Abstract

The mechanism of the nearly universal decreased muscle strength in cirrhosis is not known. We evaluated whether hyperammonemia in cirrhosis causes contractile dysfunction independent of reduced skeletal muscle mass. Maximum grip strength and muscle fatigue response were determined in cirrhotic patients and controls. Blood and muscle ammonia concentrations and grip strength normalized to lean body mass were measured in the portacaval anastomosis (PCA) and sham-operated pair-fed control rats (n = 5 each). Ex vivo contractile studies in the soleus muscle from a separate group of Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 7) were performed. Skeletal muscle force of contraction, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation were measured. Muscles were also subjected to a series of pulse trains at a range of stimulation frequencies from 20 to 110 Hz. Cirrhotic patients had lower maximum grip strength and greater muscle fatigue than control subjects. PCA rats had a 52.7 ± 13% lower normalized grip strength compared with control rats, and grip strength correlated with the blood and muscle ammonia concentrations (r2 = 0.82). In ex vivo muscle preparations following a single pulse, the maximal force, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation were 12.1 ± 3.5 g vs. 6.2 ± 2.1 g; 398.2 ± 100.4 g/s vs. 163.8 ± 97.4 g/s; −101.2 ± 22.2 g/s vs. −33.6 ± 22.3 g/s in ammonia-treated compared with control muscle preparation, respectively (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). Tetanic force, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation were depressed across a range of stimulation from 20 to 110 Hz. These data provide the first direct evidence that hyperammonemia impairs skeletal muscle strength and increased muscle fatigue and identifies a potential therapeutic target in cirrhotic patients.

Keywords: cirrhosis, force, hyperammonemia, skeletal muscle

the estimated prevalence of cirrhosis in the United States in 2010 was 0.27%, which corresponds to 633,000 adults (33). Muscle strength in cirrhotic patients is not only reduced but is also an independent predictor of adverse clinical outcomes, including decreased survival rates (2, 4, 10, 22). In addition, subjective fatigue is reported (23), but there are no published data on objective measures of skeletal muscle fatigability in cirrhosis. However, reduced muscle strength contributes to reduced exercise tolerance and activities of daily living, which ultimately impairs quality of life (6, 21). Despite recognition of the high clinical significance of impaired skeletal muscle contractile function, there are no effective therapies because the specific mechanisms are poorly understood (3, 21, 28).

We have previously shown that hyperammonemia, due to hepatocellular dysfunction and portosystemic shunting in liver disease (27), is a mediator of the liver-muscle axis and is responsible for sarcopenia in cirrhosis with portosystemic shunting (10). Hyperammonemia activates skeletal muscle proteolysis by autophagy and upregulates myostatin expression that impairs protein synthesis (10, 31) with consequent sarcopenia. Thus, sarcopenia is, at least, partially responsible for the impaired grip strength observed in the hyperammonemic portacaval anastamosis (PCA) rat (10, 11), a model that allows us to dissect the consequences of portosystemic shunting from the necroinflammatory responses of cirrhosis (9). Skeletal muscle excitation/contractile dysfunction, in addition to sarcopenia, may also be a determinant of muscle strength, but there are no studies that have systematically examined contractile function in cirrhosis. Previous reports have, however, shown that ammonia depolarizes the membrane potential resulting in reduced excitability of muscle fibers in response to electrical stimulation (18, 36) and reduced contractility of rat diaphragm muscle (35).

The purpose of this investigation was to determine whether hyperammonemia in cirrhosis was a mediator of the impaired skeletal muscle contractile function, independent of reduced muscle mass. We used a comprehensive array of models, including human cirrhosis, the hyperammonemic portacaval anastomosis rat, and ex vivo muscle preparation. Specifically, we measured maximum grip strength and contractile strength after repetitive submaximal contraction in patients with cirrhosis and controls. We then examined if grip strength normalized to skeletal muscle mass (quantified as lean body mass) (12) is reduced in hyperammonemic PCA rats. Others have reported that ammonia impairs skeletal muscle contraction (18, 35). In the present study, we quantified force production, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation in ex vivo skeletal muscle preparation. We hypothesized that maximum grip strength will be lower and muscle fatigue greater in human cirrhosis compared with controls. We also hypothesized that grip strength normalized to muscle mass will be lower in the PCA rat and inversely related to muscle and blood ammonia concentrations.

METHODS

Human studies.

Patients with cirrhosis, as well as age- and gender-matched healthy controls were recruited for this investigation. Cirrhosis was diagnosed by liver biopsy and/or clinical, laboratory, and imaging criteria. The clinical and demographic details of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Maximum grip strength was measured in the nondominant hand using a Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer (Jamar Plus+; Sammons Preston, Rolyon, Bolingbrook, IL). After the initial maximum grip, subjects continued with hand grips at 40% of maximum grip every 2 s for 3 min, and the postrepetitive contraction final maximum grip strength was measured. The initial and final maximum grip strength and the difference between the two readings were quantified. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cleveland Clinic, and written informed consent was obtained in all subjects.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with cirrhosis and control subjects

| Characteristic | Control | Cirrhosis |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 16 | 16 |

| Age, yr | 59.9 ± 10.5 | 63.9 ± 6.0 |

| Gender (M:F) | 11:5 | 11:5 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| NASH | 5 | |

| Alcohol | 7 | |

| Viral hepatitis | 2 | |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 2 | |

| Child-Pugh score | 8.3 ± 1.5 | |

| MELD score | 8.8 ± 1.9 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.4 ± 3.9 | 27.6 ± 3.6*** |

| Initial grip strength, kg | 35.6 ± 11.4 | 21.6 ± 9.2*** |

| Final grip strength, kg | 31.2 ± 9.2 | 17.7 ± 9.5*** |

| Unable to complete study | 0 | 4 (25%)*** |

| Final grip strength (%initial) | 89.8 ± 10.3 | 77.7 ± 19.5 |

All values are expressed as means ± SD.

NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

P < 0.001.

Animals.

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Cleveland Clinic and the Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center and conformed to animal care guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (∼9 wk old; 250–260 g) with an end to side PCA or sham surgery (Charles River, Wilmington, DE) were housed individually in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. The care of these animals has been described previously (9, 11). In brief, pair feeding was done by providing the sham-operated control rats with the same quantity of standard rat chow (Harland Teklad rodent chow no. 8604; protein 24.5%, fat 4.4%, and 3.93 kcal/g), as had been ingested by a paired PCA rat fed ad libitum. Pair feeding eliminated the effect of differences in food intake on measures of body composition and muscle function. Food and water intake were measured daily, and total body mass and lean body mass were measured weekly (Table 2). Lean body mass was obtained weekly using the TOBEC body analyzer for small animals (SA-3000) fitted with the 114 × 318 mm measuring chamber (SA-3114) (EC Systems, Springfield IL).

Table 2.

Characteristics of PCA and sham rats

| Characteristic | Sham | PCA |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 5 | 5 |

| Initial body weight, g | 256 ± 5.3 | 254.6 ± 5.1 |

| Initial lean body mass, g | 222.2 ± 7.0 | 219.2 ± 6.1 |

| Final body weight, g | 387.0 ± 28.3 | 282.4 ± 21.1*** |

| Final lean body mass, g | 323.6 ± 26.1 | 256.2 ± 23.11*** |

| Total food intake, g | 567.4 ± 18.1 | 575.1 ± 18.3 |

| Average daily food intake, g | 20.4 ± 0.7 | 20.3 ± 0.7 |

| Food efficiency | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.046 ± 0.045*** |

| Total water intake, ml | 725.6 ± 10.1 | 722.8 ± 8.2 |

| Daily water intake, ml | 25.8 ± 0.29 | 25.9 ± 0.36 |

All values are expressed as means ± SD.

PCA, portacaval anastomosis.

P < 0.001.

Grip strength.

Grip strength was measured in the PCA and sham-operated control rats at 4 wk after the surgery using a computerized rat grip strength meter (model no. 1067CSX; Columbus Instruments, Columbus OH), as described previously (11). In brief, a supported T-bar was attached to the load cell with a sampling rate of 1,000 Hz. After animals were acclimatized to handling the T-bar with their front limbs, the rat was then pulled away from the bar with gradually increasing force by holding the base of the tail until the rat released the bar. The maximal force, the force just prior to release of the T bar, was recorded. Each animal was tested three times in succession and then repeated twice after a 30-min rest period. All measurements were performed by a single operator.

Euthanasia and harvesting.

Following grip strength measurements, animals were euthanized; aortic blood samples were drawn into EDTA-coated vials, plasma separated, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C; gastrocnemius muscle and other organs were rapidly harvested, blotted dry of blood, weighed, and flash frozen for further assays. A part of the muscle was collected in OCT compound, frozen in isopentane chilled in liquid nitrogen. Ten-micrometer cryosections were stained with ATPase at pH 10.5 (type II fibers stain dark, type 1 fibers stain light), and fiber size and typing were done using the ImageJ program (34). Ammonia concentrations were measured in plasma and muscle, as described earlier (30). In brief, skeletal muscle protein content was quantified by the bicinchoninic acid method, and muscle ammonia concentrations were normalized to protein content. Plasma ammonia was quantified in deproteinized samples using a commercially available ammonia assay kit (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All assays were done in triplicate, and the data were expressed as means ± SD.

Ex vivo rat soleus contractile function.

A separate group of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 8, age 12 wk, weight 356 ± 35 g) were matched in age and weight to the sham-operated rats at the time of euthanasia (Table 2). Rats were well anesthetized using a rodent anesthetic cocktail mixture (initial dose, ketamine 21–30 mg/kg, xylazine 4.3–6.0 mg/kg, and acepromazine 0.7–1.0 mg/kg, with supplemental smaller doses given as needed to produce and maintain a deep level of anesthesia). The soleus muscles were removed from both legs with intact tendons and placed in oxygenated physiological solution and subsequently mounted vertically in separate double-jacketed tissue baths with one end attached to an isometric force transducer (Kent Scientific/Radnotti Glass Technology, Monrovia, CA). The composition (in mM) of the physiological solution was as follows: 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 1 NaH2PO4, 15 NaHCO3, and 11 glucose, with the pH adjusted to 7.35–7.45 at 37°C while being aerated with 95% O2-5%CO2. Temperature of the medium was maintained at 37°C throughout the study period. Muscle was stimulated by placement of platinum electrodes (Radnotti Glass Technology, Monrovia, CA) directly on the muscle parallel to the longitudinal axis. Optimal length for each muscle, defined as the muscle length associated with maximum twitch force, was determined by delivering a series of single supramaximal voltages with a pulse width of 1 ms. Muscles were lengthened between subsequent stimulations until the twitch force was maximized. The muscles then remained at an optimal length for the duration of the contractile study.

Following equilibration, twitches were evoked every minute for a period of 5 min to determine baseline force and confirm contractile stability of the muscle. The right-sided muscle served as the test group, and the left-sided muscle from the same animal served as a control. After this 5-min baseline period, ammonium acetate in Krebs buffer solution was added to the bath of the right-sided muscle to a final concentration of 10 mM. An equal volume of Krebs solution alone was added to the bath of the left-sided control muscle. We have previously shown in vitro in C2C12 myotubes that 10 mM ammonium acetate in the medium results in intracellular ammonia concentrations that are similar to that in the skeletal muscle of patients with cirrhosis (30). Consistently, incubation of skeletal muscle in Krebs solution with 10 mM ammonium acetate resulted in muscle ammonia concentration of 5.01 ± 0.65 mM/g protein, which is similar to that in human cirrhotic skeletal muscle of 4.98 ± 0.41 mM/g protein (30). Following addition of ammonium acetate or control solution, twitch stimulation continued once every minute for 20 min.

Following this initial twitch protocol the muscles were then subjected to a series of tetanic contractions by stimulating the muscle for 300 ms at stimulation frequencies of 20, 35, 50, 65, 80, 95, and 110 Hz to develop a force frequency relation. A 1-min rest period was provided between each contraction. Following all contractile protocols, the length and mass of each muscle were recorded after this study, and the ammonia concentration in the muscle tissue was quantified as described earlier (30).

Force records were collected online with a PowerLab 8/35 data acquisition system and were analyzed using the associated LabChart software (AdInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). For all twitch and tetanic contractions, maximal force, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation were determined. Specifically, the rate of force development was calculated as the rate in which force increased from 10% to 90% of maximal force. Likewise, the rate of relaxation was the rate in which force decreased from 90% to 10% of maximal force following stimulation. In addition, twitch force following exposure to hyperammonemia was normalized to the average twitch force during the 5-min baseline period. Force-frequency relationships with and without the drug were determined by measuring peak force across all stimulation frequencies (20–110 Hz). Because muscle mass and initial force generated on the two sides from the same animal were similar and each treated muscle was matched to the control muscle from the contralateral limb of the same animal, force was not normalized to muscle mass or cross-sectional area.

Immunoprecipitation for nitration of myosin heavy chain.

To determine whether the major contractile protein, myosin heavy chain (38), is posttranslationally modified by ammonia, total protein was extracted from C2C12 murine myotubes grown to differentiation for 48 h, as previously described (30). Cells were then treated with 10 mM ammonium acetate for 24 h. We have previously reported that this concentration of ammonium acetate results in a cellular ammonia level similar to that in the skeletal muscle of human cirrhotic patients (30) and in the PCA rat (present study). For immunoprecipitation studies, 20 μl of protein A/G agarose beads were added to 500 μl of protein lysate (200 μg protein), and incubated in a shaker for 1 h at 4°C. This was followed by centrifugation at 14,000 g at 4°C for 5 min. The bead pellet was discarded, and to the supernatant, 2 μg of affinity-purified polyclonal antimyosin heavy-chain antibody (cat. no. 05–716; Millipore, Billerica, MA) (1:200) was added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C by rotating in an orbital shaker. Protein A/G agarose beads were then added, and the lysate-bead mixture was incubated at 4°C under rotary agitation overnight. The lysate bead mixture was then centrifuged, supernatant was removed, and beads were washed three times in lysis buffer. About 50 μl of 2× loading buffer was added to the washed bead, and was then boiled for 5 min to denature the protein and separate it from the protein-A/G beads. Following centrifugation, the supernatant containing the immunoprecipitated myosin heavy chain was run on an 8% Tris-glycine gel, electrotransferred to PVDF membrane, incubated with anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (cat. no. 05–233; Millipore, Billerica, MA) (1:10,000) at 4°C overnight and then treated with secondary antibody and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence plus solution, and blots were developed. The membrane was also probed for myosin heavy chain to ensure equal loading of protein, and nonspecific immunoglobulin was used as a negative control.

Data analysis.

All data were expressed as means ± SD unless specified. χ2-test was used to compare qualitatively, and the Student's t-test for independent groups was used to compare quantitative variables. Normalized grip strength was correlated with blood and skeletal muscle ammonia concentrations across both control and PCA rats using the Pearson's correlation coefficient. To determine whether hyperammonemia causes muscle dysfunction, twitch force, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation were compared between control and ammonia acetate-treated muscles with mixed-design ANOVAs followed by post hoc comparisons between groups. Benjamini-Hochberg-α correction was used to minimize the chance of a type 1 error. In regard to the force-frequency relationship, two-way mixed-design ANOVAs were performed to determine whether ammonia acetate influenced muscular force, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation across a range of stimulation frequencies. The α-level for all comparisons was set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Human studies.

Contractile strength measurements are shown in Table 1. Initial maximum grip strength and postrepetitive contraction grip strength were both significantly lower (P < 0.001) in patients with cirrhosis than in controls. Additionally, 4 out of 16 (25%) patients with cirrhosis could not complete the repetitive contraction component due to extreme muscle fatigue in the hand, while all control subjects completed the study. All four subjects who could not complete the study had a child's score ≥7. The difference between the initial maximum and post-repetitive contraction grip strength (expressed as a percentage of the initial grip strength) was also significantly greater in patients with cirrhosis than controls. Because the number of subjects was small, it was not possible to determine whether contractile dysfunction was related to the etiology of cirrhosis.

PCA rat grip strength and ammonia concentrations.

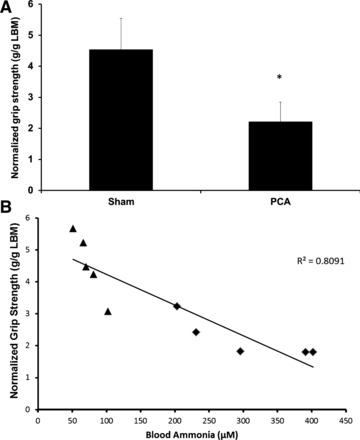

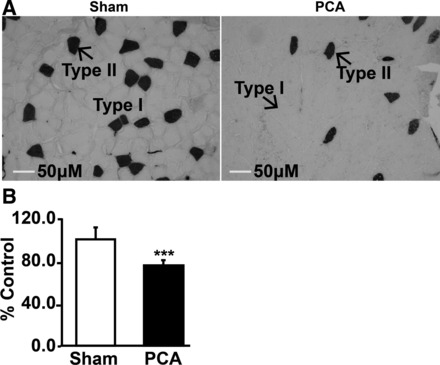

Plasma and muscle ammonia concentrations in the PCA were significantly higher than in sham-operated control rats (Table 2). There was a strong correlation between plasma and skeletal muscle ammonia concentrations (r2 = 0.88; P < 0.01 in the PCA, r2 = 0.64; P < 0.05 sham; and r2 = 0.89; P < 0.01 when both groups were combined). Grip strength normalized to lean body mass was significantly reduced in the PCA rats (2.22 ± 0.62 g/g lean body mass) compared with control rats (4.54 ± 0.99 g/g lean body mass, P = 0.001) (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, there was a strong inverse correlation (r2 = 0.81, P = 0.002) between blood ammonia concentration and grip strength when the PCA and control rats were pooled together (Fig. 1B). Similarly, muscle ammonia concentrations were inversely correlated with grip strength (r2 = 0.82; P < 0.01). Cryosections of gastrocnemius muscle from the PCA rat showed a reduction in fiber diameter compared with sham-operated control rats. There was also loss of type II fibers with no inflammatory cell infiltration or myonecrosis (Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 1.

Grip strength for portacaval anastomosis (PCA) and sham-treated rats. A: grip strength (means ± SD) normalized to lean body mass (n = 6). *Significant difference between the two conditions (P = 0.001). B: correlation between normalized grip strength and blood ammonia concentration across both control (triangles) and PCA (diamond) rats.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemistry of cryosections of gastrocnemius muscle of sham-operated control and hyperammonemic PCA rat. A: gastrocnemius muscle stained with ATPase at pH 10.4. Dark-stained type II fibers and light-stained type I fibers showed loss of type II fibers and reduction in diameter of both fiber types. B: quantification of fiber diameter in gastrocnemius muscle of the PCA rats expressed as a percentage of that from sham-operated control rats. Data from at least 120 fibers (means ± SD). ***P < 0.001.

Ammonium acetate-treated isolated muscle.

The mass of the soleus muscles was not different between control (0.124 ± 0.033 g) and ammonium acetate-treated (0.121 ± 0.037 g) conditions (P = 0.67). Furthermore, the twitch force during the initial 5-min baseline period was also not different between the two groups (control: 15.5 ± 6.4 g, hyperammonemia: 15.3 ± 6.2 g; P = 0.906). Post hoc analysis of the muscle tissue revealed that the ammonia concentration in control muscles was 0.39 ± 0.08 mM/g protein and 4.7 ± 0.7 mM/g protein in the ammonia-treated muscles (P < 0.001).

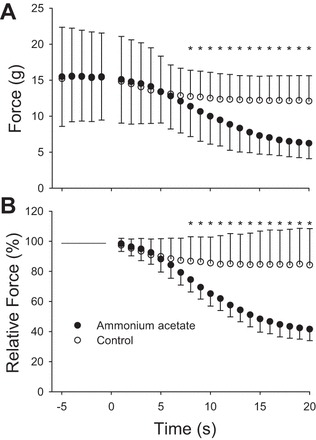

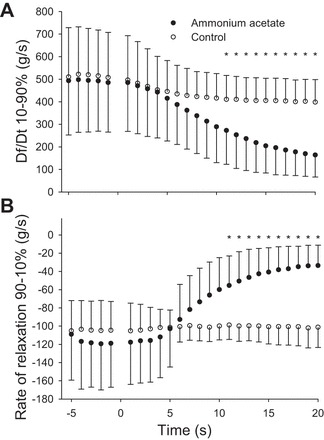

Within 8 min of exposure to hyperammonemia, muscles generated significantly less twitch force than their control counterparts (P = 0.02). By the end of the 20-min protocol, muscles treated with ammonium acetate were producing 41.5 ± 7.6% of baseline force, whereas the control pairs were producing 84.2 ± 24.2% of baseline (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3, A and B). The reduction in muscle twitch force stabilized by 20 min. In addition, within 11 min, the muscles treated with ammonium acetate had a reduced rate of force development (P = 0.044) and rate of relaxation (P = 0.037) compared with control muscles (Fig. 4, A and B). During the subsequent 9 min, the rate of force development and rate of relaxation continued to decrease, and at 20 min of exposure to hyperammonemia, the rates were 40 ± 24% and 34 ± 23% of that in the control muscles, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Influence of ammonium acetate on twitch force. Time −5 through 0 represent the 5-min baseline period. At time 0, either ammonia acetate or Krebs solution was added to the muscle bath. A: illustration of the absolute twitch force. B: illustration of the relative change from baseline for the two conditions. Significant difference (*P < 0.05) in force between the muscle treated with ammonia acetate and those treated with normal Krebs solution. Values are presented as means ± SD.

Fig. 4.

Influence of ammonium acetate on rate of force development (A) and rate of relaxation (B). Time −5 through 0 represent the 5 min baseline period. At time 0, either ammonia acetate or Krebs solution was added to the muscle bath. Significant difference (*P < 0.05) in force between the muscle treated with ammonia acetate and those treated with normal Krebs solution. Values are presented as means ± SD.

Force-frequency relationship.

The reduction in force, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation observed with the single-twitch contractions was also observed when the muscles were stimulated with pulse trains across a range of stimulation frequencies (20–110 Hz). Specifically, across all stimulation frequencies, the tetanic force was reduced between 55% and 64% in the muscles treated with ammonium acetate compared with controls (P < 0.008 for all comparisons) (Fig. 5A). In addition, the rate of force development was depressed between 56% and 60%, and the rate of relaxation was depressed between 69% and 71% across all stimulation frequencies in the muscles treated with ammonia acetate (P ≤ 0.009 for all comparisons; Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 5.

Influence of ammonium acetate on tetanic force (A), rate of force development (B), and rate of relaxation (C) across a range of stimulation frequencies. Across all stimulation frequencies, statistical significance was achieved for all comparisons between muscles treated with Krebs solution and those treated with ammonia acetate. Significant difference (*P < 0.05) in force between the muscle treated with ammonia acetate and those treated with normal Krebs solution. Values represent means ± SD.

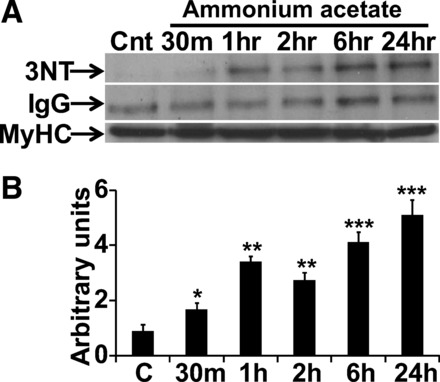

Nitration of myosin heavy chain.

Immunoprecipitation studies showed nitration of myosin heavy chain during hyperammonemia compared with controls cells, suggesting that posttranslational modifications of proteins may contribute to impaired contractile function (Fig. 6, A and B).

Fig. 6.

Representative immunoblots and densitometry of nitrated myosin heavy chain (MyHC). A: myosin heavy chain was immunoprecipitated from C2C12 myotubes treated with 10 mM ammonium acetate and control cells for different time points (0–24 h). Immunoprecipitates were then probed with antinitrotyrosine antibody. IgG was used as a negative control and myosin heavy chain was probed to demonstrate equal loading. B: densitometry from three independent experiments showing nitration of myosin heavy chain in ammonia-treated myotubes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. untreated control (C) myotubes.

DISCUSSION

The present studies show that patients with cirrhosis have lower grip strength and, importantly, more rapid muscle fatigue compared with healthy controls. The hyperammonemic PCA rats have lower grip strength when normalized to lean body mass compared with control rats and grip strength correlated inversely with the blood and skeletal muscle ammonia concentrations. Consistently, our ex vivo experiments revealed that skeletal muscle force production, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation following single pulses and pulse trains across a range of stimulation frequencies were lower during hyperammonemia. Finally, hyperammonemia resulted in nitration of myosin heavy chain, a major contractile protein in the skeletal muscle. Together, these data indicate that hyperammonemia is a mediator of reduced muscle contractile function independent of reduced muscle mass and provides a potential therapeutic target to reverse muscle weakness in cirrhosis.

Our human data, which indicates patients with cirrhosis have significantly lower grip strength than controls, was consistent with previous reports (2, 4). This is, however, the first study that evaluated skeletal muscle response to repetitive contraction and fatigue. Nearly one-third of patients with cirrhosis could not perform the 3-min repetitive submaximal contraction, while all of the controls were able to complete the study. Interestingly, the maximum grip strength following 3 min of submaximum repetitive contractions was reduced in both groups, the reduction was significantly greater in cirrhotic patients. One of the mechanisms of muscle fatigue in response to contraction has been suggested to be due to increased muscle ammoniagenesis. Because we have previously shown that muscle ammonia concentration in the skeletal muscle of cirrhotic patients is significantly higher than in controls (30), our current PCA rat and ex vivo studies indicate that higher muscle hyperammonemia was a mechanism of the reduced strength and increased fatigue observed in those with cirrhosis.

Models used.

We have used two approaches to identify that ammonia is responsible for specific contractile dysfunction associated with liver disease, in vivo studies in the PCA rat, and ex vivo studies in isolated skeletal muscle. Our in vivo PCA rat is an established model of hyperammonemia of portosystemic shunting in liver disease that reproduces the clinical, biochemical, hormonal, and metabolic perturbations of cirrhosis that are due to the vascular consequences of cirrhosis. Even though cirrhosis does not develop in the PCA rat, the major strength of this model is that it allows us to dissect the vascular consequences from the necroinflammatory effects of cirrhosis. Rodent models of cirrhosis include the carbon tetrachloride-induced fibrosis, which is not an appropriate model because carbon tetrachloride is directly toxic to the skeletal muscle (32), and the bile duct ligation, which has steatorrhea that makes it difficult to separate the muscle atrophy due to malabsorption from that secondary to cirrhosis (15). Furthermore, since the perturbations in the PCA rat are established at surgery (11, 26), a time course can be defined, and on the basis of our previous studies characterizing this model (9, 11–14), the variability within the disease group is much less than would be when there is ongoing toxin administration or continued, but variable, steatorrhea. We have previously reported that the grip strength and skeletal muscle mass are lower in the PCA rat (11). The present studies show that lower grip strength in the PCA compared with sham-operated control rats is independent of the lower muscle mass. Finally, our studies in patients with cirrhosis allow direct translation of our animal and ex vivo studies. Our novel data showed that grip strength normalized to lean body mass is decreased in the hyperammonemic PCA compared with that in control rats. This is also the first report of in vivo studies that show grip strength is highly correlated with plasma and skeletal muscle ammonia concentrations. Our ex vivo preparation was optimized so that muscle concentrations of ammonia were similar to that seen in patients with cirrhosis (30) and the PCA rat, which allowed us to examine the characteristics of skeletal muscle contractile dysfunction independent of reduced muscle mass. Our data show that maximal force, rate of force development, and rate of relaxation are all reduced due to the influx of ammonia into the muscle. This complementary approach has, thus, allowed us to identify hyperammonemia as the specific mediator of contractile dysfunction in cirrhosis and potentially other hyperammonemic disorders.

Skeletal muscle uptake and effects of ammonia in liver disease.

In patients with acute and chronic liver disease, the skeletal muscle contributes to ammonia disposal by increased uptake and metabolism to glutamate and glutamine that are then exported out of the muscle (7, 16, 19, 24). We and others have reported skeletal muscle hyperammonemia impairs skeletal muscle protein synthesis and increases autophagy that contributes to sarcopenia in cirrhosis (20, 30, 31). Consistent with previous data on increased uptake of ammonia by the skeletal muscle, muscle ammonia concentrations in the PCA rat was significantly higher than in sham-operated controls. Our data also show that lower skeletal muscle mass in the PCA rat was accompanied by reduced fiber diameter, but there was no evidence of myonecrosis or inflammatory infiltrate, indicating that the effects are due to loss of protein content rather than a direct injury to the muscle. Furthermore, the loss of type IIB fibers is similar to that reported in other models of cirrhosis (17). The present studies provide compelling novel data that, hyperammonemia alters skeletal muscle contractile function and increases fatigue independent of the loss of muscle mass. Our data are also important because, even though ammonia has been previously suggested to cause fatigue following exercise (5, 37), it is not known whether this is responsible for the muscle dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis. Cerebral disposal of ammonia may be adequate during limited ammonia generation during intense exercise (8), but in hepatic disease, skeletal muscle becomes a major alternate organ for ammonia disposal (7). Our ex vivo studies show that increased muscle uptake of ammonia directly impairs contractile response, the major nonmetabolic skeletal muscle mechanical function.

Contractile dysfunction during hyperammonemia.

Previous reports have suggested that physiological concentrations of ammonia do not adversely affect diaphragm contractility (35). Our data are, however, consistent with this report that ammonia impairs in vitro diaphragm contractile function only at concentrations above 5 mM in the medium, which are not in the physiological range of plasma. A true measure of the effects of ammonia is, however, the muscle tissue concentration. In cirrhosis, muscle uptake and concentrations are significantly higher than that following exercise, and our studies using the biologically appropriate muscle concentrations provide direct evidence that contractile dysfunction ex vivo and lower in vivo grip strength in portosystemic shunting in liver disease are mediated by hyperammonemia. This interpretation is consistent with a previous report of decrease in diaphragm contractility following exposure to 5, 10, and 14 mM ammonium chloride when both the rate of force development and rate of relaxation were impaired following exposure to ammonium acetate (35). To demonstrate that ammonia results in impaired contractile function independent of loss of muscle mass, grip strength was normalized to lean body mass and gastrocnemius muscle mass. We have previously shown that lean body mass was a noninvasive measure of skeletal muscle mass in rats (12) and by normalizing the muscle strength to lean body mass, we noted that hyperammonemia resulted in lower muscle contraction independent of muscle loss in vivo in the PCA rat.

Electrophysiology of ammonia induced muscle dysfunction.

A potential mechanism for the hyperammonemia-induced decrease in muscle contractility is a reduction in membrane potential (1, 18). Heald (18) reported that ammonium ions can either potentiate or depress contractile function depending on their concentration. Specifically, frog sartorius muscle fibers were potentiated when 30 mM NH4Cl replaced NaCl in the bathing solution but was depressed when much higher concentrations of ammonium chloride (90 and 120 mM) replaced NaCl. The reduction in force at higher concentrations was due to depolarization of the resting membrane potential and subsequent loss of excitable fibers. In addition, on the basis of the fact that outward membrane currents could produce contractions and that hyperammonemia did not block caffeine-induced contractures, Heald concluded that the surface membrane, not the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) or contractile apparatus, is the major site of interference by ammonium. It is important to note that the concentrations of ammonium chloride used by Heald were much greater than what has been reported in human cirrhosis (30). However, Stephenson and Stephenson (36) reported that the magnitude of twitch force did not differ between control fibers and fibers exposed to 2–10 mM NH4OH, yet the twitch duration was reduced by 11–25%. They concluded that changes in the twitch duration may reflect change in voltage sensor activation, changes in the SR induced calcium movements or changes to calcium sensitivity of actin. Two major differences in the muscle preparation between our investigation and that of Heald's and Stephenson's is our use of whole muscle, not muscle fibers, and we simply added ammonium acetate to the bath solution rather than replace sodium with the ammonium ion.

Potential mechanisms of ammonia induced contractile dysfunction.

Muscle contraction is an energy-intense process, and impaired mitochondrial function and ATP content have been reported in the skeletal muscle of patients with cirrhosis. Ammonia also can potentially cause posttranslational modifications, including protein nitration and oxidative stress-induced carbonylation of contractile proteins with impaired actomyosin interactions. We noted nitration of major structural protein and myosin heavy chain in myotubes in response to hyperammonemia. Because nitration of proteins has been reported to impair function, ammonia-mediated nitration is a potential molecular mechanism of impaired contractile function (25). Future studies will allow dissection of the specific molecular and biochemical mechanisms of ammonia-induced impaired mechanical function of the muscle.

Strengths and limitations of the study.

The major strength of these studies is the identification of ammonia as a mediator of abnormal muscle contractile function in cirrhosis with portosystemic shunting, which provides the rationale for using ammonia-lowering therapies to improve muscle strength. This is reiterated by a previous report suggesting that following liver transplantation, when hepatic ammonia metabolism normalizes, grip strength normalizes, even before muscle mass improves (29). Because ammonia-lowering therapies are routinely used in treating patients with cirrhosis and encephalopathy, our studies have the potential for rapid clinical translation. A potential limitation is that the exact molecular mechanism by which ammonia impairs contractile function and accelerates fatigue is not known. However, our novel data lay the foundation for studies to determine the mechanisms(s) of ammonia-induced impaired muscle contractile and fatigue responses in cirrhosis and potentially other chronic diseases with hyperammonemia. Even though cirrhosis is a complex disease with multiple metabolic perturbations, ammonia is the best established mediator to date of the liver-muscle axis. Other mechanisms may also contribute to impaired contractile function in liver disease, but our studies show that hyperammonemia does contribute to contractile dysfunction.

Key findings of the study.

These data provide evidence for ammonia as a mediator at least partially responsible for the impaired contractile function of the skeletal muscle in cirrhotic patients. A number of potential mechanisms can contribute to the impaired muscle contraction and relaxation, and include ammonia-induced impairment in mitochondrial function and ATP generation, posttranslational modifications of critical contractile proteins, and altered membrane potential. Our studies lay the foundation for mechanistic studies to reverse impaired muscle contraction and relaxation during hyperammonemia. These data are of broad interest because hyperammonemia has been reported in other chronic disorders, including advance heart failure and chronic obstructive lung disease, both of which have sarcopenia and impaired contractile function.

GRANTS

This study was funded through Career Development Award (CDA2 E7560W) to J. McDaniel. S. Dasarathy was supported, in part, by NIDDK RO1 DK-83411, R21 AA-022742.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.M., M.M., E.v.L., and S.D. conception and design of research; J.M., E.A.H., M.M., A.R., R.P., E.v.L., and S.D. performed experiments; J.M., G.D., E.A.H., A.R., R.P., and S.D. analyzed data; J.M., G.D., and S.D. interpreted results of experiments; J.M. and S.D. prepared figures; J.M. and S.D. drafted manuscript; J.M., M.M., E.v.L., and S.D. edited and revised manuscript; J.M., G.D., M.M., E.v.L., and S.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aickin CC, Thomas RC. An investigation of the ionic mechanism of intracellular pH regulation in mouse soleus muscle fibres. J Physiol 273: 295–316, 1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvares-da-Silva MR, Reverbel da Silviera T. Comparison between handgrip strength, subjective global assessment, and prognostic nutritional index in assessing malnutrition and predicting clinical outcome in cirrhotic outpatients. Nutrition 21: 113–117, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen H, Aagaard NK, Jakobsen J, Dorup I, Vilstrup H. Lower muscle endurance in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Int J Rehab Res 35: 20–25, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen H, Borre M, Jakobsen J, Andersen PH, Vilstrup H. Decreased muscle strength in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis in relation to nutritional status, alcohol abstinence, liver function, and neuropathy. Hepatology 27: 1200–1206, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banister EW, Cameron BJ. Exercise-induced hyperammonemia: peripheral and central effects. Int J Sports Med 11 Suppl 2: S129–S142, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biagini MR, Tozzi A, Grippo A, Galli A, Milani S, Amantini A. Muscle fatigue in women with primary biliary cirrhosis: Spectral analysis of surface electromyography. World J Gastroenterol 12: 5186–5190, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatauret N, Desjardins P, Zwingmann C, Rose C, Rao KV, Butterworth RF. Direct molecular and spectroscopic evidence for increased ammonia removal capacity of skeletal muscle in acute liver failure. J Hepatol 44: 1083–1088, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalsgaard MK, Ott P, Dela F, Juul A, Pedersen BK, Warberg J, Fahrenkrug J, Secher NH. The CSF and arterial to internal jugular venous hormonal differences during exercise in humans. Exp Physiol 89: 271–277, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasarathy S, Dodig M, Muc SM, Kalhan SC, McCullough AJ. Skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with an increased expression of myostatin and impaired satellite cell function in the portacaval anastamosis rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G1124–G1130, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Muc S, Schneyer A, Bennett CD, Dodig M, Kalhan SC. Sarcopenia associated with portosystemic shunting is reversed by follistatin. J Hepatol 54: 915–921, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasarathy S, Muc S, Hisamuddin K, Edmison JM, Dodig M, McCullough AJ, Kalhan SC. Altered expression of genes regulating skeletal muscle mass in the portacaval anastomosis rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1105–G1113, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasarathy S, Muc S, Runkana A, Mullen KD, Kaminsky-Russ K, McCullough AJ. Alteration in body composition in the portacaval anastamosis rat is mediated by increased expression of myostatin. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G731–G738, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dasarathy S, Mullen KD, Conjeevaram HS, Kaminsky-Russ K, Wills LA, McCullough AJ. Preservation of portal pressure improves growth and metabolic profile in the male portacaval-shunted rat. Dig Dis Sci 47: 1936–1942, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasarathy S, Mullen KD, Dodig M, Donofrio B, McCullough AJ. Inhibition of aromatase improves nutritional status following portacaval anastomosis in male rats. J Hepatol 45: 214–220, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vriese SR, Savelii JL, Poisson JP, Narce M, Kerremans I, Lefebvre R, Dhooge WS, De Greyt W, Christophe AB. Fat absorption and metabolism in bile duct ligated rats. Ann Nutrit Metab 45: 209–216, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganda OP, Ruderman NB. Muscle nitrogen metabolism in chronic hepatic insufficiency. Metabolism 25: 427–435, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gayan-Ramirez G, van de Casteele M, Rollier H, Fevery J, Vanderhoydonc F, Verhoeven G, Decramer M. Biliary cirrhosis induces type IIx/b fiber atrophy in rat diaphragm and skeletal muscle, and decreases IGF-I mRNA in the liver but not in muscle. J Hepatol 29: 241–249, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heald DE. Influence of ammonium ions on mechanical and electrophysiological responses of skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol 229: 1174–1179, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holecek M, Kandar R, Sispera L, Kovarik M. Acute hyperammonemia activates branched-chain amino acid catabolism and decreases their extracellular concentrations: different sensitivity of red and white muscle. Amino Acids 40: 575–584, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holecek M, Sprongl L, Tichy M. Effect of hyperammonemia on leucine and protein metabolism in rats. Metabolism 49: 1330–1334, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollingsworth KG, Newton JL, Taylor R, McDonald C, Palmer JM, Blamire AM, Jones DE. Pilot study of peripheral muscle function in primary biliary cirrhosis: potential implications for fatigue pathogenesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 6: 1041–1048, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones JC, Coombes JS, Macdonald GA. Exercise capacity and muscle strength in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Transpl 18: 146–151, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalaitzakis E, Josefsson A, Castedal M, Henfridsson P, Bengtsson M, Hugosson I, Andersson B, Bjornsson E. Factors related to fatigue in patients with cirrhosis before and after liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 174–181, 181 e171, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockwood AH, McDonald JM, Reiman RE, Gelbard AS, Laughlin JS, Duffy TE, Plum F. The dynamics of ammonia metabolism in man. Effects of liver disease and hyperammonemia. J Clin Invest 63: 449–460, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mani AR, Ippolito S, Ollosson R, Moore KP. Nitration of cardiac proteins is associated with abnormal cardiac chronotropic responses in rats with biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 43: 847–856, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mans AM, DeJoseph MR, Davis DW, Vina JR, Hawkins RA. Early establishment of cerebral dysfunction after portacaval shunting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 259: E104–E110, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olde Damink SW, Jalan R, Dejong CH. Interorgan ammonia trafficking in liver disease. Metab Brain Dis 24: 169–181, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panzak G, Tarter R, Murali S, Switala J, Lu S, Maher B, Van Thiel DH. Isometric muscle strength in alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver-transplantation candidates. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 24: 499–512, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plank LD, Metzger DJ, McCall JL, Barclay KL, Gane EJ, Streat SJ, Munn SR, Hill GL. Sequential changes in the metabolic response to orthotopic liver transplantation during the first year after surgery. Ann Surg 234: 245–255, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu J, Thapaliya S, Runkana A, Yang Y, Tsien C, Mohan ML, Narayanan A, Eghtesad B, Mozdziak PE, McDonald C, Stark GR, Welle S, Naga Prasad SV, Dasarathy S. Hyperammonemia in cirrhosis induces transcriptional regulation of myostatin by an NF-κB-mediated mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 18,162–18,167, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu J, Tsien C, Thapalaya S, Narayanan A, Weihl CC, Ching JK, Eghtesad B, Singh K, Fu X, Dubyak G, McDonald C, Almasan A, Hazen SL, Naga Prasad SV, Dasarathy S. Hyperammonemia-mediated autophagy in skeletal muscle contributes to sarcopenia of cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303: E983–E993, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanzgiri UY, Srivatsan V, Muralidhara S, Dallas CE, Bruckner JV. Uptake, distribution, and elimination of carbon tetrachloride in rat tissues following inhalation and ingestion exposures. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 143: 120–129, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, Shoham D, Durazo R, Luke A, Volk ML. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: a population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol 49: 690–696, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671–675, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanely RA, Coast JR. Effect of ammonia on in vitro diaphragmatic contractility, fatigue and recovery. Respiration 69: 534–541, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephenson GM, Stephenson DG. Effects of ammonium ions on the depolarization-induced and direct activation of the contractile apparatus in mechanically skinned fast-twitch skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 17: 611–616, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilkinson DJ, Smeeton NJ, Watt PW. Ammonia metabolism, the brain and fatigue; revisiting the link. Progr Neurobiol 91: 200–219, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yates LD, Greaser ML. Quantitative determination of myosin and actin in rabbit skeletal muscle. J Mol Biol 168: 123–141, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]