Abstract

Background

Fecal microbiota therapy is increasingly being used to treat patients with Clostridium difficile infection. This health technology assessment primarily evaluated the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of fecal microbiota therapy compared with the usual treatment (antibiotic therapy).

Methods

We performed a literature search using Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, CRD Health Technology Assessment Database, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and NHS Economic Evaluation Database. For the economic review, we applied economic filters to these search results. We also searched the websites of agencies for other health technology assessments.

We conducted a meta-analysis to analyze effectiveness. The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. Using a step-wise, structural methodology, we determined the overall quality to be high, moderate, low, or very low.

We used a survey to examine physicians’ perception of patients’ lived experience, and a modified grounded theory method to analyze information from the survey.

Results

For the review of clinical effectiveness, 16 of 1,173 citations met the inclusion criteria. A meta-analysis of two randomized controlled trials found that fecal microbiota therapy significantly improved diarrhea associated with recurrent C. difficile infection versus treatment with vancomycin (relative risk 3.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.85–5.68) (GRADE: moderate). While fecal microbiota therapy is not associated with a significant decrease in mortality compared with antibiotic therapy (relative risk 0.69, 95% CI 0.14–3.39) (GRADE: low), it is associated with a significant increase in adverse events (e.g., short-term diarrhea, relative risk 30.76, 95% CI 4.46–212.44; abdominal cramping, relative risk 14.81, 95% CI 2.07–105.97) (GRADE: low).

For the value-for-money component, two of 151 economic evaluations met the inclusion criteria. One reported that fecal microbiota therapy was dominant (more effective and less expensive) compared with vancomycin; the other reported an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $17,016 USD per quality-adjusted life-year for fecal microbiota therapy compared with vancomycin. This ratio for the second study indicated that there would be additional cost associated with each recurrent C. difficile infection resolved. In Ontario, if fecal microbiota therapy were adopted to treat recurrent C. difficile infection, considering it from the perspective of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care as the payer, an estimated $1.5 million would be saved after the first year of adoption and $2.9 million after 3 years. The contradiction between the second economic evaluation and the savings we estimated may be a result of the lower cost of fecal microbiota therapy and hospitalization in Ontario compared with the cost of therapy used in the US model.

Physicians reported that C. difficile infection significantly reduced patients’ quality of life. Physicians saw fecal microbiota therapy as improving patients’ quality of life because patients could resume daily activities. Physicians reported that their patients were happy with the procedures required to receive fecal microbiota therapy.

Conclusions

In patients with recurrent C. difficile infection, fecal microbiota therapy improves outcomes that are important to patients and provides good value for money.

BACKGROUND

Clinical Need and Target Population

The incidence of Clostridium difficile infection has increased by about 20 times over the past 10 years, and rates are about 20 per 100,000 population.1 Risk factors for infection include antibiotic use, inflammatory bowel disease, comorbidity, and increasing age.1 About 20% to 30% of patients treated for an initial episode have a recurrence, and 40% to 60% of those patients have subsequent (second or later) recurrences.2 In severe cases, C. difficile infection can result in bowel perforation and, rarely, death.2

Antibiotics used for C. difficile infection are metronidazole as first-line and vancomycin as second-line therapies.1 In some cases, patients unresponsive to medical management are treated by surgical colectomy.3

Technology

Fecal microbiota therapy is increasingly used as a treatment for C. difficile infection in the belief that importing the colonic microbiome of a healthy person is a simple way to reconstitute the normal colonic flora (microorganisms that live in the gut).3

The routes of fecal microbiota administration vary in the literature (e.g., enema, upper gastrointestinal tract route, colonoscopy). The timing and frequency of fecal microbiota therapy also vary, from a single session to serial administration over several days.3

Regulatory Information

A Health Canada Guidance document (March 2015)4 considers fecal microbiota therapy a biologic drug and states the following:

Health Canada is notifying stakeholders of its risk based, provisional interpretation regarding the Clinical Trial Application (CTA) requirements in the Food and Drug Regulations for the use of Fecal Microbiota Therapy (FMT) by health care practitioners to treat patients with recurrent CDI [C. difficile infection] not responsive to conventional therapies … This interim policy allows health care practitioners to treat patients suffering from CDI not responsive to conventional therapies with FMT without a clinical trial where the conditions in this guidance document are followed … Effective immediately, this provisional interpretation regarding the CTA requirements will be applied on an interim basis while the Department continues to explore future policy options for regulating FMT.

Health Canada's 2015 guidance for fecal microbiota therapy4 replicates the United States Food and Drug Administration's 2013 enforcement policy5 regarding investigational new drug requirements for the use of fecal microbiota therapy to treat C. difficile infection that is unresponsive to standard therapies.

Context

At least three centres in Ontario perform fecal microbiota therapy for C. difficile infection (University Health Network, St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton, and Toronto East General Hospital).

Based on referral experience, an expert estimated that about 500 to 1,000 patients per year in Ontario would be eligible to receive fecal microbiota therapy for recurrent C. difficile infection (C. Lee, written communication, October 27, 2015).

Research Question

What are the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and budgetary impact of fecal microbiota therapy compared with antibiotics in adults with initial, recurrent, or refractory C. difficile infections?

CLINICAL EVIDENCE REVIEW

Objective

The clinical evidence section of the health technology assessment reviewed the effectiveness of fecal microbiota therapy compared with antibiotics in adults with initial or recurrent C. difficile infection.

Methods

Research questions are developed by Health Quality Ontario in consultation with experts and applicants in the topic area.

Sources

We performed a literature search on July 30, 2015, using Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Health Technology Assessment Database, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database, for studies published from January 1, 2013, to July 30, 2015. A 2-year search was chosen because a recent, comprehensive systematic review was published in 2015.

Search strategies were developed by medical librarians using medical subject headings (MeSH). See Appendix 1 for full details, including all search terms.

Literature Screening

A single reviewer reviewed the abstracts, and we obtained full-text articles for studies meeting the eligibility criteria. We also examined reference lists for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published between January 1, 2013, and July 30, 2015

Randomized controlled trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses

Studies of fecal microbiota therapy (via variable routes of administration and variable timing and frequency) for C. difficile infection

Studies involving patients with initial, recurrent, or refractory C. difficile infection. Initial infection is defined as the first occurrence, recurrent infection as an episode occurring after one previous episode of treatment with a favourable response, and refractory infection as an episode that did not respond to treatment

Studies where the comparators were antibiotics

Exclusion Criteria

Animal and in vitro studies

Editorials, case reports, or commentaries

Studies of fecal microbiota therapy for indications other than C. difficile infection

Outcomes of Interest

Resolution of symptoms

Quality of life

Mortality

Adverse events

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on study characteristics, risk of bias items, and PICO (population, intervention, comparison, and outcome) using a standardized data form. The form collected information about:

Source (i.e., citation information, contact details, study type)

Methods (i.e., study design, study duration and years, participant allocation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding, reporting of missing data, reporting of outcomes, and whether the study compared two or more groups)

Outcomes (i.e., outcomes measured, number of participants for each outcome, number of participants missing for each outcome, outcome definition and source of information, unit of measurement, upper and lower limits [for scales], and time points at which the outcome was assessed)

We contacted the authors of the studies to provide unpublished data when required for comparisons and meta-analysis.

Statistical Analysis

An analysis of individual studies was performed using Review Manager, version 5.6 Summary measures were expressed as the mean difference for continuous data and risk difference for dichotomous data using the Mantel-Haenszel method. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the chi-square test. A P value ≤ .10 associated with a chi-square statistic was considered substantial heterogeneity, and a random effects model was used. In the case of zero events, 1.0 was added to both groups. Graphic display of the forest plots was also examined. A P value ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant for overall effect estimate.

Quality of Evidence

We used the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) measurement tool to assess the methodologic quality of systematic reviews.7 See Appendix 2 for details of the AMSTAR analysis.

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria.8 The overall quality was determined to be high, moderate, low, or very low using a step-wise, structural methodology.

Results

Literature Search

The database search yielded 1,173 citations published between January 1, 2013, and July 30, 2015. After removing duplicates, we reviewed titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles. We obtained the full texts of these articles for further assessment. Sixteen studies (nine systematic reviews, six observational studies, and one randomized controlled trial [RCT]) met the inclusion criteria. We hand-searched reference lists of the included studies, along with health technology assessment websites and other sources, to identify additional relevant studies. No further citations were added.

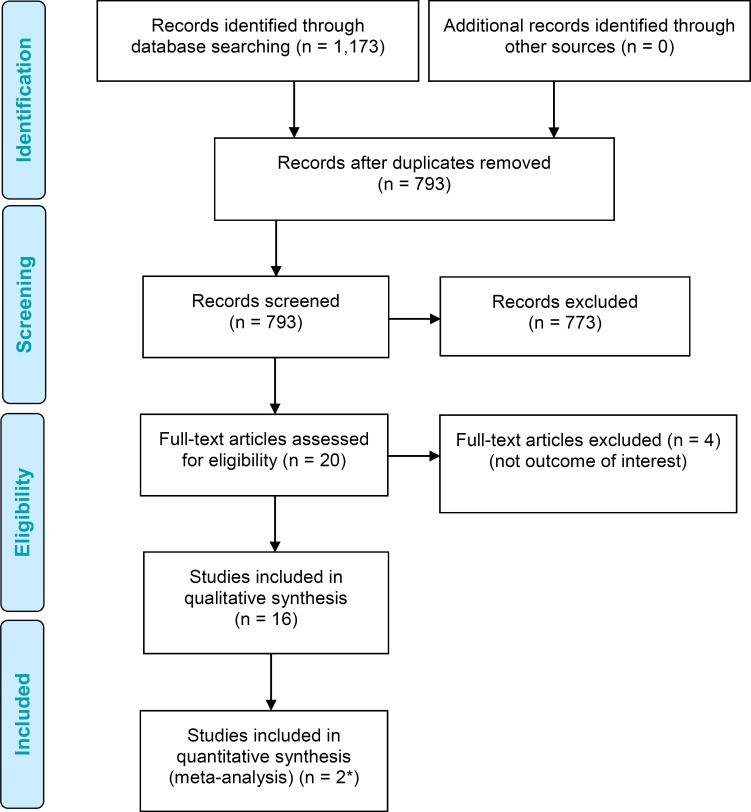

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Figure 1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Flow Diagram.

*Incorporates one study that was already included in the systematic review by Drekonja et al.3

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.9

Methodologic Quality of Included Studies

Results of the methodology checklist for included studies are presented in Appendix 2.

The AMSTAR scores for the nine systematic reviews are shown in Table A1.

One RCT10 and six observational studies11–16 were published after the literature search cut-off date (January 2015) used in the most recent systematic review by Drekonja et al.3

Systematic Review

The most recent (2015) systematic review by Drekonja et al3 defined initial infection as the first occurrence, recurrent infection as an episode occurring after one previous episode of treatment with a favourable response, and refractory infection as an episode that does not respond to treatment. The primary outcome of interest was the resolution of symptoms after a single treatment of fecal microbiota, or after a single prespecified series of treatments.3 Drekonja et al3 identified two RCTs and 28 case series for recurrent C. difficile infection. A meta-analysis was not completed, and results were reported narratively. The overall quality of the available evidence evaluating fecal microbiota therapy is low.3

Results of the systematic review are reported in Appendix 4. In summary, the authors concluded that, for recurrent C. difficile infection,3 fecal microbiota therapy could have a substantial effect with few short-term adverse events. However, evidence was insufficient about the use of fecal microbiota therapy for refractory or initial C. difficile treatment, and about whether effects vary by donor, preparation, or delivery method.3 Transient adverse events attributed to fecal microbiota therapy—including diarrhea, cramping, belching, nausea, abdominal pain, bloating, fever, and dizziness—were reported in the RCTs and case series reports.17,18 Possible procedure-related harms (including microperforation with colonoscopy19 and gastrointestinal bleeding,20 peritonitis,21 and pneumonia21 with use of the upper gastrointestinal tract route) were rarely reported. Mortality was not specifically reported as an outcome.3

There are several limitations to this systematic review. First, Drekonja et al3 classified patients into recurrent, refractory, or initial C. difficile infection. However, after reviewing the primary studies, it is unclear how classifications were defined within those studies, and importantly how recurrent and refractory infections were distinguished. Second, most studies reported a primary outcome that combined the resolution of symptoms and recurrence of infection, such as “cure without relapse” or “resolution of diarrhea without recurrence.” This combined outcome makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of the treatment. Future studies of fecal microbiota therapy should carefully consider using discrete outcomes of symptom resolution and recurrence prevention to evaluate the effectiveness of this treatment. Third, the optimal source of donor feces, amount and processing method of donor stool, and timing of the procedure relative to antimicrobial use were unclear.

Randomized Controlled Trials

One new RCT was published after the systematic review by Drekonja et al.3 Cammarota et al10 studied the effect of fecal microbiota therapy via colonoscopy in patients with recurrent C. difficile infection compared with the standard vancomycin regimen. Details about the RCT by Cammarota et al10 are outlined in Table A6 (Appendix 3). To assess the results of all three RCTs together, the previously published RCTs that were included in the systematic review by Drekonja et al are also summarized in Table A6.

The open-label RCT by Cammarota et al10 (N = 39 patients) has inclusion criteria (recurrent C. difficile infection), comparison groups (fresh fecal microbiota therapy vs. vancomycin), and a primary end point (resolution of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection without relapse after 10 weeks) similar to those of the previously published open-label RCT by Van Nood et al (N = 29 patients).17 Both RCTs reported a priori cases involving patients who developed recurrent C. difficile infection after the first donor feces infusion and were given a second infusion of feces.10,17 For patients in the infusion groups who required a second infusion of donor feces, follow-up was extended to 10 weeks after the second infusion.10,17 The main difference between the studies was the route of administration; the RCT by Cammarota et al10 used colonoscopy and the RCT by Van Nood et al17 used a nasogastric tube.

The open-label RCT by Youngster et al18 compared nasogastric tube versus colonoscopic delivery of previously frozen fecal microbiota in patients with recurrent and refractory C. difficile infection.

Resolution of Clostridium difficile Infection

In the study by Cammarota et al,10 fecal microbiota therapy via colonoscopy achieved significantly higher resolution rates of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection than vancomycin treatment alone (18/20 [90%] vs. 5/19 [26%], P < .0001).

Initially, 13 of 20 (65%) patients were cured after their first fecal microbiota infusion.10 The seven remaining patients were also diagnosed with pseudomembranous colitis. Six of these patients received multiple infusions (four received two infusions, one patient received three infusions, and one underwent four infusions), and one patient received one infusion.10

Five of the seven patients with pseudomembranous colitis were cured of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection; two patients still had symptoms and received one or two fecal microbiota infusions but died of C. difficile–related complications.10 All five of the seven patients with pseudomembranous colitis received a fecal microbiota infusion every 3 days until the colitis resolved.10

In the vancomycin group, 5 of 19 (26%) patients were cured of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection.10 In two cases that were refractory to antibiotic treatment, patients died of C. difficile–related complications. Twelve patients had a recurrence of C. difficile. Median time to recurrence was 10 days (range 4–21 days). At the time of recurrence, these patients had been discharged home, and the authors were not able to offer them fecal infusion.10

Cammarota et al10 noted that no patient refused the proposed treatment or expressed concerns about any aspect of fecal microbiota therapy.

Van Nood et al17 reported that, in 13 of 16 (81%) patients receiving fecal microbiota therapy, C. difficile–associated diarrhea resolved after the first infusion. When the three remaining patients received a second infusion, two of the three achieved resolution of symptoms. In the group receiving vancomycin alone, symptoms of C. difficile resolved in 4 of the 13 (31%) patients. Clostridium difficile symptoms resolved in 3 of the 13 (23%) patients receiving vancomycin and lavage (P < .001 in overall cure rates for both comparisons with the group receiving fecal microbiota therapy).17

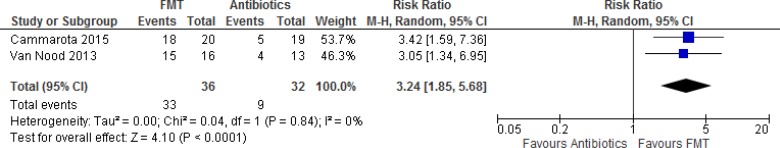

With inclusion criteria, comparison groups, follow-up duration, and primary end points similar to those in the RCTs by Cammarota et al10 and Van Nood et al,17 a meta-analysis was conducted to determine overall resolution of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection between patients who received fecal microbiota versus vancomycin (Figure 2). In the study by Van Nood et al,17 the group receiving vancomycin alone was used as the control group for the meta-analysis. Fecal microbiota therapy significantly improved overall resolution of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection in patients with recurrent C. difficile infection compared with treatment with vancomycin (summary risk ratio 3.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.85–5.68). Patients who received fecal microbiota therapy were three times as likely as patients receiving antibiotics to have their diarrhea symptoms successfully treated. The GRADE quality of evidence is moderate.

Figure 2: Meta-analysis of Overall Resolution of Diarrhea Associated With CDI in Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing FMT With Vancomycin.

Abbreviations: CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel test.

Youngster et al18 reported symptoms resolved in 8 of 10 patients in the colonoscopy group and in 6 of 10 patients in the nasogastric group (P = .628). One patient in the nasogastric group refused subsequent retreatment. The remaining five patients were given a second fecal microbiota infusion at a mean of 4.9 days (standard deviation 2.1 days) after first fecal microbiota treatment.18 All five patients requested fecal microbiota be delivered via the nasogastric route. Subsequently, four of the five patients were cured of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection. Overall, 8 of 10 (80%) patients in the nasogastric group and 10 of 10 (100%) patients in the colonoscopy group were cured of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection (P = .53).18

Quality of Life

None of the RCTs reported outcomes for quality of life.

Youngster et al18 found that the self-reported heath rating using a 10-point standardized questionnaire (1 was lowest and 10 was “best recent health baseline”) increased over the study period from a median of 5 (interquartile range 3–6) and 4 (interquartile range 2–5) in the colonoscopy and nasogastric groups, respectively, the day before fecal microbiota therapy (P = .44) to 8 (interquartile range 7–10) and 7 (interquartile range 5–8), respectively, 8 weeks after infusion. No statistical test compared self-reported health rating before fecal microbiota therapy with that 8 weeks after fecal microbiota treatment for either route of administration. The colonoscopy group had higher health scores accounted for by a higher reported score the day before fecal microbiota therapy. The groups did not differ regarding absolute change in scores (P = .51).18

Mortality

In the RCT by Cammarota et al, the first two patients in the fecal microbiota therapy group had pseudomembranous colitis.10 The first patient had a recurrence of C. difficile infection and received a second fecal microbiota infusion. The patient underwent another recurrence of C. difficile infection and started vancomycin but died of sepsis after 1 week. The second patient with pseudomembranous colitis was affected by severe cardiopathy and had a recurrence of C. difficile infection. Given the patient's deterioration, the authors could not offer a second fecal microbiota infusion. The patient received vancomycin but died 15 days later.10

In the vancomycin group, 2 of the 19 patients did not benefit from antibiotic treatment and died of C. difficile–related complications.10

In the RCT by Van Nood et al,17 the death of one patient from severe heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the vancomycin-only group was considered to be unrelated to the study drug. No patients died in the fecal microbiota therapy group.17

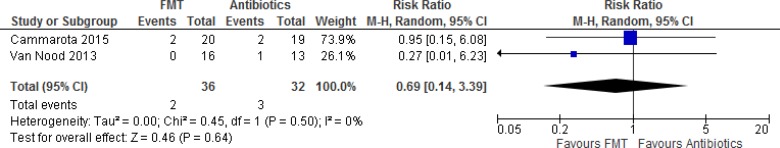

A meta-analysis was conducted to determine mortality in patients who received fecal microbiota compared with vancomycin therapy for the treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection (Figure 3). Overall, there was no significant difference in mortality between patients who received fecal microbiota therapy and those who received vancomycin (summary risk ratio 0.69, 95% CI 0.14–3.39). The GRADE quality of evidence was low.

Figure 3: Meta-analysis of Mortality in Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Fecal Microbiota Therapy With Vancomycin.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel test.

In the RCT by Youngster et al,18 one patient died 12 weeks after the procedure while hospitalized secondary to acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, including bleb (air sac) rupture requiring intubation and a chest tube. Although she was treated for several weeks with parenteral broad-spectrum antimicrobials, her C. difficile infection did not recur. Another patient died of metastatic laryngeal cancer 21 weeks after the procedure. A third patient was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.18 A fourth patient, treated by the upper gastrointestinal route, was hospitalized for Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis or gangrene usually affecting the perineum).18

Adverse Events

In the study by Cammarota et al,10 19 of 20 patients who received fecal microbiota therapy (95%) had diarrhea immediately after fecal infusion and 12 of 20 (60%) patients had bloating and abdominal cramping (symptoms resolved within 12 hours in all patients). No adverse events were reported in the vancomycin group.10

Van Nood et al17 reported that, immediately after fecal microbiota therapy, 15 of 16 patients had diarrhea (94%). Cramping in 5 of 16 (31%) patients and belching in 3 of 16 (19%) patients were also reported. In all patients, these symptoms resolved within 3 hours. No other adverse events related to study treatment were reported. No adverse events were reported in the vancomycin group.

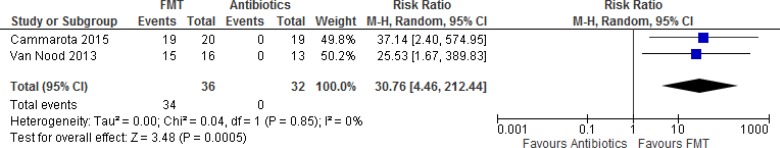

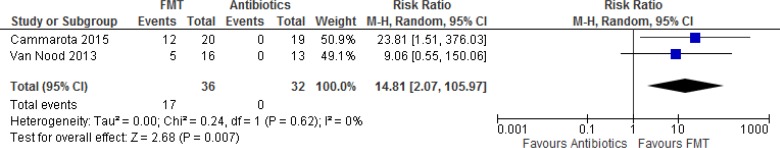

A meta-analysis was conducted to assess adverse events in patients who received fecal microbiota therapy compared with vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection (Figure 3). Overall, there were significant differences in treatment-related diarrhea and abdominal cramps between patients who received fecal microbiota therapy compared with vancomycin (summary risk ratios 30.76, 95% CI 4.46–212.44, and 14.81, 95% CI 2.07–105.97, respectively) (Figures 4 and 5). Patients treated with fecal microbiota therapy were 30 times more likely to have treatment-related diarrhea and abdominal cramping than those receiving vancomycin. The GRADE quality of evidence was low.

Figure 4: Meta-analysis of Adverse Event of Treatment-Related Diarrhea in Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Fecal Microbiota Therapy With Vancomycin.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel test.

Figure 5: Meta-analysis of Adverse Event Abdominal Cramps in Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing Fecal Microbiota Therapy With Vancomycin.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel test.

Youngster et al18 reported that adverse events likely to be related to fecal microbiota therapy included mild abdominal discomfort and bloating in 4 of 20 patients (20%).

Limitations of and Comments About the Randomized Controlled Trials

The randomized controlled trials had several limitations.

In the study by Cammarota et al, pseudomembranous colitis was present in 35% of patients with recurrent C. difficile infection.10 According to the authors, patients with pseudomembranous colitis required multiple fecal microbiota infusions to be cured.10 Patients in the vancomycin group did not undergo colonoscopy, and it is unknown how many patients treated with vancomycin had pseudomembranous colitis.10

All RCTs had small sample sizes, and meta-analyses generally yielded large confidence intervals for the summary estimates. The power calculation in the RCT by Van Nood et al17 was based on the efficacy of vancomycin for a first recurrence of C. difficile infection. Most patients had several relapses before inclusion. Therefore, the efficacy of vancomycin was lower than expected, which could have contributed to the findings. Cammarota et al10 confirmed the low response rate of a vancomycin regimen in curing patients with recurrent C. difficile infection (26% vs. the 31% reported by van Nood et al). Before their inclusion in the study, most patients had had relapses after previous vancomycin-based treatments. This exposure most likely contributed to the poor results of the vancomycin regimen in both studies.

The RCT by Youngster et al18 was a small feasibility study and not powered to detect a difference between the nasogastric versus colonoscopic administration of fecal microbiota.

It is unclear what standardized questionnaire was used to assess self-reported health in the RCT by Youngster et al (no reference was provided).18

Observational Studies

Details of the six observational studies are summarized in Table A8.11–16 All studies were uncontrolled, retrospective case series with sample sizes ranging from 6 to 61 patients. Patients received fecal microbiota therapy because of recurrent C. difficile infection in all six studies.11–16 Three studies specifically reported patients as having recurrent and refractory C. difficile infection.13,15,16 In terms of route of administration of fecal microbiota therapy, four studies used colonoscopy,12,13,15,16 one study used orally administered capsules,11 and one study used nasogastric tubing.14

Resolution of Clostridium difficile Infection

Overall, resolution or cure rates of C. difficile–associated diarrhea ranged from 89% to 100%.11–16

For most patients in the case series, C. difficile infection–associated diarrhea resolved after the first fecal microbiota treatment was administered (range 55%–100%).11–16 The total number of times fecal microbiota were administered for complete resolution of C. difficile infection–associated diarrhea in the studies ranged from one to three.11–13,16

Quality of Life

Quality of life was not reported in any of the case series.

Mortality

Hirsch et al reported one death in the case series of 19 patients.11 This 84-year-old man had dementia, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, arthritis, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. He had recurrent symptoms consistent with C. difficile within 2 to 4 weeks of each of four fecal microbiota therapy attempts.11 He required hospitalization for diarrhea, dehydration, and acute kidney injury. The diarrhea resolved with oral vancomycin and rifaximin. He developed health care–acquired pneumonia, which was treated with systemic antimicrobial therapy. Oral vancomycin was continued. He did not develop recurrent diarrhea, but died of respiratory failure. His death was considered unrelated to the fecal microbiota therapy.11

Two case series did not report any deaths in patients who received fecal microbiota therapy.12,13

Satokari et al reported that a nonresponder in the group receiving fresh feces transplantation developed C. difficile infection after ciprofloxacin administration for urinary tract infection.15 She had atherosclerosis and was receiving long-term dialysis. Despite C. difficile treatment with antibiotics, the patient died of multiple medical problems 2 months after fecal microbiota treatment.15

During the year after fecal microbiota therapy, one patient in the fresh fecal microbiota therapy group died of unrelated illnesses.15 In the group receiving frozen fecal microbiota transplants, two patients had a relapse of C. difficile infection.15 In these cases, C. difficile infections were subsequently treated with antibiotics. Both patients died, one of arterial thrombosis in the lower limb and the other one of the C. difficile infection.15

Fischer et al reported three deaths associated with C. difficile infection: (1) death of sepsis within 24 hours of the first fecal microbiota treatment; (2) death of a patient who failed to benefit from three courses of fecal microbiota therapy following colectomy 6 weeks after orthotopic liver transplantation; and (3) death of sepsis after being treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection 92 days following the first fecal microbiota treatment.16 Five patients died of causes unrelated to C. difficile infection.16

The overall cumulative survival after the first fecal microbiota treatment was 93% (95% CI 84–100) at 1 month and 76% (95% CI 62–93) at 3 months.16

Lagier et al reported global and 1-month mortality in elderly patients (mean age 84 years, range 66–101 years) who received fecal microbiota therapy.14 Patients were divided into two groups: antibiotics plus late fecal microbiota therapy (patients were treated with antibiotics; fecal microbiota therapy was used only in cases of a least three treatment failures or relapses) and antibiotics plus early fecal microbiota therapy (antibiotics and fecal microbiota therapy were offered early during the first week following diagnosis).14 Most patients in the late fecal microbiota therapy group received only antibiotics; three patients were also treated with fecal microbiota therapy.14

There was a significant difference in global mortality between the two patient groups: 3 of 16 (19%) who received early fecal microbiota therapy versus 29 of 45 (64%) who received late fecal microbiota therapy (P < .001).14 There was also a significant difference in 1-month mortality between the groups: 1 of 16 (6%) who received early fecal microbiota therapy versus 24 of 43 (56%) who received late fecal microbiota therapy (P < .0003).14

Of the 40 patients treated only by antibiotics in the group receiving late fecal microbiota therapy, 23 died before 1 month (58%).14 Among these 23 patients, 17 patients (74%) died during the first week following diagnosis. Among the three patients treated by antibiotics and late fecal microbiota therapy, 1-month mortality was one of three (33%).14

Lagier et al14 reported that antibiotics and early fecal microbiota therapy was associated with a significant decrease in mortality compared with antibiotics and late fecal microbiota therapy (log-rank test P < .001).

Adverse Events

Adverse events reported in the studies included abdominal pain that was reported in 5 of 19 patients from Hirsch et al (mild and transient in four patients and moderate to severe in one patient who also had irritable bowel syndrome, but pain subsided 3 days after fecal microbiota treatment).11

Ray et al12 reported adverse events in 5 of 20 patients during an 8-month follow-up:

One had pain or nausea after colonoscopy

One continued to have diarrhea (but results for C. difficile remained negative during 8 months of follow-up)

One had bloating or cramps daily “consistent with her pre-existent inflammatory bowel disease symptoms. The patient stated that the symptoms did not worsen after the procedure”

One had flatulence and nausea for a few weeks after fecal microbiota therapy but noted an improvement in the symptoms of diarrhea

One reported, more than a month later, that she suffered a cerebrovascular accident at another hospital and had complications, including persistent nausea and vomiting with abdominal pain” after eating that eventually resolved

Lagier et al14 reported that, of 33 elderly patients treated with fecal microbiota procedures (including those treated with successive fecal microbiota treatments), 24 patients (73%) had treatment-related diarrhea that resolved on the next day. For adverse events, Lagier et al also reported that one patient refused the nasogastric tube on the day of transplantation, one patient had uncontrollable nausea caused by the nasogastric tube, and one patient presented with acute heart failure.

Limitations of and Comments About the Observational Studies

The observational studies had limitations.

All studies were retrospective case series. Primary outcomes were reported as a combination of resolution of symptoms and prevention of recurrence.11–16

The use of antibiotics for treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection around the time of fecal microbiota administration varied across studies. Some studies11,13,15,16 discontinued antibiotics 24 to 48 hours before fecal microbiota treatment. Several studies resumed antibiotic and repeat fecal microbiota therapy if patients experienced recurring C. difficile symptoms.11,16 Ray et al12 stated that all patients received antibiotic treatment (vancomycin, metronidazole, or fidaxomicin) for C. difficile infection before fecal microbiota treatment; however, it is unclear whether patients continued antibiotic therapy during and after fecal microbiota therapy. Lagier et al14 reported outcomes of patients who received antibiotics (vancomycin, metronidazole, or fidaxomicin) and fecal microbiota therapy simultaneously.

Discussion

Beyond the six patients in the case series identified by Drekonja et al,3 no additional studies of patients treated with fecal microbiota for initial C. difficile infection were identified in the updated literature search. All studies in this systematic review included patients with recurrent C. difficile infection. However, a few studies explicitly stated that patients were included if they had recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection.13,15,16 International guidelines (Appendix 5) on the use of fecal microbiota therapy all specifically refer to patients with recurrent C. difficile infections.1,22–24 Health Canada currently provides a provisional interpretation that allows fecal microbiota to be used to treat patients with recurrent C. difficile infection unresponsive to conventional therapies.4

Overall, results of observational studies were generally consistent with results from RCTs. The resolution of diarrhea associated with recurrent C. difficile infection was the primary outcome for all studies. Adverse events associated with fecal microbiota therapy were generally minimal and short term (diarrhea, abdominal cramping). Quality of life was not reported as an outcome in any of the studies in this systematic review.

The route of administration for fecal microbiota varied across studies. The only study included in this systematic review that compared different routes of administration was a small RCT.18 Youngster et al found no significant difference in resolution rates for administration of fecal microbiota therapy via nasogastric tube versus colonoscopy; however, the RCT was considered a feasibility study and not statistically powered to detect a difference between the two routes of administration.18

An expert consultant stated that anecdotal evidence increasingly indicates that multiple administrations are required for most cases of recurrent C. difficile infection to fully resolve (Dr. Susy Hota, written communication, October 19, 2015). The frequency and timing of repeat fecal microbiota treatment is unclear and could need to be tailored to individual cases (Dr. Susy Hota, written communication, October 19, 2015). It is also unclear whether different donors should be used for repeat administration of fecal microbiota (in hopes of eventually getting the right “microbiome match”) (Dr. Susy Hota, written communication, October 19, 2015).

Conclusions

In patients with recurrent C. difficile infection:

Fecal microbiota therapy is effective in resolving diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection compared with antibiotics (GRADE: moderate)

There is insufficient evidence to conclude that fecal microbiota therapy reduces mortality compared with antibiotics (GRADE: low)

Fecal microbiota therapy is associated with a significant increase in adverse events, specifically treatment-related diarrhea and abdominal cramping compared with antibiotics (GRADE: low). In the studies, these adverse events were short lived and resolved successfully

ECONOMIC EVIDENCE REVIEW

Objectives

This economic section of the health technology assessment reviewed the literature for the cost-effectiveness of fecal microbiota therapy compared with antibiotic treatment in adults with recurrent C. difficile infection.

Methods

Sources

We performed an economic literature search on August 4, 2015, using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Health Technology Assessment Database, and National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database, for studies published from January 1, 2000, to August 4, 2015. We also extracted economic evaluation reports developed by health technology assessment agencies by searching the websites of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Institute of Health Economics, Institut national d'excellence en sante et en services, McGill University Health Centre Health Technology Assessment Unit, and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) Registry (available at https://research.tufts-nemc.org/cear4). Finally, we reviewed reference lists of included economic literature for any additional relevant studies not identified through the systematic search.

Literature Screening

We based our search terms on those used in the clinical evidence review of this health technology assessment and applied economic filters to the search results. Study eligibility criteria for the literature search are listed below. A single reviewer reviewed titles and abstracts and, for those studies meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we obtained full-text articles.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published between January 1, 2000, and August 4, 2015

Studies in adults who had initial, recurrent or refractory C. difficile infection

Studies of fecal microbiota therapy (via variable routes of administration and variable timing and frequency) for C. difficile infection and recurrent C. difficile infection

Studies where the comparators were standard antibiotic treatment

Exclusion Criteria

Animal and in vitro studies

Editorials, case reports, or commentaries

Studies of fecal microbiota therapy for indications other than C. difficile infection or recurrent C. difficile infection

Outcomes of Interest

Full economic evaluations: cost-utility analyses, cost-effectiveness analyses, cost-benefit analyses

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on the following:

Source (i.e., name, location, year)

Study design (perspective, time horizon) and population

Indications, interventions, and comparators

Results: outcomes (i.e., health outcomes, costs, and cost-effectiveness)

Limitations

The review was conducted by a single reviewer, and the search was limited to 15 years.

Results

Literature Search

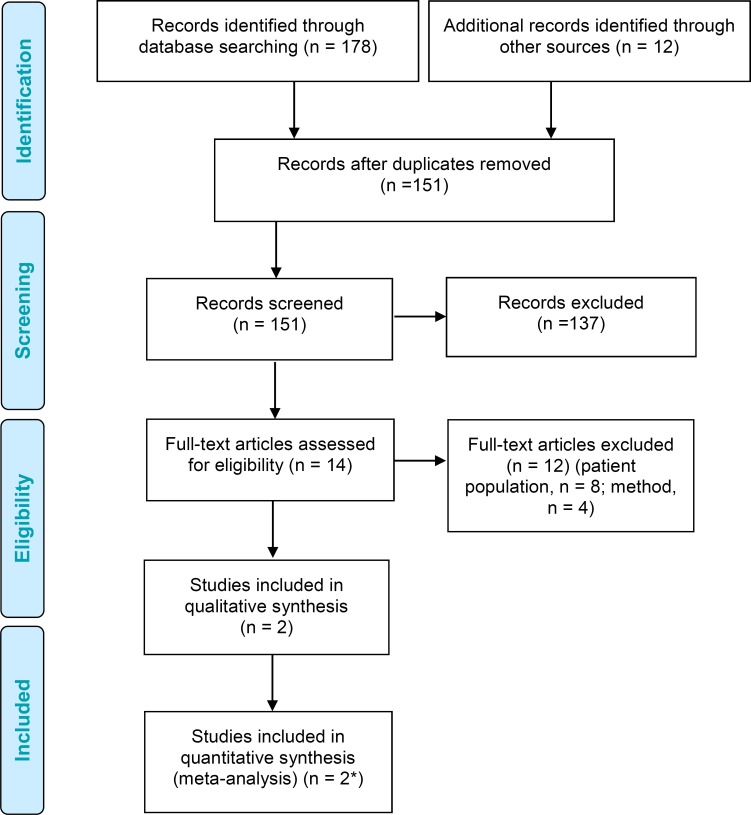

The database search yielded 151 citations published between January 1, 2000, and August 4, 2015 (with duplicates removed). A longer (15-year) time horizon was used in the literature search to ensure that all relevant economic evaluations were captured based on the scoping phase. We excluded a total of 137 articles from information in the title, abstract, and full text. We then examined the full texts of 14 potentially relevant articles for further assessment. Figure 6 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) adapted for this economic review.

Figure 6: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Flow Diagram.

*Incorporates same studies included in qualitative synthesis.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.9

Two studies met the inclusion criteria. We hand-searched the reference lists of the included studies and health technology assessment websites to identify other relevant studies, and no additional citations were included.

Critical Review

The two economic evaluations meeting the inclusion criteria are summarized and appraised in Table 1.

Table 1:

Results of Economic Literature Review for Fecal Microbial Therapy—Summary

| Name, Year, Location | Study Design, Time Horizon, and Perspective | Population and Indication | Interventions and Comparators | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes QALYs, Cure Rates | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | ||||

| Varier et al, 201525 United States |

Design Decision-analytic model Time horizon 90 days Perspective Third-party payer |

Population RCDI patients Indication FMT for first-line treatment of RCDI patients |

Interventions FMT colonoscopy Comparator Vancomycin |

FMT 0.242 83%–100% Vancomycin 0.235 59%–75% |

FMT $1,669 vs. vancomycin $3,788 Discount No discounting necessary because simulated patients in model were followed for 90 days |

Dominant |

| Konijeti et al, 201426 United States |

Design Decision-analytic model comparing 4 treatment strategies for first-line treatment of RCDI Time horizon 1 year Perspective Societal |

Population RCDI patients Indication FMT for first-line treatment of RCDI in hypothetical cohort |

Interventions FMT colonoscopy Comparators Metronidazole, vancomycin, fidaxomicin |

FMT 0.8719, 94.5% Vancomycin 0.8580, 91.6% Metronidazole 0.8292, 71% Fidaxomicin 0.8653, 93.7% |

Cost FMT $3,149 Vancomycin $2,912 Metronidazole $3,941 Fidaxomicin $4,261 Discount No discounting necessary because simulated patients in model were followed for 1 year |

FMT compared with vancomycin: ICER $17,016 per QALY FMT vs. metronidazole Dominant FMT vs. fidaxomicin Dominant |

Abbreviations: FMT, fecal microbiota transplant; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RCDI, recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

Methodologic Quality of Included Studies

The two studies were directly applicable or partially applicable to the research question and were deemed relevant to the eligible patient population.

Discussion

Varier et al25 constructed a decision-analytic model using inputs from the published literature to compare standard vancomycin treatment with fecal microbiota therapy for recurrent C. difficile infection. This analysis was completed from a third-party payer perspective. The effectiveness measure was quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Fecal microbiota therapy was less costly ($1,669 vs. $3,788 USD) and more effective (0.242 vs. 0.235 QALYs) than vancomycin for recurrent C. difficile infection (Table 1). Sensitivity analyses showed that fecal microbiota therapy was the dominant treatment strategy if the cure rate for fecal microbiota therapy was higher than 70% and for vancomycin was higher than 91%, and if the cost of fecal microbiota therapy was lower than $3,206 USD. The results of this study suggest that using fecal microbiota therapy to manage recurrent C. difficile infection can save money and help reduce the economic burden on the health care system.25

Konijeti et al26 demonstrated that fecal microbiota therapy via colonoscopy is a cost-effective strategy for recurrent C. difficile infection, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $17,016 USD per QALY (Table 1) compared with antibiotic treatment (vancomycin). Fecal microbiota therapy was also dominant—less costly and more effective—than metronidazole and fidaxomicin for recurrent C. difficile infection. The decision model constructed for this analysis suggested that treatment with fecal microbiota via colonoscopy would have cure rates of 88% or higher and recurrence rates of less than 15%; this is consistent with findings from the study performed by Brandt et al,27 which reported fecal microbiota therapy cure rates to be greater than 90%. Considering the costs and training required to perform fecal microbiota transplant, the analysis strongly suggested a need for standardized routes of administration for fecal microbiota if the treatment is to be used frequently for recurrent C. difficile infection.

After reviewing these two studies and the existing clinical studies, we decided against developing a full economic model. The data would have been similar to the data in these two evaluated economic studies, and the evidence presented about the cost-effectiveness of fecal microbiota therapy in these studies was sufficient for the Ontario context.

Conclusions

One of the two economic evaluations concluded that fecal microbiota therapy can save money compared with standard (vancomycin) treatment. The study showed that fecal microbiota therapy is dominant (less expensive, more effective) over metronidazole and fidaxomicin because of the higher observed cure rates.25 The second economic evaluation concluded fecal microbiota therapy is a cost-effective strategy for managing recurrent C. difficile infection.26

BUDGET IMPACT ANALYSIS

We conducted a budget impact analysis from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care to determine the estimated cost burden of C. difficile infection for 1 year (2015) and the potential costs of fecal microbiota therapy for recurrent C. difficile infection over the next 3 years. All costs are reported in 2015 Canadian dollars. Clostridium difficile infection includes both initial and recurrent infections, and recurrent C. difficile infection refers to one or more episodes after an initial infection with C. difficile.

Objectives

Our objectives were to estimate:

The 1-year cost to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care of C. difficile infections and the corresponding 1-year cost of treating these infections with fecal microbiota therapy

The potential costs to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care over the next 3 years of using fecal microbiota therapy for recurrent C. difficile infection among eligible patients

Methods

Target Population

We created a budget impact model to address the 1-year (2015) impact of C. difficile infection on the Ontario health care system using the reported volume of episodes multiplied by the cost of treatment to patients. The total number of C. difficile cases (both initial and recurrent) was reported to be 5,810 in 2014/2015; this was used as the prevalent year. Data were obtained by Health Quality Ontario from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (Health Analytics Branch, written communication, October 27, 2015).

Next, we determined the potential impact to the ministry of fecal microbiota therapy for recurrent C. difficile infections currently treated with standard antibiotics (vancomycin and metronidazole). It is estimated that recurrent C. difficile infections account for 27% of total C. difficile cases.28 The impact of fecal microbiota therapy on the ministry's budget was calculated for a fixed number of procedures on the basis of expert opinion.

Canadian Costs

Cost parameters were calculated from several sources (Tables 2 and A10):

Table 2:

Average Cost Associated With CDI and RCDI Treatment per Episode

| Cost Parameter | Cost, $ | Source/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Community-Based Treatment | ||

| FMT colonoscopy | 1,429 | Varier et al, 2015,25 Biltaji et al, 2014, and Guo et al, 201132 |

| Total cost per patient with CDI | 542 | Assumed that all patients receive vancomycin |

| Total cost per RCDI episode | 574 | Assumed that all patients receive vancomycin |

| Average cost per FMT treatment of RCDI | 1,866 | Calculated from Levy et al, 2015,28 Varier et al, 2015,25 Biltaji et al, 2014,33 and Guo et al, 201132 |

| Hospital-Based Treatment | ||

| Total cost per patient with RCDI | 16,096 | Calculated from Levy et al, 2015,28 Varier et al, 2015,25 Biltaji et al, 2014,33 and Guo et al, 201132 |

| Cost per RCDI FMT treatment | 9,422 | Calculated from Levy et al, 2015,28 Varier et al, 2015,25 Biltaji et al, 2014,33 and Guo et al, 201132 |

Abbreviations: CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; RCDI, recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

Analysis

The 1-year (2015) cost impact of the 5,810 episodes (2014/2015) of C. difficile infection (initial and recurrent) on the Ontario care system was calculated. This cost included both hospital- and community-based treatments in Ontario. It is estimated that 53% of total C. difficile infections receive hospital-based treatment and 47% receive community-based treatment.28 The 1-year cost impact was calculated from the product of the number of C. difficile infection episodes (initial and recurrent), the percentage of cases per treatment location (hospital versus community), and the cost associated with both the place and type of infection (initial versus recurrent).

The base case for fecal microbiota treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection was calculated based on an expert estimate of about 500 to 1,000 procedures being performed per year in Ontario (C. Lee, written communication, October 27, 2015). The analysis assumed that 500 fecal microbiota procedures will be performed in year 1 of introduction, with a 50% annual increase, reaching a maximum of 1,000 fecal microbiota procedures in year 3 (Table 4). Patients with recurrent C. difficile infection are usually treated with standard antibiotics (vancomycin and metronidazole) in the hospital or community.28 For community-based treatment, we assumed that all patients are treated with a standard regimen of 10 to 14 days of vancomycin. All antibiotic treatments were assumed to be publicly funded. The budget impact was calculated from the difference in the total cost of treating recurrent C. difficile infection with standard antibiotic therapy and the total cost of treating these patients with fecal microbiota therapy in hospitals and communities.

Table 4:

Three-Year Budget Impact of FMT for RCDI in Ontario

| Year | Number of Patients Receiving FMT | Estimated Total Cost, $ in Millionsa |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 500 | −1.5 |

| 2 | 750 | −2.2 |

| 3 | 1,000 | −2.9 |

| Total | 2,250 |

Abbreviations: CB, community based; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; HB, hospital based; RCDI, recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

[(RCDITotal × 53%) × Cost FMThb] + [(RCDIcb × 47%) × Cost FMTcb].

Sensitivity analyses were performed on two key parameters in the budget impact model: the proportion of infections treated in the hospital (70%) versus the community (30%). This proportion was based on that in the published literature.28 The cost of fecal microbiota procedures was discounted by 25%. In Ontario, the fecal transplant is generally administered via enema, which is less costly than colonoscopy (C. Lee, oral communication, August 5, 2015); colonoscopy accounts for about 25% (20%–30%) of the fecal microbiota therapy costs.

Results

Base Case

In 2014/2015, our model suggested that C. difficile infection in Ontario was associated with costs of about $47.8 million dollars. If all cases of recurrent C. difficile infection had been eligible for and treated with fecal microbiota therapy, there would have been a potential reduction of about $5.2 million in the overall treatment cost (Table 3).

Table 3:

Cost to Ontario of CDI Antibiotic Treatment in 2014/2015 and Potential Total Yearly Cost of FMT

| Treatment Subgroups | Target Population | Estimated Total Cost, $ in Millions |

|---|---|---|

| Current standard treatment (antibiotics) in Ontario (HB + CB) | 5,810a | 47.8c |

| Standard treatment (antibiotics) for recurrent CDIs (HB + CB) in patients eligible for FMT | 1,575b | 13.9d |

| FMT treatment (HB + CB) for recurrent CDIs in eligible patients | 1,575 | 8.7e |

| Net budget impact of FMT for recurrent CDIs | –5.2f |

Abbreviations: CB, community based; CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; HB, hospital based; RCDI, recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

Total C. difficile infections (initial and recurrent) in 2014/2015: Health Analytics Branch, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Recurrent C. difficile infections (27.1% of 5,810).

[(CDITotal × 53%) × Cost CDIhb] + [(CDITotal × 47%) × Cost CDIcb] + [(RCDITotal × 53%) × Cost RCDIhb] + [(RCDIcb × 47%) × Cost RCDIcb].

[(RCDITotal × 53%) × Cost RCDIhb] + [(RCDIcb × 47%) × Cost RCDIcb].

[(RCDITotal × 53%) × Cost FMThb] + [(RCDIcb × 47%) × Cost FMTcb].

Difference between e and d.

Over the next 3 years, an estimated total of 2,250 (Σ Year 1+Year 2+ Year 3) fecal microbiota procedures could be performed in Ontario for recurrent C. difficile infection. If fecal microbiota therapy were adopted in Ontario to treat recurrent C. difficile infection, and considering it from the perspective of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care as the payer, an estimated $1.5 million would be saved after the first year of adoption and $2.9 million after 3 years (Table 4).

Sensitivity Analysis

The budget impact is sensitive to the proportion of patients treated in the hospital (Table 5) and the cost of fecal microbiota therapy (Table 6). Whether we increase the proportion of patients treated in the hospital to 70% or decreased the cost of fecal microbiota treatment by 25%, the impact to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is potentially net savings (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5:

Three-Year Budget Impact of FMT for RCDI in Ontario: Number of Patients Treated in Hospital Increased to 70%

| Year | Number of Patients Receiving FMT | Estimated Total Cost, $ in Millionsa |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 500 | −2.1 |

| 2 | 750 | −3.2 |

| 3 | 1,000 | −4.3 |

| Total | 2,250 |

Abbreviations: CB, community based; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; HB, hospital based; RCDI, recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

[(RCDlTotal × 70%) × Cost FMThb] + [(RCDIcb × 30%) × Cost FMTcb].

Table 6:

Three-Year Budget Impact of FMT for RCDI: Cost of FMT Decreased by 25%

| Year | Number of Patients Receiving FMT | Estimated Total Cost, $ in Millionsa |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 500 | −1.6 |

| 2 | 750 | −2.5 |

| 3 | 1,000 | −3.3 |

| Total | 2,250 |

Abbreviations: CB, community based; FMT, fecal microbiota therapy; HB, hospital based; RCDI, recurrent Clostridium difficile infection.

[(RCDlTotal × 53%) × 75% × Cost FMThb] + [(RCDIcb × 47%) × 75% × Cost FMTcb].

Limitations

The number of C. difficile infections in Ontario is based on 2014/2015 numbers and includes both the initial and recurrent cases. This might underestimate costs as some experts believe symptoms might resolve in some patients before an actual diagnosis of C. difficile infection is made.

Presently the distribution of recurrent C. difficile infections treated in hospital versus the community is difficult to estimate because there is no consistency in reporting.28 Hence, we assumed that treatment of recurrent C. difficile infections has the same distribution as treatment of initial C. difficile infections: 53% in hospital and 47% in the community.

We assumed that all patients treated in the community received a standard regimen of 10 to 14 days of vancomycin, and we included this as a cost to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. This assumption may present an overestimation of the cost associated with these cases.

The Ontario cost for vancomycin was not available at the time of this writing, so we used the published price from Quebec. The cost in Ontario and Quebec is assumed to be equivalent because the prices for patented medicines, like vancomycin, are regulated by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Therefore, the use of Quebec costs may not significantly impact the results.

The number of fecal microbiota procedures is based on expert opinion (C. Lee, written communication, October 27, 2015).

Discussion and Conclusions

Based on our analysis, C. difficile infection (both initial and recurrent episodes) in Ontario was estimated to cost $48 million in 2014/2015. We found that most of Ontario's cost (96%) is attributed to hospital-based treatment (53%) of the total initial and recurrent C. difficile episodes. Recurrent C. difficile infections account for almost half (49.4%) of the cost of treating this disease.

Some hospital centres in Ontario have championed fecal microbiota therapy for recurrent C. difficile infection. Although the number of fecal microbiota procedures performed per year is still unknown, experts estimate that 500 to 1,000 fecal microbiota transplantation procedures can be performed every year. Our analysis predicts a cost savings over the next 3 years if fecal microbiota therapy is used instead of standard antibiotic therapy to treat recurrent C. difficile infection. We increased the number of fecal microbiota procedures performed in the hospital and also decreased the price of the fecal microbiota procedure; both scenarios found cost savings if fecal microbiota therapy becomes the standard treatment for recurrent C. difficile infection.

PUBLIC AND PATIENT ENGAGEMENT ANALYSIS

Background

The primary aim of public and patient engagement in the context of health technology assessment is to “ensure that assessments and decisions are informed by the unique perspectives of those with the lived experience of a health condition and its management.”34

Patient and caregiver input can serve as a unique source of evidence about the personal impact of a disease or condition and how technology can make a difference in people's lives. It can also identify gaps or limitations in the published research (e.g., outcome measures that do not reflect what is important to patients and caregivers).35–37 Patient, caregiver, and public input can provide additional information or perspectives on the more general ethical and social-values implications of technology and treatments.

Dealing with C. difficile infection is perceived as directly affecting patients’ quality of life. To understand how fecal microbiota therapy might affect an individual's quality of life, we spoke directly with physicians who had a close relationship with the patients under their care and their families and caregivers. Our preferred approach is to speak directly with patients themselves; however, resource limitations precluded this level of engagement for this health technology assessment. Understanding and appreciating day-to-day functioning in this population helps to place the potential value of the intervention into context.

Methods

Activity and Rationale

The engagement typology we selected for this health technology assessment was a consultation.38 Consultation refers to the process of gathering information (e.g., social values, experiential input) from the public, patients, and caregivers.39

We chose to examine lived experience through physicians’ perceptions because of resourcing and staffing considerations. Having two physicians with close proximity and familiarity with the relevant patient population provided rationale for soliciting their perceptions of patients’ lived experience in this project.

Recruitment

We relied on two physicians who were clinical experts caring for individuals and families with personal experience of the infection.

Interview Questions

For the purposes of this assessment, a member of the Patient, Caregiver, and Public Engagement office at Health Quality Ontario surveyed physicians about their perceptions of their patients through a series of open-ended questions. Questions for the interview were based on a list developed by the Health Technology Assessment international Interest Group on Patient and Citizen Involvement in Health Technology Assessment to elicit responses specific to how health technology affects lived experience and quality of life.40

Survey questions focused on how C. difficile infection affects quality of life and on patients’ experiences with other health interventions, including other ongoing treatments, that are intended to manage the condition. The questions focused on patient experiences with the fecal microbiota procedure itself, any follow-up required, and any perceived benefits or limitations of the intervention. The survey is attached as Appendix 6.

Analysis

We selected a modified version of a grounded-theory method to analyze information from the surveys by coding responses and comparing themes.41,42 This approach allowed us to identify and interpret patterns in the survey data about the meaning and implications of the condition and intervention for participants’ quality of life.43

Results

Clostridium difficile and Quality of Life

Physicians perceived that all patients with C. difficile infection have lower quality of life regardless of whether the infection is a first episode or recurrent. This reduced quality of life is exacerbated if diagnosis is delayed. Examples of how C. difficile infection affects quality of life include preventing patients and their families from going to work, travelling, hosting social gatherings, and seeing other family and grandchildren.

Most patients with C. difficile infection do not leave their house during an acute episode as they experience extreme urgency and incontinence with diarrhea. Many feel socially isolated and are concerned about becoming a burden on their families. Some patients require emergency or ambulatory care, and some require hospitalization.

Many patients with recurrent C. difficile infection report feeling as though they are walking on eggshells between episodes and being extremely anxious about recurrence. They are also very concerned about transmitting the infection to loved ones.

Experiences With Other Medical Treatment

Physicians reported that most patients have little success with two antibiotic medications: metronidazole and fidaxomicin. Physicians said that many patients reported feeling better with vancomycin and indicated that this medication acts within a few days and ensures a good quality of life.

Fecal Microbiota Therapy

Generally speaking, physicians perceived that patients were happy with the processes needed to receive fecal microbiota therapy. The most cumbersome part of the experience was described as aligning the timing of donor screening with the appropriate time for intervention. A few patients reported some reservations because of an “ick” factor, relating to general unsureness about receiving feces from another person, although most were receptive to the procedure itself. Physicians reported few patients experienced discomfort during the procedure, aside from a very mild temporary cramping during the infusion.

Impact on Quality of Life

Physicians perceived that, within 2 weeks of fecal microbiota treatment, most patients were able to resume daily activities. Some patients reported a little trepidation about embarking on longer-term activities, such as travel or longer periods away from home. Some patients required multiple fecal microbiota treatments or antibiotic follow-up therapy, but for many, no follow-up therapies were required.

Discussion

Several important themes emerged from physician surveys about their perceptions of their patients and families.

One of the most important themes described by physicians was how greatly C. difficile infection influences day-to-day functioning of patients, especially for any activity that involves being away from their own homes. These activities include integral activities (such as going to work), other important daily life activities (like hosting family and friends), and even simple tasks requiring patients to leave their house (such as running errands and going to appointments). The social isolation felt by patients with recurrent C. difficile infection can be overwhelming.

While some success was described after using standard therapies, the two physicians surveyed believed that the fecal microbiota procedure seemed to restore quality of life for patients with recurrent C. difficile infection. The procedure itself did not come across as difficult or onerous to patients, with an overall perceived benefit of patients and their families being able to return to normal activities of daily living.

Conclusion

The two physicians surveyed reported that recurrent C. difficile infection seemed to significantly reduce their patients’ quality of life. The fecal microbiota procedure seemed to improve their patients’ quality of life, which speaks to the value of this intervention from the lived experience.

Acknowledgments

the medical editor was Elizabeth Jean Betsch. Others involved in the development and production of this report were Irfan Dhalla, Nancy Sikich, Andrêe Mitchell, Kellee Kaulback, Anne Sleeman, Claude Soulodre, Kristan Chamberlain, Susan Harrison, and Jessica Verhey.

We are grateful to Drs. Susy Hota and Christine Lee for their expert consultations.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMSTAR

Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews

- CI

Confidence interval

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

- PICO

Population, intervention, comparison, outcome

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- QALY

Quality-adjusted life-year

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Clinical Literature Search

Search date: July 30, 2015

Databases searched: All Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, CRD Health Technology Assessment Database, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and NHS Economic Evaluation Database

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <June 2015>, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews <2005 to June 2015>, EBM Reviews - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects <2nd Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - Health Technology Assessment <2nd Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - NHS Economic Evaluation Database <2nd Quarter 2015>, Embase <1980 to 2015 Week 30>, All Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>

Search Strategy:

| 1 | Clostridium difficile/ (17125) |

| 2 | Enterocolitis, Pseudomembranous/ (11518) |

| 3 | Clostridium Infections/ (6438) |

| 4 | (clostridium difficile or c difficile or c diff or clostridium enterocolitis or ((pseudomembranous or antibiotic associated) adj2 (enteritis or colitis or enterocolitis)) or clostridium infection*).tw. (26393) |

| 5 | or/1–4 (37418) |

| 6 | exp Feces/ (125351) |

| 7 | Microbiota/ (12252) |

| 8 | (((fecal or faecal or feces or faeces or stool or stools or microbiota*) adj4 (transplant* or transfus* or transfer* or infusion* or donor* or donation* or therap* or suspension)) or FMT or bacteriotherap* or human probiotic infus* or intestinal microbiome restorat*).tw. (5960) |

| 9 | or/6–8 (141077) |

| 10 | Diarrhea/th [Therapy] (6332) |

| 11 | or/9–10 (147039) |

| 12 | 5 and 11 (4285) |

| 13 | exp Animals/ not (exp Animals/ and Humans/) (8226588) |

| 14 | 12 not 13 (3967) |

| 15 | limit 14 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,DARE; records were retained] (3475) |

| 16 | limit 15 to yr=“2013 -Current” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] (1098) |

| 17 | 16 use pmoz,cctr,coch,dare,clhta,cleed (524) |

| 18 | peptoclostridium difficile/ (773) |

| 19 | Clostridium difficile infection/ (6827) |

| 20 | Clostridium infection/ (6531) |

| 21 | pseudomembranous colitis/ (11692) |

| 22 | (clostridium difficile or c difficile or c diff or clostridium enterocolitis or ((pseudomembranous or antibiotic associated) adj2 (enteritis or colitis or enterocolitis)) or clostridium infection*).tw. (26393) |

| 23 | or/18–22 (37100) |

| 24 | feces/ (120531) |

| 25 | feces microflora/ (4066) |

| 26 | (((fecal or faecal or feces or faeces or stool or stools or microbiota*) adj4 (transplant* or transfus* or transfer* or infusion* or donor* or donation* or therap* or suspension)) or FMT or bacteriotherap* or human probiotic infus* or intestinal microbiome restorat*).tw. (5960) |

| 27 | or/24–26 (128618) |

| 28 | diarrhea/th [Therapy] (6332) |

| 29 | or/27–28 (134579) |

| 30 | 23 and 29 (4275) |

| 31 | (exp animal/ or nonhuman/) not exp human/ (9402331) |

| 32 | 30 not 31 (3929) |

| 33 | limit 32 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,DARE; records were retained] (3452) |

| 34 | limit 33 to yr=“2013 -Current” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] (1143) |

| 35 | 34 use emez (649) |

| 36 | 17 or 35 (1173) |

| 37 | 36 use pmoz (507) |

| 38 | 36 use emez (649) |

| 39 | 36 use cctr (8) |

| 40 | 36 use coch (0) |

| 41 | 36 use dare (3) |

| 42 | 36 use clhta (4) |

| 43 | 36 use cleed (2) |

| 44 | remove duplicates from 36 (829) |

Economic Literature Search

Search date: August 4, 2015

Databases searched: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Health Technology Assessment Database and National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <June 2015>, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews <2005 to June 2015>, EBM Reviews - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects <2nd Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - Health Technology Assessment <2nd Quarter 2015>, EBM Reviews - NHS Economic Evaluation Database <2nd Quarter 2015>, Embase <1980 to 2015 Week 31>, All Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>

Search Strategy:

| 1 | Clostridium difficile/ (17125) |

| 2 | Enterocolitis, Pseudomembranous/ (11520) |

| 3 | Clostridium Infections/ (6439) |

| 4 | (clostridium difficile or c difficile or c diff or clostridium enterocolitis or ((pseudomembranous or antibiotic associated) adj2 (enteritis or colitis or enterocolitis)) or clostridium infection*).tw. (26426) |

| 5 | or/1–4 (37451) |

| 6 | exp Feces/ (125412) |

| 7 | Microbiota/ (12302) |

| 8 | (((fecal or faecal or feces or faeces or stool or stools or microbiota*) adj4 (transplant* or transfus* or transfer* or infusion* or donor* or donation* or therap* or suspension)) or FMT or bacteriotherap* or human probiotic infus* or intestinal microbiome restorat*).tw. (5976) |

| 9 | or/6–8 (141194) |

| 10 | Diarrhea/th [Therapy] (6333) |

| 11 | or/9–10 (147157) |

| 12 | 5 and 11 (4290) |

| 13 | exp Animals/ not (exp Animals/ and Humans/) (8230594) |

| 14 | 12 not 13 (3972) |

| 15 | economics/ (247193) |

| 16 | economics, medical/ or economics, pharmaceutical/ or exp economics, hospital/ or economics, nursing/ or economics, dental/ (697761) |

| 17 | economics.fs. (369069) |

| 18 | (econom* or price or prices or pricing or priced or discount* or expenditure* or budget* or pharmacoeconomic* or pharmaco-economic*).tw. (636474) |

| 19 | exp “costs and cost analysis”/ (485810) |

| 20 | cost*.ti. (219098) |

| 21 | cost effective*.tw. (228512) |

| 22 | (cost* adj2 (util* or efficacy* or benefit* or minimi* or analy* or saving* or estimate* or allocation or control or sharing or instrument* or technolog*)).ab. (142978) |

| 23 | models, economic/ (127076) |

| 24 | markov chains/ or monte carlo method/ (116078) |

| 25 | (decision adj1 (tree* or analy* or model*)).tw. (31046) |

| 26 | (markov or markow or monte carlo).tw. (92331) |

| 27 | quality-adjusted life years/ (26021) |

| 28 | (QOLY or QOLYs or HRQOL or HRQOLs or QALY or QALYs or QALE or QALEs).tw. (44560) |

| 29 | ((adjusted adj (quality or life)) or (willing* adj2 pay) or sensitivity analys*s).tw. (87840) |

| 30 | or/15–29 (2151007) |

| 31 | 14 and 30 (196) |

| 32 | limit 31 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,DARE; records were retained] (187) |

| 33 | 32 use pmoz,cctr,coch,dare,clhta (76) |

| 34 | 14 use cleed (4) |

| 35 | or/33–34 (80) |

| 36 | peptoclostridium difficile/ (792) |

| 37 | Clostridium difficile infection/ (6854) |

| 38 | Clostridium infection/ (6534) |

| 39 | pseudomembranous colitis/ (11699) |

| 40 | (clostridium difficile or c difficile or c diff or clostridium enterocolitis or ((pseudomembranous or antibiotic associated) adj2 (enteritis or colitis or enterocolitis)) or clostridium infection*).tw. (26426) |

| 41 | or/36–40 (37153) |

| 42 | feces/ (120591) |

| 43 | feces microflora/ (4077) |

| 44 | (((fecal or faecal or feces or faeces or stool or stools or microbiota*) adj4 (transplant* or transfus* or transfer* or infusion* or donor* or donation* or therap* or suspension)) or FMT or bacteriotherap* or human probiotic infus* or intestinal microbiome restorat*).tw. (5976) |

| 45 | or/42–44 (128701) |

| 46 | diarrhea/th [Therapy] (6333) |

| 47 | or/45–46 (134663) |

| 48 | 41 and 47 (4281) |

| 49 | (exp animal/ or nonhuman/) not exp human/ (9407210) |

| 50 | 48 not 49 (3934) |

| 51 | Economics/ (247193) |

| 52 | Health Economics/ or exp Pharmacoeconomics/ (209005) |

| 53 | Economic Aspect/ or exp Economic Evaluation/ (375018) |

| 54 | (econom* or price or prices or pricing or priced or discount* or expenditure* or budget* or pharmacoeconomic* or pharmaco-economic*).tw. (636474) |

| 55 | exp “Cost”/ (485810) |

| 56 | cost*.ti. (219098) |

| 57 | cost effective*.tw. (228512) |

| 58 | (cost* adj2 (util* or efficacy* or benefit* or minimi* or analy* or saving* or estimate* or allocation or control or sharing or instrument* or technolog*)).ab. (142978) |

| 59 | Monte Carlo Method/ (47283) |

| 60 | (decision adj1 (tree* or analy* or model*)).tw. (31046) |

| 61 | (markov or markow or monte carlo).tw. (92331) |

| 62 | Quality-Adjusted Life Years/ (26021) |

| 63 | (QOLY or QOLYs or HRQOL or HRQOLs or QALY or QALYs or QALE or QALEs).tw. (44560) |

| 64 | ((adjusted adj (quality or life)) or (willing* adj2 pay) or sensitivity analys*s).tw. (87840) |

| 65 | or/51–64 (1759792) |

| 66 | 50 and 65 (171) |

| 67 | limit 66 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,DARE; records were retained] (162) |

| 68 | 67 use emez (98) |

| 69 | 35 or 68 (178) |

| 70 | remove duplicates from 69 (152) |

| 71 | 69 use pmoz (72) |

| 72 | 69 use emez (98) |

| 73 | 69 use cctr (0) |

| 74 | 69 use coch (2) |

| 75 | 69 use dare (1) |

| 76 | 69 use clhta (1) |

| 77 | 69 use cleed (4) |

Appendix 2: Evidence Quality Assessment

Table A1:

AMSTAR Scores of Included Systematic Reviews