Abstract

Clinical trials shows that remote ischemic preconditioning (IPC) can protect against contrast induced nephropathy (CIN) in risky patients, however, the exact mechanism is unclear. In this study, we explored whether renalase, an amine oxidase that has been previously shown to mediate reno-protection by local IPC, would also mediate the same effect elicited by remote IPC in animal model. Limb IPC was performed for 24 h followed by induction of CIN. Our results indicated that limb IPC prevented renal function decline, attenuated tubular damage and reduced oxidative stress and inflammation in the kidney. All those beneficial effects were abolished by silencing of renalase with siRNA. This suggests that similar to local IPC, renalase is also critically involved in limb IPC-elicited reno-protection. Mechanistic studies showed that limb IPC increased TNFα levels in the muscle and blood, and up-regulated renalase and phosphorylated IκBα expression in the kidney. Pretreatment with TNFα antagonist or NF-κB inhibitor, largely blocked renalase expression. Besides, TNFα preconditioning increased expression of renal renalase in vivo and in vitro, and attenuated H2O2 induced apoptosis in renal tubular cells. Collectively, our results suggest that limb IPC-induced reno-protection in CIN is dependent on increased renalase expression via activation of the TNFα/NF-κB pathway.

Keywords: Limb ischemic preconditioning, Contrast induced nephropathy, Renalase, TNFα

Highlights

-

•

Limb ischemic preconditioning (IPC) leads to renalase upregulation in kidney tissue.

-

•

Renalase is critically involved in limb IPC-elicited renal protection in contrast induced nephropathy.

-

•

Limb IPC induces renalase upregulation via activation of the tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)/ nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway.

Renalase, a kidney-secreted protein, serves as extracellular pro-survival signals and has been reported to participate in the local ischemic preconditioning (IPC) induced renal protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Whether renalase contributes to the beneficial effects of limb IPC on contrast induced nephropathy (CIN) remains unknown. This study revealed that limb IPC induced reno-protection in CIN was at least in part dependent on increased renalase expression, which is evidenced by our observations that knockdown of renalase abolished reno-protective effects conferred by limb IPC. The upregulation of renalase elicited by limb IPC may be mediated by activation of TNFα/NF-κB pathway.

1. Introduction

Contrast induced nephropathy (CIN) has become one of the leading causes of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury (AKI) (Nash et al., 2002) as contrast agents are widely utilized in clinical diagnostic and interventional procedures (Asif and Epstein, 2004, Wang et al., 2013). CIN following cardiac angiogram or intervention is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 20% in unselected patients and a 1-year mortality rate of up to 66% (Rihal et al., 2002, Shlipak et al., 2002, Best et al., 2002). However, there is still no effective prophylactic regimen available to prevent occurrence of CIN (Gassanov et al., 2014). Therefore, it is urgent to develop novel strategies to decrease CIN incidence and to improve clinical outcomes.

Accumulated evidence indicates that CIN is the result of combined direct toxic effects of contrast media and hypoxic renal injury (Sendeski, 2011). Renal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury due to contrast induced hemodynamic alteration of renal blood flow plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of CIN (Evans et al., 2013, Persson et al., 2005). Besides, contrast media induced production of free oxygen radicals also contributes to renal tubular cell injury (Pisani et al., 2013). Thus, the strategies for protecting against hypoxic injury may also be effective for prevention and treatment of CIN.

Remote ischemic preconditioning (IPC) is defined as temporal episodes of ischemia of remote organ before a subsequent prolonged I/R injury. It can facilitate other organs to tolerate a more severe injury and to reduce the extent of distant organ damage. The tissue protective effects of this approach have been reported in myocardial infarction and AKI (Przyklenk and Whittaker, 2011, Wever et al., 2011). Limb IPC, one of remote IPC represents a promising approach for clinical intervention, has been tested in the prevention of CIN in clinic trials and gained encouraging results, especially in patients with a high risk of CIN (Er et al., 2012, Menting et al., 2015). However, its reno-protective mechanism remains elusive.

Previous studies have shown that remote IPC is involved in activation of multifactorial anti-inflammatory, neuronal, and humoral signaling pathways (Gassanov et al., 2014). For example, remote IPC could confer cardio-protection against ischemia through up-regulating erythropoietin (EPO) and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF1α) in the kidney (Oba et al., 2015). EPO preconditioning is also able to protect against cardiac and kidney I/R injury (Gardner et al., 2014). As such, some factors/molecules produced in the kidney may play a role in the defense mechanism of remote IPC. Thus, it will be interesting to identify novel kidney-secreted proteins contributing to renal protection under remote IPC.

Among numerous candidates that exert a reno-protective effects, renalase is not only a kidney-originated amine oxidase, but also a molecule that is subjected to HIF-1 regulation at transcriptional level (Wang et al., 2015c, Du et al., 2015). It has been documented that renalase can regulate blood pressure and protect against both heart and kidney I/R injury (Lee et al., 2013, Wang et al., 2014a, Wang et al., 2014b, Wang et al., 2015a, Wang et al., 2015c, Du et al., 2015, Guo et al., 2014). Our previous study also demonstrated that exogenous administration of renalase was effective in alleviating CIN in rats (Zhao et al., 2015) and that local IPC induced cortex renalase upregulation via HIF-1α dependent mechanism. Furthermore, renalase plays a vital role in reno-protection of local IPC against I/R induced AKI (Wang et al., 2015c). In line with our observations, other studies showed that renalase expression was elevated and attenuated cardiac injury in mice challenged with cardiac I/R (Du et al., 2015). Recently, it has been reported that renalase may function as a pro-survival/growth factor and signals via the receptor plasma membrane calcium ATPase subtype 4b (PMCA4b) (Wang et al., 2015d, Guo et al., 2016). Nevertheless, there is no study to address the role of renalase in remote IPC against kidney I/R injury so far.

In the present study, we examined whether renal renalase would be up-regulated in rats subjected to limb IPC and whether such a remote IPC-induced increase of renalase expression would contribute to reno-protective effects in CIN. In addition, we also investigated the potential mechanisms by which limb IPC regulated renalase expression in the kidney.

2. Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital.

2.1. Reagents, animals and cells

Ioversol was purchased from Hengrui Corp. (Jiangsu, China). N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), indomethacin, tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK, a nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, NF-κB inhibitor), pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC, an NF-κB inhibitor), 3-(5′-Hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl)-1-benzyl indazole (YC-1, a HIF-1α inhibitor), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Humira, a TNFα antagonist, was provided by AbbVie (North Chicago, IN, USA). The cholesterol-conjugated specific renalase siRNA were provided by Shanghai Biotend Corp. (Shanghai, China). Male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 200 ± 20 g, were provided by Shanghai Science Academy animal center (Shanghai, China). All the rats were housed under controlled conditions of light (12 h dark/12 h light cycle) and temperature (20–23 °C), and fed with standard diet and tap water. HK2 cells from ATCC (Rockefeller, MD, USA) were used as a proximal renal tubular epithelial cell model.

2.2. Rat models of delayed remote IPC and CIN

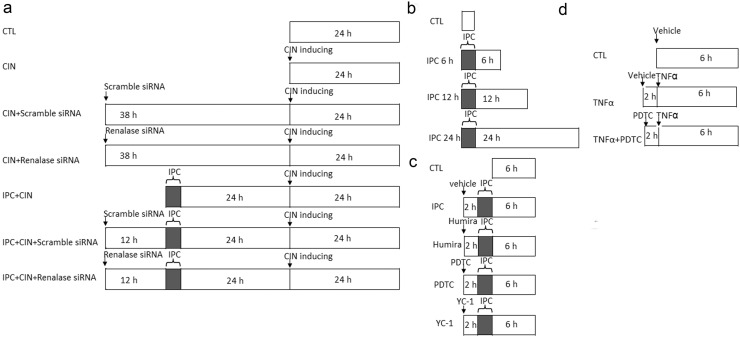

All the animal experiment protocols were demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The schema for animal study protocols. a. Limb ischemic preconditioning followed (IPC) by contrast-induced renal injury inducing and renalase blocking protocol. b. Renalase expression after limb IPC. c. Limb IPC induced renalase expression with TNFα blocking or NF-κB or HIF-1 blocking. d. TNFα preconditioning with NF-κB blocking. The rats were randomly divided into desired groups (as showed in the schema) with 6 animals in each group.

Study 1: Limb IPC protects against CIN via renalase (Fig. 1A).

The rats were divided into a sham-operated group (Sham), a remote IPC group (IPC), a CIN group, an IPC + CIN group, a CIN + Scramble siRNA group, a CIN + Renalase siRNA group, an IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA group and an IPC + CIN + Renalase siRNA group, N = 6 in each group. Remote IPC was delivered by occluding hind limb blood flow with a tightened tourniquet around the upper thigh for 6 cycles of 10-min occlusion followed by 10-min release under anesthesia with 50 mg/kg pentobarbital. The limb ischemia was confirmed by pallor and cyanosis of the lower limb below the tourniquet. CIN was induced similarly to that described previously (Zhao et al., 2015). Briefly, rats were given a tail vein injection of indomethacin (10 mg/kg), followed by Ioversol (3 g/kg organically bound iodine) and l-NAME.

In the IPC + CIN group, CIN were induced at 24 h after limb IPC. In rats of the CIN + Scramble siRNA group, CIN + Renalase siRNA group, IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA group and IPC + CIN + Renalase siRNA group, a midline laparotomy was performed after anesthetizing with 50 mg/kg pentobarbital. Then, scramble siRNA or renalase siRNA was injected into the bilateral renal cortex at 12 h before IPC or 38 h before CIN induction. Rats in the CIN or IPC + CIN groups were treated with the vehicle of the same volume at the same time points.

Study 2: limb IPC induces renalase expression (Fig. 1B).

Limb IPC was induced in rats first, followed by blood and tissues harvested at 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h (N = 6 in each group).

Study 3: limb IPC induces renalase expression via NF-κB (Fig. 1C).

Rats were divided into Sham group, IPC group, IPC + Humira group, IPC + PDTC group and IPC + YC-1 group (N = 6 in each group). Limb IPC was induced in IPC groups similarly to Study 1. Rats in IPC + Humira group, IPC + PDTC group, and IPC + YC-1 group were given an intraperitoneal injection of Humira (1 mg/kg), PDTC (100 mg/kg) or YC-1 (2 mg/kg) 2 h before IPC, respectively.

Study 4: TNFα induces renalase expression via NF-κB (Fig. 1C).

Rats were divided into Sham group, TNFα group, and TNFα + PDTC group (N = 6 in each group). Rats in IPC group received limb IPC induction. Rats in the TNFα group were given an intravenous injection of TNFα (0.1 μg/kg) or an intraperitoneal injection of PDTC 2 h before TNFα administration (Lecour et al., 2005). The tissues were harvested at 6 h after remote IPC.

2.3. Experiments in vitro

HK2 cells were cultured in K-SFM at 37 °C 5% CO2, supplemented with 5 ng/ml human recombinant EGF and 0.05 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract. HK2 cells were treated with TNFα to investigate renalase expression. TPCK was used as an NF-κB inhibitor in vitro. Besides, to determine whether TNFα preconditioning could protect against oxidative injury, HK-2 cells were pretreated with vehicle or TNFα (20 ng/ml) for 6 h and then were exposed to H202 (300 μmol/l) for an additional 12 h.

2.4. Assessment of renal function and oxidative injury

An automatic biochemical analyzer (7600, Hitachi, Japan) was employed to measure serum creatinine (Scr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) to assess the changes in renal function. Renal levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were measured using commercial kits following the manufacturer's protocol (Nanjing Jiancheng, Nanjing, China).

2.5. Histological injury assessment

The fixed left kidney was embedded in paraffin and then was cut into 3-μm sections. Histological alterations were evaluated by Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining. The renal injury was scored using grading tubular necrosis, loss of brush border, cast formation, and tubular dilatation in 10 randomly chosen, non-overlapping fields. The renal injury degree was estimated by the following criteria: 0, none; 1, 0–10%; 2, 11–25%; 3, 26–45%; 4, 46–75%; and 5, 76–100%, as described previously (Melnikov et al., 2002).

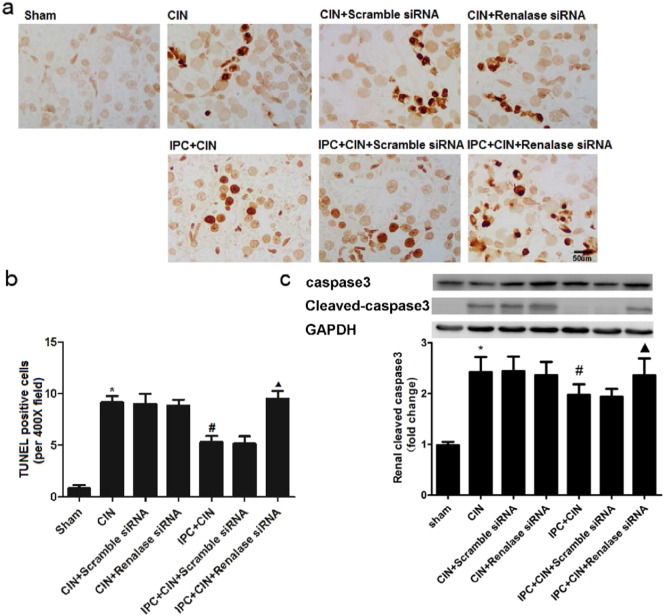

TUNEL staining was performed using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Numbers of TUNEL-positive tubular cells were quantified by counting 10 randomly chosen, non-overlapping fields per slide.

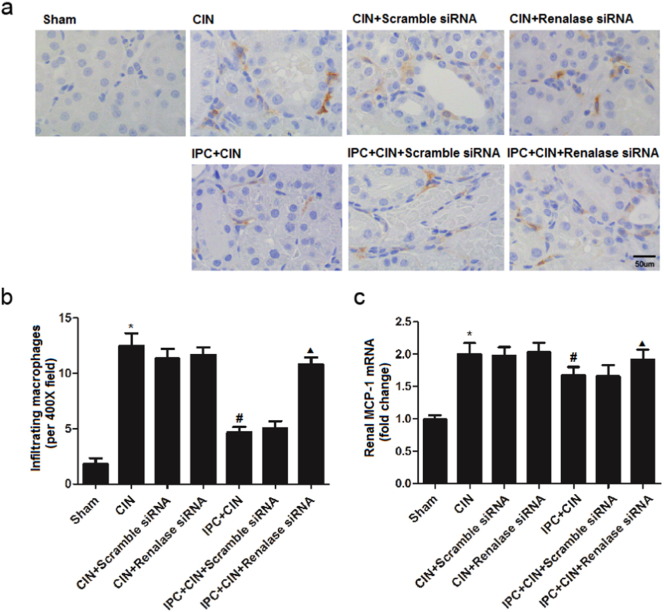

2.6. Macrophage infiltration in renal tissues

Immunohistochemistry was performed with an anti-CD68 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) to identify infiltrated macrophages in renal tissue as described previously (Wang et al., 2015b).

2.7. Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from HK2 cells or kidney tissues was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). mRNA levels were quantified using one-step real-time PCR with Taqman chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as described previously (Wang et al., 2014a). 18S rRNAs were used as internal normalizer for mRNAs. The primers for rat MCP-1 were 5′ATGCAGGTCTCTGTCACG3′ (forward) and 5′-CTAGTTCTCTGTCATACT-3′ (reverse); the primers of rat renalase and human renalase were 5′-AAAGAGGGAGATGGGTTAGTAGTGG-3′ (forward), 5′-TCGGTTCTGAGGAGGATGGAG-3′ (reverse), and 5′-GAAAAATCATTGCAGCCTCTCA-3′ (forward), 5′-AAGTTCTGCCTGTGCCTGTGTA-3′ (reverse), respectively.

2.8. Western blot analysis

Renalase and NF-κB levels were analyzed using western blot similar to that described previously (Wang et al., 2014a). The primary antibodies, anti-renalase, anti-caspase3, anti-Phospho-IκBα (Ser32) and anti-GAPDH were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA) (rabbit anti-renalase monoclonal antibody, 1:500 dilution), Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) (rabbit anti-Phospho-IκBα (Ser32) monoclonal antibody, 1:500 dilution; rabbit anti-caspase3 polyclonal antibodies, 1:1000 dilution) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) (goat anti-GAPDH polyclonal antibody, 1:5000 dilution), respectively. The secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz (horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The statistical software SPSS (Ver. 18.0) (USA) was used for data analysis. All the data were expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM). One-way ANOVA with Sidak compensation was employed for parametric data and Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’ compensation for non-parametric data comparison. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Limb IPC protects against CIN

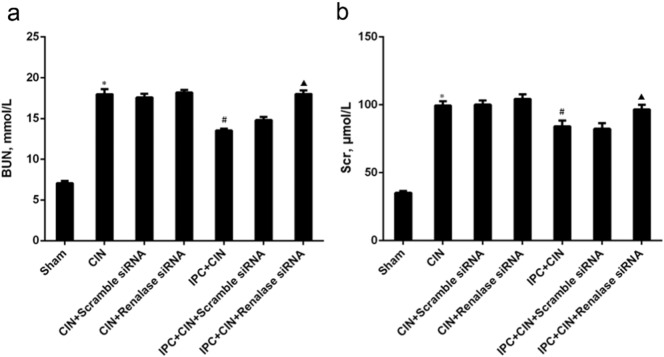

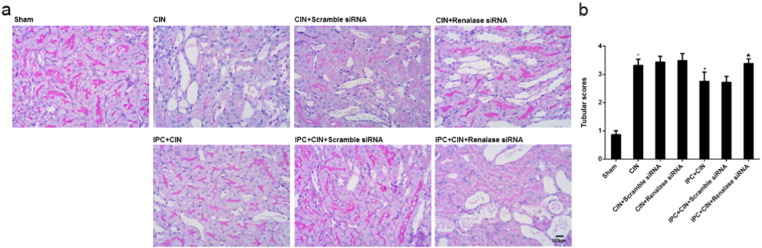

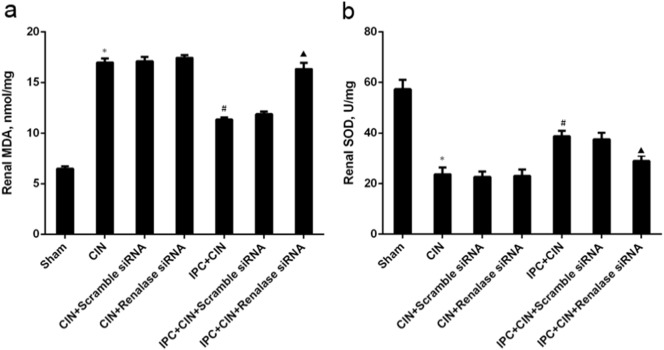

As shown in Fig. 2, the rats exhibited significant exacerbation of renal function 24 h in CIN groups after administration of contrast agent, as indicated by remarkable increase of Scr and BUN. Limb IPC significantly attenuated the renal impairment (Scr, limb IPC + CIN vs. CIN, P < 0.05; BUN, limb IPC + CIN vs. CIN, P < 0.05). Histological analysis further demonstrated that the renal tubular detachment, foamy degeneration, and necrosis of tubular cells were less severe in limb IPC + CIN group compared with CIN group (Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, limb IPC reduced the pathological tubular injury score in CIN (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, limb IPC decreased renal MDA levels and increased SOD levels after Ioversol injection (limb IPC + CIN vs. CIN, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4). Finally, limb IPC also significantly reduced tubular cell apoptosis and CD68-positive macrophage infiltration to the injured kidney (limb IPC + CIN vs. CIN, P < 0.05) as shown in Fig. 5, Fig. 6. These data indicated that limb IPC was able to protect against Ioversol-induced kidney injury via mitigating apoptosis, reducing inflammation and attenuating oxidative stress.

Fig. 2.

Knocking down renalase exacerbates contrast induced renal injury following limb ischemic preconditioning. Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) was induced in rats 24 h after limb ischemic preconditioning and at 24 h after CIN, blood and tissues were collected for further analysis. a. Blood urea nitrogen. b. Serum creatinine. Sham, sham-operated control group; CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group without Iimb IPC; CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with scramble siRNA injection; CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with renalase siRNA injection; IPC + CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC; IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with scramble siRNA injection; IPC + CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with renalase siRNA injection. N = 6, ⁎P < 0.01 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus CIN; ▲P < 0.05 versus IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA.

Fig. 3.

Renal morphological changes are worsened after renalase inhibition in CIN rats following limb ischemic preconditioning. Contrast induced nephropathy was induced in rats 24 h after limb ischemic preconditioning and at 24 h after CIN, tissues were collected for further analysis. a. Renal histological alterations by periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining (representative pictures, 400 ×, PAS). b. Tubular injury scoring. Sham, sham-operated control group; CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group without Iimb IPC; CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with scramble siRNA injection; CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with renalase siRNA injection; IPC + CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC; IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with scramble siRNA injection; IPC + CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with renalase siRNA injection. All values are presented as means ± SEM (N = 6). ⁎P < 0.01 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus CIN; ▲P < 0.05 versus IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA.

Fig. 4.

Alterations of renal malondialdehyde and superoxide dismutase levels in CIN rats following limb ischemic preconditioning. Contrast induced nephropathy was induced in rats 24 h after limb ischemic preconditioning and at 24 h after CIN, tissues were collected for further analysis. a. Renal malondialdehyde (MDA). b. Renal superoxide dismutase (SOD). Sham, sham-operated control group; CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group without Iimb IPC; CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with scramble siRNA injection; CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with renalase siRNA injection; IPC + CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC; IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with scramble siRNA injection; IPC + CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with renalase siRNA injection. All values are presented as means ± SEM (N = 6). ⁎P < 0.01 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus CIN; ▲P < 0.05 versus IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA.

Fig. 5.

Renal apoptosis is exacerbated after renalase inhibition in CIN rats following limb ischemic preconditioning. Contrast induced nephropathy was induced in rats 24 h after limb ischemic preconditioning and at 24 h after CIN, tissues were collected for further analysis. a. Renal histological apoptosis by TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling) staining (representative pictures, 400 ×, TUNEL staining). b. Semi-quantitative analysis of number of apoptotic cells per field. c. Renal cleaved-caspase3 expression. Sham, sham-operated control group; CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group without Iimb IPC; CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with scramble siRNA injection; CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with renalase siRNA injection; IPC + CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC; IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with scramble siRNA injection; IPC + CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with renalase siRNA injection. All values are presented as means ± SEM (N = 6). ⁎P < 0.01 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus CIN; ▲P < 0.05 versus IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA.

Fig. 6.

Renal infiltrating macrophages are increased after renalase inhibition in CIN rats following limb ischemic preconditioning. Contrast induced nephropathy was induced in rats 24 h after limb ischemic preconditioning and at 24 h after CIN, tissues were collected for further analysis. a. Renal infiltrated macrophages by CD68 staining (representative pictures, 400 ×, IHC). b. Semi-quantitative analysis of number of CD68-positive cells per field. c. Renal MCP-1 mRNA expression. Sham, sham-operated control group; CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group without Iimb IPC; CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with scramble siRNA injection; CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group with renalase siRNA injection; IPC + CIN, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC; IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with scramble siRNA injection; IPC + CIN + Renalase siRNA, contrast induced nephropathy group following limb IPC with renalase siRNA injection. All values are presented as means ± SEM (N = 6). ⁎P < 0.01 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus CIN; ▲P < 0.05 versus IPC + CIN + Scramble siRNA.

3.2. Limb IPC-mediated reno-protection against CIN is dependent on renalase upregulation

To determine whether renalase would be involved in the reno-protective effects of limb IPC, siRNA was administrated to knock down renal renalase prior to CIN induction. As shown in Fig. S1, siRNA injection led to significant decrease of renalase mRNA and protein expression. We observed that all the aforementioned renal protective effects offered by limb IPC including improvement of renal function and histological injury, were inhibited by renalase downregulation (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6). This suggests that limb IPC induced upregulation of renalase plays a critical role in the reno-protection of limb IPC against CIN.

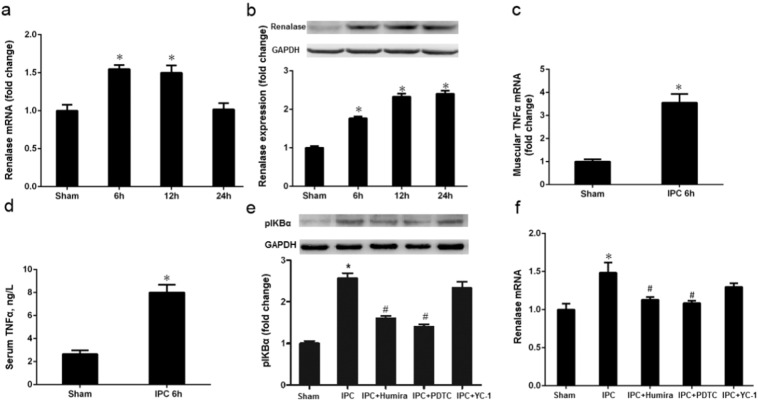

3.3. Limb IPC leads to increased TNFα levels in the muscle and blood, and elevated expression of renal cortical renalase

Both renalase mRNA and protein levels were increased at 6 h (limb IPC vs. Sham, P < 0.05) and 12 h (limb IPC vs. Sham, P < 0.05) and renalase protein also increased at 24 h (limb IPC vs. Sham, P < 0.05) after limb ischemia (Fig. 7a–b). The maximum levels of renalase mRNA and protein were observed at 6 h and 24 h, respectively. Additionally, both muscular TNFα mRNA and serum TNFα were up-regulated at 6 h (limb IPC vs. Sham, P < 0.05) after limb ischemia (Fig. 7c–d).

Fig. 7.

Limb ischemic preconditioning induces renalase via TNFα/NF-κB pathways. Limb ischemic preconditioning (IPC) was delivered by occluding hind limb blood flow with a tightened tourniquet around the upper thigh for 6 cycles of 10-min occlusion followed by 10-min release. a. Kidney renalase mRNA changes at different time points after limb IPC. b. Kidney renalase protein levels at different time points after limb IPC. c. TNFα mRNA at 6 h after limb IPC. d. Serum TNFα level at 6 h after limb IPC. e. Kidney phospho-IκBα (pIκBα) expression at 6 h after limb IPC with TNFα blocking (Humira), NF-κB blocking (PDTC) or HIF-1α blocking (YC-1). f. Kidney renalase expression 6 h after limb IPC with TNFα blocking (Humira), NF-κB blocking (PDTC) or HIF-1α blocking (YC-1). All values are presented as means ± SEM (N = 6).⁎P < 0.05 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus IPC.

3.4. Limb IPC induces renalase up-regulation through activation of the TNFα/NF-κB pathway

Since the maximum expression of renalase mRNA was observed at 6 h after limb ischemia, we carried out a set of experiments at this time point to investigate whether NF-κB and HIF-1 pathways were involved in limb IPC-induced renalase upregulation in the kidney. As shown in Fig. 7f, expression of cortical renalase protein was increased dramatically 6 h after limb ischemia compared with sham-operated animals. Coincidentally, phospho-inhibitor of kappa B (IκBα), as the indicator of activation of NF-κB, was also increased in renal cortex after limb IPC (Fig. 7e). Pretreatment with either Humira (Scheinfeld, 2003), an antagonist of TNFα, or pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PDTC) (Zhou et al., 1999), a specific NF-κB inhibitor, abolished elevation of phospho-IκBα and renalase expression (Fig. 7e and f). In contrast, there was no significant difference in renalase and phospho-IκBα expression in CIN rats subjected to YC-1, a specific HIF-1α inhibitor (Fig. 7e–f). Taken together, these data indicated that activation of NF-κB, but not HIF-1α, was responsible for renalase expression in the kidney after limb IPC. Since limb muscle ischemia can result in the release of TNFα from injured tissue to the blood and this cytokine is able to induce activation of NF-κB and renal renalase synthesis, our data thus suggest that the TNFα/NF-κB pathway may be involved in limb IPC induced renalase upregulation.

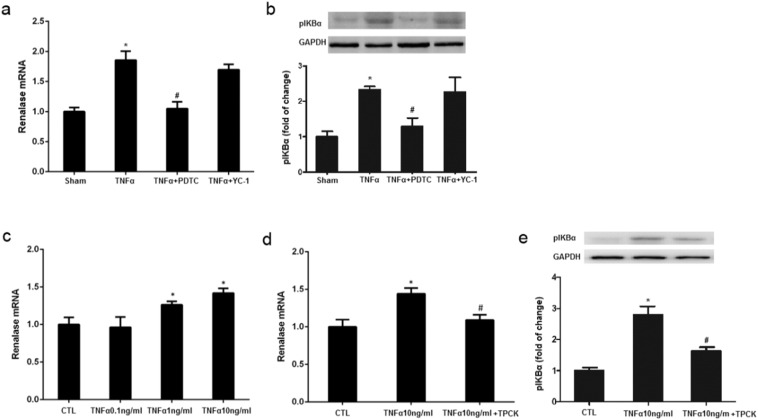

3.5. TNFα preconditioning up-regulates renalase in the kidney via activation of the NF-κB pathway

To directly elucidate the possible role of TNFα in renalase expression and the NF-κB pathway in this process, we further assessed the effect of exogenous TNFα on renal renalase and phospho-IκBα expression in rats and the effect of NF-κB inhibition. Similar to the role of limb IPC, administration of exogenous TNFα also increased expression levels of renalase and phospho-IκBα in the kidney at 6 h. Interestingly, TNFα induced renalase and phospho-IκBα expression were also abolished by PDTC whereas YC-1 treatment did not show any inhibitory effect on expression of these two proteins (Fig. 8a–b). Thus, these data enforces the important role of the TNFα/NF-κB pathway in regulating expression of renal renalase and further suggests TNFα as the intermediator in linking limb IPC to renalase upregulation and subsequent renal protection.

Fig. 8.

TNFα preconditioning induces renalase upregulation via NF-κB pathway. TNFα preconditioning was induced by intravenous injection of TNFα (0.1 μg/kg) in rats. The kidneys were harvested at 6 h after TNFα preconditioning. HK2 cells were exposed to TNFα for 6 h, and renalase expression was assessed. a. Renalase expression induced by limb IPC with TNFα blocking (Humira), NF-κB blocking (PDTC) or HIF-1α blocking (YC-1), ⁎P < 0.05 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus IPC; b. Phospho-IκBα (pIκBα) expression at 6 h after TNFα preconditioning. c. Renalase expression induced by TNFα with NF-κB blocking (PDTC) or HIF-1α blocking (YC-1). ⁎P < 0.05 versus Sham; #P < 0.05 versus TNFα; d. Renalase expression in HK2 under different TNFα concentration, ⁎P < 0.05 versus Control (CTL). e. TPCK blocked TNFα induced renalase upregulation in HK2 cells. ⁎P < 0.05 versus Control (CTL); #P < 0.05 versus TNFα 10 ng/l. All the values depicted are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments.

3.6. TNFα induces renalase expression in proximal renal tubular epithelial cells via activation of NF-κB signaling pathway

To further validate whether TNFα would act on renal tubular cells to provoke renalase expression, we examined the effect of TNFα on renalase and phospho-IκBα expression in cultured HK2 cells, a human renal proximal tubular cell line. HK2 cells were exposed to different concentrations of TNFα for 6 h, and renalase and phospho-IκBα expression were then assessed. In agreement with our animal study, the expression level of renalase and phospho-IκBα in HK2 cells exposed to a low dose of TNFα was higher than those without incubation with this cytokine. Consistently, treatment with tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) (Wang et al., 2014a, Zhou et al., 1999), an inhibitor of NF-κB, also effectively reduced TNFα induced IκBα phosphorylation and renalase expression in this cell type (Fig. 8c–e). As such, we suggest that TNFα can stimulate renal tubular cells to produce renalase though activation of the NF-κB pathway.

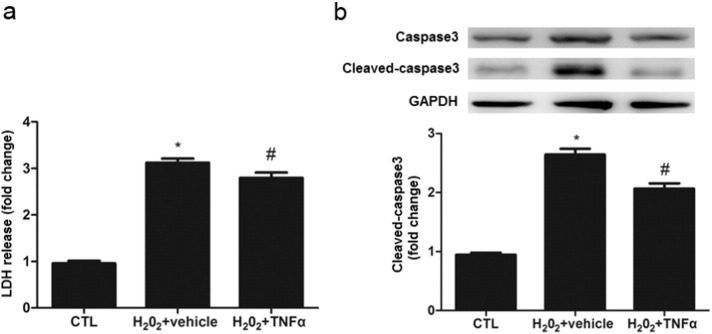

3.7. TNFα preconditioning protects against H2O2 cytotoxicity and apoptosis in HK-2 cells

If TNFα-induced renalase expression is required for renal protection, preincubaton of renal tubular cells with this cytokine should protect against cell death in response to acute injury. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the TNFα preconditioning on H2O2 cytotoxicity in HK-2 cells. HK2 cells were treated with a low dose of TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 6 h followed by exposure of them to H2O2 for an additional 12 h. As shown in Fig. 9, H2O2 exposure led to a remarkable cell death as indicated by increases of LDH release and apoptotic cells in cultures without TNFα preconditioning, whereas TNFα pretreatment significantly decreased LDH release and caspase-3 activity.

Fig. 9.

Low dose of TNFα pretreatment protects against H2O2-induced oxidative injury.

HK-2 cells were pretreated with vehicle or TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 6 h and then were exposed to H202 (300 μm/l) for an additional 12 h. Cells were harvested for measuring LDH release and immunoblot analysis of cleaved caspase-3. a. LDH release; b. cleaved caspase3 expression. ⁎P < 0.05 versus Control (CTL); #P < 0.05 versus TNFα 10 ng/ml. All the value depicted are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that remote IPC (limb IPC) alleviates the subsequent renal injury induced by contrast media through the mechanisms associated with anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammation and anti-oxidation. We also found that the reno-protective effects of limb IPC against CIN are mediated by renalase upregulation. Furthermore, our results indicate that limb IPC induced renalase expression is regulated via the TNFα/NF-κB, but not HIF-1 pathway. Thus, we suggest that remote IPC induced renalase upregulation is critically involved in the reno-protective effect in CIN.

Remote IPC, especially limb IPC, is a harmless, nonpharmacological and effective prevention and treatment strategy for I/R injury in many organs and has been widely used in clinical settings. Recent studies suggest that this approach is also effective for prevention of AKI (Wever et al., 2011) and CIN (Liu et al., 2015). In agreement with previous animal studies (Liu et al., 2015), we found that limb IPC attenuated deterioration of renal function after Ioversol-induced CIN, which was accompanied with reduced cell apoptosis, inflammation and oxidative stress. In addition, renalase, a kidney-derived protein was up-regulated after limb IPC whereas renalase knockdown eliminated the reno-protection of limb IPC as evidenced by our observations that rats pretreated with renalase siRNA exhibited more severe tubular injury and worsen renal function. These results are consistent with our previous study showing that exogenous renalase administration protected CIN through anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis mechanisms (Zhao et al., 2015) and suggest that renalase plays a pivotal role in mediating the reno-protective effect of limb IPC.

Mounting evidence has proved that renalase can mediates cytoprotection via activating survival-associated signaling such as Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Protein kinase B (AKT) (Wang et al., 2014b, Wang et al., 2015d). Recently, it has been reported that inhibition of renalase signaling has antitumor activity in pancreatic cancer and melanoma (Guo et al., 2016). Our previous study also demonstrated that local IPC-elicited beneficial effects on renal I/R injury was partly dependent renalase upregulation, which was associated with decreased apoptosis and oxidative stress. In this study, our findings confirmed that renalase plays an essential role in in remote IPC-elicited reno-protection against CIN, which contributes to a better understanding of the biological properties of renalase. Renalase, up-regulated under both local hypoxia and remote IPC, can promote cell survival and protect against I/R injury.

Currently, the mechanism by which limb IPC induces upregulation of renal renalase is incomplete clear. Given that remote IPC-activated humoral signaling pathways is involved in the remote organ protection (Gassanov et al., 2014), the circulating cytokines released from the preconditioned limb muscle may increase the resistance to hypoxic injury in distant organ (Bonventre, 2012). In this context, several studies have revealed that low dose of TNFα has protective biological properties against ischemic injury and preconditioning with TNFα can mimic classic IPC in a time and dose dependent manner (Lecour et al., 2002, Smith et al., 2002), suggesting that TNFα may serve as a key mediator for limb IPC to induce reno-protection. This hypothesis was supported by the following observations: 1) circulating TNFα increased 6 h after limb IPC, which preceded the expression of renalase in the kidney that occurred at 24 h after limb IPC; 2) Renalase expression was up-regulated in the kidney when exogenous TNFα was administered in the animal; 3) low dose of TNFα treatment increased renalase expression in cultured renal epithelial cells, which is required for cell survival in response to oxidant injury; and 4) administration of Humira, a TNFα antagonist, blocked limb IPC induced renalase upregulation. TNFα may be released from ischemic limb into the systemic circulation and then promotes renalase synthesis in the remote kidney. In line with our observations, other studies have also indicated that low dose of TNFα can protect against I/R injury in heart, liver and neural system (Kleinbongard et al., 2011, Perry et al., 2011, Watters and O'connor, 2011, Feng et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, how TNFα mediates renal protection has not been well defined. It is well known that TNFα is a pleiotropic cytokine involved in the regulation of infection, inflammation, autoimmune, and apoptosis (Pasparakis et al., 1996, Karatzas et al., 2014), thus, this cytokine may play a detrimental role through its pro-inflammatory effects in certain tissues/organs after acute injury. However, since low dose of TNFα can induce activation of multiple signaling pathways that regulate expression/activation of different molecule with diverse biological functions, it is possible that muscular TNFα released during limb IPC may induce activation of a signaling pathway(s) that triggers expression of a protective molecule such as renalase. In this context, we observed that limb IPC-induced renalase upregulation was accompanied by activation of NF-κB signaling in the kidney and pretreatment with either TNFα antagonist (Humira), or NF-κB inhibitor (PDTC), blocked renalase expression. Therefore, the NF-κB signaling pathway may play an essential role in transmitting the renal protective signal from TNFα to expression of some molecules (i.e., renalase) required for renal protection. In support of this hypothesis, activation of the TNFα/NF-κB signaling pathway has been reported to mediate survival of several cell types including cardiomyocytes (Lecour et al., 2005), hepatocytes (Feng et al., 2013) and neuron (Watters et al., 2011) as well as renal tubular cells as indicated in this study. Interesting, it was been reported that low dose of TNFα increased cardiomyocytes' tolerance to toxicity of “high TNFα” (Cacciapaglia et al., 2014). Although we can no rule out the possibility that limb IPC -induced activation of TNFα signaling pathway may also causes a deleterious effect, the protective effect of TNFα/NF-κB signaling observed in the current study suggests that, at least in the case of CIN, the beneficial effects mediated by this pathway overrides its deleterious effects to the kidney. Further investigations are needed to address this issue.

Other molecules and signaling pathways may also be involved in the renal protection after limb IPC. Animal and human studies have revealed that transient limb IPC can lead to a rapid increase of serum EPO (Oba et al., 2015). Increased expression of endogenous EPO or administration of exogenous EPO has been reported to play a protective effect against renal injury induced by diverse stimuli. As such, remote IPC may also induced defense against ischemic injury in kidney through release of EPO from the kidney (Gardner et al., 2014, Diwan et al., 2008). Moreover, it is possible that catecholamines may also play a role in limb IPC-induced renalase upregulation. It has been reported that remote IPC can lead to increased catecholamines levels in myocardial tissue and catecholamines can evoke renalase synthesis (Wang et al., 2014a, Li et al., 2008). In addition, pretreatment with catecholamines can mimic the effect of preconditioning (Bankwala et al., 1994, De Zeeuw et al., 2001). Thus, it will be interesting to further examine, to what extent, various molecules/signaling pathways contribute to the reno-protection after limb IPC and whether they act coordinately to regulate this response.

In summary, this study reveals an important role of endogenous renalase in limb IPC-mediated reno-protection against CIN. Limb IPC may exert its beneficial effects through a humoral signaling pathway by secreting TNFα into the circulation, subsequently activating NF-κB survival signaling in the kidney. This work provides an insight into the mechanisms of limb IPC as well as renalase biogenesis, and lays the groundwork for clinical CIN prevention and treatment with renalase therapy.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

siRNA-mediated renalase knockdown efficacy in vivo. The same volume of vehicle, scramble siRNA or renalase siRNA was injected into the bilateral renal cortex of rats in control, Scramble siRNA and renalase siRNA group, respectively. Kidney tissues were collected for examining renalase mRNA and protein expression 38 h after siRNA injection. a. Knockdown efficacy of renalase mRNA. b. Renal renalase mRNA expression. Control, vehicle injection control group; Scramble siRNA, negative control siRNA injection group; Renalase siRNA, renalase siRNA injection group. All values are presented as means ± SEM (N = 6). ⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001 versus Scramble siRNA.

Authors' Contributions

W.F., W.N., and Z.S. conceived of and designed the experiments. W.F., Y.J., L.Z., and Z.G. performed the experiments. W. F. and T.X analyzed and interpreted the data. W.F., Y.J., and Z.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570603), the New-100 talent Plan of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (2012), Shanghai Talents Development Fund (2013) and Shanghai Pujiang Talent Projects (15PJ1406700). The authors wish to thank Dr. Marc Casati of Medical College of Wisconsin for his advice and revision of the manuscript. Part of this work was submitted to ASN 2015 Kidney Week as an abstract.

Contributor Information

Feng Wang, Email: zyzwq1030@hotmail.com.

Shougang Zhuang, Email: szhuang@lifespan.org.

Niansong Wang, Email: wangniansong2008@163.com.

References

- Asif A., Epstein M. Prevention of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004;44:12–24. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankwala Z., Hale S.L., Kloner R.A. Alpha-adrenoceptor stimulation with exogenous norepinephrine or release of endogenous catecholamines mimics ischemic preconditioning. Circulation. 1994;90:1023–1028. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best P.J., Lennon R., Ting H.H., Bell M.R., Rihal C.S., Holmes D.R., Berger P.B. The impact of renal insufficiency on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002;39:1113–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventre J.V. Limb ischemia protects against contrast-induced nephropathy. Circulation. 2012;126:384–387. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.119701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciapaglia F., Salvatorelli E., Minotti G., Afeltra A., Menna P. Low level tumor necrosis factor-alpha protects cardiomyocytes against high level tumor necrosis factor-alpha: brief insight into a beneficial paradox. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2014;14:387–392. doi: 10.1007/s12012-014-9257-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw S., Lameris T.W., Duncker D.J., Hasan D., Boomsma F., Van Den Meiracker A.H., Verdouw P.D. Cardioprotection in pigs by exogenous norepinephrine but not by cerebral ischemia-induced release of endogenous norepinephrine. Stroke. 2001;32:767–774. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.3.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwan V., Jaggi A.S., Singh M., Singh N., Singh D. Possible involvement of erythropoietin in remote renal preconditioning-induced cardioprotection in rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2008;51:126–130. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31815d88c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M., Huang K., Huang D., Yang L., Gao L., Wang X., Huang D., Li X., Wang C., Zhang F., Wang Y., Cheng M., Tong Q., Qin G., Huang K., Wang L. Renalase is a novel target gene of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in protection against cardiac ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015;105:182–191. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er F., Nia A.M., Dopp H., Hellmich M., Dahlem K.M., Caglayan E., Kubacki T., Benzing T., Erdmann E., Burst V. Ischemic preconditioning for prevention of contrast medium–induced nephropathy randomized pilot RenPro trial (renal protection trial) Circulation. 2012;126:296–303. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R.G., Ince C., Joles J.A., Smith D.W., May C.N., O'connor P.M., Gardiner B.S. Haemodynamic influences on kidney oxygenation: clinical implications of integrative physiology. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013;40:106–122. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng M., Wang Q., Wang H., Guan W. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha preconditioning attenuates liver ischemia/reperfusion injury through preserving sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase function. J. Surg. Res. 2013;184:1109–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner D.S., Welham S.J., Dunford L.J., Mcculloch T.A., Hodi Z., Sleeman P., O'sullivan S., Devonald M.A. Remote conditioning or erythropoietin before surgery primes kidneys to clear ischemia-reperfusion-damaged cells: a renoprotective mechanism? Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2014;306:F873–F884. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00576.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassanov N., Nia A.M., Caglayan E., Er F. Remote ischemic preconditioning and renoprotection: from myth to a novel therapeutic option? J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014;25:216–224. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Hollander L., Macpherson D., Wang L., Velazquez H., Chang J., Safirstein R., Cha C., Gorelick F., Desir G.V. Inhibition of renalase expression and signaling has antitumor activity in pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22996. doi: 10.1038/srep22996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Wang L., Velazquez H., Safirstein R., Desir G.V. Renalase: its role as a cytokine, and an update on its association with type 1 diabetes and ischemic stroke. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2014;23:513–518. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatzas T., Neri A.-A., Baibaki M.-E., Dontas I.A. Rodent models of hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury: time and percentage-related pathophysiological mechanisms. J. Surg. Res. 2014;191:399–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbongard P., Schulz R., Heusch G. TNFalpha in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion, remodeling and heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2011;16:49–69. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecour S., Smith R.M., Woodward B., Opie L.H., Rochette L., Sack M.N. Identification of a novel role for sphingolipid signaling in TNF alpha and ischemic preconditioning mediated cardioprotection. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2002;34:509–518. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecour S., Suleman N., Deuchar G.A., Somers S., Lacerda L., Huisamen B., Opie L.H. Pharmacological preconditioning with tumor necrosis factor-alpha activates signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 at reperfusion without involving classic prosurvival kinases (Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase) Circulation. 2005;112:3911–3918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.581058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.T., Kim J.Y., Kim M., Wang P., Tang L., Baroni S., D'agati V.D., Desir G.V. Renalase protects against ischemic AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013;24:445–455. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012090943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Xu J., Wang P., Velazquez H., Li Y., Wu Y., Desir G.V. Catecholamines regulate the activity, secretion, and synthesis of renalase. Circulation. 2008;117:1277–1282. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Fang Y., Liu S., Yu X., Zhang H., Liang M., Ding X. Limb ischemic preconditioning protects against contrast-induced acute kidney injury in rats via phosphorylation of GSK-3beta. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;81:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikov V.Y., Faubel S., Siegmund B., Lucia M.S., Ljubanovic D., Edelstein C.L. Neutrophil-independent mechanisms of caspase-1- and IL-18-mediated ischemic acute tubular necrosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:1083–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI15623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menting T.P., Sterenborg T.B., De Waal Y., Donders R., Wever K.E., Lemson M.S., Van Der Vliet J.A., Wetzels J.F., Schultzekool L.J., Warle M.C. Remote ischemic preconditioning to reduce contrast-induced nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015;50:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash K., Hafeez A., Hou S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002;39:930–936. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba T., Yasukawa H., Nagata T., Kyogoku S., Minami T., Nishihara M., Ohshima H., Mawatari K., Nohara S., Takahashi J., Sugi Y., Igata S., Iwamoto Y., Kai H., Matsuoka H., Takano M., Aoki H., Fukumoto Y., Imaizumi T. Renal nerve-mediated erythropoietin release confers cardioprotection during remote ischemic preconditioning. Circ. J. 2015;79:1557–1567. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasparakis M., Alexopoulou L., Episkopou V., Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha-deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B.C., Soltys D., Toledo A.H., Toledo-Pereyra L.H. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in liver ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Investig. Surg. 2011;24:178–188. doi: 10.3109/08941939.2011.568594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson P.B., Hansell P., Liss P. Pathophysiology of contrast medium-induced nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A., Riccio E., Andreucci M., Faga T., Ashour M., Di Nuzzi A., Mancini A., Sabbatini M. Role of reactive oxygen species in pathogenesis of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy. Biomed Res. Int. 2013;2013:868321. doi: 10.1155/2013/868321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przyklenk K., Whittaker P. Remote ischemic preconditioning: current knowledge, unresolved questions, and future priorities. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;16:255–259. doi: 10.1177/1074248411409040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihal C.S., Textor S.C., Grill D.E., Berger P.B., Ting H.H., Best P.J., Singh M., Bell M.R., Barsness G.W., Mathew V. Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002;105:2259–2264. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016043.87291.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinfeld N. Adalimumab (HUMIRA): a review. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:375–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendeski M.M. Pathophysiology of renal tissue damage by iodinated contrast media. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011;38:292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlipak M.G., Heidenreich P.A., Noguchi H., Chertow G.M., Browner W.S., Mcclellan M.B. Association of renal insufficiency with treatment and outcomes after myocardial infarction in elderly patients. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002;137:555–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.M., Lecour S., Sack M.N. Innate immunity and cardiac preconditioning: a putative intrinsic cardioprotective program. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002;55:474–482. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Li J., Xing T., Xie Y., Wang N. Serum renalase is related to catecholamine levels and renal function. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2015;19:92–98. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-0951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Velazquez H., Chang J., Safirstein R., Desir G.V. Identification of a receptor for extracellular renalase. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Zhang G., Lu Z., Geurts A.M., Usa K., Jacob H.J., Cowley A.W., Wang N., Liang M. Antithrombin III/SerpinC1 insufficiency exacerbates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Zhang G., Xing T., Lu Z., Li J., Peng C., Liu G., Wang N. Renalase contributes to the renal protection of delayed ischaemic preconditioning via the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015;19:1400–1409. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Cai H., Zhao Q., Xing T., Li J., Wang N. Epinephrine evokes renalase secretion via alpha-adrenoceptor/NF-kappaB pathways in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2014;39:252–259. doi: 10.1159/000355802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Li J., Huang B., Zhao Q., Yu G., Xuan C., Wei M., Wang N. Clinical survey on contrast-induced nephropathy after coronary angiography. Ren. Fail. 2013;35:1255–1259. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.823874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Velazquez H., Moeckel G., Chang J., Ham A., Lee H.T., Safirstein R., Desir G.V. Renalase prevents AKI independent of amine oxidase activity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014;25:1226–1235. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013060665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters O., O'connor J.J. A role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha in ischemia and ischemic preconditioning. J. Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:87. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters O., Pickering M., O'connor J.J. Preconditioning effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and glutamate on calcium dynamics in rat organotypic hippocampal cultures. J. Neuroimmunol. 2011;234:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wever K.E., Warle M.C., Wagener F.A., Van Der Hoorn J.W., Masereeuw R., Van Der Vliet J.A., Rongen G.A. Remote ischaemic preconditioning by brief hind limb ischaemia protects against renal ischaemia-reperfusion injury: the role of adenosine. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011;26:3108–3117. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Zhao Q., Li J., Xing T., Wang F., Wang N. Renalase protects against contrast-induced nephropathy in Sprague-Dawley rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Struthers A.D., Lyles G.A. Differential effects of some cell signalling inhibitors upon nitric oxide synthase expression and nuclear factor-kappaB activation induced by lipopolysaccharide in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol. Res. 1999;39:363–373. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1998.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

siRNA-mediated renalase knockdown efficacy in vivo. The same volume of vehicle, scramble siRNA or renalase siRNA was injected into the bilateral renal cortex of rats in control, Scramble siRNA and renalase siRNA group, respectively. Kidney tissues were collected for examining renalase mRNA and protein expression 38 h after siRNA injection. a. Knockdown efficacy of renalase mRNA. b. Renal renalase mRNA expression. Control, vehicle injection control group; Scramble siRNA, negative control siRNA injection group; Renalase siRNA, renalase siRNA injection group. All values are presented as means ± SEM (N = 6). ⁎⁎⁎P < 0.001 versus Scramble siRNA.