Abstract

Background

Attention deficit disorder/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a pathological condition that is not fully understood. In this study, we investigated electroencephalographic (EEG) power differences between children with ADHD and healthy control children.

Methods

EEGs were recorded as part of routine medical care received by 80 children with ADHD aged 4–15 years at the Department of Pediatric Neurology in Tottori University Hospital. Additionally, we recorded in 59 control children aged 4–15 years after obtaining informed consent. Specifically, awake EEG signals were recorded from each child using the international 10–20 system, and we used ten 3-s epochs on the EEG power spectrum to calculate the powers of individual EEG frequency bands.

Results

The powers of different EEG bands were significantly higher in the frontal brain region of those in the ADHD group compared with the control group. In addition, the power of the beta band in the ADHD group was significantly higher in all brain regions, except for the occipital region, compared with control children. With regard to developmental changes, the power of the alpha band in the occipital region showed an age-dependent decrease in both groups, with slightly lower power in the ADHD group. Additionally, the intergroup difference decreased in children aged 11 years or older. As with the alpha band in the occipital region, the beta band in the frontal region showed an age-dependent decrease in both groups. Unlike the alpha band, the power of the beta band was higher in the ADHD group than in the control group for children of all ages.

Conclusion

The observed intergroup differences in EEG power may provide insight into the brain function of children with ADHD.

Keywords: attention deficit disorder/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), electroencephalography (EEG)

Attention deficit disorder/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.1 ADHD is frequently treated with drugs such as methylphenidate and atomoxetine. The prevalence of ADHD among children is 5%, with a higher occurrence rate among boys.1 The initiation of treatment is often delayed because hyperactive children are regularly considered healthy active children in kindergarten and nursery settings.

The ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS), which is used in the diagnosis of ADHD, is essentially a tool in which parents or teachers assess the behavior of children. However, this assessment tool involves a degree of subjectivity, thus encouraging the development of more objective assessment methods. As the symptoms of ADHD persist into adulthood in half of children with ADHD,1 the early detection of ADHD is necessary to prevent social maladaptation. However, neurophysiological function in individuals with ADHD is poorly understood. In an electrophysiological study of children with ADHD, Puente et al. reported latency prolongation in waves I and III and a prolonged I–III and I–V interwave interval in auditory brainstem responses (ABR).2 In a study conducted by Miyazaki et al., seven of 18 children with ADHD had abnormal somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP), with giant SEPs in three of the children.3 In addition, several studies have examined electroencephalograms (EEG) in individuals with ADHD. For example, Kanazawa et al. observed epileptiform discharge and slow alpha in 22.1% and 18.6% of ADHD patients, respectively.4 In addition, based on EEG findings, Clarke et al. classified children with ADHD into: i) a maturational lag group, characterized by increased slow waves and decreased fast waves; ii) a cortical hypoarousal group, characterized by increased high amplitude theta waves and decreased beta waves; or iii) an over-aroused group, characterized by excess beta activity.5

In this study, we examined differences in central nervous system function in terms of EEG power between control children and children with ADHD who were awake, resting, and had their eyes closed.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects were 80 children (58 boys, 22 girls) aged 4–15 years who had been diagnosed with ADHD in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) at the Department of Pediatric Neurology in Tottori University Hospital between December 1993 and March 2007. We analyzed EEGs recorded prior to treatment with methylphenidate or atomoxetine. We included 23 children with ADHD who had EEG signals characterized by epileptic paroxysmal waves. For these children, we analyzed sections of EEG data without epileptic paroxysmal waves. In addition, 59 healthy children (31 boys, 28 girls) aged 4–15 years volunteered to participate in this study as control subjects. The control subjects and their parents were fully educated regarding the study objectives and they provided informed consent. To elucidate age-related changes, the ADHD and control subjects were divided into different age groups as follows: 4–6, 7–8, 9–10, 11–12, and 13–15 years (Table 1) and the powers were compared in each age group. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tottori University School of Medicine (approval number 2494).

Table 1.

Profiles of study subjects

| Age group (year) | Control | ADHD | ||||

| Number | Male : Female | Average age (year) | Number [EPW+] | Male : Female | Average age (year) | |

| Total | 59 | 31:28 | 8.7 | 80 [23] | 58:22 | 8.3 |

| 4–6 | 14 | 8:6 | 5.1 | 14 [4] | 10:4 | 5.5 |

| 7–8 | 12 | 2:10 | 7.4 | 37 [9] | 27:10 | 7.5 |

| 9–10 | 17 | 10:7 | 9.3 | 18 [6] | 12:6 | 9.4 |

| 11–12 | 10 | 7:3 | 11.3 | 6 [3] | 6:0 | 11.5 |

| 13–15 | 6 | 4:2 | 13.8 | 5 [1] | 3:2 | 13.6 |

ADHD, attention deficit disorder/hyperactivity disorder; EPW, epileptic paroxysmal wave.

We recorded EEGs using the Neurofax EEG-1200 monitoring system (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) with the time constant set at 0.3 sec, high cut filter at 60 Hz, sensitivity at 10 μV/mm, and sampling frequency at 200 Hz. In accordance with the international 10–20 system, disc electrodes were placed on the head of each subject, who was asked to rest in a supine position with their eyes closed. Contact impedance was set below 20 kΩ. We used MATLAB 8.1.0.604 software to analyze the spectra offline, and we calculated the mean power from ten 3-s epochs that were on the power spectrum of EEG with no paroxysmal waves and few artifacts.

The head was divided into the frontal (Fp1-F3, Fp2-F4), central (F3-C3, F4-C4), parietal (C3-P3, C4-P4), and occipital (P3-O1, P4-O2) regions, and bipolar leads were used to record the delta (0–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–20 Hz), and gamma (20–40 Hz) waves in each brain region. We compared the powers of the above frequency bands between ADHD and control children. However, the gamma band was difficult to discern, and so we only compared this variable between 41 ADHD and 49 control children who had less electromyographic noise in their EEGs. Before comparing the powers between the control and ADHD groups, we compared the powers between children with ADHD who had or did not have epileptic paroxysmal waves in their EEGs.

We averaged the power of the alpha band in the left and right occipital (P-O) regions and that of the beta band in the left and right frontal (Fp-F) regions, and then compared the mean powers between the ADHD and control groups.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics 21 software (IBM, Tokyo, Japan). We used the Mann–Whitney U test with the significance set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

We did not observe any significant differences between the ADHD group with epileptic paroxysmal waves and the ADHD group without epileptic paroxysmal waves, for all regions and frequency bands (P > 0.05). Therefore, children with ADHD with epileptic paroxysmal waves were included as ADHD subjects in this study.

Compared with the control group, the ADHD group had significantly higher mean delta (Fig. 1A) and theta (Fig. 1B) powers in the frontal and parietal regions. Children with ADHD also had significantly higher beta power (Fig. 1D) in all regions except for the occipital region, while alpha (Fig. 1C) and gamma (Fig. 1E) powers were significantly higher in an area that encompassed the frontal region. We observed significant group differences for the central theta and parietal alpha bands in the right hemisphere only.

Fig. 1.

Mean powers in different brain regions. ○, healthy children; ●, children with ADHD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

A: Comparison of delta power in different brain regions between the ADHD and control groups. The power of the delta band was significantly higher in the frontal (Fp1-F3, Fp2-F4) and parietal (C3-P3, C4-P4) regions in the ADHD group compared with the control group.

B: Comparison of theta power in different brain regions between the ADHD and control groups. The power of the theta band was significantly higher in the frontal (Fp1-F3, Fp2-F4), right central (F4-C4) and parietal (C3-P3, C4-P4) regions in the ADHD group compared with the control group.

C: Comparison of alpha power in different brain regions between the ADHD and control groups. The power of the alpha band was significantly higher in the frontal (Fp1-F3, Fp2-F4) and right parietal (C4-P4) regions in the ADHD group compared with the control group.

D: Comparison of beta power in different brain regions between the ADHD and control groups. The power of the beta band was significantly higher in the frontal (Fp1-F3, Fp2-F4), central (F3-C3, F4-C4) and parietal (C3-P3, C4-P4) regions in the ADHD group compared with the control group.

E: Comparison of gamma power in different brain regions between the ADHD and control groups. The power of the gamma band was significantly higher in the frontal (Fp1-F3, Fp2-F4) regions in the ADHD group compared with the control group.

ADHD, attention deficit disorder/hyperactivity disorder.

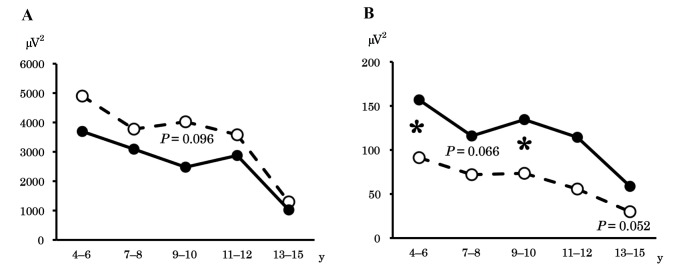

To clarify developmental changes in background EEG activity, we analyzed the mean power of the alpha band in the occipital region (Fig. 2A) in all age groups. The results revealed an age-dependent decrease in occipital alpha power in both the ADHD and control groups. This power was lower in children aged ≤ 10 years in the ADHD group compared with those in the control group, although this finding was insignificant. The intergroup difference diminished in older age groups. As with the occipital alpha band, the beta power in the frontal region (Fig. 2B), where the intergroup difference was prominent, decreased with age in both groups. However, unlike the occipital alpha band, the intergroup differences among children with ADHD were higher in all age groups, and we observed significant differences in the 4–6 and 9–10 years groups.

Fig. 2.

Mean power in different age groups. - -○- -, control group; –●–, ADHD group. *P < 0.05.

A: Age-related changes in occipital alpha power. The power of the alpha band in the occipital region decreased age-dependently in both the ADHD and control groups. Although occipital alpha power was lower (although this was not significant) in the ADHD group during early development, this difference decreased after the age of 11–12 years.

B: Age-related changes in frontal beta power. The power of the beta band in the frontal region decreased age-dependently in both the ADHD and control groups. For all age groups, children with ADHD exhibited higher power compared with the control group.

ADHD, attention deficit disorder/hyperactivity disorder; y, year(s).

DISCUSSION

Epileptic paroxysmal waves are known to be more frequently in children with ADHD compared with healthy children.3 In this study, we observed epileptic paroxysmal waves in 23 of the 80 children with ADHD. We decided to include children with ADHD who had EEG epileptic paroxysmal waves in our analysis because we found no significant differences in EEG power between children with ADHD with and without epileptic paroxysmal waves. This was the case when comparing by region and frequency band.

Comparison by region revealed that the powers of all frequency bands in the frontal region were significantly higher in children with ADHD compared with control children. This indicates the presence of a functional abnormality in the frontal brain area of children with ADHD. Shaw et al. conducted a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study and reported that the maturity of the prefrontal lobe in children with ADHD lags by up to 5 years.6 Decreased blood flow during a continuous performance test7 and decreased activity in the prefrontal lobe during the stop and delay task8 have also been reported in children with ADHD.

In terms of the parietal region, we found significantly higher delta, theta, alpha, and beta band power in the ADHD group compared with the control group. In a study conducted by Booth et al., functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed reduced brain activity in the parietal lobe among children with ADHD.9 This may reflect a functional abnormality in the parietal lobe in children with ADHD.

Comparisons by hemisphere revealed significant intergroup differences in central theta and parietal alpha power in the right hemisphere only. Consistent with this, cortical thinning in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex10 and a volume reduction in the right striatum11 have been reported in autopsy studies of children with ADHD.

As in the present study, many previous studies have reported global high theta wave power in children with ADHD.12–17 Elevated theta power in individuals with ADHD may reflect the maturational delay of the ADHD brain.18 Furthermore, our study revealed that the beta power was higher in the ADHD group in all brain regions except for the occipital region. It is generally known that mental excitability and tension increases the beta power. For example, Clarke et al. reported that moody children had increased beta wave activity.19 The increased beta power found in this study suggests a functional relationship between beta power and mental state in individuals with ADHD.

We compared developmental findings in different age groups. An intergroup difference in occipital alpha power was apparent in children aged ≤ 10 years, but not ≥ 11 years. This may be consistent with the Maturation Lag Model, which proposes that ADHD is caused by a maturational delay of the central nervous system.20 Conversely, frontal beta power was higher in children with ADHD compared with control children in all age groups. This may reflect the Developmental Deviation Model, which proposes that ADHD is caused by a functional abnormality in the central nervous system.20 Additionally, these findings suggest that occipital alpha power may reflect the hyperactivity characteristic of ADHD, as this generally decreases to normal levels during development, while frontal beta power may reflect an attention deficit, which seldom changes during development.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Ed, DSM-5. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. p. 61–63.61, 63. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Puente A, Ysunza A, Pamplona M, Silva-Rojas A, Lara C. Short latency and long latency auditory evoked responses in children with attention deficit disorder. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;62:45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miyazaki M, Fujii E, Saijo T, Mori K, Kagami S. Somatosensory evoked potentials in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and tic disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1286-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kanazawa O. Reappraisal of abnormal EEG findings in children with ADHD: on the relationship between ADHD and epileptiform discharges. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clarke AR, Barry RJ, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M. EEG-defined subtypes of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:2098-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, Blumenthal J, Lerch JP, Greenstein D, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19649-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amen DG, Carmichael BD. High-resolution brain SPECT imaging in ADHD. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1997;9:81-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubia K, Overmeyer S, Taylor E, Brammer M, Williams SC, Simmons A, et al. Hypofrontality in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during higher-order motor control: a study with functional MRI. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:891-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Booth JR, Burman DD, Meyer JR, Lei Z, Trommer BL, Davenport ND, et al. Larger deficits in brain networks for response inhibition than for visual selective attention in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:94-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Makris N, Biederman J, Valera EM, Bush G, Kaiser J, Kennedy DN, et al. Cortical thinning of the attention and executive function networks in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1364-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nakao T, Radua J, Rubia K, Mataix-Cols D. Gray matter volume abnormalities in ADHD: voxel-based meta-analysis exploring the effects of age and stimulant medication. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1154-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dupuy FE, Barry RJ, Clarke AR, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M. Sex differences between the combined and inattentive types of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an EEG perspective. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013;89:320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clarke AR, Barry RJ, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M, Magee CA, Johnstone SJ, et al. Quantitative EEG in low-IQ children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:1708-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barry RJ, Clarke AR, Hajos M, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M, Dupuy FE, et al. Resting-state EEG gamma activity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:1871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clarke AR, Barry RJ, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M. Age and sex effects in the EEG: differences in two subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:815-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clarke AR, Barry RJ, Dupuy FE, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M, Heaven PC. Childhood EEG as a predictor of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clarke AR, Barry RJ, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M, Brown CR, Croft RJ, et al. Effects of stimulant medications on the EEG of children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Predominantly Inattentive type. Int J Psychophysiol. 2003;47:129-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clarke AR, Barry RJ, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M. Age and sex effects in the EEG: development of the normal child. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:806-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clarke AR, Barry RJ, McCarthy R, Selikowitz M. Excess beta activity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an atypical electrophysiological group. Psychiatry Res. 2001;103:205-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barry RJ, Clarke AR, Johnstone SJ. A review of electrophysiology in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Qualitative and quantitative electroencephalography. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:171-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]