Abstract

Aim

Domperidone is preferentially used over other antiemetic agents to treat digestive symptoms in Parkinson's disease (PD). Concerns have been raised regarding an increased risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmia and sudden cardiac death (VT/SCD) associated with domperidone in the general population. However, the risk in PD is unknown.

Methods

We conducted a multicentre retrospective cohort study using administrative databases from seven Canadian provinces and the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Using a nested case–control analysis, we estimated the rate ratios (RRs) of VT/SCD associated with domperidone use compared to no use in patients newly‐diagnosed with PD. VT/SCD events were identified using administrative medical records and vital statistics with a manual review of all potential cases. Meta‐analytic methods were used to estimate overall effects across sites.

Results

Among 214 962 patients with PD, 2907 cases of VT/SCD were identified during 886 581 person‐years of follow‐up (incidence rate 3.28 per 1000 persons per year). Current use of domperidone was associated with a non‐statistically significant 22% increased risk of VT/SCD (RR 1.22; 95% CI 0.99–1.50) compared with no use. The risk was significantly elevated in those with a history of cardiovascular disease (RR 1.38; 95% CI 1.07–1.78), but not in those without (RR 1.21; 95% CI 0.81–1.81). Dose and duration of use did not affect the magnitude of the risk.

Conclusion

Domperidone use may increase the risk of VT/SCD in patients with PD, particularly those with a history of cardiovascular disease. This risk may be underestimated because of imprecision in identifying VT/SCD events.

Keywords: domperidone, Parkinson's disease, sudden cardiac death, ventricular arrhythmia

What is Already Known about this Subject

Results from a limited number of observational studies suggest an increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death associated with use of domperidone in the general population.

No study has assessed the risk in patients with Parkinson's disease. This is particularly relevant since patients with Parkinson's disease are preferentially treated with domperidone over other antiemetic agents to prevent digestive side‐effects of antiparkinsonian drugs.

What this Study Adds

In this multicentre retrospective cohort study using administrative databases from seven Canadian provinces and the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink, we found that domperidone use may increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in patients with Parkinson's disease, particularly those with a history of cardiovascular disease.

An excess risk might exist regardless of dose and duration of use.

Introduction

Domperidone is a peripheral dopamine D2 receptor antagonist with antiemetic and gastroprokinetic properties. It is approved in many countries for the treatment of nausea, vomiting and dyspepsia associated with motility disorders. In particular, domperidone is used for the symptomatic management of digestive symptoms associated with antiparkinsonian drugs. It can also help manage orthostatic hypotension induced by antiparkinsonian drugs.

The intravenous form of domperidone was withdrawn from the market worldwide in the 1980s following reports of serious cardiac events. Subsequently, concerns were raised regarding the oral form of domperidone based on reported cases of cardiotoxicity and in vitro studies demonstrating cardiac electrophysiological effects on the rapid component of the cardiac delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr), resulting in QT prolongation 1. Pharmacoepidemiologic studies in the general population suggesting an increased risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmia and sudden cardiac death (VT/SCD) prompted regulatory agencies to issue an advisory warning regarding its cardiac safety 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. New recommendations issued recently by health agencies in Europe and Canada include a maximum recommended daily dose of 30 mg, and contraindications such as underlying cardiac disease or concomitant QT‐prolonging drugs 7, 8. To date, no studies have assessed the risk of serious cardiac adverse events in patients with Parkinson's disease who are taking domperidone.

Cardiovascular disease and Parkinson's disease often coexist, with studies suggesting an association between Parkinson's disease and increased risk of acute myocardial infarction 9, impaired cardiac autonomic function, and a higher prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities 10. Heart failure is prevalent among patients with Parkinson's disease, estimated at 19% in one study, which may place this population at higher risk of VT/SCD when treated with medications that prolong the QT interval, such as domperidone 11. Moreover, incidence of Parkinson's disease increases sharply after age 60 12 and cardiac adverse events associated with domperidone may be greater in patients over 60 years old 3. Characterization of the risk in patients with Parkinson's disease is of crucial importance given that domperidone is preferentially prescribed over other antiemetic agents and is often the only therapeutic option to prevent digestive side‐effects of antiparkinsonian drugs because it does not readily cross the blood–brain barrier and does not worsen extrapyramidal symptoms in relation with Parkinson's disease. Our objective was therefore to assess the risk of VT/SCD associated with the use of domperidone in a population‐based cohort of patients with Parkinson's disease.

Methods

Study design and source population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a nested case–control analysis to assess the risk of VT/SCD associated with the use of domperidone compared with no use in a cohort of patients with Parkinson's disease using eight healthcare databases within the Canadian Network for Observational Drug Effect Studies (CNODES) 13. The provincial health administrative databases of the provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Québec and Saskatchewan, as well as the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) in the UK formed the source population. Of note, CNODES studies also include the CPRD as it provides rapid access to large and comprehensive data, including on drugs marketed in the UK before Canada 13. The results of these database‐specific analyses were pooled via meta‐analysis to obtain average treatment effects.

Ethics approval for each study was obtained from the respective academic institutions at all eight participating sites.

Cohort definition

The cohort included all patients in the databases aged 50 years or older (or 66 or older in Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia) with a first diagnosis of Parkinson's disease or a first prescription for an antiparkinsonian drug between 1 January 1990 (or one year after site‐specific data was available, whichever was later) and 30 June 2012.

Cohort patients were required to have contributed a minimum of 365 days of information in the database prior to cohort entry. To identify patients newly‐diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, we excluded those with a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease or who had been dispensed an antiparkinsonian drug in the year preceding cohort entry. Patients with a prescription for an antiparkinsonian drug without a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease but with another indication such as atypical parkinsonism or secondary parkinsonism, restless legs syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, or acromegaly in the year before cohort entry were not eligible for the study. We also excluded patients with a prescription for domperidone in the year before cohort entry as well as those with a history of ventricular tachyarrhythmia, aborted cardiac arrest, implantation of a cardiac defibrillator, cancer other than non‐melanoma skin cancer, or patients in a long‐term care facility in the year before cohort entry. All diagnoses, including PD, were identified using related International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 and 10 codes.

For all cohort members, cohort entry (time zero) was defined as the date of the first diagnosis of Parkinson's disease, or the date of the prescription for an antiparkinsonian drug, whichever came first within the study period. Follow‐up for all cohort members ended on the earliest of the following dates: the date of the outcome, the last date of data collection (end of coverage due to death or emigration from the province, entry in a long‐term care facility, transfer out of practice for CPRD database), or end of the study period (30 June 2012).

Case definition

The outcome consisted of a composite of VT or SCD. We identified all patients within our cohort with a first diagnosis of VT or SCD recorded at any time after cohort entry. The index date for each case was defined as the date of the first recorded VT or SCD. VT included ventricular tachycardia, fibrillation or flutter as identified by ICD 9 and 10 codes. SCD is classically defined as a sudden pulseless condition, whether immediately fatal or successfully resuscitated, that is consistent with a VT occurring in the absence of a known non‐cardiac condition as the proximate cause of death 14, 15. Accordingly, we aimed at identifying two types of out‐of‐hospital SCD cases: patients with a record of sudden death of presumed arrhythmic cardiac cause, and patients presumed to have died out of hospital from an arrhythmic cardiac event that was not necessarily labelled as sudden. VT and SCD occurring either in hospital or in long‐term care facilities were excluded as prescriptions issued in these settings were not available. However, patients who were admitted for VT or resuscitated from SCD in an emergency department, or who died shortly (<24 h) after their arrival to hospital were included. Deaths apparently due to non‐arrhythmic cardiac causes or to non‐cardiac pathology were excluded in order to capture events most likely to be compatible with the cardiac effects of domperidone.

In practice, the composite outcome was defined using a three‐step procedure performed independently in each province and centrally revised by the lead author (CR) as appropriate (Supplementary Figure S1): first, all potential cases were identified using relevant ICD 9 and 10 codes for VT, cardiac arrest and SCD (ICD 9 427.1, 427.4, V12.53, 427.5, 798.1, 798.2, 798.9, ICD 10 I47.0, I47.2, I49.0, Z86.74, I46.0, I46.1, I46.9, R96.0, R96.1, R98). All potential cases of SCD were linked to death certificates or vital statistics databases. Second, the complete profile of all potential VT, SCD as well as deaths not labelled as sudden occurring during follow‐up was subjected to a computer algorithm to identify and exclude events occurring either in hospital (after the first 24 h) or in long‐term care facilities, and deaths apparently due to non‐arrhythmic cardiac causes or life‐threatening non‐cardiac causes 9. To check and refine the accuracy of the computer algorithm, we initially reviewed the computerized medical records (CPRD) or administrative records (Manitoba and Ontario provincial databases) of a random sample of the potential cases of VT/SCD, blinded to the exposure status. Third, the computerized medical record (for CPRD) or the administrative record of all potential cases not excluded by the computer algorithm was manually reviewed in each centre to further exclude cases not meeting all inclusion and exclusion criteria, in particular to further exclude deaths apparently due to a non‐arrhythmic aetiology.

Control selection

For each case, up to 30 controls were randomly selected among the cohort members in the risk sets defined by the case, after matching on age (±1 year), sex, date of cohort entry (±1 year) and duration of follow‐up. If a case could not be matched to any control, the matching criteria were relaxed to age ± 2 years and cohort entry ±2 years. The index date for the controls was chosen in order for the controls to have the same duration of follow‐up as their matched cases. Matching on duration of follow‐up (i.e., our best estimate of duration of the disease) served as a proxy to control for potential confounding by progression and severity of Parkinson's disease. Because controls were selected from the risk set defined by each case, all controls were necessarily alive and event‐free when matched to their corresponding case. The same exclusion criteria used for cases applied to the eligible controls.

Definition of exposure

For all cases and their matched controls, we identified all prescriptions for domperidone during the year prior to the index date. Current exposure to domperidone was defined as a prescription dispensed (or written for CPRD) within 30 days before the index date. Recent use was defined as a prescription dispensed between 31 and 90 days before the index date, and past use as a prescription dispensed between 91 and 365 days before the index date. No use was defined as no prescription of domperidone in the year preceding the index date and was the reference category. Consequently, current, recent, past users and non‐users represented mutually exclusive exposure categories.

Covariates

Potential confounding variables included diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease, pacemaker or defibrillator), peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease (transient ischaemic attack and stroke), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, liver disease, other conditions that have been associated with an increased risk for sudden cardiac death (epilepsy, schizophrenia), cancer and measures of health utilization (number of hospitalizations and physician visits). All comorbidities were identified using related ICD 9 and 10 codes except for diabetes and hyperlipidaemia that were identified through diagnostic codes or use of antidiabetic and lipid‐lowering drugs, respectively. We also measured use of the following drugs: antihypertensive medications (beta‐blockers, thiazide diuretics, calcium‐channel blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers, and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor), anticoagulants, antiplatelets, antiparkinsonian drugs, drugs that could prolong the QT interval 16, and strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (as domperidone is mainly metabolized via the cytochrome p450 3A4 isoenzyme) 17. All covariates were measured in the year before the index date except QT‐prolonging drugs and strong inhibitors of CYP3A4, measured in the month preceding the index date.

Data analysis

Because of the time‐dependent nature of drug exposure and covariates, we used a nested case–control approach for the analysis 18, 19. Thus, conditional logistic regression was used to compute odds ratios that are unbiased estimators of incidence rate ratios (RRs), with little or no loss in precision. All analyses were performed independently at each site, which were kept blind to results from the other sites until the meta‐analysis was conducted.

In the primary analysis, RR of VT/SCD associated with current use of domperidone and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated from the odds ratios calculated using conditional logistic regression. By the matching process, all RR were inherently adjusted for sex, age, duration of follow‐up and calendar time. In addition, potential confounders described in the previous section were included in the multivariate analysis. In secondary analyses, we assessed the risk of VT/SCD in recent and past users as well as among current users according to duration of domperidone use (≤30 days, >30 days), and to the daily dose of domperidone (≤30 mg per day, >30 mg per day). To assess effect modification, we also conducted stratified analyses with respect to age (50–66, >66), pre‐existing vascular disease (cardiovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes), and concomitant use of QT‐prolonging drugs.

Sensitivity analyses

To explore the effect of potential misclassification of current exposure on the estimated RR, we changed the time window for current exposure to 60 days. We also repeated the primary analysis with covariates measured during two different time periods, to assess the potential adjustment for factors in the causal pathway between exposure and outcome. We first adjusted for confounding variables measured 366–730 days before the index date and then we adjusted only for covariates measured in the year prior to cohort entry. Finally, the primary analysis was repeated after excluding patients who spent more than 30 days in hospital in the 3 months prior to the index date, to evaluate the potential for immeasurable time bias 20. In a post‐hoc analysis, the primary analysis was performed after excluding SCD cases identified using the less specific ICD code 798.9 and R98, i.e., unattended death, to assess the impact of increasing the specificity of case definition.

Meta‐analysis

Inverse variance weighted RRs and 95% CIs were calculated to estimate the total effect across all study populations using fixed and random effects models.

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02500108.

Results

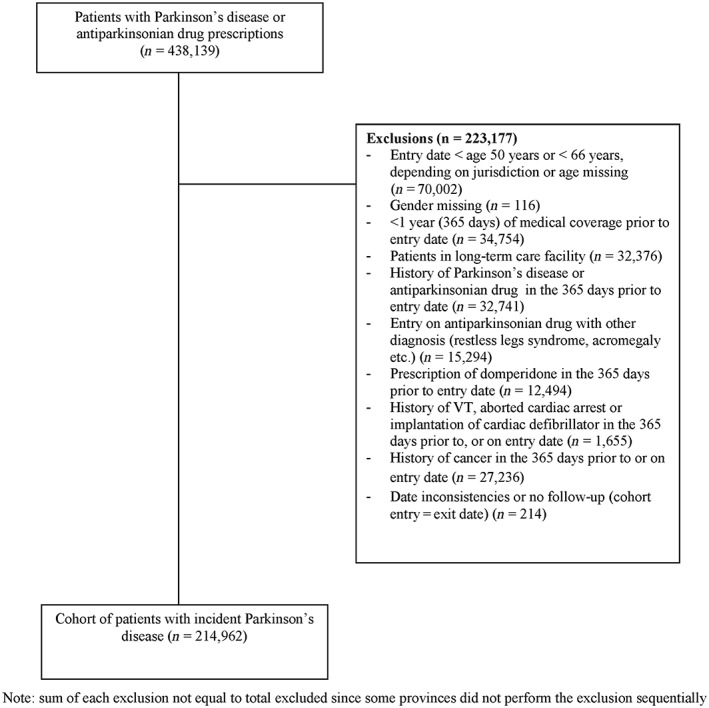

A total of 214 962 patients newly diagnosed with Parkinson's disease were identified across all sites after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). The mean age at cohort entry was 74.4 years and 52.6% were women. Among this cohort, 2907 cases of VT/SCD were identified during a total of 886 581 person‐years of follow‐up, yielding an incidence rate of 328 per 100 000 persons per year. The incidence rates varied across the databases from 192 per 100 000 persons per year in Saskatchewan, 246 in CPRD up to 534 in Québec and 901 in Nova Scotia. These variations in rates are likely related to the heterogeneity in the information available in databases, in particular details of hospitalizations and variation in death certificate reporting to vital statistics databases. Five cases could not be matched to any control and were therefore excluded from the analyses, leaving a total of 2902 cases matched to 81 347 controls. Characteristics of cases and their matched controls at index date are presented in Table 1. As expected, cases had a greater prevalence of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease than controls. They were also more likely to be treated with antithrombotic or antiarrhythmic drugs than their matched controls.

Figure 1.

Details of cohort definition

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases and controls*

| Cases (n = 2902) | Controls † (n = 81 347) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group at index date (n ,%) | ||||

| 50–59 | 64 | 2.2 | 1753 | 2.2 |

| 60–64 | 85 | 2.9 | 2298 | 2.8 |

| 65–69 | 170 | 5.9 | 5044 | 6.0 |

| 70–74 | 377 | 13.0 | 11 185 | 13.0 |

| 75–79 | 576 | 19.8 | 17 196 | 19.9 |

| 80+ | 1631 | 56.2 | 43 871 | 56.2 |

| Women (n, %) | 1335 | 46.0 | 37 555 | 46.0 |

| Measures of health utilization in the year prior to index date | ||||

| Number of hospitalizations | ||||

| 0 | 1282 | 44.2 | 55 866 | 68.7 |

| 1 | 812 | 28.0 | 15 879 | 19.5 |

| 2 | 412 | 14.2 | 6 060 | 7.5 |

| 3 or more | 396 | 13.6 | 3 542 | 4.3 |

| Number of physician visits | ||||

| ≤ 4 | 348 | 12.0 | 14 543 | 18.5 |

| > 4 | 2554 | 88.0 | 66 760 | 81.5 |

| Comorbidities defined in the year prior to index date (n ,%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 794 | 27.4 | 16 024 | 19.2 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 999 | 34.4 | 28 197 | 33.5 |

| Hypertension | 1271 | 43.8 | 31 462 | 38.5 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 1593 | 54.9 | 20 933 | 25.5 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 221 | 7.6 | 2916 | 3.6 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 251 | 8.6 | 4473 | 5.5 |

| COPD | 693 | 23.9 | 8878 | 10.9 |

| Renal failure | 511 | 17.6 | 5087 | 6.3 |

| Liver failure | 40 | 1.4 | 480 | 0.6 |

| Epilepsy | 91 | 3.1 | 1051 | 1.3 |

| Schizophrenia | 60 | 2.1 | 968 | 1.2 |

| Cancer | 239 | 8.2 | 4958 | 6.0 |

| Metabolic disorder associated with prolonged QT interval | 38 | 1.3 | 98 | 0.1 |

| Medication used in the year prior to index date (n ,%) | ||||

| Antiparkinsonian | 1511 | 52.1 | 40 509 | 49.1 |

| Levodopa | 1171 | 40.4 | 30 510 | 37.1 |

| Dopamine agonists | 369 | 12.7 | 11 233 | 13.6 |

| Rasagiline, selegiline | 62 | 2.1 | 1785 | 2.1 |

| Other | 194 | 6.7 | 4844 | 5.8 |

| Anticoagulant/Antiplatelet | 996 | 34.3 | 15 886 | 19.7 |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 2032 | 70.0 | 51 947 | 63.6 |

| Beta‐blockers | 1068 | 36.8 | 23 361 | 28.4 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 884 | 30.5 | 21 882 | 26.8 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs | 1429 | 49.2 | 34 423 | 41.9 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 324 | 11.2 | 10 440 | 12.7 |

| Drugs that could prolong QT interval (measured in the month prior index date) | 1448 | 49.9 | 27 495 | 33.5 |

| Strong inhibitors of CYP3A41 (measured in the month prior index date) | 58 | 2.0 | 657 | 0.8 |

Small cells (count ≤ 5) were suppressed by participating sites due to privacy restrictions. We assigned a value of 3 to these cells. For this reason, the sum of count data may differ slightly from the presented total.

The means and proportions among controls were weighted by the number of controls per case and then weighted by the number of cases per site.

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

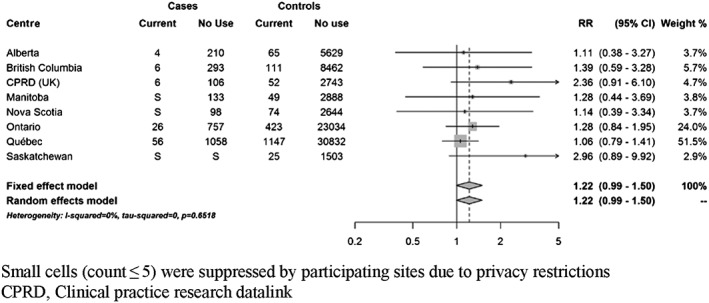

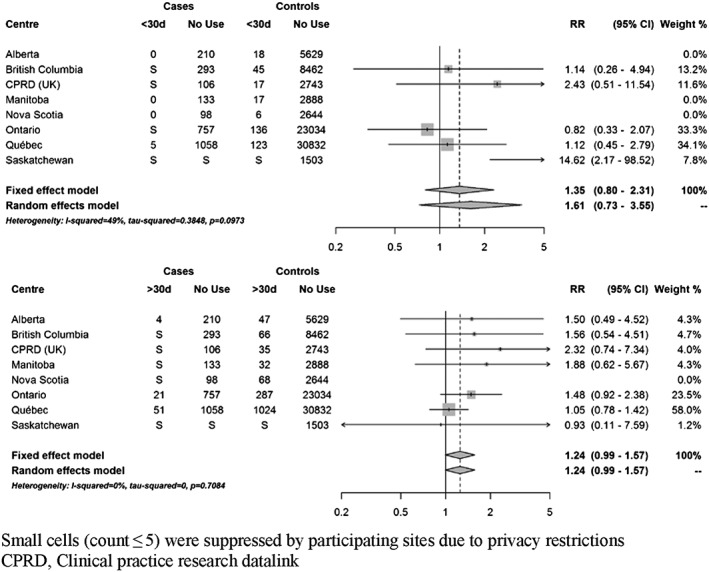

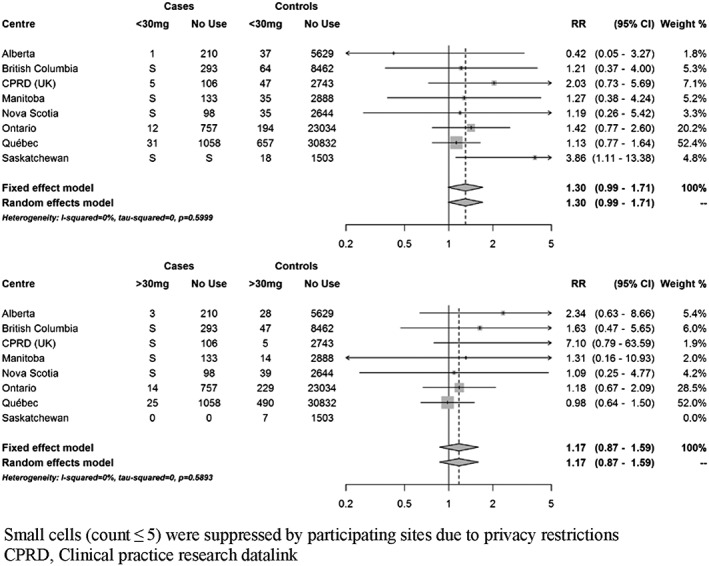

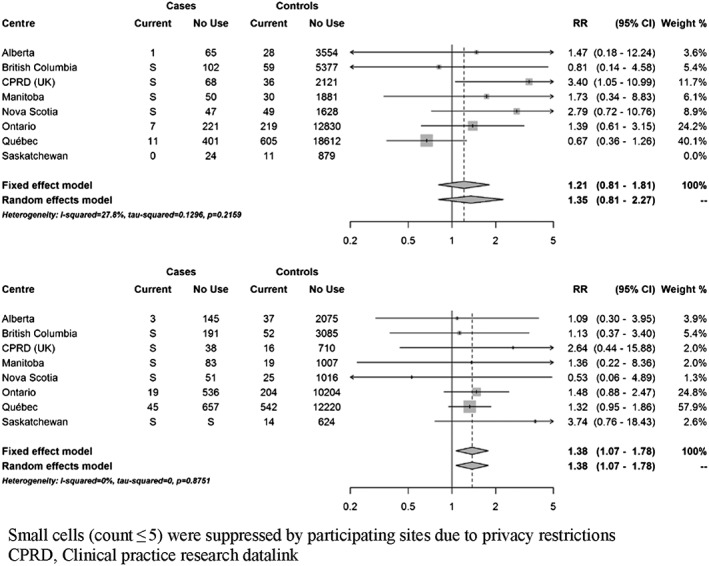

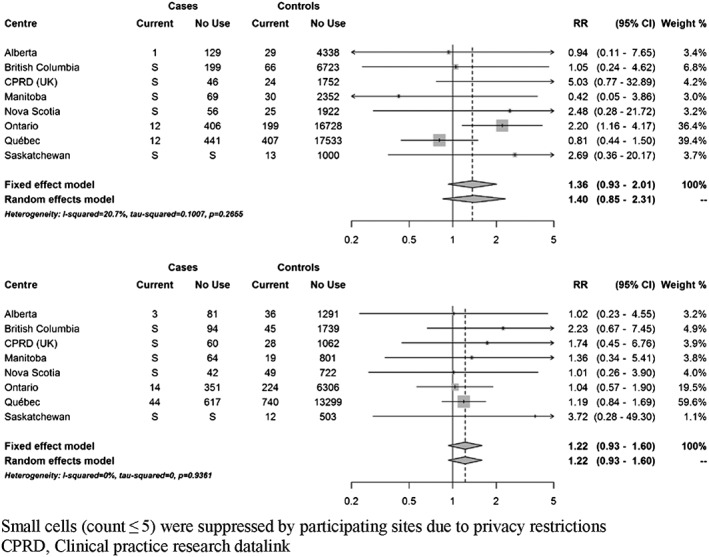

At index date, 111 cases (3.8%) were currently exposed to domperidone. Based on fixed‐effects meta‐analyses, current use of domperidone was associated with a 22% increased risk of VT/SCD nearly reaching statistical significance (RR 1.22; 95% CI 0.99–1.50) compared to non‐use (Figure 2). There was no clear trend towards an increased risk with recent or past use (Supplementary Figure S2). When current use was stratified by duration of use, short‐term use (less than 30 days) and more prolonged use were both associated with a non‐significant increased risk (35% and 24%, respectively) (Figure 3). Current use of 30 mg daily was associated with a non‐statistically significant increased risk of VT/SCD (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.99–1.71), whereas a more modest estimate was observed with higher daily dose (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.87–1.59) (Figure 4). The risk was greater in those with a history of vascular disease and statistically significant (RR 1.38; 95% CI 1.07–1.78) (Figure 5). There was also a trend towards an increased risk regardless of concomitant use of other QT‐prolonging drugs (Figure 6). The number of exposed cases in stratified analyses with respect to age was too small to allow for meaningful conclusions.

Figure 2.

Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use

Figure 3.

Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, stratified by duration of use. Use 30 days or less (top panel) and use for more than 30 days (bottom panel)

Figure 4.

Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, stratified by dose. Use of 30 mg or less (top panel). Use of more than 30 mg daily (bottom panel)

Figure 5.

Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, stratified by vascular disease. Among cases and controls without vascular disease (top panel) and with vascular disease (bottom panel)

Figure 6.

Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, stratified by concomitant use of QT prolonging drugs. Among cases and controls without concomitant QT drugs (top panel) and with concomitant QT drugs (bottom panel)

In sensitivity analyses, changing the definition of current exposure to domperidone to 60 days prior to the index date resulted, as expected, in a lower point estimate (RR 1.17; 95% CI 0.96–1.41) (Supplementary Figure S3). Repeating the primary analysis while adjusting for potential confounders measured 366–730 days before the index date or in the year before cohort entry yielded a higher excess risk, 34% and 43%, respectively, which was statistically significant (Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). Finally, when excluding patients with long hospital stay, the RR also reached statistical significance (RR 1.26 (1.03–1.56)) (Supplementary Figure S6). Restricting the analysis to more specific ICD codes of VT/SCD, the RR was 1.25 (95% CI 1.00–1.57) (Supplementary Figure S7).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first population‐based study to investigate whether domperidone use is associated with an increased risk of VT/SCD in patients with Parkinson's disease. The results of this study indicate that patients with Parkinson's disease currently using domperidone had a 22% increased risk of VT/SCD compared with non‐users although the estimate did not reach statistical significance. An excess risk might exist regardless of dose and duration of use. The risk was greater in those with a history of cardiovascular disease and statistically significant. The risk may also be increased in those without cardiovascular disease, however. Given the lack of traditional statistical significance in the Parkinson's population as a whole, an alternative explanation, although unlikely, is that there is no increase in risk of VT/SCD with domperidone in this population.

Several case–control studies have found that use of non‐cardiac QT‐prolonging drugs, including oral domperidone, increased the risk of sudden death in the general population; however, these studies were not designed to evaluate individual drugs 2, 4, 5. Two studies specifically assessed the risk of VT/SCD associated with oral domperidone in the general population 3, 6. The first study, a population‐based case–control study conducted in the Integrated Primary Care Information (ICPI) database in the Netherlands, comprised 1366 cases (62 VT and 1304 SCD) and 14 114 matched controls 6. Ten cases (all were SCD) were currently exposed to domperidone at index date. Current use of oral domperidone was associated with a non‐significant increased risk of SCD (OR 1.99; 95% CI 0.80–4.96), which was driven by an increased risk with daily doses greater than 30 mg (OR 11.4; 95% CI 1.99–65.2) but not with current use of 30 mg daily (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.23–4.42). These associations were based on only four cases exposed to domperidone 30 mg and four cases exposed to >30 mg. We were unable to show a difference in risk between doses less than 30 mg compared to doses of 30 mg or more. One explanation may be that misclassification of exposure is greater for patients exposed to higher doses, biasing point estimates downwards. Indeed, patients prescribed higher doses may be more likely to take less than the maximum prescribed dose or to be instructed to take up to maximum daily dose only if symptoms persist. On the other hand, our results indicate that the risk may exist even at small doses in patients with PD who represent a more vulnerable population than the general population.

The second study was a nested case–control study performed in the linked administrative databases of Saskatchewan Health 3. Among 1608 cases of VT/SCD, 169 were currently exposed to domperidone. Current use of oral domperidone was associated with an increased risk of VT/SCD compared with non‐use (OR 1.59; 95% CI 1.28–1.98). When stratified by age, the risk was increased in patients older than 60 years of age (OR 1.64; 95% CI 1.31–2.05) but not in younger patients (OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.35–3.47). The number of cases exposed in this stratified analysis was not reported. This study did not examine a dose‐effect relationship. Following these new findings and based on all available evidence, health regulating agencies issued further restrictions to the use of domperidone in the general population 7, 8. More recently, a case‐crossover study confirmed these findings in the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database although the authors reported an increased risk of VT/SCD also with doses of 30 mg or less (OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.36–1.67) 21.

Little is known about the effect of domperidone in patients with Parkinson's disease, although it is commonly used as an antiemetic agent to treat gastrointestinal symptoms caused by antiparkinsonian drugs. In a recent cross‐sectional study of 360 patients with Parkinson's disease in the UK, more than a third were taking QT‐prolonging medications and domperidone was the most frequently prescribed 22. Moreover, the prevalence of prolonged QT interval was higher in Parkinson's disease patients exposed to these drugs compared to those who were not 23. Recently, concerns were raised about use of domperidone in patients with Parkinson's disease as they may be particularly susceptible to developing QT prolongation and subsequent arrhythmias 24. Indeed, Parkinson's disease is associated with autonomic cardiac dysfunction which may in itself be a risk factor for QT prolongation 25. Moreover, Parkinson's disease occurs in the elderly with several associated comorbidities which may make them more prone to cardiac adverse events associated with domperidone use. Results of our pooled analysis suggest an increased risk in patients with PD, regardless of dose and duration of use.

Through the CNODES collaborative network, we were able to assemble a sufficiently large cohort of patients with Parkinson's disease to examine the risk associated with domperidone use. The selection of cases and controls was undertaken among this well‐defined cohort in each jurisdiction thus minimizing the potential for selection bias. Moreover, exposure to domperidone and all potential confounders were time‐dependent as a result of the risk‐set sampling scheme used for selection of controls. Finally, all data were collected prospectively, thereby eliminating the potential for recall bias, in particular regarding the exposure of interest. However, definition of exposure was based solely on prescriptions issued or filled and not on prescriptions actually taken by the patients. This could result in misclassification of exposure that is likely to be non‐differential between cases and controls, therefore potentially biasing the results towards the null. Also, given that the half‐life of domperidone is 7–9 h, an effect would not be expected more than a few days after the last pill was taken. As we were not able to precisely measure duration of use, we relied on prescriptions issued in the month before the index date to define current exposure. Consequently, some current users may actually have been unexposed which could again bias the results towards the null. Despite the potential for misclassification of exposure and underestimation of the magnitude of effect, we nevertheless observed an increased risk of VT/SCD.

Another potential threat to validity is the potential bias introduced by misclassification of the outcome as identifying SCD in databases may be challenging. A previous study has shown that identifying sudden cardiac death using an appropriate computer algorithm in administrative databases was feasible, with a positive predictive value of 86% in their sample, suggesting that the proportion of outcomes misclassified would be small 14. We used a three‐step procedure to identify all cases and this process included an algorithm followed by manual review of all available medical information for each potentially eligible case as previously done 26, resulting in a more accurate definition of SCD 27. Estimates across all databases were consistent towards an increased risk of VT/SCD with current use of domperidone except in the province of Québec where there was a null effect with current use and a trend towards an increased risk with past use. Consequently the effect of current use was diluted and the point estimate lower as Québec represented more than 50% of the weight in the pooled analysis. The numbers of cases selected based on the less specific code for SCD, i.e., unattended death, was surprisingly high in the Québec database, in contrast with other provinces which may be related to administrative determinants of coding of outpatient deaths. However, excluding risk‐sets with cases of unattended death only modestly increased the point estimate. Another explanation may be the lack of available information in the Québec database to correctly identify and exclude patients in long‐term care facilities or in hospital when we manually reviewed the potential cases. This hypothesis is corroborated by the higher rate of VT/SCD in Québec, reflecting the fact that we were not able to exclude as many potential cases as in other databases, thereby introducing misclassification of the outcome and immeasurable time bias 20 as exposure is not available for patients in hospital and long‐term care. Of note, this higher rate of VT/SCD in Québec is not explained by a higher exposure to domperidone in their cohort, which was 11% and very similar to other provinces.

Regarding potential residual confounding, which is always of concern in an observational study, we undertook several sensitivity analyses measuring covariates at different time points. Similar risks of VT/SCD were seen in all analyses.

In summary, domperidone use may increase the risk of VT/SCD in patients with Parkinson's disease, particularly those with a history of cardiovascular disease. This risk may be underestimated because of imprecision in identifying VT/SCD events. Therefore, physicians may reconsider using this drug unless the expected benefits clearly outweigh the excess cardiac risk.

Contributors

CR designed the study, interpreted data, and wrote and revised the manuscript. SD contributed to the study design and created a data analysis plan that was adapted for use in each jurisdiction and each dataset. All authors contributed to discussions on protocol development, participated in statistical analyses and interpretation of the data, and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. SD, PK, CM, SB and PE contributed to the definition of the outcome, in particular the testing of the algorithm. SD, PK and PE had an invaluable role in the interpretation of the data and revision of the first draft of the manuscript. The final manuscript was approved by the publications subcommittee of CNODES.

Funding

CNODES, a collaborating centre of the Drug Safety and Effectiveness Network (DSEN), is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant Number DSE‐111845).

Data Sharing

CNODES is not permitted to release individual level data or aggregated data with small cell sizes.

British Columbia data sources were as follows (http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data): British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2014): Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2014); British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2014): PharmaNet. V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2014); Canadian Institute for Health Information [creator] (2014): Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2014).British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2014): Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2014); BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator] (2014): Vital Statistics Deaths. V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. BC Vital Statistics Agency (2014).

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

We thank Matthew Dahl, Steve Doucette, Amélie Forget, Xinya Lu, Zhihai Ma, Richard Morrow, James Zhang, Yan Wang, and C. Fangyun Wu for their programming support. We also acknowledge the contributions of Corine Mizrahi and Melissa Dahan at the CNODES Coordinating Centre. We would like to acknowledge the important contributions of the CNODES collaborators and assistants at each site.

This study was made possible through data sharing agreements between CNODES member research centres and the respective provincial governments of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba (HIPC #2013/2014 – 43), Nova Scotia, Ontario, Québec and Saskatchewan. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors. No endorsement by the provinces is intended or should be inferred. This study was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC; protocol number 13_185R) of the CPRD; the approved protocol was made available to journal reviewers.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Case definition

Figure S2 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with recent use of (top panel) and past use (bottom panel) of domperidone compared to no use

Figure S3 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use. Exposure measured in the 60 days before index date

Figure S4 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, adjusting for covariates measured 366 to 730 days before index date

Figure S5 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, adjusting for covariates measured in the year before cohort entry

Figure S6 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use. Exclusion of patients with long hospital stay

Figure S7 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use. Exclusion of unattended death

Supporting info item

Renoux, C. , Dell'Aniello, S. , Khairy, P. , Marras, C. , Bugden, S. , Turin, T. C. , Blais, L. , Tamim, H. , Evans, C. , Steele, R. , Dormuth, C. , Ernst, P. , and the Canadian Network for Observational Drug Effect Studies (CNODES) investigators (2016) Ventricular tachyarrhythmia and sudden cardiac death with domperidone use in Parkinson's disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 82: 461–472. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12964.

References

- 1. Drolet B, Rousseau G, Daleau P, Cardinal R, Turgeon J. Domperidone should not be considered a no‐risk alternative to cisapride in the treatment of gastrointestinal motility disorders. Circulation 2000; 102: 1883–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Bruin ML, Langendijk PN, Koopmans RP, Wilde AA, Leufkens HG, Hoes AW. In‐hospital cardiac arrest is associated with use of non‐antiarrhythmic QTc‐prolonging drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 63: 216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johannes CB, Varas‐Lorenzo C, McQuay LJ, Midkiff KD, Fife D. Risk of serious ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in a cohort of users of domperidone: a nested case–control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010; 19: 881–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jolly K, Gammage MD, Cheng KK, Bradburn P, Banting MV, Langman MJ. Sudden death in patients receiving drugs tending to prolong the QT interval. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 68: 743–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Straus SM, Sturkenboom MC, Bleumink GS, Dieleman JP, van der Lei J, de Graeff PA, et al. Non‐cardiac QTc‐prolonging drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 2007–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Noord C, Dieleman JP, van Herpen G, Verhamme K, Sturkenboom MC. Domperidone and ventricular arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death: a population‐based case–control study in the Netherlands. Drug Saf 2010; 33: 1003–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. EMA . Restrictions on the use of domperidone‐containing medicines. European Medicines Agency, 1 September 2014. Report No.: EMA/465179/2014.

- 8. Government of Canada: Health Canada . Domperidone Maleate – Association with Serious Abnormal Heart Rhythms and Sudden Death (Cardiac Arrest) – For Health Professionals, 2015. [Online]. Available from: http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall‐alert‐rappel‐avis/hc‐sc/2015/43423a‐eng.php (last accessed 20 January 2015).

- 9. Liang HW, Huang YP, Pan SL. Parkinson disease and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a population‐based, propensity score‐matched, longitudinal follow‐up study. Am Heart J 2015; 169: 508–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kotagal V, Albin RL, Muller ML, Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Bohnen NI. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors and axial motor impairments in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2014; 82: 1514–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Renoux C, Dell'Aniello S, Brophy JM, Suissa S. Dopamine agonist use and the risk of heart failure. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012; 21: 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suissa S, Henry D, Caetano P, Dormuth CR, Ernst P, Hemmelgarn B, et al. CNODES: the Canadian Network for Observational Drug Effect Studies. Open Med 2012; 6: e134–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chung CP, Murray KT, Stein CM, Hall K, Ray WA. A computer case definition for sudden cardiac death. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010; 19: 563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siscovick DS, Raghunathan TE, Psaty BM, Koepsell TD, Wicklund KG, Lin X, et al. Diuretic therapy for hypertension and the risk of primary cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1852–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arizona Center for Education & Research on Therapeutics . Resources for professionals: QT drug lists by risk group, 2013. [Online]. Available at: http://www.azcert.org/medical‐pros/drug‐lists/drug‐lists.cfm (last accessed 7 December 2013).

- 17. US Food and Drug Administration . Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers. Table 5: Classification of In Vivo Inhibitors of CYP Enzymes (7/28/2011), 2011. [Online]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/DrugInteractionsLabeling/ucm093664.htm#classInhibit (last accessed 7 December 2013).

- 18. Essebag V, Genest J Jr, Suissa S, Pilote L. The nested case–control study in cardiology. Am Heart J 2003; 146: 581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Suissa S. Novel approaches to pharmacoepidemiology study design and statistical analysis In: Pharmacoepidemiology, 3rd edn, ed Strome BL. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000; 785–805. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suissa S. Immeasurable time bias in observational studies of drug effects on mortality. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168: 329–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen HL, Hsiao FY. Domperidone, cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme inhibitors and ventricular arrhythmia: a nationwide case‐crossover study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015; 24: 841–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malek NM, Grosset KA, Stewart D, Macphee GJ, Grosset DG. Prescription of drugs with potential adverse effects on cardiac conduction in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013; 19: 586–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cunnington AL, Hood K, White L. Outcomes of screening Parkinson's patients for QTc prolongation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013; 19: 1000–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lertxundi U, Domingo‐Echaburu S, Soraluce A, Garcia M, Ruiz‐Osante B, Aguirre C. Domperidone in Parkinson's disease: a perilous arrhythmogenic or the gold standard? Curr Drug Saf 2013; 8: 63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deguchi K, Sasaki I, Tsukaguchi M, Kamoda M, Touge T, Takeuchi H, et al. Abnormalities of rate‐corrected QT intervals in Parkinson's disease – a comparison with multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol Sci 2002; 199: 31–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martinez C, Assimes TL, Mines D, Dell'aniello S, Suissa S. Use of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants and the risk of sudden cardiac death or near death: a nested case–control study. BMJ 2010; 340: c249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chugh SS, Jui J, Gunson K, Stecker EC, John BT, Thompson B, et al. Current burden of sudden cardiac death: multiple source surveillance versus retrospective death certificate‐based review in a large US community. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44: 1268–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Case definition

Figure S2 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with recent use of (top panel) and past use (bottom panel) of domperidone compared to no use

Figure S3 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use. Exposure measured in the 60 days before index date

Figure S4 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, adjusting for covariates measured 366 to 730 days before index date

Figure S5 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use, adjusting for covariates measured in the year before cohort entry

Figure S6 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use. Exclusion of patients with long hospital stay

Figure S7 Adjusted rate ratios of ventricular tachyarrhythmia/sudden cardiac death associated with current use of domperidone compared to no use. Exclusion of unattended death

Supporting info item