Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections are among the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the world.1 In Peru, among men who have sex with men (MSM) the prevalence of urethral N. gonorrhoeae and/or C. trachomatis infections has been shown to be as high as 5.5%,2 but data regarding extra-genital infections are sparse. To our knowledge only one other study has characterized this disease burden, but in a non-clinic-based population. That study found a prevalence of anal and pharyngeal C. trachomatis infection of 19.0% and 4.8%, respectively, as well as anal and pharyngeal N. gonorrhoeae infection of 9.6% and 6.5%, respectively, among MSM and transgender women in Lima, Peru.3 The lack of published data may be because traditional screening methods are based on urethral swabs and urine specimens, which do not detect extra-genital infections. Previous studies in the United States have shown that more than 70% of extra-genital N. gonorrhoeae infections, and more than 85% of extra-genital C. trachomatis infections were associated with a negative urethral test at the same visit.4 Additionally, screening efforts for extra-genital infections have been noted to be far less than for urethral infections.4

Accurate detection and treatment of extra-genital infection will reduce further transmission as well as associated economic and social impacts of the disease.5] The present study aims to characterize the disease burden of extra-genital C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infections, as well as to identify risk factors for infection, among MSM and transgender women in Lima, Peru, in order to better inform screening efforts.

Methods

This cross-sectional analysis was conducted using baseline data from participants in a cohort study in Lima, Peru between May 2013 and May 2014.6 The study sample on which the cross-sectional analysis was performed consisted of members of the cohort, and included MSM and transgender women presenting for care or testing at one of two sexual health clinics in Lima, Peru. Alberto Barton Clinic is a municipal clinic for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV infection, publicly funded and staffed in Callao, a port city adjacent Lima, Peru. Epicentro is a gay men’s community center and health clinic. Both provide no or very low cost services. Cohort study participants included men who have sex with men or male-to-female transgender women, at least 18 years of age, willing to participate in study procedures, living in Lima with plans to remain, and agreed to provide informed consent. Additionally, since one of the main purposes of the overall study was to investigate syphilis and repeat syphilis infections, to be eligible to join the cohort participants had to have at least three of the following: a positive syphilis rapid test, a positive HIV rapid test, five or more years of sexual activity, five or more sex partners in the past three months, diagnosed with a STD within the last six months, currently reporting an ulcerative STD, or reporting five or more episodes of condomless receptive anal intercourse with a male partner in the past six months.

A structured interview was conducted with each participant by a trained counselor that included questions about sex and gender identity (as reported by each participants), sexual role, alcohol use prior to sexual intercourse, number of male partners in the last three months, history of exchanging money for sex in the prior three months, the use of condoms, and about unmet basic needs (lack of adequate water, food, or shelter, and for how many months in the previous year).

Patients were instructed in proper self-collection of anal swabs, which, in addition to staff-collected pharyngeal swab specimens, were tested using the Aptima Combo 2 for C. trachomatis/N. gonorrhoeae assay (Hologic, San Diego, CA, USA). Because the frequency of asymptomatic urethral infection in males is low (some studies indicating less than 1%),7 we decided not to routinely screen participants for asymptomatic urethral infection. Participants found to be infected were treated according to Peruvian national guidelines.8

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize socio-demographic characteristics and reported behaviors. Bivariate statistics included calculation of prevalence ratios, which were used to examine the association between anal or pharyngeal infections with socio-demographic characteristics and sexual risk behaviors. Multivariate modeling was performed using a full model approach where all variables that had a p value < 0.1 in the bivariate analysis were included in the final model, and adjusted prevalence ratios were reported. Variables accounted for in calculating the adjusted prevalence ratio of anal infections include age, sex role for anal sex, and use of any antibiotic in the past three months. Variables accounted for in calculating the adjusted prevalence ratio of pharyngeal infections include age and sex/gender identity. All analyses were conducted using STATA software version 13 (College Station, TX, USA). Funding for this study came from National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID): 1R01AIO99727. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia with written and informed consent obtained from all patients. UCLA determined that the analysis of de-identified data were exempt from ethical review.

Results

The study sample included 298 MSM and 85 transgender women four participants declined to answer regarding sex/gender identity. The median age of the sample was 29.6 years (interquartile range 23.7–38.4), with an average number of male sex partners of five (interquartile range 2–10) in the past three months. Of the 387 participants, 212 (54.8%) reported a sex identity of gay, and 86 (22.2%) reported bisexual/heterosexual identity. Additionally, of the 387 participants, 205 (53.0%) reported having condomless receptive anal intercourse with a male partner in the past three months. The sample included 116 (30.0%) that reported a history of exchange of sex for money in the past three months.

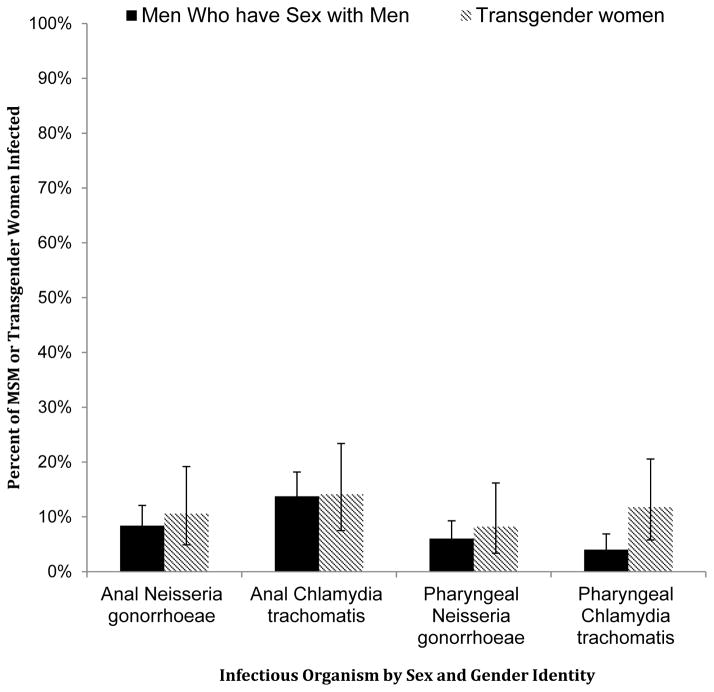

Overall, 127 (32.8%) participants had anal or pharyngeal C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infections. Fifty-three (13.7%) had anal infections with C. trachomatis, while 34 (8.8%) had anal infections with N. gonorrhoeae. Twenty-two (5.7%) participants had pharyngeal infection with C. trachomatis, whereas 25 (6.5%) had pharyngeal infections with N. gonorrhoeae (Figure).

Figure 1.

Percent of men who have sex with men or transgender women infected with either anal or pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis from a clinic-based cohort in Lima, Peru between May 2013 and May 2014.

MSM: men who have sex with men.

Anal infection with N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis was positively associated with practicing both receptive and insertive anal sex, when compared to insertive only (adjusted PR = 2.49; 95% CI = 1.32–4.71), and negatively associated with antibiotic use in the prior three months compared to those with no reported antibiotic use (adjusted PR = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.39–0.91). Pharyngeal infection with N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis was negatively associated with age older than 30 years when compared to age between 18 and 30 years (adjusted PR = 0.54; 95% CI = 0.30–0.96), and positively associated with gender identity of transgender women (adjusted PR = 2.12; 95% CI = 1.20–3.73) (Table).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the prevalence of extra-genital C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infection is considerable among this sample of MSM and transgender women in Lima, Peru. A similarly high burden of infection and associated high incidence was recently reported in a community sample of MSM and transgender women in Lima by Leon et al.3 Explanations for the high rates of infection among MSM and transgender women may be due to a lack of routine screening efforts for extra-genital infections, poor access to STI treatment services, and high rates of sexual risk behaviors.

Other studies have reported risk factors for anal C. trachomatis infections including practicing condomless receptive anal intercourse, and reporting greater numbers of casual sex partners.9,10 Our analysis showed that practicing both receptive and insertive anal intercourse was associated with extra-genital infections in this high-risk population, but we did not find an association between extra-genital infections and the number of sex partners reported. That finding may be because our study population was an inherently high-risk population, in which there were little variance in the number of sexual contacts. Additionally, we found the prevalence of anal C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infection was lower in participants who had used antibiotics in the past three months, which may be due to inadvertent treatment of an undiagnosed infection. A previous study has shown that doxycycline prophylaxis can reduce the incidence of N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis infection.11 Our findings are also in agreement with previous studies, demonstrating that younger age is associated with higher incidence of anal N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis infection,9,10 possibly because younger populations have greater number of sexual contacts, as well as a higher likelihood of infection among those contacts. Pharyngeal C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infection have also been shown to be associated with receptive oral intercourse.12

Previous studies have shown that a history of two prior rectal infections of either C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae is associated with an eightfold increase in the incidence of HIV infection.13 It has been hypothesized that that association is due to risk factors common for HIV and anal C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infections,10 as well as increased biologic susceptibility due to increased cytokine and other inflammatory markers that modulate cell receptors and innate immunity.14⇓–16 Additionally, drug resistant N. gonorrhoeae has been shown to be higher in pharyngeal reservoirs,17⇓–19 and thus there is concern that pharyngeal infections might perhaps serve to promote resistance by facilitating transformation through the transfer of genetic elements between commensal Neisseria species and N. gonorrhoeae in the pharynx of an infected host.18 Therefore, screening and treatment for extra-genital infections with C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae among populations at risk may reduce the incidence of HIV infections and antibiotic resistance, as well as lower the transmission rates of such infections and reduce the overall disease burden.

Currently Peru has no national guidelines specifically recommending extra-genital STI screening. Recent guidelines, however, have been released by the World Health Organization, which includes periodic screening for urethral and anal C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infections as part of the essential STIs package.20 Our findings might inform the next revision of the Peruvian STI treatment guidelines to include routine screening for extra-genital C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infections in high-risk groups.

Important to consider in interpretation of the results of the present study is the difference between heterosexually or bisexually identified men who have sex with men and transgender women. Among transgender women we found higher rates of pharyngeal infection compared to MSM, however, there was no difference between rates of anal infections. Other studies have also found such differences. In Los Angeles, for example, one study demonstrated higher rates of homelessness as well as lower levels of education among transgender women compared to MSM, factors which have been previously associated with increased rates of STIs.21 The sample size in the present study was not large enough for rigorous between-group analyses, and additional research is needed to further characterize precise differences between MSM and transgender women and the risk for extra-genital STIs.

Limitations

One important limitation of this study is that it was done exclusively in a high-risk cohort; therefore the results are not generalizable to the larger population of MSM or transgender women in Lima, Peru, or even those routinely presenting to sexual health clinics in Lima. Additionally, urethral swabs or urine specimens were not collected, so associations between extra-genital and urogenital infections could not be determined. However, the aim of this study was to characterize the burden of infection within this high-risk population, which is not dependent on generalizability nor on association with urogenital infections, and thus the results of this study are still valid.

Conclusion

We found there to be a considerable burden of extra-genital C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infections among high-risk MSM and transgender women in Lima, Peru. Screening programs for extra-genital C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infection should be considered. Further research is necessary to understand the most optimal and cost-effective screening and treatment strategies.

Table 1.

Risk Factors for Pharyngeal and Anal Chlamydial or Gonococcal Infections Among a Clinic-Based Cohort of Men who have Sex with Men and Transgender Women from Lima, Peru between May 2013–May 2014

| Number of Participants with Anal Infection | Prevalence of Anal Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infections | Crude PR | CI | Adjusted PR | CI | Number of Participants with Pharyngeal Infection | Prevalence of Pharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infections | Crude PR | CI | Adjusted PR | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 82/387 | 21% | 45/387 | 12% | ||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18–30 | 50/201 | 25% | Ref | Ref | 29/201 | 14% | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 30+ | 32/186 | 17% | 0.69 | 0.47 – 1.02 | 0.70 | 0.47 – 1.02 | 16/186 | 9% | 0.59 | 0.33 – 1.06 | 0.54 | 0.30 – 0.97 |

| Unmet basic needs (months, last year) | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 31/150 | 21% | Ref | 21/150 | 14% | Ref | ||||||

| 1 – 3 | 27/116 | 23% | 1.13 | 0.71 – 1.78 | 10/116 | 9% | 0.62 | 0.30 – 1.26 | ||||

| 4 – 12 | 24/121 | 20% | 0.96 | 0.60 – 1.55 | 14/121 | 12% | 0.83 | 0.44 – 1.56 | ||||

| Sex identity / Gender Identity* | ||||||||||||

| MSM | 61/298 | 20% | Ref | 29/298 | 10% | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Transgender | 19/85 | 22% | 1.09 | 0.69 – 1.72 | 16/85 | 19% | 1.93 | 1.10 – 3.39 | 2.12 | 1.20 – 3.73 | ||

| Sex role for anal sex | ||||||||||||

| Insertive | 10/87 | 11% | Ref | Ref | 7/87 | 8% | Ref | |||||

| Receptive | 24/123 | 20% | 1.7 | 0.86 – 3.37 | 1.74 | 0.87 – 3.48 | 15/123 | 12% | 1.52 | 0.64 – 3.56 | ||

| Both Insertive and Receptive | 48/177 | 27% | 2.36 | 1.25 – 4.44 | 2.49 | 1.32 – 4.71 | 23/177 | 13% | 1.62 | 0.72 – 3.62 | ||

| Used any antibiotic in past 3 months* | ||||||||||||

| No | 56/229 | 24% | Ref | Ref | 23/229 | 10% | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 25/157 | 16% | 0.65 | 0.43 – 0.99 | 0.6 | 0.39 – 0.91 | 22/157 | 14% | 1.4 | 0.81 – 2.42 | ||

| Used any alcohol before last sexual encounter* | ||||||||||||

| No | 58/267 | 22% | Ref | 29/267 | 11% | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 24/120 | 20% | 0.92 | 0.60 – 1.41 | 2/15 | 13% | 1.23 | 0.69 – 2.17 | ||||

| Number of male sex partners in the past 3 months | ||||||||||||

| 0 – 2 | 26/117 | 22% | Ref | 13/117 | 11% | Ref | ||||||

| 3 – 5 | 25/112 | 22% | 1 | 0.62 – 1.63 | 16/112 | 14% | 1.29 | 0.65 – 2.55 | ||||

| 6 – 10 | 14/65 | 22% | 0.97 | 0.55 – 1.72 | 5/65 | 8% | 0.69 | 0.26 – 1.86 | ||||

| 11+ | 17/93 | 18% | 0.82 | 0.48 – 1.42 | 11/93 | 12% | 1.06 | 0.50 – 2.27 | ||||

| Had condomless receptive sex with a male partner in the past 3 months*† | ||||||||||||

| No | 32/178 | 18% | Ref | 14/116 | 12% | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 50/205 | 24% | 1.36 | 0.91 – 2.02 | 31/267 | 12% | 0.96 | 0.53 – 1.74 | ||||

| History of exchanging money for sex in past 3 months | ||||||||||||

| No | 61/271 | 23% | Ref | 28/271 | 10% | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 21/116 | 18% | 0.8 | 0.51 – 1.26 | 17/116 | 15% | 1.42 | 0.81 – 2.49 | ||||

Has missing values

For pharyngeal infections, this variable refers to performing condomless fellatio with a male partner in the past 3 months, however for anal infections this variable refers to having condomless receptive anal sex with a male partner in the past 3 months

For anal infections, variables accounted for in calculating adjusted prevalence ratios include Age, Sex role for anal sex, and Use of any antibiotic in the past 3 months

For pharyngeal infections, variables accounted for in calculating adjusted prevalence ratios include Age and Sexual identity/Gender identity

PR stands for Prevalence Ratio

CI stands for 95% Confidence Interval

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding for this study came from National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID): 1R01AIO99727. Testing supplies were donated by Hologic.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Brumer AG, Konda KA, Salvatierra HJ, et al. Prevalence of HIV, STIs, and risk behaviors in a cross-sectional community- and clinic-based sample of men who have sex with men (MSM) in Lima, Peru. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59072–e59072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leon SR, Segura E, Konda KA, et al. High prevalences of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in anal and pharyngeal sites among a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in Lima, Peru. BMC Open. 2016;6:e008245–e008245. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patton ME, Kidd S, Llata E, et al. Extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia testing and infection among men who have sex with men–STD surveillance network, United States, 2010–2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1564–1570. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrow RY, Berkel C, Brooks LC, et al. Traditional sexually transmitted disease prevention and control strategies: tailoring for African American communities. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:S30–39. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818eb923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deiss RG, Leon SR, Konda KA, et al. Characterizing the syphilis epidemic among men who have sex with men in Lima, Peru to identify new treatment and control strategies. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:426–426. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell CJ, Golub SA, Cohen DE, et al. Urine-based asymptomatic urethral gonorrhea and chlamydia screening and sexual risk-taking behavior in men who have sex with men in greater Boston. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:205–211. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministerio de Salud. Dirección General de Salud de las Personas Estrategia Sanitaria Nacional Prevenceon y Control de Infecciones de Transmissiôn Sexual y VIH- SIDA -- Guía Nacional de Manejo de Infecciones de Transmissión Sexual. Lima Peru: 2006. [accessed 28 January 2016]. ftp://ftp2.minsa.gob.pe/docconsulta/documentos/dgsp/vihsida/GuiaNacionalITS_Dic2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin F, Prestage GP, Mao L, et al. Incidence and risk factors for urethral and anal gonorrhoea and chlamydia in a cohort of HIV-negative homosexual men: the health in men study. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:113–119. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.021915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillo R, Konda KA, Leon SR, et al. HIV and sexually transmitted infection incidence and associated risk factors among high-risk MSM and male-to-female transgender women in Lima, Peru. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:567–575. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolan RK, Beymer MR, Weiss RE, et al. Doxycycline prophylaxis to reduce incident syphilis among HIV-infected men who have sex with men who continue to engage in high-risk sex: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:98–103. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Templeton DJ, Jin F, Mcnally LP, et al. Prevalence, incidence and risk factors for pharyngeal gonorrhoea in a community-based HIV-negative cohort of homosexual men in Sydney, Australia. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:90–96. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, et al. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:537–543. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahle EM, Bolton M, Hughes JP, et al. Plasma cytokine levels and risk of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) transmission and acquisition: a nested case-control study among HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1451–1460. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naranbhai V, Abdool Karim SS, Altfeld M, et al. Innate immune activation enhances HIV acquisition in women, diminishing the effectiveness of tenofovir microbicide gel. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:993–1001. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masson L, Passmore JA, Liebenberg LJ, et al. Genital inflammation and the risk of HIV acquisition in women. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:260–269. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unemo M, Nicholas RA. Emergence of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and untreatable gonorrhea. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:1401–1422. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unemo M, Shafer WM. Antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: origin, evolution, and lessons learned for the future. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1230:E19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tapsall JW, Ndowa F, Lewis DA, et al. Meeting the public health challenge of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7:821–834. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J, Lo YR, Caceres CF, et al. WHO guidelines for HIV/STI prevention and care among MSM and transgender people: implications for policy and practice. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(7):536–538. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowers JR, Branson CM, Fletcher J, et al. Differences in substance use and sexual partnering between men who have sex with men, men who have sex with men and women and transgender women. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13:629–642. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.564301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]