Abstract

Herein, we report a case of fatal melioidosis in a newborn. The newborn died of serious melioidosis with respiratory and multiorgan failure at 16 days of age despite extensive treatment with antibiotics and methylprednisolone. Burkholderia pseudomallei was isolated from the infant's blood and cerebrospinal fluid and identified as a novel sequence type (ST-1341). His father had cough and fever when the newborn was born, and a localized patchy infiltration on the right upper lung was seen in chest radiography, but B. pseudomallei was not isolated. Two years later, the father developed cough and fever again, and the same novel sequence type of B. pseudomallei was isolated from the blood of the father. It is postulated that transmission of B. pseudomallei from the father to the newborn might have occurred during close contact in the first couple of days after birth. Given the high mortality of neonatal melioidosis, particular attention must be paid when the caretakers of the newborn develop fever of unknown origin in a melioidosis-endemic region.

Case Presentation

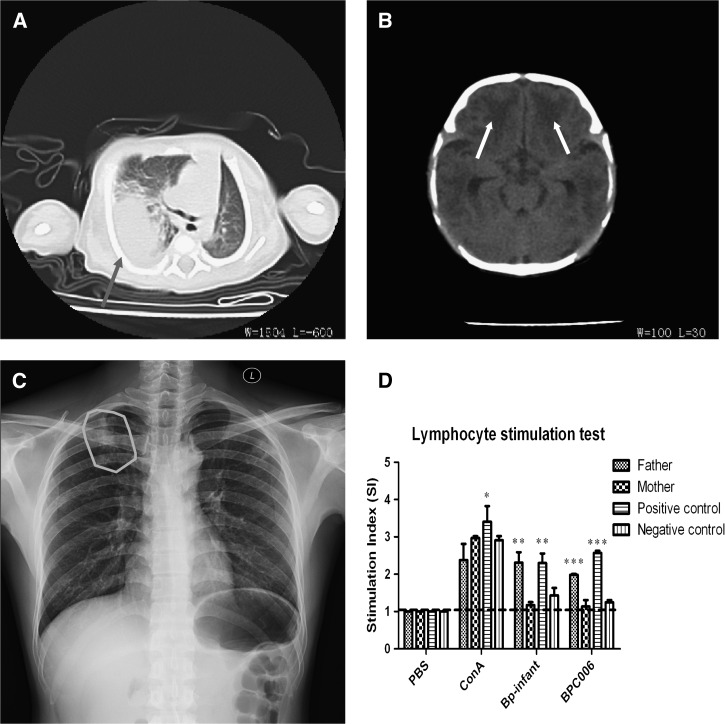

A male newborn born on July 6, 2013, at a local hospital in Sanya, Hainan Province, China, was discharged to home on the same day and stayed with his parents. One week later (July 13), the newborn developed a fever of unknown origin and became quite uncomfortable. He was treated with amoxicillin (0.35 g/day, intramuscular) and ibuprofen (400 mg every 4–6 hours, per os) for 3 days at a local children's hospital, but there was no remission. Instead, his temperature increased and exceeded 40°C, and he developed intermittent hyperspasmia for several hours. The newborn was transferred to the People's Hospital of Sanya, Hainan, on July 17. Computed tomography revealed multiple high-density foci in both lungs (Figure 1A ), especially in the right lung with bilateral pleural effusion. There was bilateral symmetrical diffusion of a low-density shadow in the frontal brain parenchyma (Figure 1B). To alleviate the severe symptoms, cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium (500 mg/day for both, intravenous [i.v.]) were administered empirically with human immunoglobulin (2.5 g/day, i.v.) and methylprednisolone (30 mg per kg weight, daily, i.v.). On July 19, the newborn suffered from respiratory distress. Burkholderia pseudomallei was cultured and identified in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid taken from the newborn on July 17. This was further confirmed using bioMérieux system (VITEK 2 Compact, Biomerieux, France) and 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene amplification and sequencing.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography images of the chest and brain of the newborn showing consolidated foci of infection in (A) the right lower lobe of the lung (dark gray arrow) and (B) the frontal brain parenchyma (black arrows). (C) Chest radiography of the newborn's father on July 22 showing localized patchy infiltration on his right upper lung (the gray circle). (D) Lymphocyte stimulation test showing a strong response to the ultrasound inactivated Burkholderia pseudomallei isolated from the newborn for the lymphocytes from his father and a recently diagnosed melioidosis-positive patient (a positive control), but not for the lymphocytes from his mother, a healthy person (a negative control), and Dulbecco's modified eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (blank control).

According to the subsequent drug sensitivity test, imipenem (1.5 g/day, i.v.) was used to replace other antibiotics on July 20. However, there was no alleviation of respiratory distress symptoms. On July 21, the newborn's blood oxygen level dropped to less than 85%, and there was significant coagulation abnormality with a D-dimer level of 1,897.29 mg/L. Activated partial thromboplastin time was 31.4 seconds. Ultrasound examination showed ascites and hepatomegaly. On the afternoon of July 22, the newborn's heart rate and blood oxygen level decreased further. At 6 pm, bloody discharge was observed in his mouth and nose, and the newborn showed little response to external stimuli. Dopamine combined with adrenalin (0.08 mg every 5 minutes, i.v.) was immediately administered, but without any effect. The newborn was declared clinically dead due to multiorgan failure at 9 pm, July 22.

Investigation of the B. Pseudomallei Isolates from the Newborn

The B. pseudomallei isolates cultured from the newborn's blood and cerebrospinal fluid were identified by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) to have identical allele profiles. They represent a novel sequence type (ST-1341: 1, 12, 14, 2, 1, 2, and 3), and the data have been deposited as BPC175 and BPC176 (http://bpseudomallei.mlst.net/).

To investigate possible sources of B. pseudomallei infection, we first reviewed the birth history of the newborn and the medical history of his parents, and then conducted microbiological examinations on his parents. The newborn was delivered through normal and natural labor without the need for intervention and weighed 2.6 kg at birth. He stayed at home with his parents after birth and was fed with both breast and powder milk. His parents were local farmers and had no chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, kidney dysfunction, or other immunosuppressive conditions. The 29-year-old mother had no suspected symptoms of melioidosis, and B. pseudomallei was not isolated from her cervical mucus and blood, which were negative for 16S rDNA amplification. The father, a 28-year-old, had cough and fever (38°C) when the newborn was born, and had had close contact with the newborn, but did not receive any medical treatment for his condition. He was advised to have further medical investigation. Chest radiography showed localized patchy infiltration on his right upper lung (Figure 1C). Subsequent cultures of possible respiratory infectious microorganisms, including B. pseudomallei, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and human immunodeficiency virus from blood or sputum specimens, were all negative.1 In addition, 16S rDNA amplification on his blood specimen was also negative. Persons who had any contact with the newborn all appeared healthy with no suspected symptoms, and cultures of their blood or sputum specimens were all negative for B. pseudomallei.

In addition, we explored other possible sources of B. pseudomallei infection by 16S rDNA amplification, such as the water and soil from the family's house and yard; his milk powder and bottle; medical instruments, the ward environment, the newborn incubator; his clothes, shoes, towels; and the skin of the parents, and all were negative for B. pseudomallei among soil,1 leaching liquor, or swab samples. As water is usually boiled before drinking in China, there was little likelihood that B. pseudomallei infection was from this source. Although we postulated that the father might have transmitted B. pseudomallei infection to the newborn, the infection source remains uncertain.

On June 3, 2015, 2 years after the infant's death, during a routine follow-up, the father developed symptoms similar to that of the previous onset, with cough and fever (39°C), but without any significant foci in lungs except for some lung markings (not shown). During the follow-ups, we did not Figure out exactly what was his risk factor for acquiring melioidosis, except for some drinking. Luckily, this time we succeeded in isolating B. pseudomallei from the father with the same MLST sequence type (ST-1341), which was also deposited as BPC177 (http://bpseudomallei.mlst.net/). The father was treated with meropenem (500 mg, every 8 hours, i.v.) and recovered 10 days later.

Furthermore, we conducted a lymphocyte stimulation test using ultrasound-inactivated B. pseudomallei from the newborn and lymphocytes from his parents, a melioidosis-positive patient (positive control), a healthy person (negative control), and Dulbecco's modified eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum as a blank control.2 A strong response to the inactivated B. pseudomallei was observed for lymphocytes from the newborn's father and the positive control, but not for lymphocytes from the newborn's mother and the negative and blank controls (Figure 1D).

Melioidosis, caused by the gram-negative B. pseudomallei present in the environment, is a disease of public health significance in southeast Asia and Australia and is associated with high case fatality and relapse rates in humans. The regional distribution of melioidosis within China is asymmetrical, with most cases in recent decades being encountered in local hospitals in Hainan Province, the most tropical area of the country.3,4 To our knowledge, this case of melioidosis is the youngest worldwide except for the maternal–neonatal vertical transmission case.5 We postulate that transmission of B. pseudomallei from the father to the newborn might have occurred during close contact in the first couple of days after birth, probably through respiratory dissemination of B. pseudomallei-contaminated aerosols. There is a possibility that the real source of B. pseudomallei was from the environment or the father's clothes transiently, since B. pseudomallei can be transmitted through aerosols. Higher resolution genetic typing such as multilocus variable number tandem repeat analysis or whole genome sequencing may help establish the link between father and infant.6 Given the high mortality of neonatal and childhood melioidosis,7–10 particular attention must be paid by those caring for the newborn, especially when the caretakers develop fever of unknown origin in a melioidosis-endemic region.

Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Third Military Medical University, which is a member of the Chongqing City Ethics Committees of China. Written informed consent was received from the newborn's parents.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Yao Fang and Xiong Zhu, Department of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology of Southwest Hospital, Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China, E-mails: fang-y2015@qq.com and yfangtiger@foxmail.com. Hai Chen and Xuhu Mao, Department of Clinical Laboratory, People's Hospital of Sanya City, Sanya, China, E-mails: 13677652433@139.com and 371095902@qq.com.

References

- 1.Limmathurotsakul D, Dance DA, Wuthiekanun V, Kaestli M, Mayo M, Warner J, Wagner DM, Tuanyok A, Wertheim H, Yoke Cheng T, Mukhopadhyay C, Puthucheary S, Day NP, Steinmetz I, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ. Systematic review and consensus guidelines for environmental sampling of Burkholderia pseudomallei. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, Wang L, Liu Y, Chen X, Liu Q, Jia J, Yang T, Qiu S, Ma G. Immune responses to vaccines involving a combined antigen-nanoparticle mixture and nanoparticle-encapsulated antigen formulation. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6086–6097. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang Y, Chen H, Li YL, Li Q, Ye ZJ, Mao XH. Melioidosis in Hainan, China: a retrospective study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109:636–642. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang S. Melioidosis research in China. Acta Trop. 2000;77:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbink FC, Orendi JM, de Beaufort AJ. Mother-to-child transmission of Burkholderia pseudomallei. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1171–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelle Wong Su Y, Lisanti O, Thibault F, Toh Su S, Loh Gek K, Hilaire V, Jiali L, Neubauer H, Vergnaud G, Ramisse V. Validation of ten new polymorphic tandem repeat loci and application to the MLVA typing of Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates collected in Singapore from 1988 to 2004. J Microbiol Methods. 2009;77:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumbiganon P, Pengsaa K, Puapermpoonsiri S, Puapairoj A. Neonatal melioidosis: a report of 5 cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:634–636. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lumbiganon P, Viengnondha S. Clinical manifestations of melioidosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:136–140. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saipan P. Neurological manifestations of melioidosis in children. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1998;29:856–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foong YW, Tan NW, Chong CY, Thoon KC, Tee NW, Koh MJ. Melioidosis in children: a retrospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:929–938. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]