled from 5 ± 1 to 11 ± 2 Hz (P < 0.05, n = 6). No sensitization was revealed when the overall response to α,β-methylene-ATP was quantified (maximum activity expressed per 60-s bin was 99 ± 15 vs. 93 ± 12 action potentials, P > 0.5, n = 6). These results indicate that the stimulation of the A2A does not nonspecifically increase the responsiveness of nodose C fibers to all stimuli.

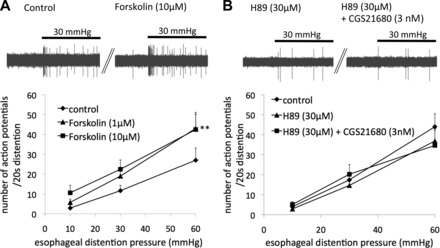

In most cell types the adenosine A2A receptor has been reported to couple to the Gs protein leading to adenylate cyclase and protein kinase A (PKA) activation (13, 32). We investigated whether the pharmacological tools that modulate the Gs-adenylate cyclase-PKA pathway would influence the mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers induced by CGS21680. Similarly to CGS21680, the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin (1–10 μM) induced sensitization of response to esophageal distention (Fig. 4A). Also similarly to CGS21680, forskolin did not induce appreciable action potential discharge in nodose C fibers (the forskolin-induced activation was comparable to CGS21680 3–10 nM in Fig. 3B). The nonselective kinase inhibitor H89, which also inhibits PKA, inhibited CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization (Fig. 4B). These results are consistent with the involvement of the Gs-adenylate cyclase-PKA pathway in the CGS21680-induced sensitization.

Fig. 4.

Modulators of the adenylate cyclase-protein kinase A pathway influence mechanical sensitivity of nodose C fibers. A: adenylate cyclase activator forskolin enhanced the mechanical response of nodose C fibers (n = 7, **P < 0.01 forskolin 10 μM vs. control). Inset: examples of action potential discharge evoked by esophageal distention (30 mmHg, 20 s) before and after pretreatment with forskolin. B: protein kinase inhibitor H89 inhibited CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization (n = 9, P = 0.8). Inset: examples of action potential discharge evoked by esophageal distention (30 mmHg, 20 s) in the presence of H89 before and after pretreatment with CGS21680.

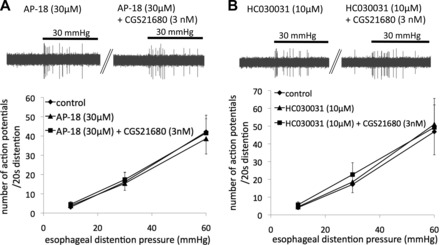

The TRPA1 channel has been implicated in mechanical sensitization of somatosensory and visceral afferent nerves including the esophageal C fibers (4, 24, 47). We therefore evaluated the effect of TRPA1 antagonists on mechanical sensitization evoked by CGS21680. We used the TRPA1 antagonist AP-18 (30 μM), which completely abolished activation of esophageal nodose C fibers by AITC (100 μM) (6, 31). Pretreatment with AP-18 did not affect the control response to mechanical distention but completely abolished the mechanical sensitization evoked by CGS21680 (Fig. 5A). In addition, pretreatment with another TRPA1 antagonist, HC030031 (10 μM) (11), did not affect the mechanical response but virtually abolished the mechanical sensitization by CGS21680. These results indicate that the activation of the A2A receptor evokes mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers by modulating TRPA1. TRPA1 antagonists did not have any effect on the action potential discharge during the perfusion with CGS21680. In the presence of AP18 (30 μM, n = 13), the maximum discharge in a 60-s bin was 5.5 ± 2.0 vs. 11.6 ± 4.8, under control conditions and during CSG21680 perfusion (3 nM), respectively (P = 0.07). In the presence of HC030031 (10 μM, n = 7), the maximum discharge in 60 s was 7.6 ± 3.0 vs. 12.9 ± 4.6 (P = 0.07), which was similar to the spontaneous firing during the perfusion with CGS21680 alone (Fig. 3).

Fig. 5.

Mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers induced by CGS21680 was abolished by transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) antagonists. Pretreatment with the selective TRPA1 antagonist AP-18 (n = 13; A) and HC030031 (n = 7; B) prevented CGS21680 from sensitizing nodose C fibers. A, inset: examples of action potential discharge evoked by esophageal distention (30 mmHg, 20 s) in the presence of AP-18 before and after pretreatment with CGS21680. B, inset: examples of action potential discharge evoked by esophageal distention (30 mmHg, 20 s) in the presence of HC030031 before and after pretreatment with CGS21680.

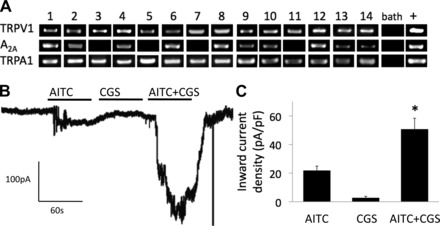

In a complex tissue-nerve preparation, CGS21680 could potentially be acting indirectly to induce mechanical sensitization of C fibers by causing release of sensitizing mediators from other cell types. Therefore, we investigated whether CGS21680 can induce the sensitization of TRPA1 in isolated esophageal nodose C-fiber neurons. Consistent with the predictions from our previous studies (6, 36), we showed that esophageal C-fiber (TRPV1-positive) neurons expressing A2A also express TRPA1 (Fig. 6A). We next studied the esophageal nodose C-fiber (AITC-responsive) neurons by performing whole cell patch-clamp recordings in voltage clamp mode. In a manner consistent with our extracellular studies (Fig. 3), we found that CGS21680 did not induce appreciable currents in C-fiber neurons (Fig. 6, B and C). However, we found that CGS21680 induced a twofold enhancement of AITC-induced currents (Fig. 6, B and C). This is consistent with the hypothesis that CGS21680 induces mechanical sensitization via the TRPA1 receptor, thus providing evidence that CGS21680 can induce TRPA1 sensitization in the nodose C fibers.

Fig. 6.

Sensitization of TRPA1 by CGS21680 in isolated esophageal C-fiber neurons. A: expression of the adenosine A2A receptor and the TRPA1 channel in esophageal nodose C-fiber neurons. Single cell RT-PCR was performed on TRPV1-positive nodose neurons retrogradely labeled from the esophagus. Individual neurons are numbered. “Bath” refers to a sample of the superfusing fluid (negative control); “+” refers to a sample from the total RNA from the whole ganglia (positive control). The bands indicate only the presence of the target, but not the intensity of expression. B and C: CGS21680 (CGS, 10 nM) potentiated the currents induced by the TRPA1 agonist AITC (100 μM) in esophageal nodose neurons (n = 6, *P < 0.05). The whole cell patch-clamp recordings were made from the nodose neurons retrogradely labeled from the esophagus. Only neurons that responded to AITC were studied (5 AITC-unresponsive neurons were not studied further).

DISCUSSION

We found that stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor in esophageal nodose C fibers induces robust mechanical sensitization without causing overt activation. In contrast to sensitization of the mechanical response, the response evoked by P2X receptors agonist was not affected, indicating that the mechanical sensitization was not due to a nonspecific increase in sensitivity to all stimuli. Pharmacological inhibition of mechanical sensitization by TRPA1 agonists is consistent with the hypothesis that mechanical sensitization induced by A2A stimulation in nodose C fibers is mediated by TRPA1. This hypothesis is indirectly supported by studies in the isolated neurons showing that stimulation of the A2A receptor can sensitize TRPA1 currents in esophageal nodose C fibers. We have also provided evidence consistent with the involvement of the Gs-protein-adenylate cyclase-PKA pathway in the mechanical sensitization induced by the adenosine A2A receptor.

We conclude that mechanical sensitization induced by CGS21680 in nodose C fibers is mediated by the adenosine A2A receptor. This conclusion is supported by the high potency (EC50: ≈3 nM) and concentration dependency of CGS21680, the reversibility of CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization, and the complete and reversible inhibition of CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization by the selective A2A receptor antagonist SCH58261.

In our experiments, the potency of CGS21680 on the A2A receptor was similar to that reported in other systems (3, 26, 43, 51). We have previously shown that of the four known adenosine receptors, nodose C fibers express the adenosine A1 and A2A receptors but not A2B and A3 receptors (36). Previous studies in the guinea pig vagal C fibers have also shown that the effects of CGS21680 (up to 100 nM) were not affected by the selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX, indicating that CGS21680 does not induce appreciable effects in this system through A1 receptor (9). The concentration of SCH58261 selected for our experiments (0.1 μM) was shown to block the effect of CGS21680 but not effect of the selective A1 receptor agonist CCPA in the guinea pig vagal C fibers (9). The observation that the A2A receptor induced mechanical sensitization is consistent with the finding that local stimulation of adenosine A2A receptors induced mechanical hyperalgesia in the skin (20, 39).

Although CGS21680 enhanced the response to esophageal distention, it did not affect the response evoked by the P2X receptors agonist α,β-methylene-ATP. This is consistent with the hypothesis that CGS21680 does not nonspecifically increase sensitivity to all stimuli. In theory, the lack of enhancement of the response to α,β-methylene-ATP could be observed if near-maximum stimulation was achieved by α,β-methylene-ATP under control conditions. However, the peak frequency of the control response to α,β-methylene-ATP (≈5 Hz) was similar to the peak frequency of the response induced by 30 mmHg of distention (≈5 Hz) in the same set of C fibers. Nonetheless, while the response to α,β-methylene-ATP was not affected by CGS21680, the response to distention was approximately doubled (peak: ≈11 Hz) in paired experiments. These results indicate that the increase in mechanical sensitivity of the nodose C fibers caused by stimulation of the adenosine A2A receptor is not attributable to a nonspecific increase in electrical excitability.

We found that the sensitization induced by CGS21680 was prevented by the two structurally unrelated TRPA1 antagonists AP18 and HC030031. These data indicate that TRPA1 plays a key role in the CGS21680-induced mechanical sensitization in nodose C fibers. Our findings are in agreement with previous reports that TRPA1 mediates mechanical sensitization induced by inflammatory mediators and by inflammation in certain subsets of somatic and visceral afferent nerves (4, 24), including the esophageal C fibers (45, 47). The role of TRPA1 in mechanical hyperalgesia (behavioral mechanical hypersensitivity) has been demonstrated in a number of organ systems (10–12, 21, 31). To our knowledge, the mechanism by which TRPA1 contributes to mechanical sensitization of afferent nerves has not been elucidated.

We also observed that TRPA1 antagonists did not inhibit distention-induced activation of nodose C fibers under control conditions. The selective TRPA1 antagonist AP-18 (30 μM) completely abolished activation by AITC (100 μM) (6) but had no effect on the response to esophageal distention (Fig. 5A). These data are similar to previous reports (45, 47), and indicate that TRPA1 does not participate in normal mechanotransduction of esophageal distention in nodose C fibers. Intriguingly, while in some nerve types TRPA1 contributed to response to focal mechanical stimuli (exemplified by stimulation with a von Frey probe) (4, 19, 22), it has not been found to participate in response to distention/stretch in naïve animals without inflammation or application of sensitizing mediators. A notable example of this difference is pelvic muscular/mucosal fibers innervating the colon, in which the knockout of TRPA1 dramatically reduced the response to von Frey probes but did not affect response to distention (4). The mechanism of how mechanical forces lead to TRPA1 activation has not been determined.

With a few exceptions, the adenosine A2A receptor couples to a Gs protein that stimulates adenylate cyclase, leading to an increase in cAMP and PKA activation (13, 32). We carried out two experiments that could challenge the notion that CGS21680-induced sensitization is mediated by the Gs-adenylate cyclase-PKA pathway. In these experiments, the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin mimicked the effect of CGS21680, and the kinase inhibitor H89 abolished the mechanical sensitization induced by CGS21680 (Fig. 4). Although this is not sufficient to implicate a specific pathway, these results are consistent with the involvement of the Gs-adenylate cyclase-PKA pathway. Previous studies have also indicated that TRPA1 can be sensitized by PKA (44). Interestingly, one study reported that the activators of PKA (dibutryl cAMP and forskolin) enhanced the response to heat but not the response to bradykinin in visceral polymodal nociceptors (28). This is similar to the selectivity of sensitization we noted here.

Our data indicate that stimulation of adenosine A2A receptors leads to sensitization of TRPA1 such that the TRPA1 becomes a meaningful component of the mechanical response. Furthermore, we hypothesized that this A2A-TRPA1 interaction occurs directly at the level of the nerve terminals in the absence of secondary influences such as autacoids released by other cell types in the esophageal tissue. This hypothesis receives indirect support from our observation that esophageal nodose C-fiber neurons coexpress mRNA for TRPA1 and adenosine A2A receptors. In addition, this idea is consistent with our finding that A2A activation enhances TRPA1 currents in individual isolated nodose C-fiber neurons in the whole cell patch-clamp studies. These results also suggest that stimulation of adenosine A2A receptor will amplify the activation of TRPA1 by endogenous activators in the esophagus such as the products of oxidative and nitrosative stress (2, 27, 40) induced by refluxed acid (14, 16) or reactive molecules commonly produced by immune cells (42).

Previous studies have shown that the mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers induced by stimulation of bradykinin B2 receptor and protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) was blocked by the TRPA1 antagonist (45, 47). PAR2 and the bradykinin B2 receptor most commonly activate the Gq-phospholipase Cβ-protein kinase C pathway but can also activate the Gs-adenylate cyclase-PKA pathway, the G12/13-Rho-kinase pathway, and other signaling pathways (23, 50). One possible scenario is that multiple pathways converge to cause mechanical sensitization via TRPA1. Alternatively, the bradykinin B2 receptor, PAR2, and the adenosine A2A receptor could cause mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers via activation of the same pathway, most likely through the Gs-adenylate cyclase-PKA pathway. Irrespective of the signaling pathway involved, the observation that mechanical sensitization of nodose C fibers by multiple mediators can be blocked by inhibiting TRPA1 provides further support for the integrating aspect of TRPA1 in esophageal mechanical nociception and potential drug target (29).

The source of adenosine in patients with esophageal hyperalgesia and chest pain has not been determined. Adenosine can be released from a variety of cell types activated by inflammation including neurons, endothelial cells, neutrophils, mast cells, and fibroblasts (37). Another potential source of adenosine is ATP that is converted to adenosine by nucleotidases (e.g., ecto-5′-nucleotidase). Importantly, in addition to inflammation, ATP can be released from epithelial and smooth muscle cells by mechanical forces (7) such as the forces associated with swallowing. If adenosine is released in the vicinity of nodose C-fiber terminals, it would be predicted to cause the A2A-mediated mechanical sensitization via TRPA1 that may contribute to pain in some patients with esophageal diseases.

GRANTS

This study was supported by BioMed Martin (ITMS: 26220220187) cofunded by the European Union (Slovakia) and Department of Education Grant VEGA 1/0070/15 (Slovakia). Support was also provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-074480 (to M. Kollarik) and DK-087991 (to S. Yu).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.B. and M.K. conception and design of research; M.B., L.M., F.R., and Y.H. performed experiments; M.B., L.M., F.R., M.T., Y.H., and S.Y. analyzed data; M.B., M.T., S.Y., and M.K. interpreted results of experiments; M.B. and M.K. drafted manuscript; M.B., L.M., F.R., M.T., Y.H., S.Y., and M.K. approved final version of manuscript; M.T. and M.K. edited and revised manuscript; Y.H. and M.K. prepared figures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Adam Herbstsomer for careful proofreading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achem SR. New frontiers for the treatment of noncardiac chest pain: the adenosine receptors. Am J Gastroenterol 102: 939–941, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson DA, Gentry C, Moss S, Bevan S. Transient receptor potential A1 is a sensory receptor for multiple products of oxidative stress. J Neurosci 28: 2485–2494, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balwierczak JL, Sharif R, Krulan CM, Field FP, Weiss GB, Miller MJ. Comparative effects of a selective adenosine A2 receptor agonist, CGS 21680, and nitroprusside in vascular smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol 196: 117–123, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brierley SM, Hughes PA, Page AJ, Kwan KY, Martin CM, O'Donnell TA, Cooper NJ, Harrington AM, Adam B, Liebregts T, Holtmann G, Corey DP, Rychkov GY, Blackshaw LA. The ion channel TRPA1 is required for normal mechanosensation and is modulated by algesic stimuli. Gastroenterology 137: 2084–2095, e2083, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brozmanova M, Mazurova L, Tatar M, Kollarik M. Evaluation of the effect of GABA(B) agonists on the vagal nodose C-fibers in the esophagus. Physiol Res 62: 285–295, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brozmanova M, Ru F, Surdenikova L, Mazurova L, Taylor-Clark T, Kollarik M. Preferential activation of the vagal nodose nociceptive subtype by TRPA1 agonists in the guinea pig esophagus. Neurogastroenterol Motil 23: e437–e445, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnstock G. Purinergic mechanosensory transduction and visceral pain. Mol Pain 5: 69, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chahal PS, Rao SS. Functional chest pain: nociception and visceral hyperalgesia. J Clin Gastroenterol 39: S204–209; discussion S210, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuaychoo B, Lee MG, Kollarik M, Pullmann R Jr, Undem BJ. Evidence for both adenosine A1 and A2A receptors activating single vagal sensory C-fibres in guinea pig lungs. J Physiol 575: 481–490, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Costa DS, Meotti FC, Andrade EL, Leal PC, Motta EM, Calixto JB. The involvement of the transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) in the maintenance of mechanical and cold hyperalgesia in persistent inflammation. Pain 148: 431–437, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eid SR, Crown ED, Moore EL, Liang HA, Choong KC, Dima S, Henze DA, Kane SA, Urban MO. HC-030031, a TRPA1 selective antagonist, attenuates inflammatory- and neuropathy-induced mechanical hypersensitivity. Mol Pain 4: 48, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes ES, Russell FA, Spina D, McDougall JJ, Graepel R, Gentry C, Staniland AA, Mountford DM, Keeble JE, Malcangio M, Bevan S, Brain SD. A distinct role for transient receptor potential ankyrin 1, in addition to transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced inflammatory hyperalgesia and Freund's complete adjuvant-induced monarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 63: 819–829, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredholm BB, APIJ, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 53: 527–552, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harnett KM, Rieder F, Behar J, Biancani P. Viewpoints on Acid-induced inflammatory mediators in esophageal mucosa. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 16: 374–388, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Y, Liu Z, Yu X, Pasricha PJ, Undem BJ, Yu S. Increased acid responsiveness in vagal sensory neurons in a guinea pig model of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 307: G149–G157, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iijima K, Henry E, Moriya A, Wirz A, Kelman AW, McColl KE. Dietary nitrate generates potentially mutagenic concentrations of nitric oxide at the gastroesophageal junction. Gastroenterology 122: 1248–1257, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Julius D. TRP channels and pain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 29: 355–384, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsten R, Gordh T, Post C. Local antinociceptive and hyperalgesic effects in the formalin test after peripheral administration of adenosine analogues in mice. Pharmacol Toxicol 70: 434–438, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerstein PC, del Camino D, Moran MM, Stucky CL. Pharmacological blockade of TRPA1 inhibits mechanical firing in nociceptors. Mol Pain 5: 19, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khasar SG, Wang JF, Taiwo YO, Heller PH, Green PG, Levine JD. Mu-opioid agonist enhancement of prostaglandin-induced hyperalgesia in the rat: a G-protein beta gamma subunit-mediated effect? Neuroscience 67: 189–195, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondo T, Obata K, Miyoshi K, Sakurai J, Tanaka J, Miwa H, Noguchi K. Transient receptor potential A1 mediates gastric distention-induced visceral pain in rats. Gut 58: 1342–1352, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan KY, Glazer JM, Corey DP, Rice FL, Stucky CL. TRPA1 modulates mechanotransduction in cutaneous sensory neurons. J Neurosci 29: 4808–4819, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leeb-Lundberg LM, Marceau F, Muller-Esterl W, Pettibone DJ, Zuraw BL. International Union of Pharmacology. XLV. Classification of the kinin receptor family: from molecular mechanisms to pathophysiological consequences. Pharmacol Rev 57: 27–77, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lennertz RC, Kossyreva EA, Smith AK, Stucky CL. TRPA1 mediates mechanical sensitization in nociceptors during inflammation. PLoS One 7: e43597, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q, Tang Z, Surdenikova L, Kim S, Patel KN, Kim A, Ru F, Guan Y, Weng HJ, Geng Y, Undem BJ, Kollarik M, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ, Dong X. Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell 139: 1353–1365, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin PL, May JM. Identification and functional characterization of A1 and A2 adenosine receptors in the rat vas deferens: a comparison with A1 receptors in guinea pig left atrium and A2 receptors in guinea pig aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 269: 1228–1235, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyamoto T, Dubin AE, Petrus MJ, Patapoutian A. TRPV1 and TRPA1 mediate peripheral nitric oxide-induced nociception in mice. PLoS One 4: e7596, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizumura K, Koda H, Kumazawa T. Opposite effects of increased intracellular cyclic AMP on the heat and bradykinin responses of canine visceral polymodal receptors in vitro. Neurosci Res 25: 335–341, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran MM, McAlexander MA, Biro T, Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10: 601–620, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasr I, Attaluri A, Hashmi S, Gregersen H, Rao SS. Investigation of esophageal sensation and biomechanical properties in functional chest pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil 22: 520–526, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrus M, Peier AM, Bandell M, Hwang SW, Huynh T, Olney N, Jegla T, Patapoutian A. A role of TRPA1 in mechanical hyperalgesia is revealed by pharmacological inhibition. Mol Pain 3: 40, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 50: 413–492, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao SS, Mudipalli RS, Mujica V, Utech CL, Zhao X, Conklin JL. An open-label trial of theophylline for functional chest pain. Dig Dis Sci 47: 2763–2768, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Remes-Troche JM, Chahal P, Mudipalli R, Rao SS. Adenosine modulates oesophageal sensorimotor function in humans. Gut 58: 1049–1055, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rozen S, Skaletsky J. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology, edited by Krawetz S, Misener S. Totowa, Canada: Humana, 2000, p. 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ru F, Surdenikova L, Brozmanova M, Kollarik M. Adenosine-induced activation of esophageal nociceptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G485–G493, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawynok J, Liu XJ. Adenosine in the spinal cord and periphery: release and regulation of pain. Prog Neurobiol 69: 313–340, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Surdenikova L, Ru F, Nassenstein C, Tatar M, Kollarik M. The neural crest- and placodes-derived afferent innervation of the mouse esophagus. Neurogastroenterol Motil 24: e517–525, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taiwo YO, Levine JD. Direct cutaneous hyperalgesia induced by adenosine. Neuroscience 38: 757–762, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi N, Mizuno Y, Kozai D, Yamamoto S, Kiyonaka S, Shibata T, Uchida K, Mori Y. Molecular characterization of TRPA1 channel activation by cysteine-reactive inflammatory mediators. Channels (Austin) 2: 287–298, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor-Clark TE, Nassenstein C, McAlexander MA, Undem BJ. TRPA1: A potential target for anti-tussive therapy. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 22: 71–74, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor-Clark TE, Undem BJ, Macglashan DW Jr, Ghatta S, Carr MJ, McAlexander MA. Prostaglandin-induced activation of nociceptive neurons via direct interaction with transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1). Mol Pharmacol 73: 274–281, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vials A, Burnstock G. A2-purinoceptor-mediated relaxation in the guinea-pig coronary vasculature: a role for nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol 109: 424–429, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S, Dai Y, Fukuoka T, Yamanaka H, Kobayashi K, Obata K, Cui X, Tominaga M, Noguchi K. Phospholipase C and protein kinase A mediate bradykinin sensitization of TRPA1: a molecular mechanism of inflammatory pain. Brain 131: 1241–1251, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu S, Gao G, Peterson BZ, Ouyang A. TRPA1 in mast cell activation-induced long-lasting mechanical hypersensitivity of vagal afferent C-fibers in guinea pig esophagus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G34–G42, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu S, Kollarik M, Ouyang A, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Mast cell-mediated long-lasting increases in excitability of vagal C-fibers in guinea pig esophagus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G850–G856, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu S, Ouyang A. TRPA1 in bradykinin-induced mechanical hypersensitivity of vagal C fibers in guinea pig esophagus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296: G255–G265, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu S, Ru F, Ouyang A, Kollarik M. 5-Hydroxytryptamine selectively activates the vagal nodose C-fibre subtype in the guinea-pig oesophagus. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20: 1042–1050, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu S, Undem BJ, Kollarik M. Vagal afferent nerves with nociceptive properties in guinea-pig oesophagus. J Physiol 563: 831–842, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao P, Metcalf M, Bunnett NW. Biased signaling of protease-activated receptors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: 67, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zocchi C, Ongini E, Conti A, Monopoli A, Negretti A, Baraldi PG, Dionisotti S. The non-xanthine heterocyclic compound SCH 58261 is a new potent and selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 276: 398–404, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]