Abstract

Background and aims

There are limited data on the significance of liver stiffness measurements (LSM) by transient elastography in the upper extreme end of the measurable spectrum. This multicentre retrospective observational study evaluated the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients with LSM ≥20 kPa.

Methods

432 cirrhosis patients with LSM ≥20 kPa between June 2007 and October 2015 were retrospectively followed-up through electronic records.

Results

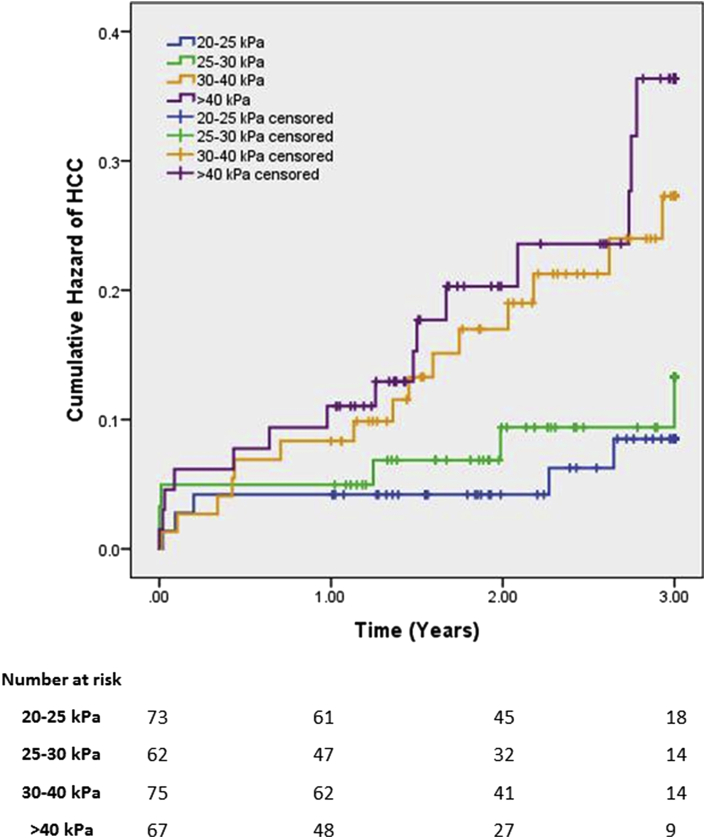

A minimum 1-year follow-up was available for 278 patients (177 men; average age 57, range 18–84). LSM ranged from 20.0 to 75.0 kPa (mean 34.6 kPa). Cumulative incidences of HCC were 19 (6.8%), 30 (10.8%) and 41 (14.7%) at 1, 2 and 3 years, respectively. HCC was associated with age (p = 0.003), higher LSM (p = 0.005) and viral aetiology (p = 0.007). Patients were divided into 4 groups based on LSM at entry: 20–25 kPa (n = 74); 25–30 kPa (n = 62); 30–40 kPa (n = 75); >40 kPa (n = 67). Compared to the 20–25 kPa group, the 30–40 kPa group had a hazard ratio (HR) of 3.0 (95% CI, 1.1–8.3; p = 0.037), and the >40 kPa group had a HR of 4.8 (95% CI, 1.7–13.4; p = 0.003).

Conclusions

This study shows an association between LSM at the upper extreme and HCC risk. Physicians may find this beneficial as a non-invasive dynamic approach to assessing HCC risk in cirrhosis patients.

List of abbreviations: LSM, liver stiffness measurement; kPa, kilopascal; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CLD, chronic liver disease; ALD, alcoholic liver disease; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; IQR, interquartile range; S, small; M, medium; XL, extra-large; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

Introduction

Liver fibrosis is common to all chronic liver disease (CLD).1 With time, this progressive disruption of hepatic architecture can develop into cirrhosis, characterised by “diffuse conversion of normal liver architecture into structurally abnormal nodules”.2 Cirrhosis is also a premalignant condition for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the 3rd largest global cause of cancer mortality.3 80–90% of HCC develop on the background of cirrhosis.

An accurate quantification of the degree of fibrosis is necessary for establishing prognosis and guiding surveillance. The historical gold standard for quantifying fibrosis is liver biopsy, but its invasive nature and potential for complications4, 5 make it unpopular among patients and impractical for serial assessments of CLD. Furthermore, since histological lesions are not uniformly distributed across the liver parenchyma, this allows for large sampling error.5, 6, 7, 8, 9

The need for credible alternatives to biopsy has stimulated research into non-invasive methods of fibrosis assessment, including serum biomarkers,10 axial imaging11, 12, 13, 14 and transient elastography.15, 16, 17 FibroScan™ (Echosens, Paris, France) allows a non-invasive liver stiffness measurement (LSM) by calculating the propagation speed of an elastic sheer wave induced by the transducer, which correlates with liver stiffness (and therefore fibrosis). It is a relatively simple, highly reproducible and operator independent technique which examines an area 100 times that of a biopsy, reducing sampling bias.18

Depending on aetiology of liver disease, a LSM between 11.5 and 22.5 kPa indicates cirrhosis.19, 20, 21 Occasionally, patients have much higher FibroScan™ readings, and there are limited data available on their significance. High liver stiffness is not exclusively seen with cirrhosis, and has been linked to several pathologies22, 23, 24, 25, 26 including HCC.27 Masuzaki et al.28 showed a relationship between rising LSM and the risk of developing HCC. The study assessed a Japanese population, where the incidence of HCC is greater than in Europe,29, 30 and these results may not reflect the risk to a European population. Furthermore, the above study made no attempt to differentiate between LSM at the upper extreme of the scale, instead grouping all values ≥25 kPa together.

This multicenter retrospective observational study aimed to evaluate the risk of HCC in patients with liver stiffness ≥20 kPa. Clinicians may find this helpful in determining how best to follow-up patients with a liver stiffness far higher than the threshold for cirrhosis.

Methods

Transient elastography

Patient records of those with biopsy-proven cirrhosis from the Department of Hepatology, St Mary's Hospital, London (2008 onwards) and the Infectious Disease Department, University Hospital “Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele”, Catania (2007 onwards) were chronologically screened to identify all LSM by FibroScan™ (Echosens, Paris, France) with stiffness values of ≥20 kPa. All LSM were performed by certified staff with experience in FibroScan™ technology. Scans were performed in an outpatient setting, with a typical appointment lasting 10 min. Entries with incomplete FibroScan™ data were excluded from the study. Substandard LSM, defined by manufacturer guidelines as <10 successful attempts, a success rate of <60% (defined as the ratio of successful measurements over the total number of attempts) or an interquartile range of >30% of the median, were not considered an exclusion criteria.

Follow-up

Patients were retrospectively followed-up through imaging studies, according to the EASL guidelines for HCC surveillance.31 The first line surveillance modality was liver ultrasound, performed biannually in stable cirrhosis patients. Follow-up imaging included US with contrast, triple phase CT, or MRI with gadolinium contrast. HCC was diagnosed considering hyperattenuation in the arterial phase, with washout in the late phase. In the event of an inconclusive study and absence of further imaging, an assumption of no HCC was made. HCC was counted from the time of the first imaging study to positively identify a tumour. The minimum follow-up period was set at 12 months from the original FibroScan™ investigation, and patients were followed for a maximum of 3 years. Data inclusion was stopped (statistically censored) at the last available follow-up, death (if date known, if unknown at last known date alive, e.g. blood test on electronic record), or at 3 years after LSM.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as percentages or as mean ± standard deviation (range). Categorical variables were compared with the chi-squared test, and continuous variables compared with Independent Student's T-test (parametric) or Mann–Whitney U test (non-parametric). A two-tailed p value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Patients were divided into 4 groups based on baseline kPa value: 20–25 kPa, 25–30 kPa, 30–40 kPa, and >40 kPa. Cumulative incidence of HCC was assessed using the Kaplan Meier approach. Pairwise log rank tests compared differences in survival distributions. A Bonferroni correction was made to adjust for multiple comparisons. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of age, gender, aetiology and liver stiffness at time of entry was conducted to assess risk factors for HCC. Categorical variables were represented using dummy variables. Hazard ratios for LSM groups were calculated using the 20–25 kPa group as reference. All statistics were performed using IBM© SPSS© Statistics version 22 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Patient population

Four hundred thirty-two patients (n = 432) with LSM ≥20 kPa were identified for follow-up at the Hepatology Department of St Mary's Hospital (London, UK; n = 261) and the Infectious Disease Department of University Hospital “Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele” (Catania, Italy; n = 171) between June 2007 and October 2015 (Table 1). There were 286 men and 146 women, with an average age of 56 ± 13 (range 0–84). The predominant underlying aetiology behind their liver disease was HCV (50.7%). Population demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with high FibroScan™ values

| Feature | n = 432 |

|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 56 ± 13 (18–84) |

| Male, n (%) | 286 (66.2) |

| Aetiology (%) | |

| ALD | 35 (8.1) |

| NAFLD | 44 (10.2) |

| HBV | 27 (6.3) |

| HCV | 219 (50.7) |

| Mixed viral** | 38 (8.8) |

| Cholestatic disease | 8 (1.9) |

| Other*** | 61 (14.1) |

| Liver stiffness (kPa)* | 34.5 ± 14.6 (18–75) |

| IQR/med* | 0.21 ± 0.15 (0–1.1) |

| Success rate (%)* | 88 ± 18 (0–100) |

| Probe, n (%) | |

| S | 5 (1.1) |

| M | 356 (82.4) |

| XL | 71 (16.4) |

*Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (range).

**Includes HIV and HDV.

***Includes multiple aetiologies, non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and other non-cirrhotic aetiologies.

Abbreviations: ALD, alcoholic liver disease; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; IQR, interquartile range; S, small; M, medium; XL, extra-large.

Exclusion

Patients were excluded when follow-up data were unavailable for a minimum of 365 days after FibroScan™ (n = 154), unless a new diagnosis of HCC was made within this time. This served to allow a lead-time for HCC development. Of the 154 excluded, 3 patients died of hepatic decompensation, 3 died of non-hepatic causes, 2 underwent liver transplantation, 8 were known to have HCC at the time of FibroScan, 62 had LSM less than 1 year prior to analysis, and 72 were lost to follow-up. A total of 278 (64.3%) patients were included in the final analysis (177 men, 101 women; average age 56.6).

Follow-up

The median follow-up was 941 days (mean 812 ± 319; range 0–1095). The set maximum follow-up period was 3 years. Data inclusion was stopped between 1 and 2 years for 107 patients, between 2 and 3 years for 62 patients, and at 3 years for 109 patients. 74% of patients had biannual screening liver ultrasound as recommended by EASL guidelines.32 In this time there were 21 recorded deaths, from HCC (n = 9), hepatic decompensation (n = 2), non-hepatic (n = 3) and unknown causes (n = 7). One patient with hepatitis C cirrhosis had developed a sustained virological response during follow-up after successful triple therapy with boceprevir/pegylated-interferon-alpha/ribavirin. The remaining patients with viral hepatitis (n = 185) had on-going viraemia. During the follow-up period there were 41 cases of HCC, constituting 14.7% of the population. Cumulative totals of HCC were 19 (6.8%), 30 (10.8%) and 41 (14.7%) at 1, 2 and 3 years respectively. HCC development was associated with older age (p = 0.003), higher LSM (p = 0.005) and viral aetiology (p = 0.007), as seen in Table 2. The majority of HCC were solitary tumours (78%). There was no association between multifocal tumours and liver stiffness (p = 0.16).

Table 2.

Characteristics according to HCC development (n = 278)

| HCC +ve | HCC –ve | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 41 | 237 | |

| Age (years) | 62 ± 11 (44–82) | 56.0 ± 12 (18–84) | 0.003 |

| Male, n (%) | 30 (73.2) | 147 (62.0) | 0.171 |

| Aetiology, n (%) | 0.007 | ||

| Viral | 35 (85.4) | 151 (63.7) | |

| Non-viral | 6 (14.6) | 86 (36.3) | |

| Liver stiffness (kPa) | 40.3 ± 15.2 (20.6–75) | 33.6 ± 13.7 (18–75) | 0.005 |

| IQR/med | 0.22 ± 0.15 (0–0.64) | 0.22 ± 0.16 (0–1.1) | 0.998 |

| Success rate (%) | 81 ± 27 (0–100) | 91 ± 15 (10–100) | 0.127 |

| Probe (%) | |||

| S | 2 (4.9) | 3 (1.3) | |

| M | 34 (83.0) | 189 (79.7) | |

| XL | 5 (12.2) | 45 (19.0) |

Abbreviations: ALD, alcoholic liver disease; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IQR, interquartile range; S, small; M, medium; XL, extra-large.

Significant differences in bold.

LSM and HCC

Patients were divided into 4 groups, based on their liver stiffness: 20–25 kPa (n = 74); 25–30 kPa (n = 62); 30–40 kPa (n = 75); >40 kPa (n = 67). Group cut-offs were decided to allow similar sized populations in each group. Kaplan Meier survival analysis compared the groups for cumulative incidence of HCC (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Risk of HCC stratified by liver stiffness

Overall differences in HCC incidence were statistically significant (χ2(3) = 10.872, p = 0.012). Pairwise log rank comparisons were conducted to determine which LSM groups had significantly different survival distributions. A Bonferroni correction was made to adjust for multiple comparisons, with significance set at p = 0.0083. There was a statistically significant difference in HCC incidence between the <25 kPa vs. >40 kPa groups (χ2(3) = 8.604, p = 0.003). Differences between other groups approached significance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Log rank comparisons between survival distributions

| Stiffness (kPa) |

20–25 |

25–30 |

30–40 |

>40 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | Sig.* | χ2 | Sig.* | χ2 | Sig.* | χ2 | Sig.* | |

| 20–25 | – | – | 0.539 | 0.463 | 5.604 | 0.018 | 8.605 | 0.003 |

| 25–30 | – | – | – | – | 2.371 | 0.124 | 4.385 | 0.036 |

| 30–40 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.455 | 0.500 |

*Significance set at p = 0.0083 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Significant differences in bold.

Risk factors for HCC

Cox proportional hazard regression univariate analysis (Table 4) revealed that age, viral aetiology and liver stiffness were significant risk factors for HCC. Compared to the 20–25 kPa group, higher liver stiffness groups had increased risks of HCC, with both the 30–40 kPa and >40 kPa reaching significance.

Table 4.

Risk factors for HCC (Cox's proportional hazard model; n = 278)

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p |

| Age (per year of life) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.003 | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 0.002 |

| Gender (male) | 1.53 (0.77–3.06) | 0.227 | 1.72 (0.84–3.52) | 0.141 |

| Aetiology | ||||

| Non-viral | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Viral | 2.78 (1.17–6.61) | 0.021 | 3.55 (1.48–8.50) | 0.005 |

| Liver stiffness | 0.021 | 0.006 | ||

| 20–25 kPa | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 25–30 kPa | 1.55 (0.47–5.08) | 0.470 | 1.39 (0.42–4.60) | 0.590 |

| 30–40 kPa | 3.21 (1.16–8.82) | 0.024 | 2.98 (1.07–8.32) | 0.037 |

| >40 kPa | 4.08 (1.48–11.24) | 0.007 | 4.81 (1.73–13.35) | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, confidence interval; kPa, kilopascals.

Significant differences in bold.

In multivariate analysis (Table 4), liver stiffness was independently associated with HCC risk. Patients in the 30–40 kPa group had a hazard ratio (HR) for developing HCC of 2.98 (95% CI 1.07–8.32; p = 0.037), compared to the 20–25 kPa group. The HR in the >40 kPa group was 4.81 (95% CI 1.73–13.35; p = 0.003). The HR of the 25–30 kPa group did not reach statistical significance. Other independent risk factors were age (HR 1.05 per year of life; 95% CI, 1.02–1.08; p = 0.002) and viral aetiology (HR 3.55; 95% CI, 1.48–8.50; p = 0.005).

Discussion

The results indicate that HCC risk rises with higher LSM. From a sample of 432 people with LSM ≥20 kPa, 41 were diagnosed with HCC within 3 years of their FibroScan™. These patients had higher mean age (p = 0.003), higher mean LSM (p = 0.005) and were more likely to have a viral aetiology (p = 0.007). Survival analysis showed that cumulative HCC incidence increased with higher baseline liver stiffness. The 20–25 kPa group had the lowest HCC risk of all four groups, though only the >40 kPa group reached statistical significance after correcting for multiple comparisons. This suggests that HCC risk continues to correlate with rising liver stiffness beyond the threshold for cirrhosis. Consequently, FibroScan™ allows stratification of HCC risk in a non-invasive and simple way.

Likewise, multivariate hazards analysis showed increasing hazard ratios for HCC parallel to rising liver stiffness. Patients with LSM of 30–40 kPa had a 3.0 times higher HCC risk than patients with 20–25 kPa baseline stiffness (p = 0.037). The risk increased to 4.8 times with baseline stiffness above 40 kPa (p = 0.003). Risk calculations were done using the 20–25 kPa group as a baseline for comparison. This group is already at a high risk of developing HCC, and all risks relative should be considered very high as well.

Liver histology and axial imaging are useful tools for diagnosing cirrhosis, but they cannot reliably divide cirrhosis into categories to reflect progressive disease.2, 33, 34 FibroScan™ (Echosens, Paris, France) is routinely used across liver centres worldwide: a quick, operator independent, reproducible, non-invasive technique, with smaller sample error than biopsy. Manufacturer guidelines on LSM interpretation are clear with respect to cut-offs for cirrhosis, but there is limited help in interpreting abnormally high results. Previous research showed increasing liver stiffness is associated with HCC,21, 28, 35 but did not differentiate between values above 25 kPa.28 To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the association between liver stiffness values at the upper extreme end of the spectrum with HCC. As HCC incidence is closely associated with the degree of fibrosis, for which LSM is a validated surrogate marker, it has been proposed that the rising risk of HCC observed among our patients reflects the severity of their liver disease. This is supported by evidence showing that LSM >21 kPa predicts clinically significant portal hypertension with a 90% specificity.31

This study adds to the current body of knowledge surrounding transient elastography.

Owing to its design, our work suffers from flaws common to all retrospective studies. The heterogeneity of our population achieved through including all aetiologies of liver disease is a possible confounding factor. However, the achieved population size lends weight to the conclusions and more accurately reflects the broad spectrum of conditions in clinical practice. Our results require external validation in order to become applicable to clinical practice. Future studies may attempt prospectively to evaluate populations with a single aetiology of liver disease. However, the relatively low frequency of such LSM makes such studies costly and time consuming. EASL guidelines (2012) recommend patients at high risk of HCC to have biannual screening abdominal US scans, and patients with a detectable nodule <1 cm be rescanned every 3–4 months.32 As patients >30 kPa have significantly increased HCC risk, they may also benefit from closer monitoring.

Conclusion

This multicentre retrospective observational study shows an association between liver stiffness measurements at the upper extreme and increasing HCC risk in patients with cirrhosis. LSM by FibroScan™ allows stratification of HCC risk in a non-invasive and reliable way. Physicians may find this beneficial as a dynamic approach to monitor HCC risk.

Financial support

None.

Declaration

Manuscript not based on previous communication to society or meeting.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Tsochatzis E.A., Bosch J., Burroughs A.K. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014;383:1749–1761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony P.P., Ishak K.G., Nayak N.C., Poulsen H.E., Scheuer P.J., Sobin L.H. The morphology of cirrhosis: definition, nomenclature, and classification. Bull World Health Organ. 1977;55:521–540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Della Corte C., Aghemo A., Colombo M. Individualized hepatocellular carcinoma risk: the challenges for designing successful chemoprevention strategies. World J Gastroenterol – WJG. 2013;19:1359–1371. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i9.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janes C.H., Lindor K.D. Outcome of patients hospitalized for complications after outpatient liver biopsy. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:96–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumida Y., Nakajima A., Itoh Y. Limitations of liver biopsy and non-invasive diagnostic tests for the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol – WJG. 2014;20:475–485. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merat S., Sotoudehmanesh R., Nouraie M., Peikan-Heirati M., Sepanlou S.G., Malekzadeh R. Sampling error in histopathology findings of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a post mortem liver histology study. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:418–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratziu V., Charlotte F., Heurtier A., Gombert S., Giral P., Bruckert E., LIDO Study Group Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1898–1906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skripenova S., Trainer T.D., Krawitt E.L., Blaszyk H. Variability of grade and stage in simultaneous paired liver biopsies in patients with hepatitis C. J Clin Pathol. 2007 Mar;60:321–324. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.036020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedossa P., Dargere D., Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzpatrick E., Dhawan A. Noninvasive biomarkers in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: current status and a glimpse of the future. World J Gastroenterol – WJG. 2014;20:10851–10863. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasarathy S., Dasarathy J., Khiyami A., Joseph R., Lopez R., McCullough A.J. Validity of real time ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol. 2009;51:1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohte A.E., van Werven J.R., Bipat S., Stoker J. The diagnostic accuracy of US, CT, MRI and (1)H-MRS for the evaluation of hepatic steatosis compared with liver biopsy: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:87–97. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1905-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor-Robinson S.D. Applications of magnetic resonance spectroscopy to chronic liver disease. Clin Med. 2001;1:54–60. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.1-1-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Werven J.R., Marsman H.A., Nederveen A.J., Smits N.J., ten Kate F.J., van Gulik T.M. Assessment of hepatic steatosis in patients undergoing liver resection: comparison of US, CT, T1-weighted dual-echo MR imaging, and point-resolved 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2010;256:159–168. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abenavoli L., Corpechot C., Poupon R. Elastography in hepatology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:839–842. doi: 10.1155/2007/621489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong V.W., Vergniol J., Wong G.L., Foucher J., Chan A.W., Chermak F. Liver stiffness measurement using XL probe in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1862–1871. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Ledinghen V., Vergniol J., Foucher J., El-Hajbi F., Merrouche W., Rigalleau V. Feasibility of liver transient elastography with FibroScan using a new probe for obese patients. Liver Int. 2010;30:1043–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasso M., Tengher-Barna I., Ziol M., Miette V., Fournier C., Sandrin L. Novel controlled attenuation parameter for noninvasive assessment of steatosis using Fibroscan®: validation in chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:244–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong V.W., Vergniol J., Wong G.L., Foucher J., Chan H.L., Le Bail B. Diagnosis of fibrosis and cirrhosis using liver stiffness measurement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:454–462. doi: 10.1002/hep.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen-Khac E., Chatelain D., Tramier B., Decrombecque C., Robert B., Joly J. Assessment of asymptomatic liver fibrosis in alcoholic patients using fibroscan: prospective comparison with seven non-invasive laboratory tests. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1188–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nahon P., Kettaneh A., Tengher-Barna I., Ziol M., de Lédinghen V., Douvin C. Assessment of liver fibrosis using transient elastography in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;49:1062–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemoine M., Shimakawa Y., Njie R., Njai H.F., Nayagam S., Khalil M. Food intake increases liver stiffness measurements and hampers reliable values in patients with chronic hepatitis B and healthy controls: the PROLIFICA experience in The Gambia. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:188–196. doi: 10.1111/apt.12561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssens F., Spahr L., Rubbia-Brandt L., Giostra E., Bihl F. Hepatic amyloidosis increases liver stiffness measured by transient elastography. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2010;73:52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arena U., Vizzutti F., Corti G., Ambu S., Stasi C., Bresci S. Acute viral hepatitis increases liver stiffness values measured by transient elastography. Hepatology. 2008;47:380–384. doi: 10.1002/hep.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koch A., Horn A., Duckers H., Yagmur E., Sanson E., Bruensing J. Increased liver stiffness denotes hepatic dysfunction and mortality risk in critically ill non-cirrhotic patients at a medical ICU. Crit Care. 2011;15:R266. doi: 10.1186/cc10543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Millonig G., Reimann F.M., Friedrich S., Fonouni H., Mehrabi A., Buchler M.W. Extrahepatic cholestasis increases liver stiffness (FibroScan) irrespective of fibrosis. Hepatology. 2008;48:1718–1723. doi: 10.1002/hep.22577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foucher J., Chanteloup E., Vergniol J., Castacra L., Bail B.L., Adhoute X. Diagnosis of cirrhosis by transient elastography (FibroScan): a prospective study. Gut. 2006;55:403–408. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuzaki R., Tateishi R., Yoshida H., Goto E., Sato T., Ohki T. Prospective risk assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with chronic hepatitis C by transient elastography. Hepatology. 2009;49:1954–1961. doi: 10.1002/hep.22870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Serag H.B. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. 1264-1273.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venook A.P., Papandreou C., Furuse J., Ladrón de Guevara L. The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective. Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl. 4):5–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Association for Study of Liver, Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado EASL-ALEH clinical practice guidelines: non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:237–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.European Association For The Study Of The Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Tsao G., Friedman S., Iredale J., Pinzani M. Now there are many (stages) where before there was one: in search of a pathophysiological classification of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1445–1449. doi: 10.1002/hep.23478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hytiroglou P., Snover D.C., Alves V., Balabaud C., Bhathal P.S., Bioulac-Sage P. Beyond “cirrhosis”: a proposal from the International liver pathology study group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:5–9. doi: 10.1309/AJCP2T2OHTAPBTMP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feier D., Lupsor Platon M., Stefanescu H., Badea R. Transient elastography for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in viral C liver cirrhosis. Is there something else than increased liver stiffness? Journal of gastrointestinal and liver diseases. JGLD. 2013;22:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]