Abstract

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory condition that leads to fibrotic plaques, papules and alopecia on the occiput and/or nape of the neck. Traditional medical management focuses on prevention, utilization of oral and topical antibiotics, and intralesional steroids in order to decrease inflammation and secondary infections. Unfortunately, therapy may require months of treatment to achieve incomplete results and recurrences are common. Surgical approach to treatment of lesions is invasive, may require general anesthesia and requires more time to recover. Light and laser therapies offer an alternative treatment for AKN. The present study systematically reviews the currently available literature on the treatment of AKN. While all modalities are discussed, light and laser therapy is emphasized due to its relatively unknown role in clinical management of AKN. The most studied modalities in the literature were the 1064-nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser, 810-nm diode laser, and CO2 laser, which allow for 82–95% improvement in 1–5 sessions. Moreover, side effects were minimal with transient erythema and mild burning being the most common. Overall, further larger-scale randomized head to head control trials are needed to determine optimal treatments.

Keywords: Acne keloidalis nuchae, Hair disorders, Lasers, Systematic review, Therapy, Treatment

Introduction

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory condition that leads to scarring of the hair follicles, development of keloid-like papules and plaques, and scarring alopecia on the nape of the neck and occipital scalp. Studies report the incidence of AKN being between 0.45% and 9%, and occurring mostly in darkerskinned races with curly or kinky hair [1–5]. While this condition most commonly occurs in blacks, AKN can also be seen in Caucasians [29]. Moreover, the condition has a predilection for men, occurring 20 times more frequently than in women [6], and starts after adolescence. The natural course of disease starts with the early formation of inflamed papules with marked erythema. Secondary infection can lead to pustules and abscess formation in some cases. Over time, continued inflammation leads to pronounced fibrosis and keloid formation with coalescence of the papules into large plaques and nodules. Later stages of presentation include chronic scarring and/or scarring alopecia without active inflammation.

While the exact underlying pathogenesis of AKN is not known, the two predominant theories suggest skin injury and the existence of aberrant immune reactions as the underlying causes. Skin injuries from irritation, occlusion, trauma, friction and hair cutting practices have all been implicated as risk factors for the development of AKN [7–10]. The characteristic curvature of afro-textured hair has also been implicated in inciting AKN, but no clinical or pathologic evidence exists to substantiate this [11]. Furthermore, some have proposed that AKN is due to an immune reaction that leads to the cicatricial alopecia. Upon histological examination, a mixed, neutrophilic and lymphocytic infiltration has been observed [36]. In this theory, intrafollicular antigens attract inflammatory cells to the follicle, resulting in damage to the sebaceous gland and follicular wall. This in turn leads to rupture of the follicle and release of antigens into the hair follicle that precipitates the inflammatory process and epithelial destruction leading to fibrosis [12].

Traditional management of the disease focuses on preventing disease progression, including avoidance of mechanical irritation from clothing and use of antimicrobial cleansers to prevent secondary infection [13]. Treatment usually involves use of topical, intralesional or systemic steroids in combination with retinoids and/or antibiotics to decrease inflammation [14, 15]. When the disease progresses from early to late stage, surgical excision and skin grafting may be performed, which require long periods of healing. Recent advances in light and laser therapies offer an alternative treatment option for AKN. However, the potential of these modalities in the treatment for AKN has not been comprehensively reviewed. This review explores medical, surgical and light therapies for AKN and discusses the clinical implications.

Methods

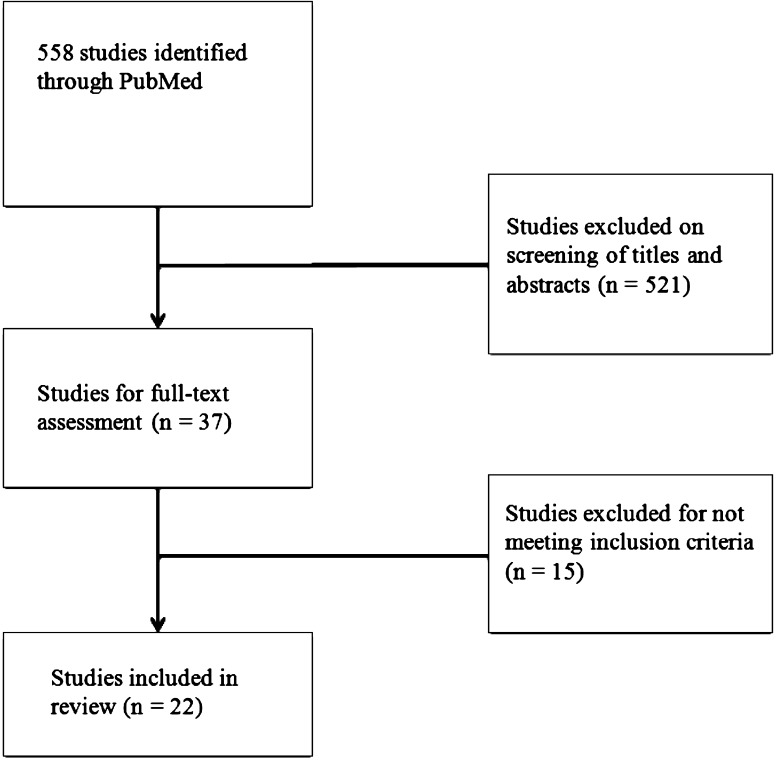

A literature review of the National Library of Medicine database, PubMed, was performed on July 6, 2015 (Fig. 1). The following search terms were used individually: “Acne Keloidalis Nuchae”, “Folliculitis Keloidalis Nuchae”, “Acne Keloidalis” and “Folliculitis Keloidalis”. Search results were cross-checked with the Scopus database using the same search terms. Initial searching returned 558 articles. Only articles written in English were included for further review. The titles and abstracts of the articles were independently reviewed by two authors for relevance to the treatment of AKN. Articles were included if they were original studies and contained suitable background information, clinical presentation, and treatment information for AKN. A total of 22 studies were included, containing 85 total patients treated with different modalities. The majority of studies were case reports/case series. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Fig. 1.

Systematic search of PubMed returned 558 total studies. After review of titles, abstracts, and full-text, 22 studies were included in this review

Results

Conventional Modalities

A total of 15 studies were found utilizing medical and surgical treatments for AKN (see Tables 1, 2). Medical management included the use of topical or oral antibiotics, corticosteroids, retinoids, topical fusidic acid and topical urea. Medical management showed varying degrees of improvement, with complete resolution in one case. Overall, surgical approaches to treating AKN resulted in a drastic improvement of the condition, though there was some recurrence of disease and the cosmetic results were variable. Additionally, there was one report on radiotherapy and dermabrasion.

Table 1.

Medical management of acne keloidalis nuchae

| Study | n | Sex, M:F | Mean age (range) | Previous treatment | Therapy | Specifications | Outcome | Side effects | Mean f/u (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dinehart et al. [7] | 2 | 0:2 | 23, 39 | – | 1. TAC | 1. TAC (10 mg/ml, IJ), ×2 over 2 months | 1. Favorable response. Decrease in size of papules, resolved pruritus, no new lesions at 6 months | – | 6 |

| 2.Tetracycline | 2. Tetracycline (250 mg × 4 per day, ×1 month) | 2. Decreased pain and size of lesions | |||||||

| Harris et al. [24] | 1 | 1:0 | 25 | – | TAC and antibiotics | TAC (IJ) and antibiotics (top./oral) | Little improvement during active football season. Resolved spontaneously off-season | – | – |

| Layton et al. [33] | 11 | 7:4 | 22.9 | Tx naïve | Cryosurgery vs. TAC |

Cryosurgery: 2 × 15 s freeze–thaw cycles, spot freeze technique TAC: 5 mg, IJ |

50% of facial lesions unresponsive to tx. Palpability score correlated with response to tx (P < 0.04). Cryosurgery provided better tx for more vascular lesions (P < 0.03). Overall sustained improvement in keloids | – | 2 |

| Goh et al. [14] | 1a | 1:0 | 27 | Minocycline (PO), doxycycline (PO), mometasone furoate (top.), TAC (IJ) | Isotretinoin | 0.25 mg/kg daily. Then 20 mg every 2–3 days | Vertex of scalp: improved inflammation (in weeks). Neck: less improvement. Follicular tufting/papules: no change. Low dose maintains the vertex | – | – |

| Janjua et al. [25] | 1a | 1:0 | 18 | – | Fusidic acid, cefadroxil, urea | Fusidic acid (top.), cefadroxil (PO, 500 mg bid × 2 weeks), antibiotic (PO), petrolatum and 10% urea (top.) | Marked improvement in inflammation of scalp and neck | – | 6 |

| Millán-Cayetano et al. [35] | 1 | 1:0 | 26 | Cryotherapy, antibiotics (PO/top.), TAC (IJ), isotretinoin (PO), sulphone (PO) | Radiotherapy | 6 MeV linear electron accelerator, 3 Gy × 10 sessions, alternating days | Complete resolution with no recurrence at 20 months | Complete alopecia in irradiated area at 2 months, regained hair at 4 months | 20 |

f/u follow-up, IJ injection, PO per os, TAC triamcinolone, top. topical, Tx treatment

aCase of acne keloidalis nuchae associated with keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans

Table 2.

Surgical management of acne keloidalis nuchae

| Study | n | Sex, M:F | Mean age (range) | Previous treatment | Therapy | Specifications | Outcome | Side effects | Mean f/u (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glenn et al. [4] | 6 | 6:0 | 33.3 (25–40) | Antibiotics (top./PO), steroids (top./IJ), retinoids (top./PO) | Surgical excision | Healing by second intention | Complete wound closure (n = 5, by 3 months). Good to excellent cosmetic results (n = 4). Mild recurrence (n = 2) | Postoperative bleeding (n = 2, resolved with ligature or pressure). Pain | – |

| Pestalardo et al. [31] | 1 | 1:0 | 40 | – | Tissue expansion | Expander (46 days), then local radiotherapy (weekly, total 1000 rad) | No recurrence at 2 years. Good cosmetic result | Infection (at 20 days, tx with cephalexin) | 24 |

| Califano et al. [28] | 5 | – | – | – | Surgical excision | Healing by second intention | Complete wound closure (n = 5, 6–10 weeks). Some hypertrophic scar formation | – | 2-48 |

| Gloster et al. [30] | 25 | 25:0 | 21–45 | Varied medical management | Surgical excision | Layered closure in 1 stage (n = 20), 2-stage excision with layered closure (n = 4), and excision with second-intention healing (n = 1) | Surgical scar usually hidden in new hairline. Patient subjectively rated success of surgery at average of 3.8 (1–4 scale). Small recurrent papules and hypertrophic scars (tx with steroids). No complete recurrence | No postoperative bleeding, infection, dehiscence or excess pain. Hypertrophic scars were excised resulting in moderate wound-edge tension | 12 |

| Bajaj et al. [26] | 2 | 2:0 | 43, 24 |

1. Clindamycin (top.), minocycline (PO) 2. Antibiotics (PO, top.), fluocinolone (top.) |

Surgical excision | Healing by second intention |

1. Granulation evident by 2 weeks, re-epithelialization by 8–10 weeks. Good cosmetic result and no recurrence at 14 months 2. Excellent healing in 3 months, no recurrence at 18 months |

No hypertrophic scarring | 14–18 |

| Verma et al. [32] | 4 | 3:1 | 35, 40, 31, 29 |

1. None 2. TAC (IJ) |

Surgical excision | – | 2. Lesion-free at 9 months | – | – |

| Beckett et al. [27] | 1 | 1:0 | 63 | Various topicals and corticosteroids (IJ) | Surgical excision | Electrosurgery blended mode, 20 W. Healing by second intention | Complete closure with only a small flat scar at 5 weeks. No recurrence at 8 months | – | 8 |

| Etzkorn et al. [29] (2012) | 1 | 1:0 | 44 | Steroids (IJ) | Surgical excision | Healing by second intention | Papules appeared at periphery of excision site at 5 weeks. Tx with doxycycline (100 mg bid ×30 days) and fluocinonide (top.). Complete resolution with patient satisfaction at 7 months | – | 7 |

| D’Souza et al. [34] | 1 | 1:0 | 38 | – | Dermabrasion | ×3 sessions | 50% reduction in size. Referred for surgical excision | – | – |

f/u follow-up, IJ injection, PO per os, TAC triamcinolone, top. topical, Tx treatment

Medical Treatment

The earliest case of medical management of AKN was reported by Dinehart et al. [16] who treated two females with intralesional triamcinolone and tetracycline (oral), respectively. There was marked improvement in both patients. The patient receiving triamcinolone had no new lesions at 6 months, though many small papules remained; the patient receiving tetracycline had dramatic improvement, including a decrease in pain, size and purulence of the lesions. Conversely, Harris et al. [17] reported a case of AKN in a male professional football player. Triamcinolone and antibiotics were administered with little improvement seen until the patient’s offseason, at which time the condition spontaneously resolved. Medical management has also been a suitable therapeutic approach for AKN associated with keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans [14, 18]. Two cases have been reported, both involving young men (aged 18 and 27 years, respectively). Goh et al. [14] utilized oral isotretinoin (20 mg, 0.25 mg/kg/day) after failed attempts with minocycline (oral), doxycycline (oral), mometasone furoate (topical) and triamcinolone acetate (intralesional injection). Within weeks, dramatic improvement was seen in the lesions on the vertex of the patient’s scalp. Inflammation on the neck responded less dramatically, while the patient’s follicular tufting/follicular hyperkeratotic papules exhibited no change. Maintenance on low dose isotretinoin (20 mg every 2–3 days) kept the patients vertex inflammation under control, seen at 1-year follow-up. Janjua et al. [18] used combination topical fusidic acid and oral cefadroxil (500 mg twice daily for 2 weeks) to treat a patient. Antibacterial therapy was repeated as necessary. There was marked improvement in the lesions of the scalp and nuchal area at 6 months, though some hypertrophic scarring and tufts remained. Overall, medical management seemed to improve the condition, though complete resolution was not seen. Thus, the modality may be reserved for mild cases of AKN.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical excision was described in eight studies [4, 19–25]. In one report, six males with AKN refractory to numerous medications, both topical and systemic, underwent surgical excision of the involved areas to muscle fascia or deep subcutaneous tissue [4]. Healing by second intention was allowed, which resulted in an average closure time of 6–8 weeks. Good cosmetic results were achieved in four patients (those receiving horizontal elliptical excision including the posterior hairline), while recurrence occurred in two patients. Another study reported surgical excision and healing by second intention performed on five patients [21]. Although scarring was significant, the cosmetic results were acceptable in all patients. At 2 months to 4 years follow-up, contractures did not limit function nor did disease recur. In two similar studies by Bajaj et al. [19] and Etzkorn et al. [22], a total of three cases of AKN were surgically excised with healing by second intention. Excellent cosmetic results and no recurrences were seen (follow-up at 7, 14 and 18 months, respectively).

Electrosurgery is another treatment option for AKN. This modality allows for excision of the lesion with simultaneous coagulation of small vessels similar to laser excision with CO2. In one case utilizing electrosurgery, healing by second intention resulted in complete closure at 5 weeks with good wound contracture and a small flat scar [20]. No recurrence was observed at 8 months postoperative. In the largest study to date, Gloster et al. [23] performed surgical excision in 25 patients with AKN. Twenty patients underwent excision with layered closure in 1 stage, 4 underwent 2-stage excision with layered closure and one underwent excision with second-intention healing. Treated areas were subjectively scored from poor (1) to excellent (4) by both the patient and physician. At 1-year follow-up, the results were scored with an average overall score of 3.8. Five patients, however, developed hypertrophic scarring and 15 patients had mild recurrences of tiny pustules and papules during the first 4 months that were subsequently treated with topical and intralesional steroids.

An alternative surgical approach was taken in a case of AKN in a 40-year-old male using a semilunar 400-ml tissue expander [24]. Postoperative infiltrations were performed at 14 days and each week thereafter, expanding the tissue by 380 ml. At the 46th post-operative day, the expander was removed and the affected area was closed. Local radiotherapy was administered weekly until 1000 rad was reached. An excellent cosmetic result was achieved, with no recurrence of AKN and no signs of the “stretch-back” phenomenon at 2-year follow-up. The case was complicated by infection at 20 days post-operation that was successfully treated with cephalexin.

A variety of combined treatments have also been reported for the treatment of AKN. Layton et al. [26] compared intralesional triamcinolone with cryosurgery using the spot freeze technique with two 15-s freeze–thaw cycles. Overall, the assigned scores of pre-therapy palpability (used as an indicator of severity) correlated with the response to treatment (P < 0.04) and cryosurgery provided better results for more vascular lesions (P < 0.03). At 8-week follow-up, there were sustained improvements in the lesions. Dermabrasion was attempted in one case of AKN in a 38-year-old male [27]. After three sessions, there was approximately a 50% reduction in lesion size. However, the patient refused additional sessions and was subsequently referred for surgical excision. In one particularly refractory case of AKN reported by Cayetano et al. [28], the patient was treated for 5 years with cycles of cryotherapy, topical antibiotics (clindamycin 1% solution), oral antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg/day), infiltrations of intralesional triamcinolone, oral isotretinoin (50 mg/day) and oral sulphone (100 mg/day). The patient also received electro-curettage and partial excision with primary closure. With continued worsening, the patient underwent radiotherapy at 3 Gy per session for ten sessions on alternating days (total dose of 30 Gy). Complete alopecia was seen at 2 months after radiotherapy which resolved 4 months later, except in the area of the original keloid plaque. The lesion eventually flattened, leading to a small residual scar and good cosmetic results. No recurrence was seen at 20-months follow-up.

Light and Laser Therapy

Lasers utilized included the CO2 laser, 1064-nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser, 59-nm pulse dye laser (PDL), and 810-nm diode laser (Table 3). The earliest study by Kantor et al. used a CO2 laser for surgical excision for late stage treatment of AKN [29]. By using a CO2 laser with a focused beam, fibrotic areas in six black patients and two white patients could be removed in an outpatient-based setting with local anesthesia. Moreover, none of the patients who were treated using this modalityhad a relapse. Two patients in the study with early AKN were treated with laser evaporation using the unfocused beam setting with 130–150 J/cm2 fluence with three to four passes in one session. However, relapse occurred in both cases. In another case, CO2 laser evaporation with the same fluence setting was utilized in a Caucasian male who had developed AKN while on chronic cyclosporine treatment for a heart transplant. The patient’s AKN relapsed shortly after treatment forcing the patient to undergo surgical intervention [30]. In a third case involving a Caucasian male, CO2 laser excision was coupled with a single postoperative intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetate (5 ml of 25 mg/ml) and three radiotherapy sessions of 400 cGY [31]. The first of which was given on the same day following the procedure. The patient developed a few satellite lesions that were treated with CO2 laser excision. The patient had a full recovery and regrowth of hair in the treated region.

Table 3.

Light and laser treatments for acne keloidalis nuchae

| Study | n a | Mean age (range) | Therapy | Specifications | Fluence (J/cm2) | Spot Size | Outcomes | Side effects | Mean f/u (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okoye et al. [21] | 11 | 36.6 (25–45) | UVB Metal halide arc lamp 290–320 nm (peak 303 and 313 nm) |

Split-scalp design 3×/week for 16 weeks on treatment side 3×/week for 8 weeks on control side |

Minimal erythema dose 0.23–0.48 Increase 20% per wk for 1st 8 weeks Cumulative dose 29.7 at 8 weeks, 82.2 at 16 weeks |

– |

Moderate to marked improvement 34% reduction at 8 weeks 49% reduction at 16 weeks |

Transient mild burning and erythema | 2 |

| Dragoni et al. [19] | 1 | 23 | 595 nm PDL | PDL; 0.5 ms pulse | 6.5 | 10 mm | PDL; transient improvement with lesions recurring after 1 month | None reported | 6 |

| 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser |

Nd:YAG; 2 pulses (5 and 18 ms) 4 sessions, 1 month apart |

110–120 | 4 mm | Nd:YAG; Improvement in scarring and clinical picture | |||||

| Esmat et al. [20] | 16 | 31.88 (22–54) | 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser |

5 sessions 1 month apart Pulse duration 10–30 ms |

35–45 | – |

Significant improvement 3 treatments 82% mean improvement after 5th session Early lesions marked (>75%) improvement Late lesions moderate to marked improvement (>51%) |

Transient crusting Decreased hair density in treated area |

12 |

| Shah [18] | 2 | 36, 50 | 810 nm diode laser | 4 sessions at 4–6 weeks apart |

Sessions 1 and 2 fluence 23, pulse 100 ms Sessions 3 and 4 fluence 26, pulse 100 ms |

_ | 90–95% clearance of lesions | Transient mild burn in one patient | 6 |

| Azurdia et al. [17] | 1 | 30 | 10,600 nm CO2 laser | 1 session of laser evaporation | 150 | – | Failure to respond referred for surgical intervention | – | 1 |

| Kantor et al. [16] | 8 | 31 (19-40) | 10,600 nm CO2 laser | 1 session of laser excision or evaporation | Excision 64,000 W/cm2 | 0.2 mm |

No recurrence with laser excision, no general anesthesia needed Laser vaporization little benefit with recurrence |

Minimal postoperative pain | 3–47 (avg. 14.8) |

| Vaporization 130–150 W/cm2, 3–4 passes | 2 mm | ||||||||

| Sattler et al. [31] | 1 | 38 | 10,600 nm CO2 Laser |

1 session of laser excision Intralesional triamcinolone acetate 3 session of 400 cGY of radiation |

Excision 64,000 W/cm2 | – | No recurrence with combination therapy, regrowth of hair | _ | _ |

Avg average, cGY centigray, FP Fitzpatrick skin type, Nd:YAG neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet, PDL pulse dye laser, y/o years old

aAll patients receiving light and laser therapies were male

In a case series by Shah [32], 2 males were treated using a 810-nm diode laser who had previous treatment failures with oral antibiotics, intralesional and topical steroids. After 4 treatment sessions of 23–26 J/cm2 fluence with 100 ms pulses, the patients had a 90% and 95% clearance, respectively, that was maintained at 6-months follow-up. Treatments were tolerated with only transient mild burning.

Dragoni et al. [33] treated a single fair-skinned 23-year-old Caucasian male using a 595-nm PDL with 6.5 J/cm2 fluence and 0.5 ms pulse. The results, however, were transient and lesions returned in 1 month. Subsequently, a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with 101–120 J/cm2 fluence was used for four sessions, which lead to a significant improvement in scarring that was clinically apparent. Esmat et al. [34] also used a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser to treat patients with AKN in a pilot study using 35–45 J/cm2 fluence over five sessions. Patients between the ages of 22 and 54 years old with Fitzpatrick skin types 3 and 4 were treated. Significant improvements were seen after the third treatment and in 82% of the lesions after the 5th session. Moreover, biopsies taken from the treated area showed significant reductions in the inflammatory infiltrate after the final treatment. No recurrences of lesions were noted at 1-year follow-up.

Light therapy consisted of the use of a 290- to 320-nm targeted UVB (tUVB) halide arc lamp (Table 3). The most recent study by Okoye et al. [35] used tUVB light to treat 11 male patients using a split-scalp designed study. Initial UVB dosage was determined using the minimal erythema dose that ranged between 0.23 and 0.48 J/cm2. Treatment dosing was increased by 20% per week until the end of 8 weeks and was maintained at the same dose for an additional 8 weeks. The control side of the scalp was treated after the 8th week according to the same protocol until the end of the study at 16 weeks. Treatments were tolerated well with only mild burning and erythema. Patients were given two to three treatments per week. A significant improvement was noted on the treated side by 34% at 8 weeks and 49% at 16 weeks. The results were maintained at 2-months follow-up. In addition to clinical improvements, an up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinases MMP1, MMP9, TGFB1 and COL1A1 were seen by histology, indicating higher rates of extracellular matrix turnover.

Discussion

AKN is a common condition, which can lead to significant scarring, alopecia and negatively impact on quality of life. The pathogenesis of AKN is not completely understood, though trauma and/or immune reactions are thought to play a role. Other factors in disease progression have been suggested, such as a familial component or a cutaneous manifestation of metabolic syndrome [25, 27]. However, further investigation to elucidate the underlying pathogenesis is required.

To date, a number of treatments have been used to treat this condition, from topical antibiotics to surgical excision of fibrotic lesions. Traditional medical management can require months of daily treatment and may relapse after discontinuation of treatment [6]. Light and laser treatments can offer an alternative to medical management that is noninvasive and generally well tolerated. CO2 laser excision can be used as monotherapy in place of surgical excision of AKN lesions without the need for general anesthesia or in combination with intralesional steroids and radiotherapy. However, CO2 vaporization is not very effective in treating AKN because lesions recur shortly after treatment and because of the incidence of scarring in dark-skinned individuals following CO2 vaporization.

Medical management includes intralesional injection and/or topical corticosteroids, topical or oral antibiotics (particularly tetracyclines), and retinoids. Oral isotretinoin (20 mg, 0.25 mg/kg/day) was shown to improve inflammation, but had minimal effect on follicular tufting/follicular hyperkeratotic papules. Amongst the medical modalities, patients receiving intralesional steroids had the most dramatic improvement.

Surgical excision, while extensively discussed in the literature, should be reserved for more extensive and refractory lesions. Healing by second-intention was the most common method used postoperatively. Cryosurgery provided a varied response to lesions, though may be best suited for more vascular lesions [26]. Surgical or cryosurgical treatment with secondary intention healing is the most effective treatment modality for AKN; however, the outcomes are still not optimal. Of the 41 patients treated by surgical excision that were included in this review, 17 had mild recurrence. Additionally, scarring is the major concern with a surgical approach, though use of a horizontal ellipse encompassing the posterior hairline resulted in good to excellent cosmesis by allowing the surgical scar to be hidden in the newly formed hairline. Dermabrasion was reported in one case and did not achieve complete resolution. Radiotherapy was used in two cases of AKN that were refractory to extensive and aggressive treatment [28, 31]. While this modality resulted in complete resolution with no recurrence; radiotherapy should be reserved for the most severe and refractory cases, considering the side effects of such treatment.

The two most extensively studied light and laser therapies include treatment with a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and tUVB light. Among the light and laser modalities, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser and 810-nm diode laser appears to be the most effective for treating AKN. Results from these small studies are promising with therapeutic responses in the range of 82–95%. While tUVB therapy was well tolerated with only mild burning and erythema, it was not as effective as the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, with clinical improvements in the range of 34–49%.

Overall, laser and light therapies for AKN appear to work by decreasing the inflammatory response and/or destroying the hair follicle, which appears to be a nidus that prolongs the vicious cycle of inflammation and fibrosis seen with AKN. Moreover, in the case of tUVB therapy, there is a modulation in expression of matrix metalloproteinases, suggesting that extracellular matrix turnover is enhanced which may act to improve lesions [35].

Conclusions

Medical management of AKN can be used in mild cases. Surgical excision should be reserved for more extensive lesions with prominent fibrosis. However, concern for post-surgical scarring must be considered. Overall, management of AKN with light and laser treatments looks promising with 1064-nm Nd:YAG, 810-nm Diode, and CO2 lasers that allow for 82–95% improvement in 1–5 sessions. Moreover, side effects were minimal with transient erythema and mild burning being the most common. However, the studies are primarily based on case series and small pilot studies. Thus, larger-scaled randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up are needed to effectively assess these treatments.

Acknowledgments

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Eric L. Maranda, Brian J. Simmons, Austin H. Nguyen, Victoria M. Lim, and Jonette E. Keri have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies on human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/E1E4F060549DE1A0.

References

- 1.Adegbidi H, Atadokpede F, do Ango-Padonou F, Yedomon H. Keloid acne of the neck: epidemiological studies over 10 years. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(Suppl 1):49–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunwell P, Rose A. Study of the skin disease spectrum occurring in an Afro-Caribbean population. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(4):287–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George AO, Akanji AO, Nduka EU, Olasode JB, Odusan O. Clinical, biochemical and morphologic features of acne keloidalis in a black population. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32(10):714–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenn MJ, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 Pt 1):243–246. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salami T, Omeife H, Samuel S. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in Nigerians. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(5):482–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21(4):645–653. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8635(03)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinehart SM, Herzberg AJ, Kerns BJ, Pollack SV. Acne keloidalis: a review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15(6):642–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1989.tb03603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halder RM. Hair and scalp disorders in blacks. Cutis. 1983;32(4):378–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenney JAJ. Dermatoses: common in blacks. Postgrad Med. 1977;61(6):122–127. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1977.11712223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JD, Odom RB. Pseudofolliculitis capitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113(3):328–329. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1977.01640030074012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, Pollack SV. Acne keloidalis. Transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12(2):109–121. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199004000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperling LC, Homoky C, Pratt L, Sau P. Acne keloidalis is a form of primary scarring alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(4):479–484. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(2):183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goh MSY, Magee J, Chong AH. Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans and acne keloidalis nuchae. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46(4):257–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stieler W, Senff H, Janner M. Folliculitis nuchae scleroticans–successful treatment with 13-cis-retinoic acid (isotretinoin) Hautarzt. 1988;39(11):739–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinehart SM, Tanner L, Mallory SB, Herzberg AJ. Acne keloidalis in women. Cutis. 1989;44(3):250–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris H. Acne keloidalis aggravated by football helmets. Cutis. 1992;50(2):154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janjua SA, Iftikhar N, Pastar Z, Hosler GA. Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans associated with acne keloidalis nuchae and tufted hair folliculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(2):137–140. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bajaj V, Langtry JAA. Surgical excision of acne keloidalis nuchae with secondary intention healing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(1):53–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckett N, Lawson C, Cohen G. Electrosurgical excision of acne keloidalis nuchae with secondary intention healing. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(1):36–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Califano J, Miller S, Frodel J. Treatment of occipital acne keloidalis by excision followed by secondary intention healing. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 1999;1(4):308–311. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.1.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etzkorn JR, Chitwood K, Cohen G. Tumor stage acne keloidalis nuchae treated with surgical excision and secondary intention healing. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(4):540–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gloster HMJ. The surgical management of extensive cases of acne keloidalis nuchae. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(11):1376–1379. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.11.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pestalardo CM, Cordero AJ, Ansorena JM, Bestue M, Martinho A. Acne keloidalis nuchae. Tissue expansion treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(8):723–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma SB, Wollina U. Acne keloidalis nuchae: another cutaneous symptom of metabolic syndrome, truncal obesity, and impending/overt diabetes mellitus? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11(6):433–436. doi: 10.2165/11537000-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Layton AM, Yip J, Cunliffe WJ. A comparison of intralesional triamcinolone and cryosurgery in the treatment of acne keloids. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(4):498–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb03385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Souza P, Iyer VK, Ramam M. Familial acne keloidalis. Acta dermato-venereologica Norway. 1998;78(5):382. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Millan-Cayetano JF, Repiso-Jimenez JB, Del Boz J, de Troya-Martin M. Refractory acne keloidalis nuchae treated with radiotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2015. doi:10.1111/ajd.12380. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 Pt 1):263–267. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azurdia RM, Graham RM, Weismann K, Guerin DM, Parslew R. Acne keloidalis in caucasian patients on cyclosporin following organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol Engl. 2000;143(2):465–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sattler ME. Folliculitis keloidis nuchae. WMJ. 2001;100(1):37–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah GK. Efficacy of diode laser for treating acne keloidalis nuchae. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71(1):31–34. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.13783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dragoni F, Bassi A, Cannarozzo G, Bonan P, Moretti S, Campolmi P. Successful treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae resistant to conventional therapy with 1064-nm ND:YAG laser. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013. p. 231–232. [PubMed]

- 34.Esmat SM, Hay RMA, Zeid OMA, Hosni HN. The efficacy of laser-assisted hair removal in the treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae; a pilot study. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(5):645–650. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okoye GA, Rainer BM, Leung SG, Suh HS, Kim JH, Nelson AM, et al. Improving acne keloidalis nuchae with targeted ultraviolet B treatment: a prospective, randomized, split-scalp comparison study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(5):1156–1163. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernárdez C, Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Histologic features of alopecias: part II: scarring alopecias. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(4):260–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]