Protocorm-like body development does not utilize the somatic embryogenesis program in Phalaenopsis aphrodite.

Abstract

The distinct reproductive program of orchids provides a unique evolutionary model with pollination-triggered ovule development and megasporogenesis, a modified embryogenesis program resulting in seeds with immature embryos, and mycorrhiza-induced seed germination. However, the molecular mechanisms that have evolved to establish these unparalleled developmental programs are largely unclear. Here, we conducted comparative studies of genome-wide gene expression of various reproductive tissues and captured the molecular events associated with distinct reproductive programs in Phalaenopsis aphrodite. Importantly, our data provide evidence to demonstrate that protocorm-like body (PLB) regeneration (the clonal regeneration practice used in the orchid industry) does not follow the embryogenesis program. Instead, we propose that SHOOT MERISTEMLESS, a class I KNOTTED-LIKE HOMEOBOX gene, is likely to play a role in PLB regeneration. Our studies challenge the current understanding of the embryonic identity of PLBs. Taken together, the data obtained establish a fundamental framework for orchid reproductive development and provide a valuable new resource to enable the prediction of gene regulatory networks that is required for specialized developmental programs of orchid species.

Orchids have a unique reproductive program. Unlike most flowering plants, whose ovules and embryo sacs are fully developed and whose egg cells are ready to be fertilized at anthesis, in some orchids, development of the ovule and embryo sac is triggered by pollination (Withner, 1959; Arditti, 1992; Yeung and Law, 1997). Pollination and fertilization are separated by relatively long periods during which the ovule and embryo sac develop. These periods vary among species and can span from as little as 4 d in Gastrodia elata to 10 months in Vanda suavis (Arditti, 1992). After fertilization, embryogenesis of the vast majority of orchids lacks characteristic organogenesis, and the embryos are arrested at the globular stage as seeds continue to mature and desiccate (Raghavan and Goh, 1994; Yu and Goh, 2001; Kull and Arditti, 2002). As a result, matured embryos of orchids do not have the embryonic leaves (cotyledons) and embryonic roots commonly established in other seed plants (Arditti, 1992; Dressler, 1993; Burger, 1998). Despite the incomplete morphogenesis, orchid embryos possess axis polarity and complete maturation and desiccation processes (Yeung et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2007a, 2007b, 2008).

The plant embryo is a miniature sporophyte developed from the zygote after fertilization. Plant embryogenesis is a genetically defined program comprising sequential developmental processes that result in a mature embryo in which the structural and functional organization of the adult plant is established. Two distinct but overlapping phases, morphogenesis and maturation, take place during embryogenesis (Bentsink and Koornneef, 2008; Braybrook and Harada, 2008). The basic body plan, including the organization of apical-basal polarity, the formation of functionally organized domains, and cell differentiation and tissue specification, is established during morphogenesis (Steeves and Sussex, 1989). Transcriptional regulators and signaling components are important to control axis polarity and the cell division plane (Jeong et al., 2012; Ueda and Laux, 2012). As morphogenesis approaches completion, embryos cease to grow and macromolecules start to be synthesized and accumulated as storage reserves. Abscisic acid plays an important role and is coordinated with a battery of transcriptional factors, such as ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3), FUSCA3 (FUS3), LEAFY COTYLEDON1 (LEC1), and LEC2, to regulate the accumulation of storage reserves and the timely acquisition of the desiccation process (Suzuki et al., 2003; Gazzarrini et al., 2004; Finkelstein et al., 2005; Kagaya et al., 2005a, 2005b). Failure to complete the maturation program in developing seeds leads to abscisic acid insensitivity, desiccation intolerance, reduced storage reserves, and/or precocious germination (Koornneef et al., 1984; Finkelstein and Somerville, 1990; Nambara et al., 1992; Lotan et al., 1998; Luerssen et al., 1998).

Germination and early seedling development of orchid seeds is not a spontaneous process and often requires species-specific mycorrhizal colonization (Smith and Read, 2008; Waterman and Bidartondo, 2008). It has been proposed that mycorrhizal colonization provides phosphate, nitrogen, or other mineral nutrients to support seed germination (Leake, 1994; Rasmussen, 2002). Orchid seeds germinate and form small spherical tuber-like bodies referred to as protocorms. Unlike the vast majority of plants, whose growth axes (shoot and root meristems) are established early during embryo development, the protocorm has only one meristematic domain at the anterior end where new leaves and roots are formed sequentially (Nishimura, 1981). Because protocorm development initiates organogenesis that is absent during the morphogenesis program of orchid embryogenesis, protocorm development is sometimes considered to be a continuum of zygotic embryogenesis (Jones and Tisserat, 1990; Ishii et al., 1998). However, the embryonic status of protocorms remains to be determined.

Protocorm-like bodies (PLBs) resemble protocorms structurally and are triggered from explants and/or calluses (Jones and Tisserat, 1990; Chugh et al., 2009). During the initiation of PLBs, callus cells from the explant form compact regions that are composed of meristemoids (promeristems; Lee et al., 2013). Polarized growth starts from the surface cells of each compact pool of meristemoids. Continued cell division produces anterior smaller cells that give rise to the shoot pole of a PLB and posterior larger and vacuolated cells that form at the base of a PLB (Lee et al., 2013). The first leaf is formed from the shoot pole of the PLB, and the root is usually produced at the base of the first leaf (Hong et al., 2008). Sometimes roots initiate from the middle or bottom of the PLB. As the clonal propagation of PLBs can be multiplied by cutting, it has become a routine practice in the orchid floriculture industry to generate clonal plantlets (Yam and Arditti, 2009).

Because the protocorm is considered to be an extended state of the zygotic embryo, the initiation and development of PLBs is referred to as somatic embryogenesis (Begum et al., 1994; Chang and Chang, 1998; Ishii et al., 1998; Chen and Chang, 2006; Zhao et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2013). However, molecular evidence supporting such a hypothesis remains limited. Here, we describe genome-wide gene activity in ovary tissues containing developing ovules and embryos from fertilization to maturity as well as in protocorm and PLB tissues of Phalaenopsis aphrodite. Our study reveals that the molecular components required for plant ovule and embryo development are evolutionarily conserved in P. aphrodite and provides new insights into the molecular dynamics that characterize the reproductive program of Phalaenopsis spp. orchids. Moreover, our data show that protocorms and PLBs share similar transcriptomic signatures that are mostly different from those of zygotic embryos. Furthermore, the initiation and developmental processes of orchid PLBs do not follow the somatic embryogenesis program but instead show a distinct regeneration program. We report that SHOOT MERISTEMLESS, a class I KNOTTED-LIKE HOMEOBOX gene, is likely to play an important role in PLB regeneration. Our studies challenge the current understanding of the embryonic identity of PLBs and suggest an alternative pathway for PLB regeneration.

RESULTS

De Novo Transcriptome Assembly

To ensure full-spectrum coverage of transcripts whose expression is important/required for general and tissue-specific proliferation and the maintenance of meristematic tissues, a reference transcriptome library was generated by paired-end sequencing mRNA populations collected from different meristematic tissues, including developing ovaries containing developing ovules collected at 30, 40, 50, and 60 d after pollination (DAP; Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1) and developing embryos collected at 70, 80, 90, 100, 120, 140, 160, 180, and 200 DAP (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1), developing protocorms (Fig. 1B), developing PLBs (Fig. 1C), newly emerging young leaves (less than 2 cm), emerging stalk buds (less than 2 cm), 5- to 10-cm floral stalks, root tips (less than 2 cm), and floral buds (less than 5 mm). The total size of the assembly was approximately 117 Mb. A summary of assembly statistics is given in Supplemental Table S1. This assembly yielded 112,467 unigenes that are longer than 200 nucleotides, with a mean unigene size of 1,038 nucleotides and a maximum unigene size of 15,584 nucleotides. This transcriptome provides the comprehensive transcript repertoire from various P. aphrodite meristems.

Figure 1.

Fertilization-triggered reproductive program, protocorm, and PLB development. A, Schematic diagram showing the time line of reproductive development in Phalaenopsis spp. orchids. Images show developing ovules or seeds in developing ovaries collected at the specified DAP (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Bars = 100 μm. The red asterisks indicate the developing ovule, and the black asterisks indicate the developing seed. Note that the seed coat turns brown at 180 DAP. B, Images of developing protocorms at 10 d (protocorm10), 20 d (protocorm20), or 30 d (protocorm30) after germination. A, Anterior end of the protocorm; P, posterior end of the protocorm. Bars = 1 mm. C, Images of developing PLBs in small (PLBS), medium (PLBM), and large (PLBL) sizes. Bar = 1 mm.

Different Sets of Coexpressed Genes Characterize Reproductive Development in P. aphrodite

To compare the transcriptome dynamics of protocorms, PLBs, ovary tissues spanning from ovule development to embryogenesis, young leaves, stalk buds, and floral stalks, 10-Mb single-end mRNA reads from each group of tissues (see “Materials and Methods”) were mapped to the assembled reference transcriptome and analyzed by principal component analysis. The mapping read analyses are summarized in Supplemental Table S2. Four distinct groups were identified by the analysis (Fig. 2A): (1) ovaries containing developing ovules (30–40 and 50–60 DAP) and developing embryos (70–80 and 90–120 DAP); (2) ovaries containing maturating embryos (140–160 and 180–200 DAP); (3) protocorms and PLBs; and (4) young leaves, emerging stalk buds, and floral stalks. Developmental time frames identified as being closely associated are likely to share the greatest similarity in overall gene expression and, therefore, are likely to share cellular functions.

Figure 2.

Protocorms and PLBs are molecularly distinct from other reproductive tissues. A, Principal component analysis of developing ovaries at 30 to 40, 50 to 60, 70 to 80, 90 to 120, 140 to 160, and 180 to 200 DAP, PLBs, protocorms, young leaves, stalk buds, and floral stalks. B, Heat map showing the P value significance of enrichment of GO terms for stage-specific mRNAs. Empty cells indicate a lack of association.

We were interested in understanding the extent to which gene expression was coordinated during developmental periods such as fertilization, embryo development, seed maturation, and protocorm and PLB development. K-mean analysis was applied to the RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data set to identify genes whose expression was preferentially enriched in specific tissues. To reduce false-positive results, only transcripts expressed (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads [FPKM] ≥ 5) in at least one tissue were selected. To increase the stringency, an equal to or greater than 10-fold change in at least two tissues was chosen as a cutoff. Twelve clusters representing stage-specific or tissue-specific enriched transcripts were identified (Supplemental Fig. S1B) and are listed in Supplemental Table S3. These transcripts encode a range of functional categories, although some of the encoded proteins had no known functions (Supplemental Data Set S1). Gene Ontology (GO) category enrichment analysis was applied to these clusters to identify predominant cellular processes associated with developing ovaries, protocorms, and PLBs (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Data Set S2). A detailed list of clustered transcripts and their GO terms is given in Supplemental Data Set S1.

After pollination, as the ovary started to develop at 30 to 40 DAP (Supplemental Fig. S1B, I), transcripts associated with cell cycle-associated biological processes, such as the cell cycle, cytokinesis by cell plate formation, DNA replication initiation, microtubule cytoskeleton organization, cell division, and regulation of the cell cycle, are strongly enriched (Fig. 2B). As development proceeded to 50 to 60 DAP (Supplemental Fig. S1B, II), genes involved in metal ion transport, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase activity, and Ser-type peptidase activity were represented (Fig. 2B). At around 70 to 80 DAP (Supplemental Fig. S1B, III), when fertilization had occurred and embryos started to develop in ovary tissues (Nadeau et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2008), the production of small interfering RNAs involved in RNA interference, DNA methylation, and methyltransferase activity were overrepresented (Fig. 2B). As embryos continued to develop in ovaries at 90 to 120 DAP and 140 to 160 DAP (Supplemental Fig. S1B, IV and V), transcripts encoded by genes associated with catabolism and macromolecular transport and storage such as lipid transport, carbohydrate transport, DNA catabolic processes, and sugar transmembrane transporter activity were significantly enriched (Fig. 2B). As the ovary reached maturity (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. S1B, VI), transcripts of genes involved in antiporter activity, the ubiquitin ligase complex, and the oxidation reduction process were enriched (Fig. 2B).

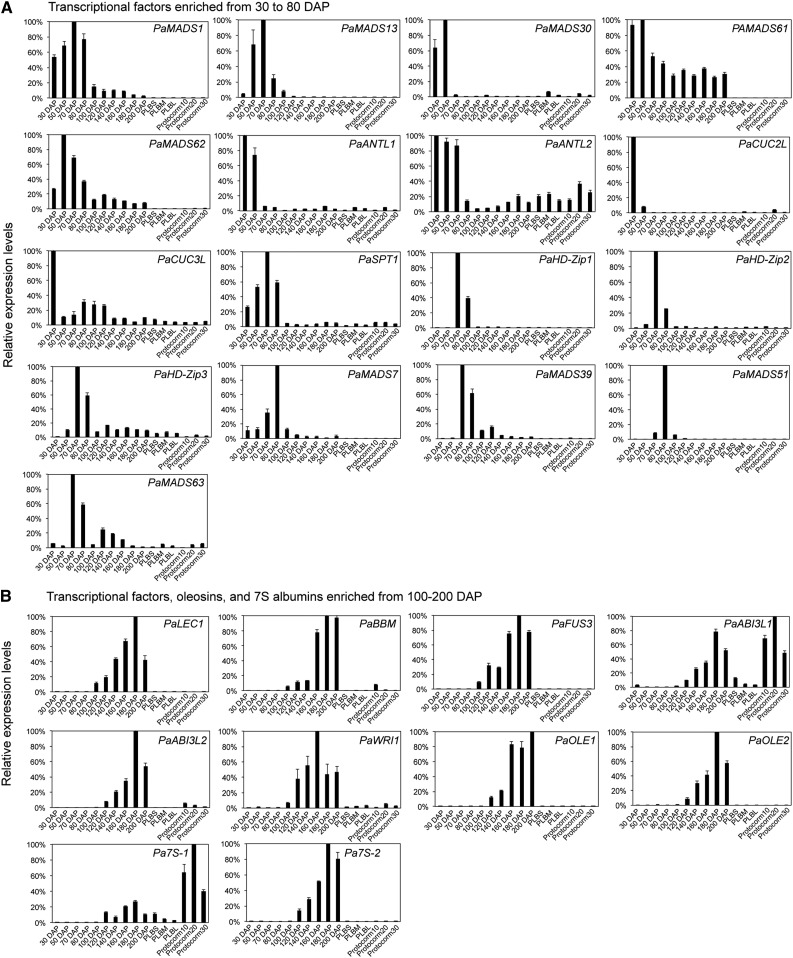

Figure 3.

Expression profiles of selected genes during reproductive development. A, Expression patterns of TFs enriched in developing ovaries from 30 to 80 DAP. B, Expression patterns of genes enriched in developing ovaries from 100 to 200 DAP. Small PLBs (PLBS), medium PLBs (PLBM), large PLBs (PLBL), 10-d-old protocorms (protocorm10), 20-d-old protocorms (protocorm20), and 30-d-old protocorms (protocorm30) are indicated.

GO analysis of the K-mean clusters VII, VIII, and IX revealed that cellular processes involved in oxidation reduction processes, heme binding, peroxidase activity, and copper ion binding were strongly enriched in both protocorms and PLBs (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S1B). Transcripts encoded by genes associated with terpene synthase activity, lyase activity, nucleoside triphosphatase activity, lipid metabolic processes, and the abscisic acid-activated signaling pathway were significantly enriched only in PLB tissues.

Transcription Factors Enriched before, during, and after Fertilization in Ovary Tissues

To survey the regulatory network controlling developmental transitions during orchid reproductive development, we used the GO category of regulation of transcription, DNA-templated to identify tissue- or stage-specific transcription factors (TFs) enriched in each cluster (Table I; Supplemental Data Set S3). Transcripts of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) orthologs previously shown to regulate carpel and ovule development, such as AGAMOUS (PaMADS1 and PaMADS61), SEPALLATA (PaMADS13), AINTEGUMENTA (PaANT), CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (PaCUC), and SPATULA (PaSPT; Elliott et al., 1996; Favaro et al., 2003; Pinyopich et al., 2003; Brambilla et al., 2007; Nahar et al., 2012; Galbiati et al., 2013), were overrepresented in ovary tissues collected from 30 to 60 DAP, during which ovules were developing. A homeobox TF, O39, isolated previously as an ovule-specific cDNA of Phalaenopsis spp. orchids (Nadeau et al., 1996), also was identified in our data set (PaHD-Zip4; Table I). The nomenclature of MADS domain TFs of P. aphrodite follows that of Phalaenopsis equestris (Cai et al., 2015). Three additional MADS domain factors, PaMADS61, PaMADS62, and PaMADS63, were identified in this study (Supplemental Fig. S2A).

Table I. Comparative transcript abundances of selected TFs and overrepresented genes in reproductive tissues of P. aphrodite by RNA-seq analysis.

Asterisks indicate that the expression pattern of the selected transcripts was confirmed by qRT-PCR.

| Transcript Identifier | Annotation |

FPKM Values |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–40 DAP | 50–60 DAP | 70–80 DAP | 90–120 DAP | 140–160 DAP | 180–200 DAP | PLBs | Protocorms | Young Leaves | Stalk Buds | Floral Stalks | ||

| TFs and cell cycle genes enriched at 30 to 60 DAP | ||||||||||||

| orchid.id50198.tr203744* | PaANTL1 | 67.2 | 27.7 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 10.0 | 0.1 | 2.8 |

| orchid.id163296.tr203744* | PaANTL2 | 80.4 | 54.4 | 7.5 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 30.0 | 34.8 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 8.9 |

| orchid.id135459.tr456992* | PaCUC2L | 23.4 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| orchid.id124656.tr357947* | PaCUC3L | 29.7 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| orchid.id150950.tr242911 | PaHD-Zip4 | 127.1 | 104.3 | 84.1 | 47.8 | 32.5 | 54.0 | 20.1 | 45.1 | 31.1 | 6.4 | 11.3 |

| orchid.id121128.tr255012* | PaMADS1 (AG-like) | 138.3 | 118.5 | 77.7 | 35.9 | 24.3 | 12.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| orchid.id127983.tr216633* | PaMADS7 (SHP/STK-like) | 244.1 | 274.3 | 434.6 | 515.0 | 173.4 | 113.8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| orchid.id125975.tr36909* | PaMADS13 (SEP-like) | 8.9 | 87.9 | 43.2 | 14.0 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id5222.tr206845* | PaMADS30 | 16.9 | 15.9 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 4.0 |

| orchid.id125352.tr345834* | PaMADS61 (AG-like) | 310.5 | 179.7 | 61.9 | 92.7 | 77.9 | 88.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| orchid.id126107.tr333603* | PaMADS62 (AGL6-like) | 14.2 | 36.4 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 12.0 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| orchid.id122032.tr208541* | PaSPT | 16.1 | 12.6 | 18.2 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| TFs and methyltransferases enriched at 70 to 80 DAP | ||||||||||||

| orchid.id139127.tr218563* | PaHD-Zip1 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 340.0 | 20.0 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 4.4 | 0.7 |

| orchid.id134449.tr70997* | PaHD-Zip2 | 0.8 | 6.3 | 24.6 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 6.1 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| orchid.id126646.tr143303* | PaHD-Zip3 | 1.7 | 19.4 | 62.1 | 25.2 | 28.3 | 22.7 | 32.2 | 5.6 | 2.7 | 26.1 | 13.2 |

| orchid.id161716.tr186472* | PaMADS39 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 10.4 | 6.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id2086.tr469871* | PaMADS51 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| orchid.id123254.tr4585* | PaMADS63 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 9.2 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 4.3 |

| TFs enriched from 90 to 200 DAP | ||||||||||||

| orchid.id67332.tr200912* | PaABI3L1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 12.9 | 17.2 | 0.9 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id133554.tr200912* | PaABI3L2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 16.3 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id116714.tr43006* | PaBBM | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.18 | 3.6 | 16.0 | 31.3 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id139573.tr88217* | PaFUS3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.6 | 21.9 | 23.7 | 0 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id150115.tr415912* | PaLEC1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 16.7 | 48.5 | 34.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id143578.tr366311* | PaOLE1 | 7.9 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 160.4 | 2,707.3 | 2,655.9 | 16.2 | 21.0 | 7.8 | 5.7 | 7.8 |

| orchid.id145648.tr244338* | PaOLE2 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 2.1 | 18.6 | 514.9 | 417.6 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 8.7 | 7.8 |

| orchid.id116824.tr161699* | PaWRI1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.7 | 71.6 | 27.8 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| TFs and redox-related genes enriched in PLB/protocorm tissues | ||||||||||||

| orchid.id125076.tr240339* | PaSTM | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 6.2 | 130.2 | 50.8 | 0.0 | 30.3 | 42.7 |

| orchid.id158957.tr258501* | PaERF1 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 47.5 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 6.5 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id152501.tr67371* | PaERF2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 24.0 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id130709.tr95546* | PaGA2OX1 | 8.2 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 78.2 | 15.0 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 0.5 |

| Other genes potentially expressed during embryogenesis | ||||||||||||

| orchid.id37769.tr82551 | PaSERK1 | 24.1 | 29.4 | 32.6 | 24.1 | 27.1 | 29.7 | 33.5 | 32.6 | 27.5 | 30.7 | 31.2 |

| orchid.id150215.tr82551 | PaSERK2 | 19.1 | 23.1 | 28.5 | 23.2 | 16.9 | 20.4 | 18.8 | 18.2 | 13.2 | 17.7 | 16.8 |

| orchid.id3634.tr252953 | PaSERK5 | 19.8 | 16.3 | 19.0 | 9.1 | 14.7 | 13.4 | 6.7 | 10.9 | 12.3 | 9.3 | 8.9 |

| orchid.id144614.tr49090 | PaWUS | 3.4 | 10.0 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| orchid.id2505.tr321179 | PaWOX3L | 0.1 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| orchid.id113505.tr105411 | PaWOX9L | 428.7 | 69.5 | 38.5 | 53.3 | 100.8 | 111.6 | 1.6 | 11.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| orchid.id128322.tr67670 | PaWOX11L | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 30.2 | 28.9 | 5.2 | 15.7 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.2 |

| orchid.id132756.tr477411 | PaWOX13L | 65.0 | 67.3 | 24.6 | 51.9 | 45.2 | 27.8 | 35.5 | 48.8 | 45.0 | 236.7 | 175.7 |

| orchid.id110412.tr133742* | Pa7S-1 | 8.3 | 12.8 | 8.9 | 170.0 | 463.0 | 701.5 | 670.1 | 7096.0 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 6.1 |

| orchid.id115955.tr204991* | Pa7S-2 | 24.3 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 1,770.6 | 1,7708.7 | 3,2717.4 | 25.8 | 102.0 | 9.2 | 11.2 | 7.2 |

| orchid.id3581.tr112811 | Pa7S-3 | 10.8 | 13.6 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 16.4 | 21.1 | 23.1 | 51.1 | 46.2 | 35.5 | 164.8 |

| orchid.id122139.tr112811 | Pa7S-4 | 16.8 | 18.7 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 24.7 | 30.9 | 43.8 | 98.3 | 66.2 | 67.2 | 254.2 |

| orchid.id1524.tr282965 | Pa11S-1 | 28.0 | 7.5 | 8.7 | 11.6 | 17.4 | 20.8 | 28.5 | 11.7 | 42.4 | 58.6 | 52.1 |

As ovary development proceeded to 70 to 80 DAP, when fertilization occurred, mRNAs of four MADS domain (PaMADS7-SHATTERPROOF/SEEDSTICK-like, PaMADS39, PaMADS51, and PaMADS63) and three homeodomain-Leu zipper (HD-Zip) family TFs were found to be enriched (Table I). The expression patterns of selected transcripts listed in Table I were confirmed independently by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3A). The phylogenetic relationship of the identified orchid proteins and their Arabidopsis counterparts is shown in Supplemental Figure S2, A to C.

As ovary development proceeded from 90 to 200 DAP, many seed-specific TFs, such as BABY BOOM (PaBBM), PaLEC1, PaFUS3, PaABI3L1, PaABI3L2, and WRINKLED1 (PaWRI1), were preferentially expressed (Table I). The identities of these embryonic marker genes were supported by phylogenetic analysis (Supplemental Fig. S2, B and D) and sequence alignment (Supplemental Fig. S3). qRT-PCR confirmed that mRNAs of PaBBM, PaLEC1, PaABI3L1, PaABI3L2, and PaFUS3 started to accumulate in ovary tissues at 100 DAP and reached a peak at 180 DAP (Fig. 3B). The expression pattern of PaWRI1 mRNA followed a similar pattern except that its accumulation peaked at 160 DAP. The maturation status of the developing seeds was marked by the expression of two seed maturation markers, OLEOSIN1 (PaOLE1) and PaOLE2 (Table I; Fig. 3B). The preferential accumulation of PaBBM and PaLEC1 mRNAs in developing embryos was further confirmed by in situ hybridization, with both mRNAs starting to accumulate in developing embryos 80 DAP (early stage of seed development; Fig. 4A). The PaBBM mRNA level continued to increase from 110 to 180 DAP and reached a peak when embryos approached the end of maturation. PaLEC1 mRNA, on the other hand, reached a peak in embryos at 140 DAP and was maintained at a relatively high level from 160 to 180 DAP.

Figure 4.

PaBBM and PaLEC1 mRNAs are present in developing embryos but not PLBs. A, In situ hybridization with an antisense (AS) PaBBM or PaLEC1 on longitudinal sections through the center of the developing seeds at different DAP. Sense probes (S) of PaBBM or PaLEC1 were used as a negative control. E, Embryo; white asterisks indicate the seed coat. Bars = 20 μm. B, In situ hybridization with antisense probe PaBBM-AS on longitudinal sections through the center of emerging PLBs. Bars = 200 μm. C, In situ hybridization with antisense probe PaLEC1-AS on longitudinal sections through the center of emerging PLBs. Black asterisks indicate individual PLBs. Bars = 200 μm.

Two 7S Globulins Are Preferentially Accumulated in Developing Seeds

During orchid seed development, storage proteins are synthesized and form protein bodies in developing embryos (Lee et al., 2006; Yang and Lee, 2014). We were interested to learn the compositions of the protein reserve and surveyed the expression patterns of the major seed storage protein, albumins, globulins, and prolamins (Shewry et al., 1995). At least one 11S globulin and four 7S globulins were identified from our transcriptome database, and their transcript abundance is shown in Table I. The phylogenetic relationship of the full-length proteins encoded by the 11S globulin and two 7S globulins is shown in Supplemental Figure S4. Notably, transcripts of two 7S globulin genes, Pa7S-1 and Pa7S-2, accumulated steadily during the seed maturation process with a peak at 180 DAP (Fig. 3B), suggesting that they are the major storage proteins in orchid seeds. In addition to developing seeds, Pa7S-1 mRNA was extremely abundant in protocorms. Intriguingly, prolamin and 2S albumin, the storage proteins commonly found in endosperms, were not identified in our transcriptome database and two publicly available orchid transcriptome databases (Su et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2015).

Embryo-Specific Markers Are Not Enriched in Protocorm and PLB Tissues

The expression of embryonic markers such as BBM, LEC1, FUS3, and ABI3s is not only enriched in zygotic and somatic embryos, but some of their functions also have been demonstrated to be sufficient to establish embryonic fate during somatic embryogenesis (Braybrook and Harada, 2008; Smertenko and Bozhkov, 2014). Unlike somatic embryonic tissues observed in other plant species, PaLEC1 and PaFUS3 mRNAs were hardly detectable in protocorms and PLBs. The mRNAs of PaBBM and PaABI3L2 accumulated to low levels in 10-d-old protocorms and were hardly detectable in developing PLBs (Table I; Fig. 3B). The level of PaABIL1 mRNA was relatively high in abundance in developing protocorms and low in abundance in developing PLBs (Table I; Fig. 3B). In addition, mRNAs of the two embryonic marker genes, PaWRI1 and PaOLE1, whose functions are important for the accumulation of storage reserves during the maturation phase of embryogenesis (Cernac and Benning, 2004; Hsieh and Huang, 2004), were expressed in very low abundance or were undetectable in developing protocorms and PLBs. In situ hybridization also confirmed the lack of detectable PaLEC1 and PaBBM mRNAs in developing PLBs (Fig. 4, B and C). Therefore, the expression of the embryonic marker genes was not correlated with the initiation and development of PLBs.

The ability of PaLEC1 and PaBBM to induce somatic embryogenesis was verified in Arabidopsis. Expression of the PaBBM and PaLEC1 proteins was verified by western-blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Overexpression of 35S:PaBBM-eGFP or 35S:eGFP-PaLEC1/35S:PaLEC1-eGFP (Fig. 5, A and B) but not the empty vector (Supplemental Fig. S5, B and C) caused ectopic production of cotyledons from somatic tissues. The embryo-specific genes, such as OLE, COLEOSIN, CRUCIFERIN3 (CRU3), ABI3, and FUS3, were up-regulated in somatic embryonic culture tissues of the transgenic plants (Fig. 5, C and D). In addition, triacylglycerols, which accumulate in embryonic tissues and stained intensely with Sudan Red 7B, also were accumulated in embryonic-like tissues of 35S:PaLEC-eGFP and 35S:eGFP-PaBBM transgenic lines (Fig. 5E). Moreover, overexpression of eGFP-PaLEC1 rescued the lec1-1 desiccation-tolerant phenotype (Fig. 5E), supporting that PaLEC1 is the functional ortholog of Arabidopsis LEC1. The 35S:eGFP-PaBBM construct failed to be generated and, therefore, was omitted from this study. In short, PaLEC1 and PaBBM genes are evolutionarily conserved and capable of inducing the somatic embryonic program.

Figure 5.

PaBBM and PaLEC1 are sufficient to initiate somatic embryogenesis. A, Overexpression of PaBBM-eGFP induces embryonic culture tissue (ECT) in the wild type. B, Overexpression of eGFP-PaLEC1 induces ECT in the wild type. C, Expression of embryo-specific genes, CRU3, ABI3, and FUS3, in the ECT of PaBBM-eGFP overexpressors. D, Expression of embryo-specific genes, CRU3, ABI3, and FUS3, in the ECT of eGFP-PaLEC1 overexpressors. E, Sudan Red 7B staining indicates the accumulation of triacylglycerols in PaLEC1-eGFP and PaBBM-eGFP overexpressors. F, Overexpression of eGFP-PaLEC1 rescues the desiccation intolerance of the Arabidopsis lec1-1 mutant. Arrows indicate the complemented lec1-1 plants. Bars in A, B, and E = 500 μm.

In addition to surveying transcriptional factors that displayed an enriched expression pattern during seed development, we also examined SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE (SERK), whose expression has been shown to be associated with somatic embryogenesis (Schmidt et al., 1997; Hecht et al., 2001; Santos et al., 2005; Steiner et al., 2012). Three previously reported SERK-like genes, PaSERK1, PaSERK2, and PaSERK5 (Huang et al., 2014), also were present in our transcriptome database. However, the expression of PaSERK1, PaSERK2, and PaSERK5 was ubiquitous across the tissues we analyzed and did not display embryo-specific patterns (Table I). The lack of correlation between embryonic/somatic embryonic tissues and the expression of SERK genes has been reported in rice (Oryza sativa) and maize (Zea mays; Baudino et al., 2001; Ito et al., 2005).

Expression of PaSTM Is Associated with PLB Development

Knowing that PLB development does not follow the embryogenesis program, we were interested in genes whose functions may potentially contribute to PLB initiation and development and provide hints about pathway(s) from which the PLB is derived. To do that, TF genes under the GO category regulation of transcription, DNA-templated in PLB clusters (Supplemental Fig. S1B) were identified (Supplemental Data Set S3).

Among the PLB-enriched TFs, we were particularly interested in the class I KNOX TF PaSTM because ectopic expression of class I KNOX TFs has been reported to cause the formation of new tissue organization centers that are sufficient to induce shoots or organ-related structures (Sinha et al., 1993; Chuck et al., 1996; Williams-Carrier et al., 1997; Golz et al., 2002). PaSTM encodes a protein that shares 63% identity and 73% similarity with Arabidopsis STM. Phylogenetic analysis of class I KNOX TFs shows that PaSTM and Arabidopsis STM constitute a paired clade (Supplemental Fig. S6A). The expression level of PaSTM mRNA was correlated with the initiation of PLB, being significantly elevated at the early stage of PLBs (small) and declining but being maintained at moderate levels as development proceeded (30 d after germination; Fig. 6A). The level of PaSTM mRNA, on the other hand, was relatively low in 10- and 20-d-old protocorms and increased to a moderate level in 30-d-old protocorms. Coincidently, the expression pattern of PaSTM was positively correlated with its potential target, GIBBERELLIN 2-OXIDASE1 (PaGA2OX1; Fig. 6A). The maize STM homolog, KNOTTED1, has been shown to directly regulate GA 2-oxidase to maintain a low level of GA in shoot apical meristems (Bolduc and Hake, 2009). In addition, the accumulation of PaSTM in PLBs was positively correlated with a shoot generation marker (Che et al., 2006), PaERF1 (homologous to Arabidopsis RAP2.6L ERF/AP2 TF; Fig. 6A; Supplemental Fig. S6B), suggesting that PLBs have a shoot generation capacity. The expression of PaERF1 did not seem to be a general stress-related response, because the mRNA of PaERF2, a stress-related gene (Supplemental Fig. S6B), showed a different expression pattern. In situ hybridization further confirmed that PaSTM mRNA was evenly distributed in newly emerging and small PLBs but was undetectable in highly vacuolated callus cells (Fig. 6B). In developing protocorms, on the other hand, PaSTM mRNA was restricted to the anterior end where shoots initiate (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results showed that the expression of PaSTM mRNA is tightly associated with the initiation of PLBs.

Figure 6.

Expression of PaSTM mRNA is associated with PLB initiation. A, Expression patterns of the indicated genes enriched in developing PLBs and/or protocorms. B, Morphology of an explant, newly emerging PLBs (PLBN), and small PLBs (PLBS). In situ hybridization was performed with an antisense PaSTM on longitudinal sections through the center of PLBN and PLBS. Asterisks indicate individual PLBs. ca, Callus tissues from which PLBs are derived. C, In situ hybridization with an antisense PaSTM on longitudinal sections through the center of protocorms. PaSTM-AS, Antisense probe of PaSTM; PaSTM-S, sense probe of PaSTM used as a negative control. D, Expression patterns of the indicated genes in callus, developing PLBs, and interior ovary tissues collected at 160 DAP. PLBS, medium PLBs (PLBM), large PLBs (PLBL), 10-d-old protocorms (protocorm10), 20-d-old protocorms (protocorm20), and 30-d-old protocorms (protocorm30) are indicated. Bars in B and C = 200 μm.

To exclude the possibility of the involvement of PaLEC1 and PaFUS3 during PLB initiation, the expression of PaLEC1 and PaFUS3 also was examined in newly emerging PLBs. Unlike high levels of PaLEC1 and PaFUS3 mRNAs detected in embryonic tissues at 160 DAP, PaLEC1 and PaFUS3 mRNAs were almost undetectable in developing PLBs, including newly emerging PLBs (Fig. 6D). This result confirms that the expression of PaLEC1 and PaFUS3 is not associated with PLB initiation. The preferential expression of PaSTM in newly emerging PLBs was validated by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 6D). WUSCHEL (WUS) is reported to act as a positive regulator of shoot stem cell fate (Gordon et al., 2007; Duclercq et al., 2011). Phalaenopsis WUSCHEL (PaWUS) and WUS-RELATED HOMEOBOX (PaWOX) genes were identified from our transcriptome database (Supplemental Fig. S6C). However, PaWUS and PaWOX mRNAs were not up-regulated in PLBs (Table I). It is possible that the expression of PaWUS is restricted to a defined area of PLB meristem, and its potential role in PLB development remains to be determined.

To test the ability of PaSTM to induce PLB-like organogenesis, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing PaSTM or its fusion to GFP (GFP-PaSTM or PaSTM-GFP). Expression of the PaSTM proteins was confirmed by immunoblot (Fig. 7A). Compared with the transgenic plant carrying the empty vector (Fig. 7B), most of the T1 transgenic plants overexpressing PaSTM grew very slowly and had severe developmental defects. Among the 237 T1 transformants we recovered, most displayed aborted normal postembryogenic development and initiated unorganized cell proliferation, with 116 plants (49.4%) forming a markedly large dome-shaped structure (Fig. 7C) and 101 plants (43%) forming a brush-like disorganized structure (Fig. 7D) at the position where shoot meristems resided. The first two rosette leaves of overexpressors were severely deformed and displayed either a slender or a lobed structure (Fig. 7E). Most of these plants arrested at the seedling stage. Very few transgenic plants managed to make a few more leaves and bolted approximately 35 to 37 d after germination (Fig. 7F). The rest of the other transgenic lines (7.6%) grew like wild-type plants. To exclude the potential influence of antibiotics on transgenic plants overexpressing PaSTM, T1 transgenic plants that were kept off antibiotics 10 d after germination were examined. Phenotypes similar to those of transgenic plants kept on the antibiotics were observed (Supplemental Fig. S7A). Homozygous T2 lines from wild-type-looking 35:GFP-PaSTM overexpressors were recovered for further analysis. Unlike their heterozygous counterparts, leaf blades of cauline and rosette leaves of homozygous lines appeared to be curved and lobed and petioles were shortened (Fig. 7G), similar to previous reports on transgenic plants overexpressing class I KNOX TFs (Chuck et al., 1996; Sakamoto et al., 1999; Ori et al., 2000). However, we did not observe ectopic meristems from PaSTM overexpressors, probably because of the structural divergence of STM between Phalaenopsis spp. orchids and Arabidopsis. Similar to 35S:PaSTM transgenic lines, 35:GFP-PaSTM overexpressors displayed large dome-shaped or brush-like shoot apical meristems (Supplemental Fig. S7B). A less severe phenotype was observed in 35S:PaSTM-GFP overexpressors (Supplemental Fig. S7C). None of the described phenotypes were observed in vector-only control plants (Supplemental Fig. S7D).

Figure 7.

Overexpression of PaSTM is able to induce a shoot regeneration program. A, Overexpression of PaSTM was confirmed by immunoblotting using a PaSTM-specific polyclonal antibody. The arrow indicates the full-length PaSTM protein. Degraded PaSTM protein is marked by the asterisk. Protein loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining. B, Transgenic plant carrying the pK2GW7 vector. E to F, Overexpression of PaSTM causes the formation of dome-shaped (C) or brush-like (D) shoot meristems, lobed leaves (E), and early-bolting phenotypes (F). Red arrowheads indicate unorganized meristems. DAG, Days after germination. Bars = 0.5 mm. G, Cauline and rosette leaves of homozygous lines overexpressing PaSTM appeared to be curved and lobed. het, Heterozygous line; homo, homozygous line; wt, wild-type line. Bars = 1 cm. H, Transcript levels of RAP2.6L (At5g13330) and GA2OX2 (At1g30040) in wild-type and transgenic plants overexpressing PaSTM or carrying the empty pK2GW7 vector (V). STM (A), PaSTM overexpressors with abnormal seedlings; STM (N), PaSTM overexpressors with normal seedlings.

The shoot regeneration capacity of the unorganized structures of PaSTM overexpressors was monitored by the expression of the shoot regeneration markers RAP2.6L and GA2OX2 (Che et al., 2006). As shown in Figure 7H, mRNAs of these markers were increased in abundance in PaSTM overexpressors but not in the wild-type or transgenic plants carrying the empty vector. Additionally, the RAP2.6L mRNA level was positively correlated with the severity of abnormality of PaSTM overexpressors. Taken together, we propose that PaSTM may be an important factor for PLB generation.

DISCUSSION

Transcriptome Dynamics of Pollination-Triggered Reproductive Development

Here, we profiled temporal transcriptome dynamics in developing ovaries as development progressed from ovule to embryo development. The data revealed that distinct cellular functions were associated with different stages of the Phalaenopsis spp. reproductive program. Cell division-related gene activities were overrepresented at the early stage of ovary development, during which ovules and pollen tubes were developing. This is consistent with our previous finding that the selected core cell cycle genes are expressed preferentially in ovaries transitioned from gametophyte development to embryogenesis (Lin et al., 2014). In addition, TFs such as AG-, ANT-, BEL1-, CUC-, SEP-, and SPT-like genes shown previously to regulate carpel and ovule development in Arabidopsis were enriched in ovary tissues before transition. It has been shown that CUCs work together with SPT to control the formation of carpel marginal structures and the development of septa and ovules (Nahar et al., 2012; Galbiati et al., 2013). ANT and CUCs are important for the initiation of the ovule primordium (Ishida et al., 2000; Galbiati et al., 2013). BEL1 is important to control integument identity and works together with AG and SEP to regulate ovule development (Modrusan et al., 1994; Ray et al., 1994; Reiser et al., 1995; Brambilla et al., 2007). Ovule fate is further maintained by members of the MADS box family of TFs, SHP1, SHP2, STK, and AG (Favaro et al., 2003; Pinyopich et al., 2003). Taken together, our results indicate that ovule development of Phalaenopsis spp. orchids requires similar sets of regulatory factors and is likely to be evolutionarily conserved.

RNA-seq analysis revealed that DNA methylation, RNA interference, and Met biosynthetic processes marked the stage when fertilization occurred and embryos began to develop. The epigenetic reprogramming involved in small RNA-guided methylation and DNA methylation has been reported to maintain genome integrity and epigenetic inheritance in reproductive tissues (Calarco et al., 2012; Jullien et al., 2012) and is likely to play a role during the reproductive development of Phalaenopsis spp. orchids.

As embryos started to develop and seeds began to form (90–200 DAP), seed-specific TFs, including PaLEC1, PaFUSCA3, PaABI3L1, PaABI3L2, PaBBM, and PaWRI1, were identified as overrepresented transcripts. In addition, the enrichment of GO terms associated with lipid and carbohydrate mobilization and storage at the late stage of developing ovary tissues (140–160 and 180–200 DAP) confirms the concurrent seed maturation processes (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Data Set S2). The tissue-specific localization and functional studies of PaLEC1 and PaBBM validate their roles in activating and maintaining the embryonic program. Interestingly, the major shift in gene expression between early and late seed development (Fig. 2A) indicates maturation-specific transcriptome reprogramming, which also has been reported in Arabidopsis (Belmonte et al., 2013). Interestingly, a substantial overlap in RNA populations of ovary tissues progressing from ovule development to early embryo establishment (Figs. 2A and 3A, cluster X) suggests that similar cellular processes are likely to be shared as tissues transition from gametophytic to embryonic development in Phalaenopsis spp. orchids. Taken together, global comparisons of mRNA populations suggested a coordinated temporal shift in gene expression during reproductive development in ovary tissues. Although lacking the complete organogenesis and histodifferentiaion, the maturation process of Phalaenopsis spp. orchid embryos characterized by seed-specific TFs is evolutionarily conserved.

One of the distinct features of orchid seeds is their lack of endosperms. It has been documented that triple fusion between polar nuclei and the sperm nucleus rarely occurs, and endosperm development is either aborted at a very early stage or cannot be initiated (Kull and Arditti, 2002; Batygina et al., 2003). Coincidently, transcripts of the storage proteins 2S albumin and prolamins commonly found in endosperms of monocotyledon plants (Shewry and Halford, 2002) could not be identified from our and publicly available transcriptome databases. Intriguingly, members of type I MADS box TFs, whose functions are found to be associated with endosperm development (Masiero et al., 2011), are greatly reduced in orchid genomes (Cai et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). The concurrent loss of the molecular repertoire normally associated with endosperm development may contribute to the lack of endosperm in orchid seeds.

The Regulatory Network Controlling Genes Expressed during Embryo Development Is Different from Those of the PLB and Protocorm

Our studies provide evidence to support the notion that protocorms and PLBs share similar transcriptome dynamics. Particularly, chloroplast development and functions involved in heme binding, copper binding, and the oxidation reduction process were overly active. In addition, stress-related cellular processes including the abscisic acid-activated signaling pathway and the wounding response were overrepresented. It is likely that cutting and the culture conditions activate stress responses during tissue culture practice, as suggested previously (Fehér et al., 2003; Bai et al., 2013; Gliwicka et al., 2013; Maximova et al., 2014).

Surprisingly, protocorms and PLBs (often described as somatic embryos in the literature) shared little similarity with zygotic embryonic tissues or other meristematic tissues like emerging young leaves, emerging stalk buds, and floral stalks (Fig. 2A). The lack of embryonic identity in PLBs was further supported by the lack of RNA accumulation of two embryo-specific marker genes, PaLEC1 and PaBBM. Therefore, protocorms and PLBs seem to possess a unique molecular program that is different from that of embryonic and other meristematic tissues.

Our data show that PLB and protocorm development seems to be regulated similarly but not identically. For example, PaABI3L1 mRNA was relatively abundant in protocorms but its level was low in PLBs (Fig. 3B). PaSTM, PaGA2OX1, and PaERF1 mRNAs, on the other hand, were relatively abundant in PLBs but less abundant in protocorms (Fig. 6A). Functional characterization of these genes may help in identifying gene regulatory networks unique to protocorms or PLBs.

PLBs: Organogenesis Versus Somatic Embryogenesis

Somatic embryogenesis is a defined developmental process that leads to the establishment of embryos independent of a fertilization event (von Arnold et al., 2002; Braybrook and Harada, 2008; Yang and Zhang, 2010). Similar to zygotic embryogenesis, specific molecular markers contributing to the formation of a basic body plan (morphogenesis) and the accumulation of seed storage macromolecules (maturation) are commonly used to define the somatic embryogenesis process. Despite the commonly accepted view in the orchid community that PLBs are of somatic embryonic origin, the comparative transcriptome and marker gene analyses presented here argue that the regeneration of PLBs does not follow the embryogenesis program. Instead, the tight correlation between PLB development and PaSTM expression suggests that the PaSTM-mediated shoot organogenesis pathway may be important for PLB initiation.

The expression of STM has been reported to be associated with organogenic shoot formation of Kalanchoë daigremontiana, Agave tequilana, and dodder (Cuscuta pentagona; Garcês et al., 2007; Abraham-Juárez et al., 2010; Alakonya et al., 2012). Up-regulation of the STM gene also is associated with the de novo assembly of shoot apical meristems from cultured explants (Gordon et al., 2007; Atta et al., 2009). Similarly, de novo leaf initiation of river weeds that lack typical shoot apical meristems is tightly linked to the expression of the STM gene (Katayama et al., 2010). The positive role of class I KNOX genes in meristem cell fate is further supported by the gain-of-function approach. In these cases, ectopic expression of the class I KNOX genes has been found to cause the formation of new tissue organization centers that are sufficient to induce ectopic shoots or organ-related structures (Sinha et al., 1993; Müller et al., 1995; Chuck et al., 1996; Williams-Carrier et al., 1997; Brand et al., 2002; Golz et al., 2002; Lenhard et al., 2002). Consistently, PaSTM is able to increase shoot generation ability by promoting the expansion of shoot apical meristems and/or inducing organ-related structures with concurrent up-regulation of shoot regeneration makers, such as RAP2.6L and GA2OX2, when overexpressed in Arabidopsis. Based on these findings, we propose that PaSTM may be an important factor for PLB regeneration.

During de novo organogenesis, the initiation of cell division, establishment of auxin maxima, and specification of founder cells are commonly observed before organ development (Pernisová et al., 2009; Perianez-Rodriguez et al., 2014). In addition, the coordinated interaction of phytohormones such as auxin, cytokinin, and GAs is known to regulate a battery of genes required for the acquisition of competence and/or the organization of the shoot apical meristem (Benková et al., 2003; Gordon et al., 2009; Pernisová et al., 2009; De Smet et al., 2010; Marhavý et al., 2011, 2014; Schuster et al., 2014). It is likely that similar signaling and gene regulatory activities are important in setting up PLB regeneration. In fact, the expression of PaGA2OX1, a GA-catabolizing enzyme, was associated with PLB development. This is consistent with previous reports that GA inactivation is required for the activity of the shoot apical meristem (Sakamoto et al., 2001; Jasinski et al., 2005; Bolduc and Hake, 2009). Additionally, several auxin-responsive genes were found to be up-regulated in PLB tissues (Supplemental Data Set S1). It will be of future interest to understand how phytohormone signaling is integrated with the transcription network to coordinate the initiation and development of PLBs.

Unlike the de novo organogenesis commonly observed in other plant species, where organs such as shoots or roots are directly generated from callus-derived meristematic tissues (Duclercq et al., 2011), wound-induced callus tissues of Phalaenopsis spp. orchids often if not entirely take the PLB route before subsequent shoot regeneration (Ernst, 1994). This raises the question of whether PLB is a specialized form of organ with shoot meristem development. If this is the case, what are the unique factors that contribute to PLB regeneration, and how are they different from those for direct shoot regeneration? The comprehensive transcriptome catalog of developing PLBs presented here provides a valuable resource and may help in identifying key genes to address these questions.

In summary, in this study, we profiled the genome-wide transcriptome of reproductive development in P. aphrodite. The temporal and spatial integration of transcriptomic dynamics in reproductive tissues at different developmental stages provides valuable insights into the gene regulatory programs that characterize the reproductive processes of Phalaenopsis spp. orchids. In addition, our findings uncover a previously unrecognized tissue identity of PLBs. Furthermore, we propose that the regeneration program of PLBs is likely derived from a PaSTM-dependent regeneration process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Phalaenopsis aphrodite ssp. formosana (m1663) seedlings in 2.5- or 3-inch pots were purchased from Chain Port Orchid Nursery. Plants were grown in a growth chamber with alternating 12-h-light (23°C)/12-h-dark (18°C) cycles. Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Columbia ecotype was grown at 22°C under 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycles in a growth chamber. The lec1-1 mutant (Lotan et al., 1998) was purchased from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (http://www.arabidopsis.org).

Induction of PLBs

Mature seeds were allowed to germinate on one-quarter-strength Murashige and Skoog basal medium supplemented with 0.1% (w/v) tryptone, 1.8% (w/v) Suc, 2% (w/v) potato homogenate, 0.00001% (w/v) thiamine-HCl, 0.00001% (w/v) pyridoxine-HCl, 0.0001% (w/v) nicotinic acid, 0.01% (w/v) myoinositol, and 1% (w/v) agar, adjusted to pH 5.7. Fifty-five to 80 d after germination, protocorms grown to approximately 3 mm in diameter were excised to remove the tip and bottom portions. The protocorm segments were transferred to PLB-inducing medium containing 0.1% (w/v) tryptone, 2% (w/v) Suc, 2% (w/v) potato homogenate, 2.5% (w/v) banana homogenate, 0.01% (v/v) citric acid, 0.1% (w/v) charcoal, and 1% (w/v) agar, adjusted to pH 5.5 to induce primary PLBs. Primary PLBs were then used to induce secondary PLBs by cutting to remove the tip and bottom portions. The PLB segments were then moved to PLB-inducing medium as described above. Secondary PLBs were used for the experiments described below. Cultures were maintained at 25°C under 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycles under illumination at 45 to 55 μmol photons m−2 s−1 in a growth chamber. A thin layer of callus tissue formed on the cutting surface of explants before the appearance of emerging PLBs (Fig. 5B).

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

Orchid flowers were hand pollinated, and developing ovaries were harvested at the specified day. For reproductive tissues, only the interior tissues of developing capsules were scooped and pooled for RNA extraction (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1). Because PLBs did not grow at a synchronized rate, the size and developmental stage of PLB samples were categorized and collected separately (Fig. 1B). Protocorms that germinated after 10, 20, and 30 d were collected and categorized (Fig. 1C). Because germination rate varied in different batches of capsules, only healthy-looking protocorms (light-green in color and larger than the ones that failed to develop) were individually collected for the experiments. Young leaves, emerging stalk buds, or root tips with sizes smaller than 2 cm in length, 5- to 10-cm-long floral stalks, and floral buds less than 5 mm were collected for RNA extraction. The tissue samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in a freezer at −80°C. RNA was isolated using OmicZol RNA Plus extraction reagent (Omics Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen) followed by RNeasy mini-column purification according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen).

Transcriptome Assembly and RNA-Seq

RNA samples extracted from different tissues, including interior tissues of developing capsules (30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 120, 140, 140, 160, 180, and 200 DAP), protocorms, PLBs, young leaves, emerging stalk buds, floral stalks, floral buds, and root tips, were pooled together for transcriptome sequencing. The paired-end cDNA library was synthesized and amplified using the TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit (version 2) following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). The cDNA library was sequenced by Genome HiSeq2000 (Illumina) according to the supplier’s protocols (Welgene). The raw sequencing data were filtered to remove low-quality (quality value ≥ 20), adaptor, and repeat sequences (Smeds and Künstner, 2011). Qualified reads were de novo assembled by the Trinity program (Grabherr et al., 2011). The resulting sequences and paired-end information were connected and incorporated by SSPACE Basic version 2 (Boetzer et al., 2011) and extended by TGICL (Pertea et al., 2003) to generate unigenes. The estimation of unigene abundance was calculated by RSEM (Li and Dewey, 2011). RSEM computes maximum likelihood abundance estimates and posterior mean estimates and calculates 95% credibility intervals for each gene and isoform. Unigenes that have at least one expected count and an effective length of 200 nucleotides or more were included in the transcriptome assembly. The assembled 12-Gb sequence reads yielded 112,467 unigenes. Raw sequenced reads and nucleotide assembled unigenes were deposited in the GenBank database (SRA261547 and GENW01000000).

Additional approximately 10-Mb, 50-bp single-end reads from interior tissues of developing capsules (30–40, 50–60, 70–80, 90–120, 140–160, and 180–200 DAP), protocorms, PLBs, young leaves, emerging stalk buds, and floral stalks were sequenced separately by Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina). The RNA reads were mapped to the assembled transcriptome using the short-read alignment software Bowtie 2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). The relative abundances of the transcripts were quantified by Cufflinks2 (Trapnell et al., 2012). Between 84% and 90% of RNA reads derived from sampled tissues were able to be mapped back to the assembled transcriptome (Supplemental Table S2). The gene expression levels were calculated as FPKM.

Functional Annotation of the Assembled Unigenes

The assembled unigenes were searched against the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant protein database using the alignment algorithm RAPSearch2 (Zhao et al., 2012) with a cutoff E value ≤ −3. The top alignment hits were used to predict the sequence orientation and GO accessions of the unigenes.

Data Analysis and Coexpression Clustering

Principal component analyses were performed using GeneSpring12.6.1 software. To reduce the false-positive result caused by low-abundance transcripts and generate robust groups of coregulated genes, transcripts with an FPKM value larger than or equal to 5 in at least one tissue and that showed a 10-fold difference in at least two different tissues were selected for clustering. The identification of coregulated mRNAs was performed using MultiExperiment Viewer software (Howe et al., 2011). K-mean support using Pearson’s correlation was used to separate 10,893 assembled transcripts into 12 clusters (groups of coregulated genes). Gene lists derived from K-mean clusters were analyzed for GO term enrichment. The cumulative probability (P value) of hypergeometric distribution was calculated to evaluate the significance of the GO enrichment from each K-mean cluster (Chien et al., 2015). TFs falling into the designated clusters were manually selected and verified by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic Tree Construction

Protein Sequences Were Aligned by ClustalW

The resulting alignments were used to construct phylogenetic trees using MEGA 5.2.2 (Tamura et al., 2011). The maximum-likelihood method was used to generate phylogenetic trees, and 1,000 replicates were used for bootstrapping. Only bootstrap values of 50% or higher were shown for each clade. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method, and the rate variation among sites was modeled with a γ-distribution.

Plasmid Construction and Arabidopsis Transformation

Total RNA was isolated as described previously (Lin et al., 2014). Five micrograms of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis. LEC1 cDNAs from various plant species (maize [Zea mays], AF410176; rice [Oryza sativa], AY264284; soybean [Glycine max], BD242763; Arabidopsis, NM_102046; and Brassica napa, EU371726) were aligned. The evolutionarily conserved region of cDNA was used to design primer 5′-CACGCCAAGATCTCGGACGAC-3′ RACE-PCR to isolate PaLEC1 cDNA. 3′ RACE-PCR was carried out using the SMARTer RACE cDNA amplification kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech). The amplified PaLEC1 cDNA was verified by sequencing. A new primer, 5′-TCAAGGAAGCTAAACATGCAA-3′, derived from the sequenced PaLEC1 cDNA was designed for 5′ RACE-PCR (SMARTer RACE cDNA amplification kit; Clontech). The full-length cDNA of PaLEC1 was BP recombined into pDONR221 vector to make pDONR_PaLEC1. pDONR_PaLEC1 was then LR recombined with pK7WGF2 or pH7FWG2.0 (Karimi et al., 2002) to make 35SCaMV:PaLEC1-eGFP or 35SCaMV:eGFP-PaLEC1, respectively. Similarly, the full-length cDNA of PaSTM was PCR amplified and BP recombined into pDONR221 vector to make pDONR_PaSTM. pDONR_PaSTM was then LR recombined with pK2GW7.0, pK7WGF2.0, or pH7FWG2.0 to make 35SCaMV:PaSTM, 35SCaMV:eGFP-PaSTM, or 35SCaMV:PaSTM-eGFP, respectively. For the PaBBM gene, the full-length cDNA of PaBBM was PCR amplified, digested by XbaI and SalI, and cloned into a modified version of the pDONR221 vector (the ccdB gene was replaced by multiple cloning sites from NotI to KpnI of the pBluescript vector) to make pDONR_PaBBM. pDONR_PaBBM was then LR recombined with pH7FWG2.0 to make the 35SCaMV:PaBBM-eGFP construct.

The resulting plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The wild-type strain (Wassilewskija ecotype) was transformed by A. tumefaciens GV3101 using the floral dipping method (Clough and Bent, 1998). In addition to antibiotic selection, the transformants were further verified by PCR amplification of a 207-bp DNA fragment using forward primer 5′-CACGCCAAGATCTCGGACGAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CTCACGGTATCGGTGGAGAT-3′ for PaLEC1; a 525-bp DNA fragment using forward primer 5′-GGAGGAGAGGATCCAGCTTT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AAACTGCATCTCCTCCGATG-3′ for PaSTM; and a 279-bp DNA fragment using forward primer 5′-TGTTGGAGAATGAGGGGAAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ATAAGCCCTTGCTGCCTTTT-3′ for PaBBM. For the complementation test of PaLEC1, 35SCaMV:PaLEC1-eGFP or 35SCaMV:eGFP-PaLEC1 was transformed into the lec1-1 mutant (Lotan et al., 1998).

qRT-PCR

DNA-free RNA was reverse transcribed in the presence of a mixture of oligo(dT) and random primers (9:1 ratio) using the GoScript Reverse Transcription System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten microliters of reverse transcription-PCR reaction contained 2.5 μL of 1:20 diluted cDNA, 0.2 μm of primers, and 5 μL of 2× KAPA SYBR FAST master mix (KAPA Biosystems). The following program was used for amplification: 95°C for 1 min, and 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 s and 58°C to 62°C for 20 s. PCR was performed in triplicate, and the experiments were repeated with RNA isolated from two independent samples. Primer pairs and the specified annealing temperature used for quantitative PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S4. UBIQUITIN was used as an internal control (Lin et al., 2014).

In Situ Hybridization

Protocorms and PLB samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, 4% DMSO, 0.25% glutaraldehyde, 0.1% Tween 20, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water at 4°C overnight. Tissues were then dehydrated and infiltrated with Paraplast (Leica) using a KOS Rapid Microwave Labstation (Milestone). Tissues (10 μm thick) were sectioned using a MICROM 315R microtome (Thermo Scientific) and mounted onto a poly-l-Lys-coated slide (Matsunami). Sections were then deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol, and digested with 2 mg mL−1 proteinase K at 37°C for 30 min. In situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Lin et al., 2014) with hybridization temperature optimized for each gene: 62°C for PaBBM, 51.5°C for PaLEC1, and 60°C for PaSTM. Tissue sections and in situ hybridization were photographed with a Zeiss Axio Scope A1 microscope equipped with an AxioCam HRc camera (Zeiss).

Sudan Red 7B Staining

Sudan Red staining has been described in detail (Harding et al., 2003). Briefly, tissues were incubated in 70% (v/v) ethanol overnight to remove chlorophyll before staining. Tissues were stained in 0.1% (w/v) Sudan Red 7B (Sigma) solution for 1 h at room temperature, rinsed several times in water, and then mounted in glycerol for examination with an SMZ800 stereoscopic zoom microscope (Nikon).

PaSTM Antibody Production

Specific antibody for PaSTM was generated in rabbits against a peptide region (LHFHPRSKMENWSGGNNP) unique to PaSTM. This peptide was conjugated to ovalbumin via a Cys residue and injected into rabbits according to the supplier’s protocols (LTK BioLaboratories). The resulting antibody was affinity purified by column chromatography using PaSTM peptide.

Protein Isolation and Immunoblot Analysis

Approximately 0.1 g of tissues was homogenized in 1 mL of RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA, 0.25% [w/v] deoxycholate, 0.1% [w/v] SDS, and 1% [v/v] Nonidet P-40) or 1 mL of urea buffer (250 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 3.5% [w/v] SDS, 1 m urea, and 10% [v/v] glycerol) supplemented with 1 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), and 10 μm MG132 (Sigma). Homogenized protein extracts were centrifuged at 16,000g at 4°C for 5 min to remove cell debris. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by the DC Protein Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad). Approximately 50 μg (PaLEC1 and PaBBM) or 100 μg (PaSTM) of protein was resolved on a Bolt 4% to 12% or 10% Bis-Tris Plus gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). Blots were blocked in 5% (w/v) milk in Tris-buffered saline solution with 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. A 1:2,000 dilution of the GFP antibody (Roche) or purified PaSTM specific antibody was used as the primary antibody. A 1:20,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was used as the secondary antibody. The peroxidase activity was detected by a chemiluminescence assay (Advansta).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank data libraries under accession numbers SRA261547 and GENW01000000.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Images of interior tissues of developing ovules harvested at different stages for RNA-seq and K-mean clustering identified 12 groups of genes associated with specific developmental stages.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phylogenetic relationship of MADS, AP2, HD-Zip, and B3 domain TFs.

Supplemental Figure S3. Protein sequence alignment of LEC1 and BBM proteins.

Supplemental Figure S4. Unrooted maximum-likelihood trees of the 7S and 11/12S albumins.

Supplemental Figure S5. Confirmation of PaLEC1-eGFP and PaBBM-eGFP proteins in overexpressor lines.

Supplemental Figure S6. Phylogenetic relationship of class I KNOX, AP2/ERF, and WUS/WOX TFs.

Supplemental Figure S7. Overexpression of PaSTM causes abnormal meristems.

Supplemental Table S1. Statistics of the de novo transcriptome assembly.

Supplemental Table S2. Statistics of RNA-seq reads.

Supplemental Table S3. Statistics of 12 gene clusters in Supplemental Figure S1B.

Supplemental Table S4. List of primer pairs used for qRT-PCR.

Supplemental Data Set S1. Comparative transcript abundances of preferentially regulated genes in reproductive tissues of P. aphrodite by RNA-seq analysis.

Supplemental Data Set S2. GO analysis of tissue-specific K-mean clusters.

Supplemental Data Set S3. Comparative transcript abundances of preferentially regulated TFs in reproductive tissues of P. aphrodite by RNA-seq analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Donna Fernandez for providing the Arabidopsis seeds; Dr. Swee-Suak Ko, Yi-Chen Lien, and Hue-Ting Yang for assistance with in situ hybridization; Chi-Nga Chow and Dr. Wen-Chi Chang for assistance with GO analysis and comments on the article; Cheng-Pu Wu for database maintenance; the AS-BCST Greenhouse Core Facility for greenhouse service; and Miranda Loney for English editing.

Glossary

- PLB

protocorm-like body

- DAP

days after pollination

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads

- GO

Gene Ontology

- TF

transcription factor

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Development Program of Industrialization for Agricultural Biotechnology (to S.-C.F.) and by the Biotechnology Center in Southern Taiwan, Academia Sinica (to S.-C.F.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Abraham-Juárez MJ, Martínez-Hernández A, Leyva-González MA, Herrera-Estrella L, Simpson J (2010) Class I KNOX genes are associated with organogenesis during bulbil formation in Agave tequilana. J Exp Bot 61: 4055–4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alakonya A, Kumar R, Koenig D, Kimura S, Townsley B, Runo S, Garces HM, Kang J, Yanez A, David-Schwartz R, et al. (2012) Interspecific RNA interference of SHOOT MERISTEMLESS-like disrupts Cuscuta pentagona plant parasitism. Plant Cell 24: 3153–3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditti J. (1992) Fundamentals of Orchid Biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- Atta R, Laurens L, Boucheron-Dubuisson E, Guivarc’h A, Carnero E, Giraudat-Pautot V, Rech P, Chriqui D (2009) Pluripotency of Arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro. Plant J 57: 626–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai B, Su YH, Yuan J, Zhang XS (2013) Induction of somatic embryos in Arabidopsis requires local YUCCA expression mediated by the down-regulation of ethylene biosynthesis. Mol Plant 6: 1247–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batygina TB, Bragina EA, Vasilyeva VE (2003) The reproductive system and germination in orchids. Acta Biol Cracov Ser Bot 45: 21–34 [Google Scholar]

- Baudino S, Hansen S, Brettschneider R, Hecht VF, Dresselhaus T, Lörz H, Dumas C, Rogowsky PM (2001) Molecular characterisation of two novel maize LRR receptor-like kinases, which belong to the SERK gene family. Planta 213: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum AA, Tamaki M, Tahara M, Kako S (1994) Somatic embryogenesis in Cymbidium through in-vitro culture of inner tissue of protocorm-like bodies. J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci 63: 419–427 [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte MF, Kirkbride RC, Stone SL, Pelletier JM, Bui AQ, Yeung EC, Hashimoto M, Fei J, Harada CM, Munoz MD, et al. (2013) Comprehensive developmental profiles of gene activity in regions and subregions of the Arabidopsis seed. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: E435–E444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benková E, Michniewicz M, Sauer M, Teichmann T, Seifertová D, Jürgens G, Friml J (2003) Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell 115: 591–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentsink L, Koornneef M (2008) Seed dormancy and germination. The Arabidopsis Book 6: e0119, doi/10.1199/tab.0119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W (2011) Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 27: 578–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolduc N, Hake S (2009) The maize transcription factor KNOTTED1 directly regulates the gibberellin catabolism gene ga2ox1. Plant Cell 21: 1647–1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla V, Battaglia R, Colombo M, Masiero S, Bencivenga S, Kater MM, Colombo L (2007) Genetic and molecular interactions between BELL1 and MADS box factors support ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2544–2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand U, Grünewald M, Hobe M, Simon R (2002) Regulation of CLV3 expression by two homeobox genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 129: 565–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braybrook SA, Harada JJ (2008) LECs go crazy in embryo development. Trends Plant Sci 13: 624–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger WC. (1998) The question of cotyledon homology in angiosperms. Bot Rev 64: 356–371 [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Liu X, Vanneste K, Proost S, Tsai WC, Liu KW, Chen LJ, He Y, Xu Q, Bian C, et al. (2015) The genome sequence of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris. Nat Genet 47: 65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarco JP, Borges F, Donoghue MT, Van Ex F, Jullien PE, Lopes T, Gardner R, Berger F, Feijó JA, Becker JD, et al. (2012) Reprogramming of DNA methylation in pollen guides epigenetic inheritance via small RNA. Cell 151: 194–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernac A, Benning C (2004) WRINKLED1 encodes an AP2/EREB domain protein involved in the control of storage compound biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J 40: 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Chang WC (1998) Plant regeneration from callus culture of Cymbidium ensifolium var. misericors. Plant Cell Rep 17: 251–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P, Lall S, Nettleton D, Howell SH (2006) Gene expression programs during shoot, root, and callus development in Arabidopsis tissue culture. Plant Physiol 141: 620–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chang W (2006) Direct somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration from leaf explants of Phalaenopsis amabilis. Biol Plant 50: 169–173 [Google Scholar]

- Chien CH, Chow CN, Wu NY, Chiang-Hsieh YF, Hou PF, Chang WC (2015) EXPath: a database of comparative expression analysis inferring metabolic pathways for plants. BMC Genomics (Suppl 2) 16: S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuck G, Lincoln C, Hake S (1996) KNAT1 induces lobed leaves with ectopic meristems when overexpressed in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 8: 1277–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh S, Guha S, Rao IU (2009) Micropropagation of orchids: a review on the potential of different explants. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 122: 507–520 [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet I, Lau S, Voss U, Vanneste S, Benjamins R, Rademacher EH, Schlereth A, De Rybel B, Vassileva V, Grunewald W, et al. (2010) Bimodular auxin response controls organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 2705–2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler RL. (1993) Phylogeny and Classification of the Orchid Family. Dioscorides Press, Portland, OR [Google Scholar]

- Duclercq J, Sangwan-Norreel B, Catterou M, Sangwan RS (2011) De novo shoot organogenesis: from art to science. Trends Plant Sci 16: 597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RC, Betzner AS, Huttner E, Oakes MP, Tucker WQ, Gerentes D, Perez P, Smyth DR (1996) AINTEGUMENTA, an APETALA2-like gene of Arabidopsis with pleiotropic roles in ovule development and floral organ growth. Plant Cell 8: 155–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst R. (1994) Effects of thidiazuron on in-vitro propagation of Phalaenopsis and Doritaenopsis (Orchidaceae). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 39: 273–275 [Google Scholar]

- Favaro R, Pinyopich A, Battaglia R, Kooiker M, Borghi L, Ditta G, Yanofsky MF, Kater MM, Colombo L (2003) MADS-box protein complexes control carpel and ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15: 2603–2611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehér A, Pasternak TP, Dudits D (2003) Transition of somatic plant cells to an embryogenic state. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 74: 201–228 [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R, Gampala SS, Lynch TJ, Thomas TL, Rock CD (2005) Redundant and distinct functions of the ABA response loci ABA-INSENSITIVE (ABI)5 and ABRE-BINDING FACTOR (ABF)3. Plant Mol Biol 59: 253–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein RR, Somerville CR (1990) Three classes of abscisic acid (ABA)-insensitive mutations of Arabidopsis define genes that control overlapping subsets of ABA responses. Plant Physiol 94: 1172–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbiati F, Sinha Roy D, Simonini S, Cucinotta M, Ceccato L, Cuesta C, Simaskova M, Benkova E, Kamiuchi Y, Aida M, et al. (2013) An integrative model of the control of ovule primordia formation. Plant J 76: 446–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcês HM, Champagne CE, Townsley BT, Park S, Malhó R, Pedroso MC, Harada JJ, Sinha NR (2007) Evolution of asexual reproduction in leaves of the genus Kalanchoë. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15578–15583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzarrini S, Tsuchiya Y, Lumba S, Okamoto M, McCourt P (2004) The transcription factor FUSCA3 controls developmental timing in Arabidopsis through the hormones gibberellin and abscisic acid. Dev Cell 7: 373–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliwicka M, Nowak K, Balazadeh S, Mueller-Roeber B, Gaj MD (2013) Extensive modulation of the transcription factor transcriptome during somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 8: e69261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golz JF, Keck EJ, Hudson A (2002) Spontaneous mutations in KNOX genes give rise to a novel floral structure in Antirrhinum. Curr Biol 12: 515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SP, Chickarmane VS, Ohno C, Meyerowitz EM (2009) Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 16529–16534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SP, Heisler MG, Reddy GV, Ohno C, Das P, Meyerowitz EM (2007) Pattern formation during de novo assembly of the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Development 134: 3539–3548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, et al. (2011) Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol 29: 644–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding EW, Tang W, Nichols KW, Fernandez DE, Perry SE (2003) Expression and maintenance of embryogenic potential is enhanced through constitutive expression of AGAMOUS-Like 15. Plant Physiol 133: 653–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht V, Vielle-Calzada JP, Hartog MV, Schmidt ED, Boutilier K, Grossniklaus U, de Vries SC (2001) The Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE 1 gene is expressed in developing ovules and embryos and enhances embryogenic competence in culture. Plant Physiol 127: 803–816 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong PI, Chen JT, Chang WC (2008) Plant regeneration via protocorm-like body formation and shoot multiplication from seed-derived callus of a maudiae type slipper orchid. Acta Physiol Plant 30: 755–759 [Google Scholar]

- Howe EA, Sinha R, Schlauch D, Quackenbush J (2011) RNA-Seq analysis in MeV. Bioinformatics 27: 3209–3210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh K, Huang AH (2004) Endoplasmic reticulum, oleosins, and oils in seeds and tapetum cells. Plant Physiol 136: 3427–3434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YW, Tsai YJ, Chen FC (2014) Characterization and expression analysis of somatic embryogenesis receptor-like kinase genes from Phalaenopsis. Genet Mol Res 13: 10690–10703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Aida M, Takada S, Tasaka M (2000) Involvement of CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes in gynoecium and ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 41: 60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Takamura T, Goi M, Tanaka M (1998) Callus induction and somatic embryogenesis of Phalaenopsis. Plant Cell Rep 17: 446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Takaya K, Kurata N (2005) Expression of SERK family receptor-like protein kinase genes in rice. Biochim Biophys Acta 1730: 253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski S, Piazza P, Craft J, Hay A, Woolley L, Rieu I, Phillips A, Hedden P, Tsiantis M (2005) KNOX action in Arabidopsis is mediated by coordinate regulation of cytokinin and gibberellin activities. Curr Biol 15: 1560–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Volny M, Lukowitz W (2012) Axis formation in Arabidopsis: transcription factors tell their side of the story. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 4–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Tisserat B (1990) Clonal propagation of orchids. Methods Mol Biol 6: 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]