Abstract

Background

Treatment recommendations have been developed for management of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Methods

A 30-item multiple-choice questionnaire was administered to 435 hematologists and onco-hematologists in 16 Latin American countries. Physicians self-reported their diagnostic, therapeutic, and disease management strategies.

Results

Imatinib is available as initial therapy to 92% of physicians, while 42% of physicians have access to both 2nd generation TKIs. Standard-dose imatinib is the preferred initial therapy for most patients, but 20% would manage a young patient initially with an allogeneic stem cell transplant from a sibling donor and 10% would only offer hydroxyurea to an elderly patient. Seventy-two percent of responders perform routine cytogenetic analysis for monitoring patients on therapy and 59% routinely use quantitative PCR. For patients who fail imatinib therapy, 61% would increase the dose of imatinbi before considering change to a second generation TKI, except for patients age 60 years for whom a switch to second generation TKI was the preferred choice.

Conclusions

The answers to this survey provide insight into the management of patients with CML in Latin America. Some deviations from current recommendations were identified. Understanding the treatment patterns of patients with CML in broad population studies is important to identify needs and improve patient care.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia, imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, TKIs, guidelines, CML, Latin America, survey, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Condensed Abstract

A survey of 435 physicians in 15 Latin American countries revealed that in general most follow current recommendations for the use of imatinib to treat patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). However, significant variability is evident regarding the management of CML patients, determined in great part by availability of resources.

INTRODUCTION

Imatinib is the established standard of care for initial treatment of chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)1. Although most patients have a favorable outcome, some patients are initially refractory or develop acquired resistance2. Second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) provide alternative therapeutic options for CML patients who fail imatinib. With the availability of more effective therapeutic options, adequate use of therapies and proper monitoring have become increasingly important to optimize patient outcomes. The European Leukemia Net has summarized the current understanding of the management of CML and provided recommendations to guide physicians on how to best treat and monitor their patients to help accomplish the best possible outcome for patients with CML1. These recommendations, consider the optimal management of patients under ideal circumstances that may include wide availability of all therapeutic and monitoring tools. Recent studies have analyzed how patients in Europe and the United States of America are treated3. However, other areas of the world may have different approaches affected by regional factors such as availability of drugs and tests, cultural elements, and financial considerations. The goal of this study was to ascertain how physicians throughout Latin America perceive and use the available CML therapies, and to identify strategies used to diagnose and manage the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A questionnaire was developed to assess Latin American physicians’ self-reported CML diagnostic, treatment and monitoring strategies. Hematologists and onco-hematologists were recruited from a large database and invited, either by phone or e-mail, to participate in the study. The anonymous and confidential questionnaire was created by the Latin American Leukemia Net (LALNET), and applied by an independent agency through internet or telephone interviews. Prior to beginning, participants were informed the questionnaire would take 20–25 minutes to complete. The 30-item multiple-choice questionnaire is shown in Table 1. Prior to beginning the questionnaire, physicians were surveyed to determine their study eligibility. Participants were considered eligible if they had prescribed imatinib for any condition, and had treated ≥5 CML patients outside the context of a clinical trial in the prior 2 years, and were treating at least 2 CML patients at the time of the survey.

Table 1.

Questions and answers in the internet or phone interviews

| 1 |

When a patient of yours receives a preliminary diagnosis of CML, where do you typically obtain confirmatory testing by cytogenetics and/or FISH? |

At your institution/hospital; Nearby institution/hospital lab in your country; Institution/hospital in another country; Commercial laboratory; Other |

| 2 |

When a new patient of yours receives a preliminary diagnosis of CML, where do you typically obtain confirmatory testing by qRT-PCR and / or BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation ? |

At your institution/hospital; Nearby institution/hospital lab in your country; Institution/hospital in another country; Commercial laboratory; Other |

| 3 |

When evaluating a patient with a white cell count (eg. 65,000) and a morphologic picture compatible with CML, which of the following initial diagnostic tests would you typically perform? Please choose all that apply. |

Bone marrow aspiration; Biopsy; Cytogenetics; FISH; Quantitative PCR; BCR-ABL mutation analysis; Other |

| 4 |

In addition to peripheral blood counts, which of the following do you routinely use in monitoring response to Imatinib therapy? Please choose all that apply. |

Cytogenetics; FISH; Quantitative PCR; BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis; Other |

| 5 |

How frequently do you typically repeat cytogenetic analysis studies for monitoring response to Imatinib therapy? |

Every 3 months; Every 6 months; Every 12 months; Not routinely repeated; Other |

| 6 | How frequently do you typically repeat qRT-PCR for BCR-ABL for monitoring response to Imatinib therapy? | Every 3 months; Every 6 months; Yearly; Don’t utilize qRT-PCR |

| 7 |

How frequently do you typically repeat BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation studies for monitoring response to Imatinib therapy? |

When patients fail to achieve or lose their CyR; When patients fail to achieve or lose their hematologic response; When there is a 2-fold rise in BCR-ABL transcript levels; Never ordered the test; Unavailable; Not familiar with this test |

| 8 |

In a newly diagnosed 20-year old patient with chronic phase CML who has a matched related sibling, which of the following would you typically recommend? |

Imatinib 400 mg/day: Imatinib 600–800 mg/day; Allogeneic SCT; Interferon alpha; Other |

| 9 |

In a newly diagnosed 20-year old patient with chronic phase CML who has an unrelated matched donor, which of the following would you typically recommend? |

Imatinib 400 mg/day; Imatinib 600–800 mg/day; Allogeneic SCT; Interferon alpha; Other |

| 10 |

In a newly diagnosed 80-year old patient with chronic phase CML who has an unrelated matched donor, which of the following, would you typically recommend? |

Imatinib 400 mg/day; Imatinib 600–800 mg/day; Allogeneic SCT; Interferon alpha Hydroxyurea; Other |

| 11 |

In a patient with diagnosis of CML in chronic phase with a WBC of 225 × 109/L, how do you typically initiate therapy? |

Hydroxyurea until the WBC decreases significantly, then start imatinib; Start Imatini; Start Imatinib and hydroxyurea at the same time; Leukapheresis before imatinib; Leukapheresis and start imatinib; Other |

| 12 |

On a patient with CML in chronic phase in whom you started therapy with Imatinib but who has not achieved a complete hematologic response, at what point do you typically consider changing therapy? |

One Month; 2 months; 3 months; 6 months; 12 months; 18 months; Other |

| 13 |

On a patient with CML in chronic phase in whom you started therapy with Imatinib but who has not achieved any cytogenetic response (ie, still 100% Ph positive) at what point do you typically consider changing therapy? |

One Month; 2 months; 3 months; 6 months; 12 months; 18 months; Other |

| 14 |

On a patient with CML in chronic phase in whom you started therapy with Imatinib but who has not achieved a major cytogenetic response (ie, still >35% Ph positive), at what point do you typically consider changing therapy? |

One Month; 2 months; 3 months; 6 months; 12 months; 18 months; Other |

| 15 |

In a 70-year old patient with Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase on Imatinib 400 mg orally daily, which of the following strategies would you use routinely for monitoring response to Imatinib treatment? Please choose all that apply |

Blood counts; Cytogenetics; FISH; Quantitative PCR; Mutation analysis; Other |

| 16 |

In a 50-year old patient with Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML in chronic phase with a matched related sibling donor currently on Imatinib 400 mg daily, which of the following monitoring strategies would you use? Please choose all that apply. |

Blood counts; Cytogenetics; FISH; Quantitative PCR; Mutation analysis; Other |

| 17 |

In a patient with CML receiving therapy with Imatinib, which of the following would cause you to decide that the patient had experienced failure to therapy and should receive an alternative treatment? Please choose all that apply. |

At 3 months, no CHR; At 3 months, no CyR (ie, Ph+ 100%); At 6 months, no cytogenetic response (ie, Ph+ 100%); At 6 months, no major CyR (ie, Ph+ >35%); At 6 months, no CCyR (ie, Ph+ >0%); At 12 months, no CyR (ie. Ph+ 100%); At 12 months, no MCyR (ie, Ph+ >35%); At 12 months, no CCyR (ie, Ph+ >0%); At 12 months, no MMR (ie, <3-log reduction in BCR-ABL transcript levels); At 18 months, no CR (ie, Ph+ 100%); At 18 months, no MCyR (ie, Ph+ >35%); At 18 months, no CCyR (ie, Ph+ >0%); At 18 months, no MMR (ie, <3-log reduction in BCR-ABL transcript levels); At 18 months, no MMR (ie, <3-log reduction in BCR-ABL transcript levels); 2-fold rise in QPCR while in CCyR; ≥1 log rise in QPCR while in CCyR; Loss of CHR; Loss of CCyR; Loss of MCyR; None of the above |

| 18 |

Do you make a distinction between patients with failure to Imatinib and patients with suboptimal response to Imatinib? |

Yes, suboptimal response is a distinct entity; No, suboptimal response is the same as failure; No, patients are either failing or not |

| 19 |

If you do recognize suboptimal response as a separate entity, which of the following do you consider criteria for suboptimal response? Please choose all that apply. |

At 3 months, no CHR; At 3 months, no CyR (ie, Ph+ 100%); At 6 months, no cytogenetic response (ie, Ph+ 100%); At 6 months, no major CyR (ie, Ph+ >35%); At 6 months, no CCyR (ie, Ph+ >0%); At 12 months, no CyR (ie, Ph+ 100%); At 12 months, no MCyR (ie, Ph+ >35%); At 12 months, no CCyR (ie, Ph+ >0%); At 12 months, no MMR (ie, <3-log reduction in BCR-ABL transcript levels); At 18 months, no CR (ie, Ph+ 100%); At 18 months, no MCyR (ie, Ph+ >35%); At 18 months, no CCyR (ie, Ph+ >0%); At 18 months, no MMR (ie. <3-log reduction in BCR- ABL transcript levels); 2-fold rise in QPCR while in CCyR; ≥1 log rise in QPCR while in CCyR; Loss of CHR; Loss of CCyR; Loss of MCyR; None of the above |

| 20 |

On a 50-year old patient with a matched sibling donor who in your opinion has experienced failure to Imatinib 400 mg daily, what is your preferred course of action: |

Increase the dose of Imatinib to 600mg; to 800mg; Change therapy to Dasatinib to Nilotinib; Stem cell transplantation; Other clinical trials; Other |

| 21 |

On a 50-year old patient with a matched sibling donor who in your opinion has experienced suboptimal response to Imatinib 400 mg daily, what is your preferred course of action: |

Increase the dose of Imatinib to 600mg; to 800mg; Change therapy to Dasatinib; to Nilotinib; Stem cell transplantation; Other clinical trials; Other |

| 22 |

If you decide to increase the dose of Imatinib, how long do you try this approach before considering a change in therapy if not responding: |

3 months; 6 months; 12 months; 18 months; 24 months; Other |

| 23 |

For patients with suboptimal response to Imatinib do you typically assess for BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations? |

Yes; No |

| 24 |

For a 60-year old patient with CML who has failed Imatinib (using your standard criteria), and who has a matched related sibling. which of the following treatment options would you typically choose next? |

Allogeneic SCT; Dasatinib; Nilotinib; Low dose IFN, AraC, hydroxyurea, or combination of these; Other investigational strategy |

| 25 |

For a 60-year old patient with CML who has failed Imatinib (using your standard criteria), who has a matched unrelated donor, which of the following treatment options would you choose next? |

Allogeneic SCT; Dasatinib; Nilotinib; Low dose IFN, AraC, hydroxyurea, or combination of these; Other investigational strategy |

| 26 |

For a 35-year old with a matched sibling who is receiving Imatinib 400mg daily for CML in CP who is in complete cytogenetic remission and had achieved a major molecular response and now has a 5-fold increase in transcript levels and has lost major molecular response (but still in complete cytogenetic remission) your preferred course of action would be: |

Continue therapy unchanged; Increase the dose of Imatinib to 600mg daily; to 800 mg daily; Change therapy to Dasatinib; to Nilotinib; to stem cell transplant |

| 27 | In the case of this 35-year old patient, would you assess for mutations: | Yes; Would like to, but not available; No, only if the patient has lost cytogenetic or hematologic response ; Not in any instance |

| 28 | How would you use the information obtained from assessing mutations? Please choose all that apply. | Keep as background information only; Change therapy to a new TKI only if mutation is present; Select new TKI based on mutation detected; Transplant the patient if T315I found; Transplant the patent if P-loop found; Increase the dose only if not mutation identified; Other |

| 29 | How do you usually assess Imatinib-associated toxicity in your patients? | Frequent physician visits; Frequent nurse visits; Toxicity questionnaire completed by patients; Telephone query performed by nurse; Other |

| 30 |

Which, of the following Imatinib toxicities have you encountered in your patients with CML? Please check all toxicities as either “Ever encountered” or “Never encountered” |

CML indicates chronic myeloid leukemia; SCT, stem cell transplantation; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IFN, interferon; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; QPCR, Quantitative PCR; CHR, complete hematologic response; CyR, cytogenetic response; MCyR, major CyR; CCyR; CCyR, complete CyR; Ph, Philadelphia chromosome

Six-hundred and fifty physicians from 16 Latin American countries were contacted between May and August 2008, and 435 (67%) completed the survey. Responding physicians were distributed among countries as follows: Brazil (100), Mexico (75), Argentina (50), Colombia (50), Venezuela (40), Peru (30), Chile (20), Panama (9), Nicaragua (9), El Salvador (8), Costa Rica (8), Guatemala (8), Honduras (8), Bolivia (7), Ecuador (7), and Uruguay (6).

RESULTS

Physician and Practice Characteristics

The first section of the questionnaire was aimed at defining the characteristics of the participating physicians and their practices. Most respondents characterized their medical practice as non-academic (85%), including combined medical settings (35%), state hospitals (25%), private hospitals (23%), or other settings (2%). Ninety-three percent of the survey participants described their specialty as hematology, with the reminder classified as onco-hematology. This correlates with 82% of respondents describing their clinical practice as primarily composed of hematologic patients (including patients with both benign and malignant disease), while 10% of the respondents’ clinical practice was comprised of patients with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, 7% mentioned only treating patients with hematologic malignancies, and the remaining 1% of respondents described their primary practice as primarily comprised of patients with solid tumors. At the time of the survey, most physicians, were directly involved in the management of between 2–5 CML patients (31%) or 6–10 CML patients (30%); while another 18% of participants managed >20 CML patients. Forty-two percent of participants had >20 years of clinical experience since completing their specialty training and 56% had ≤10 years.

Availability of TKIs

Among all responders, 85% reported that imatinib was available to them only as front-line therapy for CML in their specific country while 8% reported it was approved only in the setting of IFN-α failure and 7% reported it available both as front-line and after IFN-α failure. At the time of the survey, 79% and 45% of physicians reported approval of the second-generation TKIs dasatinib and nilotinib in their country, respectively, with 42% reporting approval of both agents. At least one of these second-generation TKIs had received approved in all of the countries represented in this analysis. Overall, 66% of the participants answered that the majority of their CML patients received state coverage for imatinib therapy. Private insurance, organizations or charity, and self-pay accounted for the remaining 18%, 10%, and 5% of imatinib coverage, respectively.

General Disease Management

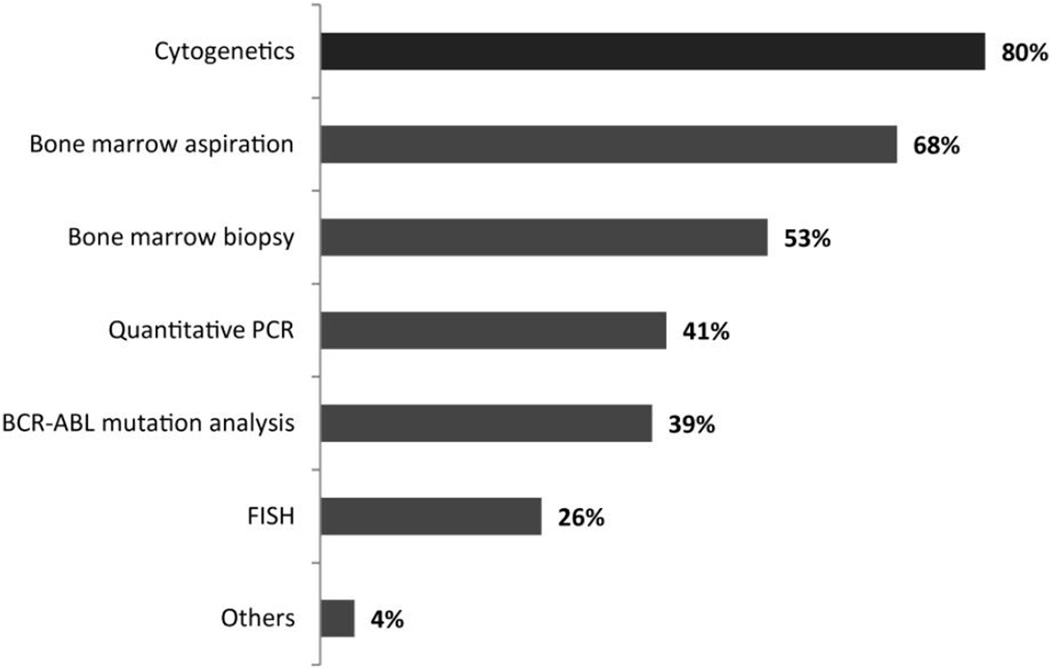

Participants were then asked several questions regarding their current management of CML. For initial work-up of a patient with suspected CML, physicians reported most commonly performing cytogenetic analysis (78%), bone marrow aspiration (68%) and bone marrow biopsy (53%) as initial diagnostic tests. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (41%), BCR-ABL mutation analysis (39%), and FISH (26%) were performed less frequently (Figure 1). In most instances, conventional cytogenetic or FISH analyses were performed at a nearby institution or hospital within their country (40%), while commercial laboratories and in-house hospital laboratories were used in 26% and 25% of cases, respectively. A smaller proportion (8%) sent cytogenetic or FISH samples to a hospital or institution in another country. Similar results were obtained when the respondents were queried on where they obtained a quantitative PCR or BCR-ABL mutation test.

Figure 1.

Initial diagnostic evaluation for patients with a clinical picture compatible with CML. (n= 435)

Q3 - When evaluating a patient with a white cell count (eg, 65,000) and a morphologic picture compatible with CML, which of the following initial diagnostic tests would you typically perform?

Physicians were also asked what features they considered representative of advanced phase CML. The criteria most frequently used to define accelerated phase was “blasts ≥10% in peripheral blood and/or bone marrow”, identified by 61% of respondents. Other commonly identified criteria for accelerated phase were “blasts ≥15% in peripheral blood and/or bone marrow” (49%) and “clonal evolution during the course of therapy” (48%). Blasts ≥20% in peripheral blood and/or bone marrow was considered to represent blast phase by 66% of responders while 44% considered ≥30% blasts to define this stage. Only one-third (33%) identified extramedullary disease as a representative feature of blast phase CML.

Initial Therapeutic Strategy

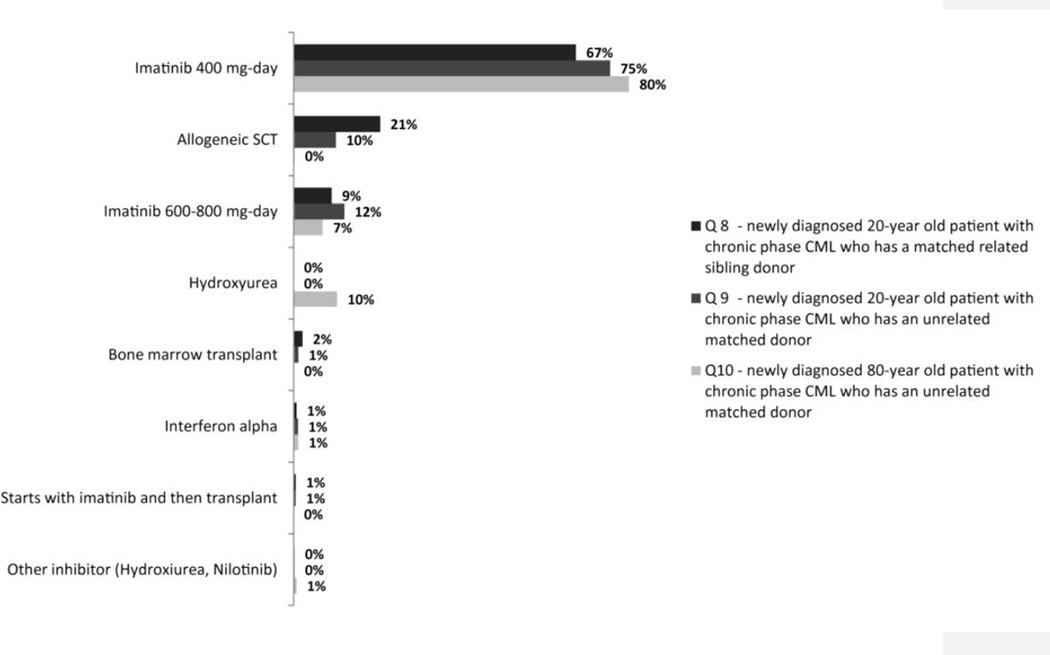

The next sets of questions in the survey were aimed at gathering information on the preferred diagnostic and treatment options. For this purpose, several hypothetical clinical scenarios were presented to the participants. Regardless of the patient’s age or donor status, imatinib 400 mg/day was found to be the preferred front-line therapy among Latin American physicians for newly diagnosed, chronic phase CML patients (Figure 2). For example, 67% and 75% of respondents scored imatinib (400 mg/day) as their primary choice of therapy for a newly diagnosed 20-year-old patient with either a related or a matched unrelated donor (MUD), respectively. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation was the second most favored option (20%) for the patient with a sibling donor, whereas high-dose imatinib was the second choice in the patient with a MUD. Although 80% of physicians listed imatinib 400 mg/day as their first choice of therapy for an 80-year-old patient with newly diagnosed CML, 10% would only use hydroxyurea.

Figure 2.

Preferred front-line treatment in different hypothetical case scenarios (n= 435)

Respondents were also presented with a case of a patient with chronic phase CML with a white blood cell count (WBC) of 225 × 109/L. In this case, 63% of respondents would use hydroxyurea until the WBC decreased significantly, and then start imatinib. Only 17% would initiate therapy with imatinib and 3% would use imatinib and hydroxyurea simultaneously.

Monitoring During Treatment

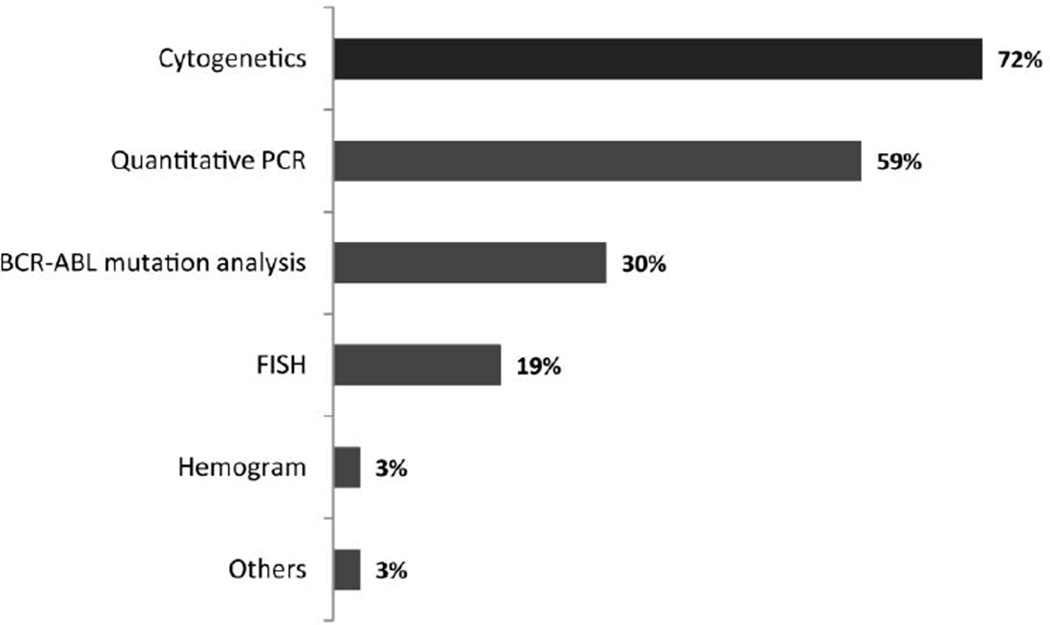

To monitor patients with CML treated with imatinib, besides complete blood counts, 72% reported routinely using cytogenetic analysis, 59% qPCR, 30% mutation analysis, and 19% FISH (Figure 3). Cytogenetic analyses are repeated every 6 months by 54% of participants while 31% repeat it every 3 months and 9% only annually. qRT-PCR was reported to be performed every 6 months by 41% every 3 months by 31%. Thirteen percent of participants reported never using qPCR. Mutation analysis was used by 33% of physicians when a patient lost or failed to achieve a hematological response, while 26% identified loss or failure to achieve a CCyR as the reason for performing this test. A ≥2-fold rise in BCR-ABL transcript levels was identified as a reason to perform mutation analysis by 19% of participants. Study participants were also given two specific case scenarios being managed with imatinib to investigate any differences in monitoring approach: a 50-year-old patient with a sibling donor and a 70-year-old patient. No differences in monitoring strategies were identified, with cytogenetic analysis being used routinely by 64% and 65%, respectively, and qPCR by 55% and 47%.

Figure 3.

Tests routinely performed to monitor response to imatinib therapy (n = 435)

Q4-In addition to peripheral blood counts, which of the following do you routinely use in monitoring response to imatinib therapy?

Management of Suboptimal Response

Physicians were then presented with different clinical scenarios to determine whether they consider a difference between failure to therapy and suboptimal response, and the criteria used to classify these states. Two-thirds (67%) of participants considered the distinction between failure and suboptimal response, to be clinically relevant. Among the physicians who did acknowledge a difference, 37% identified no major cytogenetic response (MCyR) at 6 months as a criterion to define suboptimal response. Other criteria frequently chosen to describe a suboptimal response include no cytogenetic response (i.e., 100% Ph-positive) at 6 months, no complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) at 6 months, and no complete hematologic response (CHR) at 3 months. When presented with a patient having a suboptimal response, 55% of participants would assess for a BCR-ABL mutation.

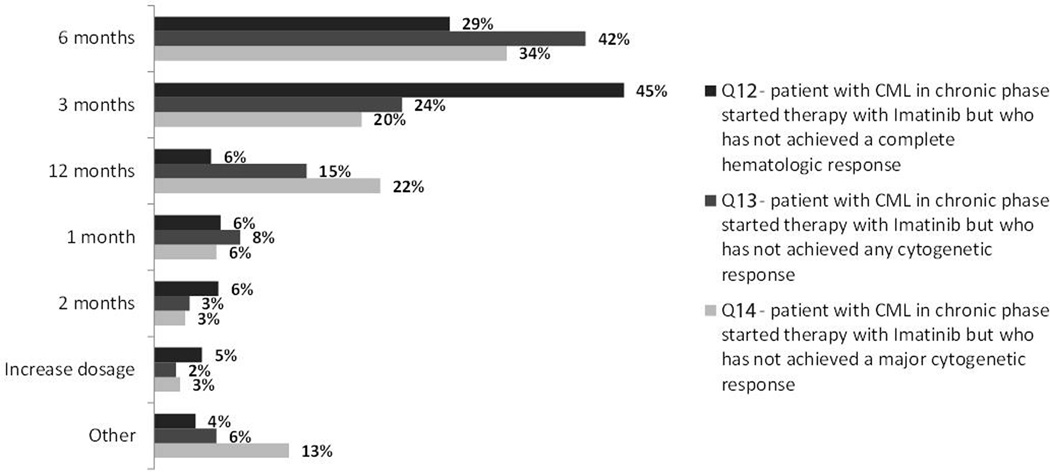

We then assessed the timing that physicians consider relevant for different responses. Failure to achieve a CHR at 3 months was considered a criterion to change therapy by 45% of respondents, while 29% would consider this only after 6 months (Figure 4). Similarly, for patients still 100% Ph+ at different times, 42% and 24% stated they would consider changing treatment at 3 and 6 months, respectively. However, for a patient achieving only a PCyR, 34% would consider changing if this was the best response at 6 months, compared to 22% if this was at 12 months, and 20% at 3 months.

Figure 4.

Timing for treatment change (n= 435)

When asked about the preferred course of action for managing a 50-year-old patient with a matched sibling donor and a suboptimal response to imatinib, 72% of participants would increase the imatinib dose (46% to 600 mg/day and 26% to 800 mg/day), while 16% would change therapy to dasatinib and 3% to nilotinib. Among those opting for a dose increase, 54% would try this strategy for a minimum of 3 months, 38% for 6 months, and 4% for 12 months.

Management of Imatinib Failure

When asked to identify clinical scenarios that defined imatinib treatment failure, loss of CCyR (39%), no CHR at 3 months (39%), loss of CHR (39%), no cytogenetic response at 6 months (38%), loss of a MMR (36%), and no MCyR at 6 months (34%) were most frequently reported (Table 2). Presented with hypothetical cases of imatinib failure, age of the patients influenced the choice of therapy. When evaluating the options for a 50-year-old and a 35-year-old patient, increasing the dose of imatinib was preferred by 61% (37% to 600 mg/day, 24% to 800 mg/day) for the older patient and 48% for the younger patient (30% to 600 mg/day and 18% to 800 mg/day). In both cases, second-generation TKIs would be the preferred option for only 24% and 22% respectively, whereas ASCT would be offered more frequently to the younger (12%) than the older (7%) patient. However, in the case of a patient of more advanced age (60 years old), the preferred course of action was reported to be a switch of the treatment to a second-generation TKI, regardless of donor status (82% in an older patient with a matched sibling donor, 85% in an older patient with a MUD).

Table 2.

Considering suboptimal response or failure to imatinib treatment (n= 435)

| Criteria | Suboptimal response to treatment |

Failure to treatment |

|---|---|---|

| At 6 months, no major cytogenetic response (ie, Ph+ >35%) | 37% | 34% |

| At 6 months, no cytogenetic response (ie, Ph 100%) | 29% | 38% |

| At 6 months, no complete cytogenetic response (ie, Ph+ >0%) | 26% | 26% |

| At 3 months, no CHR | 26% | 39% |

| At 3 months, no cytogenetic response (ie, Ph 100%) | 19% | 17% |

| Loss of CHR | 17% | 39% |

| Loss of CCyR | 17% | 39% |

| At 12 months, no complete cytogenetic response (ie, Ph+ >0%) | 17% | 25% |

| At 12 months, no major cytogenetic response (ie, Ph+ >35%) | 16% | 29% |

| Loss of MCyR | 16% | 36% |

| At 18 months, no major molecular response (ie, <3-log reduction in BCR-ABL transcript levels) |

15% | 26% |

| At 12 months, no cytogenetic response (ie, Ph 100%) | 14% | 33% |

| At 12 months, no major molecular response (ie, <3-log reduction in BCR-ABL transcript levels) |

12% | 23% |

| At 18 months, no complete cytogenetic response (ie, Ph+ >0%) | 10% | 23% |

| ≥1 log rise in QPCR while in CCyR | 10% | 17% |

| 2-fold rise in QPCR while in CCyR | 9% | 21% |

Q17 - In a patient with CML receiving therapy with imatinib, which of the following would cause you to decide that the patient had experienced failure to therapy and should receive an alternative treatment?

Participants were also presented with a hypothetical 35-year-old patient with a matched sibling who lost MMR but remained in CCyR while on imatinib 400 mg/day. In this setting, 54% of physicians would perform a mutation analysis. Of these, 40% would select a new TKI based on mutations detected, and 19% would increase the dose of imatinib if no mutation was identified. Interestingly, in the case of a 50 year old patient failing imatinib treatment, only 27% of respondents who would preferably switch treatment to a 2nd generation TKI, would perform BCR-ABL mutations.

Imatinib Toxicity

Imatinib was perceived to be overall well tolerated. Over half (58%) of the study participants reported that only 1%–2% of their patients were intolerant to imatinib and would need to change therapy because of intolerance. Conversely, 4% of physicians felt that more than 10% of their patients would be intolerant to imatinib. Nonetheless, imatinib is occasionally associated with significant toxicity. The most frequently observed imatinib toxicities encountered in the participant’s patients included neutropenia (75%), thrombocytopenia (74%), fluid retention (67%), nausea/vomiting (66%), anemia (64%), periorbital edema (61%), muscle cramps (57%), fatigue (57%), and weight gain (56%) (Table 3). The most common cause of treatment interruptions were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia (in 33%, 30%, and 11%, respectively). Physicians reported permanent treatment discontinuation for toxicity in 5%–12% of cases. Physicians ranked the three most common toxicities which have caused them to permanently discontinue imatinib therapy in their patients (Table 3). Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were most commonly ranked as the first and second most frequent toxicities. Other toxicities that physicians identified as leading to treatment discontinuation included fluid retention (67%), nausea and vomiting (66%), and anemia (64%).

Table 3.

Most frequently observed imatinib toxicities (n= 435)

| N° of respondents |

Toxicities encountered |

Caused interruption of Imatinib |

Caused discontinuation of Imatinib |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutropenia | 328 | 75% | 33% | 12% |

| Thrombocytopenia | 320 | 74% | 30% | 11% |

| Fluid retention | 293 | 67% | 5% | 1% |

| Nausea and vomiting | 288 | 66% | 8% | 6% |

| Anemia | 280 | 64% | 11% | 7% |

| Periorbital edema | 266 | 61% | 7% | 2% |

| Muscle cramps | 247 | 57% | 7% | 3% |

| Fatigue | 246 | 57% | 6% | 1% |

| Weight gain | 245 | 56% | 4% | - |

| Diarrhea | 205 | 47% | 6% | 4% |

| Bone aches | 199 | 46% | 5% | 3% |

| Rash | 183 | 42% | 12% | 9% |

| Liver dysfunction | 140 | 32% | 21% | 14% |

| Pleural effusion | 47 | 11% | 15% | 13% |

| Pericardial effusion or pericarditis |

36 | 8% | 17% | 6% |

| Congestive heart failure | 33 | 8% | 27% | 6% |

Q30. Which, of the following imatinib toxicities have you encountered in your patients with CML? Which of these toxicities that you have encountered have caused you to interrupt (I), dose reduce (R), or discontinue (D) Imatinib therapy?

Patient case studies were then presented to assess physician’s approach to imatinib-associated hematological toxicity. For a 45-year-old patient who developed a neutrophil count of 1.2 × 109/L while receiving imatinib (400 mg/day), participants were roughly equally divided among those who would stop therapy until neutrophil count recovered to ≥1.5 × 109/L and then would re-start at a reduced dose (32%), those who would discontinue therapy until neutrophil count recovered to ≥1.5 × 109/L and then would re-start imatinib at the same dose (21%); and those who would decrease the imatinib dosage to 300 mg/day without treatment interruptions (20%). Further, most participants reported considering a treatment interruption in patients when the neutrophil count reached either <0.5 × 109/L (33%) or <1.0 × 109/L (43%). The therapeutic management of imatinib-related thrombocytopenia was also evaluated, and most physicians reported discontinuing imatinib therapy when platelet count reached either <20 × 109/L (26%) or <50 × 109/L (49%); 22% of them would discontinue treatment with platelet counts <75 × 109/L (8%) and <100 × 109/L (14%).

DISCUSSION

The development of imatinib and other second-generation TKIs for the treatment of CML have greatly improved patient outcomes, and served as important examples of the clinical benefit of targeted therapies. Recommendations have been developed for the optimal management of patients with CML. The extent to which these recommendations are followed in practice is not known. Elements such as economic limitations, educational differences, and availability of drugs and laboratory tests may affect the extent to which these recommendations are followed. Recently, Kantarjian and colleagues3 surveyed 956 eligible physicians from the United States and Europe to assess patterns of practice in the United States and in Europe. In that study, the investigators concluded that although the practice patterns among those physicians in general were aligned with current guidelines and recommendations, important differences do exist. Because there are considerable differences in health care access and practice between developing countries and European countries and the United States, we investigated the practice patterns of physicians throughout 16 Latin American countries.

Availability of diagnostic and monitoring tools varied depending on the type of institution. For example, non-academic physicians were more likely to send FISH and cytogenetic samples to another institution or hospital within their country, while academic physicians were more likely to utilize an in-house hospital or institution laboratory. These practices are very similar with those observed in the US/Europe study3. However, an important difference revealed in this current study is that nearly 10% of Latin American physicians are required to rely on institutions based in other countries in order to perform these basic disease management tests.

Some monitoring practices were notable. Among them, 39% of responders indicated they would use mutational analysis at the time of diagnosis and 55% would test for BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations when managing a patient with a suboptimal response to imatinib treatment. These rates may reflect the intent more than actual practice, since most physicians indicated that they do not have direct access to mutational analysis at their institution. Interestingly, the US/European study by Kantarjian and colleagues reported that U.S. respondents in general were not familiar with BCR-ABL mutation tests3. That survey was done more than 3 years ago, when the availability and understanding of the clinical significance of such tests was in its early days. With the broader use of second generation TKI, this has clearly changed.

Regarding the management of patients, the survey reflects the change in practice that resulted from the introduction of TKI, with imatinib widely favored as initial therapy. Interestingly, 20% of responders would select a stem cell transplant to manage a 20-year old patient with a matched related sibling. The use of transplant has decreased significantly in recent years and nearly all patients throughout the world are offered imatinib as initial therapy. However, investigators in Mexico have published on the favorable results with their stem cell transplant approach and have emphasized the potential cost advantages of a transplant over the long-term use of imatinib4. The cost of standard dose of imatinib in Latin America is similar to that in the United States, although there is great variability based on the variability in access programs available in different countries (eg, state coverage, the Gleevec International Patient Assistance Program –GIPAP-, etc). The study by Ruiz-Argüelles et al. reported that the median cost of a non-myeloablative transplant (first 100 days) in Mexico was US$18,000, and US$30,000 for a conventional allograft. Subsequent costs are highly variable depending on complications. In contrast, the median cost of standard-dose imatinib in that country was reported as US$100.4 Thus, the cost of the first 100 days of transplant would cover 180 days of imatinib. Long term comparisons of the costs would depend on the complications associated with transplant, but it was suggested that a successful transplant with no or minimal long-term complications could have an economical edge. Despite this potential advantage, there are several reasons why transplant may not have been considered as initial therapy in more patients. These include the availability of donors as well as the local availability of transplantation or the experience with this procedure that may not be as favorable as those reported in other places. Wide availability and coverage of imatinib for all patients in need such as occurs for most patients in Brazil, Costa Rica, Panama, Uruguay, and Venezuela according to the responders from these countries would likely influence the selection of this therapy, particularly if it is perceived to be effective and non toxic. Interestingly, 10% of participants would treat an 80-year-old patient only with hydroxyurea.

The approach at changing therapy for patients receiving imatinib suggested some impatience in waiting for an adequate response. Forty-two percent of responders stated they would consider a change of therapy if there was no cytogenetic response after 3 months of therapy or no complete cytogenetic response at 6 months. These approaches would be more aggressive than what is recommended by the European Leukemia Net1. Regarding patients meeting definitions for failure, 48% and 61% of responders indicated that their preferred course of action would be imatinib dose escalation for patients age 35-years and 50-years, respectively, with less than 25% deciding to switch to a second generation TKI. The recommendations from the European Leukemia Net published in 2006 had this approach as one of the possible alternatives to consider. However, soon after that the results with dasatinib and nilotinib after imatinib failure have established these agents as the treatment of choice for such patients, with evidence form a randomized trial suggesting that the outcome after change to second generation TKI would be superior to that with dose escalation of imatinib5. However, second generation TKIs were not yet widely available throughout Latin America. Among responders, 14% reported not having dasatinib and 44% did not have nilotinib available for their patients. In this case, dose escalation is an adequate option, and recent reports suggest that with this approach CCyR can be achieved in approximately 40% of patients, particularly those who lost a cytogenetic response to imatinib6,7. Despite initial concerns about the durability of response, some of the responses are indeed durable, with EFS at 2 years of 85%7. Interestingly, change to a second generation TKI was greatly favored (80% of responders) for an older patient (age 60 years) over dose escalation. One possible explanation for this difference could be a concern about tolerability of higher dose imatinib among older patients. Of note, stem cell transplant was selected as second line therapy by very few physicians, even for the younger patients.

In this study, a high rate of Latin American physicians (93%) reported that they preferred to conduct frequent visits with their patients to monitor for imatinib-associated toxicities. This rate was similar to the 90% of U.S. physicians and 97% of European physicians who reported a similar practice3. In this study, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were some of the most common toxicities triggering treatment discontinuation for Latin American physicians. Comparatively, a smaller proportion of U.S./European physicians rated neutropenia (6% and 11% of U.S and European respondents) or thrombocytopenia (8% and 10% of U.S. and European respondents) as leading to treatment discontinuation. In contrast, congestive heart failure, pericardial effusion or pericarditis, pleural effusions, and liver dysfunction were the most frequently cited toxicities leading to treatment discontinuation for U.S./European physicians.

We conclude that the management of patients with CML frequently deviates from the recommendations published in the literature. The causes of these deviations are variable and should be investigated. Regional economical, cultural, and other factors should be considered and integrated into guidelines that may be applicable to different areas of the world with the aim of improving the outcome of all patients with CML.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement of Support: This work was supported in part by and unrestricted grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals

P30 CA016672, Ronald DePinho.

JC received research support from Novartis, BMS and Wyeth; MA received research support from BMS; CB received research support from Novartis; KP received research support from Novartis; RP received honoraria from Novartis, Bristol Myers and Schering.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: CD has nothing to disclose; IB has nothing to disclose; AE has nothing to disclose; NH has nothing to disclose; LM has nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baccarani M, Saglio G, Goldman J, et al. Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2006;108:1809–1820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deininger M, Buchdunger E, Druker BJ. The development of imatinib as a therapeutic agent for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;105:2640–2653. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian HM, Cortes J, Guilhot F, Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Lokey L. Diagnosis and management of chronic myeloid leukemia: a survey of American and European practice patterns. Cancer. 2007;109:1365–1375. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, Tarín-Arzaga LC, González-Carrillo ML, et al. Therapeutic choices in patients with Ph1 (+) chronic myelogenous leukemia living in Mexico in the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) era: stem cell transplantation or TKI’s? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:23–28. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian H, Pasquini R, Lévy V, et al. Dasatinib or high-dose imatinib for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia resistant to imatinib at a dose of 400 to 600 milligrams daily: two-year follow-up of a randomized phase 2 study (START-R) Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1002/cncr.24504. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarjian HM, O'Brien S, Cortes JE, et al. Complete cytogenetic and molecular responses to interferon-alpha-based therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia are associated with excellent long-term prognosis. Cancer. 2003;97:1033–1041. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Jones D, et al. Imatinib mesylate dose escalation is associated with durable responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia after cytogenetic failure on standard-dose imatinib therapy. Blood. 2009;113:2154–2160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarjian H, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. High-dose imatinib mesylate therapy in newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:2873–2878. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]