Abstract

Background

African trypanosomes are the causative agents of sleeping sickness in humans and nagana disease in livestock animals. As the few drugs available for treatment of the diseases have limited efficacy and produce adverse reactions, new and better tolerated therapies are required. Polyether ionophores have been shown to display anti-cancer, anti-microbial and anti-parasitic activity. In this study, derivatives of the polyether ionophores, salinomycin and monensin were tested for their in vitro activity against bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei and human HL-60 cells.

Results

Most polyether ionophore derivatives were less trypanocidal than their corresponding parent compounds. However, two salinomycin derivatives (salinomycin n-butyl amide and salinomycin 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl ester) were identified that showed increased anti-trypanosomal activity with 50 % growth inhibition values in the mid nanomolar range and minimum inhibitory concentrations of below 1 μM similar to suramin, a drug used in the treatment of sleeping sickness. In contrast, human HL-60 cells were considerably less sensitive towards all polyether ionophore derivatives. The cytotoxic to trypanocidal activity ratio (selectivity) of the two promising compounds was greater than 250.

Conclusions

The data indicate that polyether ionophore derivatives are interesting lead compounds for rational anti-trypanosomal drug development.

Keywords: Trypanosoma brucei, Salinomycin derivatives, Monensin derivatives, African trypanosomaisis, Drug screening

Background

African trypanosomiasis is an infectious parasitic disease of humans and animals of similar aetiology and epidemiology. The causative agents of the disease are flagellated protozoans of the genus Trypanosoma. The parasites are transmitted by the bite of infected tsetse flies (Glossina sp.) and live and multiply in the blood and tissue fluids of their mammalian host. The distribution of trypanosomiasis in Africa corresponds to the range of tsetse flies and comprises an area of 8 million km2 between 14°N and 20°S latitude [1]. In this so-called tsetse belt, millions of people and cattle are at risk of contracting the disease [2, 3]. Throughout history, African trypanosomiasis has severely repressed the economic and cultural development of central Africa [4].

For treatment of African trypanosomiasis only a handful drugs are available. All the drugs are outdated, require parenteral administration, induce significant toxic side effects, have limited efficacy and are being increasingly subject to drug resistance [5–7]. Thus, there is an urgent need for the development of new, more effective and safer treatments for African trypanosomiasis.

In recent years, polyether ionophores have received attention as promising anti-cancer candidate drugs [8]. However, compounds displaying anti-cancer activity often also exhibit trypanocidal activity [9]. Recently it has been shown that the ionophore salinomycin inhibits the growth of bloodstream forms of T. brucei in vitro at sub-micromolar concentration [10]. Although salinomycin was shown to be less toxic to human cells, its selectivity (cytotoxic/trypanocidal ratio) was in a moderate range (< 100) [10]. Therefore, we were interested whether chemical modification of polyether ionophores, such as salinomycin and monensin, could lead to compounds with improved trypanocidal activity and better selectivity.

Methods

Compounds

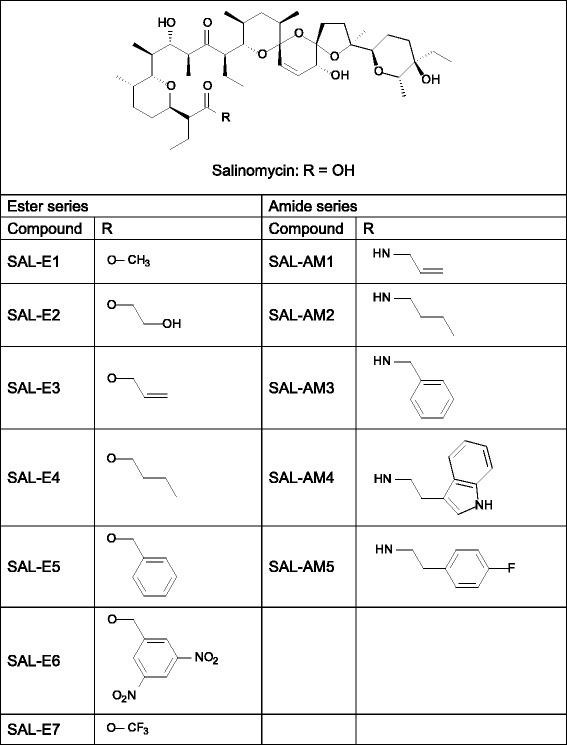

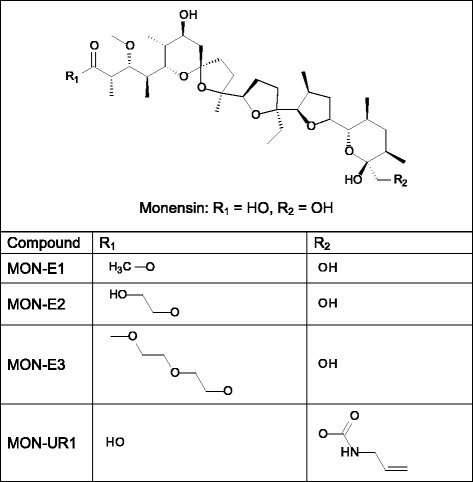

The synthesis of the twelve salinomycin derivatives (Fig. 1) and the four monensin derivatives (Fig. 2) investigated in this study is described elsewhere [11–17].

Fig. 1.

Structure of salinomycin and its derivatives studied in this work

Fig. 2.

Structure of monensin and its derivatives studied in this work

Cell cultures

Bloodstream forms of T. brucei (clone 427-221a) [18] and human myeloid leukaemia HL-60 cells [19] were grown in Baltz medium [20] and RPMI medium [21], respectively. Both culture media were supplemented with 16.7 % (v/v) heat-inactivated foetal calf serum. All cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2 at 37 °C.

Toxicity assays

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates in a final volume of 200 μl of their respective culture medium containing 10-fold serial dilutions of ionophore derivatives (10-4 to 10-10 M) and 1 % DMSO. Wells containing medium and 1 % DMSO served as controls. The initial cell densities were 1 × 104/ml for T. brucei and 1 × 105/ml for HL-60 cells. After 24 h incubation at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5 % CO2, 20 μl of a 0.44 mM resazurin solution prepared in PBS was added and the cells were incubated for a further 48 h so that the total incubation time was 72 h. Thereafter, the plates were read on a microplate reader using a test wavelength of 570 nm and a reference wavelength of 630 nm. The 50 % growth inhibition (GI50) value, i.e. the concentration of a compound necessary to reduce the growth rate of cells by 50 % compared to the control was determined by linear interpolation according to the method described in [22]. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, i.e. the concentration of the drug at which all trypanosome and human cells were killed, was determined microscopically. Each compound was independently tested three times.

Measurement of changes in cell volume

Change in cell volume was determined by light scattering as previously described [10]. In brief, bloodstream forms of T. brucei were seeded at a density of 5 × 107 cells/ml in 96-well plates in a final volume of 200 μl culture medium containing 100 μM of salinomycin or the salonimycin derivatives SAL-E7 or SAL-AM2 and 1 % DMSO. Absorbance of the cultures was measured at 490 nm every 15 min. A decrease in absorbance corresponded to an increase in cell volume. The experiment was repeated three times.

Results and discussion

It has been shown that chemical modification of polyether ionophore not only can increase their anti-cancer and anti-bacterial activity but also can reduce their general cytotoxicity [23]. In addition, salinomycin and monensin with modified carboxyl groups (esters or amides) transport cations via an electrogenic or biomimetic mechanism while the unmodified parent ionophores carry cations across membranes always by an electroneutral mechanism [6]. This change in ionophoretic properties can lead to compounds with better biological activities. Most salinomycin and all monensin derivatives tested in this study were found to be less trypanocidal than their parent compounds with MIC values of 10 μM and GI50 values of around 3 μM (Table 1). Only the salinomycin derivatives SAL-E7 (2,2,2-trifluoroethyl ester) and SAL-AM2 (n-butyl amide) displayed increased trypanocidal activity with MIC values ranging between 0.1–1 μM and GI50 values in the mid nanomolar range (Table 1). Notably, both compounds exhibited similar trypanocidal activity to suramin (MIC = 0.1 μM; GI50 = 0.035 ± 0.002 μM) (Table 1), one of the drugs used in the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis or sleeping sickness. However, no obvious structure-activity relationship trend could be detected. For example, while the n-butyl amide derivative SAL-AM2 was 4.5 times more trypanocidal than salinomycin, the corresponding n-butyl ester derivative SAL-E4 was 17 times less trypanocidal than its parent compound (Table 1).

Table 1.

GI50 and MIC values and ratios of salinomycin and monensin derivatives for T. brucei and HL-60 cells

| T. brucei | HL-60 | Selectivity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | MIC (μM)a | GI50 (μM)b | MIC (μM)a | GI50 (μM)b | MIC ratioc | GI50 ratiod |

| Salinomycin | 1 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 1 | 0.44 ± 0.21 | 1 | 2.4 |

| SAL-E1 | 10 | 3.08 ± 0.18 | 100 | 35.5 ± 2.4 | 10 | 11.4 |

| SAL-E2 | 10 | 3.25 ± 0.26 | 100 | 34.6 ± 1.9 | 10 | 10.6 |

| SAL-E3 | 10 | 3.10 ± 0.21 | 100 | 33.8 ± 3.5 | 10 | 10.9 |

| SAL-E4 | 10 | 3.12 ± 0.08 | 100 | 32.9 ± 2.5 | 10 | 10.5 |

| SAL-E5 | 10 | 3.21 ± 0.02 | 100 | 38.4 ± 4.2 | 10 | 11.0 |

| SAL-E6 | 10 | 3.01 ± 0.06 | > 100 | > 100 | > 10 | > 33 |

| SAL-E7 | 0.1–1e | 0.057 ± 0.029 | 100 | 16.4 ± 1.9 | 100–1000 | 288 |

| SAL-AM1 | 10 | 3.23 ± 0.21 | 100 | 38.9 ± 3.2 | 10 | 12.0 |

| SAL-AM2 | 0.1 | 0.040 ± 0.007 | 100 | 14.5 ± 1.3 | 1000 | 363 |

| SAL-AM3 | 10 | 2.94 ± 0.20 | 100 | 7.92 ± 1.95 | 10 | 2.7 |

| SAL-AM4 | 10 | 2.69 ± 0.51 | 100 | 24.5 ± 3.7 | 10 | 9.1 |

| SAL-AM5 | 10 | 2.69 ± 0.20 | 100 | 39.2 ± 1.6 | 10 | 14.6 |

| Monensin | 0.1 | 0.029 ± 0.002 | 10 | 1.48 ± 0.56 | 100 | 51 |

| MON-E1 | 10 | 3.06 ± 0.06 | 100 | 34.1 ± 2.2 | 10 | 11.1 |

| MON-E2 | 10 | 2.76 ± 0.10 | 100 | 25.3 ± 5.0 | 10 | 9.2 |

| MON-E3 | 10 | 1.68 ± 0.56 | 100 | 20.3 ± 3.1 | 10 | 12.1 |

| MON-UR1 | 1 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 100 | 23.3 ± 6.6 | 100 | 75 |

| Suraminf | 0.1 | 0.035 ± 0.002 | > 100 | > 100 | > 1000 | > 2857 |

aData shown are mean values of three independent experiments

bData shown are mean values ± SD of three independent experiments

cMIC ratio, MIC(HL-60)/MIC(T. brucei)

dGI50 ratio, GI50(HL-60)/GI50(T. brucei)

eAfter an incubation period of 72 h, in one of the three experiments a few motile trypanosomes were observed at a concentration of 0.1 μM (but none at 1 μM) while in the two other experiments no motile parasites were found at that concentration. Thus, a range of 0.1–1 μM as MIC value was assigned

fReference control

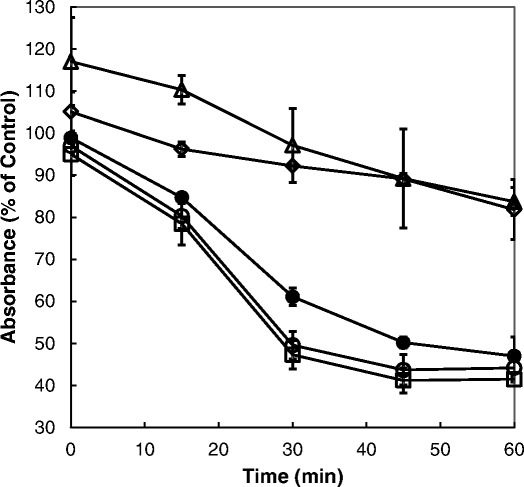

The lack of any clear structure-activity relationship for salinomycin derivatives raised the question whether the two most active substances SAL-E7 and SAL-AM2 share the same mechanism of action as their parent compound. Previously it was shown that the trypanocidal action of salinomycin was due to an influx of Na+-ions which subsequently induced swelling of the cells [10]. Change in cell volume can be measured by light scattering at 450–550 nm whereby a decrease in absorbance indicates swelling of cells. In order to be able to record measurable absorbance changes, a high cell density is required. However, since trypanosomes do not survive for a very long time at high cell density in culture, a much higher concentration of ionophores was needed (100 μM) in order to produce fast enough cell swelling [10]. Incubation of trypanosomes with SAL-E7 or SAL-AM2 resulted in cell swelling similar to parasites treated with salinomycin (Fig. 3). However, the derivatives caused a slightly faster swelling of the cells than salinomyicn. After 45 min incubation no further decrease in absorbance was recorded indicating that the endpoint of the swelling process induced by the derivatives was reached. Trypanosomes treated with the parent compound salinomycin continued to swell until the end of experiment. In contrast, when trypanosomes were incubated with derivatives that were found to be less trypanocidal, a prompt increase in absorbance was observed indicating an instantaneous shrinking of the cells (Fig. 3 and data not shown). During further incubation, trypanosomes increased their cell volume but cell swelling was much slower and much less. These results indicate that salinomycin derivatives with modified carboxyl group retain ionophoretic activity but depending on the modification they may transport cations more or less efficient across membranes. However, it seems that the transport efficiency determines the trypanocidal potency of salinomycin derivatives.

Fig. 3.

Effect of salinomycin derivatives on the cell volume of bloodstream forms of T. brucei. Trypanosomes (5 × 107 cell/ml) were incubated with 100 μM salinomycin (closed circles), SAL-E7 (open circles), SAL-AM2 (open squares), SAL-E4 (open triangles), or SAL-AM1 (open diamonds) in culture medium. Every 15 min, the absorbance at 490 nm was measured. Mean values ± SD of three experiments are shown. At the time points 30 and 45 min, the values for SAL-E7 and SAL-AM2 were statistically significantly different from the values for salinomycin (P < 0.05). At the time points 15, 30, 45 and 60 min, the values for SAL-E4 and SAL-AM1 were statistically significantly different from the values for salinomycin (P < 0.05). Note that a decrease in absorbance corresponds to an increase in cell volume

For determination of the general cytotoxicity of salinomycin and monensin derivatives, HL-60 cells were used as reference because their sensitivity for approved trypanocides is well established [24, 25]. All derivatives were less cytotoxic towards HL-60 cells than their parent compounds with MIC values of 100 μM and GI50 values ranging between 7.9–39 μM (Table 1). Compound SAL-E6 did not affect HL-60 cells, even at 100 μM, indicating that salinomycin 2,4-dinitrobenzyl ester displays no cytotoxicity (Table 1). Overall, the observed cytotoxic activities of the salinomycin derivatives were in good agreement with previously reported findings [11–13].

With the exception of SAL-AM3 (benzyl amide), the selectivity indices (MIC and GI50 ratios) of salinomycin derivatives were found to be better than those of the parent compound salinomycin. Most derivatives had selectivity indices of around 10 (Table 1). Compounds SAL-E7 and SAL-AM2 had promising MIC and GI50 ratios of > 100 (Table 1). In contrast to salinomycin derivatives, the selectivity indices of most monensin derivatives were found to be inferior to the parent compound monensin (Table 1). Only MON-UR1 (alkyl urethane) had MIC and GI50 ratios similar to those of monensin (Table 1). By comparison, drugs used for treatment of African trypanosomiasis have much higher selectivity indices [24, 25]. For example, the reference drug suramin displayed no toxicity towards HL-60 cells with MIC and GI50 values greater than 100 μM. Accordingly, the MIC and GI50 ratios for suramin were > 1000 and > 2857, respectively (Table 1).

This study has shown that the polyether ionophores can be modified into derivatives with improved trypanocidal and reduced cytotoxic activity. Two salinomycin derivatives, SAL-E7 and Sal-AM2, were identified that, in this respect, were superior to the parent compound. In contrast to salinomycin, derivatization of monensin did not result in compounds with increased trypanocidal activity. One reason for this maybe that monensin itself is already quite trypanocidal (about 6–10 times more active than salinomycin) and, therefore, it might be difficult to improve its trypanocidal activity further by chemical modification.

Conclusion

Both, SAL-E7 and SAL-AM2, match the activity criteria for drug candidates for African trypanosomiasis (GI50 < 1 μM; selectivity > 100) [26]. However, it should be noted that in this study a cancer cell line was used for determining selectivity and that, compared with non-malignant cells, cytotoxicity of both compounds are therefore likely to be overestimated as has been shown for the parent compound salinomycin. For example, the cytotoxicity of salinomyicn in human peripheral blood mononuclear and nasal mucosa cells was determined to be in the mid-micromolar range with 50 % effective concentrations of 30 and 11 μM, respectively [10, 27]. Before developing any salinomycin derivatives into trypanocides, animal experiments should be carried out to establish the in vivo activity of the compounds.

Abbreviations

DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; GI50, 50 % growth inhibition; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The work received financial support from the Polish National Science Centre (NCN) [2011/03/D/ST5/05884]. MA wishes to thank the Polish National Science Centre (NCN) for the doctoral scholarship “ETIUDA” [2014/12/T/ST5/00710] and the Adam Mickiewicz University Foundation for a scholarship granted in 2015/2016.

Availability of data and materials

All data are disclosed as tables and figures in the main document.

Authors’ contribution

DS and AH conceived and designed the study. MA and AH carried out the synthesis of compounds. DS performed the in vitro toxicity assays. DS and AH analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Dietmar Steverding, Email: dsteverding@hotmail.com.

Michał Antoszczak, Email: michant@amu.edu.pl.

Adam Huczyński, Email: adhucz@amu.edu.pl.

References

- 1.Molyneux DH, Pentreath V, Doua F. African trypanosomiasis in man. In: Cook GC, editor. Manson’s Tropical Diseases. 20. London: Saunders; 1996. pp. 1171–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness). World Health Org Fact Sheet. 2016;259. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs259/en/. Accessed 4 May 2016.

- 3.World Health Organization. Control of human African trypanosomiasis: a strategy for the African region. AFR/RC55/11. 2005. http://www.who.int/trypanosomiasis_african/resources/afro_tryps_strategy.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2016.

- 4.Steverding D. The history of African trypanosomiasis. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Fairlamb AH. Chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis: current and future prospects. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:488–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matovu E, Seebeck T, Enyaru JC, Kaminsky R. Drug resistance in Trypanosoma brucei ssp., the causative agents of sleeping sickness in man and nagana in cattle. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:763–70. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delespaux V, de Koning HP. Drugs and drug resistance in African trypanosomiasis. Drug Resist Updat. 2007;10:30–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huczyński A. Polyether ionophores – promising bioactive molecules for cancer therapy. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:7002–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett SV, Barrett MP. Anti-sleeping sickness drugs and cancer chemotherapy. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:7–9. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(99)01560-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steverding D, Sexton DW. Trypanocidal activity of salinomycin is due to sodium influx followed by cell swelling. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:78. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Stefańska J, Antoszczak M, Brzezinski B. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of amide derivatives of polyether antibiotic-salinomycin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:4697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antoszczak M, Maj E, Stefańska J, Wietrzyk J, Janczak J, Brzezinski B, Huczyński A. Synthesis, antiproliferative and antibacterial activity of new amides of salinomycin. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:1724–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoszczak M, Popiel K, Stefańska J, Wietrzyk J, Maj E, Janczak J, Michalska G, Brzezinski B, Huczyński A. Synthesis, cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity of new esters of polyether antibiotic - salinomycin. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;76:435–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huczyński A, Przybylski P, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. Monensin A methyl ester complexes with Li+, Na+, and K+ cations studied by ESI-MS, 1H- and 13C-NMR, FTIR, as well as PM5 semiempirical method. Biopolymers. 2006;81:282–94. doi: 10.1002/bip.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huczyński A, Przybylski P, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. Spectroscopic, mass spectrometry, and semiempirical investigation of a new ester of Monensin A with ethylene glycol and its complexes with monovalent metal cations. Biopolymers. 2006;82:491–503. doi: 10.1002/bip.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huczyński A, Stefańska J, Przybylski P, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of monensin A esters. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:2585–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huczyński A, Janczak J, Brzezinski B, Bartl F. Spectroscopic and structural studies of allyl urethane derivative of Monensin A sodium salt. J Mol Struct. 2013;1043:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirumi H, Hirumi K, Doyle JJ, Gross GAM. In vitro cloning of animal infective bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitology. 1980;80:371–82. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins SJ, Gallo RC, Gallagher RE. Continues growth and differentiation of human myeloid leukaemic cells in suspension cultures. Nature. 1977;270:347–9. doi: 10.1038/270347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baltz T, Baltz D, Giroud C, Crockett L. Cultivation in a semi-defined medium of animal infective forms of Trypanosoma brucei, T. equiperdum, T. evansi, T. rhodesiense and T. gambiense. EMBO J. 1985;4:1273–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore GE, Gerner RE, Franklin HA. Culture of normal human leukocytes. J Am Med Assoc. 1967;199:519–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.1967.03120080053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber W, Koella JC. A comparison of three methods of estimating EC50 in studies of drug resistance of malaria parasites. Acta Trop. 1993;55:257–61. doi: 10.1016/0001-706X(93)90083-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antoszczak M, Rutkowski J, Huczyński A. Structure and biological activity of polyether ionophores and their semi-synthetic derivatives. In: Brahmachari G, editor. Bioactive Natural Products: Chemistry and Biology. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag; 2015. p. 107–170.

- 24.Merschjohann K, Sporer F, Steverding D, Wink M. In vitro effect of alkaloids on bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei and T. congolense. Planta Med. 2001;67:623–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caffrey CR, Steverding D, Swenerton RK, Kelly B, Walshe D, Debnath A, et al. Bis-acridines as lead antiparasitic agents: structure-activity analysis of a discrete compound library in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2164–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Nwaka S, Hudson A. Innovative lead discovery strategies for tropical diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:941–55. doi: 10.1038/nrd2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherzad A, Hackenberg S, Schramm C, Froelich K, Ginzkey C, Hager R, et al. Geno- and cytotoxicity of salinomycin in human nasal mucosa and peripheral blood lymphocytes. Toxicol In Vitro. 2015;29:813–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are disclosed as tables and figures in the main document.