Abstract

Background

Patients with an unused/malfunctioning implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) lead may have the lead either abandoned or explanted; yet there are limited data on the comparative acute and longer-term safety of these 2 approaches.

Methods and Results

We examined in-hospital events among 24,908 subject encounters using propensity score 1:1 matching for ICD lead abandonment or explantation in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) ICD Registry (April 2010 – June 2014). Relative to patients undergoing lead abandonment, patients undergoing lead explantation had more in-hospital procedure-related complications 2.19% (n=273) versus 3.77% (n=469) (p<0.001), respectively. Similarly, patients undergoing lead explantation had slightly higher rates of in-hospital death 0.21% (n=26) versus 0.64% (n=80) (p<0.001) respectively. At 1 year in a Medicare subset for survival, there was a trend of increased mortality in the explantation group (11% vs. 8%; [p=0.06]). In the Medicare subset analyzed for post-procedure complications, there was no difference with respect to 6-month bleeding (4.80% in both groups), tamponade (0.38% vs 0.58%), infection (1.34% vs 3.07%), upper extremity thrombosis (0.77% vs 0.96%), pulmonary embolism (0.38% vs 0.96%), or urgent surgery (1.15% for both groups) (p>0.05 for all).

Conclusions

After matching, patients undergoing removal of an unused/malfunctioning ICD lead had slightly higher in-hospital complications and deaths than those with a lead abandonment strategy. Although the 1-year mortality risk was higher in the lead explantation group, this difference may be explained by chance.

Keywords: implanted cardioverter defibrillator, comparative effectiveness, survival analysis, complication, lead explantation

Background

The implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) prevents sudden cardiac death in patients with a history of sudden cardiac arrest and in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. 1-4 Since the widespread adoption of ICD therapy for primary prevention, the number of patients with ICDs has risen substantially with nearly 150,000 new implants in 2009 alone (the most recent data available).5 Device infection remains a common reason for system revision and one that usually necessitates system explantation,6, 7 but when lead replacement is indicated for other reasons (e.g., lead fracture), there are two potential approaches to managing the existing lead: explantation or abandonment. To date, data comparing management strategies of unused/malfunctioning ICD leads have been limited to single center studies some of which examined lead explantation and lead abandonment in isolation,8-11 while others compared these strategies to one another. 12, 13,14, 15 Thus, in the absence of a large, multicenter comparison of real world outcomes, the relative risks and benefits of each approach remain unclear.

Using data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) ICD Registry (the “Registry”) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) we conducted a study to compare characteristics of patients, providers, and facilities associated with abandonment or explantation of an unused/malfunctioning ICD lead and examine both acute and longer term outcomes associated with these different management strategies.

Methods

Data Sources

Data for this investigation were acquired from two sources: the NCDR ICD Registry and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The NCDR ICD Registry has been described previously. 16 Briefly, it was launched in 2005 by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) to meet a CMS mandate requiring data submission on all Medicare beneficiaries receiving a primary prevention ICD. Since launching of this Registry, a large majority of participating hospitals submit data on all ICD implants. In 2010, a “leads only” data collection form was added to capture characteristics of ICD procedures not involving generator placement or replacement. Registry data are submitted via a secure website and are subject to rigorous electronic quality checks. Although there is significant variability between data elements, formal auditing of data entered into the Registry demonstrated overall raw data accuracy of 91.2%. 29

Medicare data include inpatient and outpatient claims and the corresponding denominator files for 2010 through 2011. We linked the Registry data to Medicare claims using a combination of indirect identifiers including age, sex, admission date, procedure date, and hospital identification for the examination of post-procedure survival and complications.

Study Population

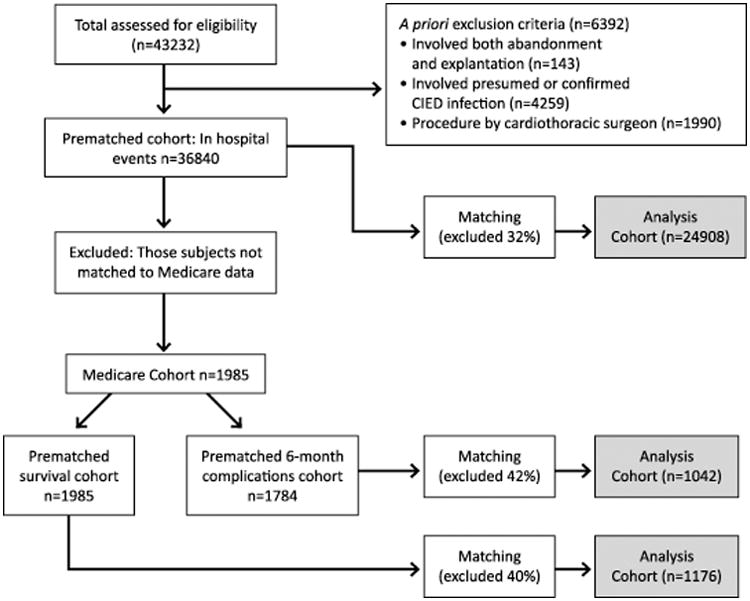

To study procedural complications, we included all patient encounters involving either defibrillator lead abandonment or explantation in the NCDR ICD Registry from April 2010 to June 2011 (n=43,232) (Figure 1). We use the term “explantation” rather than “extraction” because we were not able to exclude procedures involving simple traction techniques versus true extraction. Many pace-sense lead procedures are also captured in the Registry, so all lead models had to be characterized manually as transvenous pacing only lead versus transvenous defibrillator lead versus other (e.g., epicardial, coronary sinus) in order to capture abandonment or explantation of transvenous defibrillator leads only. Procedures were assigned to the lead abandonment versus explantation groups based on the management of the defibrillator lead regardless of whether any other leads were involved in the procedure. Patient encounters were excluded if they involved a procedure that included both abandonment and explantation (n=143) or if there was evidence of definite or presumed ICD infection since this would generally be an indication for system explantation (n=4,259). Patient encounters with the procedure performed by a cardiothoracic surgeon were excluded (n=1,990) since it was assumed that lead explantation was predetermined in these cases. This resulted in an analysis cohort of 36840 patient encounters in 1241 facilities.

Figure 1. Development of the three analysis cohorts from the NCDR ICD Registry and Medicare claims.

To study post-procedure survival, we limited our analysis to those patients who could be matched to Medicare enrollment files that include post-discharge information on all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older. Patient data in the Registry were merged with Medicare Part A inpatient claims, matching by patients' age, admission date or procedure date, sex, and hospital. As a result, we identified 1,985 patient encounters from 1,980 patients who were Medicare eligible at any time during follow up for a survival analysis.

Lastly, to evaluate complications up to six-months post-discharge, we excluded 201 patient encounters from the Medicare cohort in which the patient was not insured by Medicare either at the time of the procedure or over the course of the six-month follow up since we could not confirm capture of complications without this consistency in Medicare insurance. This analysis included 1,784 patient encounters in 1,780 unique Medicare patients.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this analysis was in-hospital procedure-related complications or death from the NCDR ICD Registry from April 2010 through June 2014. Each outcome was examined individually and by severity (major versus minor) as has been done previously. 17 Secondary outcomes for Medicare patients included (1) all-cause mortality at discharge, 90 days, and one year; patients with no record of death in the denominator file were considered alive as of May 3, 2012 or the date at which the patient was no longer enrolled in Part A & Part B fee-for-service Medicare, whichever came first and (2) incidence of bleeding, tamponade, infection, need for urgent surgery, upper extremity thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism at six months as determined by relevant ICD-9 codes (Supplemental Material). Six month complication outcomes were chosen to reflect the period of time during which a complication could reasonably be attributed to the abandonment or explantation procedure.

Statistical analysis

We compared baseline characteristics between the lead abandonment and lead explantation groups. Most baseline characteristics were available directly from the Registry; however, the number of high voltage coils on the defibrillator lead undergoing revision is not included in the Registry, but this characteristic has been established as critical. Accordingly, for each lead model recorded in the data set, coil number was determined manually through a combination of searching manufacturer websites and catalogs, and, when necessary, through direct telephone contact with manufacturer customer support. Continuous variables were compared using T tests, and categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test. Summaries of these descriptive analyses are reported as percentages for categorical variables and as means and standard deviations for continuous variables. The standardized difference for each variable, defined as the absolute difference in means (or proportions) divided by the average standard deviation, is also reported for each variable.

In-hospital death, in-hospital procedural complications, and in-hospital death or procedure events were compared between unmatched groups using logistic regression models. Categories of independent variables were added into the model in the following order: none, medical history, procedural characteristics, hospital characteristics, and operator characteristics listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics with standardized difference before and after matching in the overall NCDR ICD Registry cohort.

| Description | Before Matching | After Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Abandonment [# (%) or mean (std)] | Lead Explantation [# (%) or mean (std)] | ASD* | Lead Abandonment [# (%) or mean (std)] | Lead Explantation [# (%) or mean (std)] | ASD | |

| All | 20918 (100) | 15922 (100) | 12454 (100) | 12454 (100) | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, yrs | 68.20 (12.70) | 62.57 (14.34) | 42 | 65.40 (13.23) | 64.97 (12.79) | 3 |

| Gender: Female | 5587 (26.71) | 4753 (29.85) | 7 | 3479 (27.93) | 3504 (28.14) | 0 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 16948 (81.02) | 12857 (80.75) | 1 | 9980 (80.13) | 10033 (80.56) | 1 |

| Medical History | ||||||

| Heart Failure | 14711 (70.33) | 9953 (62.51) | 7 | 8508 (68.32) | 8380 (67.29) | 2 |

| NYHA Functional Classification† | ||||||

| - Class I | 3984 (19.05) | 3175 (19.94) | 2 | 2363 (18.97) | 2444 (19.62) | 2 |

| - Class II | 7402 (35.39) | 4847 (30.44) | 11 | 4138 (33.23) | 4074 (32.71) | 1 |

| - Class III | 6758 (32.31) | 4702 (29.53) | 6 | 3995 (32.08) | 3941 (31.64) | 1 |

| - Class IV | 390 (1.86) | 265 (1.66) | 2 | 245 (1.97) | 224 (1.80) | 1 |

| Non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy | 6051 (28.93) | 4882 (30.66) | 11 | 3859 (30.99) | 3857 (30.97) | 1 |

| Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter | 7471 (35.72) | 4702 (29.53) | 8 | 4066 (32.65) | 4012 (32.21) | 0 |

| Ventricular Tachycardia | 9527 (45.54) | 6284 (39.47) | 6 | 5266 (42.28) | 5243 (42.10) | 0 |

| Hemodynamic Instability | 2801 (13.39) | 1908 (11.98) | 3 | 1560 (12.53) | 1536 (12.33) | 2 |

| History of a Cardiac Arrest | 2356 (11.26) | 1630 (10.24) | 0 | 1285 (10.32) | 1274 (10.23) | 0 |

| Prior CABG | 6197 (29.63) | 3540 (22.23) | 13 | 3239 (26.01) | 3173 (25.48) | 1 |

| Primary Valvular Heart Disease | 1892 (9.04) | 1369 (8.60) | 1 | 1122 (9.01) | 1087 (8.73) | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2982 (14.26) | 1652 (10.38) | 9 | 1491 (11.97) | 1455(11.68) | 1 |

| Lung disease | 3960 (18.93) | 2407 (15.12) | 7 | 2158 (17.33) | 2109(16.93) | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6992 (33.43) | 4493 (28.22) | 6 | 3961 (31.81) | 3887 (31.21) | 1 |

| Hypertension | 14571 (69.66) | 9580 (60.17) | 11 | 8219 (65.99) | 8154 (65.47) | 0 |

| Most Recent LVEF % | 33.80 (14.06) | 34.19 (14.69) | 3 | 33.72 (14.32) | 33.78 (14.27) | 0 |

| Hemoglobin | 13.25 (1.88) | 13.29 (1.96) | 2 | 13.28 (1.91) | 13.30 (1.94) | 1 |

| Sodium | 138.77 (4.05) | 138.53 (4.92) | 5 | 138.76 (3.57) | 138.55 (5.09) | 5 |

| Creatinine | 1.30 (1.05) | 1.26 (1.05) | 4 | 1.28 (1.06) | 1.28 (1.04) | 1 |

| Procedural Factors | ||||||

| Primary Prevention | 11178 (53.44) | 7455 (46.82) | 13 | 6473 (51.98) | 6446 (51.76) | 0 |

| Lead only | 3819 (18.26) | 4824 (30.30) | 29 | 2823 (22.67) | 2941 (23.61) | 2 |

| Routine coumadin therapy | 6591 (31.51) | 4414 (27.72) | 8 | 3650 (29.31) | 3636 (29.20) | 0 |

| Lead implant duration, yrs‡ | 6.52 (2.92) | 4.95 (3.08) | 52 | 5.73 (2.40) | 5.57 (2.92) | 6 |

| Single coil lead§ | 6363 (30.42) | 6579 (41.32) | 23 | 4482 (35.99) | 4536 (36.42) | 1 |

| Dual coil lead§ | 20128 (96.22) | 14348 (90.11) | 25 | 11847 (95.13) | 11823 (94.93) | 1 |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||||

| Teaching | 6129 (29.30) | 4183 (26.27) | 7 | 3503 (28.13) | 3477 (27.92) | 0 |

| Number of lead explantation in the hospital | 29.45 (54.44) | 101.54 (121.45) | 80 | 33.58 (61.04) | 94.44 (110.39) | 68 |

| Physician training | ||||||

| Board-certified EP | 15754 (75.31) | 12685 (79.67) | 10 | 9800 (78.69) | 9819 (78.84) | 0 |

Other baseline characteristics used in the propensity model included: history of syncope, family history of sudden death, prior myocardial infarction, prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), electrophysiology study, QRS duration, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, BUN (mean), potassium (mean), procedure type (initial generator vs generator change vs lead only), coumadin held for procedure, final device type (single chamber versus dual chamber versus cardiac resynchronization therapy), number of leads in the procedure, discharge medications (ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, aspirin, beta blocker, diuretic, and warfarin), hospital ownership (public vs private vs not-for-profit), hospital setting (division, micro, metro, rural), staffed hospital beds, hospital teaching status, ability to perform advanced cardiac procedures, and hospital geographic region.

ASD = absolute standardized difference defined as the absolute difference in means (or proportions) divided by the average standard deviation

NYHA categories do not add up to total due to some missingness

When more than one lead was present, the maximum lead implant duration was used

These groups are not mutually exclusive. Many subjects in this cohort had more than one indwelling ICD lead and the presence of any single coil or dual coil lead is reported here.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics with standardized difference before and after matching of the Medicare survival cohort.

| Description | Before Matching | After Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Abandonment[# (%) or mean (std)] | Lead Explantation[# (%) or mean (std)] | ASD* | Lead Abandonment[# (%) or mean (std)] | Lead Explantation[# (%) or mean (std)] | ASD | |

| All | 1239 (100) | 746 (100) | 588 (100.00) | 588 (100.00) | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, yrs | 76.25 (6.74) | 74.77 (5.97) | 23 | 75.30 (6.60) | 75.04 (5.94) | 4 |

| Gender: Female | 315 (25.42) | 196 (26.27) | 2 | 155 (26.36) | 150 (25.51) | 2 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1127 (90.96) | 670 (89.81) | 4 | 538 (91.50) | 533 (90.65) | 3 |

| Medical History | ||||||

| Heart Failure | 964 (77.80) | 582 (78.02) | 8 | 460 (78.23) | 464 (78.91) | 2 |

| NYHA Functional Classification† | ||||||

| - Class I | 193 (15.58) | 102 (13.67) | 5 | 82 (13.95) | 81 (13.78) | 0 |

| - Class II | 448 (36.16) | 262 (35.12) | 2 | 221 (37.59) | 215 (36.56) | 2 |

| - Class III | 525 (42.37) | 304 (40.75) | 3 | 234 (39.80) | 242 (41.16) | 3 |

| - Class IV | 23 (1.86) | 26 (3.49) | 11 | 17 (2.89) | 17 (2.89) | 0 |

| Non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy | 309(24.94) | 214 (28.69) | 11 | 155 (26.36) | 166 (28.23) | 5 |

| Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter | 547 (44.15) | 325 (43.57) | 2 | 254 (43.20) | 267 (45.41) | 5 |

| Ventricular Tachycardia | 604 (48.75) | 295 (39.54) | 16 | 254 (43.20) | 244 (41.50) | 3 |

| Hemodynamic Instability | 145 (11.70) | 74 (9.92) | 7 | 53 (9.01) | 57 (9.69) | 2 |

| History of a Cardiac Arrest | 133 (10.73) | 57 (7.64) | 10 | 51 (8.67) | 52 (8.84) | 1 |

| Prior CABG | 515 (41.57) | 283 (37.94) | 5 | 228 (38.78) | 231 (39.29) | 1 |

| Primary Valvular Heart Disease | 145 (11.70) | 101 (3.54) | 7 | 72 (12.24) | 71 (12.07) | 0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 205 (16.55) | 131 (17.56) | 5 | 92 (15.65) | 103 (17.52) | 5 |

| Lung disease | 275 (22.20) | 157 (21.05) | 1 | 119 (20.24) | 123 (20.92) | 2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 466 (37.61) | 281 (37.67) | 3 | 228 (38.78) | 227 (38.61) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 950 (76.67) | 557 (74.66) | 2 | 447 (76.02) | 444 (75.51) | 0 |

| Most Recent LVEF % | 33.56 (13.25) | 31.54 (12.96) | 15 | 32.11 (13.02) | 32.51 (13.43) | 3 |

| Hemoglobin | 13.06 (1.73) | 13.03 (1.84) | 2 | 13.06 (1.71) | 13.10 (1.84) | 2 |

| Sodium | 138.55 (4.83) | 138.68 (3.11) | 3 | 138.45 (6.16) | 138.69 (3.15) | 4 |

| Creatinine | 1.37 (0.90) | 1.36 (0.87) | 1 | 1.36 (1.01) | 1.35 (0.84) | 0 |

| Procedural Factors | ||||||

| Primary Prevention | 782 (63.12) | 472 (63.27) | 0 | 389 (66.16) | 375 (63.78) | 5 |

| Lead only | 96 (7.75) | 111 (14.88) | 23 | 62 (10.54) | 73 (12.41) | 6 |

| Routine coumadin therapy | 474 (38.26) | 276 (37.00) | 2 | 225 (38.27) | 226 (38.44) | 1 |

| Lead implant duration, yrs‡ | 5.45 (2.91) | 4.07 (2.18) | 52 | 4.49 (1.84) | 4.43 (2.09) | 3 |

| Single coil lead§ | 254 (20.50) | 195 (26.14) | 14 | 140 (23.81) | 133 (22.62) | 3 |

| Dual coil lead§ | 1196 (96.53) | 694 (93.03) | 16 | 563 (95.75) | 564 (95.92) | 1 |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||||

| Teaching | 402 (32.45) | 227 (30.43) | 4 | 187 (31.80) | 182 (30.95) | 2 |

| Number of lead explantations in the hospital | 30.25(55.97) | 99.55 (119.04) | 81 | 33.92 (64.85) | 91.45 (111.21) | 63 |

| Physician training | ||||||

| Board-certified EP | 931(75.14) | 611 (81.90) | 16 | 477 (81.12) | 473 (80.44) | 2 |

Other baseline characteristics used in the propensity model included: history of syncope, family history of sudden death, prior myocardial infarction, prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), electrophysiology study, QRS duration, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, BUN (mean), potassium (mean), procedure type (initial generator vs generator change vs lead only), coumadin held for procedure, final device type (single chamber versus dual chamber versus cardiac resynchronization therapy), number of leads in the procedure, discharge medications (ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, aspirin, beta blocker, diuretic, and warfarin), hospital ownership (public vs private vs not-for-profit), hospital setting (division, micro, metro, rural), staffed hospital beds, hospital teaching status, ability to perform advanced cardiac procedures, and hospital geographic region.

ASD = absolute standardized difference defined as the absolute difference in means (or proportions) divided by the average standard deviation

NYHA categories do not add up to total due to some missingness

When more than one lead was present, the maximum lead implant duration was used

These groups are not mutually exclusive. Many subjects in this cohort had more than one indwelling ICD lead and the presence of any single coil or dual coil lead is reported here.

Significant and important differences between the lead abandonment and explantation patients were expected in this non-randomized cohort. A preliminary examination of the data confirmed this. As such, a 1 to 1 matched-patient analysis was planned and performed according to the methods described by Rosenbaum and Rubin. 18 Briefly, a propensity model was built using logistic regression in which the dependent variable was an indicator of whether each patient was from the abandonment or explantation group, and the independent variables were baseline variables regarded as potentially clinically important. Independent variables included those listed in Tables 1 and 2. Of note, because we could not differentiate implant duration for the lead being revised from other indwelling leads, we included the maximum lead implant duration in our model. Missing values for the covariates were rare (<2%) except for ICD indication (24%) and final device type (24%), so these were imputed to the most common values for categorical variables and to the median for continuous variables in the model analyses. In addition, for the ICD indication and the final device type variables, dummy variables indicating the presence of a missing value was added into the model.

The number of patients in the lead abandonment group was larger than the lead explantation group, so patients were selected from the lead abandonment group to match those in the lead explantation group in a 1:1 ratio based on the propensity models. An estimated probability of being an explantation patient (propensity score) and a corresponding logit (loge[p/(1-p)]) were calculated for each patient. For a given explantation patient, all abandonment patients were considered whose logit differed from the explantation patient's logit by less than the caliper width (0.6 * standard deviation of the logit); among these patients, the abandonment patient with the closest logit from the explantation patient was selected as the match. Each abandonment patient was matched at most once for each analysis. Differences in procedural complications between the matched groups of patients were assessed using the chi-square test.

The matching process was repeated for the Medicare subgroup to obtain matched groups for a comparison of device related complications at six-months as well as mortality pre-discharge, at 90-days, and at one year. Unadjusted all-cause mortality event rates were summarized with Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Six-month complications were compared between groups using the chi-square statistic for categorical variables. Results were considered statistically significant when two-sided p<0.05. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the overall lead abandonment and explantation cohorts before and after matching are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Before matching in the NCDR cohort there were 36,840 patient encounters including 20,918 and 15,922 in the abandonment and explantation groups, respectively. Before matching in the Medicare cohort, there were 1,985 total patient encounters for the survival analysis (1,239 abandonment and 746 explantation) and 1,784 patient encounters for the 6-month complications analysis (1,121 abandonment and 663 explantation).

In all three of the analysis cohorts, compared with patients in the explantation group, those in the abandonment group were older, had a greater burden of comorbid conditions, were more likely to have a primary prevention ICD, and were treated at hospitals with less experience in lead explantation; facility and provider characteristics were similar for patients in the explantation and abandonment groups. Maximum lead implant duration was significantly longer in the abandonment group (6.5 versus 5.0 years in the overall cohort, 5.5 versus 4.1 years in the Medicare survival cohort, and 5.4 versus 4.1 years in the Medicare 6-month complications cohort). Severity of heart failure as measured by NYHA functional class and rates of important comorbidities including history of CABG surgery, lung disease and diabetes mellitus were similar between groups.

After matching, there were 24,908 patient encounters in the overall cohort matched 1:1 between abandonment and explantation; in the survival and 6-month complications Medicare cohorts, there were 1176 and 1042 patient encounters, respectively. Propensity score matching resulted in improved similarity between groups in all three analysis cohorts with the absolute standardized difference on all measured variables no greater than 8% except for center explantation volume which remained poorly matched (Tables 1 and 2). Notably, after matching in the overall cohort, lead implant duration averaged 5.7 and 5.6 years in the abandonment and explantation groups, respectively. In the matched Medicare survival and 6-month complication cohorts, lead implant duration was 4.5 and 4.4 years in abandonment and explantation groups, respectively.

As noted above, we were not able to exclude those explantation procedures involving simple traction techniques versus true extraction. However, only 7.2% of procedures in the overall cohort involved leads with a maximum lead implant duration of <1 year, and in many instances leads with a dwell time ≥ 1 year are more likely to be removed with extraction.

In-hospital complications

In-hospital complications were evaluated in the 1:1 matched overall cohort. In the lead abandonment group, 286 (2.30%) patients experienced an intra or post procedural event or death prior to discharge compared with 500 (4.01%) in the lead explantation group (p<0.001) (Table 3). Compared with abandonment patients, explantation patients were more likely to die (26 [0.21%] versus 80 [0.64%] deaths, respectively, p<0.001) and/or to experience a complication prior to discharge (273 [2.19%] versus 469 [3.77%] events, respectively, p<0.001). When examined by type of event, explantation patients were more likely to experience cardiac arrest, cardiac perforation, cardiac valve injury, hematoma requiring intervention, hemothorax, infection requiring antibiotics, lead dislodgement, pericardial tamponade, peripheral embolus, venous obstruction, and urgent cardiac surgery (p≤0.02 for all) (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference in the rate of drug reaction, conduction block, coronary venous dissection, myocardial infarction, pneumothorax, set screw problem, or stroke/TIA (p>0.05 for all), and the only complication that was numerically more common in the lead abandonment group was set screw problem (p=0.06). When examined by severity of event, major complications were experienced by 103 (0.83%) in the lead abandonment group and 227 (1.82%) in the lead explantation group (p<0.001). Minor complications occurred in 166 (1.33%) and 262 (2.10%) of patients, respectively (p=<0.001).

Table 3. In-Hospital Complications (Overall Population).

| Description | Lead Abandonment | Lead Explantation | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| # | % | # | % | ||

| N | 12454 | 100.00 | 12454 | 100.00 | -- |

| In-hospital death | 26 | 0.21 | 80 | 0.64 | 0.0000 |

| Death or Procedure Events | 286 | 2.30 | 500 | 4.01 | 0.0000 |

| Any Intra- or Post- Procedure Events | 273 | 2.19 | 469 | 3.77 | 0.0000 |

| Major complications | 103 | 0.83 | 227 | 1.82 | 0.0000 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 18 | 0.14 | 56 | 0.45 | 0.0000 |

| Cardiac Perforation | 10 | 0.08 | 54 | 0.43 | 0.0000 |

| Cardiac Valve Injury | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.02 | 0.0000 |

| Coronary Venous Dissection | 8 | 0.06 | 15 | 0.12 | 0.1444 |

| Hemothorax | 9 | 0.07 | 24 | 0.19 | 0.0090 |

| Pericardial Tamponade | 17 | 0.14 | 75 | 0.60 | 0.0000 |

| Pneumothorax | 48 | 0.39 | 49 | 0.39 | 0.9183 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 1 | 0.01 | 4 | 0.03 | 0.1797 |

| TIA or Stroke (CVA) | 4 | 0.03 | 7 | 0.06 | 0.3657 |

| Urgent Cardiac Surgery | 13 | 0.10 | 59 | 0.47 | 0.0000 |

| Minor complications | 166 | 1.33 | 262 | 2.10 | 0.0000 |

| Conduction Block | 1 | 0.01 | 6 | 0.05 | 0.0588 |

| Drug Reaction | 10 | 0.08 | 5 | 0.04 | 0.1967 |

| Hematoma Requiring Re-op, Evacuation or Transfusion | 42 | 0.34 | 67 | 0.54 | 0.0157 |

| Infection Requiring Antibiotics | 9 | 0.07 | 24 | 0.19 | 0.0090 |

| Lead Dislodgement | 96 | 0.77 | 138 | 1.11 | 0.0054 |

| Peripheral Embolus | 0 | 0.00 | 11 | 0.09 | 0.0000 |

| Set Screw Problem | 6 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.0588 |

| Venous Obstruction | 5 | 0.04 | 26 | 0.21 | 0.0002 |

In a logistic regression model performed on the matched overall cohort, the odds ratio (OR) of an explantation patient experiencing an in-hospital complication or death compared to an abandonment patient was 1.73 (95% CI 1.53-1.95, p<0.001). This OR was essentially unchanged after adjusting for demographic, medical history, procedural, hospital, and operator characteristics.

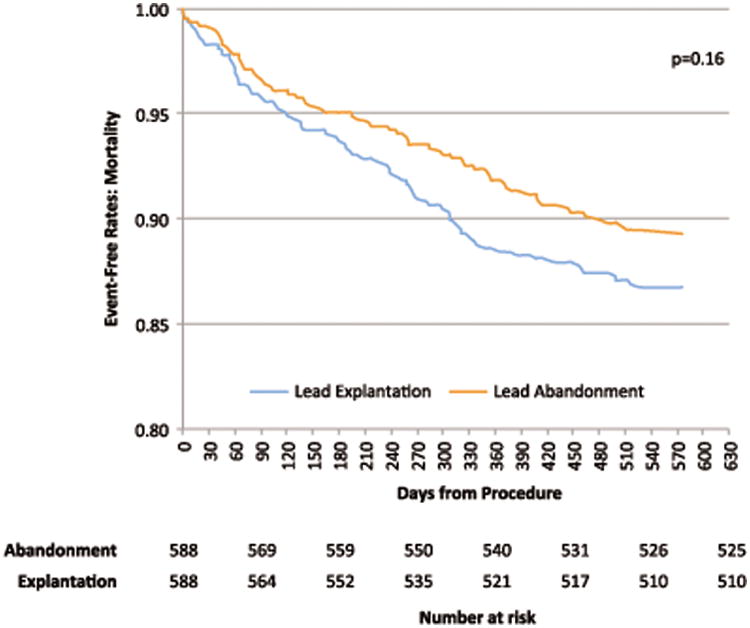

Mortality

Mortality risk was assessed in the 1:1 matched Medicare cohort. The mean follow up was approximately 14.7 months in both the lead abandonment and explantation groups. There was numerically greater mortality in the explantation group compared with the abandonment group at each time point assessed: in-hospital, 90 days post discharge, and one year post discharge (Table 4). There were only seven total in-hospital deaths in this cohort including 2 in the abandonment group and 5 in the explantation group (p=0.26). Within 90 days of discharge, there were 19 (3.23%) and 24 (4.08%) deaths (p=0.44), and within one year there were 48 (8.16%) and 67 (11.39%) deaths, p=0.06, respectively in the lead abandonment and explantation groups (Table 4). All-cause mortality is summarized with Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Figure 2 and demonstrates no statistically significant difference over the course of follow up (p=0.16).

Table 4. In hospital, 90 day, and one year mortality in lead abandonment and explantation Medicare patients.

| Description | Lead Abandonment N = 588 | Lead Explantation N = 588 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| # | % | # | % | ||

| Follow-up Months from Procedure for Death (mean, SD) | 14.7 | 4.2 | 14.7 | 4.7 | 0.91 |

| Survival Months from Procedure (mean, SD) | 7.5 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 4.9 | 0.42 |

| In-hospital death | 2 | 0.34 | 5 | 0.85 | 0.26 |

| Death within 90-days | 19 | 3.23 | 24 | 4.08 | 0.44 |

| Death within one year | 48 | 8.16 | 67 | 11.39 | 0.06 |

| Total death | 63 | 10.71 | 78 | 13.27 | 0.18 |

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Medicare patients undergoing lead abandonment versus explantation.

Six-month complications

There were 1042 subjects enrolled in Medicare at the time of the procedure and for the subsequent six months that could be matched 1:1 to assess differences in six-month complications occurring after discharge between lead abandonment versus explantation (Figure 1). There were no differences observed between groups in regard to bleeding, pericardial tamponade, infection requiring antibiotics, urgent surgery, upper extremity thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism at six months (p>0.05 for all) (Table 5) although event rates were low for most of these outcomes.

Table 5. Six-month complications from lead abandonment versus explantation in a Medicare subgroup following hospital discharge.

| Description | Lead Abandonment N=521 | Lead Explantation N=521 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| # | % | # | % | ||

| Bleeding | 25 | 4.80 | 25 | 4.80 | 1.0000 |

| Pericardial tamponade | 2 | 0.38 | 3 | 0.58 | 0.6539 |

| Infection | 7 | 1.34 | 16 | 3.07 | 0.0577 |

| Urgent surgery | 6 | 1.15 | 6 | 1.15 | 1.0000 |

| Upper extremity thrombosis | 4 | 0.77 | 5 | 0.96 | 0.7378 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 0.38 | 5 | 0.96 | 0.2552 |

Discussion

There are three major findings from our analysis of outcomes of patients undergoing lead revision of non-infected ICD leads from the NCDR ICD registry: First, procedural complications and death are very low but occur slightly more frequently in patients undergoing explantation compared with abandonment. Second, in the Medicare subgroup there was a trend towards greater mortality in the explantation group, but both groups had relatively high rates of 90 day and one year mortality with nearly one in ten patients dead within a year. Last, in Medicare patients, differences in complication rates including death in the year after hospital discharge were not significantly different for patients undergoing lead explantation versus abandonment.

Previous cohort studies and case series have found rates of periprocedural mortality from an unused/malfunctioning ICD lead extraction to be in the range of 0.3 to 0.6%. 10, 19 The in-hospital mortality rate in the overall cohort in our analysis was 0.64% in the explantation group and 0.21% in the abandonment group (p<0.001). In a Medicare subgroup, in-hospital mortality was 0.85% (explantation) and 0.34% (abandonment), but this was based on only 5 and 2 events, respectively (p=0.26).

Both lead management strategies studied here were associated with low procedural risk with 2.19% of abandonment patients in the overall cohort experiencing an in-hospital complication compared with 3.77% of explantation patients (p<0.001). This absolute difference of 1.58% corresponds to a number needed to harm of 63. T It is noteworthy that the time period studied (2010-2011) was one in which the Medtronic Sprint Fidelis (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) recall was underway. Indeed, a majority of revised leads in our analysis were manufactured by Medtronic, and the majority of leads were revised in response to an advisory or recall (Data Supplement). Explantation of the Sprint Fidelis lead by experienced operators is generally considered to be less complicated than explantation of other leads (e.g., Riata) 20, so the overall procedural risk observed in this cohort is likely conservative compared with contemporary experience. Moreover, actual or anticipated lead failures in the context of this recall may have encouraged lead revision of relatively young leads; average lead implant duration was approximately 5.5 years in all matched groups. Since lead implant duration is well known to correlate with lead explantation complications, this may also contribute to a conservative estimate of complications in the lead explantation cohorts.

Tear of the superior vena cava is an important and potentially lethal complication of lead explantation, but it is not captured in the NCDR ICD Registry. Instead, urgent cardiac surgery is considered a reasonable surrogate. Therefore, it is intriguing that the number of in-hospital deaths in the explantation group (80) exceeded the number of urgent cardiac surgeries (59). This is consistent with evidence in the literature. 10, 21, 22 There are three potential explanations for this finding. First, explantation procedures taking place outside the cardiothoracic operating room complicated by a vascular tear or cardiac avulsion may result in death before urgent surgery can be undertaken. In this case, urgent cardiac surgery is considered a reasonable surrogate for vascular tear since the latter complication is not captured in the ICD Registry. Second, complications more common in the explantation group (e.g., stroke) that do not require surgical intervention, may contribute substantially to the mortality rate, and third, those complications occurring at similar rates in explantation and abandonment patients (e.g., myocardial infarction) may be more deadly in explantation patients. As such, data on cause of death may help further explain this slight difference in mortality; however, these data are unavailable.

Following discharge, all-cause mortality to one year in the Medicare cohort was slightly higher in the explantation group compared with the abandonment group (8.16 compared with 11.39%, respectively (p=0.06)). While not statistically significant, the trend shows greater mortality in the explantation group with numerically more deaths at each time point measured (in hospital, 90 days post discharge, 1 year post discharge). The Medicare subgroup was more than 10 times smaller than the overall cohort and as a result had lower statistical power to identify mortality and safety differences between groups. However, the overall sample size represents the largest published cohort to date. . While the numerical difference in mortality between these groups of older patients appears to widen with increasing time (Figure 2), it remains unknown how outcomes would differ beyond one year. Even if a difference exists in outcomes beyond 1 year, it is unclear how much of this difference is due to differences in comorbidities that could not be captured from observational data (as compared with a randomized trial).

In other investigations of outcomes following sterile lead extraction, mortality was lower.10, 23, 24 For example, Maytin and colleagues reported outcomes of patients undergoing lead extraction at a single, high volume institution and found that among patients with extraction of sterile leads, one year mortality was 8.4%. 24 However, our clinical practice cohort was older (mean 75 years vs 56 years)25, had a higher burden of comorbid illness especially diabetes, and a greater range of center and provider volume which are known to make a difference in outcomes. 26

The one-year mortality rate for patients undergoing lead abandonment in this analysis was relatively high despite low rates of ICD-related complications (Table 5). Interestingly, this mortality rate as well as the mortality rate in the explantation group are similar to that seen in an all-comer NCDR ICD Registry cohort undergoing elective generator replacement in which a 9.8% one year mortality was observed and only 6.2% of subjects underwent concomitant lead revision. 27 This suggests that in clinical practice, lead revision decisions are often made in older patients with multiple comorbidities such that the risk of any procedure increases with increasing comorbidity burden and competing risks of death. Indeed, choosing a revision strategy involves complex decision making. For example, in our pre-matched cohorts, maximum lead implant duration was significantly longer in abandonment patients compared with explantation patients that likely reflects health care providers' awareness that longer implant duration increases the risks of explantation. While this difference was balanced with propensity-matching, other differences between groups may be less well captured in the Registry.

In order to assess outcomes beyond the index hospitalization, we had to limit our cohort to those patients enrolled in Medicare. In this subgroup, we assessed complications within six months of hospital discharge, and found no difference between the explantation and abandonment groups for any outcome. This means that while there were differences in the overall cohort between groups in regard to infection, tamponade, venous obstruction, and urgent surgery prior to discharge, there were no differences seen at six months in these outcomes in the Medicare subgroup. Notably, complications from lead abandonment are more difficult to capture than those from explantation especially from claims data in which some outcomes (e.g., asymptomatic venous occlusion) may not be captured. Moreover, whether they are captured in claims data or not, complications from lead abandonment may be expected to accrue over a much longer time period than one year. Thus, longer term complications of abandonment may be more relevant in a younger cohort in whom leads that may someday need extraction are left to dwell longer as comorbidities and age accumulate. Indeed, investigators reporting on the experience of young patients with abandoned leads concluded that abandonment may simply postpone inevitable lead extraction. 28

Based on these results, and consistent with previous work, while lead explantation is a riskier procedure in the short term, both lead explantation and lead abandonment are associated with relatively few deaths and complications. At one year, explantation does not appear to provide benefit over lead abandonment in a Medicare population.

Limitations

The decision to explant or abandon an unused/malfunctioning ICD lead involves numerous considerations many of which are not included in our analysis: perceived surgical risk, life expectancy, and patient preferences to name a few. In addition, outcomes in our analysis were limited to those in the ICD Registry and in the CMS administrative database; other outcomes (e.g., asymptomatic venous occlusion), intermediate term outcomes in non-Medicare patients, and outcomes outside of the 2010-2011 window during which the Sprint Fidelis lead recall was underway were not available, and so our results may not apply to all patients or more current procedures or leads. We used propensity score matching by including an extensive list of clinically relevant variables in order to reduce the bias of healthier patients undergoing lead explantation; this process leaves some patients unmatched, so our results may not apply to patients with the highest level of comorbidity burden or other outlier characteristics. In particular, we were unable to match well on the variable of center explantation volume (absolute standard difference >60%) such that patients undergoing explantation were treated in centers with a much greater average number of explants per year which has two potential implications: (1) these findings may underestimate complication rates at centers with lower explantation volume and (2) this may represent a referral bias; patients undergoing explantation may have more commonly been referred to an explantation center specifically for explantation making their revision strategy “pre-determined”. In addition, propensity score matching cannot account for every clinical scenario, so the differences in outcomes between lead abandonment and lead explantation patients in our analysis may not apply to all “propensity matchable” patients. For example, while we matched patients based on long term warfarin usage to account for risks of procedural bleeding, this does not take into account how perceived risks of warfarin discontinuation influenced lead revision decisions, and while procedural bleeds associated with warfarin continuation through a procedure would be well captured in this analysis, embolic strokes occurring after discharge would not be. Finally, we could not exclude explantation procedures involving simple traction techniques versus true extraction. Although the number of procedures (7.2%) involving leads with dwell time < 1 year is too small to have a large impact on the overall outcomes, it should be acknowledged that some leads with dwell time ≥ 1 year can be removed with simple traction and as a result, 7.2% likely underestimates the true number of leads that were removed with simple traction.

Clinical Implications

In this study, management of unused/malfunctioning ICD leads was associated with <1% in-hospital mortality and <5% overall in-hospital complications regardless of the adopted strategy. Following hospitalization for lead management, mortality was somewhat higher at discharge, 90 days, and one year, among Medicare-aged patients undergoing explantation vs abandonment, but 6-month device-related complications appeared to be similar between the 2 groups. Future longitudinal studies will hopefully provide better understanding of the longer term outcomes of lead abandonment and explantation, especially in younger patients. However, only adequately-powered randomized prospective trials with long-term follow-up can provide the most meaningful guidance to patients and physicians facing the decision to abandon or explant an unused or malfunctioning lead.

Supplementary Material

What is Known.

Patients with an unused/malfunctioning implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) lead undergoing revision may have the unused/malfunctioning lead either abandoned or explanted.

ICD leads are revised based on weighing upfront risks of explantation against later risks of lead abandonment, but comparative safety data between these two revision strategies are limited.

What the Study Adds.

Compared with lead abandonment, patients undergoing lead explantation of an unused/malfunctioning ICD lead had slightly higher in-hospital complications and deaths.

One year after lead revision in a Medicare population, mortality risk was higher in lead the explantation patients compared with abandonment patients, but the difference did not meet statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Sean Pokorney, MD MBA, for his tremendously helpful assistance in collecting and confirming lead characteristics.

Funding Sources: This research was supported by the American College of Cardiology's National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR). The views expressed in this manuscript represent those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCDR or its associated professional societies identified at CVQuality.ACC.org/NCDR.

Disclosures: Dr. Zeitler was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) T-32 training grant #2 T32 HL 69749-11 A1. Dr. Dharmarajan is supported by grant K23AG048331-02 from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. However, no relationships exist related to the analysis presented. Drs Al-Khatib, Anstrom, Curtis, and Peterson report no relevant disclosures. Dr. Daubert reports modest honoraria from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical; moderate to significant research grant and fellowship support to his institution from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and Medtronic.

References

- 1.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial I. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1882–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadish A, Dyer A, Daubert JP, Quigg R, Estes NA, Anderson KP, Calkins H, Hoch D, Goldberger J, Shalaby A, Sanders WE, Schaechter A, Levine JH Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation I. Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2151–2158. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial III. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mond HG, Proclemer A. The 11th world survey of cardiac pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: calendar year 2009--a World Society of Arrhythmia's project. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:1013–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voigt A, Shalaby A, Saba S. Continued rise in rates of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections in the United States: temporal trends and causative insights. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:414–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Byrd CL, Bongiorni MG, Carrillo RG, Crossley GH, 3rd, Epstein LM, Friedman RA, Kennergren CE, Mitkowski P, Schaerf RH, Wazni OM Heart Rhythm Society; American Heart Association. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management: this document was endorsed by the American Heart Association (AHA) Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1085–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glikson M, Suleiman M, Luria DM, Martin ML, Hodge DO, Shen WK, Bradley DJ, Munger TM, Rea RF, Hayes DL, Hammill SC, Friedman PA. Do abandoned leads pose risk to implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patients? Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott PA, Chungh A, Zeb M, Yue AM, Roberts PR, Morgan JM. Is the use of an additional pace/sense lead the optimal strategy for the avoidance of lead extraction in defibrillation lead failure? A single-centre experience. Europace. 2010;12:522–526. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wazni O, Epstein LM, Carrillo RG, Love C, Adler SW, Riggio DW, Karim SS, Bashir J, Greenspon AJ, DiMarco JP, Cooper JM, Onufer JR, Ellenbogen KA, Kutalek SP, Dentry-Mabry S, Ervin CM, Wilkoff BL. Lead extraction in the contemporary setting: the LExICon study: an observational retrospective study of consecutive laser lead extractions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wollmann CG, Bocker D, Loher A, Kobe J, Scheld HH, Breithardt GE, Gradaus R. Incidence of complications in patients with implantable cardioverter/defibrillator who receive additional transvenous pace/sense leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:795–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amelot M, Foucault A, Scanu P, Gomes S, Champ-Rigot L, Pellissier A, Milliez P. Comparison of outcomes in patients with abandoned versus extracted implantable cardioverter defibrillator leads. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;104:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bode F, Himmel F, Reppel M, Mortensen K, Schunkert H, Wiegand UK. Should all dysfunctional high-voltage leads be extracted? Results of a single-centre long-term registry. Europace. 2012;14:1764–1770. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollmann CG, Bocker D, Loher A, Paul M, Scheld HH, Breithardt G, Gradaus R. Two different therapeutic strategies in ICD lead defects: additional combined lead versus replacement of the lead. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1172–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rijal S, Shah RU, Saba S. Extracting versus abandoning sterile pacemaker and defibrillator leads. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1107–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masoudi FA, Ponirakis A, Yeh RW, Maddox TM, Beachy J, Casale PN, Curtis JP, De Lemos J, Fonarow G, Heidenreich P, Koutras C, Kremers M, Messenger J, Moussa I, Oetgen WJ, Roe MT, Rosenfield K, Shields TP, Jr, Spertus JA, Wei J, White C, Young CH, Rumsfeld JS. Cardiovascular care facts: a report from the national cardiovascular data registry: 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1931–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman JV, Wang Y, Curtis JP, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA. Physician procedure volume and complications of cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. Circulation. 2012;125:57–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.046995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The bias due to incomplete matching. Biometrics. 1985;41:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunner MP, Cronin EM, Duarte VE, Yu C, Tarakji KG, Martin DO, Callahan T, Cantillon DJ, Niebauer MJ, Saliba WI, Kanj M, Wazni O, Baranowski B, Wilkoff BL. Clinical predictors of adverse patient outcomes in an experience of more than 5000 chronic endovascular pacemaker and defibrillator lead extractions. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bongiorni MG, Di Cori A, Segreti L, Zucchelli G, Viani S, Paperini L, De Lucia R, Levorato D, Boem A, Soldati E. Transvenous extraction profile of Riata leads: procedural outcomes and technical complexity of mechanical removal. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauser RG, Katsiyiannis WT, Gornick CC, Almquist AK, Kallinen LM. Deaths and cardiovascular injuries due to device-assisted implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and pacemaker lead extraction. Europace. 2010;12:395–401. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunner MP, Cronin EM, Wazni O, Baranowski B, Saliba WI, Sabik JF, Lindsay BD, Wilkoff BL, Tarakji KG. Outcomes of patients requiring emergent surgical or endovascular intervention for catastrophic complications during transvenous lead extraction. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunner MP, Cronin EM, Jacob J, Duarte VE, Tarakji KG, Martin DO, Callahan T, Borek PP, Cantillon DJ, Niebauer MJ, Saliba WI, Kanj M, Wazni O, Baranowski B, Wilkoff BL. Transvenous extraction of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads under advisory--a comparison of Riata, Sprint Fidelis, and non-recalled implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1444–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maytin M, Jones SO, Epstein LM. Long-term mortality after transvenous lead extraction. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:252–257. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.965277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams SE, Arujuna A, Whitaker J, Sohal M, Shetty AK, Roy D, Bostock J, Cooklin M, Gill J, O'Neill M, Wright M, Patel N, Bucknall C, Hamid S, Rinaldi CA. Percutaneous extraction of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) in octogenarians. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:841–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Monaco A, Pelargonio G, Narducci ML, Manzoli L, Boccia S, Flacco ME, Capasso L, Barone L, Perna F, Bencardino G, Rio T, Leo M, Di Biase L, Santangeli P, Natale A, Rebuzzi AG, Crea F. Safety of transvenous lead extraction according to centre volume: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2014;16:1496–1507. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer DB, Kennedy KF, Noseworthy PA, Buxton AE, Josephson ME, Normand SL, Spertus JA, Zimetbaum PJ, Reynolds MR, Mitchell SL. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving new and replacement implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results from the NCDR. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:488–497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvetti MS, Drago F. Outcome of young patients with abandoned, nonfunctional endocardial leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:473–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messenger JC, Ho KK, Young CH, Slattery LE, Draoui JC, Curtis JP, Dehmer GJ, Grover FL, Mirro MJ, Reynolds MR, Rokos IC, Spertus JA, Wang TY, Winston SA, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA NCDR Science and Quality Oversight Committee Data Quality Workgroup. The National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) data quality brief: The NCDR data quality program in 2012. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1484–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.