History

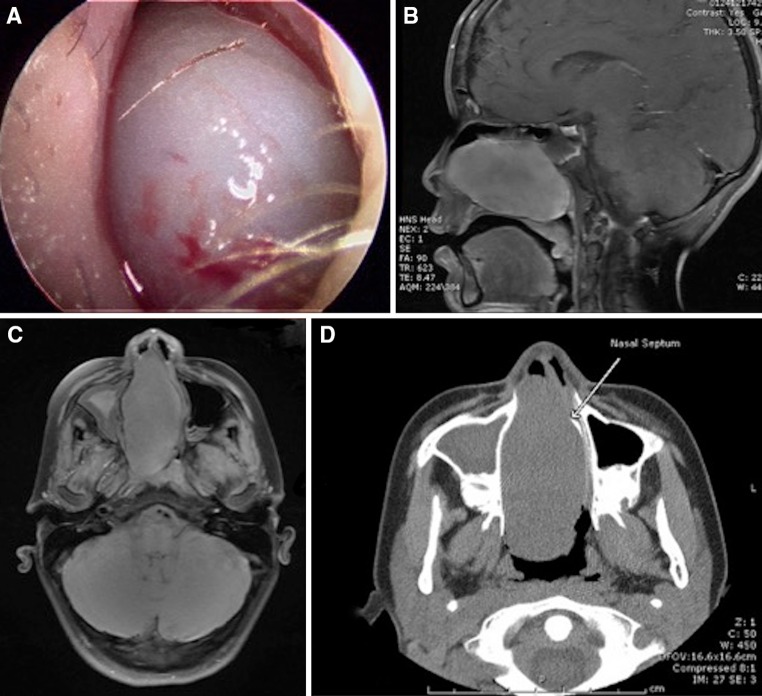

A 12 year old male presented with an 18-month history of intermittent epistaxis. Clinical examination revealed a firm gray white mass that obstructed the right nares (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Nasal endoscopy shows a gray polypoid tumor filling the right nares. b Sagittal T1 contrast enhanced image demonstrates relatively homogenous enhancement of the nasal cavity mass extending into the nasopharynx. Mucosal thickening and fluid within the right sphenoid sinus is noted. c Axial T1 fat-saturated image demonstrates a large mass within the nasal cavity that abuts the medial wall of the left maxillary sinus and causes leftward deviation of the nasal septum. Mucosal thickening and opacification of the right maxillary sinus is seen. d Axial CT image shows a large mass within the nasal cavity that extends to the nasopharynx and shows leftward deviation of the nasal septum

Radiologic Features

Magnetic resonance imaging (MR) of the sinuses revealed a well-circumscribed mass with homogenous enhancement in the right nasal cavity, which measured 4.2 cm craniocaudal by 7.2 cm anterior–posterior by 3.2 cm transverse and extended into the nasopharynx. After administration of Magnevist intravenous contrast, small foci of low signal were seen suggesting early necrosis within the central aspect of the lesion. Other features that might suggest an aggressive lesion, including destructive bony changes or periosteal reaction, were not identified. The sagittal T1 contrast enhanced images demonstrate relatively homogenous enhancement of the nasal cavity mass showing extension into the nasopharynx. Mucosal thickening and fluid within the right sphenoid sinus is also present (Fig. 1b). The axial T1 fat-saturated image demonstrates a large nasal cavity mass that abuts the medial wall of the left maxillary sinus and causes leftward deviation of the nasal septum. Mucosal thickening and opacification of the right maxillary sinus is seen (Fig. 1c). The mass was hypointense on T1-weighted image and hyperintense on T2-weighted image. A coronal computed tomography (CT) image also demonstrated the large nasal cavity mass as leading to leftward deviation of the nasal septum, which now abuts the medial wall of the left maxillary sinus (Fig. 1d).

Diagnosis

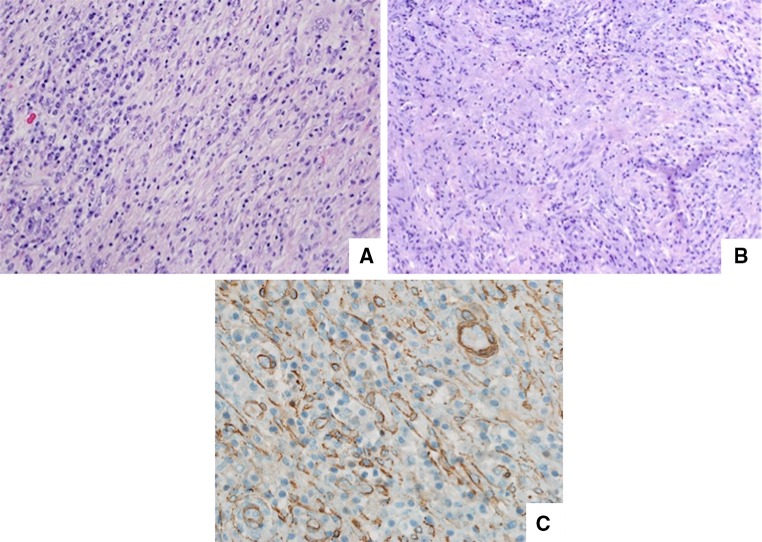

The gross tissue specimen consisted of multiple large, tan-white, vaguely polypoid soft tissue masses which, upon sectioning, revealed a dull tan-white homogenous cut surface. The hematoxylin and eosin stained slides revealed a variably cellular proliferation characterized by large, bland spindled and ovoid cells arranged in fascicular, haphazard and storiform patterns (Fig. 2a, b) that, along the periphery imparted an infiltrative growth pattern. Vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli were a notable feature, although a high mitotic rate was not. These large cells were set within a myxoid background containing abundant vasculature along with a loosely scattered proliferation of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Numerous Dutcher bodies, Russell bodies, and Mott cells (cytoplasmic immunoglobulin inclusions) were included. The spindled cells showed reactivity for SMA (Fig. 2c), CD68 and D2-40, but were negative for ALK1, pan-cytokeratin, CD34, desmin, and S100. Ki-67 revealed a proliferation index of less than 5 %. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for ALK gene rearrangements was negative. The combined histologic features and immunophenotype were most consistent with inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

Fig. 2.

a Low magnification shows a bland spindle cell neoplasm arranged in a fascicular pattern with a predominantly lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. b Cytologically bland cells arranged in a storiform pattern within a myxoid background. c Smooth muscle actin highlights myofibroblasts and vascular structures

Discussion

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, previously termed inflammatory pseudotumor as well as plasma cell granuloma, is a lesion composed of spindled myofibroblasts with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils [1]. It primarily occurs in childhood and demonstrates a propensity for the lungs [2]. Of the extrapulmonary sites, mesentery and omentum are the most commonly reported, while head and neck sites are the least common [3]. Of the head and neck sites, larynx is the most common [4].

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging studies are non-specific for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor occurring in the maxillary sinuses. On MR, the lesion typically presents with intermediate signal intensity, while CT shows mild enhancement of the soft tissue lesion [5]. Both imaging studies demonstrate an aggressive lesion which erodes bone locally and extends into the nasal fossa, features which can mimic a malignant tumor [5]. Destruction of at least one sinus wall is a common finding [6], and extension into the orbital walls has been reported [6–8]. The differential diagnosis would therefore include primary or metastatic soft tissue malignant neoplasms and destructive fungal infections, however, less aggressive lesions may give the impression of an inflammatory sinonasal polyp or sinonasal papilloma.

Clinically, patients may present with nasal obstruction, facial pain, headache, toothache, eye pain, epistaxis, and facial swelling [6]. Pulp necrosis in maxillary teeth adjacent to the lesion has been reported [9]. Grossly, sinonasal IMTs are rubbery to firm and variably red, gray and/or yellow and the cut surface is gray white and homogenous. Coffin and colleagues [3] identified 3 primary histologic patterns in extrapulmonary IMTs which have also been seen in sinonasal IMTs by He and colleagues [6] and are as follows: (a) loosely arrayed stellate and plump spindle cells in a myxoid background with an inflammatory cell infiltrate, (b) a compacted spindle cell proliferation with dense collagen deposition, and (c) a hypocellular pattern with scar-like collagen. The inflammatory infiltrate is composed primarily of a polyclonal population of plasma cells [10] with variable numbers of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, although in some tumors the eosinophil is the predominant inflammatory cell [3]. Lesions with similar histologic features would include nodular fasciitis, (myo)fibromatosis, low grade myofibroblastic sarcoma, and fibrous histiocytoma [6, 10]. In addition, IgG4 related inflammatory pseudotumors share many morphologic features with IMT but typically demonstrate anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) negativity and a high expression of IgG4 in plasma cells [11, 12].

By immunohistochemistry, IMTs are strongly and diffusely positive for vimentin and show variably focal-to-diffuse patterns of reactivity for smooth muscle actin [1, 3, 6]. Muscle specific actin and desmin are also commonly seen, while focal cytokeratin positivity occurs in approximately 30 % of cases [1, 3]. ALK positivity is seen in approximately 50 % of all IMT cases [1, 13] and correlates with the presence of ALK gene (chromosome 2p23) [13] rearrangements identified via FISH. In IMTs of the sinonasal tract, rare (0–4 %) cases are reactive for ALK [6, 14].

The etiology of IMT is not completely understood. It has been suggested that Epstein Barr Virus (EBV), Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), and ALK rearrangements are implicated in IMTs, and that ALK-positive IMTs should be considered as separate entities from those associated with EBV or HHV-8 [15, 16]. Arber and colleagues [17] documented 7 of 17 cases (42 %) positive for EBV by in situ hybridization (EBER ISH) and proposed IMTs may either represent reactive proliferations to EBV infection or true clonal neoplasms. Gómez-Román et al. [18] identified 5 cases of pulmonary IMT, which demonstrated mRNA specific to HHV-8 via reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In this series, the four cases with available tissue were shown to be negative for ALK by immunostaining [18]. In a series of 16 pediatric IMTs, Mergan and colleagues [15] failed to identify any cases positive for HHV-8 via immunohistochemistry, however two cases were positive for EBV by EBER ISH. At this time there is no documentation of HHV-8, EBV, or IgG4-related disease in sinonasal IMTs [6].

Treatment involves a combination of surgical excision, radiotherapy and/or corticosteroids [6, 8, 19, 20]. Lateral rhinotomy [21] and Caldwell Luc procedure [22] have been successfully utilized. In one report, a patient with a very large IMT encompassing the entire left maxillary antrum, nasal cavity, orbit and the oral cavity, underwent a hemi-maxillectomy via a Weber–Fergusson approach with no recurrence [7].

Although IMTs may demonstrate an aggressive appearance and extensive growth patterns on imaging studies, early detection, assured excision with appropriate adjuvant therapy and regular follow-up typically increase disease-free outcomes. The current patient underwent complete excision and has experienced an uneventful follow-up period to date.

Footnotes

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. I certify that all individuals who qualify as authors have been listed; each has participated in the conception and design of this work, the writing of the document, and the approval of the submission of this version; that the document represents valid work; that if we used information derived from another source, we obtained all necessary approvals to use it and made appropriate acknowledgements in the document; and that each takes public responsibility for it. We are military service members. This work was prepared as part of our official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

References

- 1.Coffin CM, Fletcher JA. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. pp. 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miettinen M. Modern soft tissue pathology: tumors and non-neoplastic conditions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor) A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859–872. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson L, Wenig B. Diagnostic pathology: head and neck. Salt Lake City: Amirsys; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Som PM, Brandwein MS, Maldjian C, Reino AJ, Lawson W. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the maxillary sinus: CT and MR findings in six cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:689–692. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.3.8079869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He CY, Dong GH, Yang DM, Liu HG. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinus: a clinicopathologic study of 25 cases and review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272:789–797. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazaridou M, Dimitrakopoulos I, Tilaveridis I, Iordanidis F, Kontos K. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the maxillary sinus and the oral cavity. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;18:111–114. doi: 10.1007/s10006-013-0409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ushio M, Takeuchi N, Kikuchi S, Kaga K. Inflammatory pseudotumour of the paranasal sinuses—a case report. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:533–536. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SY, Yang SE. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the maxillary sinus related with pulp necrosis of maxillary teeth: case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:684–687. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maruya S, Kurotaki H, Hashimoto T, Ohta S, Shinkawa H, Yagihashi S. Inflammatory pseudotumour (plasma cell granuloma) arising in the maxillary sinus. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:322–327. doi: 10.1080/00016480410022994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhagat P, Bal A, Das A, Singh N, Singh H. Pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor and IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Virchows Arch. 2013;463:743–747. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato Y, Kojima M, Takata K, Huang X, Hayashi E, Manabe A, Miki Y, Yoshino T. Immunoglobulin G4-related lymphadenopathy with inflammatory pseudotumor-like features. Med Mol Morphol. 2011;44:179–182. doi: 10.1007/s00795-010-0525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:509–520. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213393.57322.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu ZJ, Zhou SH, Yan SX, Yao HT. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase expression and prognosis in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours of the maxillary sinus. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:2000–2008. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mergan F, Jaubert F, Sauvat F, Hartmann O, Lortat-Jacob S, Révillon Y, Nihoul-Fékété C, Sarnacki S. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in children: clinical review with anaplastic lymphoma kinase, Epstein-Barr virus, and human herpesvirus 8 detection analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1581–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto H, Kohashi K, Oda Y, Tamiya S, Takahashi Y, Kinoshita Y, Ishizawa S, Kubota M, Tsuneyoshi M. Absence of human herpesvirus-8 and Epstein-Barr virus in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with anaplastic large cell lymphoma kinase fusion gene. Pathol Int. 2006;56:584–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arber DA, Kamel OW, van de Rijn M, Davis RE, Medeiros LJ, Jaffe ES, Weiss LM. Frequent presence of the Epstein-Barr virus in inflammatory pseudotumor. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:1093–1098. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gómez-Román JJ, Sánchez-Velasco P, Ocejo-Vinyals G, Hernández-Nieto E, Leyva-Cobián F, Val-Bernal JF. Human herpesvirus-8 genes are expressed in pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor) Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:624–629. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newlin HE, Werning JW, Mendenhall WM. Plasma cell granuloma of the maxillary sinus: a case report and literature review. Head Neck. 2005;27:722–728. doi: 10.1002/hed.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soysal V, Yigitbasi OG, Kontas O, Kahya HA, Guney E. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the nasal cavity: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;61:161–165. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(01)00561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang WH, Dai YC. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the nasal cavity. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chuang CC, Lin HC, Huang CW. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the sinonasal tract. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:165–168. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]