Abstract

Aim:

Attitude toward death is one of the most important factors that can influence the behavior related to the health profession. It is thought that physicians are afraid of death more than other groups of specialist. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the attitudes of the medical students of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences toward death.

Materials and Methods:

This study is a cross-sectional study on 308 medical students of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences in the academic year of 2015. Attitudes were assessed through the questionnaire of death attitude profile-revised. The collected data were analyzed upon arrival to a computer with SPSS version 14, and descriptive and inferential statistical methods.

Results:

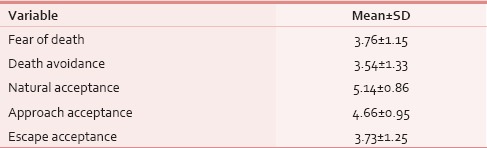

Attitude toward death was investigated in the 5 dimensions including the fear of death, death avoidance, approach acceptance, neutral acceptance, and escape acceptance. The results showed that the mean and standard deviations of fear of death, death avoidance, natural acceptance, approach acceptance, and escape acceptance were 3.76 ± 1.15, 3.54 ± 1.33, 5.14 ± 0.86, 4.66 ± 0.95, and 3.73 ± 1.25, respectively. It was found that people who have had the experience in dealing with death had less escape of the death attitude.

Conclusion:

Totally, the results of this study demonstrated that the medical students had good attitudes through 5 dimensions of attitudes toward death. This is probably due to the religious beliefs and also dealing with dying patients. However, it is recommended that training programs should be provided for students in the field of attitudes toward death.

Key words: Approach acceptance, Attitude toward death, Death avoidance, Escape acceptance, Fear of death, Medical students of Rafsanjan, Natural acceptance

INTRODUCTION

Death is an important part of human life, and human life alone is a process that changes over time in various forms.[1] Thinking about death has played an important role in human's life from the beginning of human civilization, and since the beginning of recorded human history, truth of death and human limitations in this area became a strong and shocking concern.[2]

Although death is a biological and psychological event and feelings about death and dying process rooted in how a person becomes social, it is scary to think about death, and most people prefer not to think about it.[2,3]

Several factors such as gender, experience of the death of relatives, religious factors, belief in the afterlife, belief in life after death, believing that all die 1 day, affect people's attitudes toward death.[4,5,6]

The medical community is faced with death and dying more than other people, but still talking about it even in training health-care workers is low.[1] Attitude toward death is one of the most important factors that will influence the behavior of health-care professionals.[7]

According to the scale of Wong et al., attitude to death is divided into two positive and negative categories. A positive attitude includes acceptance approach, neutral acceptance, and escape acceptance; and negative attitude includes fear of death and death avoidance.[8]

Numerous studies show that death anxiety in nurses and doctors has a great impact on communication and care of patients, especially dying patients.[9] Due to continuous exposure to patients and deaths and the liability arising from the profession, medical students are exposed to a lot of stress.[10] Harmon–Jones know the death anxiety as conscious and unconscious fear of death or dying.[11] Death anxiety is associated with generalized anxiety,[12] depression,[13] and suicidal ideation,[14] which all of these can lead to yield loss in a person.

Some investigators reported that there is a relationship between the attitude toward death and the care of dying patients.[15] Other studies have pointed out the relationship between personal experience with death and dying and their attitudes toward caring for dying people.[6] Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the attitudes of medical students of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences toward death in 2015.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a descriptive study that aimed to determine the attitudes of medical students of the Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences toward death in 2015. The research community consisted of all medical students in Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences studying in the academic year of 2014–2015, and sampling was performed in the census (assessment of all the society). The total study population consisted of 360 subjects who participated in the study, in that 324 subjects had full satisfaction. It should be noted that 16 subjects were excluded from the study due to incomplete answers and selecting “no idea” item for all questions of the questionnaire.

The data collection tool was a questionnaire consisting of two parts, the first section was the questions about demographic information including age, gender, marital status, year of entry, educational level, the history of dealing with dying patients, the years of training in the care of patients who were dying, and the history of dealing with the death of a close relative whereas the second part of the questionnaire included death attitude profile-revised (DAP-R), that its validity and reliability had been assessed in studies inside and outside of Iran.[16,17] The overall reliability of the questionnaire was achieved 82% using Cronbach's alpha while this efficiency was calculated in its components including fear of death, death avoidance, natural acceptance, approach acceptance, and escape acceptance as 0.84, 0.84, 0.62, 0.86, and 0.87, respectively. The questionnaire included 32 questions which evaluated these questions in the 5 dimensions of students’ attitudes toward death: The fear of death involved in the questions of 1, 2, 7, 18, 20, 21, and 32, the death avoidance involved in the questions of 3, 10, 12, 19, and 26, the natural acceptance involved in the questions of 6, 14, 17, 24, and 30, the approach acceptance involved in the questions of 4, 8, 13, 15, 16, 22, 25, 27, 28, and 31, and finally, escape acceptance involved in the questions of 5, 9, 11, 23, and 29, that the answers of questions were scored based on Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and the average score of each section was used for evaluation.

After explaining the purpose of this research, the questionnaire was distributed among the subjects and they were completed and collected in the presence of the researcher. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software version 14 (Version 14.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) after entering them into the computer. The quantitative data were reported as mean ± standard deviation and qualitative data for the number (percentage). To investigate the relationship between the attitudes and demographic characteristics, the independent t-test, Mann-Whitney test, ANOVA, and Pearson correlation coefficient were used. The level of significance was considered 0.05 for all tests.

Findings

The total study population of the present research consisted of 360 subjects, in that 324 subjects had full satisfaction. It should be noted that 16 patients were excluded due to incomplete answers and selecting “no idea” item for all questions of the questionnaire (response rate of 95.06%).

According to the results of the present study, the mean and standard deviation of age of the study subjects was 21.28 ± 2.16, and median, mode, minimum, and maximum ages were 21, 19, 18, and 26 years, respectively. In addition, 48.4% of the subjects were at the age group of 20-24 years.

Most of the samples were female (89.3%), single (89.3%), and they were studying in basic sciences course (54.5%). About 21.8% and 26.9% of the subjects had the experience of dealing with the death of patients and family members, respectively. While only 17 patients (5.5%) of the studied subjects had a background of training courses in the field of death.

According to the DAP-R questionnaire, the attitudes toward death were evaluated in 5 dimensions including fear of death, death avoidance, natural acceptance, approach acceptance, and escape acceptance. The mean and standard deviations scores of fear of death, death avoidance, natural acceptance, approach acceptance, and escape acceptance in the samples of the research were 3.76 ± 1.15, 3.54 ± 1.33, 5.14 ± 0.864, 4.66 ± 0.95, and 3.73 ± 1.25, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of samples frequencies based on the average scores of attitude towards death

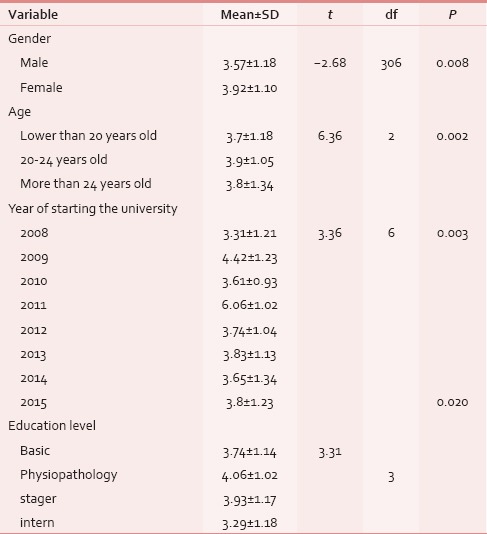

The results demonstrated that the mean score of the fear of death was higher in the female students than male students (female students had more fear of death), that this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.008). In addition, the mean of fear of death was higher in the age group of 20-24 years rather than other groups, and the lowest fear of death was observed in the group under 20 years. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.002). The correlation between the fear of death and marital status was not statistically significant. However, there was a significant difference between the year of starting the university and the fear of the death so that it was higher in the students who started university at 2009 compared to other groups of entrance years (P = 0.003). In addition, the mean of fear of death was significant due to the education level so that the fear of death was higher than other grade levels in the pathophysiology period, and the lowest was observed in the interns group (P = 0.02). The correlation between the fear of death with the experience of dealing with the death of patients, experience of dealing with the death of a close relative, and spending training courses about the history of death was not statistically significant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean of the fear of death with gender, age, entrance year, and grade level of the studied subjects

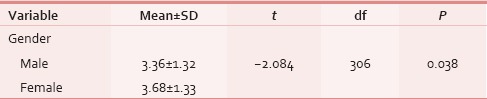

There was an average death avoidance among female students than male students, this difference was statistically significant in this case that the avoidance of death was seen among female students (P = 0.038). The correlation between the death avoidance and the factors including age, marital status, the year of entrance and the level of education, the experience of dealing with the death of patients, experience of dealing with the death of a close relative, and also spending the training courses about the death was not statistically significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of death avoidance in the studied subjects related to the gender

The correlation between the natural acceptance in the studied subjects with age, sex, marital status, educational level, the experience of dealing with the death of patients, the experience of dealing with the death of close relatives, and spending training courses on the history of death was not significant.

The mean natural acceptance was highest among the students who entered in 2010 and 2014 years whereas the lowest level of this index was observed in the students who entered into the university at 2009, while the difference was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.0001).

The correlation between the approaches of acceptance to the death in people with the age, sex, marital status, year of entrance, educational level, the experience of dealing with the death of patients, the experience of dealing with the death of a close relative, and spending the courses about the death was not significant.

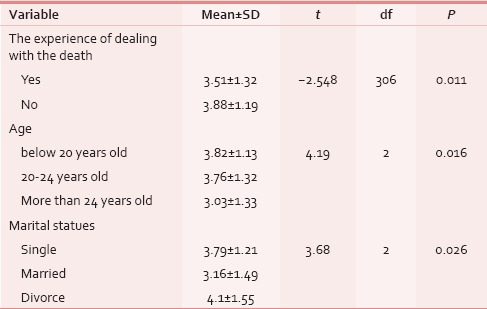

No significant correlation was observed between the mean escape acceptance and gender, the experience of dealing with the death of a close relative, and spending the training course about death. However, the mean escape of death was higher in the students who did not have an experience dealing with the death of patients and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.01).

Mean escape acceptance in the age group below 20 years was higher than other groups while this attitude had the lowest mean in the age group more than 24 years and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.01). Furthermore, the attitude of escape of death was more than other two groups in the divorced people. The lowest rate of escape from life through the death was achieved among the married people, and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.02). In addition, the correlation between the mean escape of death and the entrance years and the level of education was not significant [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of Escape Acceptance of the studied subjects related to the experience of dealing with dying patients, age, and marital status

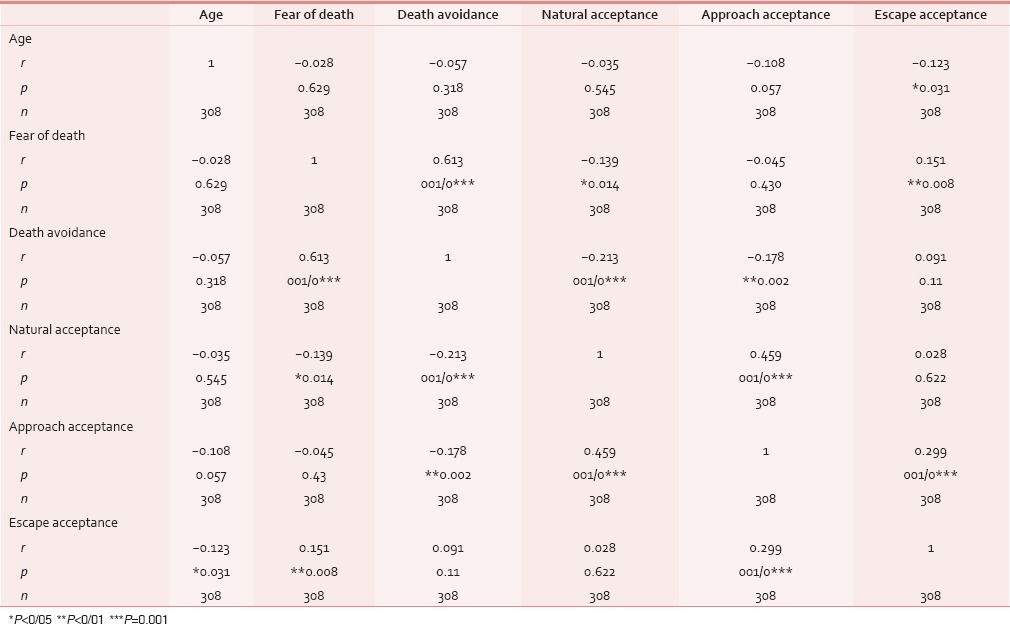

The results showed that between 5 dimensions of attitude toward death and age, there was no significant relationship (P > 0.05). In addition, the results of Pearson correlation coefficient revealed that there was a direct significant relationship between fears of death with death avoidance (r = 0.613, P = 0.001) and escape acceptance (r = 0.151, P = 0.008) and an indirect significant relationship with approach acceptance (r = −0.139, P = 0.014).

The results of Pearson correlation coefficient showed that there was a direct significant relationship between death avoidance with fears of death (r = 0.613, P = 0.001), an indirect significant relationship with approach acceptance (r = −0.213, P = 0.001), and a neutral acceptance (r = −0.178, P = 0.002). In addition, there was a direct significant relationship between approach acceptance with neutral acceptance (r = 0.459, P = 0.001) and an indirect significant relationship with fear of death (r = −0.139, P = 0.014) and death avoidance (r = −0.213, P = 0.001).

There was a direct significant relationship between neutral acceptance with approach acceptance (r = 0.459, P = 0.001) and escape acceptance (r = −0.299, P = 0.001) and an indirect significant relationship with death avoidance (r = −0.178, P = 0.002). There was a direct significant relationship between escape acceptance with fear of death (r = −0.151, P = 0.008) and a neutral acceptance (r = −0.299, P = 0.001) [Table 5].

Table 5.

The relationship between age and the dimensions of attitudes toward the death

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to determine the attitude of medical students of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences toward death, and the response rate was 95.06%.

The results showed that the studied population was in a good condition in the fear of death. The comparison of the results of the present research and the study of Bagherian et al. demonstrated that the students of Kerman were in better conditions that it was probably due to the lack of assistant students at the center and more connection of students with the patients. However, this scale in the similar research in Bam had lower scores that were obtained probably because most of these students are faced with death in the incident on January 2004.[17]

The results also demonstrated that the fear of death had a significant relationship with the variables including age groups, gender, marital status, and the entrance years, that these were consistent with the results of Hegedus et al.[18] In addition, these results were opposed to the results of Wong et al. (although the mean in men was more than women, but the gender had no effect on the average score of the fear of death).[16]

The findings of Hegedus et al. showed a reduction in the fear of death following the teaching courses of the medical students. In addition, the age, gender, and also the experience of the fear of death also affected the level of fear of death. The most important factor influencing the improvement of the attitude toward death was the increased awareness in the care of dying patients that was consistent with the results of the present study.[18]

In the present study, no significant relationship was observed between fears of death and clinical experience in the medical students. Howells et al. had found no significant difference between the students who had the clinical experience and who had no fear of death,[19] which was consistent with the results of this research.

The results also showed that the level of fear of death in the ages from 20 to 24 was higher than the other two groups that were suggested to be due to the changes in thoughts during this age period. In terms of the gender, the fear of death was significantly higher in the female students that it is likely because of the overall anxiety level of this group about all issues. In the present research, evaluation of the marital status revealed that the divorced people had higher fear of death whereas the married people had lower fear death. The divorced people had faced with so much mental stress and pressure that it can be the reason of increased the basic fear, whereas the married people had lower level of fear of death due to the relaxation that was developed after the marriage and their future. Studying the correlation between the fear of death and the entrance year to the university demonstrated that the entrance of the year 2009 had the highest fear of death. It is possible that the students who had entered at the mentioned year will have increased anxiety and fear in the absence of the professors and assistants during the future few months and after passing the preinternship examination and starting the intern period when they will have to deal with the dying patients. The mean fear of death was higher in the students studying in the pathophysiology section that it seems to be due to their primary knowledge of the diseases in this section and lack of the clinical insight to diseases, as the mean was lowest among the intern students.

In addition, a significant correlation was not found between the fear of death and having training courses and fear of death. Study of Asadpour et al. who had reviewed the attitudes of the nursing service personnel toward death demonstrated a significant relationship between the fear of death and gender, occupation, work experience in Intensive Care Unit, and having training courses in the field of death. They stated that provision of the appropriate training and retraining courses with the aim of reducing the fear of death led to improvement of attitudes toward death and also caused personnel to providing the health-care services considering death as a part of life; so they could help the patients and their families better.[20]

In a study by Kim et al. (2009), the results showed that the training programs increased life satisfaction significantly, but had no significant effect on attitudes toward death.[21]

Mean of death avoidance was in a desirable situation and it was correlated with the gender so that female students tried to avoid thinking about death that was opposed to the results of a study by Paul et al. (1994) (gender influenced the mean score of avoiding the death on the way that the scores of men were higher than women).[16]

The research of Asadpour et al. showed that nursing care personnel poorly or moderately had death avoidance; while there was a significant relationship between the death avoidance, and occupation, family income, age, and work experience. That research demonstrated that as age and work experience were increased, the death avoidance was decreased among the health care-providing personnel because they have probably better recognition, higher knowledge, and reduced anxiety rather than other groups.[20]

Bagherian et al. studied the nurses of Valiasr hospital and found that most of the nurses tended to provide care of dying patients and talk to their families or teach useful thing in this field.[22]

Attitude toward death was negative in the research of Hegedus et al. and many of the subjects tried to avoid dealing with the questions related to the concerns of dying patients and if they dealt with such questions, they used more difficult ways to avoid responding to the questions. Most physicians in Hungary had a very little knowledge about death and dying. Researchers in their study stated that a low knowledge, fear of death, and death avoidance can have a negative impact on the dying patients.[18]

The results of the present study showed that the studied population was in a good condition on the approach acceptance. There was a significant correlation between the approach acceptance and the entrance year so that students who started their university course at 2014 expressed the highest level of approach acceptance. The highest level of acceptance in this group who started their study in the medical field may be due to the lower level of awareness of the incurable diseases and their clinical conditions rather than the students at the highest grades.

Afrasiabifar et al. found that subjects had appropriate knowledge of the psychological and physical caring for the dying patients so that most of them had a positive attitude and performance, and there was a significant relationship between the knowledge level and attitude toward death.[23]

Results of the present research revealed that the studied population was in a good condition on the neutral acceptance. These findings can be explained by the religious beliefs of the students toward Islam and thoughts of resurrection after earthly life so that most of the subjects stated that one of the reasons of relaxation when facing the death was their belief to the life after the death.

Bagherian et al. demonstrated that students in Bam considered death as an escape from the terrible life while the students in Kerman considered it as a way to enter the life after death. The average students who considered death as a way to enter the afterlife in Bam were 3.94[17] that this rate was lower than the research community as 4.66. In a research in the Valiasr hospital of Tehran, this criterion[2,6] was also less than the statistical population. It demonstrates that the students of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences had probably higher religious insights toward death.

Zargham-Boroujeni et al. showed in their research that one of the main viewpoints that helps nurses to better deal with the phenomenon of death was belief in life after death. Recognizing the death as a fate of all living organisms can also bring peace to the human. This view not only leads to relaxation of the nurses, but also helps them to develop the relaxation in dying patients and their relatives. In this research, the drawn picture of death by the nurses is a spiritual image. They believe that nursing employment has increased this spirituality so that they have less uncertainty about life after death.[24]

Jo et al. studied the attitude toward death in the students of South Korea and stated that attitudes toward death among the students were different based on the belief to death; while attitudes toward death were correlated to the self-efficacy, depression, and life satisfaction. The main predictor of attitudes toward death was life satisfaction.[25]

Studying the escape acceptance in this research showed that the studied population was in a good situation. There was a significant relationship between escape acceptance and age group, experience dealing with the death of patient, and marital status. Comparison of the three age groups revealed that in ages >24 years, students considered death as a way of escape from life, whereas this attitude was higher in the students <20-year-old. It should be due to the mental maturity with the passage of time and having more life experiences. In this study, it was found that people who had experience dealing with the death had a better attitude toward death by the escape acceptance and this rate was lower in them.

Bagherian et al. found that students in Bam considered death as a way for escape from the painful life more than the Kerman students. They stated that the experience of dealing with death with education in the field of death were the two affective factors on the attitudes toward death.[17]

Anderson et al. showed that students who had experience dealing with dying patients during the college period have expressed more positive attitudes about death.[26]

Lange et al. found a significant correlation between the age, treatment experience, the history of dealing with the dying patients, and attitude toward the death. As the three factors are increased, positive attitude toward death is increased and also the attitude toward provision of the clinical services to the dying patients is also improved.[27] Rooda et al. found that dealing with dying patients and gender influenced the attitude of death.[4]

The results showed that the fear of death had a direct correlation with the death avoidance. Results of this research demonstrated that people who were more afraid of death were mostly trying to avoid this inevitable phenomenon. The fear of death had an inverse correlation with the approach acceptance. In other words, people who had no fear of death, more accepted death as a part of life and an inevitable and undeniable phenomenon. This study revealed that the fear of death was correlated with the attitude of escape acceptance. It should be noted that students who had escaped from life thoughts had no suicide attempts because they were afraid of death.

The correlation analysis of death avoidance showed an inverse relation with the approach acceptance that seems to be reasonable. Evaluation of death avoidance and the neutral acceptance also showed a reverse correlation. It can be expressed that people who have little faith in the life after death, avoid the death mostly. Approach acceptance had a direct correlation with the neutral acceptance. People who had more faith had more acceptance of death as an inevitable look.

Studying the relationship between the neutral acceptance and escape acceptance demonstrated a significant relationship. These findings can be explained in a way that some people who had strong faith in the afterlife, penetrated the escape through death in their thoughts due to the main problems in their lives and the helpless in the world to be released from the worldly problems and be moved to paradise.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall results of the present research showed that students of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences had a good attitude toward death in 5 dimensions that this may be due to direct dealing with dying patients and religious beliefs and considering death as a bridge to the afterlife.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the moral and material support of respected colleagues and students of medicine field and students of College of Medicine, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, who participated in the study with a good reception.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beall JW, Broeseker AE. Pharmacy students’ attitudes toward death and end-of-life care. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74:104. doi: 10.5688/aj7406104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Khalek AM, Tomás-Sábado J. Anxiety and death anxiety in Egyptian and Spanish nursing students. Death Stud. 2005;29:157–69. doi: 10.1080/07481180590906174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feifel H. Psychology and death. Meaningful rediscovery. Am Psychol. 1990;45:537–43. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rooda LA, Clements R, Jordan ML. Nurses’ attitudes toward death and caring for dying patients. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:1683–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russac RJ, Gatliff C, Reece M, Spottswood D. Death anxiety across the adult years: An examination of age and gender effects. Death Stud. 2007;31:549–61. doi: 10.1080/07481180701356936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke KJ, Durlak JA. Impact of life factors upon attitudes toward death. Omega (Westport) 1990;21:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wessel EM, Garon M. Introducing reflective narratives into palliative care home care education. Home Healthc Nurse. 2005;23:516–22. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200508000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nozari M, Dousti Y. Attitude toward death in healthy people and patients with diabetes and cancer. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2013;6:95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deffner JM, Bell SK. Nurses’ death anxiety, comfort level during communication with patients and families regarding death, and exposure to communication education: A quantitative study. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2005;21:19–23. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamid N, Ataie Moghanloo V, Eydi Baygi M. Comparison the relationship between mental health and hardiness in first and last semester medical students. Jentashapir J Health Res. 2012;3:273–81. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmon-Jones E, Simon L, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S, McGregor H. Terror management theory and self-esteem: Evidence that increased self-esteem reduces mortality salience effects. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:24–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Khalek AM. Death anxiety among Lebanese samples. Psychol Rep. 1991;68(3 Pt 1):924–6. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.68.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Templer DI, Lavoie M, Chalgujian H, Thomas-Dobson S. The measurement of death depression. J Clin Psychol. 1990;46:834–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199011)46:6<834::aid-jclp2270460623>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Attilio JP, Campbell B. Relationship between death anxiety and suicide potential in an adolescent population. Psychol Rep. 1990;67(3 Pt 1):975–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.67.7.975-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloway M. Death the great leveller? Towards a transcultural spirituality of dying and bereavement? J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:833–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong PT, Reker GT, Gesser G. Death attitude profile-revised (DAP-R): A multidimensional measure of attitudes towards death. In: Neimeyer RA, editor. Death Anxiety Handbook: Research, Instrumentation, and Application. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis; 1994. pp. 121–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagherian S, Iranmanesh S, Abbasszadeh A. Comparison of bam and kerman nursing students’ attitude about death and dying. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2010;9:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegedus K, Zana A, Szabó G. Effect of end of life education on medical students’ and health care workers’ death attitude. Palliat Med. 2008;22:264–9. doi: 10.1177/0269216307086520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howells K, Gould M, Field D. Fear of death and dying in medical students: Effects of clinical experience. Med Educ. 1986;20:502–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asadpour M, Bidaki R, Rajabi Z, Mostafavi SA, Khaje-Karimaddini Z, Ghorbanpoor MJ. Attitude toward death in nursing staffs in hospitals of Rafsanjan (South East Iran) Nurs Pract Today. 2015;2:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EH, Lee E. Effects of a death education program on life satisfaction and attitude toward death in college students. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009;39:1–9. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2009.39.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagherian S, Iranmanesh S, Dargahi H, Abbas Zadeh A. The attitude of nursing staff of institute cancer and Valie-Asr hospital toward caring for dying patients. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2010;9:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afrasiabifar A, Mohammad Hosseini S, Momeni A, ALAMDARI AK. Knowledge, attitude and practice of nurses in relation to taking care of dying patients in yasuj medical sciences university hospital in 2002. Armaghan Danesh. 2003;8:91–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zargham-Boroujeni A, Bagheri SH, Kalantari M, Talakoob S, Samooai F. Effect of end-of-life care education on the attitudes of nurses in infants’ and children's wards. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2011;16:93–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jo KH, Lee HJ. Relationship between self-efficacy, depression, level of satisfaction and death attitude of college students. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2008;38:229–37. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2008.38.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson WG, Williams JE, Bost JE, Barnard D. Exposure to death is associated with positive attitudes and higher knowledge about end-of-life care in graduating medical students. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1227–33. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange M, Thom B, Kline NE. Assessing nurses’ attitudes toward death and caring for dying patients in a comprehensive cancer center. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:955–9. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.955-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]