Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to compare preoperative clinical outcomes before occurrence of periprosthetic femoral fracture (status before trauma) with postoperative clinical outcomes (status after operation) in patients with periprosthetic femoral fracture after hip arthroplasty.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review was performed of all periprosthetic femoral fracture after hip arthroplasty treated surgically at our institution from January 2010 to January 2014. Among 29 patients who underwent surgical treatment for periprosthetic femoral fracture after hip arthroplasty, 3 patients excluded because of non-union of the fracture site. The clinical outcomes were determined by using visual analogue scale for pain (VAS), Harris hip score (HHS), and ambulatory ability using Koval classification. VAS, HHS and ambulatory ability was assessed for all the included patients at the last follow-up of status before trauma and after operation.

Results

The mean VAS, HHS and ambulatory ability at the last follow-up of status before trauma was 2.2 (range, 0-4), 78.9 (range, 48-92) and 1.9 (range, 1-5), respectively. The mean VAS, HHS and ambulatory ability at the last follow-up of status after operation was 3.1 (range, 1-5), 68.4 (range, 46-81) and 2.9 (range, 2-6), respectively. The clinical outcome of VAS, HHS and ambulatory ability were significantly worsened after surgical treatment for periprosthetic femoral fracture (P=0.010, P=0.001, and P=0.002, respectively).

Conclusion

Patients with periprosthetic femoral fracture after hip arthroplasty could not return to their status before trauma, although patients underwent appropriate surgical treatment and the fracture union achieved.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Clinical outcome, Hip, Periprosthetic fractures

INTRODUCTION

In 1954, periprosthetic femoral fracture in association with total hip arthroplasty (THA) was first reported1). Since then, during the past decade, the number of patients requiring THA has increased steadily in both younger patients and the more active elderly population2). There has been also a marked increase in hemiarthroplasty as treatment for femoral neck fractures3). As a result, the incidence of periprosthetic femoral fractures after hip arthroplasty is increasing4). A recent study showed that the incidence of periprosthetic femoral fracture is about 1% after primary THA and 4.2% after revision THA5,6). However, the treatment of periprosthetic femoral fractures continues to challenge orthopaedic surgeons.

Successful treatment of such periprosthetic femoral fractures varies from nonoperative procedures to extensive revision surgeries7), and many studies about periprosthetic fractures have been reported. However, there are few studies which compared between status of patient underwent hip arthroplasty before occurrence of periprosthetic fracture and status of patient underwent surgical treatment of periprosthetic femoral fracture.

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed consecutive cases underwent surgical treatment for periprosthetic femoral fracture after hip arthroplasty. The purpose of this study was to compare preoperative clinical outcomes before occurrence of periprosthetic femoral fracture (status before trauma) with postoperative clinical outcomes (status after operation) in patient with periprosthetic femoral fracture after hip arthroplasty.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Material

A retrospective review was performed of all periprosthetic femoral fracture after THA or bipolar hemiarthroplaty (BHA) treated surgically at our institution from January 2010 to January 2014. Only patients with complete medical record which included operation record and follow-up scoring and preoperative, postoperative and follow-up radiographs were included. Intraoperative fractures, concomitant infection, and fracture related to tumorous lesions were excluded. Patients with duration of follow-up less than 24 months after primary hip arthroplasty and surgical treatment for the periprosthetic fracture and with non-union of the periprosthetic fracture were also excluded for evaluation of clinical outcomes. Fracture union was defined radiologically as formation of callus on both anteroposterior and lateral radiographs8). Ethical approvals were obtained from the institutional review board of Chungnam National University School of Medicine (CNUH 2015-07-011).

2. Classification and Decision-making of Surgical Method

All operations including primary hip arthroplasty and surgical treatment for the periprosthetic femoral fracture were performed by a senior author. Decision-making for surgical options based on the Vancouver classification9,10,11,12,13). Twenty-nine patients who were categorized by Vancouver classification were included. Three patients (2 Vancouver type B1 fracture, 1 type C fracture) excluded because of non-union of the fracture site. They underwent reoperation for non-union at our institution. Union rate of the periprosthetic femoral fracture after THA or BHA was 89.7%. Therefore, 26 patients (9 males, 17 females) were identified. The affected side was 12 patients in right, 14 patients in left sides. Primary hip arthroplasty procedures were 10 patients of cementless THA and 16 patients of cementless BHA. The primary diagnosis for THA was avascular necrosis in 6 patients, femoral neck fracture in 1 patient, metal failure (compressive hip screw fixation due to femoral intertrochanteric fracture) in 1 patient, primary osteoarthritis in 1 patient and traumatic osteoarthritis (due to acetabular fracture) in 1 patient. And the primary diagnosis for BHA was fracture of femoral neck in 16 patients. Among those included in the analysis, the mean age at the time of the primary hip arthroplasty was 69.1 years old (range, 48-90 years) and the mean age at the time of the surgical treatment for periprosthetic femoral fracture was 74.6 years old (range, 53-92 years). The mean lag time between the primary hip arthroplasty and periprosthetic femoral fracture was 63.1 months (range, 25-155 months). According to Vancouver classification, there were 2 type A (all type AG), 19 type B (5 type B1, 11 type B2, and 3 type B3) and 5 type C (Table 1, 2).

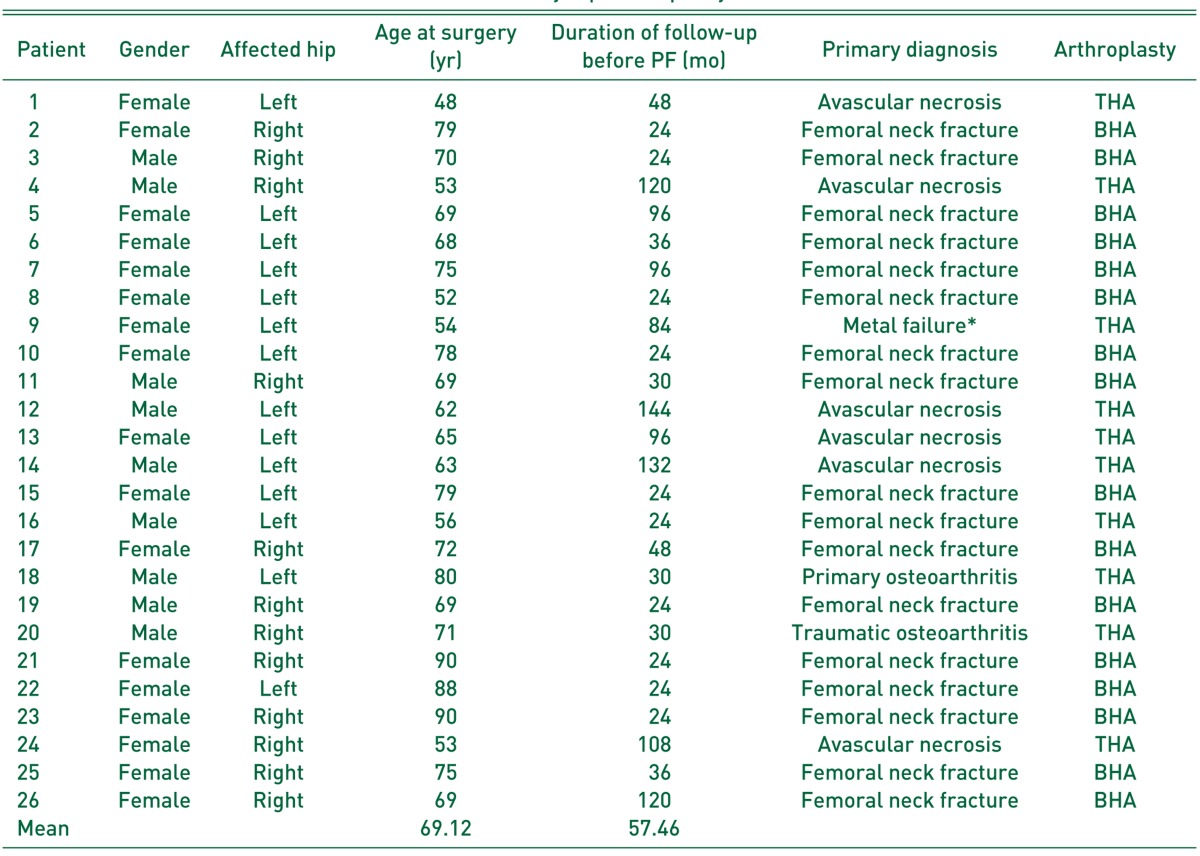

Table 1. Clinical Data of Patients Who Underwent Primary Hip Arthroplasty.

PF: periprosthetic fracture, THA: total hip arthroplasty, BHA: bipolar hemiarthroplasty.

*Failure of compressive hip screw fixation because of femoral intertrochanteric fracture.

Table 2. Clinical Data of Patients Who Underwent Treatment for Periprosthetic Femoral Fracture.

PF: periprosthetic fracture, BMD: bone mineral density, ORIF: open reduction and internal fixation.

*Lag time between primary hip arthroplasty and periprosthetic femoral fracture.

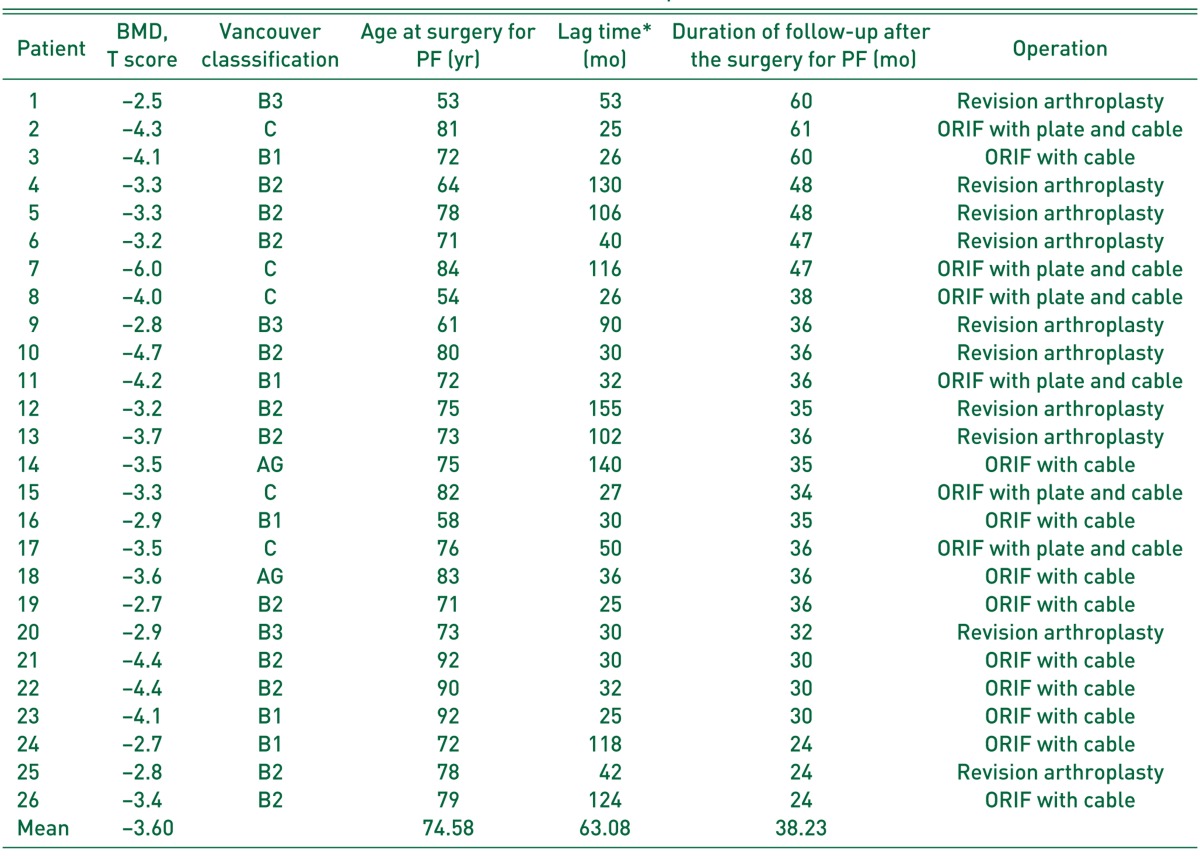

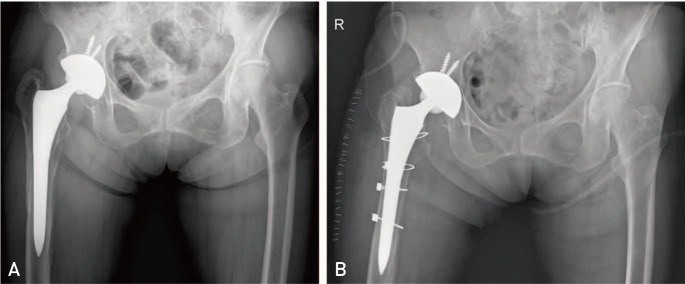

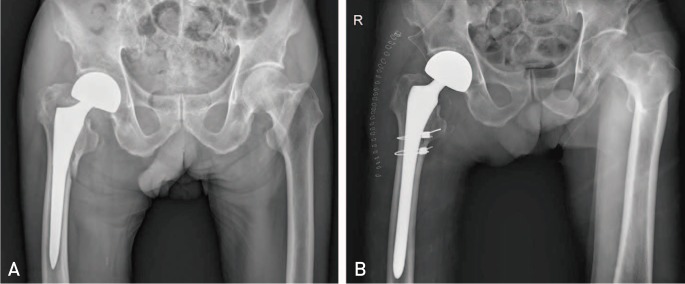

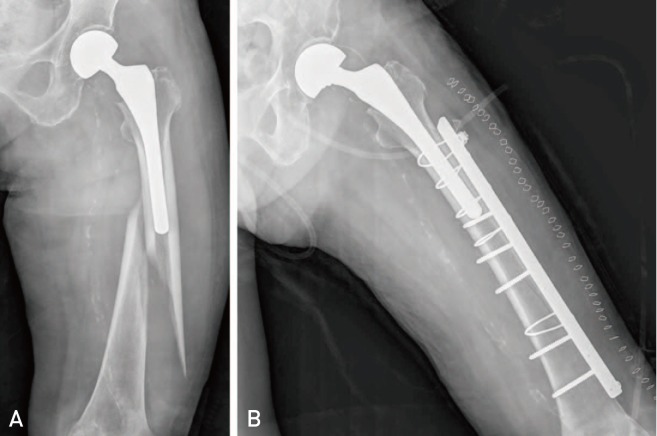

All patient in type AG fracture underwent cerclage wiring alone using Dall-Miles cable (Stryker Orthopaedics, Mahwah, NJ, USA). In the type B1 subgroup, 4 patients underwent open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with the cables (Fig. 1) and 1 patient underwent ORIF with plate and cable (Fig. 2). In the type B2 subgroup, 7 patients underwent cementless stem revision with the cables (Fig. 3) and 4 patients underwent ORIF with the cables. In the type B3 subgroup, all 3 patients underwent cementless longer stem revision with the cables. All 5 patients of type C were treated by ORIF with plate (Fig. 4, Table 2).

Fig. 1. (A) A plain hip radiograph of a 72-year-old female with periprosthetic fracture following primary total hip arthroplasty because of avascular necrosis of femoral head shows type B1 of Vancouver classification. (B) She underwent open reduction and internal fixation with the cables.

Fig. 2. (A) A plain hip radiograph of a 72-year-old male with periprosthetic fracture following primary total hip arthroplasty because of avascular necrosis of femoral head shows type B1 of Vancouver classification. (B) He underwent open reduction and internal fixation with NCB periprosthetic femur plate (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA) and the cables.

Fig. 3. (A) A plain hip radiograph of a 72-year-old male with periprosthetic fracture following primary bipolar hemiarthroplasty because of femoral neck fracture shows type B2 of Vancouver classification. (B) He underwent revision with U2 revision hip stem (United Orthopedic Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) with the cables.

Fig. 4. (A) A plain hip radiograph of a 84-year-old female with periprosthetic fracture following primary hemiarthroplasty because of femoral neck fracture shows type C of Vancouver classification. (B) She underwent open reduction and internal fixation with Cable-ready bone plate (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA) and the cables.

3. Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes

The clinical outcomes were determined by using visual analogue scale for pain (VAS), Harris hip score (HHS), and ambulatory ability using Koval classification14). All these parameters were assessed for all the included patients at the last follow-up of status before trauma and after operation. The ability was defined seven stages by Koval classification as follows: 1) independent community ambulation; 2) community ambulation with a cane; 3) community ambulation with a walker or crutches; 4) independent household ambulation; 5) household ambulation with a cane; 6) household ambulation with a walker or crutches; and 7) non-functional ambulation.

Bone mineral density (BMD) of all patients were evaluated after the surgical treatment. We have been evaluated BMD of patient with fracture around hip joint (Table 2).

4. Statistical Analysis

The differences between pre- and postoperative outcome measures were analyzed using the paired t-test for continuous outcome measures. And, we analyzed the correlation between the outcomes and age at the surgery for primary arthroplasty or for periprosthetic fracture or BMD using Pearson correlation. We rejected the null hypotheses of no difference if the P-values were less than 0.05. For the statistical analyses, we used the IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 19.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

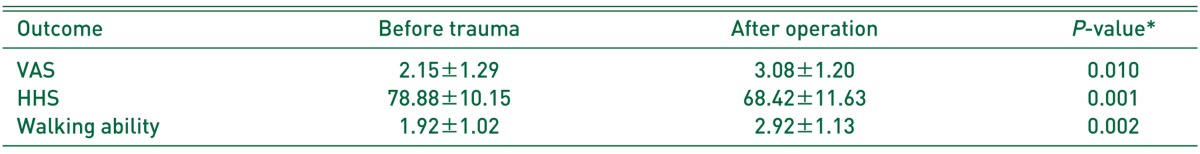

The mean VAS, HHS, and ambulatory ability at the last follow-up of status before trauma was 2.2 (range, 0-4), 78.9 (range, 48-92) and 1.9 (range, 1-5), respectively. The mean VAS, HHS, and ambulatory ability at the last follow-up of status after operation was 3.1 (range, 1-5), 68.4 (range, 46-81) and 2.9 (range, 2-6), respectively. The clinical outcome of VAS, HHS, and ambulatory ability were significantly worsened after surgical treatment for periprosthetic femoral fracture (P=0.010, P=0.001, and P=0.002, respectively) (Table 3). And, all patients had osteoporosis and the mean BMD was 3.6 g/cm2 (range, 2.5-6.0 g/cm2) (Table 2).

Table 3. Comparison Clinical Outcomes between the Status before Trauma and after Operation for Periprosthetic Femoral Fracture.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

VAS: visual analogue scale for pain, HHS: Harris hip score.

Walking ability was evaluated by Koval classification

*Based on separate paired t-test; P<0.05 denotes statistical significance.

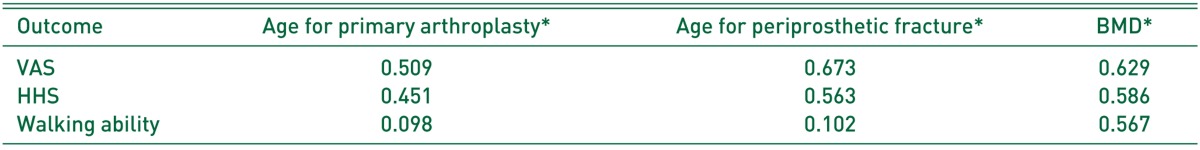

There were no correlation between age at the surgery for primary arthroplasty or for periprosthetic fracture or BMD and the final worsen outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4. Correlations between Worsened Outcomes and the Factors.

BMD: bone mineral density, VAS: visual analogue scale for pain, HHS: Harris hip score.

Walking ability was evaluated by Koval classification.

*Based on Pearson correlation; P<0.05 denotes statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

THA is an effective intervention for patients with severe hip disease and have been shown to lead to marked improvement in health outcomes15). Also, hemiarthroplasty is the most commonly recommended treatment for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in elderly patients16). On account of significant benefits realized with arthroplasty, the utilization rates of this procedure have been increasing globally17). However, patients who undergo arthroplasty take on the risks of several serious implant-related complications including dislocation, infection and periprosthetic fracture. Among those risks, the incidence of periprosthetic femoral fractures is increasing as a result of longer average lifespan and increasing number of arthroplasty procedures in older patients2,3,4). Therefore, orthopaedic surgeons have encountered more often those fractures and treatment of the fractures continues to challenge orthopaedic surgeons. And the treatment outcome of periprosthetic fractures has been coming into the picture. Consequently, we would evaluate the clinical outcomes and asked whether the clinical outcomes would be worsened after surgical treatment of periprosthetic femoral fracture comparing the outcomes before occurrence of periprosthetic femoral fracture.

The Vancouver classification is widely used as it is based on fracture location, implant stability and bone quality. Moreover, the classification has been validated and includes treatment algorithm11,12). However, this treatment algorithm based on the Vancouver classification lacks consideration of patient physiology and surgeon experience, which are also important factors for deciding treatment options18). Many studies presented orthopaedic surgeons should not recklessly follow the routine management algorithm 18,19,20). Vancouver type B2 fractures in this study underwent ORIF because of patients' other medical problems and general condition.

Several studies have found a union rate of periprosthetic femoral fracture ranging from 75% to 100%21,22,23,24,25). Similarly, this study showed union rate of the fracture was 89.7%. Moreta et al.21) reported that fracture union had been achieved in 92% of patients after the treatment (surgical or not) by the end of the follow-up. Moore et al.22) in their systematic review reported the union rate of Vancouver B1 fractures treated without allograft strut was 91.5%. García-Rey et al.23) reported all periprosthetic fractures of Vancouver B2 and B3 fractures healed. However, the clinical outcomes were poor, although the fracture union achieved. Scholz et al.24) and Young et al.25) reported postoperative mean HHS was 69.9 and 73.1, respectively. Although those studies did not compare between preoperative HHS before the fractures and postoperative HHS, the postoperative HHS was quite low. Moreover, this present study shows similar result that postoperative HHS was significantly worsened from 78.9 to 68.4, in spite of union of the fracture achieved. However, we could not find out the factors worsened outcomes. Moreta et al.21) described 52% of the patients did not return to their previous ambulatory levels. They reported there was no statistical differences in the final outcome as a function of the type of fracture, the method of treatment or the previous comorbidities. Therefore, the factors influenced the outcomes could be not simple and have not been come out into the open.

There were several limitations to this study. First, this study had a small cohort available for study. Therefore, we could not evaluate the relationship between the outcomes and the Vancouver classification or operative methods. Second, this study could not account for patients presenting to other medical problems such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and general condition. The clinical outcomes may be influenced by other problems. Therefore, future study should evaluate comorbidities and general conditions of patients such as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification26). Third, the study had a patient bias due to geographical or institutional predominance.

CONCLUSION

Patients with periprosthetic femoral fracture after hip arthroplasty could not return to their status before trauma, although patients underwent appropriate surgical treatment and the fracture union achieved.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Horwitz IB, Lenobel MI. Artificial hip prosthesis in acute and nonunion fractures of the femoral neck: follow-up study of seventy cases. J Am Med Assoc. 1954;155:564–567. doi: 10.1001/jama.1954.03690240030009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry DJ. Epidemiology: hip and knee. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadimitropoulos EA, Coyte PC, Josse RG, Greenwood CE. Current and projected rates of hip fracture in Canada. CMAJ. 1997;157:1357–1363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindahl H. Epidemiology of periprosthetic femur fracture around a total hip arthroplasty. Injury. 2007;38:651–654. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Springer BD, Berry DJ, Lewallen DG. Treatment of periprosthetic femoral fractures following total hip arthroplasty with femoral component revision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2156–2162. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200311000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meek RM, Norwood T, Smith R, Brenkel IJ, Howie CR. The risk of peri-prosthetic fracture after primary and revision total hip and knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:96–101. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.25087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindahl H, Oden A, Garellick G, Malchau H. The excess mortality due to periprosthetic femur fracture. A study from the Swedish national hip arthroplasty register. Bone. 2007;40:1294–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein GR, Parvizi J, Rapuri V, et al. Proximal femoral replacement for the treatment of periprosthetic fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1777–1781. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masri BA, Meek RM, Duncan CP. Periprosthetic fractures evaluation and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(420):80–95. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan CP, Masri BA. Fractures of the femur after hip replacement. Instr Course Lect. 1995;44:293–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rayan F, Dodd M, Haddad FS. European validation of the Vancouver classification of periprosthetic proximal femoral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1576–1579. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B12.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady OH, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Duncan CP. The reliability and validity of the Vancouver classification of femoral fractures after hip replacement. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(00)91181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park MS, Lim YJ, Chung WC, Ham DH, Lee SH. Management of periprosthetic femur fractures treated with distal fixation using a modular femoral stem using an anterolateral approach. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1270–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koval KJ, Skovron ML, Aharonoff GB, Meadows SE, Zuckerman JD. Ambulatory ability after hip fracture. A prospective study in geriatric patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;(310):150–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang RW, Pellisier JM, Hazen GB. A cost-effectiveness analysis of total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the hip. JAMA. 1996;275:858–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips JR, Moran CG, Manktelow AR. Periprosthetic fractures around hip hemiarthroplasty performed for hip fracture. Injury. 2013;44:757–762. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cram P, Lu X, Callaghan JJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cai X, Li Y. Long-term trends in hip arthroplasty use and volume. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:278–285.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beals RK, Tower SS. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur. An analysis of 93 fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(327):238–246. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199606000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SK, Kim YG, Kim SY. Treatment of periprosthetic femoral fractures in hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2011;3:101–106. doi: 10.4055/cios.2011.3.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niikura T, Lee SY, Sakai Y, Nishida K, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Treatment results of a periprosthetic femoral fracture case series: treatment method for Vancouver type b2 fractures can be customized. Clin Orthop Surg. 2014;6:138–145. doi: 10.4055/cios.2014.6.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreta J, Aguirre U, de Ugarte OS, Jáuregui I, Mozos JL. Functional and radiological outcome of periprosthetic femoral fractures after hip arthroplasty. Injury. 2015;46:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore RE, Baldwin K, Austin MS, Mehta S. A systematic review of open reduction and internal fixation of periprosthetic femur fractures with or without allograft strut, cerclage, and locked plates. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Rey E, García-Cimbrelo E, Cruz-Pardos A, Madero R. Increase of cortical bone after a cementless long stem in periprosthetic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3912–3921. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2845-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholz R, Pretzsch M, Matzen P, von Salis-Soglio GF. Treatment of periprosthetic femoral fractures associated with total hip arthroplasty. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2003;141:296–302. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young SW, Pandit S, Munro JT, Pitto RP. Periprosthetic femoral fractures after total hip arthroplasty. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:424–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Visnjevac O, Davari-Farid S, Lee J, et al. The effect of adding functional classification to ASA status for predicting 30-day mortality. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:110–116. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]