Abstract

Phase I and II enzymes are involved in the metabolism of endogenous reactive compounds as well as xenobiotics, including toxicants and drugs. Genotyping studies have established several drug metabolizing enzymes as markers for risk of drug hypersensitivity. However, other candidates are emerging that are involved in drug metabolism but also in the generation of danger or costimulatory signals. Enzymes such as aldo-keto reductases (AKR) and glutathione transferases (GST) metabolize prostaglandins and reactive aldehydes with proinflammatory activity, as well as drugs and/or their reactive metabolites. In addition, their metabolic activity can have important consequences for the cellular redox status, and impacts the inflammatory response as well as the balance of inflammatory mediators, which can modulate epigenetic factors and cooperate or interfere with drug-adduct formation. These enzymes are, in turn, targets for covalent modification and regulation by oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators, and drugs. Therefore, they constitute a platform for a complex set of interactions involving drug metabolism, protein haptenation, modulation of the inflammatory response, and/or generation of danger signals with implications in drug hypersensitivity reactions. Moreover, increasing evidence supports their involvement in allergic processes. Here, we will focus on GSTP1-1 and aldose reductase (AKR1B1) and provide a perspective for their involvement in drug hypersensitivity.

Keywords: glutathione transferase, aldose reductase, inflammation, oxidative stress, detoxification, allergy, drug adduct, drug hypersensitivity

Introduction

Drug hypersensitivity reactions pose an important clinical problem. They reduce the therapeutic armamentarium and may entail great severity, being life threatening in some cases. These reactions are mediated by the activation of the immune system by drugs or their metabolites. This can occur through the direct interaction of the drug/metabolite with receptors from immune cells or by covalent attachment of the drug to endogenous proteins, in a process known as haptenation. It is often considered that drugs are too small structures to activate the immune system on their own, whereas haptenated proteins or peptides can fulfill this role and be processed and presented by antigen presenting cells. In addition, factors leading to the exacerbation of the inflammatory response, the generation of danger signals or oxidative stress, contribute to the development of hypersensitivity reactions through mechanisms not completely understood.

Detoxifying and metabolic enzymes play multiple roles in cell homeostasis and may participate in drug hypersensitivity through various mechanisms. Metabolites produced by drug transformation carried out by these enzymes could activate the immune system. In addition, detoxifying enzymes play important roles in the control of inflammation, cellular redox status, and cytotoxicity.

Inflammation and oxidative stress cooperate in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases. A situation of oxidative stress may concur with sensitization and favor Th2 responses (Utsch et al., 2015). Moreover, oxidative stress induction is common to chemical allergens, including those that induce type IV hypersensitivity (Corsini et al., 2013). Indeed, numerous drugs, including doxorubicin, dapsone, cisplatin, sulfamethoxazole, and many others, elicit oxidative stress through multiple mechanisms (Bhaiya et al., 2006; Deavall et al., 2012; Hargreaves et al., 2016), increasing the generation of danger signals that act as coactivators for the allergic reaction (Sanderson et al., 2006). In turn, oxidative stress can increase the formation of drug-protein adducts by favoring the generation of reactive metabolites of drugs, thus facilitating protein haptenation and subsequent activation of the immune system or other toxic effects. Furthermore, oxidized proteins may be more susceptible to the addition of certain drugs or drug metabolites (Lavergne et al., 2009). Oxidative stress can also alter the ratio between reduced and oxidized glutathione species by depletion of the reduced form (GSH), thus favoring protein glutathionylation and/or reducing the possibility of drug detoxification through GSH conjugation. Conversely, it has been reported that antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine, ebselen, and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate can ameliorate immune and allergic responses in several models (Matsue et al., 2003; Monick et al., 2003; Galbiati et al., 2011). Importantly, a reduced antioxidant or cytoprotective capacity has been evidenced in allergy and asthma (Lutter et al., 2015), and sensitization to certain allergens is associated with inadequate antioxidant responses. Consequently, it has been proposed that exploring the master regulator of antioxidant responses Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2), may provide novel biomarkers for determining the sensitization potential of several chemicals (Natsch and Emter, 2008; Ade et al., 2009).

Recently, we have studied two types of detoxifying enzymes, GST and AKR (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2007, 2010; Díez-Dacal et al., 2016), which interact with several drugs and are important players in the regulation of inflammation and redox status. Indeed, genetic variations in these enzymes have been associated with an increased risk of suffering diseases with an important allergic component such as atopy or asthma. Nevertheless, whereas the role of other drug metabolizing enzymes, such as cytochromes, in drug hypersensitivity has been frequently explored (Gueant et al., 2008; Bhattacharyya et al., 2014), those of GST and AKR remain poorly understood. Here, we provide a perspective on the interactions of GSTP1-1 and AKR1B1 with both drugs and factors contributing to allergic reactions, and suggest avenues to assess their potential as drug hypersensitivity biomarkers.

GSTP1-1

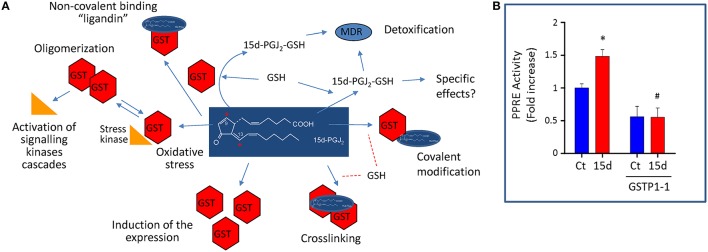

Glutathione-S-transferases are phase II enzymes that detoxify numerous endogenous and exogenous compounds by conjugation with GSH (Hayes et al., 2005). GSH-conjugates can then be exported from cells by the multidrug transporter system (Díez-Dacal and Pérez-Sala, 2012). Numerous genetic variations in GST enzymes have been identified and their functional consequences have been the subject of previous review (Board and Menon, 2013). Regarding GSTP1-1, the polymorphisms described have been mostly studied in the context of cancer and drug metabolism. However, in addition to its metabolic function, GSTP1-1 modulates stress response cascades by mechanisms involving protein-protein interactions with signaling proteins, like c-Jun terminal Kinase (JNK) and other mitogen activated protein kinases, Peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6), and Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-associated factor 2 (TRAF2; Adler et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2006). Moreover, GSTP1-1 facilitates protein glutathionylation, thus regulating protein activity (Tew, 2007). Therefore, a complex landscape appears in which GSTP1-1 integrates cellular responses to redox stress by catalytic, protein-protein interaction and posttranslational mechanisms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interactions of GSTP1-1 with the cyPG 15d-PGJ2 as a model of an electrophilic compound that can act both as a substrate and an inhibitor of the enzyme. (A) GSTP1-1 (depicted as “GST” in the scheme) can detoxify electrophilic mediators, like 15d-PGJ2, and drugs, by conjugating them with GSH or through its ligandin role. In turn, GSTP1-1 can be covalently modified and/or cross linked by these compounds. Crosslinking or oligomerization secondary to drug-induced oxidative stress can impact stress signaling cascades. In addition, electrophilic drugs or mediators can induce GSTP1-1 expression in a cell-type dependent manner. (B) The ability of GSTP1-1 to detoxify and reduce the effects of 15d-PGJ2 is illustrated: GSTP1-1 overexpression blocks the activity of a PPAR promoter reporter element (PPRE) in cells. Rat mesangial cells were transfected with PPRE as previously described (Zorrilla et al., 2010), and with a GSTP1-1 expression vector where indicated. Then cells were treated in the absence (Ct) or presence of 15d-PGJ2 (15d) and the promoter activity measured by luminescence. The overexpression of GSTP1-1 was sufficient to block PPAR activation induced by the prostaglandin. *p > 0.05 vs. Ct, #p < 0.05 vs. 15d-PGJ2. Values represent mean ± SEM from three different experiments.

Interaction of GSTP1-1 with oxidative stress

GSTP1-1 is a key factor for cellular adaptation to oxidative stress at multiple levels. GSTP1-1 expression is strongly induced by oxidative stress as a defense mechanism through the binding of transcription factors, like Nrf-2 and activator protein (AP)-1, to the antioxidant response elements in its promoter (Kawamoto et al., 2000; Hayes et al., 2005). In turn, oxidative stress can reversibly inactivate GSTP1-1 by intramolecular disulfide formation or oligomerization (Shen et al., 1993; Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2010). Moreover, several electrophilic agents, including endogenous reactive mediators and drugs, induce an irreversible crosslinking of the enzyme (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2013). The main residues involved in these modifications are the most reactive cysteines in GSTP1-1, namely, Cys47, and/or Cys101. Both, GSTP1-1 oligomerization and crosslinking affect its interactions with signaling proteins and stress cascades, as mentioned above.

GSTP1-1 can promote the reversible incorporation of GSH (S-glutathionylation) into low pKa cysteine residues of proteins. This modification modulates protein function, but also protects cysteine residues from further irreversible oxidations (Tew, 2007; Townsend et al., 2009), allowing the reduced form to be regenerated. Proteins S-glutathionylated by GSTP1-1 include Prdx6 (Manevich and Fisher, 2005), AKR1B1, and GSTP1-1 itself (Townsend et al., 2009; Wetzelberger et al., 2010).

Altogether, this evidence illustrates the complex redox regulation of GSTP1-1. Under mild oxidative stress, induction of GSTP1-1 expression and its redox “recycling” function afford cellular protection. However, pharmacological treatments or acute inflammation can inactivate GSTP1-1 either by direct oxidation and/or chemical inhibition. In both cases, allelic variants of GSTP1-1, namely, wild type GSTP1-1 (Ile105, Ala114) and variants: GSTP1-1(Ile105Val, Ala114), GSTP1-1(Ile105Val, Ala114Val), and GSTP1-1(Ile105, Ala114Val), differentially exert protective functions on protein activity and lipid peroxidation, which may influence susceptibility to oxidative stress of subjects carrying the various forms (Manevich et al., 2013).

Interaction of GSTP1-1 with drugs

GSTP1-1 displays multiple interactions with drugs, either catalyzing their detoxification by GSH conjugation or being inactivated by them. These interactions are crucial for cancer therapy. GSTP1-1 overexpression is an important factor involved in tumor chemoresistance (Díez-Dacal and Pérez-Sala, 2012), and therefore, an important drug target, for which structurally diverse inhibitors, including ethacrynic acid, glutathione analogs, GSTP1-1 activatable drugs, and natural compounds have been considered (Singh, 2015). The mechanism of action of these compounds frequently involves binding to cysteine residues and/or GSTP1-1 oligomerization, as it occurs with electrophilic prostaglandins (PGs) or chlorambucil (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2013). Interestingly, the pattern of GSTP1-1 crosslinking and/or chemical modifications depends on the presence of both substrates and inhibitors, for which this enzyme can be considered a converging platform for the effects of drugs and danger signals arising from oxidative stress or inflammation (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2013).

GSTP1-1 also keeps important direct or indirect interactions with the mechanism of action of drugs such as acetaminophen (McGarry et al., 2015), acetylsalycilic acid (Baranczyk-Kuzma and Sawicki, 1997), and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Orhan and Sahin, 2001). In fact, GSTP1-1 deficiency correlates with higher acetaminophen toxicity in mice (McGarry et al., 2015). Also, a “ligandin” role of GSTP1-1 should be taken into account, since this abundant cytosolic enzyme can sequester drugs, thus reducing their effective concentrations (Oakley et al., 1999; Lu and Atkins, 2004).

Interaction of GSTP1-1 with inflammatory mediators

GSTP1-1 also displays multiple interactions with inflammation: it is induced by proinflammatory stimuli, but this could exert a negative feedback on the inflammatory response. GSTP1-1 ameliorates the inflammatory response in several experimental models of tissue damage or inflammation (Xue et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2009). Interestingly, several GST, including GSTP1-1, attenuate the action of the inflammatory mediator 15-deoxy-Δ12, 14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2; Paumi et al., 2004). Evidence from our laboratory indicates that overexpression of GSTP1-1 in rat mesangial cells reduces the capacity of 15d-PGJ2 to activate Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) transcription factor(s) (Figure 1). Moreover, a reduction in the basal PPAR activity is also observed, suggesting the inactivation of endogenous PPAR agonists or the participation of additional mechanisms in GSTP1-1 regulation of inflammation.

In turn, electrophilic mediators like 15d-PGJ2 can inhibit GST activity in several cell types through various mechanisms (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2007). Interestingly, cyclopentenone prostaglandins (cyPG) with dienone structure induce an extensive intermolecular crosslinking of GSTP1-1 monomers, involving mainly Cys47 and Cys101 (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2013) that is blocked by GSH or non-metabolizable GSH analogs, indicating that cyPG-GSTP1-1 interaction is impaired in the GSH-bound enzyme.

Therefore, the interaction of GSTP1-1 with inflammatory mediators like cyPG is a two-way process strongly dependent on GSH availability (Gayarre et al., 2005; Díez-Dacal and Pérez-Sala, 2010), since the enzyme can conjugate electrophilic mediators with GSH, whereas cyPG can induce the expression and/or inhibit GST activity in a cell type-dependent manner (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2007). Some of these interactions have also been evidenced for other GST isoforms (Gilot et al., 2002; Kudoh et al., 2014). These observations illustrate the intricate implications of GST in inflammation, with the net outcome depending on the delicate balance of all these factors.

GSTP1-1 in allergic reactions

Although GST have been mostly studied in the fields of oxidative stress and chemoresistance, an interesting role in allergic reactions is emerging. Endogenous GSTP1-1 is an important target for haptenation, which has been related to the induction of certain drug hypersensitivity reactions (Meng et al., 2014). In addition, genetic variants of several GST isoforms have been found to associate with allergic processes including asthma (Tamer et al., 2004), drug eruptions (Ates et al., 2004), sensitization to thimerosal (Westphal et al., 2000), or allergic rhinitis (Iorio et al., 2014). In the case of GSTP1-1, both down- and up-regulations of GSTP1-1 levels have been reported in association with asthma (Schroer et al., 2011): whereas low levels could contribute to asthma, oxidative stress associated with the allergic response could induce GSTP1-1 expression. These changes in expression may in turn be modulated by the occurrence of polymorphisms, like Ile105Val (rs 1695; Dragovic et al., 2014), since this variant has been reported to display a reduced ability to conjugate several electrophilic drugs and reactive metabolites to GSH, and may associate with certain allergic diseases, including atopy and asthma (Hoskins et al., 2013). Polymorphic forms of GSTP1-1 correlate with the aggravation of asthma symptoms induced by air pollution (Su et al., 2013), and increased risk of asthma associated with acetaminophen (Kang et al., 2013) and exercise (Islam et al., 2009). In addition, the Ile105 wild type enzyme associates with enhancement of certain nasal allergic responses (Gilliland et al., 2004), whereas, according to another study, the Ala114 wild type enzyme associates with increased risk of atopy (Schultz et al., 2010). Nevertheless, lack of association of GSTP1-1 polymorphisms with allergic diseases or drug hypersensitivity has been reported in other studies, potentially due to differences in the genetic backgrounds of the patient cohorts studied.

Altogether, these findings support the role of GSTP1-1 as a risk factor in hypersensitivity responses by multiple mechanisms, given its multifunctional involvement in drug metabolism and inflammation. Moreover, GSTP1-1 emerges as a key factor to be considered in future genomic studies related with allergy development and drug hypersensitivity reactions.

AKR1B1

AKR1B1 (or aldose reductase) is a member of the AKR superfamily, which comprises multiple enzymes involved in oxidoreduction of endogenous and exogenous compounds, including aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes, monosaccharides, steroids, aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), or isoflavonoids, using NADH or NADPH as cofactors. Structurally, this phase I metabolizing enzyme (Penning and Drury, 2007) is folded into a (α/β)8-barrel motif that is highly conserved among the members of this family and harbors the active site at its C-terminal end (Jez et al., 1997).

AKR1B1 primary role is to afford constitutive and inducible protection against toxic aldehydes generated under oxidative stress (Jin and Penning, 2007; Lyon et al., 2013). AKR1B1 reduces highly reactive lipid peroxidation products like 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE), acrolein, and methylglyoxal, as well as GSH-conjugates of these aldehydes such as glutathionyl-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (GS-HNE) and GS-acrolein (Kolb et al., 1994; Srivastava et al., 1998; Vander Jagt et al., 2001). For instance, AKR1B1 activation played a cardioprotective role in rat myocardial ischemia by decreasing the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products in the ischemic heart (Kaiserova et al., 2008). Similarly, induction of AKR1B1 expression in response to oxidative stress plays a role in the antioxidant response (Wang et al., 2012). AKR1B1 also participates in steroid hormones catabolism and plays an important role in the regulation of steroid function in several tissues (Barski et al., 2008).

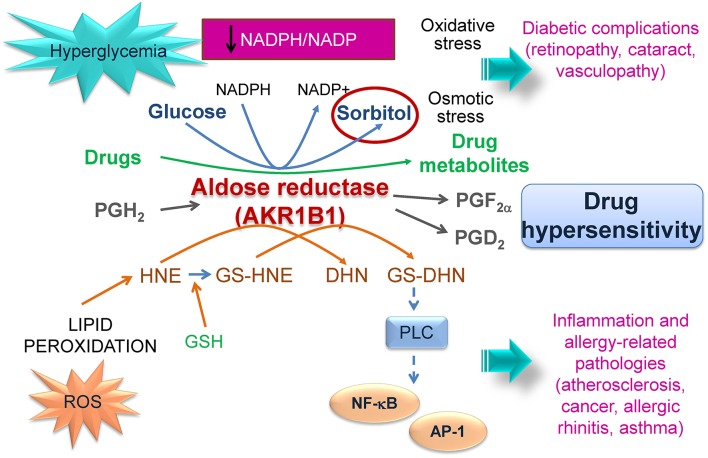

Nevertheless, AKR1B1 also has a negative side since it can promote tumor chemoresistance and contribute to the perpetuation of inflammation and to the development of secondary diabetic complications (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Involvement of AKR1B1 in pathophysiology. AKR1B1 catalyzes the first step in the polyol pathway transforming glucose into sorbitol using NADPH as cofactor. Under hyperglycemic conditions increased sorbitol and NADPH consumption lead to osmotic and oxidative stress, respectively, that can contribute to diabetic complications. AKR1B1 metabolizes drugs leading to inactivation and chemoresistance and/or to the generation of toxic metabolites. In addition, AKR1B1 can metabolize PGH2 yielding PGF2α, which may regulate PGE2 production. Transformation of reactive aldehydes or their GSH-conjugates by AKR1B1 can generate species that perpetuate inflammation and may be involved in allergic responses. The interactions of AKR1B1 with drug metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation an allergic reactions support its consideration in studies of drug hypersensitivity.

Interactions of AKR1B1 with oxidative stress

AKR1B1 activity is regulated by oxidative posttranslational modifications. The highly nucleophilic Cys298, located near the active site, can be modified by different reactive species like nitric oxide (NO), HNE, or oxidized glutathione. These modifications may reduce or increase AKR1B1 catalytic activity, depending on the modifying moiety, and reduce its susceptibility to pharmacological inhibitors. Interestingly, NADPH protects Cys298 from modification by these agents (Chandra et al., 1997; Del Corso et al., 1998; Petrash, 2004).

AKR1B1 is a target gene of Nrf-2, the master transcription factor regulating the antioxidant response. Therefore, it is induced by numerous oxidative stimuli and participates in the antioxidant response (Kang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012). In consequence, AKR1B1 expression is increased in tissues with elevated oxidative stress, e.g., in alcoholic liver disease or vascular inflammation (Srivastava et al., 2005), where in some cases affords a protective role (Kang et al., 2014). Nevertheless, excessive AKR1B1 activity can lead to NADPH depletion and oxidative stress.

This occurs in diabetes, where AKR1B1 metabolizes excess glucose through the polyol pathway. An increased flux through this pathway can lead to osmotic stress due to the increased formation of sorbitol, as well as to a redox imbalance by the elevated consumption of NADPH (Petrash, 2004; Figure 2). NADPH is a substrate/cofactor for several enzymes involved in the cellular antioxidant defense, including glutathione reductase (GSH regeneration), peroxiredoxins and thioredoxin, as well as for several detoxifying systems (Pollak et al., 2007a). Therefore, depletion of NADPH changes the NADPH/NADP+ ratio contributing to oxidative stress and reducing the cellular ability to recover after an oxidative insult (Pollak et al., 2007b; Ying, 2008).

Interaction of AKR1B1 with drugs

AKR1B1 is an important drug target due to its implication in the development of diabetic complications. Therefore, the search for inhibitors from both synthetic and natural sources has yielded a wide array of compounds that bind and/or inhibit the enzyme, with structural information on their binding arising from molecular modeling or crystallographic studies. AKR enzymes are involved in chemoresistance because they metabolize carbonyl-containing drugs, including naloxone and ketotifen (Endo et al., 2014). The anthracycline antibiotics doxorubicin and daunorubicin pose an important case, since they are among the most effective chemotherapic drugs. However, the reduction of their carbonyl group to their corresponding alcohol, yielding doxorubicinol and daunorubicinol, respectively, reduces their efficacy (Veitch et al., 2009). Overexpression of AKR1B1 inactivates these drugs and leads to resistance of various tumor cells (Plebuch et al., 2007; Heibein et al., 2012). Conversely, AKR1B1 inhibition increases the cytotoxic effects of the anticancer agents doxorubicin and cisplatin in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells (Lee et al., 2002), and the AKR inhibitors PGA1 and AD-5467 improve the effectiveness of doxorubicin in lung cancer cells (Díez-Dacal et al., 2011; Díez-Dacal and Pérez-Sala, 2012). Natural variants of certain AKR enzymes have been identified that present a reduced capacity to metabolize daunorubicin and doxorubicin in vitro (Bains et al., 2008, 2010). There is little information on the involvement of AKR1B1 metabolites in hypersensitivity reactions. Nevertheless, daunorubicinol has toxic effects per se because it induces cardiomyopathy (Minotti et al., 2004).

Interaction of AKR1B1 with inflammatory mediators

AKR1B1 plays an important role in different inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis, sepsis, asthma, uveitis, and colon cancer. AKR1B1 can be induced by proinflammatory stimuli (Bresson et al., 2012). Transcription factors Nuclear factor (NF)-κB and AP-1 activate the AKR1B1 promoter through binding to the osmotic response element (ORE; Iwata et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2005) and the phorbol ester response or AP-1 sites, respectively (Penning and Drury, 2007).

Although AKR1B1 can play a protective role by detoxifying acrolein or HNE, it can also play a positive/amplifying role in inflammation through various mechanisms (Figure 2). In particular, metabolism of HNE or its glutathione conjugate GS-HNE can result in products, such as 1, 4-dihydroxynonene (DHN) and glutathionyl-1,4-dihydroxynonane (GS-DHN), which are still toxic and promote activation of phospholipase C (PLC)-NF-κB cascades perpetuating inflammation (Ramana et al., 2006; Srivastava et al., 2011). Thus, inhibition of AKR1B1 reduced NF-κB-dependent inflammatory markers, and the synthesis of TNF-α stimulated by hyperglycemic conditions, and of inflammatory mediators like NO and PGE2 (Ramana and Srivastava, 2010).

Interestingly, AKR1B1 displays PGF2α synthetizing activity through which it can regulate PGE2 production (Bresson et al., 2012), thus contributing to the modulation of inflammation. In turn, AKR1B1 can bind several PG, including PGE1 and PGE2 and their cyclopentenone products, PGA1 and PGA2, which results in inhibition of the enzyme (Díez-Dacal et al., 2016). However, whereas binding and inhibition by PGE appear to be fully reversible, cyPG form a Michael adduct that seems irreversible under certain conditions. Nevertheless, concentrations of GSH in the cellular range (millimolar) elicit a retro-Michael reaction, a fact that contributes to explain the more intense modification and inhibition of some AKRs detected in GSH-depleted cells (Díez-Dacal et al., 2011).

AKR1B1 in allergic reactions

Early reports linking AKR1B1 to hypersensitivity provided fragmented pieces of evidence. The AKR1B1 inhibitor sorbinil, not currently used in clinical practice, elicited severe adverse effects, including hypersensitivity attributed to protein adducts produced by sorbinil metabolites (Maggs and Park, 1988). Interestingly, lodoxamide tromethamine, and several anti-allergy drugs, inhibit AKR1B1 (White, 1981), providing additional possibilities of interaction with the hypersensitivity response.

Recent studies using pharmacological or genetic depletion establish a positive role for AKR1B1 in allergy. In mice, AKR1B1 inhibition reduced airway inflammation, hyperresponsiveness and IgE and Th2-cytokine levels in ovalbumin and ragweed pollen extract-induced asthma (Yadav et al., 2009, 2011a). Furthermore, studies in AKR−/− mice also support a role of AKR1B1 in the pathogenesis of asthma and allergic rhinitis (Yadav et al., 2011b, 2013a). Moreover, the efficacy of AKR1B1 inhibitors in mouse models supports their use to treat these allergic conditions (Yadav et al., 2011b, 2013a). In mice sensitized with ovalbumin, AKR1B1 inhibition with fidarestat prevented the airway remodeling observed in chronic asthma by blocking the tumor growth factor β (TGFβ), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/Protein kinase B (PKB/AKT)/Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK3B) axis (Yadav et al., 2013b).

The mechanisms linking AKR1B1 with allergy are not fully understood. Nevertheless, it could be hypothesized that it provides coactivators of the allergic response through its contribution to oxidative stress or to the generation of proinflammatory mediators, like aldehyde conjugates.

In contrast to the numerous studies on GSTP1-1 polymorphisms in allergic patients, most genetic studies on AKR1B1 have been directed to explore its association with the development of diabetic implications (Demaine, 2003), and very little information exists on the impact of AKR1B1 variants on drug metabolism or hypersensitivity reactions. Nevertheless, given the fact that an increased glucose flux through the polyol pathway leads to redox imbalance, it would be interesting to assess the involvement of AKR1B1 variants in oxidative stress. In addition, the recent evidences on the involvement of AKR1B1 in allergy grant its study in association with these processes.

In summary, AKR and GST enzymes are emerging as important regulators of the balance of inflammatory mediators. This, together with their association with allergic processes and their ability to metabolize and be covalently modified by drugs makes them attractive candidates to explore their involvement not only in allergy in general but in drug hypersensitivity.

Author contributions

FS contributed to manuscript writing, figure preparation and experimental work. BD contributed to manuscript writing and figure preparation. EG contributed to manuscript writing. JA contributed to manuscript writing. MP contributed to manuscript writing. DP coordinated and wrote the manuscript and prepared figures.

Funding

This work has been supported by grants SAF2012-36519 from MINECO and SAF-2015-68590-R from MINECO/FEDER and ISCIII RETIC RIRAAF RD12/0013/0008 to DP, and RD12/0013/0002 to JA.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ade N., Leon F., Pallardy M., Peiffer J. L., Kerdine-Romer S., Tissier M. H., et al. (2009). HMOX1 and NQO1 genes are upregulated in response to contact sensitizers in dendritic cells and THP-1 cell line: role of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway. Toxicol. Sci. 107, 451–460. 10.1093/toxsci/kfn243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler V., Yin Z., Fuchs S. Y., Benezra M., Rosario L., Tew K. D., et al. (1999). Regulation of JNK signaling by GSTp. EMBO J. 18, 1321–1334. 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates N. A., Tursen U., Tamer L., Kanik A., Derici E., Ercan B., et al. (2004). GlutathioneS-transferase polymorphisms in patients with drug eruption. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 295, 429–433. 10.1007/s00403-003-0446-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains O. S., Grigliatti T. A., Reid R. E., Riggs K. W. (2010). Naturally occurring variants of human aldo-keto reductases with reduced in vitro metabolism of daunorubicin and doxorubicin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 335, 533–545. 10.1124/jpet.110.173179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains O. S., Takahashi R. H., Pfeifer T. A., Grigliatti T. A., Reid R. E., Riggs K. W. (2008). Twoallelic variants of aldo-keto reductase 1A1 exhibit reduced in vitro metabolism of daunorubicin. Drug Metab. Dispos. 36, 904–910. 10.1124/dmd.107.018895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranczyk-Kuzma A., Sawicki J. (1997). Biotransformation in monkey brain: coupling of sulfation to glutathione conjugation. Life Sci. 61, 1829–1841. 10.1016/S0024-3205(97)00807-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski O. A., Tipparaju S. M., Bhatnagar A. (2008). Thealdo-keto reductase superfamily and its role in drug metabolism and detoxification. Drug Metab. Rev. 40, 553–624. 10.1080/03602530802431439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaiya P., Roychowdhury S., Vyas P. M., Doll M. A., Hein D. W., Svensson C. K. (2006). Bioactivation, protein haptenation, and toxicity of sulfamethoxazole and dapsone in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 215, 158–167. 10.1016/j.taap.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S., Sinha K., Sil P. C. (2014). Cytochrome P450s: mechanisms and biological implications in drug metabolism and its interaction with oxidative stress. Curr. Drug Metab. 15, 719–742. 10.2174/1389200215666141125121659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board P. G., Menon D. (2013). Glutathione transferases, regulators of cellular metabolism and physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1830, 3267–3288. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresson E., Lacroix-Pepin N., Boucher-Kovalik S., Chapdelaine P., Fortier M. A. (2012). The Prostaglandin F synthase activity of the human aldose reductase AKR1B1 brings new lenses to look at pathologic conditions. Front. Pharmacol. 3:98. 10.3389/fphar.2012.00098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A., Srivastava S., Petrash J. M., Bhatnagar A., Srivastava S. K. (1997). Activesite modification of aldose reductase by nitric oxide donors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1341, 217–222. 10.1016/S0167-4838(97)00084-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini E., Galbiati V., Nikitovic D., Tsatsakis A. M. (2013). Role of oxidative stress in chemical allergens induced skin cells activation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 61, 74–81. 10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deavall D. G., Martin E. A., Horner J. M., Roberts R. (2012). Drug-induced oxidative stress and toxicity. J. Toxicol. 2012:645460. 10.1155/2012/645460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Corso A., Dal Monte M., Vilardo P. G., Cecconi I., Moschini R., Banditelli S., et al. (1998). Site-specific inactivation of aldose reductase by 4-hydroxynonenal. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 350, 245–248. 10.1006/abbi.1997.0488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demaine A. G. (2003). Polymorphisms of the aldose reductase gene and susceptibility to diabetic microvascular complications. Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 1389–1398. 10.2174/0929867033457359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Dacal B., Gayarre J., Gharbi S., Timms J. F., Coderch C., Gago F., et al. (2011). Identificationof aldo-keto reductase AKR1B10 as a selective target for modification and inhibition by PGA1: implications for anti-tumoral activity. Cancer Res. 71, 4161–4171. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Dacal B., Pérez-Sala D. (2010). Anti-inflammatory prostanoids: focus on the interactions between electrophile signalling and resolution of inflammation. ScientificWorldJournal 10, 655–675. 10.1100/tsw.2010.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Dacal B., Pérez-Sala D. (2012). A-class prostaglandins: early findings and new perspectives for overcoming tumor chemoresistance. Cancer Lett. 320, 150–157. 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Dacal B., Sánchez-Gómez F. J., Sánchez-Murcia P. A., Milackova I., Zimmerman T., Ballekova J., et al. (2016). Molecular interactions and implications of aldose reductase inhibition by PGA1 and clinically used prostaglandins. Mol. Pharmacol. 89, 42–52. 10.1124/mol.115.100693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragovic S., Venkataraman H., Begheijn S., Vermeulen N. P., Commandeur J. N. (2014). Effect of human glutathione S-transferase hGSTP1-1 polymorphism on the detoxification of reactive metabolites of clozapine, diclofenac and acetaminophen. Toxicol. Lett. 224, 272–281. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S., Matsunaga T., Arai Y., Ikari A., Tajima K., El-Kabbani O., et al. (2014). Cloning and characterization of four rabbit aldo-keto reductases featuring broad substrate specificity for xenobiotic and endogenous carbonyl compounds: relationship with multiple forms of drug ketone reductases. Drug Metab. Dispos. 42, 803–812. 10.1124/dmd.113.056044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbiati V., Mitjans M., Lucchi L., Viviani B., Galli C. L., Marinovich M., et al. (2011). Further development of the NCTC 2544 IL-18 assay to identify in vitro contact allergens. Toxicol. In Vitro 25, 724–732. 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayarre J., Stamatakis K., Renedo M., Pérez-Sala D. (2005). Differential selectivity of protein modification by the cyclopentenone prostaglandins PGA1 and 15-deoxy-Δ12, 14-PGJ2: role of glutathione. FEBS Lett. 579, 5803–5808. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland F. D., Li Y. F., Saxon A., Diaz-Sanchez D. (2004). Effectof glutathione-S-transferase M1 and P1 genotypes on xenobiotic enhancement of allergic responses: randomised, placebo-controlled crossover study. Lancet 363, 119–125. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15262-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilot D., Loyer P., Corlu A., Glaise D., Lagadic-Gossmann D., Atfi A., et al. (2002). Liver protection from apoptosis requires both blockage of initiator caspase activities and inhibition of ASK1/JNK pathway via glutathione s-transferase regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49220–49229. 10.1074/jbc.M207325200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueant J. L., Gueant-Rodriguez R. M., Gastin I. A., Cornejo-Garcia J. A., Viola M., Barbaud A., et al. (2008). Pharmacogenetic determinants of immediate and delayed reactions of drug hypersensitivity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14, 2770–2777. 10.2174/138161208786369795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves I. P., Al Shahrani M., Wainwright L., Heales S. J. (2016). Drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Drug Saf. 39, 661–674. 10.1007/s40264-016-0417-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J. D., Flanagan J. U., Jowsey I. R. (2005). Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 45, 51–88. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heibein A. D., Guo B., Sprowl J. A., MacLean D. A., Parissenti A. M. (2012). Role of aldo-keto reductases and other doxorubicin pharmacokinetic genes in doxorubicin resistance, DNA binding, and subcellular localization. BMC Cancer 12:381. 10.1186/1471-2407-12-381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins A., Wu P., Reiss S., Dworski R. (2013). Glutathione S-transferase P1 Ile105Val polymorphism modulates allergen-induced airway inflammation in human atopic asthmatics in vivo. Clin. Exp. Allergy 43, 527–534. 10.1111/cea.12086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio A., Polimanti R., Piacentini S., Liumbruno G. M., Manfellotto D., Fuciarelli M. (2014). Deletion polymorphism of GSTT1 gene as protective marker for allergic rhinitis. Clin. Respir. J. 9, 481–486. 10.1111/crj.12170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam T., Berhane K., McConnell R., Gauderman W. J., Avol E., Peters J. M., et al. (2009). Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) P1, GSTM1, exercise, ozone and asthma incidence in school children. Thorax 64, 197–202. 10.1136/thx.2008.099366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata T., Minucci S., McGowan M., Carper D. (1997). Identification of a novel cis-element required for the constitutive activity and osmotic response of the rat aldose reductase promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32500–32506. 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jez J. M., Flynn T. G., Penning T. M. (1997). A new nomenclature for the aldo-keto reductase superfamily. Biochem. Pharmacol. 54, 639–647. 10.1016/S0006-2952(97)84253-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Penning T. M. (2007). Aldo-keto reductases and bioactivation/detoxication. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47, 263–292. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiserova K., Tang X. L., Srivastava S., Bhatnagar A. (2008). Role of nitric oxide in regulating aldose reductase activation in the ischemic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9101–9112. 10.1074/jbc.M709671200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E. S., Hwang J. S., Ham S. A., Park M. H., Kim G. H., Paek K. S., et al. (2014). 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 prevents oxidative injury by upregulating the expression of aldose reductase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Free Radic. Res. 48, 218–229. 10.3109/10715762.2013.860224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang E. S., Woo I. S., Kim H. J., Eun S. Y., Paek K. S., Chang K. C., et al. (2007). Up-regulation of aldose reductase expression mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and Nrf2 is involved in the protective effect of curcumin against oxidative damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43, 535–545. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. H., Jung Y. H., Kim H. Y., Seo J. H., Lee J. Y., Kwon J. W., et al. (2013). Effect of paracetamol use on the modification of the development of asthma by reactive oxygen species genes. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 110, 364.e1–369.e1. 10.1016/j.anai.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto Y., Nakamura Y., Naito Y., Torii Y., Kumagai T., Osawa T., et al. (2000). Cyclopentenone prostaglandins as potential inducers of phase II detoxification enzymes. 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin j2-induced expression of glutathione S-transferases. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 11291–11299. 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb N. S., Hunsaker L. A., Vander Jagt D. L. (1994). Aldosereductase-catalyzed reduction of acrolein: implications in cyclophosphamide toxicity. Mol. Pharmacol. 45, 797–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh K., Uchinami H., Yoshioka M., Seki E., Yamamoto Y. (2014). Nrf2 activation protects the liver from ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Ann. Surg. 260, 118–127. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavergne S. N., Wang H., Callan H. E., Park B. K., Naisbitt D. J. (2009). “Danger” conditions increase sulfamethoxazole-protein adduct formation in human antigen-presenting cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 331, 372–381. 10.1124/jpet.109.155374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. K., Regenold W. T., Shapiro P. (2002). Inhibition of aldose reductase enhances HeLa cell sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs and involves activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases. Anticancer Drugs 13, 859–868. 10.1097/00001813-200209000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Paek K. S., Kang E. S., Jang H. S., Kim H. J., Kang Y. J., et al. (2005). Involvement of nuclear factor kappaB in up-regulation of aldose reductase gene expression by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate in HeLa cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37, 2297–2309. 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. D., Atkins W. M. (2004). A novel antioxidant role for ligandin behavior of glutathione S-transferases: attenuation of the photodynamic effects of hypericin. Biochemistry 43, 12761–12769. 10.1021/bi049217m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Wang Y., Feng Q., Zhang H., Xue B., Shen J., et al. (2009). Recombinant protein glutathione S-transferases P1 attenuates inflammation in mice. Mol. Immunol. 46, 848–857. 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutter R., van Lieshout B., Folisi C. (2015). Reduced antioxidant and cytoprotective capacity in allergy and asthma. Ann. Am. Thorac Soc. 12(Suppl. 2) S133–S136. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201503-176AW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon R. C., Li D., McGarvie G., Ellis E. M. (2013). Aldo-keto reductases mediate constitutive and inducible protection against aldehyde toxicity in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochem. Int. 62, 113–121. 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs J. L., Park B. K. (1988). Drug-protein conjugates–XVI. Studies of sorbinil metabolism: formation of 2-hydroxysorbinil and unstable protein conjugates. Biochem. Pharmacol. 37, 743–748. 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90149-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manevich Y., Fisher A. B. (2005). Peroxiredoxin 6, a 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, functions in antioxidant defense and lung phospholipid metabolism. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 1422–1432. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manevich Y., Hutchens S., Tew K. D., Townsend D. M. (2013). Allelic variants of glutathione S-transferase P1-1 differentially mediate the peroxidase function of peroxiredoxin VI and alter membrane lipid peroxidation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 54, 62–70. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.10.556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsue H., Edelbaum D., Shalhevet D., Mizumoto N., Yang C., Mummert M. E., et al. (2003). Generation and function of reactive oxygen species in dendritic cells during antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 171, 3010–3018. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry D. J., Chakravarty P., Wolf C. R., Henderson C. J. (2015). Altered protein S-glutathionylation identifies a potential mechanism of resistance to acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 355, 137–144. 10.1124/jpet.115.227389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Lawrenson A. S., Berry N. G., Maggs J. L., French N. S., Back D. J., et al. (2014). Abacavir forms novel cross-linking abacavir protein adducts in patients. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 27, 524–535. 10.1021/tx400406p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minotti G., Menna P., Salvatorelli E., Cairo G., Gianni L. (2004). Anthracyclines: molecular advances and pharmacologic developments in antitumor activity and cardiotoxicity. Pharmacol. Rev. 56, 185–229. 10.1124/pr.56.2.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monick M. M., Samavati L., Butler N. S., Mohning M., Powers L. S., Yarovinsky T., et al. (2003). Intracellularthiols contribute to Th2 function via a positive role in IL-4 production. J. Immunol. 171, 5107–5115. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsch A., Emter R. (2008). Skinsensitizers induce antioxidant response element dependent genes: application to the in vitro testing of the sensitization potential of chemicals. Toxicol. Sci. 102, 110–119. 10.1093/toxsci/kfm259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley A. J., Lo Bello M., Nuccetelli M., Mazzetti A. P., Parker M. W. (1999). Theligandin (non-substrate) binding site of human Pi class glutathione transferase is located in the electrophile binding site (H-site). J. Mol. Biol. 291, 913–926. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orhan H., Sahin G. (2001). In vitro effects of NSAIDS and paracetamol on oxidative stress-related parameters of human erythrocytes. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 53, 133–140. 10.1078/0940-2993-00179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paumi C. M., Smitherman P. K., Townsend A. J., Morrow C. S. (2004). Glutathione S-Transferases (GSTs) inhibit transcriptional activation by the peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) ligand, 15-deoxy-Δ12, 14 prostaglandin J2 (15-d-PGJ2). Biochemistry 43, 2345–2352. 10.1021/bi035936+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning T. M., Drury J. E. (2007). Humanaldo-keto reductases: function, gene regulation, and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 464, 241–250. 10.1016/j.abb.2007.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrash J. M. (2004). Allin the family: aldose reductase and closely related aldo-keto reductases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61, 737–749. 10.1007/s00018-003-3402-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plebuch M., Soldan M., Hungerer C., Koch L., Maser E. (2007). Increase dresistance of tumor cells to daunorubicin after transfection of cDNAs coding for anthracycline inactivating enzymes. Cancer Lett. 255, 49–56. 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak N., Dolle C., Ziegler M. (2007b). The power to reduce: pyridine nucleotides–small molecules with a multitude of functions. Biochem. J. 402, 205–218. 10.1042/BJ20061638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak N., Niere M., Ziegler M. (2007a). NAD kinase levels control the NADPH concentration in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33562–33571. 10.1074/jbc.M704442200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana K. V., Fadl A. A., Tammali R., Reddy A. B., Chopra A. K., Srivastava S. K. (2006). Aldosereductase mediates the lipopolysaccharide-induced release of inflammatory mediators in RAW264.7 murine macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33019–33029. 10.1074/jbc.M603819200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana K. V., Srivastava S. K. (2010). Aldosereductase: a novel therapeutic target for inflammatory pathologies. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 17–20. 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gómez F. J., Díez-Dacal B., Pajares M. A., Llorca O., Pérez-Sala D. (2010). Cyclopentenone prostaglandins with dienone structure promote cross-linking of the chemoresistance-inducing enzyme glutathione transferase P1-1. Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 723–733. 10.1124/mol.110.065391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gómez F. J., Dorado C. G., Ayuso P. J., Agúndez A. G., Pajares M. A., Pérez-Sala D. (2013). Modulation of GSTP1-1 oligomerization by inflammatory mediators and reactive drugs. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 12, 162–171. 10.2174/1871528111312030002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gómez F. J., Gayarre J., Avellano M. I., Pérez-Sala D. (2007). Direct evidence for the covalent modification of glutathione-S-transferase P1-1 by electrophilic prostaglandins: implications for enzyme inactivation and cell survival. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 457, 150–159. 10.1016/j.abb.2006.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson J. P., Naisbitt D. J., Park B. K. (2006). Role of bioactivation in drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions. AAPS J. 8, E55–E64. 10.1208/aapsj080107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroer K. T., Gibson A. M., Sivaprasad U., Bass S. A., Ericksen M. B., Wills-Karp M., et al. (2011). Down regulationof glutathione S-transferase pi in asthma contributes to enhanced oxidative stress. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 128, 539–548. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz E. N., Devadason S. G., Khoo S. K., Zhang G., Bizzintino J. A., Martin A. C., et al. (2010). The role of GSTP1 polymorphisms and tobacco smoke exposure in children with acute asthma. J. Asthma 47, 1049–1056. 10.1080/02770903.2010.508856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H., Tsuchida S., Tamai K., Sato K. (1993). Identification of cysteine residues involved in disulfide formation in the inactivation of glutathione transferase P-form by hydrogen peroxide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 300, 137–141. 10.1006/abbi.1993.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. (2015). Cytoprotective and regulatory functions of glutathione S-transferases in cancer cell proliferation and cell death. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 75, 1–15. 10.1007/s00280-014-2566-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S., Chandra A., Ansari N. H., Srivastava S. K., Bhatnagar A. (1998). Identification of cardiac oxidoreductase(s) involved in the metabolism of the lipid peroxidation-derived aldehyde-4-hydroxynonenal. Biochem. J. 329(Pt 3), 469–475. 10.1042/bj3290469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. K., Ramana K. V., Bhatnagar A. (2005). Role of aldose reductase and oxidative damage in diabetes and the consequent potential for therapeutic options. Endocr. Rev. 26, 380–392. 10.1210/er.2004-0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. K., Yadav U. C., Reddy A. B., Saxena A., Tammali R., Shoeb M., et al. (2011). Aldosereductase inhibition suppresses oxidative stress-induced inflammatory disorders. Chem. Biol. Interact. 191, 330–338. 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M. W., Tsai C. H., Tung K. Y., Hwang B. F., Liang P. H., Chiang B. L., et al. (2013). GSTP1 is a hub gene for gene-air pollution interactions on childhood asthma. Allergy 68, 1614–1617. 10.1111/all.12298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamer L., Calikoglu M., Ates N. A., Yildirim H., Ercan B., Saritas E., et al. (2004). Glutathione-S-transferase gene polymorphisms (GSTT1, GSTM1, GSTP1) as increased risk factors for asthma. Respirology 9, 493–498. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tew K. D. (2007). Redoxin redux: emergent roles for glutathione S-transferase P (GSTP) in regulation of cell signaling and S-glutathionylation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 73, 1257–1269. 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend D. M., Manevich Y., He L., Hutchens S., Pazoles C. J., Tew K. D. (2009). Novel role for glutathione S-transferase pi. Regulator of protein S-Glutathionylation following oxidative and nitrosative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 436–445. 10.1074/jbc.M805586200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsch L., Folisi C., Akkerdaas J. H., Logiantara A., van de Pol M. A., van der Zee J. S., et al. (2015). Allergic sensitization is associated with inadequate antioxidant responses in mice and men. Allergy 70, 1246–1258. 10.1111/all.12674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Jagt D. L., Hassebrook R. K., Hunsaker L. A., Brown W. M., Royer R. E. (2001). Metabolism of the 2-oxoaldehyde methylglyoxal by aldose reductase and by glyoxalase-I: roles for glutathione in both enzymes and implications for diabetic complications. Chem. Biol. Interact. 130–132, 549–562. 10.1016/S0009-2797(00)00298-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veitch Z. W., Guo B., Hembruff S. L., Bewick A. J., Heibein A. D., Eng J., et al. (2009). Induction of 1C aldoketoreductases and other drug dose-dependent genes upon acquisition of anthracycline resistance. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 19, 477–488. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32832c484b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Tian F., Whitman S. A., Zhang D. D., Nishinaka T., Zhang N., et al. (2012). Regulation of transforming growth factor beta1-dependent aldose reductase expression by the Nrf2 signal pathway in human mesangial cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 91, 774–781. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal G. A., Schnuch A., Schulz T. G., Reich K., Aberer W., Brasch J., et al. (2000). Homozygous gene deletions of the glutathione S-transferases M1 and T1 are associated with thimerosal sensitization. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 73, 384–388. 10.1007/s004200000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzelberger K., Baba S. P., Thirunavukkarasu M., Ho Y. S., Maulik N., Barski O. A., et al. (2010). Postischemic deactivation of cardiac aldose reductase: role of glutathione S-transferase P and glutaredoxin in regeneration of reduced thiols from sulfenic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26135–26148. 10.1074/jbc.M110.146423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G. J. (1981). Inhibition of oxidative enzymes by anti-allergy drugs. Agents Actions 11, 503–509. 10.1007/BF02004713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Fan Y., Xue B., Luo L., Shen J., Zhang S., et al. (2006). Humanglutathione S-transferase P1-1 interacts with TRAF2 and regulates TRAF2-ASK1 signals. Oncogene 25, 5787–5800. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B., Wu Y., Yin Z., Zhang H., Sun S., Yi T., et al. (2005). Regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response by glutathione S-transferase P1 in RAW264.7 cells. FEBS Lett. 579, 4081–4087. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav U. C., Aguilera-Aguirre L., Boldogh I., Ramana K. V., Srivastava S. K. (2011b). Aldosereductase deficiency in mice protects from ragweed pollen extract (RWE)-induced allergic asthma. Respir. Res. 12:145. 10.1186/1465-9921-12-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav U. C., Mishra R., Aguilera-Aguirre L., Sur S., Bolodgh I., Ramana K. V., et al. (2013a). Prevention of allergic rhinitis by aldose reductase inhibition in a murine model. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 12, 178–186. 10.2174/1871528111312030004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav U. C., Naura A. S., Aguilera-Aguirre L., Boldogh I., Boulares H. A., Calhoun W. J., et al. (2013b). Aldosereductase inhibition prevents allergic airway remodeling through PI3K/AKT/GSK3beta pathway in mice. PLoS ONE 8:e57442. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav U. C., Naura A. S., Aguilera-Aguirre L., Ramana K. V., Boldogh I., Sur S., et al. (2009). Aldosereductase inhibition suppresses the expression of Th2 cytokines and airway inflammation in ovalbumin-induced asthma in mice. J. Immunol. 183, 4723–4732. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav U. C., Ramana K. V., Srivastava S. K. (2011a). Aldosereductase inhibition suppresses airway inflammation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 191, 339–345. 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying W. (2008). NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 179–206. 10.1089/ars.2007.1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorrilla S., Garzón B., Pérez-Sala D. (2010). Selective binding of the fluorescent dye 8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid to PPARγ allows ligand identification and characterization. Anal. Biochem. 399, 84–92. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]