Abstract

Despite overall global progress in tuberculosis (TB) control, TB remains one of the deadliest communicable diseases. This study prospectively assessed TB epidemiology in Lambaréné, Gabon, a Central African country ranking 10th in terms of TB incidence rate in the 2014 World Health Organization TB report. In Lambaréné, between 2012 and 2014, 201 adult and pediatric TB patients were enrolled and followed up; 66% had bacteriologically confirmed TB and 95% had pulmonary TB. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection rate was 42% in adults and 16% in children. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium africanum were identified in 82% and 16% of 108 culture-confirmed TB cases, respectively. Isoniazid (INH) and streptomycin yielded the highest resistance rates (13% and 12%, respectively). The multidrug resistant TB (MDR-TB) rate was 4/91 (4%) and 4/13 (31%) in new and retreatment TB cases, respectively. Treatment success was achieved in 53% of patients. In TB/HIV coinfected patients, mortality rate was 25%. In this setting, TB epidemiology is characterized by a high rate of TB/HIV coinfection and low treatment success rates. MDR-TB is a major public health concern; the need to step-up in-country diagnostic capacity for culture and drug susceptibility testing as well as access to second-line TB drugs urgently requires action.

Introduction

Despite the achievement of the 2015 Millennium Development Goal of halting and reversing tuberculosis (TB) incidence in all six regions of the World Health Organization (WHO), TB remains one of the deadliest infectious diseases.1 Improved diagnostic methods and enhanced surveillance data increasingly reveal the true burden of TB and the threatening dimension of drug-resistant (DR) TB. However, the overall success in tackling TB must not mask remaining major deficiencies in basic TB control faced by many countries with limited access to TB care.2 Underdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment translate into ongoing local transmission and emergence of resistance, while endangering global control efforts and global health. Central African nations rank among the countries with high TB and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) burden; Gabon ranks 10th in terms of incidence rate per 100,000 population in the 2014 WHO TB report.1 In contrast, disproportionately little data are available about local disease epidemiology, resistance pattern, and treatment outcomes.3

TB prevalence and HIV infection rate in Gabon are estimated at 578 per 100,000 and 4.1%, respectively.4,5 The country has been allocated support for TB control by the Global Fund only since 2015; until then, financing and operation of the national TB program has been under national responsibility.

Over the past few years, a TB research facility has been set up at the Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné (CERMEL) with support by the Pan-African Consortium for the Evaluation of Antituberculosis Antibiotics, a network of presently seven European and 11 African institutions who share the common vision of developing ground-breaking strategies in TB drug development. For the first time, this newly established TB diagnostic capacity facilitated the study of local TB epidemiology in a comprehensive prospective and systematic approach.

Here, we report on the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of TB in Lambaréné, Moyen Ogooué Province, Gabon, with focus on the main study objectives clinical presentation, treatment outcomes, and drug resistance.

Methods

This prospective observational cohort study was conducted at the TB laboratory of the CERMEL, a medical research unit located at the Albert Schweitzer Hospital (HAS).6 Patients were recruited at five different sites in Lambaréné: 1) in- and outpatient departments of HAS; 2) in- and outpatient departments of Georges Rawiri Regional Hospital (CHRGR); 3) local outpatient HIV clinic (Centre de Traitement Ambulatoire [CTA]); 4) local outpatient TB clinic (Base d'épidémiologie [BELE]); and 5) CERMEL; thus representing all “ports of entry” for TB patients into the local health-care system (catchment area of approximately 50,000 people).

Patients who presented with symptoms of active TB and who were initiated on TB treatment were asked to participate. Eligible patients were identified at ward rounds, outpatient consultations, or through samples submitted to the laboratory for TB diagnostics. Demographic and clinical data were collected by study investigators. Bacteriological confirmation of TB was based on the examination of one spot sputum, and two further morning sputum samples and examination of extrapulmonary specimens for suspected extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) cases. Clinically diagnosed TB cases were identified based on presentation of signs and symptoms of TB as per national guidelines.7 Further routine testing included full blood count and basic biochemistry. As per national guidelines, all patients enrolled into the study were strongly advised to undergo HIV testing, which was performed using Determine HIV 1/2 (Inverness Medical Innovations, Waltham, MA) and Vikia HIV-1/2 (Standard Diagnostics, Kyonggi-do, South Korea) rapid immunochromatographic parallel testing. The p24 antigen test Mini Vidas (Biomérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) was used for discordant results. TB work-up further comprised tuberculin skin testing (TST; result recorded as positive if induration ≥ 10 mm in HIV-uninfected and ≥ 5 mm in HIV-infected patients), chest X-ray (CXR) interpreted by the attending physician, and further imaging examinations if clinically indicated. Patients diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed TB were initiated on TB treatment by the attending physician according to the national TB program guidelines7; standard treatments were 2RHZE/4RH (which is 2 months treatment with rifampicin [RIF], isoniazid [INH], pyrazinamide [PZA], and ethambutol [EMB] followed by 4 months RIF and INH) for new TB cases, 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RH (2 months of RIF, INH, PZA, EMB, and streptomycin [STR] followed by 1 month of RIF, INH, PZA, and EMB followed by 5 months of RIF and INH) for retreatment TB patients, and 2RHZ/4RH (2 months treatment with RIF, INH, and PZA followed by 4 months RIF and INH) for children below the age of 8 years. Second-line regimen guidelines and second-line drugs to treat DR-TB were not available in Gabon when conducting this study.2

The attending care provider coordinated and supervised TB treatment, while study investigators recorded the duration and regimens of TB treatment. Patients were followed up at 2 (M2) and 6 (M6) months. In case of a missed follow-up appointment, the patient was contacted by phone. If this was unsuccessful, follow-up data were retrieved from patient records of the attending health facility if available. Sputum sample collection for bacteriological testing at M2 and M6 was attempted for all patients, and further diagnostic evaluations were initiated by the attending health facility if clinically indicated, or initiated by the attending health facility. For classification of treatment response, only follow-up data collected on M2 ± 1 and M6 ± 1 month after treatment initiation was included into the analysis. In cases where the patient had to continue treatment after M6, follow-up was continued until the termination of TB treatment, and end-of-treatment data were included in the analysis.

Ethical considerations.

This study was approved by the scientific review committee and the institutional ethics committee of the CERMEL in June 2012. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients (or legal guardians in case of children) before study enrollment. All results of laboratory analysis performed in the context of the study were reported back to the respective attending health facilities.

Mycobacteriology.

Samples for mycobacterial investigation were first analyzed by microscopy as per national guidelines.7 Both conventional Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) and auramine fluorochrome staining were used for light and fluorescence microscopy (FM), respectively.8 Samples were later referred to a supranational laboratory, the German National Reference Center for Mycobacteria in Borstel, Germany, for liquid mycobacterial culture (by mycobacteria growth indicator tube [MGIT]; BACTEC MGIT 960 TB System; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), drug susceptibility testing (DST) and species analysis. Mycobacterial species differentiation was performed on positive cultures by the GenoType MTBC assay (Hain Life Sciences, GmbH Germany). Cultures identified as Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex were tested for sensitivity to first-line drugs RIF, INH, EMB, PZA, and STR, using the MGIT culture tube manual system according to the manufacturer's instructions (BBLTM MGIT™ SIRE and PZA test kits; Becton Dickinson). In case of any resistance to first-line drugs, DST was also performed for the following second-line drugs: ethionamide (ETO), ofloxacin (OFX), cycloserine (CS), amikacin, 4-aminosalicylic acid (PAS), and capreomycin.

Case and variable definitions.

Case definitions for adult TB patients were based on WHO's Definitions and Reporting Framework for Tuberculosis—2013 Version.9 Case definitions for childhood TB (age below 18 years) were based on the criteria of Graham and others.10 Drug resistance was classified as mono-resistance (resistance to one first-line anti-TB drug only), poly-resistance (resistance to more than one first-line anti-TB drug other than both INH and RIF), and multidrug resistance (MDR) (resistance to at least both INH and RIF). Survival was documented if any information on the patient being alive at M6 ± 1 month or later was available. Rural residence was defined as living in villages or towns smaller than Lambaréné. “High infectiousness” was defined as microscopic sputum smear positivity with ≥ 3+8; and “unfavorable treatment outcome” was defined as “outcome classification other than treatment success” excluding patients with MDR-TB.

Data management and statistics.

Clinical and demographic data were entered into OpenClinica (version 3.0.4; OpenClinica®, Boston, MA); microbiology data were entered in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Data were analyzed using R Statistical software version 3.1.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For descriptive statistics means and standard deviations (SDs), medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and proportions were calculated. The likelihood ratio test was used to test the linear trend for continuous variables. Univariate logistic regression was used to calculate crude odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Stepwise selection with the Akaike information criterion was used to select the factors for the multivariate logistic regression model for calculation of the adjusted ORs (aORs) with 95% CI. Using the Mantel–Haenszel method, confounding was investigated for risk factors with at least a 20% significant modification between crude and aOR. Missing data analysis was performed for variables with more than 15% missing data using multiple imputations by chained equations.

Results

Baseline demographics.

From June 2012 to October 2013, 723 TB suspected patients submitted specimens to the TB laboratory for TB microscopy and culture; in addition, 55 patients were clinically investigated for active TB without microbiological analyses (patients unable to produce sputum samples). A total of 201 patients with microbiologically or clinically diagnosed active TB, who commenced antituberculous treatment, were enrolled in the study; 103 (51%) were enrolled at HAS, 50 (25%) at CHRGR, 28 (14%) at CERMEL, 15 (7%) at CTA, and five (3%) at BELE. Of these patients, 170 (85%) were adults and 31 (15%) were children younger than 18 years. The male-to-female ratio was 1.18. Twenty-five (12%) patients sought care for TB in Lambaréné, despite other TB treatment centers being closer to their residency. Baseline demographic data including sex, age, HIV status, and distance to TB treatment center are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of 201 TB patients in Lambaréné (2012–2013)

| Total cohort | Adults | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort, n (%) | 201 (100) | 170 (85) | 31 (15) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 92/201 (46) | 80/170 (47) | 12/31 (39) |

| Median age, years (IQR)* | 32.0 (22.6–42.1) | 36.3 (26.9–43.3) | 6.1 (2.0–15.4) |

| HIV infected, n (%) | 70/183 (38) | 66/158 (42) | 4/25 (16) |

| New HIV diagnosis, n (%) | 22/183 (12) | 20/158 (13) | 2/25 (8) |

| Median CD4 counts, cells/μL (IQR)† | 130 (56–227) | 130 (56–227) | NA |

| Rural residence, n (%) | 69/201 (34) | 61/170 (36) | 8/30 (26) |

| Distance to TB care < 5 km, n (%)‡ | 110/184 (60) | 90/154 (58) | 20/30 (67) |

CD4 = cluster of differentiation 4; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IQR = interquartile range; NA = not available; TB = tuberculosis.

Data available for 200 patients.

Data available for 51 (73% of HIV infected) patients.

Distance to TB care < 5 km represents living within Lambaréné.

Clinical and mycobacterial baseline determinants of TB.

Baseline characteristics related to TB (contact with TB index case, symptoms, clinical findings, hemoglobin levels, prior non-antituberculous antibiotics, CXR findings, and TST) and baseline mycobacteriology are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline determinants related to tuberculosis and baseline mycobacteriology in Lambaréné (2012–2013)

| Total cohort | Adults | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort, n (%) | 201 (100) | 170 (85) | 31 (15) |

| TB index case known, n (%) | 72/189 (38) | 48/160 (30) | 24/29 (83) |

| Main TB contact | Family member | Sibling | Parent |

| Reported TB symptoms | |||

| Weight loss, n (%) | 173/199 (87) | 151/169 (89) | 22/30 (73) |

| Mean weight loss, kg (SD)* | NA | 8.0 (6.5) | 3.7 (2.5) |

| Cough, n (%) | 167/200 (84) | 143/170 (84) | 24/30 (80) |

| Fever, n (%) | 162/198 (82) | 138/169 (82) | 24/29 (83) |

| Night sweat, n (%) | 100/194 (52) | 88/168 (52) | 12/26 (46) |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 76/200 (38) | 69/170 (41) | 7/30 (23) |

| Hemoptysis, n (%) | 44/197 (22) | 43/168 (26) | 1/29 (3) |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 43/200 (22) | 40/170 (24) | 3/30 (10) |

| Median duration of cough, days (IQR)† | 30 (21–90) | 30 (21–90) | 26 (14–128) |

| Clinical examination | |||

| Pathologic lung auscultation, n (%) | 136/188 (72) | 120/162 (74) | 16/26 (62) |

| Axillary temperature > 37.5°C, n (%) | 77/162 (48) | 71/142 (50) | 6/20 (30) |

| Palpable lymphadenopathy, n (%) | 36/188 (19) | 28/160 (18) | 8/28 (29) |

| BMI, mean (SD)‡ | NA | 18.9 (2.8) | NA |

| Children < 3rd/5th percentile, n (%)§ | NA | NA | 5/20 (25) |

| Hemoglobin, mean g/dL (SD) | 9.8 (2.2) | 10.0 (2.3) | 8.1 (2.2) |

| Prior non-antitubercular antibiotics, n (%) | 74/113 (66) | 65/98 (66) | 8/14 (57) |

| Most frequent antibiotics | NA | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, co-trimoxazole | Gentamycin |

| Pathologic chest X-ray, n (%) | 171/177 (97) | 144/148 (97) | 27/29 (93) |

| Infiltrates, n (%) | 144/177 (81) | 122/148 (82) | 22/29 (76) |

| Cavitations, n (%) | 56/177 (32) | 51/148 (35) | 5/29 (17) |

| Hilar lymphadenopathy, n (%) | 55/177 (31) | 43/148 (29) | 12/29 (41) |

| Pleural effusion, n (%) | 21/177 (12) | 19/148 (13) | 2/29 (7) |

| Positive TST, n (%) | 36/58 (62) | 26/41 (63) | 10/17 (59) |

| Mycobacteriology performed, n (%) | 179/201 (89) | 164/170 (97) | 15/31 (48) |

| Positive sputum microscopy∥ | 125/173 (72) | 119/160 (74) | 6/13 (46) |

| Ziehl–Neelsen stain ≥ 3+ | 31/155 (20) | 29/144 (20) | 2/11 (18) |

| Positive sputum culture | 105/150 (70) | 98/138 (71) | 7/12 (58) |

| Positive extrapulmonary sample microscopy∥ | 1/10 (10) | 1/8 (13) | 0/2 |

| Positive extrapulmonary sample culture | 4/8 (50) | 4/7 (57) | 0/1 |

| Total positive mycobacteriology¶ | 134/179 (75) | 126/164 (77) | 8/15 (53) |

| PCR and DST | |||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis, n (%) | 89/108 (82) | 83/101 (82) | 6/7 (86) |

| Mycobacterium africanum, n (%) | 17/108 (16) | 16/101 (16) | 1/7 (14) |

| Mycobacterium intracellulare, n (%) | 2/108 (2) | 2/101 (2) | 0/7 |

| Drug-sensitive TB, n (%) | 88/105 (84) | 82/98 (84) | 6/7 (86) |

| Mono-resistance, n (%) | 7/105 (7) | 6/98 (6) | 1/7 (14) |

| Poly-resistance, n (%) | 2/105 (2) | 2/98 (2) | 0/7 |

| MDR, n (%) | 8/105 (8) | 8/98 (8) | 0/7 |

BMI = body mass index; DST = drug susceptibility testing; IQR = interquartile range; MDR = multidrug resistance; NA = not available; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; SD = standard deviation; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Data available for 58 adults and 11 children.

Data available for 143 adults and 21 children.

Data available for 109 patients.

Percentiles based on growth charts by World Health Organization: 3rd percentile for children < 2 years of age and 5th percentile for children ≥ 2 years of age.

Using Ziehl–Neelsen and/or auramine fluorochrome stain.

Confirmed by microscopy or culture.

Sputa were available for 160 (94%) adults and 13 (42%) children. Sputum smear microscopy and culture were performed on three, two, or one sputum sample(s) in 68%, 23% and 9% of patients, respectively. The positivity rate of sputum samples investigated by ZN microscopy was 63% and 36% for adults and children, respectively. The additional use of FM increased the positivity rate to 74% and 46%, respectively. Of patients who submitted one sputum sample only, 14 of 16 were positive. Cultures were performed for 166 (83%) patients, of which eight (5%) were contaminated. Of 125 microscopy positive patients, 17 (14%) cultures were negative; of 48 microscopy negative patients, nine (19%) cultures were positive. Mean time span between sample collection and culture result availability was 2.9 (SD = 0.8) months.

EPTB samples were investigated for eight adults and two children. Specimen from adults comprised four pleural fluids, two lymph node aspirates, one pericardial fluid, and one cerebrospinal fluid. From children, one lymph node aspirate and one gastric aspirate were available. Of nine patients classified as EPTB, four (44%) were HIV infected.

DST was performed for 105 cultures and revealed drug resistance in 17 (16%) cases; resistance profile and clinical information are presented in Table 3. Among culture-confirmed TB patients, the MDR-TB rate was 4/91 (4%) and 4/13 (31%) in new and previously treated TB patients, respectively (overall MDR-TB rate was 8/105 (8%). No extensively drug resistant TB was observed.

Table 3.

Drug resistance patterns of mono-, poly- and multidrug-resistant TB isolates in Lambaréné (2012–2013)

| RIF | INH | PZA | EMB | STR | OFX | ETO | CS | AM | PAS | CM | Species | Clinical information (history of TB; outcome9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono-resistance to first-line drugs (N = 7) | |||||||||||||

| n = 2 | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | Mtb | New TB; not evaluated (1), completed (1) |

| n = 1 | S | R | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | Mtb | New TB; lost to follow-up |

| n = 1 | S | R | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | Maf | New TB; completed |

| n = 3 | S | S | S | S | R | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Mtb | New TB (1), retreatment (2); completed (2), cured (1) |

| Poly-resistance to first-line drugs (N = 2) | |||||||||||||

| n = 1 | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | Mtb | New TB; completed |

| n = 1 | S | R | S | S | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | Maf | New TB; cured |

| Multidrug resistance (N = 8) | |||||||||||||

| n = 1 | R | R | S | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | Mtb | New TB; died |

| n = 1 | R | R | S | R | R | R | S | S | S | R | S | Mtb | New TB; not evaluated |

| n = 1 | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | Mtb | Retreatment; died |

| n = 1 | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | Mtb | New TB; died |

| n = 1 | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | Mtb | Retreatment; completed (first-line treatment) |

| n = 1 | R | R | S | R | R | S | B | S | S | S | S | Mtb | Retreatment; not evaluated |

| n = 1 | R | R | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | Mtb | Retreatment; died |

| n = 1 | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | S | S | S | S | Mtb | New TB; failure (first-line treatment) |

AM = amikacin; B = borderline; CM = capreomycin; CS = cycloserine; EMB = ethambutol; ETO = ethionamide; INH = isoniazid; Mtb = Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Maf = Mycobacterium africanum; ND = not done; OFX = ofloxacin; PAS = 4-aminosalicylic acid; PZA = pyrazinamide; R = resistant; RIF = rifampicin; S = sensitive; STR = streptomycin; TB = tuberculosis. Sample collection period: June 2012 to October 2013.

Classification of TB patients by case definitions (based on guidelines by WHO for adults9 and on criteria of Graham and others for children10), anatomical site, and history of TB treatment is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Classification of TB patients according to WHO case definitions, anatomical site, and previous TB treatment (n [%])9,10

| Total | Adults | Children | Summary of definition9,10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 201 | N = 170 | N = 31 | ||

| Adults (WHO9) | ||||

| Bacteriologically confirmed | NA | 126 (74.1) | NA | Positive microscopy or culture |

| Clinically diagnosed | NA | 44 (25.9) | NA | Diagnosis by clinician or other medical practitioner |

| Children (Graham and others10) | ||||

| Confirmed TB | NA | NA | 7 (22.6) | Microbiological confirmation |

| Probable TB | NA | NA | 17 (54.8) | Chest X-ray consistent with TB and one of the following: exposure to TB or positive TB treatment response or immunological evidence of TB |

| Possible TB | NA | NA | 5 (16.1) | Chest X-ray consistent with TB or exposure to TB or positive TB treatment response or immunological evidence of TB |

| TB unlikely | NA | NA | 2 (6.5) | Not fitting the above definitions |

| Anatomical site (WHO9) | ||||

| Pulmonary | 190 (94.5) | 161 (94.7) | 29 (93.5) | Involving lung parenchyma or tracheobronchial tree |

| Extrapulmonary* | 9 (4.5) | 9 (5.3) | 0 | Exclusively involving organs other than the lungs |

| Classification based on history of previous TB treatment (WHO9) | ||||

| New TB | 165 (82.1) | 140 (82.4) | 25 (80.6) | No previous TB treatment |

| Previous TB treatment | 30 (14.9) | 24 (14.1) | 6 (19.4) | Previous TB treatment of 1 month or more |

| Relapse | 13 (6.5) | 11 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | Previously declared cured or TB treatment completed |

| Treatment after failure | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.8) | 0 | Most recent TB treatment failed |

| Treatment after LTFU | 11 (5.5) | 8 (4.7) | 3 (9.7) | LTFU at the end of most recent TB treatment |

| Other previously treated patients | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (3.2) | Most recent TB treatment outcome unknown |

| Patients with unknown previous TB history | 6 (3.0) | 6 (3.5) | 0 | Do not fit into any of the categories listed above |

LTFU = lost to follow-up; NA = not available; TB = tuberculosis; WHO = World Health Organization.

For two children data for classification based on anatomical site were not available.

TB treatment and outcomes in adults and children.

Most patients were treated by the health facility where they presented for diagnosis. Of those diagnosed at CERMEL (patients coming directly for TB screening without being referred by any health-care center), most (22/28, 79%) were referred to HAS for treatment and the remainder to CTA, CHRGR, and BELE; five patients received treatment in prison coordinated by BELE. Follow-up data could be obtained for 120/201 (60%) and 80/183 (44%) patients at M2 and M6, respectively; follow-up continued beyond M6 for 48/181 (27%) patients. Follow-up was done via phone call, face to face, or by checking hospital files in 55%, 34%, and 11% of patients, respectively. Treatment outcomes by WHO definitions are presented in Table 5; the overall mortality rate was 10%.

Table 5.

Treatment outcomes according to WHO (n ([%])9

| Total including MDR-TB | Total excluding MDR-TB | Definition9 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Adults | Children | Total | HIV-uninfected | HIV-infected | ||

| N = 201 | N = 170 | N = 31 | N = 193 | N = 108 | N = 67 | ||

| Treatment success | 106 (52.7) | 90 (52.9) | 16 (51.6) | 106 (54.9) | 64 (59.3) | 30 (44.8) | Total of “cured” and “treatment completed” |

| Cured | 15 (7.5) | 13 (7.6) | 2 (6.5) | 15 (7.8) | 10 (9.3) | 4 (6.0) | Smear or culture negative in the last month of treatment and on one previous occasion |

| Treatment completed | 91 (45.3) | 77 (45.3) | 14 (45.2) | 91 (47.2) | 54 (50.0) | 26 (38.8) | No evidence of failure but not meeting criteria for “cured” |

| Treatment failed | 5 (2.5) | 4 (2.4) | 1 (3.2) | 5 (2.6) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (3.0) | Smear or culture positive at month 5 or later |

| Died | 21 (10.4)* | 20 (11.8) | 1 (3.2) | 17 (8.8) | 0 | 17 (25.4) | Death for any reason |

| Lost to follow-up | 34 (16.9) | 26 (15.3) | 8 (25.8) | 34 (17.6) | 21 (19.4) | 12 (17.9) | Treatment interruption for two consecutive months or more |

| Not evaluated | 35 (17.4)† | 30 (17.6) | 5 (16.1) | 31 (16.1) | 20 (18.5) | 6 (9.0) | Treatment outcome unknown |

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; MDR = multidrug resistance; TB = tuberculosis; WHO = World Health Organization.

Including 4 (2.0%) patients with MDR-TB.

Of the patients, 4 (2.0%) with MDR-TB were classified as not evaluated since none of them received appropriate second-line treatment.

For 47/133 (35%) surviving patients for whom the TB drug regimen was precisely documented, the treatment regimen deviated from the Gabonese TB guidelines in terms of treatment interruptions, inadequate drug combinations (following drug stock-outs), imprecise timing of control visits, or incorrect drug dosage. Furthermore, at least seven patients stopped treatment directly after being discharged from the hospital. Of patients classified as treatment success, 30/107 (28%) admitted any interruption of TB treatment with a median duration of 5 (IQR = 2–14) days; treatment interruption or discontinuation occurred after a mean of 1.9 (SD = 1.5) months. Most common reasons reported for treatment interruption or discontinuation were non-affordability of transportation costs (39%) and forgetting drug intake (29%). Further reasons reported in decreasing frequency were subjective recovery, ignorance of the need to continue TB therapy, travel, drug supply disruptions, family problems, side effects, and immobility. Thirteen (9%) patients reported consulting a traditional healer additionally to their standard TB treatment.

At M2 and M6, 52 (58%) and 11 (19%) adult patients, and six (27%) and three (25%) children still had any TB signs and symptom(s), respectively. In adults, remaining symptoms were mostly cough and fatigue, while in children remaining symptoms were mostly cough and fever. Of adult patients, 67 (79%) and 52 (88%) had gained weight at M2 and M6, with a mean of 3.2 (SD = 3.8) and 6.1 (SD = 6.0) kg, respectively, and of children, 18 (86%) and 10 (91%) had gained weight at M2 and M6, respectively.

Sputum was obtained at M2 and M6 from 46 (27%) and 30 (18%) adult patients and six (19%) and three (10%) children. Follow-up sputum smear microscopy was done from three sputa in 75% of cases and from two and one sputa in 12% and 14%, respectively. Of initially smear- or culture-positive patients, 47/134 (35%) and 26/134 (19%) patients provided sputum samples at M2 and M6, respectively, and nine (19%) and two (8%) were still smear- or culture-positive at M2 and M6, respectively. Of seven smear- or culture-positive patients at M6 or later, one patient was an MDR-TB patient, one patient had received an underdosed TB regimen, two had interrupted treatment for more than two months, and for the remainder treatment interruption was not reported but could not be excluded. All smear- or culture-negative patients remained so until end of follow-up. No newly acquired MDR-TB was observed during follow-up; one MDR-TB patient developed additional resistance to PZA within the first month of treatment.

As culture results were not available at treatment initiation, all patients whose cultures showed MDR-TB were treated with oral first-line TB drugs, three of them additionally received STR for two months. Outcomes of MDR-TB patients are presented in Table 3.

Risk factors for unfavorable treatment outcome.

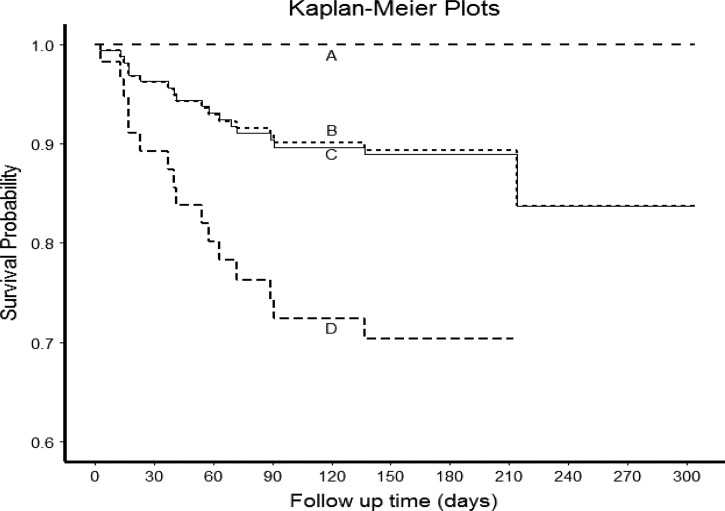

Risk factors for unfavorable treatment outcome were far distance to treatment center (≥ 15 km) (aOR = 3.2, 95% CI = 1.1–9.9, P = 0.04) and clinical (not bacteriologically confirmed) diagnosis of TB (aOR = 2.8, 95% CI = 1.0–7.9, P = 0.04). Risk factors significantly associated with death were HIV infection (aOR = 6.9, 95% CI = 1.6–29.7, P = 0.02) and clinical (not bacteriologically confirmed) diagnosis of TB (aOR = 3.3, 95% CI = 1.1–9.4, P = 0.03) (MDR-TB excluded). Mean (SD) survival time of deceased patients was 53 (50) days after treatment initiation. The only risk factor significantly associated with treatment default was long duration of cough before diagnosis (aOR = 3.6, 95% CI = 1.1–11.1, P = 0.04). Survival analysis is presented in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Survival analysis of tuberculosis (TB) patients in Lambaréné 2012–2013 (survival defined as availability of any information on the patient being alive 5 months after treatment initiation or later). A = Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–uninfected patients excluding multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) (N = 96, deaths N = 0); B = all patients excluding MDR-TB (N = 169, deaths N = 17); C = all patients (N = 174, deaths N = 18); D = HIV-infected patients excluding MDR-TB (N = 59, deaths N = 17). Twenty-seven patients were excluded for survival analysis because the dates of death/loss of follow-up/study end were not available.

Discussion

This is the first prospective cohort study on clinical and microbiological determinants of TB disease from Gabon, a middle-income country in Central Africa ranking among the top 10 countries in terms of TB incidence per population in 2013.1 Overall, this cohort of 201 TB patients comprised 15% children; 38% were HIV co-infected, 75% of patients had bacteriologically confirmed TB, and 82% were new TB cases. Disconcertingly, only half of the patients had a successful treatment outcome, and mortality among patients with HIV coinfection was high (25%). DST showed resistance to any TB drug in 16% of culture-confirmed TB cases; among culture-confirmed retreatment TB cases, 31% had MDR-TB.

The HIV/TB coinfection rate of 38% in patients with known HIV status was 3.5-fold higher than estimated by the WHO in the 2013 country profile (11%),5 higher but closer in line with national reports (26%)11 and reports from retrospective studies evaluating TB patients hospitalized in the capital Libreville (26–32% in 2001–2010) and Lambaréné (34% in 2007–2012),12–15 and similar to a recent report from neighboring Cameroon.16 The true HIV/TB coinfection rate may even be higher, since the HIV status could not be ascertained for almost 10% of patients. Every 10th patient presenting with TB was newly diagnosed with HIV infection, underlining the importance of the current WHO guidelines that every TB patient should be tested for HIV.17

Patients presented late. Of patients with a cough, half were coughing for at least 1 month and a quarter for 3 months or more. Reasons for late presentation in Gabon were suggested to be stigma, costs, and cultural in terms of patients commonly seeking medical help in herbal medicines, at pharmacies, or with traditional healers.15,18 Late presentation and delay in diagnosis of pulmonary TB (PTB) translates into increased transmission in the community, which remains a widespread problem and a major challenge for effective TB control.19 In this study, late presentation was also a risk factor positively correlated with being lost to follow-up. For improved TB control in Gabon, active TB case finding strategies and implementation of directly observed therapy (DOT) need to become a high priority. Of note, every 10th patient sought care for TB in Lambaréné despite other TB treatment centers being closer to their residency.

Weight loss, cough, and fever were the three most common TB symptoms reported. A quarter of patients reported hemoptysis, a rate much higher than reported in a retrospective study from an urban cohort in Gabon.15 In sputum of smear-/culture-negative patients with hemoptysis (5% of patients in this cohort), paragonimiasis, a parasitic infection endemic in Gabon that shares similar clinical manifestations with PTB,20–24 should be considered; however, this was not investigated in the context of this study. In other co-endemic regions, routine exclusion of paragonimiasis has been proposed, as the costs of incorrect diagnosis and treatment may be significant.25

Mycobacterial culture and molecular diagnostic tests are not yet routinely available in Gabon. For this study, cultures were referred overseas, requiring storage and shipment of samples. The culture contamination rate of < 5% was acceptable (and inferior to other reports26,27); and positive cultures in some patients with negative microscopy reflect the expected higher sensitivity of culture compared with microscopy and correlates with the high HIV coinfection rate. Decreased viability following either unreported intake of TB drugs before sampling or sample storage and shipment may however have yielded false negative culture results.

Mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis were isolated in almost a fifth of the patients. Mycobacterium africanum, a subspecies within the M. tuberculosis complex and only endemic in west African countries, had a prevalence of 18% in this Gabonese cohort. Although M. africanum has never been reported in Gabon, in neighboring Cameroon a prevalence of 56% was previously reported using biochemical speciation28 and 9% using molecular methods.29 In our cohort, M. africanum infection was not associated with HIV infection, clinical presentation, or outcome of TB treatment. Resistance pattern must be monitored carefully as 12% of isolates were resistant to INH.

Two-thirds of adult patients had bacteriologically confirmed TB, a rate comparable to a previous retrospective study from Lambaréné13 but higher than reported in the capital Libreville14,15 and in the national report for 2012/2013.11 As the standard of care differs between the central and the regional level, notably with a lack of pulmonologists, diagnosis of smear-negative TB may be more challenging, and accordingly cases may be missed in Lambaréné. Unexpectedly few (< 5%) patients were diagnosed with exclusive EPTB. As in settings with high HIV prevalence, EPTB may account for a considerable part of the total TB burden, and in previous retrospective reports from Gabon, EPTB accounted for 20%/15% and 39%/35% of TB cases in HIV-uninfected and HIV-infected hospitalized patients, respectively.13,15 Underdiagnosis of EPTB in this setting is probable, possibly due to a lack of established diagnostic procedures for EPTB. A recent report from Cameroon found EPTB without concurrent PTB in 35% of inpatients with a similar TB/HIV coinfection rate.16 Point-of-care focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated TB can contribute to improve diagnosis of EPTB in patients with HIV infection in resource-limited settings.30–32

On the basis of a previous anecdotal report on MDR- and XDR-TB,33 unavailability of DST, instable access to first-line TB drugs and inaccessibility of second-line TB drugs,2 as well as low treatment completion rates5 in Gabon, concerns about the prevalence and extent of DR-TB were high. With 4% and 31% of MDR-TB in new and previously treated patients, respectively, the MDR-TB rates exceeded the estimates reported for 2013 by the WHO (3.5% and 20.5%, respectively).1 Among first-line antituberculous drugs, INH and STR showed the highest rates of resistance (13% and 12%). As STR resistance was high among retreatment and MDR-TB patients, the current local guidelines recommending addition of STR to the four oral first-line antituberculous drugs for previously treated TB patients may need revision. For the African WHO region, any INH resistance was reported to be around 6% and 20% among new and retreatment cases, respectively; and in countries with ≥ 2% HIV prevalence, 7.3% of all incident TB cases had INH resistance.34 Importantly, in countries with high HIV prevalence, INH resistance renders isoniazid preventive therapy ineffective and hampers prevention and control of HIV-associated TB. INH resistance and effectiveness of IPT in Gabon should be carefully monitored.

All MDR-TB isolates exhibited further resistances; 7/8 showed additional resistance to EMB and STR, and 4/8 were resistant to PZA. Therefore, for half MDR-TB cases, no first-line antituberculous drugs were left as partner drugs for a second-line treatment regimen. This underlines the urgent need for second-line drugs availability in Gabon. With regard to second-line drugs, 4/8 of the isolates were resistant (or had reduced sensitivity) to ETO and 2/8 isolates showed any second-line drug resistance other than to ETO (PAS and OFX). The high rates of ETO and INH resistance may be related, as both drugs share common pathways, which can lead to cross-resistance.35

Treatment success was worryingly low (53%), and only 8% of patients could be classified as cured according to the WHO guidelines; this is far off from the WHO target treatment success rate of 86% among all new TB cases.1 Given the research framework of this study with designated human and laboratory resources, the true treatment success rate outside of this study setting must be estimated as even lower. Most patients with unsuccessful treatment were lost to follow-up or could not be evaluated due to unknown outcome. Main reasons for treatment interruption reported from Libreville, and in line with our study results, were lack of money to cover related costs and the perception of being cured.36 Patients presenting late had a higher risk for being lost to follow-up, urging that these patients should receive special attention. Possible misdiagnosis of bacteriologically non-confirmed TB cases (e.g., paragonimiasis) may also account for the increased risk of unfavorable treatment outcome in clinically diagnosed TB patients.

Of concern, for at least more than one-third of patients, a deviation from the TB regimens recommended by the national guidelines was documented. DOTS has not been implemented outside the hospital, drug stock-outs occur, and due to decentralized TB treatment care, many different health-care staff without specialized TB training manage TB patients, promoting incorrect TB treatment prescriptions.2 On the other hand, patient-centered reasons are prevalent as well; such as economic barriers and lack in health education and different perceptions of disease and TB, leading to competing health-care seeking behavior toward traditional healers.18 Although health-care system deficiencies may be easier to address, improving patient's awareness and understanding of TB and its successful management will be more challenging.

In this cohort, the most important risk factor for death was HIV coinfection. Mortality rates in Gabon clearly exceed the global and regional mortality rates and were higher than the mortality rate of 5% previously reported by retrospective analyses from Gabon.13 The active follow-up strategy applied in this cohort may account for a more detailed classification of treatment outcome.

Commonly, adult and pediatric TB patients are not considered within the same cohort, as many aspects around TB differ between adults and children. This study, however, chose a comprehensive approach to gain a cross-sectional insight into all services that care for TB patients in the region. The proportion of 15% of childhood TB in this cohort (especially given the cutoff of < 18 years for childhood TB) may under-represent the true burden in the pediatric population. The proportion of 4% of pediatric TB cases officially notified in Gabon5 certainly reflects significant under-recognition and/or reporting of childhood TB.

This study has some limitations. Because of the observational character and the responsibility of care being with various health-care staff, data collection and documentation was sometimes incomplete. On the other hand, the observational design of the study is more likely to reflect the true situation in the field. However, human and laboratory resources provided through the study may also have influenced the observations in terms of completeness of TB diagnostics and higher follow-up rates. An explicit limitation is the incompleteness of data on antiretroviral treatment.

This study has several strengths. By enrolling patients from different health-care facilities that care for TB patients, coverage of TB care in this area was comprehensively approached. Several different mycobacterial diagnostic tests were used to increase sensitivity; by shipping samples to the German reference laboratory DST was performed according to the highest standards. Although the catchment area of this study was broad, generalizability of the findings to the rest of the country or even region must be made cautiously.

A recent grant allocation by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria for the period 2016–2018 should enable Gabon's National TB Program to intensify the fight against TB in the country, and more particularly to address the pressing challenge of MDR-TB. This shall notably include roll out of new rapid diagnostic tools (Xpert MTB/RIF, line probe assay) at the central and peripheral levels to facilitate diagnosis in vulnerable populations (children, HIV patients, retreatment failures, contacts of MDR-TB index cases, and prisoners). After the signature of a Memorandum of Understanding with the Gabonese National TB Program, the TB laboratory facility set up by CERMEL in the scope of this study has already been designated as focal site for TB and MDR-TB diagnosis for Moyen Ogooué and neighboring provinces. Furthermore, with the financial assistance of the German government (Federal Ministry of Education and Research) and Damien Foundation, second-line TB drugs have now been made available in country, which should allow the treatment of MDR-TB patients diagnosed thus far.

Conclusions

Despite its ranking among the top 10 high TB incidence countries, Gabon had so far failed to attract international attention or financial assistance to tackle this epidemic and is now faced with emergence and possible dissemination of MDR-TB cases, which represents a major public health threat on both local and global scales. This first study on basic TB epidemiology in Gabon illustrates that TB still represents a deadly infection in some parts of the world, despite the overall global progress in TB control over the past years. In this specific study area, the TB burden is determined by an unacceptably low rate of treatment success, a high rate of HIV coinfection, and the uncontrolled emergence of MDR-TB. The situation highlights the critical need for improving access to TB care as well as the establishment of DOTS, reinforcing in-country diagnostic capacity at all levels of the health-care system, and urgently providing access to second-line drugs for MDR-TB patients. Death of every fourth TB/HIV coinfected patient calls for improvement of integrated TB and HIV care, with special attention to INH resistance prevalence, which may impair prevention of HIV-associated TB. National and international recognition of neglected ongoing hot spots of the TB epidemic is a prerequisite for improving local health and for a globally successful effort to achieve the goal set for the post-2015 global TB strategy.1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all patients who participated in this study and to all health care and laboratory staff who contributed to the performance of this project.

Footnotes

Financial support: The study was supported by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) through a grant to the Pan-African Consortium for the Evaluation of Antituberculosis Antibiotics (PanACEA) Consortium.

Authors' addresses: Sabine Bélard, Department of Pediatric Pneumology and Immunology, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany, E-mail: sabinebelard@yahoo.de. Jonathan Remppis, Davy U. Kombila, Kara K. Osbak, Régis M. Obiang Mba, Harry M. Kaba, Emmanuel B. Bache, Arnaud Flamen, Ayôla A. Adegnika, Bertrand Lell, Marguerite M. Loembé, and Abraham S. Alabi, Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné, Hôpital Albert Schweitzer, Lambaréné, Gabon, E-mails: jonathan.remppis@posteo.de, ukombila@gmail.com, kosbak@hotmail.com, obianregi@yahoo.fr, kharry3@yahoo.fr, bebache@gmail.com, arnaud.flamen@live.fr, aadegnika@gmail.com, bertrand.lell@gmail.com, mmassingaloembe@lambarene.org, and aalabi02@yahoo.co.uk. Sanne Bootsma, Saskia Janssen, and Martin P. Grobusch, Center of Tropical Medicine and Travel Medicine, Department of Infectious Diseases, Division of Internal Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, E-mails: bootsmasanne@gmail.com, s.janssen@amc.uva.nl, and m.p.grobusch@amc.uva.nl. Justin O. Beyeme and Cosme Kokou, Hôpital Albert Schweitzer de Lambaréné, Lambaréné, Gabon, E-mails: justinomva@yahoo.fr and ckokou2002@yahoo.fr. Elie G. Rossatanga, Centre de Traitement Ambulatoire Lambaréné, Lambaréné, Gabon, E-mail: rossatanga@yahoo.fr. Afsatou N. Traoré, Microbiology Department, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa, E-mail: traoresafi@hotmail.com. Jonas Ehrhardt, Matthias Frank, and Peter G. Kremsner, Institut für Tropenmedizin, Universitätsklinikum Tübingen, Eberhard Karls Universität, Tübingen, Germany, E-mails: jonasehrhardt@yahoo.de, matthias.frank@medizin.uni-tuebingen.de, and peter.kremsner@uni-tuebingen.de. Sabine Rüsch-Gerdes and Stefan Niemann, National Reference Center for Mycobacteria, Forschungszentrum Borstel, Borstel, Germany, E-mails: srueschg@t-online.de and stniemann@yahoo.de.

References

- 1.WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2014. 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/137094/1/9789241564809_eng.pdf?ua=1 Available at. Accessed August 5, 2015.

- 2.Bélard S, Janssen S, Osbak KK, Adegnika AA, Ondounda M, Grobusch MP. Limited access to drugs for resistant tuberculosis: a call to action. J Public Health (Oxf) 2014;37:691–693. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janssen S, Huson MA, Belard S, Stolp S, Kapata N, Bates M, van Vugt M, Grobusch MP. TB and HIV in the Central African region: current knowledge and knowledge gaps. Infection. 2014;42:281–294. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0568-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Direction Générale de la Statistique (DGS) du Gabon et ICF International . Enquête Démographique et de Santé du Gabon 2012: Rapport de synthèse. Calverton, MD: DGS et ICF International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Tuberculosis Country Profile Gabon. 2013. https://extranet.who.int/sree/Reports?op=Replet&name=%2FWHO_HQ_Reports%2FG2%2FPROD%2FEXT%2FTBCountryProfile&ISO2=GA&LAN=EN&outtype=html Available at. Accessed May 18, 2015.

- 6.Ramharter M, Adegnika AA, Agnandji ST, Matsiegui PB, Grobusch MP, Winkler S, Graninger W, Krishna S, Yazdanbakhsh M, Mordmüller B, Lell B, Missinou MA, Mavoungou E, Issifou S, Kremsner PG. History and perspectives of medical research at the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambarene, Gabon. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119((19–20 Suppl 3)):8–12. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0857-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministre de la Santé, des Affaires Sociales, de la Solidarité et de la Famille . Guide Technique National. 4th edition. Gabon: Programme National de Lutte Contre la Tuberculose; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD) Sputum Examination for Tuberculosis by Direct Microscopy in Low Income Countries—Technical Guide. 5th edition. 2000. http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/bugdrug/antibiotic_manual/IUATLD_afb%20microscopy_guide.pdf Available at. Accessed August 5, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Definitions and Reporting Framework for Tuberculosis—2013 Revision. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/79199/1/9789241505345_eng.pdf Available at. Accessed August 5, 2015. [PubMed]

- 10.Graham SM, Ahmed T, Amanullah F, Browning R, Cardenas V, Casenghi M, Cuevas LE, Gale M, Gie RP, Grzemska M, Handelsman E, Hatherill M, Hesseling AC, Jean-Philippe P, Kampmann B, Kabra SK, Lienhardt C, Lighter-Fisher J, Madhi S, Makhene M, Marais BJ, McNeeley DF, Menzies H, Mitchell C, Modi S, Mofenson L, Musoke P, Nachman S, Powell C, Rigaud M, Rouzier V, Starke JR, Swaminathan S, Wingfield C. Evaluation of tuberculosis diagnostics in children: 1. Proposed clinical case definitions for classification of intrathoracic tuberculosis disease. Consensus from an expert panel. J Infect Dis. 2012;205((Suppl 2)):S199–S208. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Programme National de Lutte contre la Tuberculose (PNLT) Profil Epidemiologique de la Tuberculose au Gabon 2003—2013. Libreville, Gabon: Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévoyance Sociale; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nkoghe D, Toung Mve M, Nnegue S, Okome Nkoume M, Iba BJ, Hypolite J, Leonard P, Kendjo E. HIV seroprevalence among tuberculosis patients in Nkembo Hospital, Libreville, Gabon. Short note [in French] Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2005;98:121–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stolp SM, Huson MA, Janssen S, Beyeme JO, Grobusch MP. Tuberculosis patients hospitalized in the Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Lambarene, Gabon—a retrospective observational study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:E499–E501. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kombila DU, Moussavou-Kombila JB, Grobusch MP, Lell B. Clinical and laboratory features of tuberculosis within a hospital population in Libreville, Gabon. Infection. 2013;41:737–739. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ondounda M, Ilozue C, Mounguengui D, Magne C, Nzenze JR. Clinical and radiological features of tuberculosis during HIV infection in Libreville, Gabon [in French] Med Trop (Mars) 2011;71:253–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agbor AA, Bigna JJ, Plottel CS, Billong SC, Tejiokem MC, Ekali GL, Noubiap JJ, Toby R, Abessolo H, Koulla-Shiro S. Characteristics of patients co-infected with HIV at the time of inpatient tuberculosis treatment initiation in Yaounde, Cameroon: a tertiary care hospital-based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health. 2015;73:24. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0075-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . Treatment of Tuberculosis Guidelines. 4th edition. 2010. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44165/1/9789241547833_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 Available at. Accessed July 14, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cremers AL, Janssen S, Huson MA, Bikene G, Bélard S, Gerrets RPM, Grobusch MP. Perceptions, health seeking behaviour and implementation of a tuberculosis control programme in Lambaréné, Gabon. Public Health Action. 2013;3:328–332. doi: 10.5588/pha.13.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sreeramareddy CT, Qin ZZ, Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Pai M. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:255–266. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malvy D, Ezzedine KH, Receveur MC, Pistone T, Mercie P, Longy-Boursier M. Extra-pulmonary paragonimiasis with unusual arthritis and cutaneous features among a tourist returning from Gabon. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2006;4:340–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petavy AF, Cambon M, Demeocq F, Dechelotte P. A Gabonese case of paragonimiasis in a child [in French] Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1981;74:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sachs R, Kern P, Voelker J. Paragonimus uterobilateralis as the cause of 3 cases of human paragonimiasis in Gabon [in French] Tropenmed Parasitol. 1983;34:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voelker J, Sachs R. Morphology of the lung fluke Paragonimus uterobilateralis occurring in Gabon, west Africa. Trop Med Parasitol. 1985;36:210–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vuong PN, Bayssade-Dufour C, Mabika B, Ogoula-Gerbeix S, Kombila M. Paragonimus westermani pulmonary distomatosis in Gabon. First case [in French] Presse Med. 1996;25:1084–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belizario V, Jr, Totanes FI, Asuncion CA, De Leon W, Jorge M, Ang C, Naig JR. Integrated surveillance of pulmonary tuberculosis and paragonimiasis in Zamboanga del Norte, the Philippines. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108:95–102. doi: 10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musau S, McCarthy K, Okumu A, Shinnick T, Wandiga S, Williamson J, Cain K. Experience in implementing a quality management system in a tuberculosis laboratory, Kisumu, Kenya. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:693–695. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathewos B, Kebede N, Kassa T, Mihret A, Getahun M. Characterization of Mycobacterium isolates from pulmonary tuberculosis suspected cases visiting Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory at Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute, Addis Ababa Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015;8:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60184-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huet M, Rist N, Boube G, Potier D. Bacteriological study of tuberculosis in Cameroon [in French] Rev Tuberc Pneumol (Paris) 1971;35:413–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niobe-Eyangoh SN, Kuaban C, Sorlin P, Cunin P, Thonnon J, Sola C, Rastogi N, Vincent V, Gutierrez MC. Genetic biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Cameroon. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2547–2553. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2547-2553.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heller T, Goblirsch S, Bahlas S, Ahmed M, Giordani MT, Wallrauch C, Brunetti E. Diagnostic value of FASH ultrasound and chest X-ray in HIV-co-infected patients with abdominal tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:342–344. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heller T, Wallrauch C, Goblirsch S, Brunetti E. Focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated tuberculosis (FASH): a short protocol and a pictorial review. Crit Ultrasound J. 2012;4:21. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssen S, Grobusch MP, Heller T. ‘Remote FASH’ tele-sonography—a novel tool to assist diagnosing HIV-associated extrapulmonary tuberculosis in remote areas. Acta Trop. 2013;127:53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mounguengui D, Ondounda M, Mandji Lawson JM, Fabre M, Gaudong L, Mangouka L, Magne C, Nzenze JR, L'her P. Multi-resistant tuberculosis at the Hâopital d'instruction des Armées de Libreville (Gabon) about 16 cases [in French] Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2012;105:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s13149-011-0195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, Royce S, Madhukar P, Burman W, Vernon A, Lienhardt C. Standardized treatment of active tuberculosis in patients with previous treatment and/or with mono-resistance to isoniazid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machado D, Perdigao J, Ramos J, Couto I, Portugal I, Ritter C, Boettger EC, Viveiros M. High-level resistance to isoniazid and ethionamide in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis of the Lisboa family is associated with inhA double mutations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1728–1732. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mve MT, Bisvigou U, Barry NC, Ondo CE, Nkoghe D. Reasons for stopping and restarting tuberculosis treatment in Libreville (Gabon) [in French] Sante. 2010;20:31–34. doi: 10.1684/san.2010.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]