Abstract

Introduction

The optimal treatment for biliary obstruction in pancreatic cancer remains controversial between surgical bypass and endoscopic stenting.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of unresected pancreatic cancer patients in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Florida State Inpatient and Ambulatory Surgery databases (2007–2011). Propensity score matching by procedure. Primary outcome was reintervention, and secondary outcomes were readmission, overall length of stay (LOS), discharge home, death and cost. Multivariate analyses performed by logistic regression.

Results

In a matched cohort of 622, 20.3% (63) of endoscopic and 4.5% (14) of surgical patients underwent reintervention (p < 0.0001) and 56.0% (174) vs. 60.1% (187) were readmitted (p = 0.2909). Endoscopic patients had lower median LOS (10 vs. 19 days, p < 0.0001) and cost ($21,648 vs. $38,106, p < 0.0001) as well as increased discharge home (p = 0.0029). No difference in mortality on index admission. On multivariate analysis, initial procedure not predictive of readmission (p = 0.1406), but early surgical bypass associated with lower odds of reintervention (OR = 0.233, 95% CI 0.119, 0.434).

Discussion

Among propensity score-matched patients receiving bypass vs. stenting, readmission and mortality rates are similar. However, candidates for both techniques may experience fewer subsequent procedures if offered early biliary bypass with the caveats of decreased discharge home and increased cost/LOS.

Introduction

In the 80% of patients diagnosed with advanced, unresectable pancreatic cancer, biliary obstruction is common.1 Options for management include surgical biliary bypass or endoscopic stenting. Endoscopic stenting has several advantages: it can be performed on an outpatient basis, without general anesthesia or abdominal incisions, and is less invasive than surgery. However, stents can become occluded resulting in cholangitis or pancreatitis, they can migrate and erode through surrounding structures, and they may require exchange or replacement.2

The literature comparing early surgical bypass to endoscopic stenting is outdated and inconsistent, and the optimal technique for relief of obstructive jaundice remains controversial.

In this study, we compared post-procedural outcomes between unresected pancreatic cancer patients equally likely to undergo early surgical bypass and endoscopic biliary stenting, focusing on the need for reintervention. We hypothesized that while reintervention would be more common in the stent group, a higher rate of death, inpatient readmission and cost would be associated with biliary bypass.

Methods

Design

We performed a retrospective review of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Florida State Inpatient Database (SID) and State Ambulatory Surgery and Services Database (SASD). Both databases are all-payer administrative database assembled by the HCUP, part of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).3 The SID includes discharge data from inpatient discharges from acute care hospitals, and the SASD includes data from ambulatory encounters where an invasive procedure was performed. The databases include patient and facility characteristics for each encounter. Diagnosis and procedure data is available as ICD-9 procedure and diagnosis codes as well as CPT codes. A unique HCUP visitlink variable is assigned to each patient to allow individual patients to be followed across time and at multiple institutions.

Patients with pancreatic cancer and age 18 years or older during 2007–2011 were identified using query of ICD-9 diagnosis codes (157). Any inpatient or ambulatory endoscopic biliary stents or surgical biliary bypasses were identified using ICD-9 procedure codes and CPT codes. Procedure codes for endoscopic biliary included endoscopic insertion of or exchange of a stent in the pancreatic or bile ducts (ICD-9 codes: 51.87, 52.93; CPT codes: 43267, 43268, 43269, 43274, 43276, 47556, 47801). Procedure codes for surgical biliary bypass included choledochoenterostomy, cholecystenterostomy and anastomosis of the hepatic duct to the gastrointestinal tract (ICD-9 codes: 51.36, 51.37, 51.39; CPT codes: 47570, 47612, 47701, 47720, 47721, 47740, 47741, 47760, 47765, 47780, 47785). In order to identify those biliary bypass patients who had a concurrent gastrojejunostomy performed (a “double bypass”), ICD-9 code 44.39 and CPT codes 43820, 43825, and 48547 were used.

The Visitlink variable was used to examine all inpatient and ambulatory visits for each individual patient across time. Patients were divided into two groups based on the first biliary decompression procedure: endoscopic stent placement or early surgical biliary bypass. Those with a surgical bypass performed within 30 days of initial endoscopic stent placement were classified as early surgical bypass patients because the decision to proceed to surgery was likely to offer definitive management (replacing a temporary plastic stent, for example), rather than to address an early stent failure. Patients with an inpatient pancreatic resection at any time during the study period were identified by ICD-9 code (52.5, 52.6, 52.7) and excluded from analysis.

Propensity score matching

Patient demographic were collected from the discharge record—inpatient or ambulatory—associated with the index procedure. These included sex, age, median ZIP code income, insurance type, and race. Patients with missing characteristics for the index procedure were removed from the analysis. The extent of comorbid conditions was calculated using an Elixhauser score, generated using the HCUP Comorbidity Software, Version 3.7.4 This system was specifically designed for use in large administrative datasets and identifies comorbidities using ICD-9 codes and Diagnosis-Related Groups. The year and urgency of the index procedure was also identified.

Due to concerns that many patients in the initial stent population would not be candidates for surgical bypass, the decision was made a priori to create a propensity score matched cohort in order to analyze patients with similar likelihoods of undergoing endoscopic stent placement and surgical bypass. A logistic regression model was created to predict likelihood of undergoing surgical bypass. Covariates included in the model were year of index procedure, urgency of index procedure, sex, race (dichotomized into white and non-white), age (dichotomized into less than 65 and 65 or greater), Elixhauser comorbidity score (dichotomized into 0–1 and 2 or greater), median ZIP income (dichotomized into upper and lower halves), and primary payer (grouped into Medicare, Medicaid, private, and other or none). We matched using a 1:1, optimal, nearest neighbor matching with calipers and without replacement. Calipers were set at 0.2 of the standard deviation of the distribution of the propensity score. This matching strategy and caliper range will eliminate 99% of the bias among the measured confounders.5

Patient outcomes

The primary outcome was subsequent intervention for management of biliary obstruction at any point after the initial intervention. This was broken down into endoscopic stent replacement or exchange, surgical biliary bypass, or percutaneous procedures facilitating biliary drainage (ICD-9 codes: 51.01, 51.96, 51.98, 51.99; CPT codes: 47490, 47510, 47511, 47552, 47553, 47554, 47555, 47556, 47630). Secondary outcomes include inpatient readmission at least once after the initial procedure, length of stay (LOS) at the time of the index procedure, discharge to home at the time of the index procedure, death during index admission, total LOS during the study period and total cost of care during the study period. A sensitivity analysis for LOS was performed among patients receiving a biliary bypass with a concurrent gastrojejunostomy. The first revisit (whether inpatient or ambulatory) was queried to identify patients with obstructive complications—cholangitis (ICD-9 code: 576.1), evidence of biliary obstruction (ICD-9 code: 576.2, 782.4), or acute pancreatitis (ICD-9 code: 577.0).

Cost of care was determined using charge data for each inpatient and ambulatory encounter. Charge information available does not reflect the true cost of services or the reimbursement. To approximate costs by converting billed charge we used the supplemental SID HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratio files.6 Based on all-payer inpatient costs for each hospital as reported to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), these files contain hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratios.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics, dichotomized or categorized to enhance clinical relevance, were compared between the initial endoscopic stent and the early surgical bypass groups using chi-square. These analyses were performed on the unmatched and propensity score matched cohorts.

For patient outcomes, chi-square test was used to evaluate binary outcome variables for the propensity matched cohort. Continuous outcome variables—LOS, cost, and number of readmissions—were assumed to be non-normal. Median values and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated for the early surgical bypass and initial endoscopic stent groups. Comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Univariate logistic regression modeling of likelihood of subsequent procedure and inpatient readmission were performed for the propensity score matched cohort. Multivariate logistic regression models predicting subsequent procedure and readmission were created using all available patient characteristics as well as the procedure group—initial endoscopic stent or early surgical bypass—and index procedure characteristics, including length of stay, urgency, and year of procedure. For all regression modeling, Firth's penalized maximum likelihood for rare events was utilized.7

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical analysis software, version 9.3/9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). For all analyses, p value of less 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cell sizes less than 11 are not reported in compliance with the HCUP data use agreement. This study was approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board. No authors have conflicts of interest.

Results

Characteristics

1803 and 312 patients underwent endoscopic treatment vs. early surgical bypass, respectively. 197 (63.1%) of patients who received a biliary bypass also received a gastrojejunostomy (a “double bypass”). 154/158 (97.5%) of participating hospitals performed at least one stent, while 71/158 (44.9%) performed at least one bypass and one stent in the inpatient setting over the study period. In the unmatched cohort, patients who received an endoscopic stent were older (p < 0.0001) and had different insurance coverage (p = 0.0002). Stents were more likely to be performed after 2007 (p = 0.0001) and on an emergent basis (p < 0.0001). Patient characteristics before propensity score matching are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by initial procedure for all patients

| Stent |

Bypass |

p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Characteristics | 1803 | 85.2% | 312 | 14.8% | |

| Age ≥65 | 1363 | 75.6% | 198 | 63.5% | <0.0001 |

| Female | 918 | 50.9% | 153 | 49.0% | 0.5404 |

| White race | 1399 | 77.6% | 243 | 77.9% | 0.9091 |

| Lower ZIP median income | 1066 | 59.1% | 191 | 61.2% | 0.4867 |

| Elixhauser 0 or 1 | 330 | 18.3% | 50 | 16.0% | 0.3334 |

| Insurance | 0.0002 | ||||

| Medicare | 1315 | 72.9% | 193 | 61.9% | |

| Medicaid | 100 | 5.6% | 28 | 9.0% | |

| Private | 294 | 16.3% | 76 | 24.4% | |

| Other | 94 | 5.2% | 15 | 4.8% | |

| Year | 0.0001 | ||||

| 2007 | 322 | 17.9% | 89 | 28.5% | |

| 2008 | 367 | 20.4% | 64 | 20.5% | |

| 2009 | 372 | 20.6% | 52 | 16.7% | |

| 2010 | 374 | 20.7% | 63 | 20.2% | |

| 2011 | 368 | 20.4% | 44 | 14.1% | |

| Emergent admission | 1459 | 80.9% | 128 | 41.0% | <0.0001 |

After propensity score matching, 622 patients were analyzed, and there were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics by initial procedure for propensity score matched patients

| Stent |

Bypass |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Characteristics | 311 | 50.0% | 311 | 50.0% | |

| Age ≥65 | 211 | 67.9% | 198 | 63.7% | 0.2720 |

| Female | 156 | 50.2% | 153 | 49.2% | 0.8099 |

| White race | 249 | 80.1% | 242 | 77.8% | 0.4912 |

| Lower ZIP median income | 186 | 59.8% | 191 | 61.4% | 0.6816 |

| Elixhauser 0 or 1 | 50 | 16.1% | 50 | 16.1% | 0.9999 |

| Insurance | 0.7290 | ||||

| Medicare | 205 | 65.9% | 193 | 62.1% | |

| Medicaid | 25 | 8.0% | 27 | 8.7% | |

| Private | 70 | 22.5% | 76 | 24.4% | |

| Other | 11 | 3.5% | 15 | 4.8% | |

| Year | 0.4293 | ||||

| 2007 | 81 | 26.0% | 89 | 28.6% | |

| 2008 | 78 | 25.1% | 64 | 20.6% | |

| 2009 | 56 | 18.0% | 52 | 16.7% | |

| 2010 | 64 | 20.6% | 62 | 19.9% | |

| 2011 | 32 | 10.3% | 44 | 14.2% | |

| Emergent admission | 125 | 40.2% | 128 | 41.2% | 0.8066 |

PS, propensity score.

Outcomes before matching

Bypassed patients were more likely to have an index length of stay longer than 10 days (62.2% [194] vs. 24.6% [444], p < 0.0001) and were less likely to be discharged home (48.1% [150] vs. 56.1% [1012], p = 0.0083). They were less likely to have an obstructive complication or undergo a subsequent procedure (both p < 0.0001). Unadjusted inpatient readmission rates were similar (54.5% [983] stenting vs. 60.0% [187] bypass, p = 0.0756). Endoscopically stented patients had a mortality rate during index procedure admission of 2.2% (39) vs. 4.8% (15) in the surgical bypass group (p = 0.0062). Overall length of stay and cost of care were lower after endoscopic stenting (both p < 0.0001).

Outcomes after matching

After matching, patients with early surgical bypass had longer LOS (p < 0.0001) and were less likely to be discharged to home postoperatively (p = 0.0029). 63.7% (198) of initial endoscopic stent and 68.2% (212) of early surgical patients had at least one subsequent revisit, whether inpatient or outpatient (p = 0.2363), while 56.0% (174) and 60.1% (187) were readmitted at least once to an inpatient facility, respectively (p = 0.2909). Endoscopic stent patients had higher rates of reinterventions (p < 0.0001) as well as higher rates of obstructive complications during revisits (p < 0.0001). However, there was no statistically significant difference between mortality rates. Endoscopic patients had a lower index length of stay (p < 0.0001), lower median total length of stay (p < 0.0001), and total costs of care (p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes by initial procedure for propensity score matched patients

| Stent | Bypass | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Procedure admission |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

| LOS ≥10 days | 62 (19.9%) | 193 (62.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Discharged to home | 186 (59.8%) | 149 (47.9%) | 0.0029 |

| Mortality |

<11 |

15 (4.8%) |

NS |

|

Post-procedure |

n (%) |

n (%) |

|

| Any inpatient readmission | 174 (56.0%) | 187 (60.1%) | 0.2909 |

| Subsequent procedure | 63 (20.3%) | 14 (4.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Obstructive complicationa |

71 (22.8%) |

14 (4.5%) |

<0.0001 |

|

All care |

(median [IQR]) |

(median [IQR]) |

|

| Cost (USD) | $21 648 [$12 408,$37 530] | $38 106 [$25 678,$53 960] | <0.0001 |

| LOS (days) | 10 [6,20] | 19 [12,28] | <0.0001 |

LOS, length of stay; NS, not significant. “All Care” includes LOS and cost of index admission plus all subsequent admissions.

Cholangitis, evidence of biliary obstruction, or acute pancreatitis on first revisit.

Bypass patients who concurrently received a gastrojejunostomy had an index median LOS of 12 (IQR 8, 19) compared to 11 (IQR 8, 17) for patients receiving solely a biliary bypass.

On univariate analysis, initial procedure type was not a statistically significant predictor of inpatient readmission (OR 1.187; 95% CI 0.863–1.632). However, early surgical bypass was associated with lower odds of subsequent intervention (OR 0.191; 95% CI 0.102–0.336).

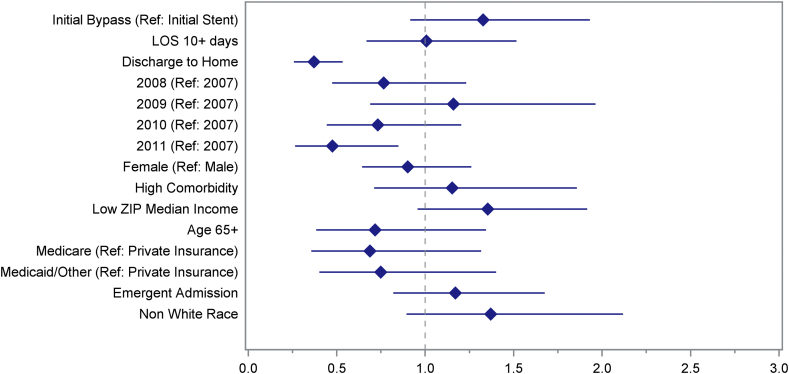

Multivariate analysis

In propensity score matched patients, the only protective characteristics were discharge to home following the initial procedure (OR 0.371; 95% CI 0.257–0.533) and year of procedure 2011 vs. 2007 (OR 0.475; 95% CI 0.264–0.848). Initial procedure type was not a significant predictor of inpatient readmission (OR 1.327; 95% CI 0.915–1.930). LOS, gender, comorbidities, income, age, insurance status, urgency of initial procedure, and race were also not significant (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Multivariate analysis of odds of inpatient readmission in propensity score matched patients. Adjusted odds ratios with their 95% confidence intervals presented

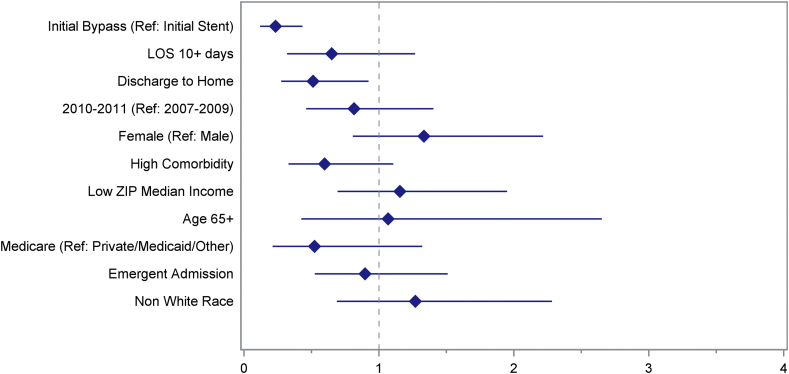

Both early surgical bypass (OR 0.233; 95% CI 0.119–0.434) and discharge to home after the initial procedure (OR 0.512; 95% CI 0.275–0.922) were protective of reintervention. Conversely, LOS, year, gender, comorbidities, income, age, insurance status, and urgency of initial procedure were not predictive of reintervention (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Multivariate analysis of odds of reintervention in propensity score matched patients. Adjusted odds ratios with their 95% confidence intervals presented

Discussion

Endoscopic stenting is more commonly performed than surgical bypass for relief of biliary obstruction in unresectable pancreatic cancer patients. Among propensity score-matched patients, readmission rates are similar, but patients undergoing endoscopic stents require more subsequent interventions, including further stenting. Mortality rates during index admission are similar. However, endobiliary stenting is associated with decreases in overall length of stay and cost, as well as a greater likelihood of being discharged home.

Previous findings are mixed regarding the preferred strategy to maximize quality of life. Early randomized control trials (RCTs) found no differences in complication rates or survival in patients receiving endoscopic stenting and those receiving surgical bypass.8 Only one showed significantly increased recurrence of biliary obstruction after stenting.9 When early RCT data is combined, plastic stents are associated with fewer complications than surgery but higher risk of recurrent biliary obstruction.10 Some early retrospective studies confirmed a higher incidence of recurrent jaundice for stented patients and improved long-term quality of life after surgical bypass.11, 12 Others reported higher rates of procedure-related morbidity for the surgical approach.13 However, these studies were small and performed early in the era of endoscopy and stenting, before advancements in expandable metal stents, for example.14 Furthermore, advances in palliative treatments may help patients with terminal pancreatic cancer live longer.15 Moreover, with recent advances in chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer, improved survival times might provide more time for potential complications, reinterventions, and rehospitalizations to occur.16, 17 More recent data is single-center and highly variable. The latest RCT (using metal stents) found no differences in readmission or complication rates, but did find reduced cost and improved quality of life for patients receiving endoscopic stenting.18 While some non-randomized studies concur, others report higher rates of complications, subsequent procedures, and readmissions after stenting.19, 20, 21, 22

This multi-institutional study is the largest contemporary investigation examining readmissions and reinterventions for patients receiving surgical bypass vs. endoscopic stenting. Our results are overall aligned with a comprehensive meta-analysis of five RCTs of palliative management in malignant biliary obstruction due to pancreatic or peri-pancreatic cancer.23 As we did, the meta-analysis found a lower rate of recurrent biliary obstruction (requiring reintervention) in the surgery group. From a literature review of non-randomized trials, the authors of the meta-analysis estimated that the endoscopic group spent more days in the hospital before death. In contrast, we show that readmission rates between techniques are equivalent both before and after matching, overall median time in hospital is lower for endoscopy, and total cost associated with endoscopic stenting is lower. Finally, we confirm a mortality rate for surgical bypass that is not insubstantial but show that mortality rates for bypass and stenting are statistically equivalent in matched patients equally likely to receive either.24

Our study has several limitations. This is a non-randomized study, and propensity score adjustment does not account for unmeasured confounders. Despite the use of both inpatient and outpatient data from a large state over 5 years, the surgical biliary bypass is small, leading to a small matched cohort. The majority of patients in the biliary bypass group also received a gastrojejunostomy, although sensitivity analysis showed that this did not meaningfully affect length of stay. Finally, the use of an administrative data set limits the availability of clinical information captured in diagnosis codes. There is no data on stage of presentation, tumor size or duodenal involvement, functional status, or quality of life. We also do not discuss other treatment interventions outside of bypass and stenting, and it is unknown what type of stent (plastic vs. metal) was used in the stenting group. This study concludes in 2011 and may not account for the rising use of metal stents since that period. Most importantly, there is no data on overall survival but only death during hospitalization, so variable follow-up time cannot be accounted for in this analysis.

Although not perfect proxies for burden of complications and quality of life, the chosen outcomes of readmission and reinterventions are reasonable quantitative measures of utilization of the healthcare system. Furthermore, by accounting for both inpatient and outpatient visits, we provide the most complete picture of the subsequent course of unresected pancreatic cancer patients who are stented vs. surgically bypassed. Although we cannot differentiate what type of stent was placed, we accounted for likely plastic stent placement by including surgical bypasses occurring within 30 days after a stent placement in the early surgical bypass group.

Endoscopic stenting has numerically overtaken surgical bypass as the technique of choice for management of biliary obstruction: in our overall cohort, 85% (1803) of patients received endoscopic stenting and only 15% (312) surgical bypass. Stenting was widely available—all inpatient facilities except for four performed at least one endoscopic stent. Biliary bypass was commonly performed with concurrent gastrojejunostomy. In a matched cohort of 311 patients, about 60% of patients undergoing bypass vs. stenting had at least one inpatient readmission, with no statistically significant difference between the groups. However, higher rates of reintervention are seen in the endoscopic treatment group. Nonetheless, endoscopic stenting is associated with increased likelihood of discharge home, decreased overall hospital length of stay and total cost.

The decision about whether to proceed with a biliary stent or surgical bypass in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer depends on several factors including life expectancy, safety, and patient preference. Our results present a trade-off between fewer reinterventions in the bypass group, but increased overall cost/hospital length of stay and lower rates of discharge home, with equivalent rates of reinterventions and mortality. We offer a contemporary confirmation of the following paradigm for decisions regarding surgical bypass vs. stenting: Patients with impaired performance status or advanced disease stage may be better served with “definitive” endobiliary stenting, which minimizes up-front inpatient length of stay and cost of care.25 However, these patients should have rapid access to advanced endoscopy as needed for complications. Conversely, carefully selected patients with low surgical risk, good performance status, and non-metastatic disease who are projected to have reasonable survival should be considered for surgical bypass. As advances in pancreatic cancer care and techniques for relief of biliary obstruction occur, including targeted therapy, advanced endoscopy, and minimally invasive hepatopancreaticobiliary surgery, the algorithm will need to be reevaluated and recalibrated.

The majority of patients with obstructive jaundice from pancreatic cancer undergo endoscopic stenting. In patients eligible for surgery, surgical bypass may offer a more durable solution than biliary stenting for biliary obstruction. However, it involves a decreased likelihood of post-procedural discharge home and increased overall length of stay and cost. The adjusted risks of readmission and mortality between bypass and stent are equal. Patients that are reasonable candidates for either technique may experience fewer subsequent invasive procedures if offered early surgical biliary bypass, at the expense of increased overall cost and days in hospital.

Funding sources

Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Award, American Surgical Association Foundation Fellowship, American Cancer Society MSRG 10-003-01 (to JFT).

Pyrtek Fund Research Fellowship (to LAB).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Bliss and Tseng had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology annual meetings.

References

- 1.Kruse E.J. Palliation in pancreatic cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costamagna G., Pandolfi M. Endoscopic stenting for biliary and pancreatic malignancies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:59–67. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(HCUP) HCaUP . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: June 2014. HCUP databases.www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp [April 16, 2015]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elixhauser A., Steiner C., Harris D.R., Coffey R.M. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin P.C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(HCUP) HCaUP . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP); 2014. Cost-to-charge ratio files.www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp [updated December 2014; cited 2015 April 16, 2015]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinze G., Schemper M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med. 2002;21:2409–2419. doi: 10.1002/sim.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen J.R., Sorensen S.M., Kruse A., Rokkjaer M., Matzen P. Randomised trial of endoscopic endoprosthesis versus operative bypass in malignant obstructive jaundice. Gut. 1989;30:1132–1135. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.8.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith A.C., Dowsett J.F., Russell R.C., Hatfield A.R., Cotton P.B. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet. 1994;344:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss A.C., Morris E., Leyden J., MacMathuna P. Malignant distal biliary obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic and surgical bypass results. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyoty M.K., Nordback I.H. Biliary stent or surgical bypass in unresectable pancreatic cancer with obstructive jaundice. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuzzo G., Clemente G., Cadeddu F., Giovannini I. Palliation of unresectable periampullary neoplasms. “surgical” versus “non-surgical” approach. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1282–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santagati A., Ceci V., Donatelli G., Pasqualini M.J., Silvestri F., Pitasi F. Palliative treatment for malignant jaundice: endoscopic vs surgical approach. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2003;7:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huggett M.T., Ghaneh P., Pereira S.P. Drainage and bypass procedures for palliation of malignant diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2010;22:755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaccaro V., Sperduti I., Vari S., Bria E., Melisi D., Garufi C. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: is there a light at the end of the tunnel? World J Gastroenterol – WJG. 2015;21:4788–4801. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein D., El-Maraghi R.H., Hammel P., Heinemann V., Kunzmann V., Sastre J. nab-Paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer: long-term survival from a phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore M.J., Goldstein D., Hamm J., Figer A., Hecht J.R., Gallinger S. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artifon E.L., Sakai P., Cunha J.E., Dupont A., Filho F.M., Hondo F.Y. Surgery or endoscopy for palliation of biliary obstruction due to metastatic pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2031–2037. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott E.N., Garcea G., Doucas H., Steward W.P., Dennison A.R., Berry D.P. Surgical bypass vs. endoscopic stenting for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. HPB. 2009;11:118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikfarjam M., Hadj A.K., Muralidharan V., Tebbutt N., Fink M.A., Jones R.M. Biliary stenting versus surgical bypass for palliation of periampullary malignancy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:82–89. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunpaweravong S., Ovartlarnporn B., Khow-ean U., Soontrapornchai P., Charoonratana V. Endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in advanced malignant distal bile duct obstruction: cost-effectiveness analysis. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:262–265. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueda J., Kayashima T., Mori Y., Ohtsuka T., Takahata S., Nakamura M. Hepaticocholecystojejunostomy as effective palliative biliary bypass for unresectable pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glazer E.S., Hornbrook M.C., Krouse R.S. A meta-analysis of randomized trials: immediate stent placement vs. surgical bypass in the palliative management of malignant biliary obstruction. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;47:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartlett E.K., Wachtel H., Fraker D.L., Vollmer C.M., Drebin J.A., Kelz R.R. Surgical palliation for pancreatic malignancy: practice patterns and predictors of morbidity and mortality. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1292–1298. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maosheng D., Ohtsuka T., Ohuchida J., Inoue K., Yokohata K., Yamaguchi K. Surgical bypass versus metallic stent for unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:367–373. doi: 10.1007/s005340170010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]