Abstract

Introduction

Even after placement on the deceased donor waitlist, there are racial disparities in access to kidney transplant. The association between hospitalization, a proxy for health while waitlisted, and disparities in kidney transplant has not been investigated.

Methods

We used United States Renal Data System Medicare-linked data on waitlisted End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) patients between 2005 and 2009 with continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A & B (n=24 581) to examine the association between annual hospitalization rate and odds of receiving a deceased donor kidney transplant. We used multi-level mixed effects models to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR), controlling for individual-, transplant center-, and organ procurement organization-level clustering.

Results

Blacks and Hispanics were more likely than whites to be hospitalized for circulatory system or endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (p<0.001). After adjustment, compared to individuals not hospitalized, patients who were hospitalized frequently while waitlisted were less likely to be transplanted (>2 vs. 0 hospitalizations/year aOR=0.57, p<0.001). Though blacks and Hispanics were more likely to be hospitalized than whites (p<0.001), adjusting for hospitalization did not change estimated racial/ethnic disparities in kidney transplantation.

Conclusions

Individuals hospitalized while waitlisted were less likely to receive a transplant. However, hospitalization does not account for the racial disparity in kidney transplantation after waitlisting.

Introduction

Recent work has identified pre-kidney transplant hospitalization as a factor associated with poor transplant outcomes 1. However, the overall patterns of pre-transplant hospitalizations, particularly as they relate to whether or not end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients receive a kidney transplant, have not been described in depth or examined with regard to racial and ethnic disparities in transplantation.

It has been consistently shown that racial and ethnic disparities exist in accessing renal transplantation. Racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to be listed for a transplant, they are more likely to be listed later, and once waitlisted, they are less likely to be transplanted and more likely to have long waiting times for receiving an organ 2–8. These factors and others are associated with worse health outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities following kidney transplant 9,10. While causes of racial and ethnic disparities prior to being waitlisted have been well studied 11–14, factors associated with disparities after waitlisting are less well understood 8.

Given that racial and ethnic minorities are waitlisted later after starting dialysis than non-Hispanic whites, we hypothesized that these individuals may be sicker when waitlisted and therefore less likely to ultimately receive a transplant. We used hospitalization rate while waitlisted as a surrogate for overall health, as hospitalization rate has been previously associated with severity of illness and lower quality of life 15–17. However, it is possible that hospital utilization may be an indicator of poor access to primary or preventive care. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between hospitalization and receipt of a kidney transplant and to test whether this explained the racial/ethnic disparity in kidney transplantation. This study used a multilevel modeling approach to account for geographic variation by organ procurement organization (OPO) and transplant center.

Methods

Study population and data sources

Adults (aged 18+ years) waitlisted for first renal allograft between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009 who had continuous coverage by Medicare Parts A and B while waitlisted were included in this analysis. Patient data were obtained from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Demographic and clinical information were ascertained via the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence form (CMS-2728), which is completed at the start of ESRD treatment. Transplant data were obtained from the United Network for Organ Sharing forms at the time of waitlisting and transplantation. Data on hospitalizations were obtained from CMS claims data. Neighborhood poverty and education data from the American Community Survey (ACS) data (2005–2010) were linked to patients by residential zip code at the time of ESRD start. Transplant center and OPO aggregate data were obtained from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients annual reports and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network’s National Donor Service Area Dashboard.

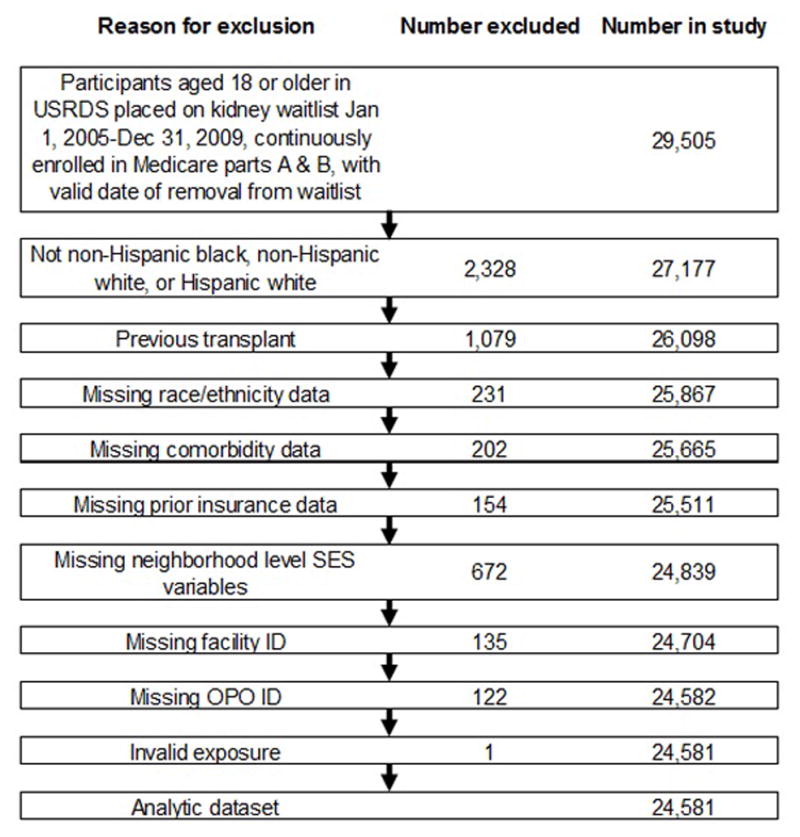

A total of 29 505 adults with ESRD who were waitlisted between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2009 had continuous Medicare coverage while waitlisted and were considered for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they had received a prior transplant, were missing key information, or had invalid hospitalization data. The causes and number of exclusions are outline in Figure 1. The final study population consisted of 24 581 individuals.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study inclusion among ESRD patients waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2009.

Study variables

The primary outcome was receipt of a deceased donor renal transplant after being waitlisted. Study participants were identified at the date of waitlisting and followed until deceased donor transplant, death, removal from the waitlist for other reasons, or the end of the study (December 31, 2009). Individuals who received living donor transplants were considered censored at the time of transplant. Follow-up time was defined as the time from waitlisting until either deceased donor transplant or removal from the waitlist due to death, inactivation, or other causes.

All hospitalizations were counted in the hospitalization rate. The first listed ICD-9 diagnosis code for each hospitalization was regarded as the primary cause of hospitalization and was determined for up to the first 30 hospitalizations. ICD-9 codes were categorized using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s Clinical Classification Software 18.

Race/ethnicity and hospitalization rate while waitlisted were the main exposures of interest in the analysis. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white (referred to as white), non-Hispanic black (referred to as black), and Hispanic white (referred to as Hispanic). Hospitalization rate was measured as the number of hospitalizations per year while waitlisted up to 30 days prior to transplant, to prevent hospitalization associated with the transplant operation from inclusion. Hospitalization rates were divided into three categories: no hospitalizations per year, greater than zero to two hospitalizations per year, and more than two hospitalizations per year. Average length of stay (days) while hospitalized was also examined.

Individual-level covariates included recipient age at waitlisting, peak panel reactive antibody (PRA), sex, blood type, willingness to accept an expanded donor criteria organ, years of dialysis prior to waitlisting, ESRD cause, body mass index (BMI), history of cancer, smoking status, insurance at ESRD start, and employment at ESRD start. Peak PRA was assumed to be the PRA listed as peak, the highest PRA listed, or, if both were missing, was imputed as zero. ESRD cause was categorized as diabetes, hypertension, kidney-related causes (i.e. IgA nephropathy, polycystic kidney disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, or other types of glomerular nephritis), and other causes (e.g. tumor, infection, etc.). Insurance and employment at ESRD diagnosis (i.e. ESRD start) were used as individual-level proxies of socioeconomic status (SES). Insurance and employment at ESRD start were obtained for each individual based on USRDS data. Employment was categorized as employed full-time, employed part-time, unemployed, retired, and other (included homemakers, students, medical leave of absence, and other).

Neighborhood poverty, neighborhood education, and health insurance at the time of ESRD onset were also considered proxies for SES. Neighborhood poverty was estimated by the percentage of households with an annual income below the federal poverty level in each 5-digit zip code area based on ACS data. Neighborhood education was estimated by the percentage of adults with less than a high school level education in each 5-digit zip code area based on ACS data.

Transplant center- and OPO-level covariates included facility renal transplant volume, OPO import-export status for deceased donor renal allografts, and OPO-specific median time to renal transplant. Transplant center renal transplant volume was estimated using the mean number of annual kidney transplants performed between 2005 and 2009 and was divided into tertiles. OPOs were categorized as importers or exporters based on whether they were net receivers of kidneys from other OPOs’ catchment areas or net donors to other OPOs. Median time to transplant was divided into tertiles.

Data analysis

Chi-square and ANOVA tests were used to test for differences between baseline characteristics by race/ethnicity and by hospitalization rate. Chi-square tests were used to examine differences between hospitalization causes by race/ethnicity. Crude time to transplant from waitlisting was examined using Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests were to examine statistical differences by race/ethnicity and hospitalization. We used multi-level logit-binomial models with robust sandwich estimators and fixed and random effects to estimate the odds ratios of receiving a deceased donor transplant, controlling for covariates and accounting for clustering by facility and OPO. The models were adjusted with fixed effects for individual-level demographic and clinical covariates, facility volume, OPO-level covariates and interaction between race/ethnicity and hospitalization rate. Random intercepts were included at the individual, facility, and OPO levels, and a random slope was included for hospitalization rate. The significance of the interaction terms was tested using the likelihood-ratio test and none were significant, thus they were excluded from all further models.

To test for differences between the effects of different types of hospitalizations, a multivariable fixed effects model of the association between hospitalization and transplant was adjusted for fixed effects of average length of hospitalization, hospitalization rate, and cause of hospitalization was constructed. It included a random slope for the effect of hospitalization rate and random intercepts at the individual, transplant center, and OPO levels.

The final multivariable mixed effects model of the association between race/ethnicity and hospitalization on transplant was adjusted for fixed effects of average length of hospitalization, age, sex, blood type, BMI, peak PRA, cause of ESRD, years on dialysis prior to waitlisting, smoking history, cancer history, insurance at time of ESRD start, neighborhood poverty, neighborhood education, transplant center volume, OPO import/export status, and OPO median time to transplant. The model had a random slope for the effect of hospitalization rate and random intercepts at the individual, transplant center, and OPO levels.

As a sensitivity analysis, Cox proportional hazard models were constructed to examine the effects of race/ethnicity on time to transplant with and without adjustment for hospitalization rate and average length of hospitalization and with and without adjustment for age, sex, blood type, BMI, peak PRA, cause of ESRD, years on dialysis prior to waitlisting, smoking history, cancer history, insurance at time of ESRD start, neighborhood poverty, neighborhood education, transplant center volume, OPO import/export status, and OPO median time to transplant. All variables were tested for the proportional hazards assumption using log-log survival curves. Hospitalization rate did not satisfy the proportional hazards assumption, so the models that included this variable were stratified by hospitalization rate.

Complete case analysis was used in all models. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). P-values of <0.05 were considered significant. The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB00038140).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 24 581 adults waitlisted for deceased donor kidney transplant were included in this analysis, of whom 8 504 received a deceased donor transplant (34.62%). Individuals were waitlisted for a median of 418 days (interquartile range (IQR): 166–817.5). During the study period, 2 900 individuals were removed from the waitlist after receiving a living donor transplant (11.81%) and 1 573 were removed from the waitlist because their condition deteriorated and they were no longer eligible or they died (6.40%). The study population was 44.33% white, 35.44% black, and 20.23% Hispanic. Study variables stratified by racial/ethnic group are presented in Table 1. While waitlisted, black individuals were the most likely group to be hospitalized at least once, followed by Hispanics and whites (52.5%, 48.5%, and 44.5%, respectively). Study variables stratified by hospitalization rate are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Distribution of individual-, neighborhood-, transplant center-, and OPO-level study variables stratified by race/ethnicity among ESRD patients waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2009.

| Variable | Total N=24 581 N (%) |

White non-Hispanic N=10 862 N (%) |

Black non-Hispanic N=8 735 N (%) |

White Hispanic N=4 984 N (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean hospitalization rate | |||||

| 0 hosp/yr | 12 795 (52.05) | 6 006 (55.29) | 4 218 (48.29) | 2 559 (51.50) | <0.001 |

| 0< and ≤2 hosp/yr | 7 441 (30.27) | 2 919 (26.87) | 2 917 (33.39) | 1 605 (32.20) | |

| >2 hosp/yr | 4 345 (17.68) | 1 937 (17.83) | 1 597 (18.28) | 811 (16.27) | |

| Average hospitalization length (Mean, SD) | 2.3 (3.9) | 2.2 (4.0) | 2.5 (3.9) | 2.3 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Age at time of waitlisting (Mean, SD) | 54 (13.6) | 57.4 (13.4) | 51.3 (13.2) | 51.4 (13.2) | <0.001 |

| Female | 9 412 (38.29) | 3 849 (35.44) | 3 734 (42.75) | 1 829 (36.70) | <0.001 |

| Blood Type | |||||

| A | 8 163 (33.21) | 4 466 (41.12) | 2 236 (25.60) | 1 461 (29.31) | <0.001 |

| B | 3 463 (14.09) | 1 179 (10.85) | 1 805 (20.66) | 479 (9.61) | |

| AB | 1 007 (4.10) | 430 (3.96) | 457 (5.23) | 120 (2.41) | |

| O | 11 948 (48.61) | 4 787 (44.07) | 4 237 (48.51) | 2 924 (58.67) | |

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 10 799 (43.93) | 4 345 (40.00) | 4 425 (50.66) | 2 029 (40.71) | <0.001 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 3 710 (15.09) | 1 835 (16.89) | 1 002 (11.47) | 873 (17.52) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 4 619 (18.79) | 2 169 (19.97) | 1 377 (15.76) | 1 073 (21.53) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 5 453 (22.18) | 2 513 (23.14) | 1 931 (22.11) | 1 009 (20.24) | |

| Peak PRA | |||||

| PRA=0 | 15 516 (63.12) | 7 134 (65.68) | 5 043 (57.73) | 3 339 (66.99) | <0.001 |

| 0<PRA<80 | 7 346 (29.88) | 3 094 (28.48) | 2 934 (33.59) | 1 318 (26.44) | |

| PRA ≥80 | 1 719 (6.99) | 634 (5.84) | 758 (8.68) | 327 (6.56) | |

| Insurance at ESRD start | |||||

| Employer/Private | 5 739 (23.35) | 2 830 (26.05) | 2 218 (25.39) | 691 (13.86) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 6 472 (26.33) | 1 912 (17.60) | 2 575 (29.48) | 1 985 (39.83) | |

| Medicare | 5 976 (24.31) | 3 763 (34.64) | 1 548 (17.72) | 665 (13.34) | |

| No insurance | 3 875 (15.76) | 1 199 (11.04) | 1 563 (17.89) | 1 113 (22.33) | |

| Other | 2 519 (10.25) | 1 158 (10.66) | 831 (9.51) | 530 (10.63) | |

| Employment at ESRD start | |||||

| Full-time | 3 108 (21.71) | 1 374 (20.31) | 1 045 (23.32) | 689 (22.44) | <0.001 |

| Part-time | 737 (5.15) | 395 (5.84) | 223 (4.98) | 119 (3.88) | |

| Retired | 6 566 (45.86) | 3 625 (53.58) | 1 787 (39.88) | 1 154 (37.59) | |

| Unemployed | 3 120 (21.79) | 1 036 (15.31) | 1 234 (27.54) | 850 (27.69) | |

| Other | 785 (5.48) | 335 (4.95) | 192 (4.28) | 258 (8.40) | |

| Expanded criteria donora | 13 503 (54.93) | 6 271 (57.73) | 4 584 (52.48) | 2 648 (53.13) | <0.001 |

| Years on dialysis at waitlisting | |||||

| 0 | 10 949 (44.54) | 4 503 (41.46) | 4 431 (50.73) | 2 015 (40.43) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 7 047 (28.67) | 3 623 (33.35) | 1 935 (22.15) | 1 489 (29.88) | |

| 2 | 4 195 (17.07) | 1 794 (16.52) | 1 446 (16.55) | 955 (19.16) | |

| 3+ | 2 390 (9.72) | 942 (8.67) | 923 (10.57) | 525 (10.53) | |

| ESRD Cause | |||||

| Diabetes | 9 532 (38.78) | 3 712 (34.17) | 3 152 (36.08) | 2 668 (53.53) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 6 342 (25.80) | 2 219 (20.43) | 3 179 (36.39) | 944 (18.94) | |

| Kidney-related | 4 670 (19.00) | 2 664 (24.53) | 1 251 (14.32) | 755 (15.15) | |

| Other | 4 037 (16.42) | 2 267 (20.87) | 1 553 (13.20) | 617 (12.38) | |

| History of Cancer | 797 (3.24) | 537 (4.94) | 189 (2.16) | 68 (1.36) | <0.001 |

| Cigarette smoker | 1 250 (5.09) | 696 (6.41) | 442 (5.06) | 112 (2.25) | <0.001 |

| % households below poverty line | |||||

| <10% | 206 (0.84) | 100 (0.92) | 76 (0.87) | 30 (0.60) | 0.256 |

| 10%–20% | 5 338 (21.72) | 2 374 (21.86) | 1 866 (21.36) | 1 098 (22.03) | |

| ≥20% | 19 037 (77.45) | 8 388 (77.22) | 6 793 (77.77) | 3 856 (77.37) | |

| % adults with high school education | |||||

| <85% | 11 792 (47.97) | 5 174 (47.63) | 4 159 (47.61) | 2 459 (49.34) | 0.097 |

| ≥85% | 12 789 (52.03) | 5 688 (52.37) | 4 576 (52.39) | 2 525 (50.66) | |

| Mean annual transplant center volume | |||||

| Lowest tertile | 8 359 (34.01) | 3 991 (36.74) | 2 436 (27.89) | 1 932 (38.76) | <0.001 |

| Middle tertile | 8 105 (32.97) | 3 234 (29.77) | 3 358 (38.44) | 1 513 (30.36) | |

| Highest tertile | 8 117 (33.02) | 3 637 (33.48) | 2 941 (33.67) | 1 539 (30.88) | |

| OPO kidney importer | 7 872 (32.02) | 3 287 (30.26) | 3 469 (39.85) | 1 103 (22.19) | <0.001 |

| OPO median wait time to transplant | |||||

| Lowest tertile | 8 322 (33.86) | 4 246 (39.09) | 2 768 (31.68) | 1 308 (26.24) | <0.001 |

| Middle tertile | 8 011 (32.59) | 3 998 (36.81) | 2 939 (33.65) | 1 074 (21.55) | |

| Highest tertile | 8 248 (33.55) | 2 618 (24.10) | 3 028 (34.67) | 2 602 (52.21) | |

All values N (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; OPO, organ procurement organization; hosp/yr, hospitalizations per year; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Willing to accept expanded criteria donor organ.

Table 2.

Distribution of individual-, neighborhood-, transplant center-, and OPO-level study variables stratified by hospitalization rate among ESRD patients waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2009.

| Variable | Total N=24 581 N (%) |

0 Hosp/yr N=12 795 N (%) |

>0 and ≤2 Hosp/yr N=7 441 N (%) |

>2 Hosp/yr N=4 345 N (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White non-Hispanic | 10 862 (44.19) | 6 006 (46.94) | 2 919 (39.23) | 1 937 (44.58) | <0.001 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 8 735 (35.54) | 4 221 (32.99) | 2 917 (39.20) | 1 597 (36.75) | |

| White Hispanic | 4 984 (20.28) | 2 568 (20.07) | 1 605 (21.57) | 811 (18.67) | |

| Average hospitalization length (Mean, SD) | 2.3 (3.88) | 0 (0) | 4.4 (4.32) | 5.6 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Age at time of waitlisting (Mean, SD) | 54 (13.61) | 53.9 (13.71) | 54.2 (13.43) | 54.2 (13.59) | 0.225 |

| Female | 9 412 (38.29) | 4 475 (34.97) | 3 039 (40.84) | 1 898 (43.68) | <0.001 |

| Blood Type | |||||

| A | 8 163 (33.21) | 4 466 (34.90) | 2 290 (30.78) | 1 407 (32.38) | <0.001 |

| B | 3 463 (14.09) | 1 697 (13.26) | 1 142 (15.35) | 624 (14.36) | |

| AB | 1 007 (4.10) | 592 (4.63) | 229 (3.08) | 186 (4.28) | |

| O | 11 948 (48.61) | 6 040 (47.21) | 3 780 (50.80) | 2 128 (49.98) | |

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 10 799 (43.93) | 4 897 (38.27) | 3 864 (51.93) | 2 038 (46.90) | <0.001 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 3 710 (15.09) | 2 142 (16.74) | 935 (12.57) | 633 (14.57) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 4 619 (18.79) | 2 685 (20.98) | 1 165 (15.66) | 769 (17.70) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 5 453 (22.18) | 3 071 (24.00) | 1 477 (19.85) | 905 (20.83) | |

| Peak PRA | |||||

| PRA=0 | 15 516 (63.12) | 8 752 (68.40) | 4 184 (56.23) | 2 580 (59.38) | <0.001 |

| 0<PRA<80 | 7 346 (29.88) | 3 422 (26.74) | 2 576 (34.62) | 1 348 (31.02) | |

| PRA ≥80 | 1 719 (6.99) | 621 (4.85) | 681 (9.15) | 417 (9.60) | |

| % households below poverty line | |||||

| <10% | 206 (0.84) | 116 (0.91) | 57 (0.77) | 33 (0.76) | 0.691 |

| 10%–20% | 5 338 (21.72) | 2 803 (21.91) | 1 595 (21.44) | 940 (21.63) | |

| ≥20% | 19 037 (77.45) | 9 976 (77.19) | 5 789 (77.80) | 3 372 (77.61) | |

| % adults with high school education | |||||

| <85% | 12 789 (52.03) | 6 611 (51.67) | 3 881 (52.16) | 2 297 (52.87) | 0.381 |

| ≥85% | 11 792 (47.97) | 6 184 (48.33) | 3 560 (47.84) | 2 048 (47.13) | |

| Insurance at ESRD start | |||||

| Employer/Private | 5 739 (23.35) | 3 250 (25.40) | 1 613 (21.68) | 876 (20.16) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 6 472 (26.33) | 2 986 (23.34) | 2 094 (28.14) | 1 392 (32.04) | |

| Medicare | 5 976 (24.31) | 2 944 (23.01) | 1 891 (25.41) | 1 141 (26.26) | |

| No insurance | 3 875 (15.76) | 2 162 (16.90) | 1 139 (15.31) | 574 (13.21) | |

| Other | 2 519 (10.25) | 1 453 (11.36) | 704 (9.46) | 362 (8.33) | |

| Employment at ESRD start | |||||

| Full-time | 3 108 (21.71) | 1 942 (23.65) | 724 (19.64) | 442 (18.27) | <0.001 |

| Part-time | 737 (5.15) | 458 (5.58) | 173 (4.69) | 106 (4.38) | |

| Retired | 6 566 (45.86) | 3 634 (44.26) | 1 737 (47.11) | 1 195 (49.40) | |

| Unemployed | 3 120 (21.79) | 1 724 (21.00) | 854 (23.16) | 542 (22.41) | |

| Other | 785 (5.48) | 452 (5.51) | 199 (5.40) | 134 (5.54) | |

| Expanded criteria donora | 13 503 (54.93) | 6 922 (54.10) | 4 173 (56.08) | 2 408 (55.42) | 0.019 |

| Years on dialysis at waitlisting | |||||

| 0 | 10 949 (44.54) | 5 041 (39.40) | 3 888 (52.25) | 2 020 (46.49) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 7 047 (28.67) | 3 868 (30.23) | 1 971 (26.49) | 1 208 (27.80) | |

| 2 | 4 195 (17.07) | 2 370 (18.52) | 1 113 (14.96) | 712 (16.39) | |

| 3+ | 2 390 (9.72) | 1 516 (11.85) | 469 (6.30) | 405 (9.32) | |

| ESRD Cause | |||||

| Diabetes | 9 532 (38.78) | 4 434 (34.65) | 3 039 (40.84) | 2 059 (47.39) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 6 342 (25.80) | 3 436 (26.85) | 1 973 (26.52) | 933 (21.47) | |

| Kidney-related | 4 670 (19.00) | 2 713 (21.20) | 1 306 (17.55) | 651 (14.98) | |

| Other | 4 037 (16.42) | 2 212 (17.29) | 1 123 (15.09) | 701 (16.16) | |

| History of Cancer | 797 (3.24) | 454 (3.55) | 195 (2.62) | 148 (3.41) | 0.001 |

| Cigarette smoker | 1 250 (5.09) | 614 (4.80) | 381 (5.12) | 255 (5.87) | 0.021 |

| Mean annual transplant center volume | |||||

| Lowest tertile | 8 359 (34.01) | 4 412 (34.48) | 2 438 (32.76) | 1 509 (34.73) | <0.001 |

| Middle tertile | 8 105 (32.97) | 4 307 (33.66) | 2 426 (32.60) | 1 372 (31.58) | |

| Highest tertile | 8 117 (33.02) | 4 076 (31.86) | 2 577 (34.63) | 1 464 (33.69) | |

| OPO kidney importer | 7 872 (32.02) | 4 155 (32.47) | 2 390 (32.12) | 1 327 (30.54) | 0.061 |

| OPO median wait time to transplant | |||||

| Lowest tertile | 8 322 (33.86) | 4 707 (36.79) | 2 186 (29.38) | 1 429 (32.89) | <0.001 |

| Middle tertile | 8 011 (32.59) | 4 234 (33.09) | 2 407 (32.35) | 1 370 (31.53) | |

| Highest tertile | 8 248 (33.55) | 3 854 (30.12) | 2 848 (38.27) | 1 546 (35.58) | |

All values N(%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; OPO, organ procurement organization; hosp/yr, hospitalizations per year; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Willing to accept expanded criteria donor organ.

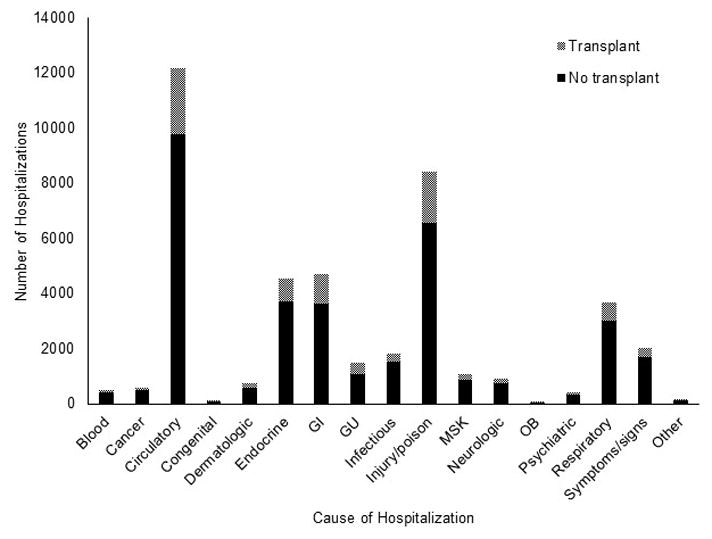

Overall, there were 43 484 hospitalizations for which primary diagnoses were obtained. The most common cause of hospitalization was for diseases of the circulatory system (12 191 hospitalizations, 28.0%), followed by injuries and poisonings (8 441 hospitalizations, 19.4%) and diseases of the digestive system (4 691 hospitalizations, 10.8%). Of all diagnoses, 8 621 (19.8%) were from individuals who received a transplant during the study period. The number of hospitalizations stratified by cause and transplantation are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of primary cause of hospitalization categorized according to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Clinical Classifications Software for ICD-9, stratified by transplant status among ESRD patients waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2009.

Abbreviations and contractions: Blood: Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs; Circulatory: Diseases of the circulatory system; Endocrine: Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases and immunity disorders; GI: Diseases of the digestive system; GU: Diseases of the genitourinary system; MSK: Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue; OB: Complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium; Other: Residual codes, unclassified; Symptoms/signs: Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions and factors influencing health status.

Causes of hospitalization varied by race/ethnicity. The greatest differences in prevalence of hospitalizations by cause were for circulatory system and endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases. Black and Hispanic individuals were more likely than whites to be hospitalized for both causes (both p<0.001, Supplementary Table 1). There were significant differences between racial/ethnic groups in the prevalence of hospitalization for all types of causes except for diseases of the blood and blood forming organs, mental illness, diseases of the nervous system and sense organs, and diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (Supplementary Table 1).

Transplant access by hospitalization cause

After controlling for hospitalization rate and length of stay in the multivariable mixed effects model with hospitalization causes as fixed effects, many hospitalization causes were associated with decreased likelihood of transplant. Hospitalization for neoplasms was associated with the greatest decrease in the odds of being transplanted (OR=0.48, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39–0.60), followed by hospitalization for uncategorized codes (OR=0.55, 95% CI 0.33–0.91) and diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs (OR=0.63, 95% CI 0.46–0.85). Hospitalizations for mental illness, genitourinary, digestive system, obstetric, and congenital conditions were not associated with decreased likelihood of transplant (all p>0.10). Full results for association between hospitalization cause and likelihood of transplant are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Transplant access by race/ethnicity and hospitalization rate (crude analyses)

During the study period, 39.36% of white individuals received deceased donor transplants compared to 33.41% of black and 26.36% of Hispanic individuals (p<0.001). In crude analyses, black and Hispanic individuals who did receive transplants waited longer than white individuals (p<0.001, data not shown). The median waiting time for white individuals who received a transplant was 296 days (IQR: 108–593). For black individuals it was 423 days (IQR: 169–766.5). For Hispanic individuals it was 430 days (IQR: 175–776).

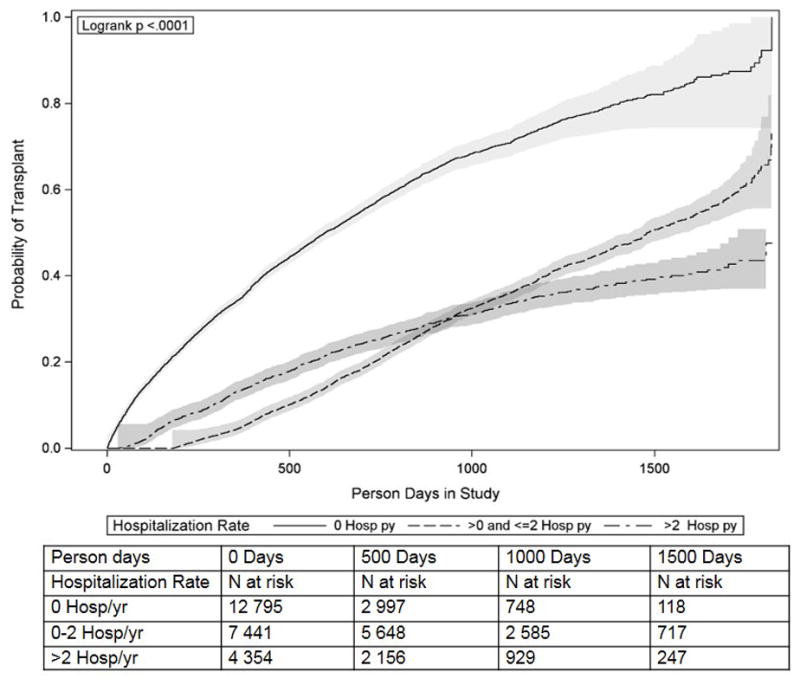

In crude analyses, hospitalization rate while waitlisted was negatively associated with receiving a deceased donor transplant (p<0.001). Never hospitalized individuals were most likely to receive a transplant, compared with those hospitalized >0 and ≤2 times and >2 times per year (40.27%, 32.07%, and 22.22%, respectively). In Kaplan-Meier analysis, the association between hospitalization rate and waiting time was nonlinear, though individuals who were never hospitalized spent less time on the waiting list were more likely to receive a transplant than individuals who were hospitalized (Figure 2, p<0.001). Of the three categories of hospitalization, individuals who were never hospitalized had the shortest median waiting time from wait listing to transplant of 210 days (IQR: 70–457), individuals hospitalized >0 and ≤2 times per year had the longest median waiting time of 707 days (IQR: 457–977), and individuals hospitalized more than two times per year had a median waiting time of 356.5 days (IQR: 170–619.5).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier time to transplant curves by hospitalization rate among ESRD patients waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2009.

Death and inactivation or removal from the waitlist for other reasons were more common among individuals with higher hospitalization rates. Of the study population, 0.22% of individuals who were never hospitalized died while waitlisted during the study, 0.43% of individuals who were hospitalized >0 and ≤2 times/year died, and 2.05% of individuals hospitalized >2 times/year died while waitlisted during the study. Of individuals who were never hospitalized, 1.22% were permanently inactivated or removed from the waitlist because they were too sick to transplant, compared with 7.28% of individuals hospitalized >0 and ≤2 times/year and 16.90% of individuals hospitalized >2 times/year. There were no notable differences in the death rate while waitlisted for different racial/ethnic groups. Of the study population, whites had the highest proportion of individuals who died while waitlisted, followed by blacks and Hispanics (0.73%, 0.57%, and 0.38%, respectively). A similar proportion of blacks and Hispanics were removed or inactivated because they became too sick to transplant (4.62% and 4.77%), but a larger proportion of whites were inactivated or removed from the waitlist for this reason (7.22%).

Transplant access by race/ethnicity and hospitalization rate (multivariable analysis)

The final, fully adjusted multivariable mixed effects model only accounted for some of the racial/ethnic disparity observed between black and white individuals (Table 3, adjusted OR for transplant among black vs. white=0.87, 95% CI 0.81–0.94; unadjusted OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.73–0.82). The fully adjusted model did account for the racial/ethnic disparity between Hispanic individuals and white individuals in transplant (Table 3, adjusted OR for transplant among Hispanic vs. white individuals=0.95, 95% CI 0.86–1.05; unadjusted OR=0.55, 95% CI 0.51–0.59). However, controlling for hospitalization did not change the estimated crude disparity between black individuals and white individuals or between Hispanic and white individuals or the estimated adjusted disparity between black and white individuals (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for association between race/ethnicity and transplant and hospitalization and transplant among ESRD patients waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2009.

| Model 1 OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

Model 4 OR (95% CI) |

Model 5 OR (95% CI) |

Model 6 OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black v. white (ref.) | 0.77 (0.73, 0.82) | -- | 0.78 (0.74, 0.83) | 0.84 (0.78, 0.91) | 0.87 (0.81, 0.94) | 0.87 (0.81, 0.94) |

| Hispanic v. white (ref.) | 0.55 (0.51, 0.59) | -- | 0.54 (0.51, 0.59) | 0.87 (0.79, 0.96) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.09) | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) |

| 0< and ≤2 v. 0 Hosp/yr (ref.) | -- | 0.70 (0.66, 0.74) | 0.71 (0.67, 0.76) | -- | -- | 1.01 (0.87, 1.16) |

| >2 v. 0 Hosp/yr (ref.) | -- | 0.42 (0.39, 0.46) | 0.42 (0.39, 0.45) | -- | -- | 0.57 (0.49, 0.65) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; black, black non-Hispanic; white, white non-Hispanic; Hispanic, white Hispanic; Hosp/yr, mean hospitalizations per year; v., versus; ref., referent; BMI, body max index; PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Model 1: unadjusted except for fixed effect for race/ethnicity and random intercept for individual

Model 2: unadjusted except for fixed effect for hospitalization rate and random intercept for individual

Model 3: unadjusted except for fixed effects for race/ethnicity, hospitalization rate, and random intercept for individual

Model 4: unadjusted except for fixed effect for race/ethnicity and random intercepts for individual, transplant center, and OPO

Model 5: adjusted for fixed effects for race/ethnicity, age, sex, blood type, BMI, peak PRA, cause of ESRD, years on dialysis prior to waitlisting, smoking history, cancer history, insurance at time of ESRD start, willingness to accept an expanded donor criteria organ, neighborhood poverty, neighborhood education, transplant center volume, OPO import/export status, and OPO median time to transplant and random intercepts for individual, transplant center, and OPO.

Model 6: adjusted for variables in Model 5 plus fixed effects for hospitalization rate and average length of hospitalization and a random slope for hospitalization rate.

The variables with the largest impact on the estimated racial/ethnic disparity in transplant were transplant center and OPO (Table 3). Controlling for both transplant center and OPO attenuated the estimated OR for a Hispanic individual compared to a white individual from 0.55 (95% CI: 0.51–0.59) to 0.87 (95% CI: 0.79–0.96) and for a black individual compared to a white individual from 0.77 (95% CI: 0.73–0.82) to 0.84 (95% CI: 0.78–0.91, Table 3), although Hispanics and blacks were still statistically significantly less likely to receive a transplant compared with white individuals.

The associations between other variables and transplant in the fully adjusted model are presented in Table 4. In the fully adjusted model, some variables that were associated with increased odds of transplant included having type A or AB blood (ref=type O; ORs=1.72 and 3.56, respectively; both p<0.0001) and willingness to accept an expanded donor criteria organ (OR=1.60, p<0.0001). Some factors associated with decreased odds of receiving a transplant included years spent on dialysis prior to waitlisting (one year OR=0.67, p<0.0001) and being listed in an OPO with a high median time to transplant (tertile OR=0.49, p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Table of adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for association between variables and likelihood of transplant among ESRD patients waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2009.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Mean hospitalization rate | ||

| 0 hosp/yr | Ref. | |

| >0 and ≤2 hosp/yr | 1.01 (0.87, 1.16) | 0.873 |

| >2 hosp/yr | 0.57 (0.49, 0.65) | <0.001 |

| Average length of hospitalization (days) | 0.92 (0.90, 0.93) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | Ref. | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 0.87 (0.81, 0.94) | <0.001 |

| White Hispanic | 0.95 (0.86, 1.05) | 0.303 |

| Peak PRA | ||

| PRA=0 | Ref. | |

| PRA >0 and <80 | 1.12 (1.00, 1.25) | 0.045 |

| PRA ≥80 | 1.14 (0.92, 1.41) | 0.295 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–40 | Ref. | |

| 41–55 | 1.12 (1.03, 1.22) | 0.002 |

| 56–69 | 1.07 (0.95, 1.20) | 0.157 |

| 70–90 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.18) | 0.453 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref. | |

| Female | 0.91 (0.85, 0.98) | 0.028 |

| Blood type | ||

| O | Ref. | |

| A | 1.72 (1.59, 1.87) | <0.001 |

| B | 0.98 (0.87, 1.09) | 0.982 |

| AB | 3.56 (3.02, 4.20) | <0.001 |

| Neighborhood poverty | 1.00 (0.94, 1.08) | 0.087 |

| Neighborhood education | 1.06 (0.99, 1.14) | 0.549 |

| Insurance at ESRD start | ||

| Private | Ref. | |

| Medicaid | 1.01 (0.91, 1.11) | 0.958 |

| Medicare | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) | 0.965 |

| Other insurance | 0.99 (0.87, 1.13) | 0.831 |

| None | 1.01 (0.87, 1.17) | 0.922 |

| Willing to accept expanded criteria donor organ | 1.60 (1.45, 1.76) | <0.001 |

| Years on dialysis prior to waitlisting | 0.67 (0.63, 0.73) | <0.001 |

| ESRD cause | ||

| Other | Ref. | |

| Diabetes | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) | 0.096 |

| Hypertension | 0.98 (0.87, 1.10) | 0.759 |

| Kidney-related | 1.07 (0.96, 1.20) | 0.221 |

| BMI | ||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | Ref. | |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 1.36 (1.12, 1.67) | 0.003 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 0.90 (0.83, 0.99) | 0.064 |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 0.80 (0.73, 0.88) | <0.001 |

| History of Cancer | 0.75 (0.62, 0.90) | 0.005 |

| Smoker | 0.92 (0.79, 1.06) | 0.386 |

| Transplant center volume | 0.98 (0.88, 1.09) | 0.933 |

| OPO kidney importer | 1.09 (0.85, 1.40) | 0.482 |

| OPO median time to transplant | 0.49 (0.41, 0.58) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; hosp/yr, hospitalizations per year; Ref., referent group; PRA, panel reactive antibody; BMI, body mass index; OPO, organ procurement organization.

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis, Cox proportional hazards models indicated that controlling for hospitalization rate did not eliminate the racial/ethnic disparities in time to transplant (hazard ratio (HR) for black vs. white individuals in fully adjusted model without controlling for hospitalization rate and length of stay=0.80 [95% CI: 0.76–0.84], with hospitalization rate and length of stay=0.80 [0.76–0.84]; for Hispanics compared to whites without adjusting for hospitalization variables HR=0.75 [0.70–0.80], and with, HR=0.72 [0.67–0.77]).

Discussion

In this cohort of US adults waitlisted for deceased donor kidney transplant, the cause of hospitalization had differential effects on the likelihood of transplant and varied by race/ethnicity. Black and Hispanic individuals were more likely to be hospitalized while waitlisted than whites and were more likely to be hospitalized for diseases of the circulatory system and for endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases. On average when hospitalized, blacks had longer lengths of hospitalization than whites or Hispanics. In our sample, black and Hispanic individuals were younger than whites, and younger individuals have been reported to have higher rates of hospitalization pre-transplant than older individuals 19. However the observed association between age and hospitalization was smaller than our observed association between minority race/ethnicity and hospitalization, suggesting that other factors besides age may be involved in the association between race/ethnicity and hospitalization.

This is the first study to investigate causes of hospitalization among racial/ethnic minorities waitlisted for kidney transplant. Earlier work has only considered hospitalization post-transplant 20. We found that there are racial/ethnic differences in causes of hospitalization while waitlisted, consistent with differences in underlying comorbidities. Black and Hispanic individuals were more likely than whites to be hospitalized for circulatory system or endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic illnesses (Supplementary Table 1) and were more likely to have ESRD as a result of similar conditions (Table 1). Hospitalization for either of these causes was associated with a 20% decrease in the odds of receiving a transplant during the study period (Supplementary Table 2). This suggests that differential disease profiles between racial/ethnic groups may lead to differential rates of transplantation.

In prior studies, black race has been associated with higher rates of hospital readmission among Medicare beneficiaries with a variety of conditions 21–24 and higher rates of readmission following kidney transplant 25. Yet among individuals on hemodialysis, black race and Hispanic ethnicity have been associated with lower rates of hospitalization overall, when compared to non-Hispanic whites 26. Part of the discrepancy between this study and the study by Yan, et al. may be that Yan, et al. only considered hospitalization outcomes within the first year of maintenance hemodialysis for ESRD, regardless of waitlisting. There also may be discrepancies because of differences in the age distributions between their study and ours, with individuals in the Yan study being older on average than individuals in our study.

Our hypothesis that racial/ethnic disparities in transplant for waitlisted individuals was partially due to hospitalization was not supported by our results. As previously reported by other researchers, we identified racial differences in the likelihood of transplantation after waitlisting 8,27, but these racial differences were not explained by higher hospitalization rates among minorities. Controlling for hospitalization in crude and adjusted analyses had little to no impact on the estimated racial/ethnic disparities in transplantation. While high rates of hospitalization while waitlisted were associated with lower likelihood of transplant, this effect was independent of race/ethnicity.

The observed racial/ethnic disparities in transplant access were largely explained by center and OPO-level effects, though they did not account for all the observed racial/ethnic disparities. Prior research has underscored the importance of geographic factors in explaining disparities in transplantation 27–30. An interesting result from our study was that controlling for transplant center and OPO nearly eliminated the disparity in transplant between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white individuals (Table 3). This dramatic effect reinforces the fact that region plays a substantial role in likelihood of receiving a transplant for Hispanic individuals and supports similar findings by Arce, et al. 27. Future research should consider regional-level interventions that may make kidney transplantation more equitable across OPOs.

In contrast to the effect of controlling for transplant center and OPO on the disparities in transplant for Hispanic individuals, controlling for these factors had a much smaller impact on the disparity between blacks and whites, underscoring the important fact that racial/ethnic disparities are not homogeneous across groups. Even after full adjustment for individual-, transplant center-, and OPO-level variables, there was still a 13% difference between black individuals’ and white individuals’ likelihoods of transplant during the study period. This residual disparity may have been the result of SES and cultural factors that we did not control for, such as individual education level, social support, language barriers, transportation resources, or medical mistrust. These factors may complicate individuals’ abilities to remain on the waitlist, such as through medical noncompliance or refusal of a transplant when one becomes available. Future work should evaluate these and other factors included in Ladin, et al.’s conceptual framework for disparities in transplantation 31.

In our sample, there was a significant effect of insurance at ESRD start, an indicator of individual-level SES, suggesting other unmeasured SES factors may play a role. Other variables that may explain some of the racial/ethnic disparity are matching factors, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA), that are unaccounted for in our models even after controlling for blood type and PRA 32,33. HLA is one potential driver of racial/ethnic disparities in transplant 33, leading to gaps in the rate of transplants between whites and racial/ethnic minorities, despite greater willingness by minorities to accept poorer quality (i.e. expanded criteria donor) organs 34.

This study has multiple strengths. This is the first study to examine the causes of hospitalization while waitlisted for kidney transplant and to assess the impact of hospitalization while waitlisted on transplant. We had a large study population, which allowed us to analyze multiple racial/ethnic groups and many covariates. It also allowed us to assess for interaction between race/ethnicity and hospitalization rate concurrently with other covariates. Furthermore, we were able to account for clustering by transplant center and OPO in addition to individual-level variability because of our use of hierarchical mixed models. Lastly, USRDS data have extremely high follow-up rates, making our dataset nearly complete with regard to key exposures and outcomes.

There were some limitations of this study. To assess hospitalization while waitlisted, we had to restrict our study population to individuals with continuous coverage by Medicare parts A and B. This study was observational, and there may be unmeasured variables that created residual confounding. Certain variables, such as neighborhood-level SES indicators and BMI, were only measured once and may have changed over the course of the study, which was not accounted for in analyses. In addition, using area-level SES measures to assess individual-level SES may lead to misclassification bias 35. Finally, we only included individuals who were black, white, or Hispanic due to small sample sizes and heterogeneity in the other groups, and in examining hospitalization rate, we were not able to separate out diverse factors that contribute to hospitalization rate, such as severity of illness and access to preventive care.

This study is the first that we are aware of to examine the impact of hospitalization while waitlisted on kidney transplant and its association with race/ethnicity. We report that hospitalization does not explain the racial/ethnic disparity in kidney transplantation for waitlisted individuals, even after adjusting for individual, transplant center, and OPO-level variables. Further studies are needed to identify modifiable factors associated with racial/ethnic disparities for individuals waiting for kidney transplantation and to test targeted interventions to reduce these inequities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Drs. David Kleinbaum and Joshua Garn for their advice regarding mixed effects models. This work was supported by Bristol Myers Squibb Grant #IM103-326 (R.E.P. and A.B.A.) The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Abbreviations

- ACS

American Community Survey

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- IQR

interquartile range

- OPO

organ procurement organization

- PRA

panel reactive antibody

- SES

socioeconomic status

- USRDS

United States Renal Data System

Footnotes

Authorship: KLN, SAF, MHJ, and REP designed the study. ABA, SAP, and RZ provided subject-area expertise that was essential for the intellectual content of the work. KLN, SAF, and MJH conducted the analysis. All authors provided feedback on the analytic methods and interpretation of results. KLN wrote the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and revised the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lynch RJ, Zhang R, Patzer RE, Larsen CP, Adams AB. Waitlist hospital admissions predict resource utilization and survival after renal transplantation. Annals of surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Schrager JD, et al. The role of race and poverty on steps to kidney transplantation in the Southeastern United States. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2012 Feb;12(2):358–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2012 Feb;12(2):351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, Patzer RE, Kutner NG. Association of race and insurance type with delayed assessment for kidney transplantation among patients initiating dialysis in the United States. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2012 Sep;7(9):1490–1497. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13151211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Volkova N, Kleinbaum D, McClellan WM. Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009 Jun;20(6):1333–1340. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation--clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? The New England journal of medicine. 2000 Nov 23;343(21):1537–1544. 1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432106. preceding 1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sequist TD, Narva AS, Stiles SK, Karp SK, Cass A, Ayanian JZ. Access to renal transplantation among American Indians and Hispanics. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004 Aug;44(2):344–352. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall YN, Choi AI, Xu P, O’Hare AM, Chertow GM. Racial ethnic differences in rates and determinants of deceased donor kidney transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011 Apr;22(4):743–751. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier-Kriesche HU, Port FK, Ojo AO, et al. Effect of waiting time on renal transplant outcome. Kidney international. 2000 Sep;58(3):1311–1317. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feyssa E, Jones-Burton C, Ellison G, Philosophe B, Howell C. Racial/ethnic disparity in kidney transplantation outcomes: influence of donor and recipient characteristics. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2009 Feb;101(2):111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30822-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR. Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. Jama. 1998 Oct 7;280(13):1148–1152. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Nov 25;341(22):1661–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasiske BL, London W, Ellison MD. Race and socioeconomic factors influencing early placement on the kidney transplant waiting list. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 1998 Nov;9(11):2142–2147. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark CR, Hicks LS, Keogh JH, Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ. Promoting access to renal transplantation: the role of social support networks in completing pre-transplant evaluations. Journal of general internal medicine. 2008 Aug;23(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0628-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niewoehner DE. The impact of severe exacerbations on quality of life and the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The American journal of medicine. 2006 Oct;119(10 Suppl 1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds MR, Morais E, Zimetbaum P. Impact of hospitalization on health-related quality of life in atrial fibrillation patients in Canada and the United States: results from an observational registry. American heart journal. 2010 Oct;160(4):752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mapes DL, Lopes AA, Satayathum S, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Kidney international. 2003 Jul;64(1):339–349. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM [computer program] Rockville, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grams ME, McAdams Demarco MA, Kucirka LM, Segev DL. Recipient age and time spent hospitalized in the year before and after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2012 Oct 15;94(7):750–756. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31826205b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moghani Lankarani M, Noorbala MH, Assari S. Causes of re-hospitalization in different post kidney transplantation periods. Annals of transplantation : quarterly of the Polish Transplantation Society. 2009 Oct-Dec;14(4):14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 Apr 2;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Joynt KE. Disparities in surgical 30-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Annals of surgery. 2014 Jun;259(6):1086–1090. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez F, Joynt KE, Lopez L, Saldana F, Jha AK. Readmission rates for Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure and acute myocardial infarction. American heart journal. 2011 Aug;162(2):254–261. e253. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Jama. 2011 Feb 16;305(7):675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAdams-Demarco MA, Grams ME, Hall EC, Coresh J, Segev DL. Early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation: patient and center-level associations. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2012 Dec;12(12):3283–3288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan G, Norris KC, Greene T, et al. Race/ethnicity, age, and risk of hospital admission and length of stay during the first year of maintenance hemodialysis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014 Aug 7;9(8):1402–1409. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12621213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arce CM, Goldstein BA, Mitani AA, Lenihan CR, Winkelmayer WC. Differences in access to kidney transplantation between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites by geographic location in the United States. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013 Dec;8(12):2149–2157. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01560213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis AE, Mehrotra S, McElroy LM, et al. The extent and predictors of waiting time geographic disparity in kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2014 May 27;97(10):1049–1057. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000438623.89310.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashby VB, Kalbfleisch JD, Wolfe RA, Lin MJ, Port FK, Leichtman AB. Geographic variability in access to primary kidney transplantation in the United States, 1996–2005. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2007;7(5 Pt 2):1412–1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathur AK, Ashby VB, Sands RL, Wolfe RA. Geographic variation in end-stage renal disease incidence and access to deceased donor kidney transplantation. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2010 Apr;10(4 Pt 2):1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ladin K, Rodrigue JR, Hanto DW. Framing disparities along the continuum of care from chronic kidney disease to transplantation: barriers and interventions. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009 Apr;9(4):669–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vranic GM, Ma JZ, Keith DS. The Role of Minority Geographic Distribution in Waiting Time for Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2014 Nov;14(11):2526–2534. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall EC, Massie AB, James NT, et al. Effect of Eliminating Priority Points for HLA-B Matching on Racial Disparities in Kidney Transplant Rates. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2011 Nov;58(5):813–816. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohandas R, Casey MJ, Cook RL, Lamb KE, Wen XR, Segal MS. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in the Allocation of Expanded Criteria Donor Kidneys. Clin J Am Soc Nephro. 2013 Dec 6;8(12):2158–2164. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01430213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pardo-Crespo MR, Narla NP, Williams AR, et al. Comparison of individual-level versus area-level socioeconomic measures in assessing health outcomes of children in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2013 Apr;67(4):305–310. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.