Abstract

We previously isolated an IL-11–mimic motif (CGRRAGGSC) that binds to IL-11 receptor (IL-11R) in vitro and accumulates in IL-11R–expressing tumors in vivo. This synthetic peptide ligand was used as a tumor-targeting moiety in the rational design of BMTP-11, which is a drug candidate in clinical trials. Here, we investigated the specificity and accessibility of IL-11R as a target and the efficacy of BMTP-11 as a ligand-targeted drug in lung cancer. We observed high IL-11R expression levels in a large cohort of patients (n = 368). In matching surgical specimens (i.e., paired tumors and nonmalignant tissues), the cytoplasmic levels of IL-11R in tumor areas were significantly higher than in nonmalignant tissues (n = 36; P = 0.003). Notably, marked overexpression of IL-11R was observed in both tumor epithelial and vascular endothelial cell membranes (n = 301; P < 0.0001). BMTP-11 induced in vitro cell death in a representative panel of human lung cancer cell lines. BMTP-11 treatment attenuated the growth of subcutaneous xenografts and reduced the number of pulmonary tumors after tail vein injection of human lung cancer cells in mice. Our findings validate BMTP-11 as a pharmacologic candidate drug in preclinical models of lung cancer and patient-derived tumors. Moreover, the high expression level in patients with non-small cell lung cancer is a promising feature for potential translational applications.

Lung cancer is the most common malignant tumor worldwide and the leading cause of death for both men and women.1, 2, 3, 4 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the most diffuse type of lung carcinoma, is only modestly responsive to chemotherapy and is therefore generally treated by surgical resection, if possible, at least for early clinical stages. Although cytotoxic combination chemotherapy is still used in advanced and metastatic stage and as neo-adjuvant or adjuvant treatment of earlier stages, target therapies have been increasingly used in NSCLC toward personalized treatments.5 Large randomized clinical trials demonstrated a benefit from the introduction of the antiangiogenic drug bevacizumab in combination therapy,6 as well as cetuximab in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor–expressing tumors.7, 8 Furthermore, small-molecule inhibitors, such as gefitinib9 or crizotinib,10 are options for NSCLC patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations or echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4–anaplastic lymphoma kinase translocations, respectively. However, despite improvements in therapeutic approaches, the survival expectation for patients with advanced NSCLC remains only 16 to 24 months.1 Thus, given the high incidence and rate of mortality associated with this tumor, new molecular targets are an unmet need.

Through the selection of circulating combinatorial phage display libraries in a terminal wean patient with cancer, we have uncovered new tumor- and vascular-specific molecular targets.11, 12, 13 Among these, the cyclic peptide motif CGRRAGGSC (single letter code) was validated as a mimic of IL-11, mapping to a previously unrecognized binding site that interacts with IL-11 receptor (IL-11R) with consequent STAT-3 phosphorylation and cell proliferation.14, 15 In addition to our previous work demonstrating elevated levels of IL-11R in prostate cancer,11 similar data have been reported in carcinomas of the breast, colon, and stomach; bone sarcomas; and leukemia/lymphomas.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 In preclinical models, the CGRRAGGSC peptide conjugated to a proapoptotic moiety (CGRRAGGSC-GG-D[KLAKLAK]2) selectively targeted prostate cancer osteoblastic metastasis, as well as osteosarcoma metastasis in the lung, while having no toxic effect on normal surrounding tissues.16, 21 This formulation, termed BMTP-11, underwent evaluation in a first-in-man phase zero clinical trial, aimed at defining drug specificity, maximum tolerated dose, and limiting toxicities with promising pilot results.22

Here, we evaluate IL-11R as a molecular target in human lung cancer and propose a therapeutic approach based on the selective targeting of IL-11R. In human samples, we found increased expression of IL-11R in tumors compared with adjacent nonmalignant tissues. Overexpressed IL-11R was exposed on the tumor cell membrane and was present also in tumor vascular endothelial cells, supporting the ligand-directed accessibility of this receptor from the circulation. We demonstrated that in vitro BMTP-11 efficiently targets and kills a panel of lung cancer cell lines derived from adenocarcinoma (ADC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), or large cell lung carcinoma. When BMTP-11 was systemically administered in vivo, we observed a significant delay in the growth of subcutaneous tumor xenografts plus a reduction in the establishment of pulmonary tumors after tail vein injection of human lung cancer cells. Taken together, these results suggest that BMTP-11 could potentially serve as an active targeted drug candidate to be evaluated in patients with lung cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The human lung cancer cell lines A549, H226, H460, and H522 were from the ATCC (Manassas, VA); HOP62 and HOP92 were from the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research cell repository (Bethesda, MD). Cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 5 mmol/L l-glutamine, and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin G and 100 mg/mL streptomycin; ThermoFisher Scientific).

Flow Cytometry

Exponentially growing cells were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in ice-cold PBS that contained 1% bovine serum albumin. Human Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) was added to each cell suspension (20 μL per 1 × 107 cells) and incubated for 10 minutes on ice. Next, 20 μL of either anti-human IL-11Rα-phycoerythrin–labeled antibody (Clone N-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) or phycoerythrin-conjugated rabbit IgG isotype control (GeneTex, Irvine, CA) was added per 1 × 106 cells in 100 μL of PBS that contained 1% bovine serum albumin and incubated at 4°C for 1 hour. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS that contained 1% bovine serum albumin and analyzed with a BD FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Cell Viability and Apoptosis Assays

Cells were grown to 95% confluence in 96-well plates (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Serial molar concentrations of either BMTP-11 or nontargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 control were added to each well to a final molar concentration of 1 to 1000 μmol/L. After incubation at 37°C for 18 hours, cell viability was assessed with the WST-1 assay (Roche Life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN). Values obtained in test conditions were normalized to negative controls and were expressed as percentage values. Apoptotic cell death was evaluated with the Annexin V/PI kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In essence, 15,000 cells were seeded into 96-well plates, treated with serial molar concentrations of either peptide (1 to 1000 μmol/L) for 6 hours, followed by the addition of 4 μL/well of the Annexin V antibody. Fluorescence was quantified in a ClarioStar plate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany). For both assays, reverse sigmoidal dose–response curves with variable slopes were fitted, and concentration that inhibits 50% (IC50) values were calculated with the Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Lung Cancer Mouse Models

Female nude BALB/c mice were from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). The H460 human lung cancer cell line is a well-established model, known to produce consistent subcutaneous tumors and lung tumors after intravenous administration. A subcutaneous model was obtained by implantation of 106 H460 cells into the flank; expression of IL-11R in these tumors was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Treatment consisted of injections of 10 mg/kg of either BMTP-11 or nontargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 peptide (n = 10 per group) at days 3 and 10 after tumor implantation. Tumor sizes were serially measured with a digital caliper, and tumor volumes were calculated.23, 24 A lung colonization model was established by tail vein injection of 106 H460 cells.25, 26, 27 Again, expression of IL-11R was confirmed in lung tumors by IHC staining with an anti–IL-11R antibody. Mice were treated with BMTP-11 (n = 10) or nontargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 peptide (n = 9) as described above in this section and sacrificed 15 days after tumor cell injection. Lungs were recovered, weighed on a digital scale, formalin-fixed, and paraffin-embedded. Ten sections corresponding to different levels of the lungs were obtained, which were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The number of tumors in each slide was determined by a pathologist. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and all experiments were completed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Patient-Derived Samples

The retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Surgical lung cancer specimens were obtained from the Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence Tissue Bank. A panel of patient-derived samples (n = 368) was collected from 1997 to 2001. A tissue microarray was constructed from triplicate 1-mm–diameter cores, punctured from central, intermediate, and peripheral regions of primary lung cancers (n = 327), as described.28, 29

IHC Staining

IHC was performed on 4-μm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Antigen retrieval was achieved by heating in 1 mmol/L EDTA pH 8.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific), followed by blocking in 3% H2O2 for 15 minutes and Protein Block Solution (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA; Code X0909) for 30 minutes. The primary goat anti-human (clone K20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; used for human tissues) or rabbit (clone C20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; used for mouse tissues) anti–IL-11Rα antibody was incubated for 2 hours. Staining was revealed with a secondary antibody and Envision Plus Dual Link-labeled polymer (Dako Corp.) for 30 minutes, after which time diaminobenzidine was applied for 5 minutes. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. IL-11R expression was evaluated by two independent expert pathologists as described.21, 30 Cytoplasmic scores were obtained by multiplying a 4-value intensity score (0, none; 1+, weak; 2+, moderate; 3+, strong) by the percentage of positive area. The membrane expression of IL-11R was quantified as percentage of membrane-positive cells over a total of at least 200 cells evaluated (Supplemental Table S1).

Statistical Analysis

To analyze IHC data, Wilcoxon signed rank tests were conducted to compare expressions of IL-11R in tumor specimens with nonmalignant bronchial epithelium. Linear regression models for continuous variables assuming a normal distribution and logistic regression models for binary variables were used to study the association of IL-11R expression with histology for all of the cohort patients. For patients with NSCLC (n = 301), either linear regression models or logistic regression models were built to characterize the association between IL-11R expression and clinical factors, including tumor pathology and smoking history. Regression analyses of survival data based on the Cox proportional hazards model were conducted on overall survival, defined as time from surgery to death or to the end of the study. The Student's t-test was applied to analyze all of the other data. All of the statistical tests were two-sided. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with the Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

IL-11R Is a Molecular Target in Human NSCLC

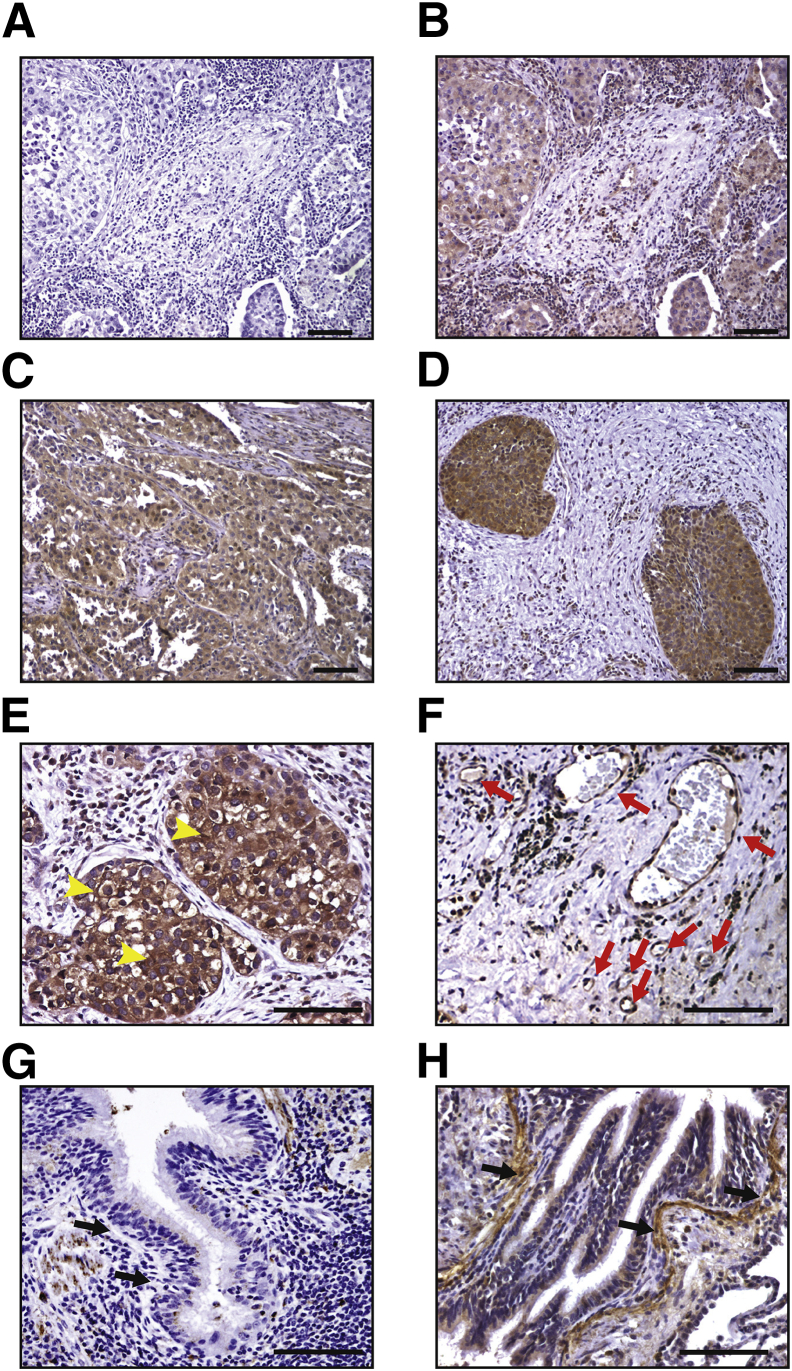

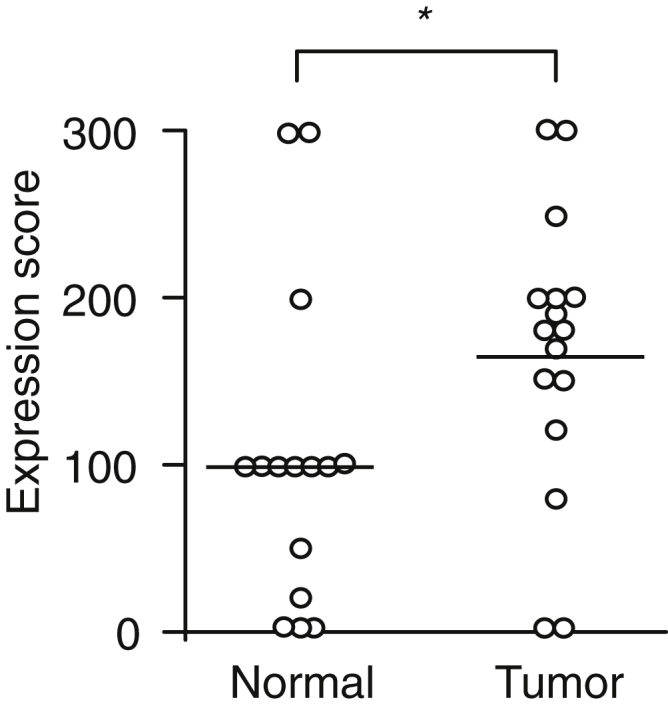

To begin to define the feasibility of a BMTP-11–based therapy in human lung cancer, we first examined the expression of IL-11R in a panel (n = 41) of primary formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumors by IHC with a specific anti–IL-11Rα antibody. This analysis revealed high cytoplasmic positivity in both SCC (Figure 1, A–C) and ADC (Figure 1D). In samples with grade 3+ cytoplasmic positivity, we also observed membrane IL-11R staining and grade 3+ positivity in blood vessels into the tumor stroma (Figure 1, E and F). For a subset of patient-derived samples (n = 18), matching nonmalignant lung tissues were also available; the expression of IL-11R in these tumor-adjacent lung tissues was comparable with that in lung tissue from a healthy donor (Figure 1G), except for a specific region corresponding to the bronchiolar wall below the basement membrane (Figure 1H). Cytoplasmic IL-11R levels were quantified and compared between tumor and nonmalignant tissues (Figure 2), confirming the observed higher expression in tumor cells (P = 0.003).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical validation of IL-11R in human lung cancer. A–D: Negative control (secondary antibody) (A), grade 2+ (B), and grade 3+ (C) cytoplasmic IL-11R staining in an exemplary SCC sample; grade 3+ cytoplasmic IL-11R staining in an exemplary adenocarcinoma (ADC) sample (D). E and F: Membrane positivity (arrowheads) and stromal blood vessel staining (F) in a representative ADC sample (arrows). G and H: Normal lung from a healthy donor (G) and a lung cancer patient (nonmalignant tissue adjacent to the tumor; H), arrows indicate the bronchiolar wall below the basement membrane. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 2.

IL-11R expression scores in tumor and adjacent nonmalignant tissue. Comparison of the cytoplasm expression scores between lung cancer and matched adjacent nonmalignant bronchial epithelium. n = 18 lung cancer samples; n = 18 nonmalignant bronchial epithelium samples. *P < 0.01.

These promising results prompted us to extend the analysis to a larger panel of lung cancer tissue microarray specimens (pilot, n = 327) (Table 1, Supplemental Table S1). In this cohort of patients, the cytoplasmic levels of IL-11R were significantly higher in NSCLC than in SCLC (ADC or SCC versus SCLC, P < 0.0001) (Table 2). The successive analyses were therefore focused exclusively on NSCLC samples (n = 301). The presence of IL-11R on the cell membrane was evaluated in 200 cells/tissue sections, revealing well-detectable positivity in approximately 25% of the cases. These same samples also exhibited higher cytoplasmic levels of IL-11R (P < 0.0001) (Table 3), suggesting that increased overall expression of IL-11R favors its allocation to the plasma membrane, where it can be targeted by ligand-directed therapeutic agents (such as BMTP-11). Then, to determine whether a subset of patients would specifically benefit from BMTP-11 therapy, we first assessed IL-11R expression in association to specific clinicopathologic features. This analysis revealed that patients with ADC had higher cytoplasmic levels of IL-11R than patients with SCC (P < 0.0001), and patients who had ever smoked (either former or current) had higher cytoplasmic levels of IL-11R than patients who never smoked (P = 0.005) (Table 3). These findings encourage the use of increased expression of IL-11R as a biomarker to identify patients who might benefit from IL-11R–targeted therapy.

Table 1.

Multivariate Analysis for Patients Included in the TMA

| Characteristic | Frequency count | Total frequency, % |

|---|---|---|

| Histology | ||

| ADC | 192 | 58.72 |

| SCLC | 26 | 7.95 |

| SCC | 109 | 33.33 |

| Sex | ||

| NA | 26 | 7.95 |

| Female | 162 | 49.54 |

| Male | 139 | 42.51 |

| Race | ||

| NA | 26 | 7.95 |

| Caucasian | 265 | 81.04 |

| Other | 36 | 11.01 |

| Type of smoker | ||

| NA | 26 | 7.95 |

| Current | 82 | 25.08 |

| Former | 120 | 36.70 |

| Never | 97 | 29.66 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.61 |

| Pathologic M | ||

| NA | 26 | 7.95 |

| M0 | 295 | 90.21 |

| M1 | 6 | 1.83 |

| Pathologic N | ||

| NA | 26 | 7.95 |

| N0 | 212 | 64.83 |

| N1 | 55 | 16.82 |

| N2 | 34 | 10.40 |

| Pathologic T | ||

| NA | 26 | 7.95 |

| T1 | 114 | 34.86 |

| T2 | 160 | 48.93 |

| T3 | 16 | 4.89 |

| T4 | 11 | 3.36 |

ADC, adenocarcinoma; NA, not analyzed (low target expression); SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; TMA, tissue microarray.

Table 2.

Correlation of IL-11R Cytoplasmic Expression with Tumor Histology

| Variable | DF | Estimate | SEM | Wald 95% confidence limits |

χ2 | P > χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 1 | 109.7222 | 13.6401 | 82.9880 | 136.4564 | 64.71 | <0.001 |

| Histology | |||||||

| ADC | 1 | 24.0349 | 14.3245 | −4.0405 | 52.1104 | 2.82 | 0.0934 |

| SCC | 1 | 6.6667 | 14.7330 | −22.2096 | 35.5429 | 0.20 | 0.6509 |

| SCLC | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| Scale | 1 | 57.8702 | 2.3586 | 53.4273 | 62.6827 | ||

ADC, adenocarcinoma; DF, degrees of freedom; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

Table 3.

Associations between IL-11R Expression and Tumor Clinicopathologic Features

| Source | DF | χ2 | P > χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-11R localization | 1 | 23.56 | <0.001 |

| Histology | 1 | 15.62 | <0.001 |

| Type of smoker | 2 | 10.49 | 0.0053 |

DF, degrees of freedom.

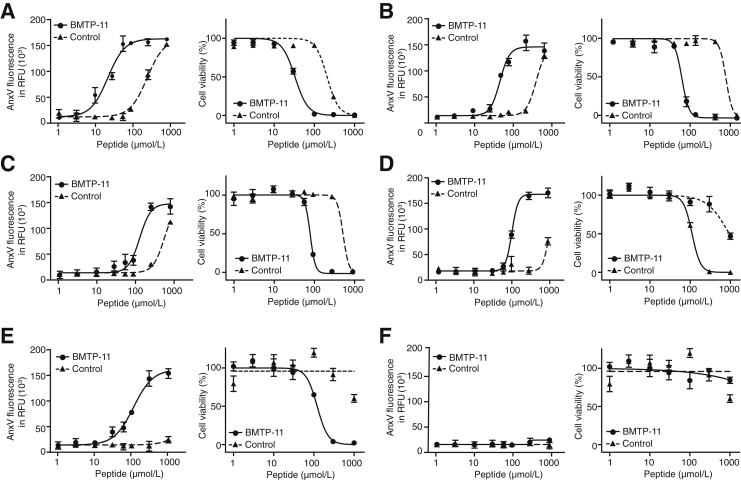

BMTP-11 Is Pharmacologically Active against Human Lung Cancer Cells in Vitro

Having determined the pathologic presence of IL-11R as a molecular target in lung cancer, we next evaluated the activity of BMTP-11 as a ligand-directed therapy in tissue culture and preclinical mouse models. We used the human lung cancer-derived cell lines A549, H226, H460, HOP62, and HOP92. All these NSCLC lines express IL-11R on their cell surface membranes as evaluated by flow cytometry (Table 4). H522 cells were used as a negative control, showing undetectable surface expression of IL-11R. Cultured cells were treated with serial concentrations of BMTP-11 or untargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 (control), followed by evaluation of both viability (by WST-1 assay at 18 hours after treatment) and apoptosis (by Annexin V/PI assay at 6 hours after treatment). Plots were fitted to reverse sigmoidal dose-response curves, showing that BMTP-11 reduced cell viability by inducing apoptosis in all tumor cell lines examined (Figure 3, A–E). H460 (Figure 3A), HOP62 (Figure 3B), and HOP92 (Figure 3C) cells exhibited almost no residual viability when treated with 100 μmol/L BMTP-11, while retaining approximately 100% viability in the presence of equimolar amounts of the control peptide (P < 10−8). Similar results were obtained with H226 (Figure 3D) and A549 (Figure 3E) cells at higher BMTP-11 concentrations (100 to 300 μmol/L). No effect was observed in the IL-11R− cell line H522 (Figure 3F). In all other tumor cell lines examined, the IC50 for BMTP-11 was 6.3- to 11.5-fold lower than the control (Table 5). These results show that BMTP-11 is active against IL-11R–expressing human lung cancer cells in vitro, with the advantage of suitable dose range, wide therapeutic window, and broad applicability in cells derived from different lung cancer types.

Table 4.

Membrane Expression of IL-11R in Human Lung Cancer Cell Lines

| Cell lines | IL-11R+ cells, % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Anti-human IL-11R | Control Ab | |

| H460 | 10.3 | 0.3 |

| HOP62 | 2.2 | 0.3 |

| HOP92 | 3.4 | 0.3 |

| H226 | 20.6 | 0.4 |

| A549 | 12.2 | 0.3 |

| H522 | 0.0 | 0.3 |

Ab, antibody.

Figure 3.

In vitro pharmacologic activity of BMTP-11 on lung cancer cell lines. Cells were treated with serial molar concentrations of BMTP-11 or nontargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 peptide (control). A–F: Viability was assessed by WST-1 assay at 18 hours after treatments (right panels). Apoptosis was evaluated by Annexin V staining at 6 hours after treatments (left panels). Reverse sigmoidal curves in logarithmic scale for H460 (A), HOP62 (B), HOP92 (C), H226 (D), A549 (E), and H522 (F) treated with BMTP-11 or control. RFU, relative fluorescence unit.

Table 5.

Derived IC50 Values for Cell Viability and Relative Efficacy

| Cell lines | IC50 (μmol/L) |

Relative efficacy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMTP-11 | D(KLAKLAK)2 | ||

| H460 | 33 | 208 | 6.3 |

| HOP62 | 47 | 544 | 11.5 |

| HOP92 | 83 | 572 | 6.9 |

| H226 | 111 | 936 | 8.4 |

| A549 | 120 | >1000 | >8.3 |

| H522 | 972 | >1000 | ∼1.1 |

IC50, concentration that inhibits 50%.

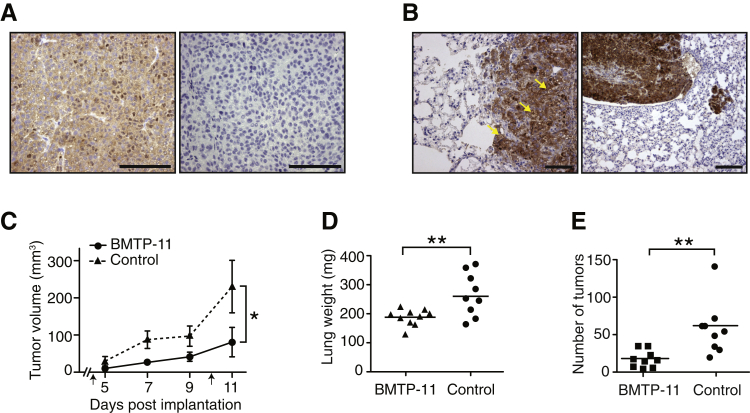

BMTP-11 Inhibits Tumor Growth in Vivo

To evaluate whether BMTP-11 can target tumors and exert antitumor activity in vivo, we set up two preclinical models, obtained by injection of H460 cells into the flank (subcutaneous xenograft) or through the tail vein (lung colonization model) of immunodeficient mice. The expression of IL-11R was assessed by IHC, confirming, in both models, the high levels observed in clinical samples (Figure 4, A and B) and the presence on the cell surface (Figure 4B). We administered systemic BMTP-11 treatment to subcutaneous tumor xenograft-bearing mice, followed by evaluation of tumor volumes. The therapeutic effect of BMTP-11 was tested on two cohorts of mice randomized in the following treatment groups: BMTP-11 (n = 10) or nontargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 peptide (control, n = 10). Mice were injected intravenously with either compound on days 3 and 10 after tumor implantation, and tumor volumes were measured every day until the end of the experiment (day 11). In this first preclinical trial, BMTP-11 induced a clear delay in tumor growth compared with the untargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 (control), which was significant after treatment (P < 0.05) (Figure 4C). A similar treatment regimen was applied to the lung colonization model, followed by evaluation of total lung weight plus pulmonary tumor count. In this second preclinical trial, administration of BMTP-11 resulted in a reduction in total weight of the lungs (P < 0.0001) (Figure 4D) and in the number of lung tumors (P = 0.002) (Figure 4E), yet another indication of therapeutic efficacy. No tissue damage was observed by histologic evaluation in the nonmalignant portion of the lungs.

Figure 4.

In vivo pharmacologic activity of BMTP-11 in subcutaneous and lung colonization mouse models of human lung cancer. IL-11R expression was evaluated in the mouse models by immunohistochemistry. A: Representative subcutaneous tumor (left) and corresponding control staining with secondary antibody only (right). B: Lung tumor (left) with evidence of membrane IL-11R staining (left, arrows). C: Effect of BMTP-11 treatment on the growth of subcutaneous primary tumors. Mice received an intravenous administration of 10 mg/kg BMTP-11 or nontargeted D[KLAKLAK]2 peptide (control) on days 3 and 10 (arrows). D: Lung weights of mice injected into the tail vein with lung cancer cells and treated with BMTP-11 or control peptide. E: Number of tumors in bilateral lungs dissected from mice treated with either BMTP-11 or control peptide. Data are expressed as mean tumor volumes ± SEM (C). n = 10 treated mice (C–E); n = 10 control mice (C); n = 9 treated mice (D and E); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Scale bars: 100 μm (A and B).

These results indicate that in both preclinical models, BMTP-11 could effectively target the tumor site and inhibit tumor growth.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluate IL-11R as an unrecognized molecular target in lung cancer and also the efficacy of targeting IL-11R with BMTP-11 in preclinical models of tumor cell lines and tumor-bearing mice. First, we show that IL-11R is highly and consistently expressed in a large panel of surgical lung cancer specimens. Moreover, BMTP-11 is therapeutically active in killing multiple lung cancer cell lines in vitro. Finally, we show that BMTP-11 causes delay in tumor growth in subcutaneous animal models of lung cancer and a reduction in the establishment of tumors in a lung colonization model.

High expression of the IL-11R-native ligand, IL-11, has been associated with lung cancer31, 32 and with the capacity of tumor cells to metastasize to the lungs,33 suggesting a functional role in this specific pathologic setting and encouraging the exploitation of IL-11R as a potential therapeutic target. We show that IL-11R is overexpressed in human specimens of primary lung cancer, in which high cytoplasmic levels are associated with receptor presence on the cell membrane. This accumulation of IL-11R at the cell membrane was actually observed also in other cancers, including gastric and colorectal carcinoma.17, 18 In this light, and because it might be difficult to assess membrane localization in the presence of overwhelming cytoplasmic staining, we propose to adopt the overall expression of IL-11R as a biomarker of potential response to BMTP-11.

Confirming the robust specificity of IL-11R targeting in the tumor, here we report low, cytoplasm-confined levels of IL-11R in human nonmalignant bronchiolar epithelium. It is therefore conceivable that in normal tissue this target is not accessible by an extracellular ligand-directed drug, and, as a consequence, no toxicity is expected to affect the adjacent, nonmalignant lung tissue. This prerequisite is indeed confirmed by our present study and past findings. BMTP-11 has been described as an effective treatment for advanced osteosarcoma, including pulmonary metastasis.16 In this study, no in vivo accumulation of BMTP-11 and no damage to nonmalignant lung tissue were described. So far, the only known BMTP-11 toxicity is a dose-dependent, reversible nephrotoxicity, reported in a first-in-man (phase 0) clinical trial in cancer patients.22

Here, we also provide evidence of BMTP-11 antitumor activity against lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, the observed IC50 for the effects of the targeted drug on cell viability (33 to 120 μmol/L) are quite promising, also considering that only a portion (2% to 21%) of cultured lung cancer cells was positive for detectable surface membrane expression of IL-11R. These effects are attributable to BMTP-11–mediated induction of apoptosis, as we previously reported in prostate cancer cell lines,20 and in leukemia and lymphoma cell lines.21 In vivo, BMTP-11 was effective in repressing tumor growth both in a subcutaneous tumor xenograft and in a lung colonization model at relatively low molar doses (10 mg/kg). The higher efficacy of this drug in vivo is possibly related to an increased expression of IL-11R by cancer cells and/or to the observed presence in the vasculature in the tumor stroma. Although such a mechanism will need further validation, one might speculate that BMTP-11 would exert a synergistic effect by acting on both tumor components and on the tumor vasculature.

Conclusions

We propose BMTP-11 as a candidate drug that should be clinically evaluated in lung cancer patients. Meanwhile, a preference for higher scoring in ADC or smokers may help to select subjects with increased expression of IL-11R who would most benefit from IL-11R–targeted therapy, although further investigation is needed. Our results also introduce a new molecular marker of human NSCLC and provide a translational avenue for targeted treatment of patients. Given the ongoing success of translating approved molecularly targeted drugs to additional subsets of cancer patients and the preclinical and pathologic data reported here, we believe that BMTP-11 is a strong candidate drug for a similar translational path.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Marc Barry for technical assistance with the tissue microarray data.

All authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. M.C.-V., F.I.S., and A.J.Z. performed the experiments; G.Y. and J.J.L. performed statistical analysis; M. Sun examined the IHC; C.B. collected the clinical data; W.K.H. and I.I.W. performed pathologic analysis; M.C.-V., S.M., M. Sato, F.I.S., I.I.W., W.A., and R.P. designed the experiments and interpreted the data; M.C.-V., S.M., M. Sato, F.I.S., T.L.S., J.K.B., R.L.S., I.I.W., W.A., and R.P. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by the Department of Defense grant W81XWH-05-2-0027 (W.K.H., I.I.W., W.A., and R.P.); the Gillson-Longenbaugh Foundation and the Marcus Foundation (W.A. and R.P.); The University of Texas Lung Specialized Programs of Research Excellence grant P50CA70907 (I.I.W.); and MD Anderson's Institutional Tissue Bank Award 2P30CA016672 (I.I.W.) from the National Cancer Institute.

M.C.-V., S.M., and M. Sa. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: At the time of the study, R.P., W.A., and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center owned equity stock in Alvos Therapeutics (Arrowhead Research Corporation, Pasadena, CA). Arrowhead Research Corporation has licensed rights to patents and technologies described in this article. W.A. and R.P. report research sponsorship, including grants, and other support from Arrowhead Research Corporation and were shareholders in the company at the time of the study. The University manages and monitors the terms of these arrangements in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.04.013.

Contributor Information

Wadih Arap, Email: warap@salud.unm.edu.

Renata Pasqualini, Email: rpasqual@salud.unm.edu.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Liao Z., Lin S.H., Cox J.D. Status of particle therapy for lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:745–756. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.590148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanoue L.T., Tanner N.T., Gould M.K., Silvestri G.A. Lung cancer screening. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:19–33. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201410-1777CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society . American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2015. Cancer Facts & Figures. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scarpaci A., Mitra P., Jarrar D., Masters G.A. Multimodality approach to management of stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2013;22:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandler A., Gray R., Perry M.C., Brahmer J., Schiller J.H., Dowlati A., Lilenbaum R., Johnson D.H. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirker R., Pereira J.R., Szczesna A., von Pawel J., Krzakowski M., Ramlau R., Vynnychenko I., Park K., Yu C.T., Ganul V., Roh J.K., Bajetta E., O'Byrne K., de Marinis F., Eberhardt W., Goddemeier T., Emig M., Gatzemeier U., FLEX Study Team Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): an open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1525–1531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pirker R., Pereira J.R., von Pawel J., Krzakowski M., Ramlau R., Park K., de Marinis F., Eberhardt W.E., Paz-Ares L., Storkel S., Schumacher K.M., von Heydebreck A., Celik I., O'Byrne K.J. EGFR expression as a predictor of survival for first-line chemotherapy plus cetuximab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of data from the phase 3 FLEX study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:33–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi A., Maione P., Sacco P.C., Sgambato A., Casaluce F., Ferrara M.L., Palazzolo G., Ciardiello F., Gridelli C. ALK inhibitors and advanced non-small cell lung cancer (review) Int J Oncol. 2014;45:499–508. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon B.J., Mok T., Kim D.W., Wu Y.L., Nakagawa K., Mekhail T., Felip E., Cappuzzo F., Paolini J., Usari T., Iyer S., Reisman A., Wilner K.D., Tursi J., Blackhall F., PROFILE 1014 Investigators First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167–2177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arap W., Kolonin M.G., Trepel M., Lahdenranta J., Cardo-Vila M., Giordano R.J., Mintz P.J., Ardelt P.U., Yao V.J., Vidal C.I., Chen L., Flamm A., Valtanen H., Weavind L.M., Hicks M.E., Pollock R.E., Botz G.H., Bucana C.D., Koivunen E., Cahill D., Troncoso P., Baggerly K.A., Pentz R.D., Do K.A., Logothetis C.J., Pasqualini R. Steps toward mapping the human vasculature by phage display. Nat Med. 2002;8:121–127. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pentz R.D., Cohen C.B., Wicclair M., DeVita M.A., Flamm A.L., Youngner S.J., Hamric A.B., McCabe M.S., Glover J.J., Kittiko W.J., Kinlaw K., Keller J., Asch A., Kavanagh J.J., Arap W. Ethics guidelines for research with the recently dead. Nat Med. 2005;11:1145–1149. doi: 10.1038/nm1105-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staquicini F.I., Cardó-Vila M., Kolonin M.G., Trepel M., Edwards J.K., Nunes D.N., Sergeeva A., Efstathiou E., Sun J., Almeida N.F., Tu S.M., Botz G.H., Wallace M.J., O'Connell D.J., Krajewski S., Gershenwald J.E., Molldrem J.J., Flamm A.L., Koivunen E., Pentz R.D., Dias-Neto E., Setubal J.C., Cahill D.J., Troncoso P., Do K.A., Logothetis C.J., Sidman R.L., Pasqualini R., Arap W. Vascular ligand-receptor mapping by direct combinatorial selection in cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18637–18642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114503108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardó-Vila M., Zurita A.J., Giordano R.J., Sun J., Rangel R., Guzman-Rojas L., Anobom C.D., Valente A.P., Almeida F.C., Lahdenranta J., Kolonin M.G., Arap W., Pasqualini R. A ligand peptide motif selected from a cancer patient is a receptor-interacting site within human interleukin-11. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell C.L., Jiang Z., Savarese D.M., Savarese T.M. Increased expression of the interleukin-11 receptor and evidence of STAT3 activation in prostate carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63940-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis V.O., Ozawa M.G., Deavers M.T., Wang G., Shintani T., Arap W., Pasqualini R. The interleukin-11 receptor alpha as a candidate ligand-directed target in osteosarcoma: consistent data from cell lines, orthotopic models, and human tumor samples. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1995–1999. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakayama T., Yoshizaki A., Izumida S., Suehiro T., Miura S., Uemura T., Yakata Y., Shichijo K., Yamashita S., Sekin I. Expression of interleukin-11 (IL-11) and IL-11 receptor alpha in human gastric carcinoma and IL-11 upregulates the invasive activity of human gastric carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:825–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshizaki A., Nakayama T., Yamazumi K., Yakata Y., Taba M., Sekine I. Expression of interleukin (IL)-11 and IL-11 receptor in human colorectal adenocarcinoma: IL-11 up-regulation of the invasive and proliferative activity of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:869–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanavadi S., Martin T.A., Watkins G., Mansel R.E., Jiang W.G. Expression of interleukin 11 and its receptor and their prognostic value in human breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:802–808. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karjalainen K., Jaalouk D.E., Bueso-Ramos C., Bover L., Sun Y., Kuniyasu A., Driessen W.H., Cardó-Vila M., Rietz C., Zurita A.J., O'Brien S., Kantarjian H.M., Cortes J.E., Calin G.A., Koivunen E., Arap W., Pasqualini R. Targeting IL11 receptor in leukemia and lymphoma: a functional ligand-directed study and hematopathology analysis of patient-derived specimens. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3041–3051. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zurita A.J., Troncoso P., Cardó-Vila M., Logothetis C.J., Pasqualini R., Arap W. Combinatorial screenings in patients: the interleukin-11 receptor alpha as a candidate target in the progression of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:435–439. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasqualini R., Millikan R.E., Christianson D.R., Cardó-Vila M., Driessen W.H., Giordano R.J., Hajitou A., Hoang A.G., Wen S., Barnhart K.F., Baze W.B., Marcott V.D., Hawke D.H., Do K.A., Navone N.M., Efstathiou E., Troncoso P., Lobb R.R., Logothetis C.J., Arap W. Targeting the interleukin-11 receptor alpha in metastatic prostate cancer: a first-in-man study. Cancer. 2015;121:2411–2421. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchiò S., Lahdenranta J., Schlingemann R.O., Valdembri D., Wesseling P., Arap M.A., Hajitou A., Ozawa M.G., Trepel M., Giordano R.J., Nanus D.M., Dijkman H.B., Oosterwijk E., Sidman R.L., Cooper M.D., Bussolino F., Pasqualini R., Arap W. Aminopeptidase A is a functional target in angiogenic blood vessels. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arap M.A., Lahdenranta J., Mintz P.J., Hajitou A., Sarkis A.S., Arap W., Pasqualini R. Cell surface expression of the stress response chaperone GRP78 enables tumor targeting by circulating ligands. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giordano R.J., Lahdenranta J., Zhen L., Chukwueke U., Petrache I., Langley R.R., Fidler I.J., Pasqualini R., Tuder R.M., Arap W. Targeted induction of lung endothelial cell apoptosis causes emphysema-like changes in the mouse. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29447–29460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804595200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Cesare M., Pratesi G., Veneroni S., Bergottini R., Zunino F. Efficacy of the novel camptothecin gimatecan against orthotopic and metastatic human tumor xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7357–7364. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo T.H., Kubota T., Watanabe M., Furukawa T., Kase S., Tanino H., Nishibori H., Saikawa Y., Teramoto T., Ihsibiki K., Kitajima M., Hoffman R.M. Orthotopic reconstitution of human small-cell lung carcinoma after intravenous transplantation in SCID mice. Anticancer Res. 1992;12:1407–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raso M.G., Behrens C., Herynk M.H., Liu S., Prudkin L., Ozburn N.C., Woods D.M., Tang X., Mehran R.J., Moran C., Lee J.J., Wistuba I.I. Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors identifies a subset of NSCLCs and correlates with EGFR mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5359–5368. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behrens C., Feng L., Kadara H., Kim H.J., Lee J.J., Mehran R., Hong W.K., Lotan R., Wistuba I.I. Expression of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 in non-small cell lung carcinoma and preneoplastic lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;16:34–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun M., Behrens C., Feng L., Ozburn N., Tang X., Yin G., Komaki R., Varella-Garcia M., Hong W.K., Aldape K.D., Wistuba I.I. HER family receptor abnormalities in lung cancer brain metastases and corresponding primary tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4829–4837. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luis-Ravelo D., Anton I., Zandueta C., Valencia K., Ormazabal C., Martinez-Canarias S., Guruceaga E., Perurena N., Vicent S., De Las Rivas J., Lecanda F. A gene signature of bone metastatic colonization sensitizes for tumor-induced osteolysis and predicts survival in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:5090–5099. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wysoczynski M., Ratajczak M.Z. Lung cancer secreted microvesicles: underappreciated modulators of microenvironment in expanding tumors. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1595–1603. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calon A., Espinet E., Palomo-Ponce S., Tauriello D.V., Iglesias M., Cespedes M.V., Sevillano M., Nadal C., Jung P., Zhang X.H., Byrom D., Riera A., Rossell D., Mangues R., Massague J., Sancho E., Batlle E. Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-beta-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:571–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.