Highlight

A functional analysis is conducted on two structurally related soybean WRKY proteins, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, and they are found to play a critical role in plant growth and flowering.

Key words: AtWRKY54, AtWRKY70, flowering, plant growth, soybean, virus-induced gene silencing, WRKY transcription factors.

Abstract

WRKY transcription factors constitute a large protein superfamily with a predominant role in plant stress responses. In this study we report that two structurally related soybean WRKY proteins, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, play a critical role in plant growth and flowering. GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are both Group III WRKY proteins with a C2HC zinc finger domain and are close homologs of AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54, two well-characterized Arabidopsis WRKY proteins with an important role in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are both localized to the nucleus, recognize the TTGACC W-box sequence with a high specificity, and function as transcriptional activators in both yeast and plant cells. Expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 was detected at low levels in roots, stem, leaves, flowers, and pods. Expression of the two genes in leaves increased substantially during the first 4 weeks after germination but steadily declined thereafter with increased age. To determine their biological functions, transgenic Arabidopsis plants were generated overexpressing GmWRKY58 or GmWRKY76. Unlike AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54, overexpression of GmWRKY58 or GmWRKY76 had no effect on disease resistance and only small effects on abiotic stress tolerance of the transgenic plants. Significantly, transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmWRKY58 or GmWRKY76 flowered substantially earlier than control plants and this early flowering phenotype was associated with increased expression of several flowering-promoting genes, some of which are enriched in W-box sequences in their promoters recognized by GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. In addition, virus-induced silencing of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in soybean resulted in stunted plants with reduced leaf expansion and terminated stem growth. These results provide strong evidence for functional divergence among close structural homologs of WRKY proteins from different plant species.

Introduction

WRKY proteins, first discovered just over 20 years ago, are a class of sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factors (Rushton et al., 2010). Although genes encoding WRKY proteins are found in non-photosynthetic eukaryotes, it is in higher plants where genes encoding WRKY proteins have greatly proliferated into large families, with more than 70 members in Arabidopsis thaliana and more than 100 members in rice (Wu et al., 2005; Zhang and Wang, 2005; Rushton et al., 2010). WRKY proteins contain the highly conserved WRKY domain, with the almost invariant WRKYGQK sequence at the N-terminus followed by a C2H2 or C2HC zinc-finger motif (Rushton et al., 2010). WRKY proteins were initially classified into three groups based on the number and sequence of the conserved WRKY zinc-finger motifs (Eulgem et al., 2000). Group I WRKY proteins contain two C2H2 zinc-finger motifs, whereas Group II WRKY proteins contain one C2H2 zinc-finger motif, and Group III WRKY proteins contain one C2HC zinc-finger motif. Further analyses have shown that Group II WRKY proteins can be further divided into five subgroups (IIa, IIb, IIc, IId, and IIe) (Zhang and Wang, 2005; Rushton et al., 2010). There is only a single Group I WRKY gene in the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the non-photosynthetic slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum, and the unicellular protist Giardia lamblia, suggesting that Group I WRKY proteins with two WRKY domains are the ancestors to the other groups of WRKY proteins (Zhang and Wang, 2005). The ancestral Group I WRKY gene was likely to have been generated from domain duplication of a proto-WRKY gene with a single WRKY domain. Subsequent loss of the N-terminal WRKY domain of Group I WRKY genes led to Goup II and Group III WRKY genes with a single WRKY domain, with Group III genes being evolutionarily the last. However, comparative studies of more recently available genome sequences from the filamentous terrestrial alga Klebsormidium flaccidum and the spike moss Selaginella moellendorffii have raised questions about whether all WRKY genes evolved from an ancestral Group I WRKY gene (Rinerson et al., 2015). Furthermore, both the spike moss S. moellendorffii and the moss Physcomitrella patens contain Group III or Group III-like WRKY genes but lack specific subgroups of Group II WRKY genes, suggesting that Group III WRKY genes are probably not the youngest group of WRKY genes (Rinerson et al., 2015).

A large number of studies have established that plant WRKY transcription factors play critical roles in the two interconnected branches of the plant innate immune system: pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP-triggered immunity or PTI) and pathogen virulent effectors (effector-triggered immunity or ETI) (Jones and Dangl, 2006). It has been widely reported that many WRKY genes from a wide range of plant species are responsive to pathogens or pathogen elicitors. In Arabidopsis, more than 70% of the WRKY gene family members are responsive to pathogen infection and salicylic acid (SA) treatment (Dong et al., 2003). Studies using knockout or knockdown mutants or overexpression lines of WRKY genes have shown that WRKY transcription factors can positively or negatively regulate plant PTI and ETI (Chen and Chen, 2000, 2002; Li et al., 2004, 2006; Eulgem, 2006; Kim et al., 2006, 2008; Xu et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2006, 2007; Eulgem and Somssich, 2007; Lai et al., 2008, 2011; Pandey and Somssich, 2009; Mao et al., 2011). Well-characterized signaling pathways leading to the induction or activation of specific WRKY proteins and their subsequent activation of downstream target genes in plant defense responses have also been reported. WRKY proteins also regulate plant responses to a broad spectrum of abiotic stresses including heat, salt, osmotic, and drought stress (Jiang et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2013, 2014, 2015; Hu et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2013; Sun and Yu, 2015). Other studies have shown that WRKY proteins are involved in hormone signaling (Shang et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2015), secondary metabolism (Wang et al., 2010; Suttipanta et al., 2011) and other important processes associated with plant stress responses. There are also a number of reports on the role of WRKY proteins in the regulation of plant growth and developmental processes, including trichome (Johnson et al., 2002) and seed development (Luo et al., 2005), germination (Jiang and Yu, 2009), and leaf senescence (Robatzek and Somssich, 2002; Miao et al., 2004). Thus, even though WRKY proteins have important roles in diverse biological processes in plants, their predominant functions appear to be the regulation of plant responses to a broad spectrum of biotic and abiotic stresses.

Among the large number of reported studies on the roles of WRKY transcription factors, the vast majority of them have been carried out in the model plants Arabidopsis and, to a less extent, rice, while only a relatively few studies have reported on WRKY proteins from other plants including important crop species. Comparative analyses of sequenced plant genomes have revealed a great variation in the number of WRKY genes in different plant species, due to differences in the frequencies in both large-scale genome duplications and small-scale gene duplications (Rinerson et al., 2015). Furthermore, although WRKY homologs from different species are highly similar in the conserved WRKY domain regions, they can display substantial sequence divergence in other regions, which could lead to differences in their functions. Therefore, efforts in analyzing WRKY genes from non-model plants could lead to discoveries of new or even novel functions of this important superfamily of transcription factors. In the present study, we report a functional analysis of two structurally related soybean WRKY proteins, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, in plant growth and development. GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are close homologs of Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54, two well-characterized Group III WRKY proteins with a critical role in plant defense and stress responses (Li et al., 2004, 2006, 2013; Knoth et al., 2007; Besseau et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2012; Shim and Choi, 2013; Shim et al., 2013). However, unlike AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54, overexpression of GmWRKY58 or GmWRKY76 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants had no major effect on disease resistance or abiotic stress tolerance but could substantially promote flowering and increased expression of flowering-related genes of transgenic plants. Most importantly, virus-induced silencing of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in soybean caused severe stunted growth with reduced size of leaves and plant stature. The critical role of the two soybean WRKY genes in plant growth and development is consistent with their patterns of elevated expression in relatively young leaves of soybean plants and their binding to the promoters of some flowering-related genes from Arabidopsis. These results strongly suggest that close structural homologs of WRKY proteins from different plant species can evolve into functionally divergent WRKY proteins that regulate distinct biological processes in plants.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Soybean (Glycine max cv ‘Williams 82’) and tobacco plants were grown in a greenhouse or a growth room at 25 °C with a 12/12h hour light/dark photoperiod. Arabidopsis plants were grown at 24 °C light/22 °C dark with a 12/12h photoperiod.

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Group III proteins

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGAv5. The full sequences of Group III WRKYs in Arabidopsis, rice, and soybean (see Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online) were used to construct multiple sequence alignments using Clustal W. A phylogenetic tree was produced following neighbor-joining method using the aligned sequences.

Production of recombinant proteins and electrophoretic mobility shifting assay (EMSA)

For generation of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 recombinant protein, their full-length cDNAs were PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (5′- AGCGGATCCATGAGTATTCTCTTCCC AAGAAGT-3′ and 5′- AGCAAGCTTCTAAAGCAATTGGCTTT CATCAAAG -3′), cloned into pET32a (Novagen, San Diego, CA, USA). The cloned GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 genes in the recombinant pET32a vector were confirmed by sequencing, and transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). Induction of protein expression and purification of recombinant His-tagged proteins were performed according to the protocol provided by Novagen. The recombinant proteins were purified according to the Novagen manual. Oligo nucleotides were labeled using the Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A DNA binding assay was performed based on the Light Shift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Assays of transcription-activating activity in yeast and plant cells

The full-length coding sequences of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 were PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (5′-AGCGAATTCA TGAGTATTCTCTTCCCAAGAAGT-3′ and 5′-AGCGTCGA CGCTAAAGCAATTGGCTTTCATCAAAG-3′) and cloned into pBD-Gal4Cam to generate translational in-frame fusion with the DNA-binding domain of GAL4 transcription factor. The pBD-WRKY fusion constructs were transformed into yeast strain YRG-2. Transcription-activating activity of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in yeast cells were determined by the LacZ reporter gene expression using assays of β-galactosidase activity. The empty pBD-Gal4Cam vector was used as a control.

The transcriptional regulatory activities of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in plant cells were determined using a previously described GUS reporter gene system (Kim et al., 2006). The GUS reporter gene is driven by a synthetic promoter consisting of the –100-nucleotide minimal CaMV 35S promoter and eight copies of the LexA operator sequence (Kim et al., 2006). For generating effector genes, the DNA fragment for the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of LexA was fused with GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 coding sequences and the translational fusion genes were cloned into the pTA7002 vector behind the glucocorticoid-inducible promoter (Aoyama and Chua, 1997). As control, the unfused LexA DBD, GmWRKY58, and GmWRKY76 genes were also cloned into pTA7002. Arabidopsis plant protoplasts were prepared from 4-week-old Arabidopsis leaves using the tape-Arabidopsis sandwich method (Wu et al., 2009) and transfected with the effector constructs a combination with the GUS reporter construct. Transfected protoplasts with each effector/report combination were divided into two equal aliquots and dexamethasone (DEX) was added into one of the aliquots to a final concentration of 5 µM to induce expression of the effector gene. After 20h, protoplasts were harvested and the GUS activities from transfected protoplasts with or without DEX treatment were determined and compared. GUS activity was measured through a 4-methylumbellifery-β-D-glucuronide substrate assay.

Subcellular localization

DNA fragments for full-length or N-terminal domains of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 proteins were PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (5′-AGCGAGCTCATGAGTATT CTCTTCCCAAGAAGT -3′ and 5’-AGCGGATCCAAGCAATT GGCTTTCATCAAAG -3′) and fused to a GFP plasmid. Correct sequences and fusion of the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Agrobacterium cells containing the GFP fusion constructs were introduced into leaves of transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana that expresses a histone 2B fused with a red fluorescent protein (RFP-H2B) as a marker for the nucleus (Yang et al., 2011). Infected leaves were analyzed at approximately 24h after infiltration. Images were observed by confocal laser microscopy.

Analysis of gene expression using qRT-PCR

Soybean tissue samples were lyophilized and stored at –80 °C until use. Total RNA was isolated from soybean tissues using the Trizol reagent according to the supplier’s instruction. Extracted RNA was treated with DNase to remove contaminating DNA and reverse transcribed using the ReverTran Ace® qPCR RT kit (Toyobo) for reverse transcriptase-PCR. qRT-PCR was performed with an StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (ABI). PCRs were performed using the SYBR® Green qPCR Master Mixes (Takara) and gene-specific primers (see Supplementary Table S2). The PCR conditions consisted of denaturation at 95 °C for 1min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15s, annealing and extension at 58 °C for 30s. Melt curve analysis was performed on the end products of PCR, to determine the specificity of reactions. Relative quantification of gene expression was calculated according to the ΔΔCt method. The soybean Actin gene (Gm18g52780) was used as internal control.

Generation of transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 Arabidopsis plants

For generating transgenic GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-expressing Arabidopsis plants, the full-length coding sequences were amplified using gene specific primers (5′-AGCGTCGACATG AGTATTCTCTTCCCAAGAAGTTC-3′ and 5′-AGCGGATCCCT AAAGCAATTGGCTTTCATCAA-3′). The amplified fragments were digested using appropriate restriction enzymes and inserted into the plant transformation vector pFGC5941 containing the CaMV 35S promoter. The fused plasmids were transformed into Col-0 wild-type plants using the Agrobacterium-mediated floral-dip procedure (Clough and Bent, 1998). Transformants were identified for resistance to Basta herbicide. Transgenic plants overexpressing the transformed GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 transgene were identified using RT-qPCR.

Phenotypic analysis of transgenic Arabidopsis plants

Pathogen inoculations were performed by infiltration of leaves of 6 to 10 plants for each treatment with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (PstDC3000) (OD600=0.0001 in 10mM MgCl2). Inoculated leaves were harvested 3 d post inoculation and homogenized in 10mM MgCl2. Diluted leaf extracts were plated on King’s B medium supplemented with rifampicin (100 µg ml–1) and kanamycin (25 µg ml–1) and incubated at 25 °C for 2 d before counting the colony-forming units.

For determining plant tolerance to osmotic stress, 4-week-old plants were watered with 15% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000 solution for 3 d. Control plants received water. For electrolyte leakage determination, plant material (0.5g) was washed with deionized water and placed in tubes with 20ml of deionized water. The electrical conductivity of this solution (L1) was measured after 1h of shaking at room temperature. Then, the samples were boiled for 20min and measured a second time for conductivity (L2). The electrolyte leakage was calculated as follows: EL (%) = (L1/L2)×100%. For determination of germination, seeds of WT and transgenic plants were surface-sterilized and sown on half-strength MS medium containing varying concentrations of NaCl, mannitol or abscisic acid (ABA). The plates were incubated for 48h at 4 °C and then transferred to an incubator at 25 °C (12h day/night photoperiod). The germination rates were scored for 4 d after transfer to 25 °C.

Chromatin immunoprepitation (ChIP)

For ChIP assays, we first generated the 35S::GmWRKY58-4myc and 35S::GmWRKY76-4myc constructs and Arabidopsis protoplasts were transfected with the construct DNA. After 24h, protoplasts were harvested and ChIP assays were conducted using anti-myc antibody or mouse IgG (negative control), as described previously (Mao et al., 2011). qPCRs were performed on the immunoprecipitated DNA and input DNA using primer pairs specific for the promoter regions of flowering time genes (see Supplementary Table S3). The ChIP results are shown as percentage of input DNA.

BPMV-mediated gene silencing

DNA fragments of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 genes were PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers and cloned into BPMV RNA2 silencing vector (Zhang et al., 2010, 2013). Inoculation of soybean seedlings at the V1 stage with DNA-based BPMV constructs via biolistic particle bombardments was performed as described previously (Zhang et al., 2010, 2013). At 3 weeks post-virus inoculation, the third trifoliate leaves were harvested to isolate RNA for detection of BPMV by RT-PCR and verification of gene silencing by qRT-PCR.

Results

Protein structures of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76

Our study of soybean GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 originated from our interest in identifying those members of the soybean WRKY superfamily that are capable of enhancing pathogen resistance and stress tolerance when overexpressed in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. From the sequenced soybean genome, we initially identified more than 170 WRKY genes and analyzed their expression in response to pathogens, abiotic stresses, and defense- and stress-related phytohormones such as salicylic acid (SA) and ABA. From the expression analysis, we identified more than 100 defense/stress-responsive soybean WRKY genes. To analyze more directly their ability to affect plant defense and stress responses, we generated overexpression constructs under the strong CaMV 35S promoter for the stress/defense-responsive soybean WRKY genes and transformed some of them into the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the vast majority of the stress-responsive soybean WRKY genes displayed no significant alteration in plant morphology, growth, and development. As will be described later in detail, however, transgenic plants overexpressing soybean GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 were not altered in plant disease resistance or stress tolerance but were substantially altered in flowering time when compared to control plants, suggesting their specific role in plant growth and development.

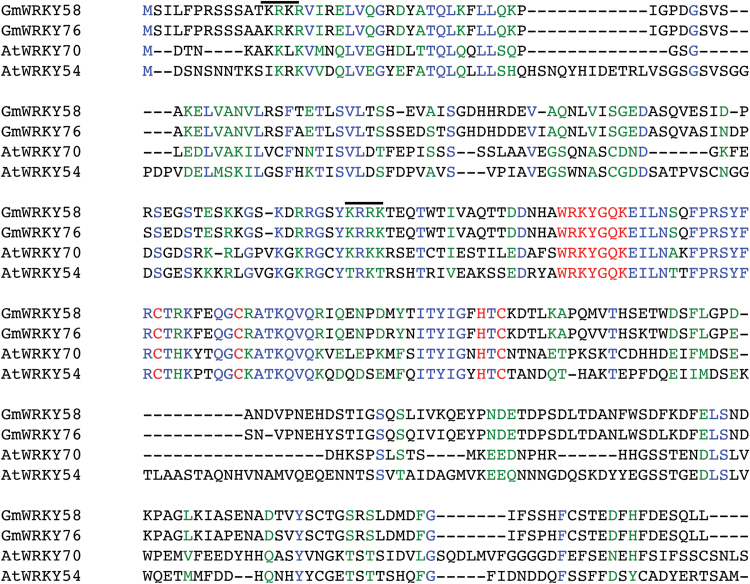

GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are close homologs that share 91% identical amino acid residues (Fig. 1). Both GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are Group III WRKY proteins, each containing a single WRKY domain with a C2HC zinc finger structure (Fig. 1). A BLAST search against the 72 identified Arabidopsis WRKY proteins showed that GmWRKY58 and GMWRKY76 are most closely related to AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 (Fig. 1), two of the most analyzed Arabidopsis WRKY proteins with critical roles in plant responses to both biotic and abiotic stresses (Li et al., 2004, 2006, 2013; Knoth et al., 2007; Besseau et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2012; Shim and Choi, 2013; Shim et al., 2013). As expected, the two soybean WRKY paralogs shared the highest homology with the two Arabidopsis WRKY proteins in the DNA-binding WRKY domain, but substantial sequence similarities were also found in the N-terminal regions of the proteins (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the sequences of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are highly divergent from those of AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 in the C-terminal region. No other known structural motifs were identified from GmWRKY58 or GmWRKY76, apart from the highly conserved WRKY domain.

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 with the AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 homologs from Arabidopsis. Amino acids identical in four proteins are blue, and residues similar in four proteins are green. The WRKY DNA binding motifs with the highly conserved WRKYGQK sequences and the residues forming the C2HC zinc-fingers are red. Putative nuclear localization signals are indicated by bars.

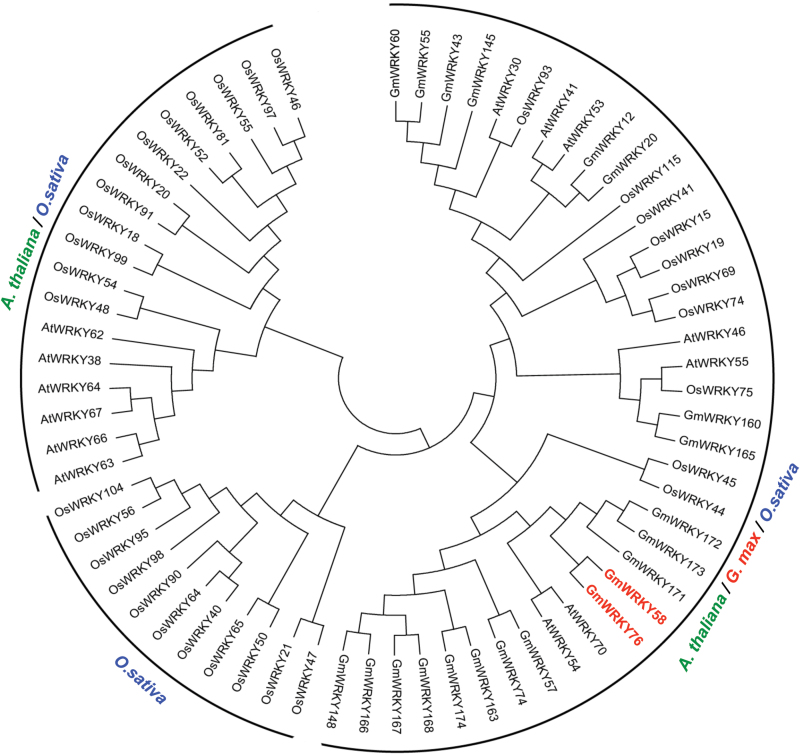

To further analyze the structural relationship of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 with other Group III WRKY proteins, we generated a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of Group III WRKY proteins from Arabidopsis, soybean, and rice. The tree contains subclades with proteins from all three plant species or subclades with proteins exclusively from one or two plant species (Fig. 2). Most notably, a subclade consists of Group III WRKY proteins exclusively from rice, most likely reflecting the monocot nature of rice and thus evolutionarily more distantly related to the two dicot plants (Fig. 2). In addition, the phylogenetic analysis confirmed that soybean GmWRKY58 and GMWRKY76 are structurally closely related to Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 (Fig. 2). Three other soybean Group III proteins, GmWRKY171, GmWRKY172, and GmWRKY173, are also structurally closely related to GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 (Fig. 2). These three Group III WRKY proteins are encoded by three clustered genes on Chromosome 14, most likely resulting from local gene duplication.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Group III WRKY proteins from Arabidopsis, soybean, and rice. The full sequences of group III WRKYs in Arabidopsis, rice, and soybean were used to construct multiple sequence alignments using Clustal W. The phylogenetic tree was produced with the aligned sequences following the neighbor-joining method using MEGAv5. Three subclades with proteins from one, two, and all three plant species are indicated. GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are highlighted on the tree in red.

DNA binding and transcription-activating activities and subcellular localization

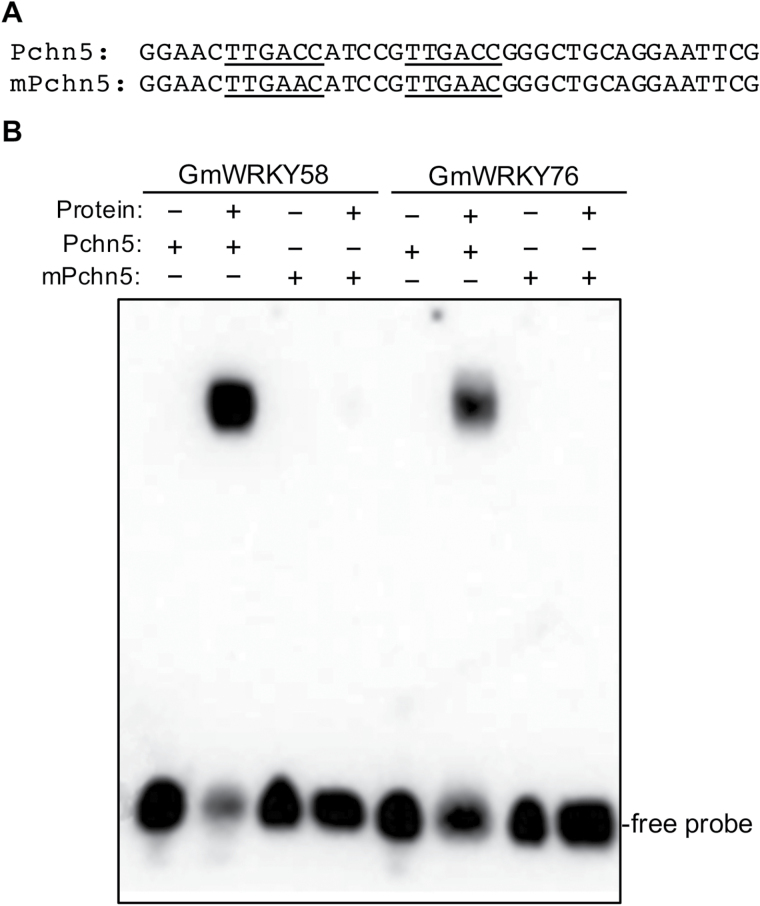

WRKY transcription factors recognize the TTGACC/T W-box sequences, which occur at high frequencies in the promoters of defense/stress-induced genes (Dong et al., 2003). To examine the DNA-binding activity of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, we expressed the genes in E. coli, purified the recombinant proteins, and analyzed their binding to an oligonucleotide that contains two direct TTGACC repeats (Pchn5; Fig. 3A) using an electrophoretic mobility shifting assay (EMSA). A protein/DNA complex with a reduced mobility was detected when purified recombinant GmWRKY58 or GmWRKY76 protein was incubated with the Pchn5 probe (Fig. 3B). Binding of GmWRKY58 or GmWRKY76 was not detected with a mutant probe (mPchn5) in which both TTGACC sequences were changed to TTGAAC (Fig. 3). Thus, binding of the two soybean Group III WRKY proteins to the TTGACC W-box sequence is highly specific.

Fig. 3.

W-box-binding activities of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. (A) Nucleotide sequences of probes used for DNA binding assays. Pchn5 contains two TTGACC W-box sequences, which are mutated into TTGAAC in mPchn5. (B) Recombinant GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 were purified from E. coli cells and used for DNA binding assays with Pchn5 and mPchn5 as probes. The binding reactions (20 µl) contained 2ng labeled oligo DNA, 5 µg polydeoxyinosinic-deoxycytidylic acid, and 1 µg recombinant protein. The binding assays were repeated twice with independently prepared recombinant proteins with similar results.

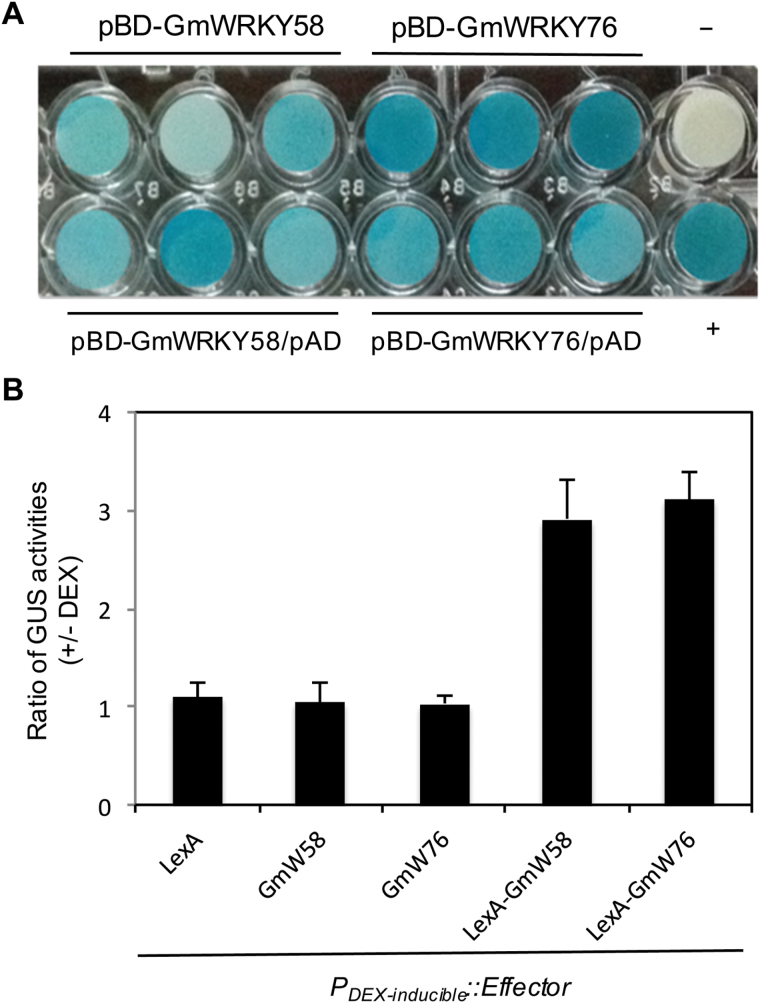

We also analyzed the transcriptional activating activity of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in both yeast and plant cells. The protein-coding regions of the GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 cDNAs were inserted downstream of the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) in a yeast transformation plasmid. These fusion constructs were then introduced into the yeast strain YRG-2, in which two reporter genes (HIS3 and LacZ) are under the control of the GAL4 binding sites. As shown in Fig. 4A, yeast cells transformed with the fusion construct contained high levels of β-Gal activity. These yeast cells were also able to grow on media without histidine (data not shown). These results indicate that the fusion proteins of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are capable of activating both HIS3 and LacZ reporter genes and, therefore, are transcriptional activators in yeast cells. The transcriptional regulatory activities of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in plant cells were determined using a previously described GUS reporter gene system (Kim et al., 2006). The GUS reporter gene is driven by a synthetic promoter consisting of the –100-nucleotide minimal CaMV 35S promoter and eight copies of the LexA operator sequence. To generate effector genes, we fused the LexA DBD sequence with those of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 coding sequences in pTA7002 vector behind its steroid-inducible promoter (Aoyama and Chua, 1997). Unfused LexADBD, GmWRKY58, and GmWRKY76 genes were also cloned into pTA7002 as negative controls. Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts were transfected with different effector/reporter combinations and changes in GUS reporter activity as a result of DEX-induced expression of introduced effector genes were determined. As shown in Fig. 4B, induced expression of unfused LexA DBD, GmWRKY58, and GmWRKY76 genes did not affect the co-transfected GUS reporter gene expression. By contrast, induced expression of fused LexA DBD-GmWRKY58 and LexA DBD-GmWRKY76 increased the GUS reporter activities by 2-fold. These results indicate that both GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 function as transcriptional activators in plant cells.

Fig. 4.

Transcription-activating activities of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. (A) The pBD-GmWRKY58 and pBD-GmWRKY76 fusion vectors were transformed alone (upper row) or in combination with a pAD empty vector (lower row) into yeast cells. Activation of the LacZ reporter gene in the yeast cells was determined by assays of the β-galactosidase activity with X-gal as substrate. Empty pBD (–) and pBD-WT/pAD-WT (+) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. (B) Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts were transfected with the construct of a GUS reporter gene under the control of a promoter containing copies of the LexA operator sequence in combination with an effector gene of LexA DBD (LexA), GmWRKY58, GmWRKY76, LexA DBD-GmWRKY58 (LexA-GmW58), or Lex ADBD-GmWRKY76 (LexA-GmW76) under the control of a DEX-inducible promoter in the pTA7002 vector. Transfected protoplasts were divided into two aliquots, to one of which was added 5 µM DEX to induce expression of the effector genes. GUS activities from transfected protoplasts with or without DEX treatment were determined 20h later and compared. GUS activity was measured through a 4-methylumbellifery-β-D-glucuronide substrate assay.

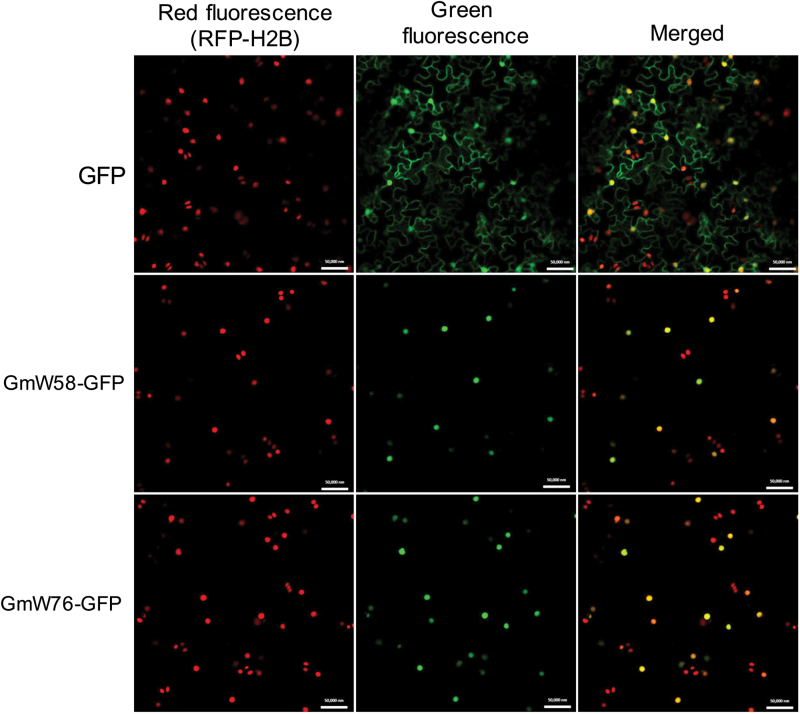

If GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 function as transcription factors, they are likely to be localized in the nucleus. At least two putative nuclear localization signals are present in GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 based on prediction by the PSORT II program (Fig. 1). To determine their subcellular location, we constructed GFP protein fusion of the two soybean WRKY proteins. The fusion constructs, driven by the CaMV 35S promoter, were agroinfiltrated for transient expression into transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) containing the nuclear marker histone 2B fused with red fluorescent protein (RFP-H2B) and confocal microscopy was performed on the leaf sections of agroinfiltrated plants. As shown in Fig. 5, the transiently expressed GmWRKY58-GFP and GmWRKY76-GFP fusion proteins were localized exclusively in the nucleus of tobacco cells. By contrast, GFP was found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm due to its small size.

Fig. 5.

Subcellular localization of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. The GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-GFP fusion genes were expressed transgenic N. benthamiana plants expressing a H2B-RFP nuclear marker. A majority of GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-GFP punctate fluorescence signals were also labeled by the H2B-RFP nuclear marker signals. Expression of unfused GFP generated both dispersed and punctate signals. Bars=10 µm.

Expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76

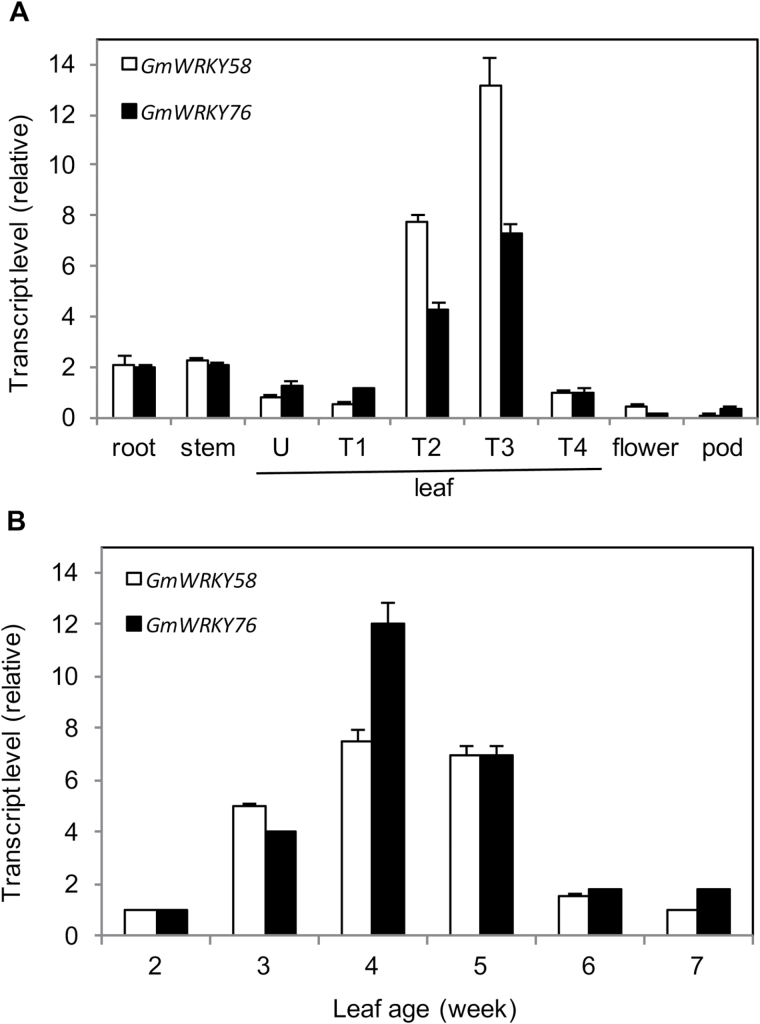

To further characterize GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, we examined their expression in soybean using qRT-PCR. First, we examined the transcript levels of the two WRKY genes in different soybean tissues. As shown in Fig. 6A, expression of both WRKY genes was detected in all tissues examined but the expression levels in roots, stem, and leaves were substantially higher than those in flowers and pods. We also compared unifoliate and trifoliate leaves for expression of the two WRKY genes and, interestingly, while transcripts for the two genes were detected in all these leaves, they were substantially higher in the second and third trifoliate leaves (Fig. 6A). This result suggests that expression of the genes in soybean leaves is developmentally regulated. To confirm this, we also examined the changes of transcripts levels of the two WRKY genes in the first trifoliate leaves of different ages. The expression of the genes was very low at young ages (2 weeks after germination), but steadily increased with age (Fig. 6B). By the 4th week after germination, the expression levels were about 8–12 times higher than those detected 2 weeks earlier (Fig. 6B). After peaking around the 4th week, the transcript levels of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 declined steadily with further increased age, returning close to the basal levels by the 6th week. Thus, expression of both GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in leaves started at very low levels, increased steadily in expanding leaves, remained highly expressed in relatively young expanded leaves, but then declined in old expanded leaves.

Fig. 6.

Tissue- and age-associated expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. (A) Expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in different plant tissues. Roots, stems, and leaves (U, unifoliate; T1, 1st trifoliate; T2, 2nd trifoliate; T3, 3rd trifoliate; T4, 4th trifoliate) were collected from seedlings when the third trifoliate leaves were fully expanded. Flowers were sampled from plants at reproductive 2 stage when the flowers were blooming, and pods were collected at 20-d post-flowering. (B) Age-regulated expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in soybean leaves. The first trifoliolate leaves were collected from 2-week-old seedlings to 7-week-old plants at 1-week intervals. GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 expression were analyzed by quantitative qRT-PCR using a soybean actin gene as an internal control. Values represent the means and standard errors of three replicates.

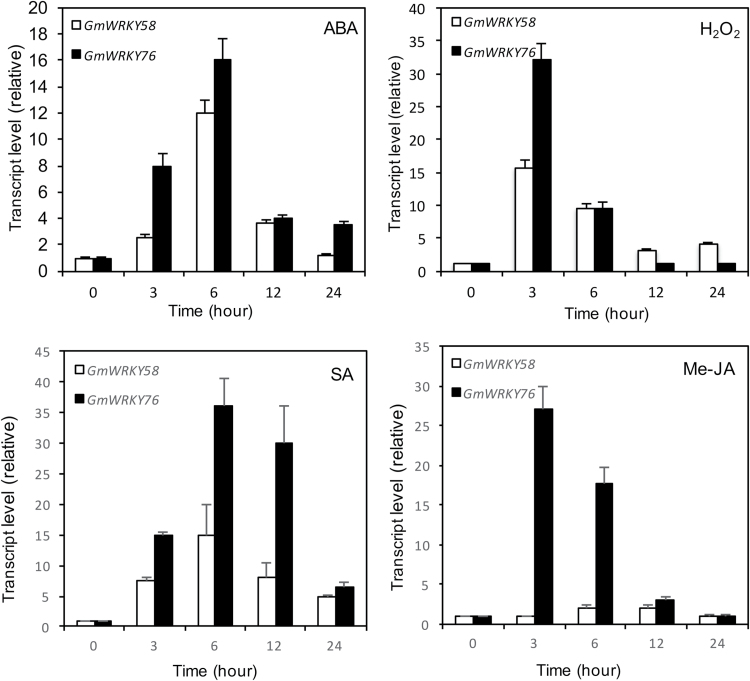

Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 are responsive to a range of biotic and abiotic stimuli (Li et al., 2013). To determine the possible involvement of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in plant stress responses, we analyzed their expression in response to ABA, H2O2, SA, and methyl jasmonic acid (Me-JA). As shown in Fig. 7, both soybean WRKY genes were induced by ABA. By the 6th hour after ABA treatment, the transcript levels of the two WRKY genes were induced by more than 10-fold. By the 12+th hour after ABA treatment, however, the transcript levels of the two WRKY genes had already declined substantially from the peak levels. Both GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 transcript levels were also elevated greatly upon H2O2 treatment and the kinetics of the induction, both in magnitude and speed, appeared to be stronger than with ABA treatment (Fig. 7). However, this induction of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 by H2O2 was also transient, as evident from their rapid decline from the peak levels at the 3rd hour after treatment. Expression of GmWRKY58 and, to a less extent, GmWRKY76 was also elevated in SA-treated plants (Fig. 7). Treatment with JA also greatly induced expression of GmWRKY76 but only marginally elevated the expression of GmWRKY58 (Fig. 7). Thus, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 were responsive to the stress hormones and to H2O2.

Fig. 7.

Expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in response to ABA, H2O2, salicylic acid (SA), and methyl JA (MeJA). The first trifoliolate leaves of 2.5-week-old soybean seedlings were treated with 100 μM ABA, 5mM H2O2, 2mM SA, or 100 µM MeJA. Leaf samples were collected at indicated time points for total RNA isolation, and gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Values represent the means and standard errors of three replicates.

Promotion of flowering by GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in Arabidopsis

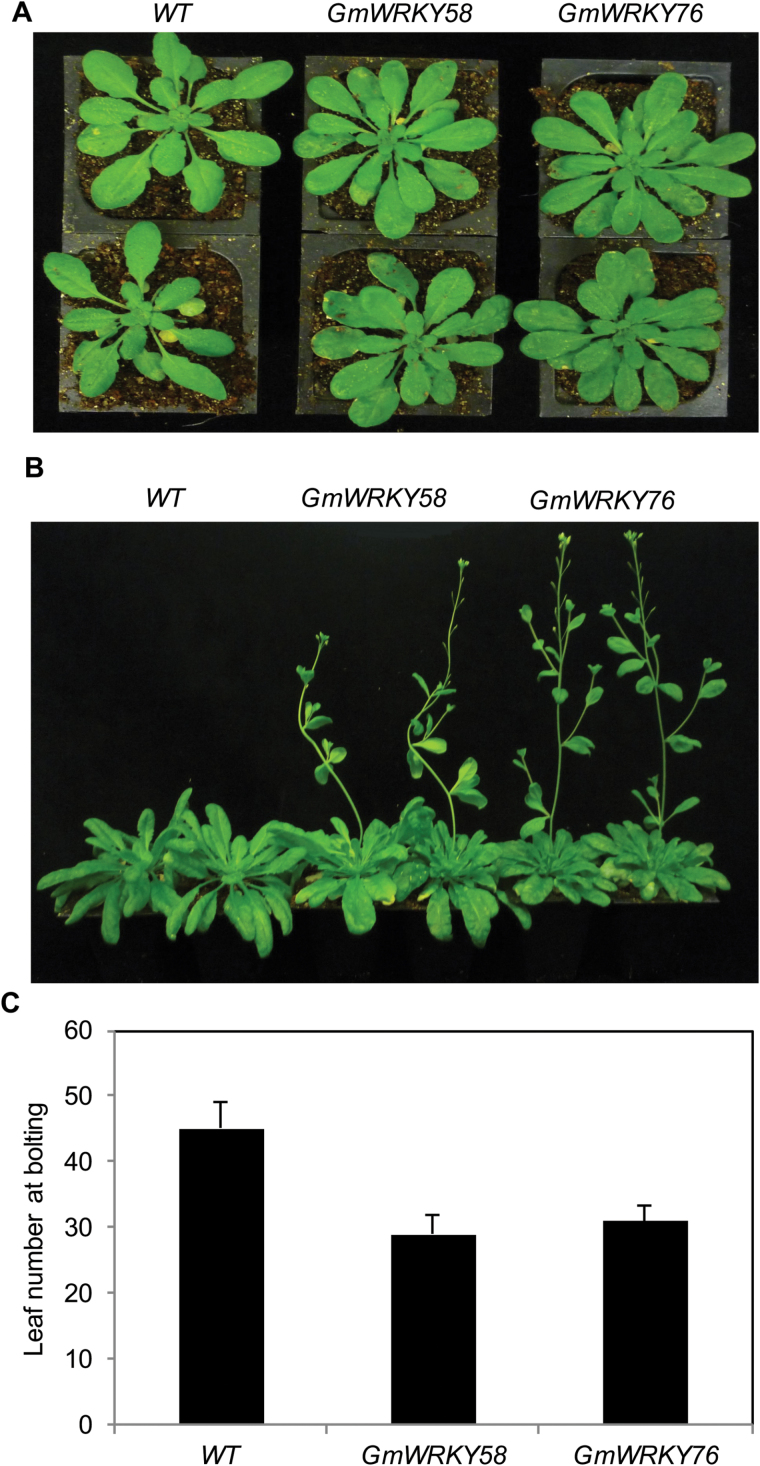

As described earlier, we were interested in functionally analyzing a large number of stress-responsive soybean WRKY genes through overexpression in Arabidopsis. Functional analysis of genes from crop plants, including soybean, through overexpression in Arabidopsis is a common and widely reported approach as the technique for transformation of the model plant is efficient and easy. In addition, many Arabidopsis WRKY genes have been well characterized and their close sequence similarity to many WRKY genes from soybean allows for comparative functional analysis. To analyze soybean WRKY genes in Arabidopsis, we first generated overexpression constructs of stress-responsive soybean WRKY genes under control of the constitutive and strong CaMV 35S promoter. Overexpression constructs for more than 60 stress-responsive soybean WRKY genes were then transformed into Arabidopsis using the floral-dip procedure and transformants were identified for their herbicide resistance. From independent transgenic Arabidopsis plants for each of >60 soybean WRKY genes examined at the same time, only those transgenic plants transformed with the GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 overexpression constructs flowered substantially earlier than the control plants. Because of the importance of this phenotype, these transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 plants were further characterized for possible alterations in growth, development, and stress responses. From the >10 independent transgenic plants for either of the two soybean WRKY genes, a majority of them had the early flowering phenotype and expressed high levels of the soybean WRKY transgenes based on qRT-PCR analysis (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Homozygous progeny containing a single transgene locus from these GmWRKY58- or GmWRKY76-expressing lines were subsequently obtained and used for phenotypic characterization. As shown in Fig. 8A, these transgenic GmWRKY58- or GmWRKY76-expressing plants grew mostly normally without major morphological abnormalities in the vegetative stages. However, these plants flowered substantially earlier than control plants (Fig. 8B). The numbers of leaves at the time of bolting in these transgenic plants were only about 60% of those in wild-type plants (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Overexpression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 and promotion of flowering in Arabidopsis. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 were identified by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1). Homozygous T3 progeny of transgenic GmWRKY58 (lines 3 and 4) and GmWRKY76 (lines 1 and 3) were grown at 12/12h light/dark photoperiod. Images of representative plants were taken at 6 (A) and 8 (B) weeks after germination. The rosette leaf numbers at bolting were counted from 30 plants of two independent lines for each transgene and are shown as means and standard errors (C).

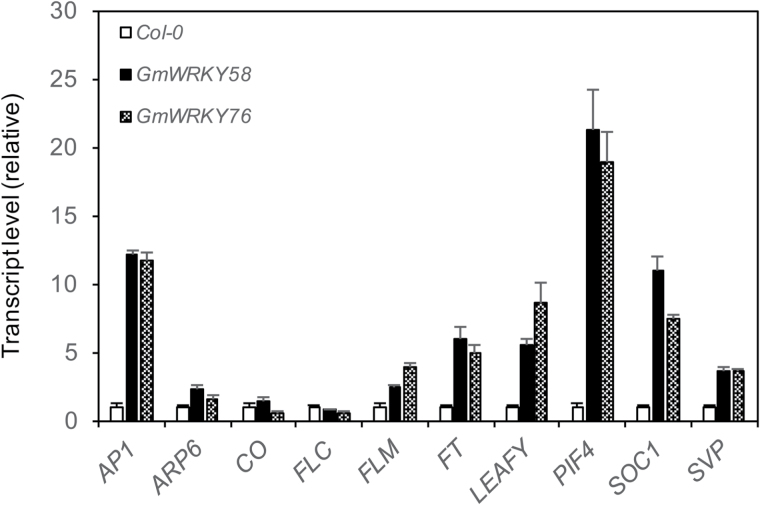

To determine the molecular basis for the early flowering phenotype of the transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 Arabidopsis plants, we compared them with control plants for expression of a range of flowering-time genes in 3-week-old seedlings. These flowering-time genes include both positive and negative regulators (e.g. FLC) of plant flowering. As shown in Fig. 9, we observed increased expression for many of the flowering-promoting genes in the transgenic plants when compared to that in control plants. These genes include AP1, FT, Leafy, PIF4, SOC1, and SVP1. On the other hand, transcript levels of the flowering-inhibiting gene FLC were not significantly altered, while those for FLM were only increased slightly in the transgenic plants (Fig. 9). Thus, increased expression of these flowering-promoting genes even in the very young seedlings is consistent with the early flowering phenotypes of the transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 overexpression plants.

Fig. 9.

Flowering-related gene expression in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. The leaf samples were collected from 3-week-old seedlings of control Col-0 and transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 plants for total RNA isolation. Expression of 10 flowering-related genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR using an Arabidopsis actin gene as an internal control. Values represent the means and standard errors of three replicates.

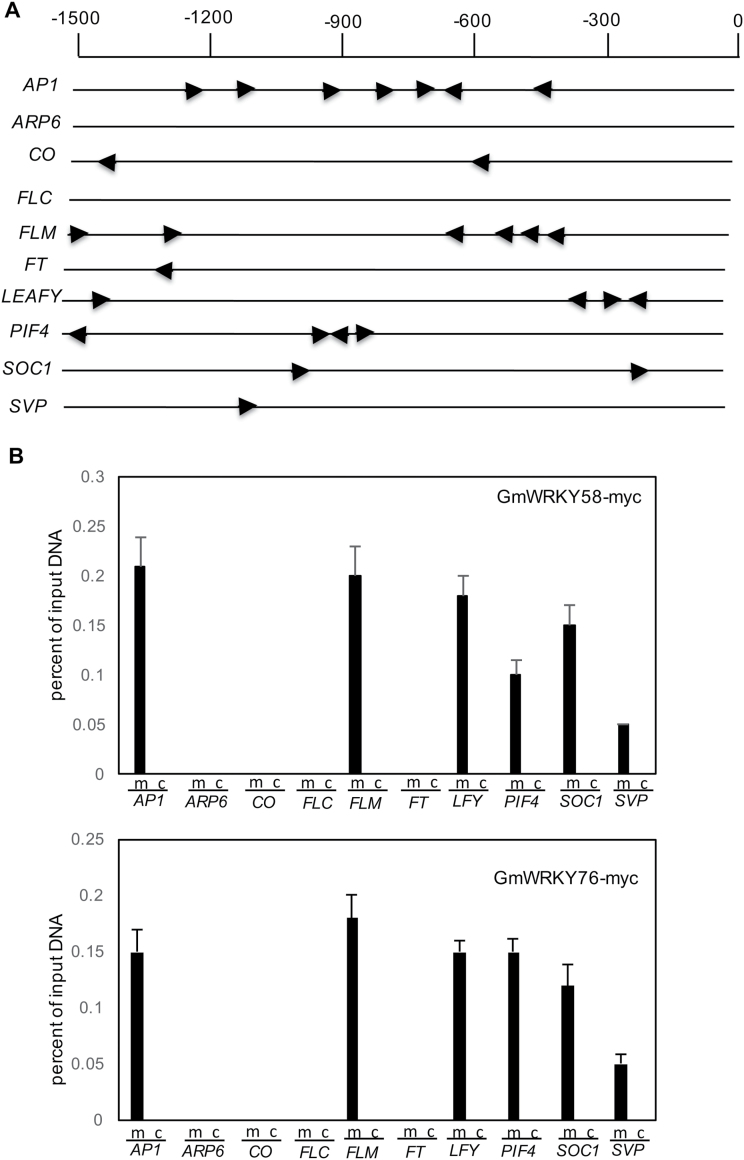

As DNA-binding transcription factors, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 promote flowering in transgenic plants most likely through regulation of transcription of genes that influence flowering either directly or indirectly. To determine the possibility of direct regulation of flowering-time genes by the two WRKY proteins, we examined the 1.5-kb region upstream of the translation start codon of these genes for the presence of the W-box sequences recognized by WRKY proteins. As shown in Fig. 10A, among the 10 flowering-time genes, only ARP6 and FLC contain no TTGAC W-box core sequence. For the remaining flowering-time genes, CO, FT, SOC1, and SVP contain only 1 to 2 W-box elements. The other four genes (AP1, FLM, LEAFY, and PIF4) contain 4 to 7 W-box elements in their 1.5-kb promoter region. Interestingly, there appeared to be a generally positive, although not perfect, correlation between the number of W-box elements and the extent of their induction in the transgenic plants. For example, ARP6 and FLC contain no W-box sequences and their expression was largely unaltered in the transgenic plants overexpressing GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. On the other hand, PIF4, AP1, and Leafy are three of the four flowering-time genes containing the highest numbers of W-box sequences in their promoters (Fig. 10A) and they also displayed the highest induction in transgenic plants overexpressing GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 (Fig. 9). These results suggest that GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 may directly regulate the expression of at least some of the flowering-time genes. To test this possibility, we performed a ChIP-qPCR assay to determine whether GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 bind to the promoters of some of these flowering-time genes. As shown in Fig. 10B, C, promoters of AP1, FLM, LFY, PIF4, SOC1, and SVP were substantially enriched with an anti-myc antibody that immunoprecipitates myc-tagged GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 transgene products in transfected Arabidopsis protoplasts. By contrast, the IgG control failed to immunoprecipitate the promoter DNA of the six flowering-time genes. On the other hand, no significant enrichment of the promoters of ARP6, CO, FLC, or FT was detected after immunoprecipitation with the anti-myc antibody or the IgG control.

Fig. 10.

Binding of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 to promoters of flowering-time genes. (A) W-box elements in the promoters of Arabidopsis flowering-related genes. Each W-box sequence (TTGAC) in the 1.5-kb promoter regions of the flowering-related genes is indicated with an arrow. Numbering is from the predicted translation start codons. (B, C) Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts were transfected with the 35S::GmWRKY58-4myc or 35S::GmWRKY76-4myc constructs. myc-Tagged GmWRKY-chromatin complexes were immunoprecipitated with an anti-myc antibody (m). A control reaction was processed side-by-side using mouse IgG (c). ChIP and input-DNA samples were quantified by real-time qPCR using primers specific to the promoters of the indicated flowering-time genes. The ChIP results are shown as a percentage of input DNA. Values represent the means and standard errors of three replicates.

Effects on disease resistance and stress tolerance by GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in Arabidopsis

Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 has been extensively analyzed in plant defense responses. Analysis using both loss-of-function mutants and overexpression lines revealed that AtWRKY70 promotes SA-dependent defense pathways but suppresses JA-dependent signaling (Li et al., 2004, 2006; Hu et al., 2012; Shim and Choi, 2013; Shim et al., 2013). To determine whether overexpression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 altered plant defense in transgenic plants, we analyzed the responses of Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the soybean WRKY genes to the virulent bacterial pathogen PstDC3000. A large number of studies have shown that Arabidopsis resistance to the virulent bacterial pathogen is dependent on SA signaling (Dong, 1998). When inoculated with the virulent bacteria, however, these transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 plants developed disease symptoms and supported bacterial growth at levels similar to those in control wild-type plants (see Supplementary Fig. S2). By contrast, the SA-signaling mutant npr1 developed more severe disease symptoms and supported higher levels of bacterial growth when inoculated with the same virulent bacteria (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, overexpression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 did not affect SA-dependent defense against the bacterial pathogen in Arabidopsis plants.

Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 and its close homolog AtWRKY54 also modulate plant osmotic stress (Li et al., 2013): both genes are induced by osmotic stress. Based on the assays using watering with 15% polyethylene glycol (PEG), it has been further found that the atwrky70 and atwrky54 mutant plants were more tolerant to osmotic stress (Li et al., 2013). Likewise, expression of both GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 was responsive to ABA (Fig. 7), a phytohormone with an important role in plant stress responses. To determine further the roles of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in plants suffering from osmotic stress, we analyzed whether responses were affected by their overexpression. As previously described, we subjected the transgenic plants to osmotic stress by watering with 15% PEG6000 for 3 d, but observed no significant difference in the development of wilting symptoms between the overexpression lines and control wild-type plants (data not shown). There was no significant difference either in electrolyte leakage assayed on leaves after exposure to 15% PEG for 1 and 3 d (data not shown). We also compared their germination rates with those of control wild-type plants in response to salt (150mM NaCl), osmotic stress (300mM mannitol), and ABA (1 µM). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, no significant effects of overexpression of the two soybean WRKY genes on germination were observed in the presence of 300mM mannitol. On the other hand, during the first 2 d after sowing, seeds of the GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-overexpressing plants germinated at significantly higher rates than control plants in the presence of 150mM NaCl, but at lower rates in the presence of 1 µM ABA (see Supplementary Fig. S3). These differences, however, largely disappeared during the 3rd and 4th days. Thus, the effects of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 on disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance were relatively small.

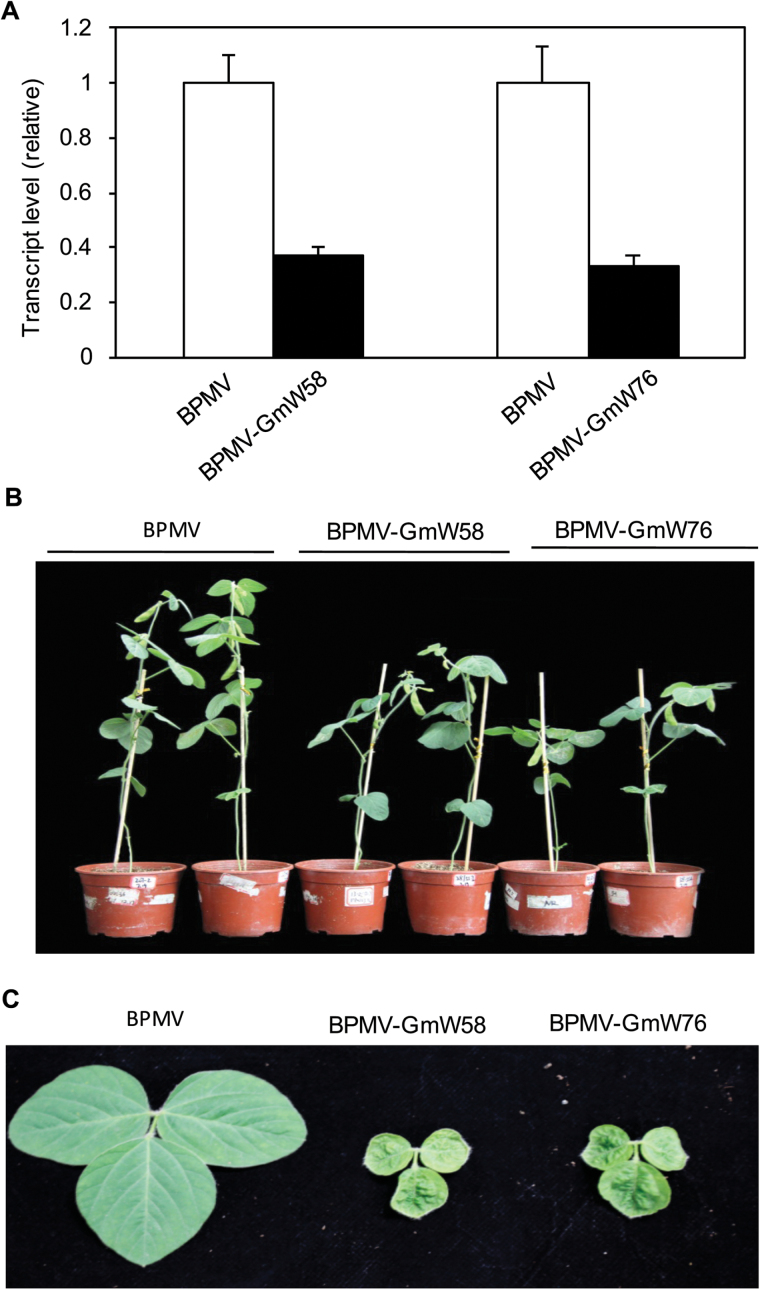

Stunted growth of soybean plants caused by silencing of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76

Unlike Arabidopsis, many plants including important crop species such as soybean are still relatively difficult to routinely and reliably transform. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) provides an alternative approach for targeted down-regulation and functional analysis of genes. VIGS mediated by Bean pod mottle virus (BPMV) has been successfully used in the functional investigation of soybean genes involved in defense and other processes, including soybean MAPK4 (GmMPK4) (Liu et al., 2011). To determine the role of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in soybean, we attempted to silence their gene expression using BPMV-mediated gene silencing. Gene fragments from GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 were separately cloned into the BPMV silencing vector and the viral vectors were delivered into soybean plants through particle bombardment. To determine the extent of silencing, we performed qRT-PCR of the transcript levels of the two soybean WRKY genes in inoculated plants. As shown in Fig. 11A, when compared to the plants inoculated with empty vectors, those inoculated with either GmWRKY58- or GmWRKY76-silencing vectors displayed a reduction of approximately 60% in the transcript levels of the targeted gene but also of the close homolog as well. As described earlier, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 share a high nucleotide sequence identify (>90%) and as a result either the construct for silencing GmWRKY58 or for silencing GmWRKY76 can silence both genes. Plants in which GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 were silenced had consistent phenotypes characterized by stunted growth (Fig. 11B). The soybean cultivar used in the experiments (‘Williams 82’) is a Group III indeterminate variety. Under the growth conditions with 12/12h photoperiod, the control plants maintained vegetative growth even after flowering and pod setting. Those plants inoculated with GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-silencing vectors were normal during the first 3–4 weeks after inoculation. However, around 4 weeks after inoculation, those plants with severe silencing of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 started to display stunted phenotypes characterized by slower emergence and smaller size of new leaves and shorter length of upper parts of the elongating stems (Fig. 11B, 11C). As a result, the stature of the upper part of plants with GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 silenced was substantially reduced, almost mimicking a determinate growth pattern, even though the stature of their lower parts was largely normal, with normal-sized leaves and pods.

Fig. 11.

Silencing of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 caused stunted growth. Expression of GmWRKY Y58 and GmWRKY76 was performed by qRT-PCR using a soybean actin gene as control (A). The results shown are from five individual GmWRKY58-silenced (BPMV-GmWRKY58) and GmWRKY76-silenced plants (BPMV-GmWRKY76) and empty BPMV vector control plants (BPMV-0). The pictures of representative plants (B) and trifoliate leaves (C) inoculated with empty vector (BPMV) or silencing BPMV-GmWRKY58 and BPMV-GmWRKY76 vectors were taken 7 weeks after inoculation. Some leaves were collected for RNA isolation, leaving only petioles in some plants shown in (B).

Discussion

As a large superfamily of plant transcription factors, WRKY proteins have been subjected to extensive functional analysis over the last two decades. The overwhelming majority of these studies have focused on the roles of WRKY transcription factors in broad plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. By contrast, a broad role of WRKY proteins in plant growth and development has not emerged, although a few WRKY proteins have been shown to play roles in certain specific plant developmental processes (Johnson et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2005, 2013; Li et al., 2015). In the present study, we have provided strong evidence that two closely related soybean WRKY proteins, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, have a critical role in plant growth and development. Even though they are close homologs of Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54, overexpression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 did not result in altered resistance to the bacterial pathogen P. syringae (see Supplementary Fig. S2) or in tolerance to osmotic stress – two phenotypes previously established for AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 (Li et al., 2004, 2006; Hu et al., 2012; Shim and Choi, 2013; Shim et al., 2013). The effects of their overexpression on tolerance to salt and osmotic stress and sensitivity to ABA were also negligible, or relatively small and transient (Supplementary Fig. S3). On the other hand, transgenic plants overexpressing GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 flowered substantially earlier than control plants (Fig. 8), a phenotype not observed in AtWRKY70- and AtWRKY54-overexpressing plants. Furthermore, silencing of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 led to stunted plants characterized by greatly inhibited growth of expanding leaves and elongating stems (Fig. 11). These results establish that these two closely related WRKY proteins play an important and specific role in plant growth and development.

In Arabidopsis, overexpressing of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 had strong effects on flowering time but had no significance on vegetative growth such as leaf expansion (Fig. 8). On the other hand, silencing of the same soybean WRKY genes in soybean mostly affected the growth of vegetative organs (leaves and stems) (Fig. 11). This discrepancy of phenotypes could be due to the fact that the phenotypes in Arabidopsis resulted from the gain-of-function overexpression approach whilst those in soybean were from a loss-of-function approach through down-regulation of the targeted genes. The phenotypes of transgenic plants overexpressing a gene of interest are mostly likely indicative of the potential functions of the gene when it is expressed at high levels. On the other hand, the phenotypes of loss-of-function mutants or gene-silencing plants are more indicative of the biological functions of the gene when expressed at physiological levels. The discrepancy of phenotypes could also be due to differences between Arabidopsis and soybean in important aspects of growth and development. For example, when Arabidopsis plants switch from a vegetative to reproductive state, it leads to the formation of an inflorescence with a cluster of flowers arranged on the stem. On the other hand, when soybean cultivars such as ‘Williams 82’ used in our VIGS experiments start flowering, the shoot apical meristem remains vegetative, where it further regulates the production of lateral vegetative and reproductive growth (Tian et al., 2010; Ping et al., 2014). It is possible that GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are capable of promoting the activity of terminal meristems, which in Arabidopsis could lead to earlier transition from vegetative growth to flowering. On the other hand, since terminal meristems of soybean remain vegetative even after flowers have already developed from the buds at the base, silencing of genes important for the activity of terminal meristems may primarily lead to compromised vegetative growth, causing stunted phenotypes as observed in GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-silenced soybean plants (Fig. 11). It should also be pointed that plant growth and development are functionally and mechanistically closely linked. Many factors including a variety of environmental cues and hormones can affect both growth and development. GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 could regulate certain genes with roles in both growth and development, but there might be differential effects of these genes in different plants due to differences in the regulation pathways and/or in the physiological states that affect growth and development.

As transcription factors, the critical roles of WRKY proteins in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses are mediated through their regulation of the transcription of a large number of genes involved in stress responses. Indeed, genes differentially regulated during the activation of plant defense responses such as SA-mediated systemic-acquired resistance are substantially enriched in the W-box sequences in their promoters (Maleck et al., 2000). Both GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 bind W-box sequences (Fig. 3), act as transcriptional activators in both yeast and plant cells (Fig. 4), and are localized in the nucleus (Fig. 5). These properties make it highly likely that they positively regulate plant growth and development through transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Since both these WRKY proteins promote flowering in transgenic Arabidopsis, some of their potential target genes could be those controlling flowering. Indeed, earlier flowering of the transgenic GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-overexpressing plants was associated with increased expression of positive regulators of flowering including AP1, FT, Leafy, PIF4, SOC1, and SVP1 (Fig. 9). A survey revealed the presence of W-box sequences in the promoters of all these flowering-promoting genes (Fig. 10A). The presence of a large number of W-box sequences in the promoters of some of these important flowering-controlling genes, including AP1, LEAFY, FLM, and PIF4, was also associated with their increased expression in the transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 plants (Figs 9 and 10A). In contrast, FLC and ARP6 contain no W-box sequences in their promoter regions and they were not significantly altered in expression in the transgenic GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 plants (Figs 9 and 10A). ChIP-qPCR assays showed that GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 bind to promoters of some flowering-time genes (Fig. 10B, C), suggesting their direct regulation by the two WRKY proteins. Notably, FLM, an inhibitor of flowering, and PIF4, a positive regulator of flowering, have been established to play critical roles in induction of flowering by certain environmental conditions such as elevated temperature (Lee et al., 2013). Enrichment of W-box sequences in the promoters of both positive and negative regulators of plant flowering raises the possibility of a potentially complex network of regulation of flowering-time genes by WRKY proteins that could contribute to altered flowering time under stress conditions.

In soybean, GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are differentially expressed at different stages of leaf growth. The expression of the two genes is at low levels in both early and late stages of leaf development, but they are expressed at substantially elevated levels during the stages of leaves expansion (Fig. 6). This expression pattern for GmWRKY58 and GMWRKY76 is consistent with their critical role as positive regulators of leaf growth based on the severely stunted leaves of GmWRKY58- and GMWRKY76-silenced soybean plants (Fig. 11). Thus, there appears to be a transcriptional cascade in which GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 are first activated in response to unknown developmental cues. Based on the highly responsive nature of both GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 to H2O2, cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) or redox state, which are known to function as signals not only for stress responses but also growth and development (Ren et al., 2002; Das and Maulik, 2003, 2004; Gill and Tuteja, 2010), could function as possible cellular cues for developmentally regulated expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76. GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-silenced soybean plants were stunted not only in leaf growth but also in overall plant status due to inhibited stem growth. Soybean stem growth habit is a critical adaptation and agronomic trait (Tian et al., 2010; Ping et al., 2014). The termination of soybean apical stem growth leads to a determinate stem upon the onset of floral induction of the shoot apical meristem (Tian et al., 2010; Ping et al., 2014). Although the molecular basis for determining the soybean stem growth habit has not been fully established, recent studies have identified a number of genes that are important in its control. Importantly, some of the genes identified, including Dt1 and Dt2, which determine soybean stem growth habit, are homologous to Arabidopsis flowering-time/flower development genes (Tian et al., 2010; Ping et al., 2014). Therefore, potential soybean target genes of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 may include those that regulate the growth or fate of the apical meristem, similar to those well-established flowering-time genes in Arabidopsis.

Despite their close similarity in protein sequences, overexpression of AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 does not significantly alter flowering time in transgenic plants. In addition, atwrky70 atwrky54 mutants are normal in plant growth, morphology, and development. By contrast, overexpression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in Arabidopsis altered flowering time (Fig. 8) but did not have major effects on plant disease resistance or abiotic stress tolerance (see Supplemental Figs 2 and 3). Thus despite their structural similarity, the biological functions of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 have diverged from those of AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54. In fact, almost all analyzed WRKY proteins recognize the TTGACC/T W-boxes in vitro but often have different biological functions. This is probably due to a number of important reasons. First, different WRKY proteins may have significant or subtle differences in their DNA-binding specificity and affinity, which has been demonstrated for even closely related WRKY proteins through in vitro assays using DNA molecules that differ not only in the TTGACC/T W-box consensus sequences but also in the flanking sequences (Brand et al., 2010, 2013). Second, even for those WRKY proteins with the same binding specificity and affinity in vitro, their in vivo DNA-binding properties could differ significantly. This is because in vitro binding assays usually use naked DNA probes. In vivo, however, the chromosomal DNA is packaged around histone proteins to form nucleosomes, the fundamental repeating units of eukaryotic chromatin. As a result, a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein may not have access to its in vivo genomic targets if they are occupied by nucleosomes. In a previously published study, it has been shown that the NF1 transcription factor from Caenorhabditis elegans recognizes the TTGGCA(N)3TGCCAA consensus sequence in vitro (Whittle et al., 2009). This sequence occurs 586 times in the genome of C. elegans but ChIP assays identified only 55 genomic binding sites of NF1(Whittle et al., 2009). The reason why GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 could bind to the W-box elements of the flowering-time gene promoters could be due to their WRKY-domain-flanking sequences that directly or indirectly affect chromatin remodeling and nucleosome phasing. Third, depending on the protein sequences flanking the DNA-binding domains, different WRKY transcription factors can function as transcriptional activators or repressors and as a result can play different biological functions. Therefore, the biological function of a WRKY transcription factor is determined not only by its highly conserved WRKY DNA-binding domain but also by its other functional domains or motifs that dictate or modulate its access to genomic targets and transcriptional activity. Finally, differential expression patterns of different WRKY genes and post-translational modification of their products could also affect their biological functions. Indeed, we have recently compared Arabidopsis AtWRKY33 and AtWRKY25 for their differential roles in plant disease resistance and stress tolerance (Zhou et al., 2015). Unlike AtWRKY25, AtWRKY33 plays a critical role in plant resistance to necrotrophic pathogens based on the analysis of both overexpression lines and knockout mutants (Zheng et al., 2006; Lai et al., 2011; Merz et al., 2015). Through molecular complementation of the atwrky33 mutants using mutated or truncated WRKY gene constructs, we have discovered that both the extended C-terminal domain and its stronger pathogen-responsive promoter are important for the critical role of AtWRKY33 in plant defense against necrotrophic pathogens (Zhou et al., 2015). Likewise, Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 share high sequence identify with soybean GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, not only in the conserved WRKY domains but also in the N-terminal region (Fig. 1). On the other hand, their C-terminal regions are relatively divergent (Fig. 1) and might be responsible for their distinct biological functions. Through structural and functional dissection of close WRKY homologs such as Arabidopsis AtWRKY70 and AtWRKY54 and soybean GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76, it should be possible to identify important protein sequences and DNA/RNA elements critical for the distinct biological functions of WRKY proteins. This knowledge will lead to a better understanding of not only the complex mode of action of WRKY transcription factors but also the fundamental regulatory mechanisms of plant growth, development, and responses to environmental conditions.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. Expression of GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants.

Figure S2. Response of transgenic GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants to Pseudomonas syringae.

Figure S3. Germination rates of transgenic GmWRKY58- and GmWRKY76-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants.

Table S1. Arabidopsis, soybean, and rice Group III WRKY proteins used in the phylogenetic analysis.

Table S2. Primers used in qRT-PCR.

Table S3. Primers used in ChIP-qPCR.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs Chunquan Zhang and Steven Whitham for the BPMV VIGS vectors and Dr Lan-Ying Lee for advice on protoplast isolation using the tape-Arabidopsis sandwich procedure. This work is supported by the China Ministry of Agriculture Transgenic Crop Major Project (grant no. 2012ZX08009004), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2013M531466), the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant no. IOS1456300), and an AgSEED grant from Purdue University.

References

- Aoyama T, Chua N-H. 1997. A glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. The Plant Journal 11, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besseau S, Li J, Palva ET. 2012. WRKY54 and WRKY70 co-operate as negative regulators of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana . Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 2667–2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand LH, Fischer NM, Harter K, Kohlbacher O, Wanke D. 2013. Elucidating the evolutionary conserved DNA-binding specificities of WRKY transcription factors by molecular dynamics and in vitro binding assays. Nucleic Acids Research 41, 9764–9778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand LH, Kirchler T, Hummel S, Chaban C, Wanke D. 2010. DPI-ELISA: a fast and versatile method to specify the binding of plant transcription factors to DNA in vitro. Plant Methods 6, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen Z. 2000. Isolation and characterization of two pathogen- and salicylic acid- induced genes encoding WRKY DNA-binding proteins from tobacco. Plant Molecular Biology 42, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen Z. 2002. Potentiation of developmentally regulated plant defense response by AtWRKY18, a pathogen-induced Arabidopsis transcription factor. Plant Physiology 129, 706–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Zhang L, Li D, Wang F, Yu D. 2013. WRKY8 transcription factor functions in the TMV-cg defense response by mediating both abscisic acid and ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 1963–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. 1998. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das DK, Maulik N. 2003. Preconditioning potentiates redox signaling and converts death signal into survival signal. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 420, 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das DK, Maulik N. 2004. Conversion of death signal into survival signal by redox signaling. Biochemistry (Moscow) 69, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding ZJ, Yan JY, Li CX, Li GX, Wu YR, Zheng SJ. 2015. Transcription factor WRKY46 modulates the development of Arabidopsis lateral roots in osmotic/salt stress conditions via regulation of ABA signaling and auxin homeostasis. The Plant Journal 84, 56–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding ZJ, Yan JY, Xu XY, Li GX, Zheng SJ. 2013. WRKY46 functions as a transcriptional repressor of ALMT1, regulating aluminum-induced malate secretion in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 76, 825–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding ZJ, Yan JY, Xu XY, Yu DQ, Li GX, Zhang SQ, Zheng SJ. 2014. Transcription factor WRKY46 regulates osmotic stress responses and stomatal movement independently in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 79, 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Chen C, Chen Z. 2003. Expression profile of the Arabidopsis WRKY gene superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Molecular Biology 51, 21–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. 1998. SA, JA, ethylene, and disease resistance in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 1, 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T. 2006. Dissecting the WRKY web of plant defense regulators. PLoS Pathogens 2, e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. 2000. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends in Plant Science 5, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Somssich IE. 2007. Networks of WRKY transcription factors in defense signaling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 10, 366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Tuteja N. 2010. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48, 909–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Chen L, Wang H, Zhang L, Wang F, Yu D. 2013. Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY8 functions antagonistically with its interacting partner VQ9 to modulate salinity stress tolerance. The Plant Journal 74, 730–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Dong Q, Yu D. 2012. Arabidopsis WRKY46 coordinates with WRKY70 and WRKY53 in basal resistance against pathogen Pseudomonas syringae . Plant Science 185–186, 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Yu D. 2009. Arabidopsis WRKY2 transcription factor mediates seed germination and postgermination arrest of development by abscisic acid. BMC Plant Biology 9, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Liang G, Yang S, Yu D. 2014. Arabidopsis WRKY57 functions as a node of convergence for jasmonic acid- and auxin-mediated signaling in jasmonic acid-induced leaf senescence. The Plant Cell 26, 230–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Liang G, Yu D. 2012. Activated expression of WRKY57 confers drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant 5, 1375–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CS, Kolevski B, Smyth DR. 2002. TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2, a trichome and seed coat development gene of Arabidopsis, encodes a WRKY transcription factor. The Plant Cell 14, 1359–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Dangl JL. 2006. The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC, Fan B, Chen Z. 2006. Pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY7 is a transcriptional repressor and enhances plant susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringae . Plant Physiology 142, 1180–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC, Lai Z, Fan B, Chen Z. 2008. Arabidopsis WRKY38 and WRKY62 transcription factors interact with histone deacetylase 19 in basal defense. The Plant Cell 20, 2357–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoth C, Ringler J, Dangl JL, Eulgem T. 2007. Arabidopsis WRKY70 is required for full RPP4-mediated disease resistance and basal defense against Hyaloperonospora parasitica . Molecular Plant-Microbe Interaction 20, 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Z, Li Y, Wang F, Cheng Y, Fan B, Yu JQ, Chen Z. 2011. Arabidopsis sigma factor binding proteins are activators of the WRKY33 transcription factor in plant defense. The Plant Cell 23, 3824–3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Z, Vinod KM, Zheng Z, Fan B, Chen Z. 2008. Roles of Arabidopsis WRKY3 and WRKY4 transcription factors in plant responses to pathogens. BMC Plant Biology 8, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Ryu HS, Chung KS, Pose D, Kim S, Schmid M, Ahn JH. 2013. Regulation of temperature-responsive flowering by MADS-box transcription factor repressors. Science 342, 628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Besseau S, Toronen P, Sipari N, Kollist H, Holm L, Palva ET. 2013. Defense-related transcription factors WRKY70 and WRKY54 modulate osmotic stress tolerance by regulating stomatal aperture in Arabidopsis. The New Phytologist 200, 457–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Brader G, Kariola T, Palva ET. 2006. WRKY70 modulates the selection of signaling pathways in plant defense. The Plant Journal 46, 477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Brader G, Palva ET. 2004. The WRKY70 transcription factor: a node of convergence for jasmonate-mediated and salicylate-mediated signals in plant defense. The Plant Cell 16, 319–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Tian Z, Yu D. 2015. WRKY13 acts in stem development in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Science 236, 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JZ, Horstman HD, Braun E, et al. 2011. Soybean homologs of MPK4 negatively regulate defense responses and positively regulate growth and development. Plant Physiology 157, 1363–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Dennis ES, Berger F, Peacock WJ, Chaudhury A. 2005. MINISEED3 (MINI3), a WRKY family gene, and HAIKU2 (IKU2), a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) KINASE gene, are regulators of seed size in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 102, 17531–17536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Sun X, Liu B, et al. 2013. Ectopic expression of a WRKY homolog from Glycine soja alters flowering time in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 8, e73295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleck K, Levine A, Eulgem T, Morgan A, Schmid J, Lawton KA, Dangl JL, Dietrich RA. 2000. The transcriptome of Arabidopsis thaliana during systemic acquired resistance. Nature Genetics 26, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao G, Meng X, Liu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Z, Zhang S. 2011. Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by two pathogen-responsive MAPKs drives phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 23, 1639–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz PR, Moser T, Holl J, Kortekamp A, Buchholz G, Zyprian E, Bogs J. 2015. The transcription factor VvWRKY33 is involved in the regulation of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) defense against the oomycete pathogen Plasmopara viticola . Physiologia Plantarum 153, 365–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y, Laun T, Zimmermann P, Zentgraf U. 2004. Targets of the WRKY53 transcription factor and its role during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Molecular Biology 55, 853–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SP, Somssich IE. 2009. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity. Plant Physiology 150, 1648–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping J, Liu Y, Sun L, et al. 2014. Dt2 is a gain-of-function MADS-domain factor gene that specifies semideterminacy in soybean. The Plant Cell 26, 2831–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Yang H, Zhang S. 2002. Cell death mediated by MAPK is associated with hydrogen peroxide production in Arabidopsis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 277, 559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinerson CI, Rabara RC, Tripathi P, Shen QJ, Rushton PJ. 2015. The evolution of WRKY transcription factors. BMC Plant Biology 15, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek S, Somssich IE. 2002. Targets of AtWRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes & Development 16, 1139–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ. 2010. WRKY transcription factors. Trends in Plant Science 15, 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Yan L, Liu ZQ, et al. 2010. The Mg-chelatase H subunit of Arabidopsis antagonizes a group of WRKY transcription repressors to relieve ABA-responsive genes of inhibition. The Plant Cell 22, 1909–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JS, Choi YD. 2013. Direct regulation of WRKY70 by AtMYB44 in plant defense responses. Plant Signaling & Behavior 8, e20783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim JS, Jung C, Lee S, Min K, Lee YW, Choi Y, Lee JS, Song JT, Kim JK, Choi YD. 2013. AtMYB44 regulates WRKY70 expression and modulates antagonistic interaction between salicylic acid and jasmonic acid signaling. The Plant Journal 73, 483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Yu D. 2015. Activated expression of AtWRKY53 negatively regulates drought tolerance by mediating stomatal movement. Plant Cell Reports 34, 1295–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttipanta N, Pattanaik S, Kulshrestha M, Patra B, Singh SK, Yuan L. 2011. The transcription factor CrWRKY1 positively regulates the terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus . Plant Physiology 157, 2081–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Z, Wang X, Lee R, Li Y, Specht JE, Nelson RL, McClean PE, Qiu L, Ma J. 2010. Artificial selection for determinate growth habit in soybean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107, 8563–8568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Avci U, Nakashima J, Hahn MG, Chen F, Dixon RA. 2010. Mutation of WRKY transcription factors initiates pith secondary wall formation and increases stem biomass in dicotyledonous plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107, 22338–22343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle CM, Lazakovitch E, Gronostajski RM, Lieb JD. 2009. DNA-binding specificity and in vivo targets of Caenorhabditis elegans nuclear factor I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106, 12049–12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu FH, Shen SC, Lee LY, Lee SH, Chan MT, Lin CS. 2009. Tape-Arabidopsis sandwich – a simpler Arabidopsis protoplast isolation method. Plant Methods 5, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KL, Guo ZJ, Wang HH, Li J. 2005. The WRKY family of transcription factors in rice and Arabidopsis and their origins. DNA Research 12, 9–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Cheng H, Li X, Xu C, Wang S. 2013. Rice WRKY13 regulates cross talk between abiotic and biotic stress signaling pathways by selective binding to different cis-elements. Plant Physiology 163, 1868–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Chen C, Fan B, Chen Z. 2006. Physical and functional interactions between pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40, and WRKY60 transcription factors. The Plant Cell 18, 1310–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Xie Y, Raja P, Li S, Wolf JN, Shen Q, Bisaro DM, Zhou X. 2011. Suppression of methylation-mediated transcriptional gene silencing by betaC1-SAHH protein interaction during geminivirus-betasatellite infection. PLoS Pathogens 7, e1002329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Ligang C, Liping Z, Diqiu Y. 2010. Overexpression of OsWRKY72 gene interferes in the abscisic acid signal and auxin transport pathway of Arabidopsis. Journal of Biosciences 35, 459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Bradshaw JD, Whitham SA, Hill JH. 2010. The development of an efficient multipurpose bean pod mottle virus viral vector set for foreign gene expression and RNA silencing. Plant Physiology 153, 52–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Whitham SA, Hill JH. 2013. Virus-induced gene silencing in soybean and common bean. Methods in Molecular Biology 975, 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang L. 2005. The WRKY transcription factor superfamily: its origin in eukaryotes and expansion in plants. BMC Evolutionary Biology 5, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Mosher SL, Fan B, Klessig DF, Chen Z. 2007. Functional analysis of Arabidopsis WRKY25 transcription factor in plant defense against Pseudomonas syringae . BMC plant Biology 7, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Qamar SA, Chen Z, Mengiste T. 2006. Arabidopsis WRKY33 transcription factor is required for resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. The Plant Journal 48, 592–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang J, Zheng Z, Fan B, Yu JQ, Chen Z. 2015. Characterization of the promoter and extended C-terminal domain of Arabidopsis WRKY33 and functional analysis of tomato WRKY33 homologues in plant stress responses. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 4567–4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.