Abstract

Aims

p‐Synephrine is a protoalkaloid widely used in dietary supplements for weight management because of its purported thermogenic effects. However, there is a lack of scientific information about its effectiveness to increase fat metabolism during exercise. The purpose of this investigation was to determine the effects of an acute ingestion of p‐synephrine on fat oxidation at rest and during exercise.

Methods

In a double‐blind, randomized and counterbalanced experimental design, 18 healthy subjects performed two acute experimental trials after the ingestion of p‐synephrine (3 mg kg−1) or after the ingestion of a placebo (cellulose). Energy expenditure and fat oxidation rates were measured by indirect calorimetry at rest and during a cycle ergometer ramp exercise test (increases of 25 W every 3 min) until volitional fatigue.

Results

In comparison with the placebo, the ingestion of p‐synephrine did not change energy consumption (1.6 ± 0.3 vs. 1.6 ± 0.3 kcal min−1; P = 0.69) or fat oxidation rate at rest (0.08 ± 0.02 vs. 0.10 ± 0.04 g min−1; P = 0.15). However, the intake of p‐synephrine moved the fat oxidation–exercise intensity curve upwards during the incremental exercise (P < 0.05) without affecting energy expenditure. Moreover, p‐synephrine increased maximal fat oxidation rate (0.29 ± 0.15 vs. 0.40 ± 0.18 g min−1; P = 0.01) during exercise although it did not affect the intensity at which maximal fat oxidation was achieved (55.8 ± 7.7 vs. 56.7 ± 8.2% VO2peak; P = 0.51).

Conclusions

The acute ingestion of p‐synephrine increased the fat oxidation rate while it reduced the carbohydrate oxidation rate when exercising at low‐to‐moderate exercise intensities.

Keywords: bitter orange, Citrus aurantium, fat metabolism, nutrition, stimulant

What is Already Known about this Subject

p‐Synephrine is a phenylethylamine derivative naturally present in bitter orange (Citrus aurantium).

This substance can also be synthesized in the human body using the same pathways involved in the synthesis of catecholamines.

p‐Synephrine is a substance typically included in weight loss products because it might induce significant increases in basal metabolic rate and lipolysis by activation of the β3 adrenergic receptors.

What this Study Adds

The ingestion of 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine did not change energy consumption or fat oxidation rate at rest.

Acute consumption of p‐synephrine was effective to move the fat oxidation–exercise intensity curve upwards during the incremental exercise and increased maximal fat oxidation rate during exercise.

The metabolic effects found after the ingestion of p‐synephrine might be valuable for those individuals seeking increased fat oxidation during exercise.

Introduction

p‐Synephrine (4‐[1‐hydroxy‐2‐(methylamino)ethyl]phenol) is a phenylethylamine derivative naturally present in bitter orange (Citrus aurantium) and many other citrus species such as Seville oranges, Nova tangerines and Marr's sweet oranges 1, 2. Moreover, p‐synephrine can be synthesized in the human body using the same pathways involved in the synthesis of catecholamines 3, although it is considered a trace amine due to its low plasmatic levels. p‐Synephrine has become popular as an alternative to ephedra after the banning of ephedrine‐containing dietary products by the Food and Drug Administration in 2004 4. This substance has been included, as p‐synephrine or as Citrus aurantium, in a multitude of foods and dietary supplements used for weight loss because of its purported thermogenic effect 5.

Previous investigations have demonstrated that acute 6 and chronic ingestions 7 of Citrus aurantium supplements – containing p‐synephrine among other sympathomimetic substances such as caffeine and octopamine – might induce increases in resting energy expenditure and lipolysis. Although it has been suggested that the thermogenic effect of Citrus aurantium might be related to the activation of the β3 adrenergic receptors induced by p‐synephrine 8, it is impossible to determine whether these effects are produced by the p‐synephrine contained in Citrus aurantium supplements or by the co‐ingestion of other active substances included in this type of supplements. The acute ingestion of p‐synephrine (21 mg or ~0.3 mg of p‐synephrine per kg of body mass), together with caffeine, produced a lower perceived exertion during 30 min of moderate intensity exercise 9. In addition, the ingestion of p‐synephrine (100 mg or ~1.2 mg kg−1 for 3 days) alone or with caffeine was effective at increasing the number of repetitions during a squat resistance test 10. On the other hand, the ingestion of p‐synephrine (3 mg kg−1) was ineffective at increasing jump height or running speed in elite sprinters during maximal running speed tests 11. However, the effects of acute p‐synephrine ingestion on substrate metabolism during exercise have not been investigated yet despite the use of p‐synephrine‐containing products in combination with exercise programmes for weight loss.

The aim of this investigation was to determine the effects of an acute dose of 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine on fat and carbohydrate metabolism at rest and during exercise of incremental intensity. Based on previous investigations at rest and with the use of Citrus aurantium supplements –that contained p‐synephrine among other active substances – we hypothesized that p‐synephrine would increase energy expenditure and fat oxidation rate during exercise in healthy participants.

Methods

Subjects

Eighteen young and healthy participants volunteered to participate in this investigation (age: 26.0 ± 7.2 years; body mass: 71.3 ± 7.36 kg; body height: 179 ± 7 cm and body mass index: 22.2 ± 1.9 kg m2). All participants were considered physically active because they had previous experience in endurance exercise activities such as running and cycling (~1 h day−1, ~3 days week−1) at least during the three previous years. All participants were non‐smokers, had no previous history of cardiopulmonary diseases and had suffered no musculoskeletal injuries in the previous 6 months. Participants were encouraged to avoid medications, nutritional supplements and sympathetic stimulants for the duration of the study and compliance was examined with dietary questionnaires. One week before the start of the study, participants were fully informed of the experimental standards and the risks and discomforts associated with the research and signed an informed written consent to participate in the investigation. The study was approved by the Camilo José Cela University Research Ethics Committee in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental design

A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomized and counterbalanced experimental design was used in this investigation. Each participant took part in two experimental trials separated by 3 days in order to allow complete recovery and p‐synephrine wash‐out. On one occasion, participants ingested 3 mg of p‐synephrine per kg of body mass (99% purity; Synephrine HCL, Nutrition Power, Spain) contained within an opaque capsule. This dosage was higher than previous investigations in which p‐synephrine 10 or Citrus aurantium supplements 9 were administered before exercise activities but it was based on a previous publication in which 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine had minimal side‐effects on elite sprinters 11. On another occasion, participants ingested an identical capsule filled with a placebo (cellulose). The capsules were ingested with 150 ml of tap water 60 min before the onset of the experimental trials. An alphanumeric code was assigned to each trial by a person independent to the study to blind participants and investigators to the substances tested. Environmental temperature and humidity were recorded using a digital temperature and humidity monitor (OH1001, OH Haus, Spain), and the average environmental conditions during testing were 20.3 ± 0.6°C air temperature and 44 ± 16% relative humidity.

Experimental protocol

Two days before the first experimental trial, participants were nude‐weighed to calculate the p‐synephrine dosage. Twenty‐four hours before each experimental trial, participants refrained from strenuous exercise and adopted a similar diet and fluid intake regimen. For this control, subjects were requested to complete a 24‐h dietary record on the day before the first laboratory visit and to follow the same dietary pattern before the second visit. Subjects were required to refrain from alcohol‐, caffeine‐, and citrus‐containing products and foods for 48 h before each laboratory visit. Participants were encouraged to attend in fasting‐state (at least 8 h before their last meal) prior to each experimental trial. Compliance with these experimental controls was verbally confirmed with the subjects before commencing each experimental session.

The day of the experimental trials, participants arrived at the laboratory at 09.00 and the capsule containing p‐synephrine or placebo was individually provided in unidentifiable bags. Participants were dressed in a T‐shirt and shorts, and a heart rate belt (PolarW, Finland) was attached to their chest. After that, they rested supine for 60 min to allow p‐synephrine/cellulose absorption. Later, gas exchange data were collected continuously for 15 min using an automated breath‐by‐breath system (Metalyzer 3B, Cortex, Germany) to calculate resting oxygen uptake (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2). During the last 5‐min of this collection period, the gas exchange data were averaged to achieve a representative value for these variables. For this measurement, participants remained lying still with no visual or acoustic stimulus. Certified calibration gases (16.0% O2; 5.0% CO2, Cortex, Germany) and a 3‐l syringe were used to calibrate the gas analyser and the flowmeter before each trial. During this period, resting heart rate was continuously measured and averaged for the same 5‐min period. Systolic blood pressure and fourth phase diastolic blood pressure were measured by triplicate on the left arm using an automatic sphygmomanometer (M6 Comfort, Omron, Japan) while the participant lay supine. An average of three blood pressure measurements was used for analysis.

After the resting measurements, participants performed a standardized warm‐up that included 10 min at 50 W on a cycle ergometer (SNT Medical, Cardgirus, Spain) and completed an incremental exercise test on the cycle ergometer that included increases of 25 W each 3 min until volitional fatigue (the initial workload was set at 50 W). Expired gases were collected with the same stationary breath‐by‐breath device used for the resting measurements (MetaLyzer 3B, Cortex, Germany) to calculate oxygen uptake (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) during exercise. During the incremental exercise intensity test, the VO2peak was defined as the highest VO2 value. The VO2peak was considered valid when the following end criteria were reached at the end of the test: the VO2 difference between the last two consecutive loads was less than 0.15 l min−1, the respiratory exchange ratio was higher than 1.10, the participant's rating of perceived exertion (6‐to‐20 point Borg scale) was higher than 19 points, while heart rate was great than 80% of the age‐adjusted estimate of maximal heart rate 12.

The same test with the identical workloads and times was used for the two experimental trials, while an individually chosen cadency (between 70 and 90 rpm for all participants) was replicated on both days. All subjects were familiarized with this test by performing a familiarization trial at least one week before the onset of the experimental trials. During the last minute of each stage, the gas exchange data were averaged every 15 s in order to achieve a representative value. Absolute exercise intensity (in W) was normalized by using the individual's VO2peak. For each individual, the measured variables were used to construct curves of energy rate and substrate metabolism rates vs. exercise intensity, expressed as %VO2peak, following a previous investigation by Achten et al. 13.

Calculations

The rates of energy expenditure and substrate oxidation (fat and carbohydrate) were calculated using the non‐protein respiratory quotient 14, 15. Energy expenditure (kcal min−1) at rest and during exercise was calculated as (3.869 × VO2) + (1.195 × VCO2), where VO2 and VCO2 are in l min−1. Fat oxidation rate (g min−1) was calculated as (1.67 × VO2) − (1.67 × VCO2) and carbohydrate oxidation rate (g min−1) was calculated as (4.55 × VCO2) − (3.21 × VO2) 14. The rate of maximal fat oxidation was individually calculated for each participant as the highest value of fat oxidation rate obtained during the incremental exercise intensity test. The exercise at which maximal fat oxidation was achieved was also obtained for each individual.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected as previously indicated and the results of each test were subsequently blindly introduced into the statistical package SPSS v20.0 and analysed. The normality of each quantitative variable was initially tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. All the quantitative variables included in this investigation presented a normal distribution (P > 0.05) and parametric statistics were used to determine differences between p‐synephrine and the placebo. A one‐way analysis of variance (anova) was used to compare the energy expenditure and carbohydrate and fat oxidation, heart rate and blood pressure at rest. A two‐way anova (treatment × load) was used to compare these variables during exercise. After a significant F‐test (Geisser–Greenhouse correction for the assumption of sphericity), differences between means were identified using Tukey's post‐hoc procedure. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. All data are presented as means ± standard deviation. The effect size (d) was calculated in all pairwise comparisons according to the formula proposed by Glass et al. 16. The magnitude of the effect size, in absolute values, was interpreted using the scale of Cohen 17: an effect size lower than 0.2 was considered as small, an effect size around 0.5 was considered as medium and an effect size over 0.8 was considered large. The criterion for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

In comparison with the placebo, the ingestion of 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine did not change resting VO2 or VCO2 values (Table 1; P > 0.05). Thus, energy expenditure and substrate metabolism at rest were unchanged by the ingestion of p‐synephrine. This substance did not modify heart rate or systolic and diastolic blood pressure at rest (P > 0.05). The effect sizes induced by the ingestion of p‐synephrine were small‐to‐moderate in all metabolic and cardiovascular variables measured at rest.

Table 1.

Metabolic and cardiovascular variables at rest one hour after the ingestion of p‐synephrine or a placebo. Data are mean ± SD for 18 healthy participants

| Resting values | Placebo | p‐synephrine | d | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO 2 ( l min −1 ) | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.42 |

| VCO 2 ( l min −1 ) | 0.28 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.64 |

| Energy expenditure ( kcal min −1 ) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.10 | 0.69 |

| Carbohydrate oxidation ( g min −1 ) | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.40 | 0.45 |

| Fat oxidation ( g min −1 ) | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.15 |

| Heart rate (beats min −1 ) | 56 ± 5 | 57 ± 6 | 0.18 | 0.53 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 123 ± 13 | 123 ± 13 | 0.22 | 0.82 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73 ± 9 | 74 ± 9 | 0.04 | 0.55 |

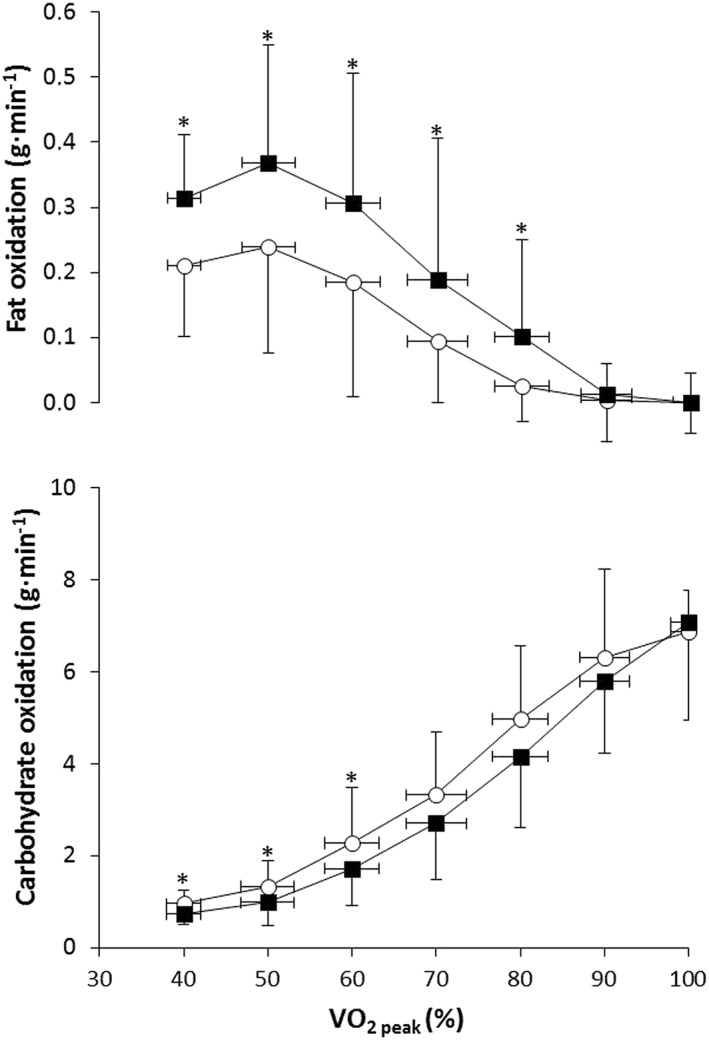

Figure 1 depicts energy expenditure rate and heart rate during the ramp exercise protocol. Both variables progressively increased with exercise intensity but p‐synephrine did not modify the energy expenditure–exercise intensity and heart rate–exercise intensity relationships (P > 0.05). Figure 2 depicts substrate oxidation during the ramp exercise protocol, obtained from VO2 and VCO2 values. The ingestion of p‐synephrine moved the fat oxidation–exercise intensity curve upwards during the incremental exercise protocol and produced significantly higher fat oxidation rates at 40, 50, 60, 70 and 80% of VO2peak when compared with the ingestion of the placebo (P < 0.05). Conversely, the ingestion of p‐synephrine shifted the carbohydrate oxidation–exercise intensity curve downwards with lower carbohydrate oxidation rates at all intensities ranging from 40 to 70% VO2peak (Figure 2; P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Energy expenditure (upper panel) and heart rate (lower panel) during exercise of increasing intensity 1 h after the ingestion of 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine or a placebo. Data are mean ± SD for 18 participants. ( ) Placebo, (

) Placebo, ( ) Synephrine

) Synephrine

Figure 2.

Fat (upper panel) and carbohydrate (lower panel) oxidation rate during exercise of increasing intensity 1 h after the ingestion of 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine or a placebo. Data are mean ± SD for 18 participants. *Different from placebo at P < 0.05 ( ) Placebo, (

) Placebo, ( ) Synephrine

) Synephrine

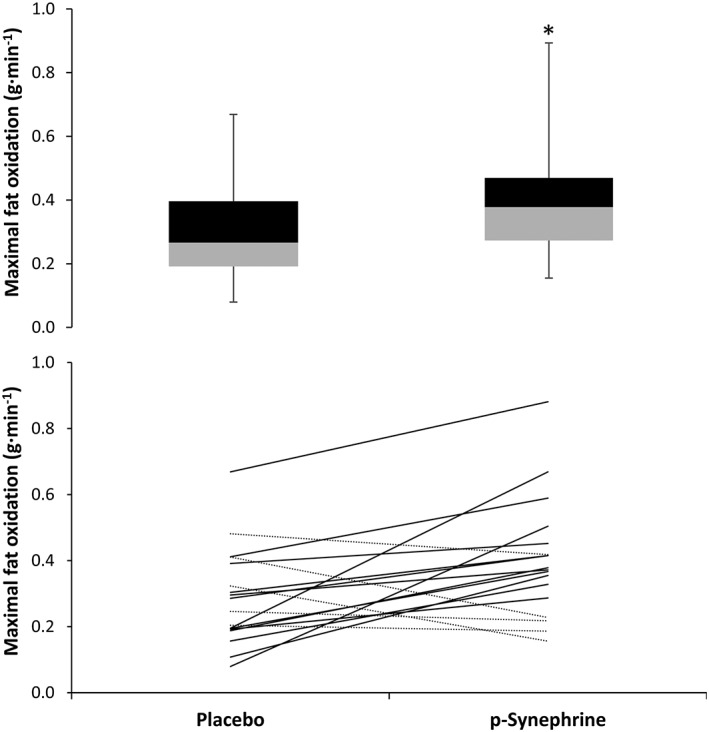

Figure 3 depicts group mean and individual values for maximal fat oxidation obtained during the experimental trials. On average, p‐synephrine increased maximal fat oxidation rate (0.29 ± 0.15 vs. 0.40 ± 0.18 g min−1; P = 0.01) with a moderate effect size (d = 0.79), over the values obtained with the ingestion of the placebo. However, the pre‐exercise ingestion of p‐synephrine did not affect the intensity at which maximal fat oxidation was achieved (55.8 ± 7.7 vs. 56.7 ± 8.2% VO2peak; P = 0.51, d = 0.01). Out of 18 participants, 13 (72% of the sample) obtained a higher maximal fat oxidation with p‐synephrine while the remaining five obtained a higher maximal fat oxidation with the ingestion of the placebo.

Figure 3.

Box‐and‐whisker plot (upper panel) and individual responses (lower panel) for maximal fat oxidation rates achieved during exercise of increasing intensity 1 h after the ingestion of 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine or a placebo. *Different from placebo at P < 0.05

Discussion

The use of Citrus aurantium and its main protoalkaloid constituent p‐synephrine has greatly increased in the last few years among exercise practitioners seeking body fat and body weight reduction due to the prohibition of ephedra‐ and ephedrine‐containing dietary supplements 4. However, investigations about the efficacy of p‐synephrine‐containing supplements on substrate metabolism are scarce and there is little information about the physiological outcomes derived from the combination of p‐synephrine and exercise. For this reason, this investigation aimed to determine the effects of an acute ingestion of a high dose of p‐synephrine on energy expenditure and substrate metabolism at rest and during exercise. The main outcomes of this investigation when compared to the ingestion of a placebo were: the p‐synephrine intake: (a) did not modify energy expenditure, fat and carbohydrate oxidation rate at rest, nor increase heart rate, systolic or diastolic blood pressure (Table 1); (b) significantly increased fat oxidation rate at the same relative workload at intensities ranging from low to moderate while it reduced carbohydrate utilization during exercise; (c) did not modify energy expenditure or heart rate during exercise of increasing intensity. In the light of these results, 3 mg kg−1 of p‐synephrine could be used as a supplement to increase fat oxidation during exercise of moderate intensity.

Few studies have been geared to elucidating the effectiveness of p‐synephrine intake on energy expenditure at rest 5. In some of them, multicomponent supplements containing Citrus aurantium increased resting metabolic rate after acute 6, 18, 19, 20, 21 or chronic ingestion of these types of supplements 7, 22. However, in most of these investigations, the experimental supplements contained other stimulants and sympathomimetic substances in addition to p‐synephrine, such as caffeine, a well‐recognized thermogenic substance 23. Thus, it is difficult to know whether to attribute this increased energy expenditure to p‐synephrine or the remaining substances included in the administered products. In the present investigation, we used a commercially available p‐synephrine supplement with a purity of 99%, while the ingestion of other stimulants was restricted to isolate the effects of p‐synephrine in the outcomes of this study. Interestingly, the ingestion of p‐synephrine did not change energy expenditure or the use of fat and carbohydrate at rest (Table 1), despite our dose (3 mg kg−1 equivalent to 214 mg of p‐synephrine) being much higher than that used in most (ranging from 12 to 100 mg of p‐synephrine 7, 9, 10, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22), but not all, previous investigations (216 mg of p‐synephrine 11). Thus, it is likely that the purported thermogenesis attributed to Citrus aurantium and other p‐synephrine‐containing supplements at rest 6, 7, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 is more related to other co‐ingredients included in this type of thermogenic supplements – such as caffeine – than to the isolated effects of p‐synephrine.

The efficacy of p‐synephrine to improve physical performance during exercise also remains unclear. The ingestion of p‐synephrine, in combination with caffeine, has been found effective to reduce perceived exertion during prolonged exercise of moderate intensity 9, while the intake of p‐synephrine alone, for three consecutive days, was effective to increase the number of repetitions during a resistance exercise test 10. On the other hand, the pre‐exercise ingestion of p‐synephrine was ineffective to increase jump height or maximal running speed of elite sprinters 11. In the current investigation we did not measure physical performance but we assessed substrate metabolism during exercise of increasing intensity. Interestingly, p‐synephrine did not modify energy expenditure or heart rate during exercise but it greatly modified substrate utilization at workloads between 40 and 80% of VO2peak (Figure 2). At these exercise intensities, the pre‐exercise intake of p‐synephrine shifted substrate utilization towards fat while it reduced the use of carbohydrates. The effect of p‐synephrine was not present at higher exercise intensities mostly due to the suppression of fat oxidation at high energy demands that reduced fat oxidation to ~0 g min−1 above 90% VO2peak, as previously found 13. The data of previous investigations about p‐synephrine and exercise performance, together with the data provided by the current study, suggest that p‐synephrine could be ‘ergogenic’ in aerobic exercise activities with certain reliance of fat metabolism (such as prolonged/moderate intensity exercise or resistance exercise 9, 10), while the effects of p‐synephrine would not be present in sprint‐based exercise activities in which fat oxidation is negligible 11.

Figure 2 indicates that the pre‐exercise ingestion of a high dose of p‐synephrine was able to increase whole‐body fat oxidation rate during exercise of low‐to‐moderate intensity, likely due to a higher use of fat in the mitochondria of active muscles. However, our investigation does not offer information about the exact mechanism related to this metabolic effect. It has been found previously that p‐synephrine has a poor binding affinity to α1, α2, β1 and β2 adrenergic receptors 8. However, p‐synephrine activates β3 adrenergic receptors that may be responsible for the increased fat utilization during exercise through modulation of lipolysis via the epinephrine‐ and norepinephrine‐induced activation of adenylate cyclase [19]. As this is the first investigation to determine the effects of p‐synephrine intake on substrate metabolism during exercise, there is a need for further investigations to discover the mechanism(s) responsible for the increased fat oxidation of this substance.

Numerous exercise physiology investigations have tried to determine the best circumstances to obtain the maximal fat oxidation rate (e.g., Fatmax) during exercise. Briefly, they have established the notion that Fatmax is normally obtained when exercising at moderate intensity, between 40 and 60% of VO2max 13, 24, while factors such as exercise duration 25, aerobic fitness 26, pre‐exercise meal 27 and ambient temperature 28 can substantially modify the amount of fat oxidized at a fixed workload. The current data indicate that p‐synephrine can aid to increase Fatmax as it augmented maximal fat oxidation rate by ~38% (Figure 3). However, p‐synephrine did not change the exercise at which Fatmax was obtained because Fatmax was obtained at ~56% VO2peak in both trials. Although increased Fatmax values were not present in all participants in this investigation (5 out of 18 participants did not benefit from p‐synephrine ingestion), this positive outcome might be valuable for those seeking increased fat utilization during exercise.

Conclusions

An acute p‐synephrine intake of 3 mg kg−1 in healthy and active participants had no effect on energy expenditure and substrate oxidation at rest, and heart rate and blood pressure remained unchanged under this condition. Nevertheless, this substance produced a noteworthy change in substrate utilization during exercise because it increased fat oxidation rate while it reduced carbohydrate oxidation rate when exercising at low‐to‐moderate intensities. In fact, p‐synephrine increased the maximal rate of fat oxidation by 0.11 ± 0.7 g min−1, which might represent an augmented fat utilization of 7 g of fat per hour of exercise despite exercising at the same intensity and at the same heart rate. However, it is necessary to determine the effects of long‐term administration of this substance on energy and substrate metabolism at rest and during exercise.

Competing Interests

Both authors declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

This investigation did not receive any funding. Jorge Gutierrez‐Hellín received a postgraduate studentship from the Camilo José Cela University.

The authors wish to thank the subjects for their invaluable contribution to the study.

Contributors

Both authors were responsible for formulating the research question, designing and carrying out the study and analysing the data. JDC wrote the article and JG‐H revised it.

Gutiérrez‐Hellín, J. , and Del Coso, J. (2016) Acute p‐synephrine ingestion increases fat oxidation rate during exercise. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 82: 362–368. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12952.

References

- 1. Pellati F, Benvenuti S. Fast high‐performance liquid chromatography analysis of phenethylamine alkaloids in citrus natural products on a pentafluorophenylpropyl stationary phase. J Chromatogr A 2007; 1165: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dragull K, Breksa AP 3rd, Cain B. Synephrine content of juice from Satsuma mandarins (Citrus unshiu Marcovitch). J Agric Food Chem 2008; 56: 8874–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rossato LG, Costa VM, Limberger RP, Bastos Mde L, Remiao F. Synephrine: from trace concentrations to massive consumption in weight‐loss. Food Chem Toxicol 2011; 49: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Food and Drug Administration . Dietary supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids adulterated because they present an unreasonable risk; final rule. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2004; 18: 95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stohs SJ, Preuss HG, Shara M. A review of the human clinical studies involving Citrus aurantium (bitter orange) extract and its primary protoalkaloid p‐synephrine. Int J Med Sci 2012; 9: 527–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gougeon R, Harrigan K, Tremblay JF, Hedrei P, Lamarche M, Morais JA. Increase in the thermic effect of food in women by adrenergic amines extracted from Citrus aurantium . Obes Res 2005; 13: 1187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colker CM, Kaiman DS, Torina GC, Perlis T, Street C. Effects of Citrus aurantium extract, caffeine and St John's wort on body fat loss, lipid levels and mood states in normal weight and obese individuals. Curr Ther Res 1999; 60: 145–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stohs SJ, Preuss HG, Shara M. A review of the receptor‐binding properties of p‐synephrine as related to its pharmacological effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2011; 2011: 482973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haller CA, Duan M, Jacob P 3rd, Benowitz N. Human pharmacology of a performance‐enhancing dietary supplement under resting and exercise conditions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 65: 833–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ratamess NA, Bush JA, Kang J, Kraemer WJ, Stohs SJ, Nocera VG, et al. The effects of supplementation with p‐synephrine alone and in combination with caffeine on resistance exercise performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2015; 12: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gutiérrez‐Hellín J, Salinero JJ, Abían‐Vicen J, Areces F, Lara B, Gallo C, et al. Acute consumption of p‐synephrine does not enhance performance in sprint athletes. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2016; 41: 63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Edvardsen E, Hem E, Anderssen SA. End criteria for reaching maximal oxygen uptake must be strict and adjusted to sex and age: a cross‐sectional study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e85276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Achten J, Gleeson M, Jeukendrup AE. Determination of the exercise intensity that elicits maximal fat oxidation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002; 34: 92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frayn KN. Calculation of substrate oxidation rates in vivo from gaseous exchange. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1983; 55: 628–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brouwer E. On simple formulae for calculating the heat expenditure and the quantities of carbohydrate and fat oxidized in metabolism of men and animals, from gaseous exchange (oxygen intake and carbonic acid output) and urine‐N. Acta Physiol Pharmacol Neerl 1957; 6: 795–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glass G, McGaw B, Smith M. Meta‐Analysis in Social Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sale C, Harris RC, Delves S, Corbett J. Metabolic and physiological effects of ingesting extracts of bitter orange, green tea and guarana at rest and during treadmill walking in overweight males. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006; 30: 764–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoffman JR, Kang J, Ratamess NA, Jennings PF, Mangine G, Faigenbaum AD. Thermogenic effect from nutritionally enriched coffee consumption. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2006; 3: 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stohs SJ, Preuss HG, Keith SC, Keith PL, Miller H, Kaats GR. Effects of p‐synephrine alone and in combination with selected bioflavonoids on resting metabolism, blood pressure, heart rate and self‐reported mood changes. Int J Med Sci 2011; 8: 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seifert JG, Nelson A, Devonish J, Burke ER, Stohs SJ. Effect of acute administration of an herbal preparation on blood pressure and heart rate in humans. Int J Med Sci 2011; 8: 192–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zenk JL, Leikam SA, Kassen LJ, Kuskowski MA. Effect of Lean System 7 on metabolic rate and body composition. Nutrition 2005; 21: 179–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hursel R, Westerterp‐Plantenga MS. Thermogenic ingredients and body weight regulation. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010; 34: 659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nordby P, Saltin B, Helge JW. Whole‐body fat oxidation determined by graded exercise and indirect calorimetry: a role for muscle oxidative capacity? Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006; 16: 209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Romijn JA, Coyle EF, Sidossis LS, Gastaldelli A, Horowitz JF, Endert E, et al. Regulation of endogenous fat and carbohydrate metabolism in relation to exercise intensity and duration. Am J Physiol 1993; 265: E380–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Del Coso J, Hamouti N, Ortega JF, Mora‐Rodriguez R. Aerobic fitness determines whole‐body fat oxidation rate during exercise in the heat. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2010; 35: 741–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Achten J, Jeukendrup AE. The effect of pre‐exercise carbohydrate feedings on the intensity that elicits maximal fat oxidation. J Sports Sci 2003; 21: 1017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Febbraio MA, Snow RJ, Stathis CG, Hargreaves M, Carey MF. Effect of heat stress on muscle energy metabolism during exercise. J Appl Physiol 1994; 77: 2827–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]