Variability in Rubisco kinetic parameters and their temperature dependency demonstrate differences in photosynthetic efficiency in the most important crops worldwide.

Abstract

Rubisco catalytic traits and their thermal dependence are two major factors limiting the CO2 assimilation potential of plants. In this study, we present the profile of Rubisco kinetics for 20 crop species at three different temperatures. The results largely confirmed the existence of significant variation in the Rubisco kinetics among species. Although some of the species tended to present Rubisco with higher thermal sensitivity (e.g. Oryza sativa) than others (e.g. Lactuca sativa), interspecific differences depended on the kinetic parameter. Comparing the temperature response of the different kinetic parameters, the Rubisco Km for CO2 presented higher energy of activation than the maximum carboxylation rate and the CO2 compensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration. The analysis of the Rubisco large subunit sequence revealed the existence of some sites under adaptive evolution in branches with specific kinetic traits. Because Rubisco kinetics and their temperature dependency were species specific, they largely affected the assimilation potential of Rubisco from the different crops, especially under those conditions (i.e. low CO2 availability at the site of carboxylation and high temperature) inducing Rubisco-limited photosynthesis. As an example, at 25°C, Rubisco from Hordeum vulgare and Glycine max presented, respectively, the highest and lowest potential for CO2 assimilation at both high and low chloroplastic CO2 concentrations. In our opinion, this information is relevant to improve photosynthesis models and should be considered in future attempts to design more efficient Rubiscos.

The reported stagnation in the annual gains of cereal yields in the last decade clearly indicates that the expected demand for increased yield, at least 50% by 2050 (http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-home/en/), will not be met by conventional breeding (Zhu et al., 2010). Future improvements will come from novel bioengineering approaches specifically focused on processes limiting crop productivity that have not been addressed so far (Parry and Hawkesford, 2012; Ort et al., 2015). A number of specific modifications to the primary processes of photosynthesis that could increase canopy carbon assimilation and production through step changes include the modification of the catalytic properties of Rubisco (Murchie et al., 2009; Whitney et al., 2011; Parry et al., 2013; Ort et al., 2015). First, biochemical models indicate that CO2 fixation rates are limited by Rubisco activity under physiologically relevant conditions (Farquhar et al., 1980; von Caemmerer, 2000; Rogers, 2014). Second, Rubisco’s catalytic mechanism exhibits important inefficiencies that compromise photosynthetic productivity: it is a slow catalyst, forcing plants to accumulate large amounts of the protein, and unable to distinguish between CO2 and oxygen, starting a wasteful side reaction with oxygen that leads to the release of previously fixed CO2, NH2, and energy (Roy and Andrews, 2000). These inefficiencies limit not only the rate of CO2 fixation but also the capacity of crops for an optimal use of resources, principally water and nitrogen (Flexas et al., 2010; Parry and Hawkesford, 2012).

Rubisco kinetic parameters has been described in vitro at 25°C for about 250 species of higher plants, of which only approximately 8% are crop species (Yeoh et al., 1981; Bird et al., 1982; Sage, 2002; Ishikawa et al., 2009; Prins et al., 2016). These data revealed the existence of significant variability in the main Rubisco kinetic parameters both among C3 species (Yeoh et al., 1980, 1981; Bird et al., 1982; Jordan and Ogren, 1983; Parry et al., 1987; Castrillo, 1995; Delgado et al., 1995; Kent and Tomany, 1995; Balaguer et al., 1996; Bota et al., 2002; Galmés et al., 2005, 2014a, 2014c; Ghannoum et al., 2005; Ishikawa et al., 2009) and between C3 and C4 species (Kane et al., 1994; Sage, 2002; Kubien et al., 2008; Perdomo et al., 2015b). The existence of Rubiscos with different catalytic traits implies that the success, in terms of photosynthetic improvement, of Rubisco engineering approaches in crops will depend on the specific performance of the native enzyme from each crop species. Nevertheless, our knowledge of the actual variability in Rubisco kinetics is still narrow, not only because of the limited number of species that have been examined so far but mainly because complete Rubisco kinetic characterization (including the main parameters) has been performed in very few species.

Recent modeling confirmed that Rubisco is not perfectly optimized to deliver maximum rates of photosynthesis and indicated that Rubisco optimization depends on the environmental conditions under which the enzyme operates (Galmés et al., 2014b). In particular, Rubisco catalytic parameters are highly sensitive to changes in temperature. For instance, the maximum carboxylase turnover rate (kcatc) increases exponentially with temperature (Sage, 2002; Galmés et al., 2015). However, at temperatures higher than the photosynthetic thermal optimum, the increases in kcatc are not translated into increased CO2 assimilation because of the decreased affinity of Rubisco for CO2 (i.e. higher Michaelis-Menten constant for CO2 [Kc] and lower CO2-oxygen specificity [Sc/o]) and the decreased CO2-oxygen concentration ratio in solution (Hall and Keys, 1983; Jordan and Ogren, 1984). These changes favor the ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) oxygenation by Rubisco relative to carboxylation, increasing the flux through photorespiration and, ultimately, reducing the potential growth at high temperatures (Jordan and Ogren, 1984).

Beyond the discernment of the existing variability in Rubisco kinetics at a standard temperature, the knowledge of the temperature dependence of Rubisco kinetics and the existence of variability in the thermal sensitivity among higher plants are of key importance for modeling purposes. The number and diversity of plant species for which Rubisco kinetic parameters have been tested in vitro at a range of physiologically relevant temperatures are still very scarce (Laing et al., 1974; Badger and Collatz, 1977; Badger, 1980; Monson et al., 1982; Hall and Keys, 1983; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Lehnherr et al., 1985; Uemura et al., 1997; Zhu et al., 1998; Sage et al., 2002; Galmés et al., 2005; Haslam et al., 2005; Yamori et al., 2006; Perdomo et al., 2015a; Prins et al., 2016) and mostly restricted to a few kinetic parameters; actually, there is no study examining the temperature dependencies of the main kinetic constants in the same species. The limited data reported so far suggest the existence of interspecific differences in the temperature dependence of some Rubisco kinetic parameters, like kcatc (Chabot et al., 1972; Weber et al., 1977; Sage, 2002) or Sc/o (Zhu et al., 1998; Galmés et al., 2005). Actually, differences in the energy of activation of kcatc and Sc/o seem to be ascribed to the thermal conditions typically encountered by the species in their native habitat (Galmés et al., 2005) as well as to the photosynthetic mechanism (Perdomo et al., 2015a).

The variability in the response of Rubisco kinetics to changes in temperature, if confirmed, is of paramount importance. The mechanistic models of photosynthesis at leaf, canopy, and ecosystem levels are based on the kinetic properties of Rubisco (Farquhar et al., 1980; von Caemmerer, 2000; Bernacchi et al., 2002), and the accuracy of these photosynthetic models depends on knowing the Rubisco kinetic parameters and the species-specific equations for the Rubisco-temperature dependencies (Niinemets et al., 2009; Yamori and von Caemmerer, 2009; Bermúdez et al., 2012; Díaz-Espejo, 2013; von Caemmerer, 2013; Walker et al., 2013). The need for estimations of the temperature dependencies of Rubisco kinetic parameters becomes timely as modelers try to predict the impact of increasing temperatures on global plant productivity (Sage et al., 2008; Gornall et al., 2010). Ideally, surveying variations in Rubisco kinetics and their temperature dependence should incorporate a correlative analysis with variations in the large (L)-subunit and/or small (S)-subunit amino acid sequence. Such a complementary research would permit deciphering what residue substitutions determine the observed variability in Rubisco catalysis.

In this study, we examined Rubisco catalytic properties and their temperature dependence in 20 crop species, thereby constituting the largest published data set of its kind. The aims of this work were (1) to compare the Rubisco kinetic parameters among the most economically important crops, (2) to search for differences in the temperature response of the main kinetic parameters among these species, (3) to test whether crop Rubiscos are optimally suited for the conditions encountered in plant chloroplasts, and (4) to unravel key amino acid replacements putatively responsible for differences in Rubisco kinetics in crops.

RESULTS

The Variability in Rubisco Kinetics at 25°C among the Most Relevant Crop Species

When considering exclusively the 18 C3 crop species, at 25°C, the Rubisco Michaelis-Menten constant for CO2 under nonoxygenic (Kc) and 21% O2 (Kcair) varied approximately 2-fold and 3-fold, respectively, and the kcatc varied approximately 2-fold (Table I). For Kc and Kcair, Manihot esculenta presented the lowest values (Kc = 6.1 μm and Kcair = 10.8 μm) and Spinacia oleracea presented the highest (Kc = 14.1 μm and Kcair = 26.9 μm). Values for kcatc varied between 1.4 s−1 (M. esculenta) and 2.5 s−1 (Ipomoea batatas). The Rubisco Sc/o was the kinetic parameter with the lowest variation among the C3 species (Supplemental Fig. S1) and ranged between 92.4 mol mol–1 (Solanum lycopersicum) and 100.8 mol mol–1 (Beta vulgaris and M. esculenta; Table I). Brassica oleracea and Glycine max presented the lowest value for the Rubisco carboxylase catalytic efficiency, calculated as kcatc/Kc (0.17 s−1 μm−1), and Coffea arabica presented the lowest value for the kcatc/Kcair ratio (0.08 s−1 μm−1). With regard to the oxygenase catalytic efficiency (calculated as kcato/Ko), S. oleracea displayed the lowest value (1.76 s−1 nm−1). Hordeum vulgare presented the highest values for the Rubisco carboxylase and oxygenase catalytic efficiencies (kcatc/Kc = 0.28 s−1 μm−1, kcatc/Kcair = 0.17 s−1 μm−1, and kcato/Ko = 3.01 s−1 nm−1).

Table I. Kinetic parameters of crop Rubiscos measured at 25°C.

Parameters included Kc and Kcair, kcatc, Sc/o, and the carboxylation (kcatc/Kc and kcatc/Kcair) and the oxygenation (kcato/Ko) catalytic efficiencies. The kcato/Ko ratio was calculated as (kcatc/Kc)/Sc/o × 1,000. For each species, data are means ± se (n = 3–9). Group averages were obtained from individual measurements in each species. Different letters denote statistical differences (P < 0.05) by Duncan analysis between C3 and C4 groups.

| Species | Kc | Kcair | kcatc | Sc/o | kcatc/Kc | kcatc/Kcair | kcato/Ko |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | s−1 | mol mol−1 | s−1 μm−1 | s−1 μm−1 | s−1 nm−1 | |

| C3 species | |||||||

| Avena sativa | 10.8 ± 0.9 | 18.1 ± 2.0 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 99.9 ± 3.0 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 2.14 ± 0.06 |

| Beta vulgaris | 10.8 ± 1.2 | 18.6 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 100.8 ± 2.0 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 1.94 ± 0.31 |

| Brassica oleracea | 11.8 ± 0.1 | 19.2 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 96.2 ± 1.3 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 1.81 ± 0.28 |

| Capsicum annuum | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 19.8 ± 1.5 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 96.0 ± 4.5 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 1.98 ± 0.15 |

| Coffea arabica | 11.0 ± 0.4 | 22.9 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 98.7 ± 3.8 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 1.98 ± 0.18 |

| Cucurbita maxima | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 19.2 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 98.4 ± 0.4 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 2.45 ± 0.31 |

| Glycine max | 8.6 ± 0.2 | 16.2 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 97.0 ± 1.1 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 1.76 ± 0.21 |

| Hordeum vulgare | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 14.9 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 99.2 ± 3.8 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 3.01 ± 0.19 |

| Ipomoea batatas | 12.0 ± 0.7 | 21.1 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 98.5 ± 6.6 | 0.20 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 1.96 ± 0.08 |

| Lactuca sativa | 11.1 ± 0.3 | 18.2 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 94.0 ± 1.9 | 0.19 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 2.06 ± 0.07 |

| Manihot esculenta | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 10.8 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 100.8 ± 0.9 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 2.24 ± 0.17 |

| Medicago sativa | 9.7 ± 1.6 | 16.4 ± 1.9 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 95.6 ± 2.2 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 2.23 ± 0.36 |

| Oryza sativa | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 17.3 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 93.1 ± 1.2 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 2.73 ± 0.43 |

| Phaseolus vulgaris | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 99.7 ± 2.7 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 2.11 ± 0.17 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | 9.7 ± 0.4 | 16.6 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 92.4 ± 2.3 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 2.48 ± 0.20 |

| Solanum tuberosum | 9.6 ± 0.2 | 18.0 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 95.4 ± 2.3 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 2.32 ± 0.46 |

| Spinacia oleracea | 14.1 ± 0.8 | 26.9 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 97.0 ± 1.2 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 1.76 ± 0.13 |

| Triticum aestivum | 11.3 ± 0.4 | 16.0 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 100.1 ± 1.8 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 2.08 ± 0.24 |

| C3 average | 10.0 ± 0.3a | 18.0 ± 0.5a | 2.1 ± 0.1a | 97.5 ± 0.6a | 0.21 ± 0.01a | 0.12 ± 0.01a | 2.17 ± 0.07a |

| C4 species | |||||||

| Saccharum × officinarum | 26.3 ± 4.0 | 31.7 ± 2.1 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 82.2 ± 1.8 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 1.82 ± 0.35 |

| Zea mays | 31.6 ± 1.8 | 42.0 ± 2.8 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 87.3 ± 1.4 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 1.22 ± 0. 20 |

| C4 average | 27.6 ± 2.3b | 36.1 ± 2.6b | 4.0 ± 0.5b | 84.4 ± 1.5b | 0.13 ± 0.02b | 0.10 ± 0.01a | 1.52 ± 0.23b |

When data from the two C4 species (Saccharum × officinarum and Zea mays) were included in the comparison at 25°C, the range of variability increased for all parameters (Table I). Rubisco from the two C4 species presented higher kcatc but lower affinity for CO2 (i.e. higher Kc and Kcair and lower Sc/o) than Rubisco from C3 crops. On average, kcatc/Kc and kcato/Ko of C4 Rubiscos were 62% and 70% of those of C3 crop Rubiscos, respectively.

The Temperature Response of Rubisco Kinetics in Crops and Tradeoffs between Catalytic Traits

Both the range of variation and the species showing the extreme values of Rubisco kinetics at 15°C and 35°C were similar to those described at 25°C, with some exceptions. As at 25°C, among the C3 crops, Rubisco from M. esculenta presented the lowest values for Kc and Kcair at 15°C and 35°C, while the highest values were measured on Rubisco from S. oleracea (Supplemental Table S1). The lowest and highest values for kcatc at 15°C were those of Rubisco from Cucurbita maxima and H. vulgare, respectively. The degree of dispersion of the data and the range of variation between the maximum and minimum values for Kc, Kcair, and kcatc increased with the increment in the assay temperature (Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Fig. S1). Regarding Sc/o, values ranged between 116.1 mol mol−1 (B. oleracea) and 132.2 mol mol−1 (C. maxima) at 15°C and between 74.2 mol mol−1 (Oryza sativa) and 85 mol mol−1 (M. esculenta) at 35°C (Supplemental Table S1). As for Sc/o, the range of variation for kcatc/Kc and kcato/Ko also was narrowed with the increase in the assay temperature (Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Fig. S1).

Integrating all data across three assay temperatures, kcatc correlated positively with Kc for both C3 species (r2 = 0.82, P < 0.001) and C4 species (r2 = 0.94, P < 0.001), with Rubisco from C4 species showing higher Kc for a given kcatc than that from C3 species (Fig. 1A). The low interspecific variability in Sc/o within each assay temperature determined a nonlinear relationship between kcatc and Sc/o when considering data from all temperatures together (Fig. 1B). At each temperature individually, Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCCs) between kcatc and Kc and Sc/o were highly significant (Table II) when considering both C3 and C4 together. The results from the PICs analyses were in general more conservative compared with PCCs (Table II), and some significant correlations were lost with PICs (e.g. Sc/o versus Kc or Kcair at 25°C). Notably, when excluding the two C4 species, PCCs decreased in almost all correlations (Table II). Hence, the PCC between kcatc and Kc was no longer significant at 15°C, and the PCC between kcatc and Sc/o was significant only at 15°C. Furthermore, when considering only C3 species, the unique significant PICs between kcatc and Kc and Sc/o were those found between kcatc and Sc/o at 15°C and 25°C.

Figure 1.

Relationship of kcatc with Kc (A) and the Sc/o (B). Black symbols correspond to C3 species at 15°C (triangles), 25°C (circles), and 35°C (inverted triangles); white symbols correspond to C4 species at 15°C (triangles), 25°C (circles), and 35°C (inverted triangles). Each symbol represents the average value of a single species per temperature interaction.

Table II. PICs (top part of the diagonals) and PCCs (bottom part of the diagonals) between the Rubisco kinetic parameters Kc, Kcair, kcatc, and Sc/o at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C when considering the 20 C3 and C4 species together and the 18 C3 species alone.

Significant correlations are marked with asterisks: ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; and *, P < 0.05.

| 15°C |

25°C |

35°C |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kc | Kcair | kcatc | Sc/o | Kc | Kcair | kcatc | Sc/o | Kc | Kcair | kcatc | Sc/o | |

| Data from C3 and C4 species analyzed together | ||||||||||||

|

Kc |

0.826*** |

0.502* |

−0.314 |

0.913*** |

0.819*** |

−0.202 |

0.960*** |

0.710*** |

−0.775*** |

|||

|

Kcair |

0.927*** |

0.036 |

−0.099 |

0.946*** |

0.683*** |

0.037 |

0.962*** |

0.707*** |

−0.660** |

|||

|

kcatc |

0.810*** |

0.645** |

−0.660** |

0.941*** |

0.890*** |

−0.450* |

0.894*** |

0.858*** |

−0.634** |

|||

|

Sc/o |

−0.498* |

−0.361 |

−0.673** |

−0.772*** |

−0.699*** |

−0.749*** |

−0.806*** |

−0.737*** |

−0.736*** |

|||

| Data from C3 species alone | ||||||||||||

|

Kc |

0.900*** |

0.194 |

0.120 |

0.646** |

0.256 |

0.057 |

0.907*** |

0.363 |

−0.357 |

|||

|

Kcair |

0.892*** |

−0.118 |

0.394 |

0.829*** |

0.173 |

−0.006 |

0.816*** |

0.401 |

−0.155 |

|||

|

kcatc |

0.268 |

0.137 |

−0.787** |

0.698*** |

0.587* |

−0.470* |

0.613** |

0.476* |

−0.285 |

|||

| Sc/o | 0.025 | 0.145 | −0.496* | −0.049 | −0.162 | −0.083 | −0.386 | −0.157 | −0.259 | |||

The energy of activation (ΔHa) for Kc varied between 38.2 kJ mol−1 (Solanum tuberosum) and 83.1 kJ mol−1 (O. sativa; Table III). I. batatas (40.7 kJ mol−1) and M. esculenta (75.4 kJ mol−1) were the species showing the lowest and highest values for ΔHa of Kcair. As for kcatc, ΔHa varied between 27.9 kJ mol−1 (H. vulgare) and 60.5 kJ mol−1 (Medicago sativa). Although the range of variation across C3 species was similar for the energies of activation of both Kc and kcatc (2.2-fold), nonsignificant correlation was observed between ΔHa for Kc and ΔHa for kcatc in both conventional and phylogenetically independent analyses (r2 = 0.11 and 0.15, respectively, P > 0.05). The lowest and highest values for ΔHa of the CO2 compensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration (Γ*; calculated from Sc/o) were measured in B. vulgaris (19.8 kJ mol−1) and G. max (26.5 kJ mol−1), respectively. On average, Rubisco from C3 crops presented significantly higher ΔHa for Kc (60.9 ± 1.5 kJ mol−1) and kcatc (43.7 ± 1.5 kJ mol−1) than Rubisco from C4 species (Kc = 52.4 ± 5 kJ mol−1 and kcatc = 30.6 ± 1.6 kJ mol−1). By contrast, nonsignificant differences were observed in the average ΔHa for Γ* between C3 species (22.9 ± 0.4 kJ mol−1) and C4 species (25 ± 0.7 kJ mol−1).

Table III. ΔHa (kJ mol–1) and c (dimensionless) values of Kc (μmol mol–1) and Kcair (μmol mol–1), kcatc (s–1), and Γ* (μmol mol–1) for the 20 crop species.

For each species, data are means ± se (n = 3–9). Group averages were calculated from individual measurements in each species. Different letters denote statistical differences (P < 0.05) by Duncan analysis between C3 and C4 groups. Parameter concentrations of Kc (μm) and Kcair (μm) in liquid phase (Table I; Supplemental Table S1) were converted to gaseous phase partial pressures (Kc and/or Kcair [μmol mol–1] = parameter [μm] × Kh × air volume [L]/RT]. Kh is the hydrolysis constant (15°C = 22.2, 25°C = 29.4, and 35°C = 38.2). For the air volume (L): 15°C = 23.7, 25°C = 24.5, and 35°C = 25.4. The term Γ* (μmol mol –1) is derived from 0.5O/Sc/o, where O is the oxygen concentration.

| Species |

Kc |

Kcair |

kcatc |

Γ* |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c | ΔHa | c | ΔHa | c | ΔHa | c | ΔHa | |

| C3 species | ||||||||

| A. sativa | 31.3 ± 0.7 | 63.4 ± 2.0 | 26.0 ± 0.4 | 48.9 ± 1.2 | 17.6 ± 2.2 | 41.5 ± 5.5 | 13.3 ± 0.5 | 23.6 ± 1.4 |

| B. vulgaris | 28.7 ± 1.7 | 57.0 ± 4.4 | 27.2 ± 0.7 | 51.8 ± 1.8 | 21.5 ± 3.7 | 51.2 ± 9.6 | 11.7 ± 0.4 | 19.8 ± 1.0 |

| B. oleracea | 28.1 ± 1.1 | 55.3 ± 2.8 | 26.5 ± 0.9 | 50.1 ± 2.4 | 18.8 ± 2.6 | 45.7 ± 6.5 | 12.6 ± 0.2 | 21.8 ± 0.5 |

| C. annuum | 26.6 ± 1.5 | 51.8 ± 3.7 | 27.0 ± 1.6 | 51.2 ± 3.7 | 16.3 ± 2.8 | 39.2 ± 6.9 | 13.4 ± 0.7 | 24.1 ± 1.8 |

| C. arabica | 34.7 ± 0.3 | 71.5 ± 0.9 | 27.6 ± 1.8 | 52.2 ± 4.3 | 16.5 ± 2.6 | 39.0 ± 6.1 | 13.1 ± 0.5 | 23.4 ± 1.1 |

| C. maxima | 28.6 ± 0.8 | 57.0 ± 1.8 | 29.2 ± 1.1 | 56.8 ± 2.8 | 20.2 ± 1.0 | 48.7 ± 2.7 | 12.2 ± 0.9 | 21.1 ± 2.2 |

| G. max | 34.2 ± 0.5 | 71.1 ± 1.4 | 28.4 ± 1.2 | 55.3 ± 2.9 | 22.7 ± 2.5 | 55.2 ± 5.8 | 14.4 ± 1.7 | 26.5 ± 4.1 |

| H. vulgare | 31.1 ± 1.1 | 63.4 ± 3.0 | 30.7 ± 1.9 | 60.9 ± 5.0 | 12.2 ± 1.6 | 27.9 ± 4.0 | 12.3 ± 0.2 | 21.2 ± 0.6 |

| I. batatas | 23.0 ± 0.7 | 42.4 ± 1.6 | 22.7 ± 1.2 | 40.7 ± 3.1 | 14.3 ± 1.5 | 33.4 ± 3.8 | 13.0 ± 0.3 | 22.8 ± 0.8 |

| L. sativa | 28.3 ± 1.3 | 55.8 ± 3.2 | 29.0 ± 2.1 | 56.5 ± 5.2 | 14.1 ± 0.7 | 33.3 ± 1.7 | 12.3 ± 0.3 | 21.2 ± 0.9 |

| M. esculenta | 33.7 ± 1.4 | 70.8 ± 3.4 | 36.1 ± 1.1 | 75.4 ± 2.8 | 19.8 ± 1.6 | 47.4 ± 4.1 | 12.2 ± 0.2 | 21.1 ± 0.5 |

| M. sativa | 29.2 ± 1.3 | 58.8 ± 3.6 | 26.1 ± 0.4 | 49.5 ± 1.0 | 24.8 ± 1.1 | 60.5 ± 2.8 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | 20.1 ± 0.4 |

| O. sativa | 38.9 ± 0.8 | 83.1 ± 1.8 | 30.5 ± 1.2 | 60.5 ± 3.1 | 19.2 ± 1.8 | 46.4 ± 4.7 | 13.7 ± 0.5 | 24.6 ± 1.3 |

| P. vulgaris | 31.5 ± 0.8 | 64.6 ± 2.0 | 30.9 ± 2.7 | 61.7 ± 6.8 | 19.8 ± 2.1 | 47.7 ± 5.3 | 13.4 ± 0.6 | 24.1 ± 1.5 |

| S. lycopersicum | 30.8 ± 2.5 | 62.1 ± 6.3 | 36.0 ± 2.5 | 73.8 ± 6.4 | 14.7 ± 1.4 | 34.6 ± 3.6 | 12.5 ± 0.2 | 21.8 ± 0.5 |

| S. tuberosum | 21.1 ± 0.2 | 38.2 ± 0.5 | 24.4 ± 0.8 | 44.9 ± 1.9 | 19.2 ± 0.5 | 46.2 ± 1.1 | 13.7 ± 0.9 | 24.7 ± 2.2 |

| S. oleracea | 34.3 ± 0.8 | 69.9 ± 2.2 | 25.1 ± 0.5 | 45.6 ± 1.1 | 20.2 ± 0.7 | 48.0 ± 1.8 | 13.5 ± 0.3 | 25.2 ± 1.0 |

| T. aestivum | 30.1 ± 0.5 | 60.4 ± 2.2 | 34.4 ± 2.2 | 70.1 ± 5.4 | 17.4 ± 1.7 | 41.2 ± 4.3 | 13.5 ± 0.2 | 24.2 ± 0.4 |

| C3 average | 30.2 ± 0.6a | 60.9 ± 1.5a | 28.8 ± 0.6a | 55.9 ± 1.5a | 18.3 ± 0.6a | 43.7 ± 1.5a | 13.0 ± 0.2a | 22.9 ± 0.4a |

| C4 species | ||||||||

| S. officinarum | 30.2 ± 1.9 | 58.3 ± 5.0 | 32.0 ± 1.0 | 62.3 ± 2.7 | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 30.2 ± 3.5 | 14.3 ± 0.6 | 25.8 ± 1.4 |

| Z. mays | 24.7 ± 3.4 | 44.5 ± 8.5 | 24.7 ± 3.4 | 44.5 ± 8.5 | 14.0 ± 0.9 | 31.0 ± 1.9 | 13.6 ± 0.1 | 24.3 ± 0.2 |

| C4 average | 27.9 ± 2.0a | 52.4 ± 5.0b | 28.9 ± 0.8a | 53.7 ± 1.9a | 13.7 ± 0.7b | 30.6 ± 1.6b | 14.0 ± 0.3a | 25. 0 ± 0.7a |

The CO2 Assimilation Potential of Rubisco Kinetics in Crops

The CO2 assimilation potential of Rubisco (ARubisco) was modeled at varying temperature and CO2 availability at the catalytic site (chloroplastic CO2 concentration [Cc]) using the species-specific kinetic data measured at each temperature (Table I; Supplemental Table S1). The simulated value of Cc = 250 μbar is representative of that encountered in the chloroplast stroma of C3 species under well-watered conditions (Bermúdez et al., 2012; Scafaro et al., 2012; Galmés et al., 2013). Under mild to moderate water stress, when no metabolic impairment is present, the decrease in the stomatal and leaf mesophyll conductances to CO2 provokes a decrease in the concentration of CO2 in the chloroplast (Flexas et al., 2006). We selected a value of 150 μbar to simulate the Cc in water-stressed plants.

Differences in ARubisco across species were largely dependent on the temperature and the availability of CO2 for carboxylation (Fig. 2). This fact was due to the different prevalence of RuBP-saturated (Ac) and RuBP-limited (Aj) CO2 assimilation rates governing ARubisco under the contrasting temperature and Cc, assuming an invariable concentration of active Rubisco sites of 25 μmol m−2 for all species. At 15°C, Ac limited ARubisco at Cc of 150 μbar in nine species (indicated by asterisks in Fig. 2). At 15°C and Cc of 250 μbar, only six species were Ac limited (Capsicum annuum, C. maxima, M. sativa, O. sativa, S. tuberosum, and S. oleracea). At 25°C and 35°C, ARubisco was Ac limited in all C3 species irrespective of Cc.

Figure 2.

Simulated ARubisco for C3 and C4 species at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C and at Cc values of 250 μbar (A) and 150 μbar (B). Equations used to calculate ARubisco were those described in the biochemical model of C3 photosynthesis (Farquhar et al., 1980), as explained in “Materials and Methods.” Bars represent minimum values of Ac- and Aj-limited ARubisco. Asterisks beside the bars indicate Ac-limited ARubisco, and the absence of asterisks indicates Aj-limited ARubisco. The rates of electron transport were 60, 150, and 212 μmol m−2 s−1 at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, respectively. The concentration of active Rubisco sites was assumed to be invariable at 25 μmol m−2 for all species and environmental conditions. The values used for the Rubisco kinetic parameters (kcatc, Γ*, and Kcair) are those shown in Table I and Supplemental Table S1.

At 25°C, the best Rubisco was that from H. vulgare at both Cc values, while Rubisco from G. max yielded the lowest ARubisco (Fig. 2). Rubisco from B. vulgaris presented the best performance at 35°C irrespective of CO2 availability, while C. annuum and S. officinarum Rubisco gave the lowest ARubisco at Cc of 250 and 150 μbar, respectively. At 15°C and Cc of 250 μbar, the highest potential for CO2 assimilation was found in Rubisco from G. max, M. esculenta, and Triticum aestivum, while Rubisco from M. esculenta gave the highest ARubisco at 15°C and Cc of 150 μbar. Rubisco from C. maxima displayed the lowest ARubisco at 15°C, regardless of the CO2 availability. It is interesting that Rubisco from the two C4 species, in particular from S. officinarum, performed better than the average C3 Rubiscos when ARubisco was simulated according to the photosynthesis model for C3 leaves (Farquhar et al., 1980), at 15°C and 25°C under Cc of 250 μbar (Fig. 2A). At lower Cc (150 μbar), the C4 Rubiscos yielded higher ARubisco values than the average C3 Rubiscos at 15°C and lower values at 35°C, being similar at 25°C (Fig. 2B).

To test the performance of the different Rubiscos in the context of C4 photosynthesis, Ac was also modeled assuming Cc of 5,000 μbar and concentration of active Rubisco sites (E) of 15 μmol m−2. Under these conditions, the advantage of C4-type Rubisco kinetics of S. officinarum and Z. mays, characterized by higher kcatc and Kcair, became evident as providing higher Ac values at the three temperatures (data not shown). On average, at saturating CO2 and lower concentration of Rubisco catalytic sites, C4 Rubiscos yielded Ac of 35, 49, and 60 μmol m−2 s−1 at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, respectively, compared with the C3 Rubisco averages (10, 23, and 42 μmol m−2 s−1, respectively).

Positively Selected L-Subunit Residues: Relationship with Rubisco Kinetics

The phylogeny obtained with rbcL, matK, and ndhF genes matched the currently accepted angiosperm classification (Supplemental Fig. S2; Bremer et al., 2009). When considering all species together, 10 L-subunit residues were under positive selection: 94, 262, 281, 309, 439, 446, 449, 470, 477, and amino acid insert between residues 468 and 469. Moreover, positive selection was identified in specific L-subunit residues along branches leading to species with high and low Kc, high kcatc, and low Sc/o at 25°C and low ΔHa for Kc (Table IV). The residues under positive selection were located at different positions within the Rubisco tertiary structure and included functionally diverse sites participating in L-subunit intradimer and dimer-dimer interactions and interactions with S-subunits and with Rubisco activase (Table IV). No residue under positive selection was associated with ΔHa for Kcair, ΔHa for kcatc, or ΔHa for Sc/o.

Table IV. Amino acid replacements in the Rubisco L-subunit identified under positive selection by Bayes empirical Bayes analysis implemented in the PAML package (Yang et al., 2005; Yang, 2007) along branches of the phylogenetic tree leading to species with particular Rubisco properties.

| Residuea | Amino Acid Changes | Location of Residue | Interactionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Branches leading to species with Kc ≥ 26 μm and kcatc ≥ 3.9 s–1 at 25°C (C4 species) | |||

| 94** | D, E, K → P | ID, RA | |

| 446** | R → K | C terminus | |

| 469** | Insert of G or T before residue 469 | C terminus | ID |

| Branches leading to species with kcatc ≥ 2.5 s–1 at 25°C | |||

| 281** | A → S | Helix 4 | DD, SS |

| Branches leading to species with Kc ≥ 10.8 μm at 25°C | |||

| 439*** | A → T, V | Helix G | |

| 469* | Insert of G or T before residue 469 | C terminus | ID |

| 470* | A, E → K, P, Q | C terminus | ID |

| 477** | S → E, G, P, Q | C terminus | |

| Branches leading to species with Sc/o ≤ 94 mol mol–1 at 25°C | |||

| 309** | M → I | βF-strand | ID |

| Branches leading to species with ΔHa for Kc ≤ 56 kJ mol–1 | |||

| 262** | V → A, T | Loop 3 | S-subunit |

| 439* | R → T, V | Helix G | |

| 449** | C, S, T → A | C terminus | |

| 477** | K → E, G, P, Q | C terminus | |

Residue numbering is based on the S. oleracea sequence. Values for Bayesian posterior probabilities are as follows: *, >0.90; **, >0.95; and ***, >0.99.

Interactions in which the selected residues and/or residues within 5 Å of them are involved: DD, dimer-dimer interactions; ID, intradimer interactions; RA, interface for interactions with Rubisco activase; SS, interactions with small subunits (Ott et al., 2000; Spreitzer and Salvucci, 2002; Du et al., 2003).

DISCUSSION

Main Crops Possess Rubiscos with Different Performance at 25°C

The kinetic data reported in this study are consistent with the range reported previously for higher plants at 25°C (Yeoh et al., 1980, 1981; Bird et al., 1982; Jordan and Ogren, 1983; Kent and Tomany, 1995; Galmés et al., 2005, 2014a, 2014c; Ishikawa et al., 2009; Prins et al., 2016; Table I) and showing the existence of significant variation among species in the carboxylase catalytic efficiency under nonoxygenic conditions (kcatc/Kc) and atmospheric conditions (kcatc/Kcair). Recent reports related kcatc/Kc variation with the growth capacity in a group of closely related species with similar ecology (Galmés et al., 2014a), suggesting that improving this ratio would be an effective way to engineer a better Rubisco. Nevertheless, such an improvement becomes constrained by the tradeoffs between kcatc, Kc, and Sc/o (Tcherkez et al., 2006; Savir et al., 2010; Galmés et al., 2014a, 2014c). Here, we demonstrate that these tradeoffs, in particular kcatc versus Kc, hold when considering C3 and C4 species together, even after accounting for the phylogenetic signal in the data, and that they generally strengthen at increasing assay temperatures (Table II). However, most of these tradeoffs were lost when considering exclusively the C3 species (Table II), indicative that the broad-scale patterns of covariation between the Rubisco kinetic parameters may not hold at smaller scales, as observed previously in other angiosperm species (Galmés et al., 2014c).

The kcatc from Z. mays and S. officinarum was 2-fold higher than that of the C3 species, albeit at the expense of 3 times less affinity for CO2 (Table I). This finding agrees with previously described trends between C3 and C4 species (Ghannoum et al., 2005; Kubien et al., 2008; Ishikawa et al., 2009) and with the fact that C4 species present lower kcatc/Kc (Kubien et al., 2008; Perdomo et al., 2015a).

Unlike other reports (Sage, 2002; Ishikawa et al., 2009), the observed variation in the kinetic parameters at 25°C among C3 species was apparently not related to the thermal climate of their respective domestication regions (data not shown). It should be noted that the origin, and hence the climatic conditions, of the selected varieties could be different from the species center of domestication and that the different crop varieties may have accumulated adaptive changes to local conditions by means of artificial selection (Meyer et al., 2012). Intraspecific variability in Rubisco catalytic traits has been reported in T. aestivum (Galmés et al., 2014c) and H. vulgare (Rinehart et al., 1983), but how this variability among genotypes is related to the adaptation of Rubisco to local environments remains elusive.

The Rubisco Kinetic Parameters of the Main Crops Present Different Thermal Sensitivities

The observed temperature response of the Rubisco kinetic parameters confirms well-described trends of increases in kcatc and Kc and a decrease in Sc/o with increasing assay temperature (Table I; Supplemental Table S1; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Uemura et al., 1997; Galmés et al., 2005; Prins et al., 2016).

The temperature dependency of full Rubisco catalytic constants was first provided for Nicotiana tabacum using in vivo-based leaf gas-exchange analysis (Bernacchi et al., 2001). After that report, all studies dealing with the temperature response of photosynthesis assumed the temperature dependency parameters of N. tabacum Rubisco, irrespective of the modeled species, from annual herbs to trees and from cold- to warm-adapted species (Pons et al., 2009; Keenan et al., 2010; Yamori et al., 2010; Galmés et al., 2011; Bermúdez et al., 2012; Scafaro et al., 2012). Importantly, our data set constitutes the most unequivocal confirmation that different temperature sensitivities of Rubisco kinetic parameters exist among different species and that extrapolating the temperature response of a unique model species to other plants induces errors when modeling the temperature response of photosynthesis. In this sense, the in vitro results of this study support in vivo data showing different temperature dependencies of Rubisco catalytic constants in Arabidopsis thaliana and N. tabacum (Walker et al., 2013).

In general, the Rubisco constant affinities for CO2 (Kc and Kcair) were more sensitive to changes in the assay temperature (i.e. presented higher ΔHa) than kcatc and Γ* (Table III), in agreement with a recent study (Perdomo et al., 2015a). This fact is explained by the increase in the oxygenase catalytic efficiency (kcato/Ko) at increasing temperature. However, it should be remarked that the kcato/Ko ratio was calculated from the measured parameters Kc, kcatc, and Sc/o and that direct measurements of the oxygenase activity of Rubisco (e.g. by mass spectrometry; Cousins et al., 2010) should be undertaken to confirm this trend.

As at 25°C, the differences in the temperature dependencies of Rubisco kinetic parameters among C3 species were not related to the thermal environment of a species’ domestication region (data not shown). This finding contrasts with previous evidence suggesting that the temperature sensitivity of Rubisco kinetic properties has evolved to improve the enzyme’s performance according to the prevailing thermal environment to which each species is adapted (Sage, 2002; Galmés et al., 2005, 2015).

Although only two C4 species were included in this study, they presented lower ΔHa for Kc and for kcatc than most of the C3 species, in close agreement with trends observed recently by Perdomo et al. (2015a) in Flaveria spp. (Table III). A larger number of C4 species need to be surveyed to verify the existence of differences in the temperature dependence of Rubisco kinetics between C3 and C4 species.

How Do the Species-Specific Properties of Rubisco Kinetics and Their Temperature Sensitivity Impact the Potential Capacity of Rubisco to Assimilate CO2?

Modeling the effect of the species-specific Rubisco kinetics and temperature dependencies of Rubisco kinetics resulted in significant differences in ARubisco among the studied C3 crops (Fig. 2). This modeling exercise highlighted which species would most benefit from the genetic replacement of their native version of Rubisco by other foreign versions with improved performance. Notably, the modeling results clearly indicate that the performance of specific Rubiscos cannot be evaluated without considering the environmental conditions during catalysis, specifically the temperature and the Cc. This fact results from the different temperature dependencies of Rubisco kinetics among crops and from the different impacts that Rubisco kinetics have on the Ac and Aj governing ARubisco. Hence, at 15°C and Cc of 250 μbar, ARubisco was limited by Aj in most C3 species (12 out of 18), while it was limited by Ac in all C3 species at 25°C and 35°C irrespective of the Cc value.

Detailed examination of modeled ARubisco suggests that future efforts to enhance Rubisco efficiency should be directed at the following C3 species displaying the poorest performance: C. maxima and M. sativa at 15°C and both Cc values; G. max, C. annuum, and C. arabica at 25°C and 250 μbar; G. max, S. oleracea, C. annuum, and C. arabica at 25°C and 150 μbar; C. annuum, S. lycopersicum, and L. sativa at 35°C and 250 μbar; and C. annuum and S. lycopersicum at 35°C and 150 μbar.

In order to focus on the Rubisco catalytic traits, the modeling assumed invariable values for E (25 μmol m−2 s−1) and specific values for the rate of photosynthetic electron transport (J) and Cc. However, species adapt and plants acclimate to the prevailing thermal environment through changes in the concentration and/or activation of Rubisco and J (Yamasaki et al., 2002; Yamori et al., 2011). Similarly, stomatal and leaf mesophyll conductances to CO2 also vary in response to temperature (von Caemmerer and Evans, 2015). The growth temperature effects on these parameters would have altered the equilibrium between Ac and Aj and, indirectly, the consequences of different Rubisco kinetic traits on the CO2 assimilation potential. In the future, we aim to increase the accuracy of the present simulation by examining and including the species-specific values for stomatal and leaf mesophyll conductances, E, and J at varying environmental conditions.

The Analysis of Positive Selection in Branches Leading to Specific Rubisco Traits May Reveal Lineage-Specific Amino Acid Substitutions

We found 10 Rubisco L-subunit residues under positive selection (94, 262, 281, 309, 439, 446, 449, 469, 470, and 477; Table IV). With the exceptions of residues 469 and 477, these residues have been reported previously in other groups of plants, implying a relatively limited number of residues responsible for the Rubisco fine-tuning (Kapralov and Filatov, 2007; Christin et al., 2008; Iida et al., 2009; Kapralov et al., 2011, 2012; Galmés et al., 2014a, 2014c). However, despite widespread parallel evolution of amino acid replacements in the Rubisco sequence, solutions found in particular groups of plants may be quite different. For instance, there are only two common residues under positive selection out of 10 between this study and methodologically similar work with a different sampling design published earlier (Galmés et al., 2014c). This fact raises questions of epistatic interactions and residue coevolution within Rubisco (Wang et al., 2011) as well as residue coevolution and complementarity between Rubisco and its chaperones (Whitney et al., 2015), which both may prevent the evolution of identical amino acid replacements because of different genetic backgrounds.

We have not examined the species differences in the sequence of the Rubisco S-subunit. Some of the species included in this survey, like T. aestivum, possess a large number of S-subunit genes (rbcS) encoding different S-subunits (Galili et al., 1998). Previous reports have showed that species with identical L-subunits might have different Rubisco kinetics (Rosnow et al., 2015) and directly demonstrated that differences in the S-subunits might affect Rubisco catalytic traits (Ishikawa et al., 2011; Morita et al., 2014). Therefore, we cannot reject the idea that the observed differences in Rubisco kinetics, and their temperature dependence, among the studied crops are partially due to differences in the S-subunits.

CONCLUSION

This study confirms the significant variation in carboxylation efficiency and parameters that contribute to it among plant species and, to our knowledge, for the first time, provides full Rubisco kinetic profiles for the 20 most important crop species. Our data set could be used as an input for the next generation of species-specific models of leaf photosynthesis and its response to climate change, leading to more precise forecasts of changes in crop productivity and yield. These data could help to decide in which crops the CO2 assimilation potential and carboxylation efficiency of Rubisco might be improved via reengineering of native enzymes or by replacement with foreign ones, as there is no a one-size-fits-all solution. The design of future attempts at Rubisco engineering in crops should be based on surveys of Rubisco catalytic and genetic diversity with a particular stress on relatives of the crops in question. Growing knowledge of the Rubisco catalytic spectrum combined with existing engineering toolkits for Rubisco (Whitney and Sharwood 2008) and its chaperones (Whitney et al., 2015) give us hope that the Rubisco efficiency, and hence the photosynthetic capacity, of crops could be improved in the near future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Species Selection and Growth Conditions

The following 20 crop species were selected for study: Avena sativa ‘Forridena’, Beta vulgaris ‘Detroit’, Brassica oleracea var italica ‘Calabres’, Capsicum annuum ‘Picante’, Coffea arabica ‘Catuaí Vermelho IAC 44’, Cucurbita maxima ‘Totanera’, Glycine max ‘Ransom’, Hordeum vulgare ssp. vulgare ‘Morex’, Ipomoea batatas ‘Rosa de Málaga’, Lactuca sativa ‘Cogollo de Tudela’, Manihot esculenta, Medicago sativa ‘Aragón’, Oryza sativa ‘Bomba’, Phaseolus vulgaris ‘Contender’, Saccharum × officinarum (hybrid between Saccharum officinarum and Saccharum spontaneum), Solanum lycopersicum ‘Roma VF’, Solanum tuberosum ‘Erlanger’, Spinacia oleracea ‘Butterfly’, Triticum aestivum ‘Cajeme’, and Zea mays ‘Carella’. These species represent the most important crops in terms of worldwide production (http://faostat.fao.org/). C. arabica was selected as being the most important commodity in the international agricultural trade (DaMatta, 2004). Plants were grown from seeds under natural photoperiods in a glasshouse at the University of the Balearic Islands (Spain) during 2011 and 2012. Plants were grown in soil-based compost supplemented with slow-release fertilizer and frequently watered to avoid water stress. The air temperature in the glasshouse during the growth period was maintained between 15°C and 30°C.

Determination of Kc and kcatc

Rubisco Kc and Kcair were determined in crude extracts obtained as detailed by Galmés et al. (2014a). Rates of 14CO2 fixation were measured at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C using activated protein extracts in 7-mL septum-capped scintillation vials containing reaction buffer (100 mm Bicine-NaOH, pH 8, 20 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm RuBP, and about 100 W-A units of carbonic anhydrase) equilibrated previously with either N2 or a mixture of oxygen and N2 (21:79). Nine different concentrations of H14CO3– (0.1 to 9.4 mm, each with a specific radioactivity of 3.7 × 1010 Bq mol−1) were prepared in the scintillation vials as described previously (Galmés et al., 2014a). Assays at 35°C using Rubisco from C4 species required increasing H14CO3– up to 17.7 mm to reach saturating CO2 concentration in the aqueous phase. Assays were started by the addition of 10 μL of protein extract and stopped after 1 min by injection of 0.1 mL of 10 m formic acid. Acid-stable 14C was determined by liquid scintillation counting (LS 6500 Multi-Purpose Scintillation Counter; Beckman Coulter) following the removal of acid-labile 14C by evaporation. Kc and Kcair were determined from the fitted data as described elsewhere (Bird et al., 1982). Replicate measurements (n = 3–6) were made using different biological replicates for each species.

To obtain kcatc, the maximum rate of carboxylation was extrapolated from the Michaelis-Menten fit and divided by the number of Rubisco active sites in solution, quantified by [14C]CABP binding (Yokota and Canvin, 1985). Additional control assays undertaken as detailed by Galmés et al. (2014a) confirmed that the observed acid-stable 14C signal was uniquely the result of Rubisco catalytic activity.

Determination of Sc/o

Rubisco Sc/o was measured on purified extracts obtained as described by Gago et al. (2013). On the day of Sc/o measurement, highly concentrated Rubisco solutions were desalted by centrifugation through G-25 Sephadex columns equilibrated previously with CO2-free 0.1 m Bicine (pH 8.2) containing 20 mm MgCl2. The desalted solutions were made 10 mm with NaH14CO3 (1.85 × 1012 Bq mol−1) and 4 mm NaH2PO4 to activate Rubisco by incubation at 37.5°C for 40 min. Reaction mixtures were prepared in oxygen electrodes (Oxygraph; Hansatech Instruments) by first adding 0.95 mL of CO2-free assay buffer (100 mm Bicine, pH 8.2, 20 mm MgCl2, containing 0.015 mg of carbonic anhydrase). After the addition of 0.02 mL of 0.1 m NaH14CO3 (1.85 × 1012 Bq mol−1), the plug was fitted to the oxygen electrode vessel and enough activated Rubisco (20 μL) was added. The reaction was started by the injection of 10 μL of 25 mm RuBP to be completed between 2 and 7 min depending on the assay temperature. RuBP oxygenation was calculated from the oxygen consumption, and carboxylation was calculated from the amount of 14C incorporated into PGA when all the RuBP had been consumed (Galmés et al., 2014a). Measurements were performed at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, with three to nine biological replicates for each species and assayed temperature.

For all Rubisco assays, pH of the assay buffers was accurately adjusted at each temperature of measurement. The concentration of CO2 in solution in equilibrium with HCO3− was calculated assuming a pKa for carbonic acid of 6.19, 6.11, and 6.06 at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, respectively. The concentration of oxygen in solution was assumed to be 305.0, 253.4, and 219.4 nmol mL−1 at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, respectively (Truesdale and Downing, 1954).

Temperature Dependence Parameters of Rubisco Kinetics

To determine the temperature response of the Rubisco kinetic parameters from each species, values for Kc, Kcair, and Sc/o were first converted from concentrations to partial pressures. For this, solubilities for CO2 were considered to be 0.045, 0.034, and 0.0262 mol L−1 bar−1 at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, respectively. In turn, solubilities for oxygen of 0.0016, 0.0013, and 0.0011 mol L−1 bar−1 were used at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, respectively. The Γ* was obtained from Sc/o as described by von Caemmerer (2000) using the above solubilities for oxygen. Thereafter, values of Kc, Γ*, and kcatc at the three temperatures were fitted to an Arrhenius-type equation (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Harley and Tenhunen, 1991):

|

(1) |

where c is a scaling constant, R is the molar gas constant (8.314 J K−1 mol−1), and Tk is the absolute assay temperature.

CO2 Assimilation Potential of Crop Rubiscos at Varying Temperatures and CO2 Availability

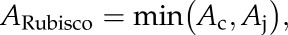

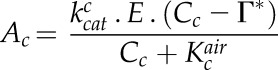

According to the biochemical model of C3 photosynthesis (Farquhar et al., 1980), ARubisco is defined as the minimum of Ac and Aj:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

ARubisco was obtained for each species at three different temperatures (15°C, 25°C, and 35°C) and two different Cc values (150 and 250 μbar), simulating situations of moderate water-stress and well-watered conditions in C3 plants, respectively (Flexas et al., 2006). The Rubisco catalytic traits kcatc, Γ*, and Kcair were taken from the species- and temperature-specific data obtained in this study. E was assumed to be invariable at 25 μmol m−2. Values of J were assumed to be 60, 150, and 212 μmol m−2 s−1 at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C, respectively, for all species. At 25°C, J = 150 μmol m−2 s−1 matches very well with a J/(kcatc × E) ratio of 1.5 (Egea et al., 2011). Values for J at 15°C and 35°C were obtained from the J temperature response described for Nicotiana tabacum by Walker et al. (2013).

Analysis of Rubisco L-Subunit Sites under Positive Selection

Full-length DNA sequences of the Rubisco L-subunit-encoding gene, rbcL (Supplemental Fig. S3), and two additional chloroplast genes (matK and ndhF) were obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) for the 20 studied species.

DNA sequences were translated into protein sequences for alignment using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). The software MODELTEST 3.7 (Posada and Crandall, 1998; Posada and Buckley, 2004) was used to check for the best model before running the phylogenetic analyses. The species phylogeny was reconstructed using concatenated alignment of all three chloroplast genes and maximum-likelihood inference conducted with RAxML version 7.2.6 (Stamatakis, 2006).

Amino acid residues under positive selection were identified using codon-based substitution models in comparative analysis of protein-coding DNA sequences within the phylogenetic framework (Yang, 1997). Given the conservative assumption of no selective pressure at synonymous sites, codon-based substitution models assume that codons with a ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rate (dN/dS) < 1 evolve under purifying selection to keep protein function and properties, while codons with dN/dS > 1 evolve under positive Darwinian selection to modify properties of the given protein (Yang, 1997).

The codeml program in the PAML version 4.7 package (Yang, 2007) was used to perform branch site tests of positive selection along prespecified foreground branches (Yang et al., 2005; Yang, 2007). The codeml A model allows 0 ≤ dN/dS ≤ 1 and dN/dS = 1 for all branches. dN/dS > 1 is permitted only along prespecified foreground branches, and 0 ≤ dN/dS ≤ 1 and dN/dS = 1 is permitted on background branches. Branches leading to species with high or low Kc, kcatc, Sc/o, and ΔHa were marked as foreground branches. For the purpose of these tests, high or low Kc, kcatc, and Sc/o ranges were taken only at 25°C, because of high correlation between values for these kinetic parameters obtained at three different temperatures. ΔHa for these kinetic parameters also was considered. The A model was used to identify the amino acid sites under positive selection and to calculate the posterior probability of an amino acid belonging to a class with dN/dS > 1 using the Bayes empirical Bayes approach implemented in PAML (Yang et al., 2005).

The Rubisco L-subunit residues were numbered based on the S. oleracea sequence. The location of sites under positive selection was done using the Rubisco protein structure from S. oleracea obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org; file 1RCX; Karkehabadi et al., 2003).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis consisted of one-way ANOVA and correlation for linear regressions. For all the parameters studied, a univariate model of fixed effects was assumed. The univariate general linear model for unbalanced data (Proc. GLM) was applied, and significant differences among species and groups of species were revealed by Duncan tests using IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, version 21.0. The relationships among the kinetic parameters and the temperature dependence parameters were tested with the square of the correlation coefficient observed for linear regressions using the tool implemented in R 3.1.1 (http://www.R-project.org). All statistical tests were considered significant at P < 0.05.

The PCC was calculated between pairwise combinations of the kinetic parameters Kc, Kcair, kcatc, and Sc/o at the three temperatures of measurement. However, correlations arising within groups of related taxa might reflect phylogenetic signal rather than true cause-effect relationships, because closely related taxa are not necessarily independent data points and could violate the assumption of randomized sampling employed by conventional statistical methods (Felsenstein, 1985). To overcome this issue, tests were performed for the presence of phylogenetic signal in the data, and trait correlations were calculated with PICs using the AOT module of PHYLOCOM (Webb et al., 2008) using the species phylogeny based on the three chloroplast genes (see below). All these tests were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Box-plot depiction of Rubisco kinetic parameters (Kc, Kcair, kcatc, and Sc/o) at 15°C, 25°C, and 35°C when considering the 18 C3 species alone.

Supplemental Figure S2. Maximum-likelihood phylogeny created using rbcL, matK, and ndhF for the selected crop species.

Supplemental Figure S3. Rubisco L-subunit amino acid alignment for the 20 crop species used in this study.

Supplemental Table S1. Rubisco kinetic parameters measured at 15°C and 35°C for the selected crop species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Trinidad Garcia for technical help and organization of the radioisotope installation at the Serveis Científico-Tècnics of the Universitat de les Illes Balears (UIB) while running these experiments; Miquel Truyols and collaborators of UIB Experimental Field and Greenhouses; Dr. Arantxa Molins (UIB) for experimental help; Dr. Cyril Douthe, Dr. Josep Cifre, Patricia González, and Dr. Jorge Gago (UIB) for help in improving different parts of the article; and Jaume Jaume and Dr. Sebastià Martorell (UIB) for providing some plant material used in the experiments.

Glossary

- kcatc

maximum carboxylase turnover rate

- Kc

Michaelis-Menten constant for CO2

- Sc/o

CO2-oxygen specificity

- Kcair

Michaelis-Menten constant for CO2 under 21% oxygen

- PICs

phylogenetically independent contrasts

- PCC

Pearson’s correlation coefficient

- ΔHa

energy of activation

- Γ*

CO2 compensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration

- ARubisco

CO2 assimilation potential of Rubisco

- Cc

chloroplastic CO2 concentration

- RuBP

ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate

- Ac

RuBP-saturated CO2 assimilation rate

- Aj

RuBP-limited CO2 assimilation rate

- E

concentration of active Rubisco sites

- J

photosynthetic electron transport rate

- dN/dS

ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitution rate

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (project nos. AGL2009–07999 and AGL2013–42364R to J.G.) and the Spanish Ministry of Education (FPI fellowship no. BES–2010–030796 to C.H.-C.).

References

- Badger MR. (1980) Kinetic properties of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from Anabaena variabilis. Arch Biochem Biophys 201: 247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Collatz GJ (1977) Studies on the kinetic mechanism of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and oxygenase reactions, with particular reference to the effect of temperature on kinetic parameters. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book 76: 355–361 [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer L, Afif D, Dizengremel P, Dreyer E (1996) Specificity factor of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase of Quercus robur. Plant Physiol Biochem 34: 879–883 [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez MA, Galmés J, Moreno I, Mullineaux PM, Gotor C, Romero LC (2012) Photosynthetic adaptation to length of day is dependent on S-sulfocysteine synthase activity in the thylakoid lumen. Plant Physiol 160: 274–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Portis AR, Nakano H, von Caemmerer S, Long SP (2002) Temperature response of mesophyll conductance: implications for the determination of Rubisco enzyme kinetics and for limitations to photosynthesis in vivo. Plant Physiol 130: 1992–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Singsaas EL, Pimentel C, Portis AR Jr, Long SP (2001) Improved temperature response functions for models of Rubisco‐limited photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 24: 253–259 [Google Scholar]

- Bird IF, Cornelius MJ, Keys AJ (1982) Affinity of RuBP carboxylases for carbon dioxide and inhibition of the enzymes by oxygen. J Exp Bot 33: 1004–1013 [Google Scholar]

- Bota J, Flexas J, Keys AJ, Loveland J, Parry MAJ, Medrano H (2002) CO2/O2 specificity factor of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.): first in vitro determination and comparison to in vivo estimations. Vitis 41: 163 [Google Scholar]

- Bremer B, Bremer K, Chase M, Fay M, Reveal J, Soltis D, Stevens P (2009) An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot J Linn Soc 161: 105–121 [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Farquhar GD (1985) Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light: estimates from gas-exchange measurements on spinach. Planta 165: 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrillo M. (1995) Ribulose-1,5-bis-phosphate carboxylase activity in altitudinal populations of Espeletia schultzii Wedd. Oecologia 101: 193–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot BF, Chabot JF, Billings WD (1972) Ribulose-1,5-diphosphate carboxylase activity in arctic and alpine populations of Oxyria digyna. Photosynthetica 6: 364–369 [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Salamin N, Muasya AM, Roalson EH, Russier F, Besnard G (2008) Evolutionary switch and genetic convergence on rbcL following the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Mol Biol Evol 25: 2361–2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Ghannoum O, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR (2010) Simultaneous determination of Rubisco carboxylase and oxygenase kinetic parameters in Triticum aestivum and Zea mays using membrane inlet mass spectrometry. Plant Cell Environ 33: 444–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaMatta FM. (2004) Exploring drought tolerance in coffee: a physiological approach with some insights for plant breeding. Braz J Plant Physiol 16: 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- Delgado E, Medrano H, Keys AJ, Parry MAJ (1995) Species variation in Rubisco specificity factor. J Exp Bot 46: 1775–1777 [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Espejo A. (2013) New challenges in modelling photosynthesis: temperature dependencies of Rubisco kinetics. Plant Cell Environ 36: 2104–2107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du YC, Peddi SR, Spreitzer RJ (2003) Assessment of structural and functional divergence far from the large subunit active site of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. J Biol Chem 278: 49401–49405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egea G, González-Real MM, Baille A, Nortes PA, Díaz-Espejo A (2011) Disentangling the contributions of ontogeny and water stress to photosynthetic limitations in almond trees. Plant Cell Environ 34: 962–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985) Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am Nat 125: 1–15 [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Galmés J, Gallé A, Gulías J, Pou A, Ribas-Carbó M, Tomás M, Medrano H (2010) Improving water use efficiency in grapevines: potential physiological targets for biotechnological improvement. Aust J Grape Wine Res 16: 106–121 [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbó M, Bota J, Galmés J, Henkle M, Martínez-Cañellas S, Medrano H (2006) Decreased Rubisco activity during water stress is not induced by decreased relative water content but related to conditions of low stomatal conductance and chloroplast CO2 concentration. New Phytol 172: 73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gago J, Coopman RE, Cabrera HM, Hermida C, Molins A, Conesa MÀ, Galmés J, Ribas-Carbó M, Flexas J (2013) Photosynthesis limitations in three fern species. Physiol Plant 149: 599–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili S, Avivi Y, Feldman M (1998) Differential expression of three RbcS subfamilies in wheat. Plant Sci 139: 185–193 [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Andralojc PJ, Kapralov MV, Flexas J, Keys AJ, Molins A, Parry MAJ, Conesa MÀ (2014a) Environmentally driven evolution of Rubisco and improved photosynthesis and growth within the C3 genus Limonium (Plumbaginaceae). New Phytol 203: 989–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Conesa MÀ, Díaz-Espejo A, Mir A, Perdomo JA, Niinemets U, Flexas J (2014b) Rubisco catalytic properties optimized for present and future climatic conditions. Plant Sci 226: 61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Flexas J, Keys AJ, Cifre J, Mitchell RAC, Madgwick PJ, Haslam RP, Medrano H, Parry MAJ (2005) Rubisco specificity factor tends to be larger in plant species from drier habitats and in species with persistent leaves. Plant Cell Environ 28: 571–579 [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Kapralov MV, Andralojc PJ, Conesa MÀ, Keys AJ, Parry MAJ, Flexas J (2014c) Expanding knowledge of the Rubisco kinetics variability in plant species: environmental and evolutionary trends. Plant Cell Environ 37: 1989–2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Kapralov MV, Copolovici LO, Hermida-Carrera C, Niinemets Ü (2015) Temperature responses of the Rubisco maximum carboxylase activity across domains of life: phylogenetic signals, trade-offs, and importance for carbon gain. Photosynth Res 123: 183–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Perdomo JA, Flexas J, Whitney SM (2013) Photosynthetic characterization of Rubisco transplantomic lines reveals alterations on photochemistry and mesophyll conductance. Photosynth Res 115: 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Ribas-Carbó M, Medrano H, Flexas J (2011) Rubisco activity in Mediterranean species is regulated by the chloroplastic CO2 concentration under water stress. J Exp Bot 62: 653–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum O, Evans JR, Chow WS, Andrews TJ, Conroy JP, von Caemmerer S (2005) Faster Rubisco is the key to superior nitrogen-use efficiency in NADP-malic enzyme relative to NAD-malic enzyme C4 grasses. Plant Physiol 137: 638–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornall J, Betts R, Burke E, Clark R, Camp J, Willett K, Wiltshire A (2010) Implications of climate change for agricultural productivity in the early twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365: 2973–2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall NP, Keys AJ (1983) Temperature dependence of the enzymic carboxylation and oxygenation of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate in relation to effects of temperature on photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 72: 945–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Tenhunen JD (1991) Modeling the photosynthetic response of C3 leaves to environmental factors. In Boote KJ, Loomis RS, eds, Modeling Crop Photosynthesis: From Biochemistry to Canopy. Crop Science Society of America/American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI, pp 17–39 [Google Scholar]

- Haslam RP, Keys AJ, Andralojc PJ, Madgwick PJ, Inger A, Grimsrud A, Eilertsen HC, Parry MAJ (2005) Specificity of diatom Rubisco. In Omasa K, Nouchi I, De Kok LJ, eds, Plant Responses to Air Pollution and Global Change. Springer-Verlag, Tokyo, pp 157–164 [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Miyagi A, Aoki S, Ito M, Kadono Y, Kosuge K (2009) Molecular adaptation of rbcL in the heterophyllous aquatic plant Potamogeton. PLoS ONE 4: e4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa C, Hatanaka T, Misoo S, Fukayama H (2009) Screening of high kcat Rubisco among Poaceae for improvement of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in rice. Plant Prod Sci 12: 345–350 [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa C, Hatanaka T, Misoo S, Miyake C, Fukayama H (2011) Functional incorporation of sorghum small subunit increases the catalytic turnover rate of Rubisco in transgenic rice. Plant Physiol 156: 1603–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DB, Ogren WL (1983) Species variation in kinetic properties of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys 227: 425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DB, Ogren WL (1984) The CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: dependence on ribulosebisphosphate concentration, pH and temperature. Planta 161: 308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane HJ, Viil J, Entsch B, Paul K, Morell MK, Andrews TJ (1994) An improved method for measuring the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase. Funct Plant Biol 21: 449–461 [Google Scholar]

- Kapralov MV, Filatov DA (2007) Widespread positive selection in the photosynthetic Rubisco enzyme. BMC Evol Biol 7: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapralov MV, Kubien DS, Andersson I, Filatov DA (2011) Changes in Rubisco kinetics during the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in Flaveria (Asteraceae) are associated with positive selection on genes encoding the enzyme. Mol Biol Evol 28: 1491–1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapralov MV, Smith JAC, Filatov DA (2012) Rubisco evolution in C4 eudicots: an analysis of Amaranthaceae sensu lato. PLoS ONE 7: e52974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkehabadi S, Taylor TC, Andersson I (2003) Calcium supports loop closure but not catalysis in Rubisco. J Mol Biol 334: 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan T, Sabate S, Gracia C (2010) Soil water stress and coupled photosynthesis-conductance models: bridging the gap between conflicting reports on the relative roles of stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis. Agric For Meteorol 150: 443–453 [Google Scholar]

- Kent SS, Tomany MJ (1995) The differential of the ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase specificity factor among higher plants and the potential for biomass enhancement. Plant Physiol Biochem 33: 71–80 [Google Scholar]

- Kubien DS, Whitney SM, Moore PV, Jesson LK (2008) The biochemistry of Rubisco in Flaveria. J Exp Bot 59: 1767–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing WA, Ogren WL, Hageman RH (1974) Regulation of soybean net photosynthetic CO2 fixation by the interaction of CO2, O2, and ribulose 1,5-diphosphate carboxylase. Plant Physiol 54: 678–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnherr B, Mächler F, Nösberger J (1985) Influence of temperature on the ratio of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase to oxygenase activities and on the ratio of photosynthesis to photorespiration of leaves. J Exp Bot 36: 1117–1125 [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RS, DuVal AE, Jensen HR (2012) Patterns and processes in crop domestication: an historical review and quantitative analysis of 203 global food crops. New Phytol 196: 29–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson RK, Stidham MA, Williams GJ, Edwards GE, Uribe EG (1982) Temperature dependence of photosynthesis in Agropyron smithii Rydb. I. Factors affecting net CO2 uptake in intact leaves and contribution from ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase measured in vivo and in vitro. Plant Physiol 69: 921–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K, Hatanaka T, Misoo S, Fukayama H (2014) Unusual small subunit that is not expressed in photosynthetic cells alters the catalytic properties of Rubisco in rice. Plant Physiol 164: 69–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchie EH, Pinto M, Horton P (2009) Agriculture and the new challenges for photosynthesis research. New Phytol 181: 532–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets U, Wright IJ, Evans JR (2009) Leaf mesophyll diffusion conductance in 35 Australian sclerophylls covering a broad range of foliage structural and physiological variation. J Exp Bot 60: 2433–2449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ort DR, Merchant SS, Alric J, Barkan A, Blankenship RE, Bock R, Croce R, Hanson MR, Hibberd JM, Long SP, et al. (2015) Redesigning photosynthesis to sustainably meet global food and bioenergy demand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 8529–8536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CM, Smith BD, Portis AR Jr, Spreitzer RJ (2000) Activase region on chloroplast ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: nonconservative substitution in the large subunit alters species specificity of protein interaction. J Biol Chem 275: 26241–26244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry MA, Andralojc PJ, Scales JC, Salvucci ME, Carmo-Silva AE, Alonso H, Whitney SM (2013) Rubisco activity and regulation as targets for crop improvement. J Exp Bot 64: 717–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry MA, Hawkesford MJ (2012) An integrated approach to crop genetic improvement. J Integr Plant Biol 54: 250–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry MAJ, Schmidt CNG, Cornelius MJ, Millard BN, Burton S, Gutteridge S, Dyer TA, Keys AJ (1987) Variations in properties of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from various species related to differences in amino acid sequences. J Exp Bot 38: 1260–1271 [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo JA, Cavanagh AP, Kubien DS, Galmés J (2015a) Temperature dependence of in vitro Rubisco kinetics in species of Flaveria with different photosynthetic mechanisms. Photosynth Res 124: 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo JA, Conesa MÀ, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbó M, Galmés J (2015b) Effects of long-term individual and combined water and temperature stress on the growth of rice, wheat and maize: relationship with morphological and physiological acclimation. Physiol Plant 155: 149–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TL, Flexas J, von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Genty B, Ribas-Carbó M, Brugnoli E (2009) Estimating mesophyll conductance to CO2: methodology, potential errors, and recommendations. J Exp Bot 60: 2217–2234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Buckley TR (2004) Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst Biol 53: 793–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA (1998) MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14: 817–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Orr DJ, Andralojc PJ, Reynolds MP, Carmo-Silva E, Parry MAJ (2016) Rubisco catalytic properties of wild and domesticated relatives provide scope for improving wheat photosynthesis. J Exp Bot 67: 1827–1838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart CA, Tingey SV, Andersen WR (1983) Variability of reaction kinetics for ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in a barley population. Plant Physiol 72: 76–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A. (2014) The use and misuse of Vc,max in Earth system models. Photosynth Res 119: 15–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow JJ, Evans MA, Kapralov MV, Cousins AB, Edwards GE, Roalson EH (2015) Kranz and single-cell forms of C4 plants in the subfamily Suaedoideae show kinetic C4 convergence for PEPC and Rubisco with divergent amino acid substitutions. J Exp Bot 66: 7347–7358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy H, Andrews TJ (2000) Rubisco: assembly and mechanism. In Leegood RC, Sharkey TD, von Caemmerer S, eds, Photosynthesis: Physiology and Metabolism. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 53–83 [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. (2002) Variation in the kcat of Rubisco in C3 and C4 plants and some implications for photosynthetic performance at high and low temperature. J Exp Bot 53: 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Cen YP, Li M (2002) The activation state of Rubisco directly limits photosynthesis at low CO2 and low O2 partial pressures. Photosynth Res 71: 241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Way DA, Kubien DS (2008) Rubisco, Rubisco activase, and global climate change. J Exp Bot 59: 1581–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savir Y, Noor E, Milo R, Tlusty T (2010) Cross-species analysis traces adaptation of Rubisco toward optimality in a low-dimensional landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3475–3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafaro AP, Yamori W, Carmo-Silva AE, Salvucci ME, von Caemmerer S, Atwell BJ (2012) Rubisco activity is associated with photosynthetic thermotolerance in a wild rice (Oryza meridionalis). Physiol Plant 146: 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer RJ, Salvucci ME (2002) Rubisco: structure, regulatory interactions, and possibilities for a better enzyme. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53: 449–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2006) RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22: 2688–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez GG, Farquhar GD, Andrews TJ (2006) Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7246–7251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truesdale GA, Downing AL (1954) Solubility of oxygen in water. Nature 173: 1236 [Google Scholar]

- Uemura K, Anwaruzzaman, Miyachi S, Yokota A (1997) Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from thermophilic red algae with a strong specificity for CO2 fixation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 233: 568–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. (2000) Biochemical Models of Leaf Photosynthesis. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. (2013) Steady-state models of photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1617–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR (2015) Temperature responses of mesophyll conductance differ greatly between species. Plant Cell Environ 38: 629–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B, Ariza LS, Kaines S, Badger MR, Cousins AB (2013) Temperature response of in vivo Rubisco kinetics and mesophyll conductance in Arabidopsis thaliana: comparisons to Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Environ 36: 2108–2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Kapralov MV, Anisimova M (2011) Coevolution of amino acid residues in the key photosynthetic enzyme Rubisco. BMC Evol Biol 11: 266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb CO, Ackerly DD, Kembel SW (2008) Phylocom: software for the analysis of phylogenetic community structure and trait evolution. Bioinformatics 24: 2098–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DJ, Andersen WR, Hess S, Hansen DJ, Gunasekaran M (1977) Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase from plants adapted to extreme environments. Plant Cell Physiol 18: 693–699 [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Birch R, Kelso C, Beck JL, Kapralov MV (2015) Improving recombinant Rubisco biogenesis, plant photosynthesis and growth by coexpressing its ancillary RAF1 chaperone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 3564–3569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Houtz RL, Alonso H (2011) Advancing our understanding and capacity to engineer nature’s CO2-sequestering enzyme, Rubisco. Plant Physiol 155: 27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Sharwood RE (2008) Construction of a tobacco master line to improve Rubisco engineering in chloroplasts. J Exp Bot 59: 1909–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki T, Yamakawa T, Yamane Y, Koike H, Satoh K, Katoh S (2002) Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis and related changes in photosystem II electron transport in winter wheat. Plant Physiol 128: 1087–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Nagai T, Makino A (2011) The rate-limiting step for CO2 assimilation at different temperatures is influenced by the leaf nitrogen content in several C3 crop species. Plant Cell Environ 34: 764–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Noguchi K, Hikosaka K, Terashima I (2010) Phenotypic plasticity in photosynthetic temperature acclimation among crop species with different cold tolerances. Plant Physiol 152: 388–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Suzuki K, Noguchi K, Nakai M, Terashima I (2006) Effects of Rubisco kinetics and Rubisco activation state on the temperature dependence of the photosynthetic rate in spinach leaves from contrasting growth temperatures. Plant Cell Environ 29: 1659–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, von Caemmerer S (2009) Effect of Rubisco activase deficiency on the temperature response of CO2 assimilation rate and Rubisco activation state: insights from transgenic tobacco with reduced amounts of Rubisco activase. Plant Physiol 151: 2073–2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]