Abstract

Current estimates put the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Kenya at 5–8%. We determined the HBV infection prevalence in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–negative Kenyan adult and adolescent population based on samples collected from a national survey. We analyzed data from HIV-negative participants in the 2007 Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey to estimate the HBV infection prevalence. We defined past or present HBV infection as presence of total hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb), and chronic HBV infection (CHBI) as presence of both total HBcAb and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). We calculated crude and adjusted odds of HBV infection by demographic characteristics and risk factors using logistic regression analyses. Of 1,091 participants aged 15–64 years, approximately 31.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 28.0–35.3%) had exposure to HBV, corresponding to approximately 6.1 million (CI = 5.4–6.8 million) with past or present HBV infection. The estimated prevalence of CHBI was 2.1% (95% CI = 1.4–3.1%), corresponding to approximately 398,000 (CI = 261,000–602,000) with CHBI. CHBI is a major public health problem in Kenya, affecting approximately 400,000 persons. Knowing the HBV infection prevalence at baseline is important for planning and public health policy decision making and for monitoring the impact of viral hepatitis prevention programs.

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 240 million persons are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV).1,2 A recent global burden of disease study estimated that most sub-Saharan African countries, including Kenya, have a prevalence of chronic hepatitis B infection (CHBI) in the higher intermediate (5–7%) to high range (≥ 8%).1 Another recent study that performed a systematic review and pooled analysis estimated that the prevalence of CHBI for countries in the African region is 8.8%.2 However, in most low- and middle-income countries where hepatitis surveillance is limited, these estimates are based on data from sources that usually are not nationally representative. In Uganda, for example, a recent national HBV infection prevalence study found that the national prevalence is approximately 10%, ranging significantly by geographic region.3 In Kenya, studies have shown that there is a disparity in HBV infection prevalence by geographic area; one study found that the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence was 11.2% in eastern Kenya,4 and another study found the prevalence to be 8.8% in Turkana county,5 which is the largest and most northwestern county in Kenya. Studies of HBV infection prevalence in health-care settings may yield higher estimates due to selection bias. For example, a study by Pettigrew and others found that 77% of Kenyan patients at the liver clinic at the Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya, who had chronic aggressive hepatitis or cirrhosis also had HBsAg positivity.6

Knowing the baseline HBV infection prevalence is important for public health policy decisions and as a milestone to gauge the impact of disease prevention and control activities. However, during a time of competing needs where other diseases may take priority for resources, low- and middle-income countries usually lack the resources to implement a national hepatitis surveillance system. As a result, defining the national baseline prevalence of HBV infection in these countries is a daunting task, and other low-cost methods should be sought. If some resources are available, conducting hepatitis assessment surveys may be a suitable alternative for obtaining this information. However, when very little resources are available, other methods, including acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) indicator surveys and demographic and health surveys, can be used to collect and store serum samples from participants for the primary purpose of measuring the burden of HIV/AIDS, and additionally allows for integrating hepatitis testing for a minimal incremental cost. This study used a nationally representative AIDS indicator survey, the Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey (KAIS), as a way to measure the burden and factors associated with HBV infection in Kenya.

Materials and Methods

Survey design.

In 2007, KAIS, conducted by the Kenyan Ministry of Health, collected 1) interview data, which included information on demographics, sexual behavior, and healthcare-seeking behaviors and 2) sera from a nationally representative sample of consenting adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years in Kenya. The sampling frame for the KAIS 2007 was the National Sample Survey and Evaluation Program IV, a stratified, two-stage cluster sample design that was created by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.7 There were 294 (23%) rural and 121 (22%) urban clusters that were sampled, and an equal probability sampling method selected 25 households per cluster for a total of 10,375 households. More detailed information on the survey design for the KAIS 2007 is available from the KAIS 2007: final report.7

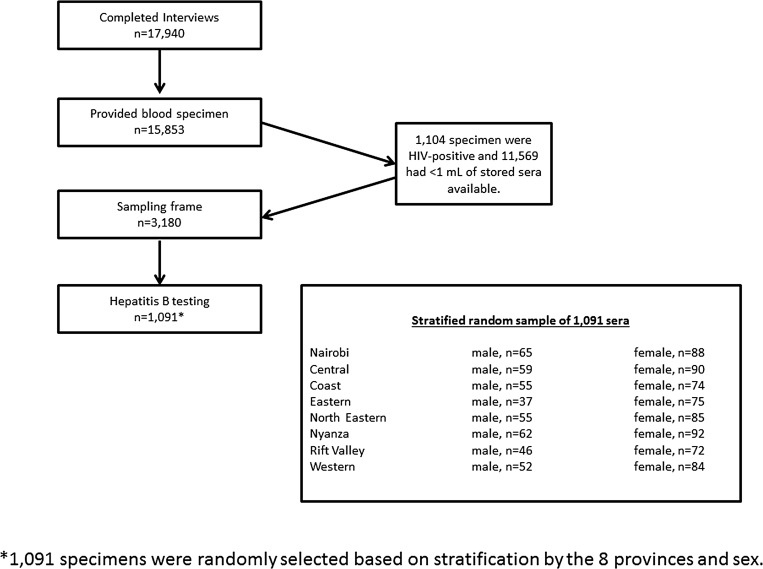

Because the survey was conducted primarily to measure HIV prevalence, all serum samples, which were obtained from venous blood, were first tested for HIV antibodies. HIV-positive specimens were exhausted from subsequent testing of HIV-associated biomarkers. As a result, only leftover HIV-negative samples were eligible for testing of other infectious agents of public health significance, including HBV infection. There were 3,180 specimens that were eligible for hepatitis testing, that is, were HIV negative and had ≥ 1 mL of stored sera. From these eligible specimens, an equal probability sampling method with stratification by residing province and sex was applied, which selected 1,091 specimens for hepatitis testing (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Sampling diagram of participants selected for hepatitis B testing in the Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey, 2007.

Laboratory testing.

HBV testing was conducted based on an algorithm. Specimens were initially tested for total hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb), which is a marker for exposure to HBV. Specimens that tested positive for total HBcAb were defined as having a past or present HBV infection. These specimens were then subsequently tested for HBsAg, and specimens that were positive for both total HBcAb and HBsAg were defined as having CHBI. HBV testing was conducted by the Hepatitis Reference Laboratory at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Viral Hepatitis using standard assays.

Data analysis.

SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 11.0; Research Triangle Park, NC) was the statistical software package used for these analyses. Prevalence estimates were weighted and adjusted using the appropriate survey weighting, clustering, and stratification variables to represent the overall HIV-negative adult and adolescent population aged 15–64 years in Kenya and to account for nonresponse to the questionnaire and serologic testing. Population extrapolations were calculated based on two numbers 1) the Kenya population aged 15–64 years in 2007 of 20.76 million persons obtained from statistics from the World Bank8 and 2) the 2007 HIV prevalence of 7.4% obtained from the KAIS 2007 final report.7 Therefore, the HIV-negative population for this age group in Kenya was estimated to total 19.23 million in 2007.

Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the odds of past or present HBV infection given select characteristics/factors. There were two categories of variables collected and measured in the univariate logistic regression models: 1) sociodemographic variables, which included residing province, rural/urban location, gender, age, education, and marital status, and 2) risk exposures/behaviors, which included blood transfusion, lifetime number of sexual partners, lifetime number of medical injections, sexual partner in the last 12 months, ever use of a condom, and ever given birth (females only). Parameter estimates were examined to evaluate statistical significance of the association between the outcome of past or present HBV infection and exposure of individual characteristics/factors. Candidate variables from univariate analysis with a P value less than 0.20 entered the multivariate logistic regression models. Associations where P values were less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Because of the small number of CHBI in this study (N = 27), we did not perform logistic regression analyses to determine the odds of chronic HBV infection. This study was approved by the Kenya Medical Research Institution Ethical Review Board and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of the 10,375 households sampled for the KAIS 2007 study, 9,691 households (93.4%), and 17,940 adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years completed the interview. Of persons interviewed, 15,853 (88.4%) provided blood specimens for testing of various infections and diseases (Figure 1). Of the 15,853 blood specimens collected, 3,180 specimens met the eligibility criteria for HBV testing, which required HIV negativity and ≥ 1 mL of stored sera. Of eligible specimens, 1,091 were randomly selected and tested for HBV.

Of the 1,091 participants who were tested for HBV, participants were approximately evenly distributed by province (10.8–14.1%). Participants most frequently resided in a rural area (72.0%), were female (60.5%), were aged 15–24 years (34.7%), had an incomplete or complete primary education (46.5%), had been in a relationship (69.9%), never had a blood transfusion (94.2%), had two or more sex partners (54.4%), never had any medical injections (66.4%), had a sex partner in the last 12 months (72.7%), and never used a condom (69.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and behavioral characteristics of adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years by HBV infection status, Kenya, 2007

| Category | Overall |

Current HBV infection* |

Past or present HBV infection† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | Weighted % (95% CI) | N | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 1,091 | 100.00 | 27 | 2.07 (1.36–3.13) | 365 | 31.52 (27.98–35.30) |

| Residing province | ||||||

| Nairobi | 153 | 14.02 | 0 | – | 41 | 27.60 (18.09–39.68) |

| Central | 149 | 13.66 | 4 | 2.72 (1.03–7.04) | 36 | 23.70 (17.88–30.70) |

| Coast | 129 | 11.82 | 4 | 3.19 (1.05–9.32) | 44 | 30.11 (21.15–40.89) |

| Eastern | 112 | 10.27 | 2 | 1.75 (0.42–7.07) | 41 | 35.10 (24.31–47.65) |

| North Eastern | 140 | 12.83 | 9 | 7.35 (3.76–13.88) | 84 | 60.84 (50.78–70.05) |

| Nyanza | 154 | 14.12 | 5 | 2.66 (1.18–5.86) | 53 | 36.28 (30.24–42.78) |

| Rift Valley | 118 | 10.82 | 3 | 1.85 (0.52–6.34) | 33 | 30.60 (20.37–43.17) |

| Western | 136 | 12.47 | 0 | – | 33 | 23.60 (16.54–32.50) |

| Rural/urban | ||||||

| Rural | 785 | 71.95 | 26 | 2.72 (1.78–4.13) | 284 | 33.65 (29.71–37.83) |

| Urban | 306 | 28.05 | 1 | 0.41 (0.06–2.93) | 81 | 26.09 (19.16–34.45) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 431 | 39.51 | 18 | 3.53 (2.15–5.76) | 145 | 30.69 (25.96–35.87) |

| Female | 660 | 60.49 | 9 | 1.16 (0.54–2.51) | 220 | 32.03 (27.52–36.91) |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 15–24 | 378 | 34.65 | 9 | 1.92 (0.94–3.90) | 66 | 17.81 (13.40–23.28) |

| 25–34 | 272 | 24.93 | 6 | 2.04 (0.86–4.79) | 87 | 30.08 (23.37–37.77) |

| 35–44 | 191 | 17.51 | 6 | 2.36 (0.91–6.01) | 78 | 37.36 (28.15–47.58) |

| 45–54 | 153 | 14.02 | 4 | 2.33 (0.80–6.57) | 82 | 53.89 (44.35–63.15) |

| 55–64 | 97 | 8.89 | 2 | 1.82 (0.39–7.96) | 52 | 50.86 (36.47–65.10) |

| Education‡ | ||||||

| No primary | 223 | 20.44 | 9 | 3.45 (1.57–7.41) | 114 | 47.55 (38.25–57.02) |

| Incomplete/complete primary | 507 | 46.47 | 12 | 1.86 (1.05–3.28) | 164 | 33.99 (29.30–39.02) |

| Secondary or higher | 361 | 33.09 | 6 | 1.78 (0.73–4.26) | 87 | 21.39 (16.17–27.73) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married or cohabitated | 328 | 30.06 | 5 | 1.46 (0.51–4.13) | 56 | 18.28 (13.69–24.00) |

| Formerly married or cohabitated | 130 | 11.92 | 3 | 1.44 (0.40–5.12_ | 51 | 32.93 (23.40–44.12) |

| Currently monogamous | 554 | 50.78 | 17 | 2.43 (1.43–4.08) | 220 | 37.18 (32.23–42.41) |

| Currently polygamous | 79 | 7.24 | 2 | 3.48 (0.95–11.92) | 38 | 50.68 (36.80–64.45) |

| Ever blood transfusion | ||||||

| Yes | 63 | 5.77 | 3 | 3.62 (0.89–13.54) | 26 | 33.68 (16.41–56.78) |

| No | 1,028 | 94.23 | 24 | 1.93 (1.24–2.98) | 339 | 31.33 (27.97–34.89) |

| Lifetime number of sex partners | ||||||

| No partner/never had sex | 148 | 13.91 | 2 | 0.38 (0.09–1.63) | 27 | 16.29 (10.69–24.05) |

| 1 partner | 337 | 31.67 | 7 | 1.42 (0.50–3.97) | 131 | 31.41 (25.08–38.52) |

| 2+ partners | 579 | 54.42 | 18 | 2.92 (1.82–4.66) | 196 | 34.61 (30.02–39.50) |

| Had sex partner in last 12 months? | ||||||

| Yes | 756 | 72.69 | 21 | 2.48 (1.55–3.95) | 258 | 33.64 (29.41–38.15) |

| No | 284 | 27.31 | 5 | 1.13 (0.40–3.17) | 78 | 24.16 (18.76–30.54) |

| Have you ever used a condom? | ||||||

| Yes | 268 | 30.45 | 9 | 3.29 (1.60–6.65) | 65 | 25.43 (18.83–33.39) |

| No | 612 | 69.55 | 14 | 1.81 (1.01–3.22) | 258 | 38.75 (33.97–43.75) |

| Lifetime number of medical injections | ||||||

| 0 | 724 | 66.36 | 19 | 2.21 (1.30–3.72) | 240 | 30.65 (26.52–35.12) |

| 1 | 95 | 8.71 | 0 | – | 37 | 33.37 (22.52–46.32) |

| 2–3 | 168 | 15.40 | 4 | 2.17 (0.75–6.11) | 48 | 29.19 (22.15–37.39) |

| ≥ 4 | 104 | 9.53 | 4 | 3.07 (1.37–6.73) | 40 | 39.14 (28.79–50.57) |

| Among females, ever given birth | ||||||

| Yes | 526 | 79.70 | 6 | 0.98 (0.41–2.32) | 193 | 34.81 (29.55–40.47) |

| No | 134 | 20.30 | 3 | 1.85 (0.38–8.59) | 27 | 21.53 (14.15–31.35) |

CI = confidence interval; HBV = hepatitis B virus. Specimens that were quantity not sufficient and missing values were excluded from this analysis.

Current HBV infection was defined as having a positive laboratory result for both hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) and the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).

Past or present HBV infection was defined as having a positive laboratory result for HBcAb.

Primary school is defined as elementary school usually from the ages of about 5 to 11 years. Secondary school is middle and high school usually from the ages 10 or 11 to 18 or 19 years.

The overall estimated prevalence of HBsAg among HIV-negative adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years in Kenya was 2.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.4–3.1%), corresponding to approximately 398,000 (CI = 261,000–602,000) persons with CHBI (Table 1). The estimated HBsAg prevalence was highest among persons who resided in the North Eastern Province (7.4%; 95% CI = 3.8–13.9%) followed by persons who ever received a blood transfusion, males, persons who were currently polygamous, persons who had no primary education, and persons who had ever used a condom.

The overall estimated prevalence of total HBcAb among HIV-negative adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years in Kenya was 31.5% (95% CI = 28.0–35.3%), corresponding to approximately 6.1 million (CI = 5.4–6.8 million) persons with past or present HBV infection (Table 1). The estimated total HBcAb prevalence was highest among persons who resided in the North Eastern Province, persons aged 45–54 and 55–64 years, persons who were currently polygamous, and persons who reported no primary education.

Factors independently associated with past or present HBV infection from univariate analyses are listed in Table 2. From multivariate analyses (Table 3), the adjusted relative odds of ever past or present HBV infection were significantly higher for persons residing in the North Eastern Province (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 4.19; 95% CI = 1.21–14.42) compared with those who resided in Nairobi; persons aged 35–44 (aOR = 2.66; 95% CI = 1.33–5.34), aged 45–54 (aOR = 6.44; 95% CI = 3.15–13.19), and aged 55–64 (aOR = 5.15; 95% CI = 2.24–11.84) years compared with those aged 15–24 years; and persons with some primary education (aOR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.13–3.16) compared with those with a secondary education or higher (Table 3).

Table 2.

Unadjusted relative odds of past or present HBV infection* among adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years, Kenya, 2007

| Category | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Residing province | |

| Nairobi | 1.00 (reference) |

| Central | 0.78 (0.40, 1.52) |

| Coast | 1.08 (0.52, 2.24) |

| Eastern | 1.40 (0.65, 3.01) |

| North Eastern | 4.62 (2.32, 9.21) |

| Nyanza | 1.55 (0.83, 2.88) |

| Rift Valley | 1.13 (0.51, 2.47) |

| Western | 0.78 (0.38, 1.59) |

| Rural/urban | |

| Rural | 1.46 (0.94, 2.28) |

| Urban | 1.00 (reference) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 0.94 (0.69, 1.26) |

| Female | 1.00 (reference) |

| Age group (years) | |

| 15–24 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 25–34 | 1.99 (1.24, 3.18) |

| 35–44 | 2.75 (1.62, 4.65) |

| 45–54 | 5.51 (3.29, 9.24) |

| 55–64 | 4.67 (2.34, 9.28) |

| Education† | |

| No primary | 3.55 (2.13, 5.93) |

| Incomplete/complete primary | 1.89 (1.25, 2.87) |

| Secondary or higher | 1.00 (reference) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married/cohabitated | 1.00 (reference) |

| Formerly married/cohabitated | 2.15 (1.15, 4.00) |

| Currently monogamous | 2.61 (1.75, 3.89) |

| Currently polygamous | 4.87 (2.52, 9.40) |

| Blood transfusion | |

| Yes | 1.09 (0.41, 2.85) |

| No | 1.00 (reference) |

| Lifetime number of sex partners | |

| No partner/never had sex | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 partner | 2.32 (1.29, 4.17) |

| ≥ 2 partners | 2.66 (1.56, 4.55) |

| Lifetime number of medical injections | |

| 0 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 | 1.13 (0.64, 2.00) |

| 2–3 | 0.92 (0.60, 1.39) |

| ≥ 4 | 1.50 (0.90, 2.51) |

| Had sex partner in last 12 months? | |

| Yes | 1.58 (1.09, 2.29) |

| No | 1.00 (reference) |

| Have you ever used a condom? | |

| Yes | 1.00 (reference) |

| No | 1.91 (1.25, 2.91) |

| Among females, ever given birth | |

| Yes | 1.95 (1.09, 3.49) |

| No | 1.00 (reference) |

CI = confidence interval; HBV = hepatitis B virus; OR = odds ratio.

Past or present HBV infection was defined as having a positive laboratory result for hepatitis B core antibody.

Primary school is defined as elementary school usually from the ages of about 5 to 11 years. Secondary school is middle and high school usually from the ages 10 or 11 to 18 or 19 years.

Table 3.

Significant adjusted relative odds of past or present HBV infection* of adults and adolescents aged 15–64 years, Kenya, 2007

| Category | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Residing province | |

| Nairobi | 1.00 (reference) |

| Central | 0.51 (0.20, 1.29) |

| Coast | 0.90 (0.38, 2.15) |

| Eastern | 1.07 (0.40, 2.91) |

| North Eastern | 4.19 (1.21, 14.42) |

| Nyanza | 1.22 (0.42, 3.54) |

| Rift Valley | 0.73 (0.27, 2.00) |

| Western | 0.40 (0.14, 1.12) |

| Age group (years) | |

| 15–24 | 1.00 (reference) |

| 25–34 | 1.85 (0.99, 3.45) |

| 35–44 | 2.66 (1.33, 5.34) |

| 45–54 | 6.44 (3.15, 13.19) |

| 55–64 | 5.15 (2.24, 11.84) |

| Education† | |

| No primary | 1.54 (0.78, 3.04) |

| Incomplete/complete primary | 1.89 (1.13, 3.16) |

| Secondary or higher | 1.00 (reference) |

CI = confidence interval; HBV = hepatitis B virus; OR = odds ratio.

Past or present HBV infection was defined as having a positive laboratory result for hepatitis B core antibody.

Primary school is defined as elementary school usually from the ages of about 5–11 years. Secondary school is middle, and high school usually from the ages 10 or 11 to 18 or 19 years.

Discussion

Our study found that the estimated prevalence of CHBI in Kenya was 2.1%, which represented approximately 400,000 persons with CHBI. CHBI prevalence was found to be disproportionately high among residents of the North Eastern Province, the reason for which is not clearly evident from this study but may be due to shared common cultural or traditional practices and/or risk factors. This survey was not able to obtain specific risk exposures/factors that were likely the cause of HBV infection because of the difficultly in determining when the risk exposure/factor and HBV infection occurred in time. However, these factors may contribute to a higher prevalence of HBV infection both in northeastern Kenya and in the bordering areas of Uganda where the prevalence CHBI among adults and adolescents is found to be very high (10.3%).3

The finding of a lower than previously estimated prevalence of CHBI in Kenya based on current estimates1 raises a question about the current estimates in sub-Saharan Africa generally and about the methods used to estimate HBV infection prevalence specifically. The prevalence estimates in most of these countries are based on data from small population, institution-based or nonrepresentative samples. Some analysts have also used the prevalence estimates of neighboring countries as a proxy for the prevalence in index countries. The data from Uganda3 and Kenya show that this approach could be flawed.

Although it may not explain the current CHBI prevalence, risk factors that can result in the acquisition or transmission of HBV infection are rampant. Although the pentavalent hepatitis B vaccine may have prevented transmission among infants and children, who are recommended to receive hepatitis B vaccination after the hepatitis B vaccine was introduced in Kenya in 2002, a significant proportion of the adult population remains at risk for acquiring HBV infection. In addition to targeted vaccination, other strategies to curb transmission include behavioral changes and education among at-risk populations.

The adverse outcomes of CHBI, including advanced liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, are high in Kenya. Other factors such as aflatoxin, alcohol consumption, and the use of herbal medicines could cause progression of liver disease in this population.9,10 The need for further investigation and treatment of CHBI is real but challenges in health service delivery are also significant.

This study has limitations. First, although our sample consisted of 1,091 participants who underwent HBV testing, the number of participants who were found to have CHBI was small (N = 27). The small number of persons with CHBI may create concerns about wider CIs around the CHBI estimates that were stratified by demographic and behavioral characteristics. Because we did observe relatively wider 95% CIs in some categories among persons with CHBI compared with persons who had past or present HBV infection, we limited the CHBI analyses to be descriptive. In addition, we were unable to perform any age stratifications due to the smaller number of persons found to have CHBI. Second, the overall sampling frame did not include persons aged < 15 or > 64 years. Therefore, we could not assess HBV infection among infants and children after the introduction of the hepatitis B vaccine in 2002 nor could we assess the burden of HBV infection among the elderly who, if chronically infected, are more at risk for developing liver cirrhosis and cancer. The impact of pentavalent hepatitis B vaccine in preventing HBV infection in vaccinated persons remains to be determined. Such a study would require a study design that includes persons born after the introduction of the vaccine into the country.11 Yet, we believe that the prevalence in the vaccinated population could actually be lower than the national average, that is, our estimate is an overestimate. Third, although Kenya has seen one of the worst HIV epidemics, because of the study design, our estimates did not include persons who were HIV infected. The HIV epidemic in Kenya is generalized with sexual transmission identified as the most common mode of transmission.12 The epidemiology of CHBI in Kenya, on the other hand, is not as well characterized, but studies in the literature suggest that HBV infections occurring during early childhood via horizontal transmission and iatrogenic exposure account for the majority of HBV infections in Africa.13 Based on the natural history of HBV infection, the risk of progressing to CHBI is inversely related to the age at the time of initial infection,14 and two non-nationally representative studies from Kenya found that the HBV infection rate is 6% among 378 HIV-positive patients attending a university hospital in Nairobi and 6.9% among 159 HIV-positive female sex workers receiving long-term antiretroviral therapy for HIV.13,15 In the United States, HBV is diagnosed among an estimated 10% of HIV-infected persons. Since the KAIS 2007 could not directly measure the prevalence of HIV/HBV coinfection, future studies are needed to determine the national prevalence of HIV/HBV coinfection in Kenya to supplement the CHBI prevalence estimated in this study. Despite these inherent limitations, we believe that the use of population-based data provides valuable information for determining the national burden of infection in countries where surveillance for these diseases is limited.

In conclusion, the burden of CHBI in Kenya is significant. This study established a national baseline prevalence for HBV infection among HIV-negative adults and adolescents and demonstrated the ability of nationally representative serosurveys to provide valuable information on the burden of HBV infection in Kenya. Understanding the baseline HBV infection prevalence is important for public health policy decision-making and for monitoring the impact of viral hepatitis prevention and control programs.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Footnotes

Financial support: The U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief funded this survey for specimen testing.

Authors' addresses: Kathleen N. Ly, Andrea A. Kim, Jan Drobenuic, John M. Williamson, Joel M. Montgomery, Barry S. Fields, and Eyasu H. Teshale, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mails: kathleen.ly@cdc.gov, aakim@cdc.gov, jdrobeniuc@cdc.gov, jwilliamson@cdc.gov, jmontgomery@cdc.gov, and bfields@cdc.gov. Mamo Umuro, National Public Health Laboratory Services, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya, E-mail: muromamo@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bwogi J, Braka F, Makumbi I, Mishra V, Bakamutumaho B, Nanyunja M, Opio A, Downing R, Biryahwaho B, Lewis RF. Hepatitis B infection is highly endemic in Uganda: findings from a national serosurvey. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9:98–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyams KC, Morrill JC, Woody JN, Okoth FA, Tukei PM, Mugambi M, Johnson B, Gray GC. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in eastern Kenya. J Med Virol. 1989;28:106–109. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890280210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mutuma GZ, Mbuchi MW, Zeyhle E, Fasana R, Okoth FA, Kabanga JM, Julius K, Shiramba TL, Njenga MK, Kaiguri PM, Osidiana V. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen and HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in Kenyans of various ages. Afr J Health Sci. 2011;18:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettigrew NM, Bagshawe AF, Cameron HM, Cameron CH, Dorman JM, MacSween RN. Hepatitis B surface antigenaemia in Kenyans with chronic liver disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1976;70:462–465. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(76)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National AIDS and STI Control Programme (Kenya), CDC Kenya, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United States Agency for International Development, U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, World Health Organization Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey, KAIS, 2007: Final Report. 2009. http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/12122/Share Available at. Accessed June 22, 2015.

- 8.The World Bank Population Ages 15–64 (% of total) 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.1564.TO.ZS/countries?page=1 Available at. Accessed April 16, 2015.

- 9.Yard EE, Daniel JH, Lewis LS, Rybak ME, Paliakov EM, Kim AA, Montgomery JM, Bunnell R, Abudo MU, Akhwale W, Breiman RF, Sharif SK. Human aflatoxin exposure in Kenya, 2007: a cross-sectional study. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2013;30:1322–1331. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2013.789558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu HC, Wang Q, Yang HI, Ahsan H, Tsai WY, Wang LY, Chen SY, Chen CJ, Santella RM. Aflatoxin B1 exposure, hepatitis B virus infection, and hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:846–853. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teshale EH, Kamili S, Drobenuic J, Denniston M, Bakamutamaho B, Downing R. Hepatitis B virus infection in northern Uganda: impact of pentavalent hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccine. 2015;33:6161–6163. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gumbe A, McLellan-Lemal E, Gust DA, Pals SL, Gray KM, Ndivo R, Chen RT, Mills LA, Thomas TK. KICoS Study Team Correlates of prevalent HIV infection among adults and adolescents in the Kisumu incidence cohort study, Kisumu, Kenya. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26:929–940. doi: 10.1177/0956462414563625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews PC, Gerettic AM, Gouldera PJR, Klenermana P. Epidemiology and impact of HIV coinfection with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Clin Virol. 2014;61:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon BJ, Alward WL, Hall DB, Heyward WL, Bender TR, Francis DP, Maynard JE. Acute hepatitis B virus infection: relation of age to the clinical expression of disease and subsequent development of the carrier state. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:599–603. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harania RS, Karuru J, Nelson M, Stebbing J. HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C coinfection in Kenya. AIDS. 2008;22:1221–1222. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830162a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]