Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) in athletic patients.

Materials and Methods

From July 2003 to May 2013, 388 patients (422 hips) who underwent arthroscopic surgery for FAI were evaluated demographic characteristics. The patients' age, gender, diagnosis, and type of sports were analyzed using medical records and radiography.

Results

Among 422 hips in 388 patients, 156 hips were involved with sports. Among the 156 hips, 86, 43, and 27 hips were categorized as cam, pincer, and mixed type, respectively. Types of sports were soccer, baseball and taekwondo which showed 44, 36 and 35 hips, respectively. Also, cases related to sports according to age were 63 hips for twenties and 12 hips for teenagers in which the two showed highest association to FAI. The kinds of sports that showed high association were 28 hips of soccer and 20 cases of martial arts such as taekwondo and judo for twenties and 9 hips of martial arts for teenagers which was the highest.

Conclusion

FAI usually occurs in young adults and is highly related to sports activity. Most of the FAI type related to sports activity was cam type, and soccer and martial arts such as taekwondo were the most common cause of it.

Keywords: Hip, Femoroacetabular impingement, Prevalence, Sports, Arthroscopy

INTRODUCTION

Many studies have been reported that femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) can be the cause of cartilage or acetabular labral lesion ultimately resulting in degenerative arthritis1,2,3). Two types of FAI have been described: cam and pincer. In cam-type impingement, the abnormally shaped femoral head-neck junction abuts the anterosuperior acetabulum1). In pincer-type impingement, the deep or cranially retroverted acetabulum provides excessive coverage to the femoral head and thereby restricts movement1). The two types are commonly combined1).

The advancement in the diagnostic methods and hip arthroscopy has allowed FAI that are caused by sports injuries to be diagnosed at an increasing rate and this has promoted discussion concerning the treatment. The prevalence of FAI as a clinical diagnosis is estimated to be 10-15% in a general adult population2). Particularly, athletes have been more often associated with FAI than ordinary patients4,5,6,7).

There have been studies introducing cases showing high correlation of martial arts movements including kicks with FAI8,9). Also, there was study which reported prevalence of FAI in Asian patients with osteoarthritis of the hip10). However, to the best of our knowledge, there has not been any official paper evaluating the relationship between sports activity and the prevalence of FAI. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of symptomatic FAI in athletic patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patient Selection

From July 2003 to May 2013, 388 patients (422 hips) who underwent arthroscopic surgery for FAI were evaluated demographic characteristics. The patients who complained of hip pain underwent history taking, physical examinations including anterior impingement test11) and Patrick test12), and simple radiography (the pelvis anteroposterior view, the frog-leg lateral view, the false profile view and cross-table lateral view) at the time of the visit (Fig. 1). Three-dimensional computed tomographic scan (3D CT) was taken preoperatively in patient who was scheduled to undergo arthroscopic surgery for identifying the precise site of the bump and osteophyte and postoperatively for checking state of femoro-and/or acetabuloplasty (Fig. 2). We included patients associated sports as we defined who underwent arthroscopic surgery due to FAI (cam, pincer, or mixed type). We excluded patients with the following: (1) patients with insufficient radiographs or records; (2) history of high-energy hip trauma (i.e., fracture or dislocation); (3) history of surgery involving the femur or pelvis; (4) Tönnis Grade 2 or above13); (5) idiopathic inflammatory arthritis (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis or seronegative spondyloarthropathy); (6) proliferative disease of the hip (i.e., synovial chondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis); (7) Legg-Calvé-Perthes deformity; or (8) developmental dysplasia of the hip.

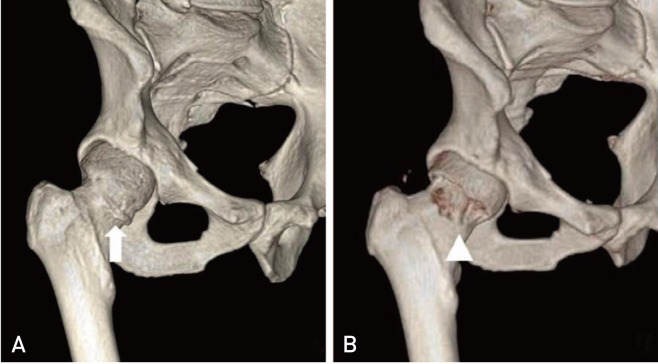

Fig. 1. A plain hip radiograph of a 35-year-old male with chronic right hip pain, who was a master of taekwondo, shows decreased femoral offset and femoral flattening (arrow).

Fig. 2. Three-dimensional computed tomographic (3D CT) scan images. (A) Preoperative 3D CT image shows spur on femoral head neck junction (arrow). (B) Postoperative 3D CT image shows state underwent arthroscopic femoroplasty (arrowhead).

In this study, the athletic patient was defined as one who participated in sports or exercise more than 2 hours a day and 3 days per week for more than 1 year until hip pain developed. And alpha angle was considered to have been increased if more than 50° and anterior femur offset was considered to have been decreased if less than 8 mm and these were classified as cam type14,15). Acetabular retroversion is a hip dysplasia in which the alignment of the acetabulum does not face the normal anterolateral direction, but inclined more posterolaterally16). In the simple radiography, crossover of the anterior wall of acetabulum over the posterior wall (focal cross over sign, figure of 8 sign) was defined as acetabular retroversion, and the adjoining of acetabular fossa and ilioischial line to be coxa profunda and the femur head passing the ilioischial as acetabular protrusio17). These were classified as the pincer type. Cam types and pincer types were classified under such radiological standards and coexistence of both as mixed types18). 3D CT was taken for geography of bump on femur and alpha angle measurement. Under suspicion of labral tear or soft tissue lesion such as injury of hip joint cartilage or ligamentum teres, magnetic resonance image was taken.

2. Surgical Technique and Postoperative Care

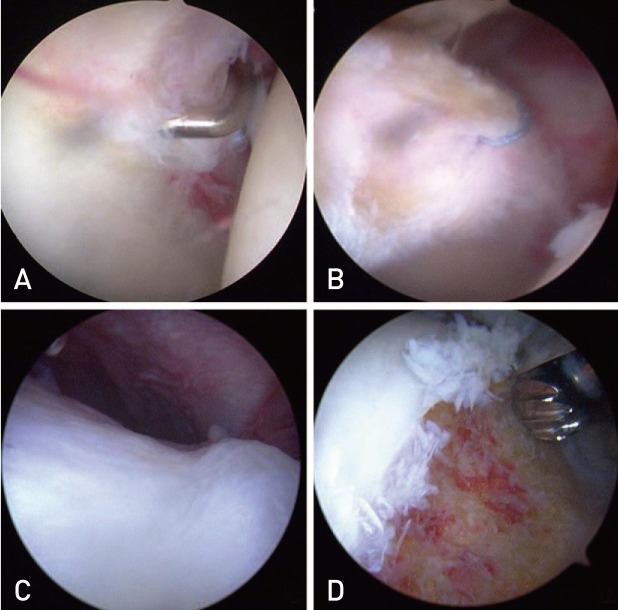

All arthroscopic procedures were performed by a single senior surgeon. The intra-articular pathologies were identified after appropriate anterolateral capsulotomy, loose fragments were removed using a grasper via the anterior or posterolateral portal, and labral tears were debrided using an arthroscopic shaver or repaired using a 2.9 mm BIORAPTOR suture anchor (Smith & Nephew, London, UK) (Fig. 3). Pathologies of the peripheral compartment, such as a femoral head neck bump or bony spur, were treated by femoroplasty (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Arthroscopic view images. (A) Arthroscopic view shows partial labral tear. (B) It shows the repair of labral tear. (C) It shows bump on femoral head-neck junction. (D) It shows state underwent arthroscopic femoroplasty.

All cases underwent 3D CT on the second day postoperatively to check the postoperative state of the acetaulo- and femoroplasty and removal of loose bodies. All patients were discharged on the third day after the procedure.

3. Analysis of Epidemiology and Research Approval

The patients' age, gender, diagnosis, and type of sports were analyzed using medical records and radiography. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution and informed consent was waived from all patients.

RESULTS

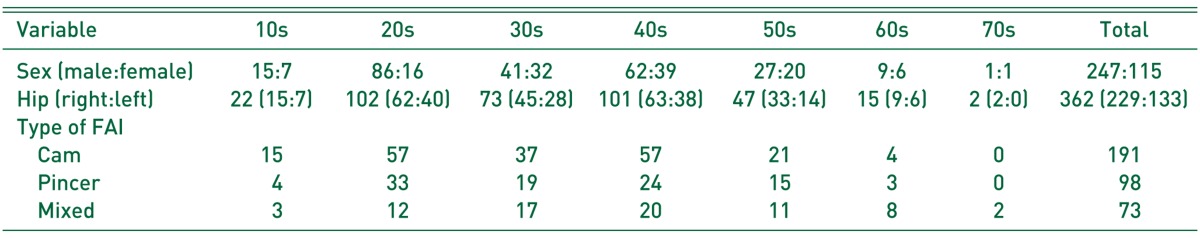

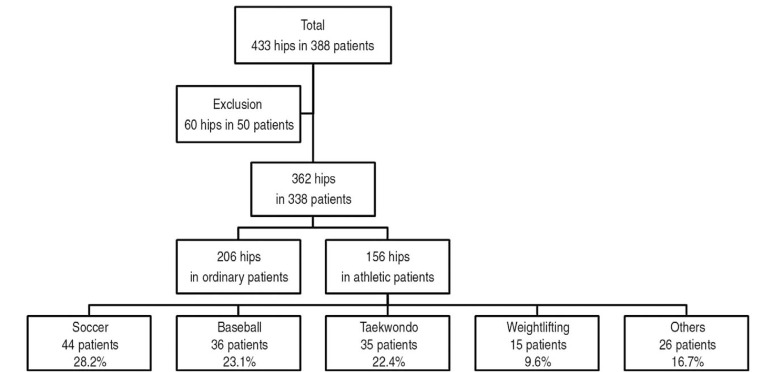

Among 422 hips in 388 patients, 60 hips in 50 patients were excluded because 5 hips with insufficient radiographs or records, 12 hips with history of high-energy hip trauma, 5 hips with history of surgery involving the femur or pelvis, 5 hips with Tönnis Grade 2 or above, 18 hips with idiopathic inflammatory arthritis, 10 hips with proliferative disease of the hip, 3 hips with Legg-Calvé-Perthes deformity, 2 hips with developmental dysplasia of the hip. The remaining study population consisted of 362 hips in 338 consecutive patients (229 male and 109 female). Epidemiology of patients with FAI according to ages was shown on Table 1.

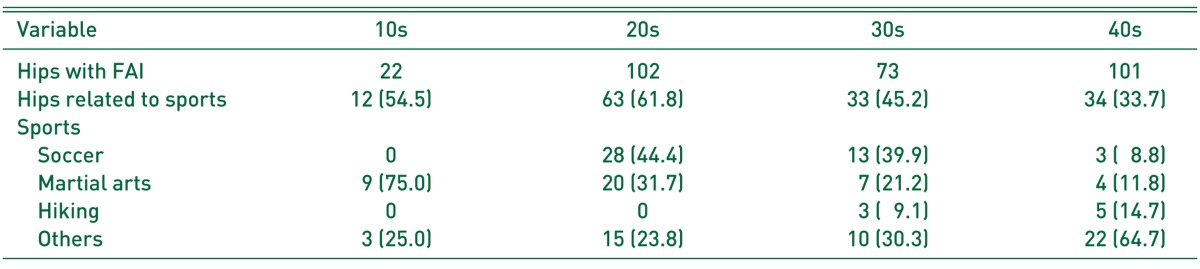

Table 1. Categorization of Femoroacetalbular Impingement (FAI) according to Ages.

Values are presented as number.

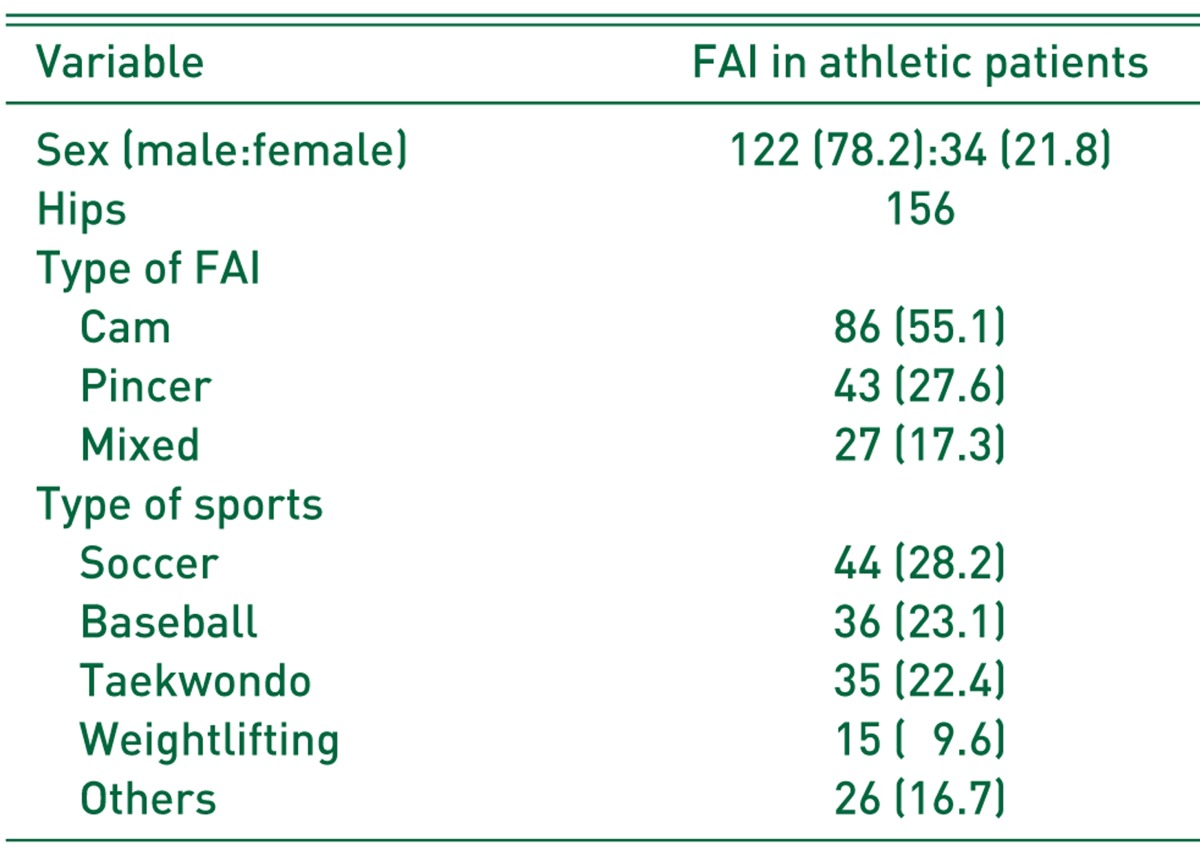

One hundred fifty-six hips (43.1%) were involved with sports in which male (122 hips, 78.2%) outnumbered female (34 hips, 21.8%). Among the 156 hips assessed in the present study, 86 hips (55.1%), 43 hips (27.6%), and 27 hips (17.3%) were categorized as cam, pincer, and mixed type, respectively. Type of sports were soccer, baseball and taekwondo which showed 44 (28.2%), 36 (23.1%) and 35 (22.4%) hips, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 4). Also, cases related to sports according to age were 63 hips (61.8%) for twenties and 12 hips (54.5%) for teenagers in which the two showed highest association to FAI. The kinds of sports that showed high association were 28 hips (44.4%) of soccer and 20 hips (31.7%) of martial arts such as taekwondo and judo for twenties and 9 hips (75.0%) of martial arts for teenagers which was the highest. Specific relationship was not able to be examined for the forties which showed diverse distribution of hiking (5 hips, 14.7%), taekwondo (4 hips, 11.8%) and other activities (Table 3).

Table 2. Prevalence of Femoroacetalbular Impingement (FAI) in Athletic Patients.

Values are presented number (%).

Fig. 4. A flowchart shows the process for selection of symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement in athletic patients among the patients who underwent arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement.

Table 3. Categorization of Sports according to Ages.

Values are presented number (%).

FAI: femoroacetalbular impingement.

DISCUSSION

FAI induces cartilage or acetabular labrum lesion, and ultimately could result in degenerative arthritis1,2,3). Up to now, there has been no study reporting long term results, but Ganz et al.1) reported that early diagnosis and treatments of FAI can prevent progression of hip joint arthritis. Particularly, athletes could be exposed to micro-injury constantly to intra-articular or structures around the joint due to the repetitive movement of a certain joint, and risk of hip joint injury due to excess movement range could be high, therefore chronic hip pain resulting from FAI could decrease the athletic ability19). And the close relationship between the FAI and sports have been verified in numerous studies5,6,20,21).

FAI is classified as cam type, pincer type, and mixed type which cam and pincer coexists18). Cam type is induced by powerful movements, particularly by abnormal impingement of acetabulum and femoral head-neck junction (deformation of femur characterized by findings of decreased offset of lateral femoral head-neck junction, anterolateral bony bump of femoral neck, coronoid deformation of femoral head-neck junction and bipartite line of femoral neck not crossing the femur midline) while flexing and internally rotating, and pincer type is induced by linear contact of abnormal acetabulum boundary (retroversion of acetabulum, coxa profunda and acetabular protrusio) and femur head-neck region.

As for the FAI relating to sports, Siebenrock et al.22,23) reported in the study on aggressive athletes playing baseball and ice-hockey that intense sports activity induces FAI, in particular the cam type which was dominant. In the present study, cam type was verified in 86 cases (55.1%) and sports had close relationship with FAI. Also, aggressive sports activity at an early age could result in FAI and chronic hip pain24), thus deciding the starting time and the kind of sports at an early age should be carefully made in case of findings of FAI after precise screening test and explanation on the risk of disorders.

Philippon et al.20) reported about the 93% of returning rate of 45 professional athletes after treatments with arthroscopic surgery on hip joint lesion including osteoplasty. Also, McCarthy et al.21) reported outstanding results of 80% of elite athletes and Byrd and Jones24) reported that modified Harris hip joint scores of 42 high school and university recreation athletes after arthroscopic treatment improve in all cases. Also, the present study showed most of patients returning to the prior level or close level of sports activity after surgery and at least 2 years of follow-up.

There were limitations to this study. First, the study has a patient bias due to geographical or institutional predominance. Thus, our results may be influenced by these errors. Second, we could not evaluate rate of return to sports. We determined only epidemiology of symptomatic FAI in athletes. Third, criteria of the athletic patients who were enrolled were not official. We defined the criteria through the consensus of all authors considering the general thought, because there was no reference about criteria of duration or frequency for definition of athlete. However, to our knowledge, there has not been any official paper regarding the relationship between sports activity and the prevalence of FAI.

CONCLUSION

FAI usually occurs in young adults and is highly related to sports activity. Most of the FAI type related to sports activity was cam type, and soccer and martial arts such as taekwondo were the most common cause of it.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112–120. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanzer M, Noiseux N. Osseous abnormalities and early osteoarthritis: the role of hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(429):170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tönnis D, Heinecke A. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1747–1770. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altenberg AR. Acetabular labrum tears: a cause of hip pain and degenerative arthritis. South Med J. 1977;70:174–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson K, Strickland SM, Warren R. Hip and groin injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:521–533. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290042501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philippon MJ, Schenker ML. Arthroscopy for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bizzini M, Notzli HP, Maffiuletti NA. Femoroacetabular impingement in professional ice hockey players: a case series of 5 athletes after open surgical decompression of the hip. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1955–1959. doi: 10.1177/0363546507304141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang C, Hwang DS, Cha SM. Acetabular labral tears in patients with sports injury. Clin Orthop Surg. 2009;1:230–235. doi: 10.4055/cios.2009.1.4.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laude F, Boyer T, Nogier A. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeyama A, Naito M, Shiramizu K, Kiyama T. Prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement in Asian patients with osteoarthritis of the hip. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1229–1232. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0742-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:423–429. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1012–1018. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tönnis D. Normal values of the hip joint for the evaluation of X-rays in children and adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;(119):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nötzli HP, Wyss TF, Stoecklin CH, Schmid MR, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:556–560. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b4.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tannast M, Siebenrock KA. Conventional radiographs to assess femoroacetabular impingement. Instr Course Lect. 2009;58:203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:281–288. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint with special reference to the complication of osteo-arthritis. Acta Chir Scand. 1939;58(Suppl):1–135. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tannast M, Siebenrock KA, Anderson SE. Femoroacetabular impingement: radiographic diagnosis--what the radiologist should know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1540–1552. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekström H, Elmståhl S. Pain and fractures are independently related to lower walking speed and grip strength: results from the population study "Good Ageing in Skåne". Acta Orthop. 2006;77:902–911. doi: 10.1080/17453670610013204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philippon M, Schenker M, Briggs K, Kuppersmith D. Femoroacetabular impingement in 45 professional athletes: associated pathologies and return to sport following arthroscopic decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:908–914. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0332-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy J, Barsoum W, Puri L, Lee JA, Murphy S, Cooke P. The role of hip arthroscopy in the elite athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(406):71–74. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000043046.84315.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siebenrock KA, Ferner F, Noble PC, Santore RF, Werlen S, Mamisch TC. The cam-type deformity of the proximal femur arises in childhood in response to vigorous sporting activity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:3229–3240. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1945-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siebenrock KA, Kaschka I, Frauchiger L, Werlen S, Schwab JM. Prevalence of cam-type deformity and hip pain in elite ice hockey players before and after the end of growth. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2308–2313. doi: 10.1177/0363546513497564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:749–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]