Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive brain disease. Accurate diagnosis of AD and its prodromal stage, mild cognitive impairment, is crucial for clinical trial design. There is also growing interests in identifying brain imaging biomarkers that help evaluate AD risk presymptomatically. Here, we applied a recently developed multivariate tensor-based morphometry (mTBM) method to extract features from hippocampal surfaces, derived from anatomical brain MRI. For such surface-based features, the feature dimension is usually much larger than the number of subjects. We used dictionary learning and sparse coding to effectively reduce the feature dimensions. With the new features, an Adaboost classifier was employed for binary group classification. In tests on publicly available data from the Alzheimers Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the new framework outperformed several standard imaging measures in classifying different stages of AD. The new approach combines the efficiency of sparse coding with the sensitivity of surface mTBM, and boosts classification performance.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, multivariate tensor-based morphometry, dictionary learning and sparse coding

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimers disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease in which amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles accumulate in the brain. The most common early symptom is the difficulty remembering recent events (short-term memory loss). As the disease advances, patients may lack motivation, have problems with self-care, and may show behavioral abnormalities or even withdraw from family and society [3]. AD has a typical pattern of progression, with changes in the brain that correspond to the types and severity of symptoms. Disease progression is commonly divided into three main stages: asymptomatic normal aging (i.e., healthy controls; CTL), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD. All of these classifications are defined clinically based on behavioral and cognitive assessments. Although a person with MCI has elevated risk of developing AD, many people with MCI remain stable for some time or develop other degenerative conditions pathologically distinct or partially overlapping with AD. Besides, some normal elderly people have elevated risk of developing MCI, but others may remain stable or even develop AD after only one year of the onset to MCI.

To diagnose different stages of disease, computer-aided diagnostic classification is increasingly popular in neuroimaging, especially given the vast number of features available to assist diagnosis in a 3D brain image [26]. Understanding which brain imaging features are best for diagnostic classification is also of increased interests. An important question for diagnostic classification based on voxel-based or surface-based morphometric maps is which statistics are best to analyze. Statistics derived from anatomical surface models, such as radial distances (RD, distances from the medial core to each surface point) [15, 23], spherical harmonic analysis [22, 7], local area differences (related to the determinant of the Jacobian matrix) [29], and Gaussian random fields [2] have all been applied to analyze the shape and geometry of various brain structures. Surface tensor-based morphometry (TBM) [6, 4] is an intrinsic surface statistic that examines spatial derivatives of the deformation maps that register brains to common template and construct morphological tensor maps. In recent studies, surface multivariate TBM (mTBM) [27, 25] was found to be more sensitive for detecting group differences than other standard TBM-based statistics. In this work, we evaluated the potential of surface mTBM and RD as imaging biomarkers for AD diagnosis and prognosis research.

In this context, when we applied three-dimensional statistical maps to classification, the feature dimension is usually much larger than the number of subjects, i.e. the so-called “high dimension, small sample size problem”. When a vast number of variables are measured from a small number of subjects, it is often necessary to reduce their dimensions. There are two main approaches for this: feature selection and feature extraction. Feature selection reduces the feature dimension by selecting a subset of original variables [9]. Feature extraction reduces the dimension based on mathematical projections, which transform the original features into a lower dimensional but more appropriate feature space [8]. Because of the low accuracy of image content recognition based on global features, sparse coding has been proposed to use a small number of basis vectors to represent local features effectively and concisely [13]. Recently, sparse learning has increasingly been applied in neuroimaging to study genetic influences on the brain, functional connectivity and for outcome predictions [24, 21, 26].

In this paper, we developed a novel approach, based on surface fluid registration, radial distance, mTBM, and dictionary learning and sparse coding, to study hippocampal morphometry for AD diagnosis. We hypothesized that our surface multivariate statistics combined with sparse learning might improve the accuracy for classification based on neuroimaging data. We tested our hypothesis on the ADNI dataset used in our prior work [20] and studied three different classification problems. The results showed that our new method achieved better performance than several standard measures, on all three different classification tasks.

2. MULTIVARIATE SURFACE TENSOR-BASED MORPHOMETRY

We have studied surface mTBM in our prior work, e.g. [27, 20]. In general, surface mTBM involves two steps. In the first step, a nonlinear surface registration method, such as surface fluid registration [20], or a constrained harmonic map [27, 26], is applied to register each individual surface to a common template surface. Following that, a set of multivariate statistics are computed by analyzing the local deformations.

Suppose ϕ = S1 → S2 is a map from surface S1 to surface S2. The derivative map of ϕ is the linear map between the tangent spaces dϕ : TM(p) → TM(ϕ(p)), induced by the map ϕ, which also defines the Jacobian matrix of ϕ. The derivative map dϕ is approximated by the linear map from one face [v1, v2, v3] to another one [w1, w2, w3]. First, we isometrically embed the triangles [v1, v2, v3] and [w1, w2, w3] onto the plane R2. Let vi, wi, i = 1, 2, 3 to represent the 3D position of points vi, wi, i = 1, 2, 3. Then, the derivative map J can be computed by

| (1) |

Based on the derivative map, J, we define the deformation tensors as S = (JT J)1/2. Instead of analyzing shape differences based on the eigenvalues of the deformation tensor, we consider a new family of metrics, the “Log-Euclidean metrics” [1]. These metrics make computations on tensors easier to perform, as the transformed values form a vector space, and statistical parameters can then be computed easily using standard formulae for Euclidean spaces.

As S is a positive-definite symmetric matrix, the logarithm of the deformation tensor S analyzed in mTBM has 3 independent components. Besides these, we also adopted the radial distance(RD) [15, 23] as an additional feature. RD measures the shortest distance between every surface point and the middle axis of a tube-shape surface. The intuition is that mTBM describes the surface deformation along the surface tangent plane while RD reflects surface differences along the surface normal directions.

3. DICTIONARY LEARNING AND SPARSE CODING

For a classification algorithm based on 3D images or surface-based features, the feature dimension is usually much larger than the number of subjects, e.g., mTBM features. In this paper, we used the technique of dictionary learning and sparse coding [12] to reduce the dimension before prediction. Dictionary learning has been successful in many image processing tasks as it can concisely model natural image patches. Stochastic Coordinate Coding (SCC) [11] was adopted to construct the dictionary because of its computation efficiency.

Given a finite training set of signals X = (x1, x2, ⋯, xn) in Rp×n image patches, each image patch xi ϵ, Rp, i = 1, 2, ⋯, n, where p is the dimension of image patch, we aim to optimize the empirical cost function

| (2) |

where D ϵ Rp×m is the dictionary, each column representing a basis vector, and l is a loss function such that l(x, D) should be small if D is “good” at representing the signal x.

Specifically, suppose there are m atoms dj ϵ Rp, j = 1, 2, ⋯ , m, where the number of atoms is much smaller than n (the number of image patches) but larger than p (the dimension of the image patches). xi can be represented into . In this way, the p-dimensional vector xi is represented by an m-dimensional vector zi = (zi,1, ⋯ , zi,m)T, which means the learned feature vector zi is a sparse vector.

Then, we can incorporate the idea of sparse patch features into the following optimization problem for each patch xi:

| (3) |

where λ is the regularization parameter, ∥ · ∥ is the standard Euclidean norm and . The first term of Eq. 3 measures the degree of goodness representing the image patches. The second term ensures the sparsity of the learned feature zi. D = (d1, d2, ⋯ , dm) ϵ Rp×m is the dictionary. To prevent an arbitrary scaling of the sparse codes, the columns di are constrained by

| (4) |

Thus, the problem of dictionary learning can be rewritten as a matrix factorization problem as follows:

| (5) |

It is a non-convex problem with respect to joint parameters in the dictionary D and the sparse codes Z. However, it is a convex problem when either D or Z is fixed. When the dictionary D is fixed, solving each sparse code zi is a Lasso problem. But because the hippocampal feature dimension m is much larger than n, solving the Lasso problem might be time-consuming. On the other hand, when the sparse codes are fixed, it will become a quadratic problem. Solving the sparse coding problem also requires a lot of time when dealing with large-scale data sets and a large size dictionary. Thus, we choose the SCC algorithm [11], which can dramatically reduce the computational cost of the sparse coding while keeping a comparable performance.

4. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

4.1. Data Description

Data used in this work were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) project [28]. At the time of downloading (09/2010), the baseline dataset consisted of 843 adults, aged 55 to 90, including 233 elderly healthy controls (CTL), 410 subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and 200 AD patients. In this work, we studied a total of 810 subjects, the same dataset used in our priori work [20]. Within this population, there were 228 CTL people, 194 AD subjects, and 388 MCI patients. Among the 810 subjects, 142 MCI patients converted to AD within 48 months, which we called MCI converters. And 39 CTL subjects converted to MCI within 48 months, which we called CTL converters.

4.2. Sparse Coding and Classification

After automatically segmenting the hippocampus with FSL [10] from brain MR images, we built parametric surface meshes to model hippocampal shapes. High-order correspondences between hippocampal surfaces were enforced across subjects with a novel inverse consistent surface fluid registration method [20]. Multivariate statistics consisting of mTBM and RD were computed for surface deformation analysis. In our study, each registered hippocampal surface has 15,000 vertices. On each vertex, we computed a set of multivariate statistics consisting of mTBM (3 × 1) and RD (1 × 1).

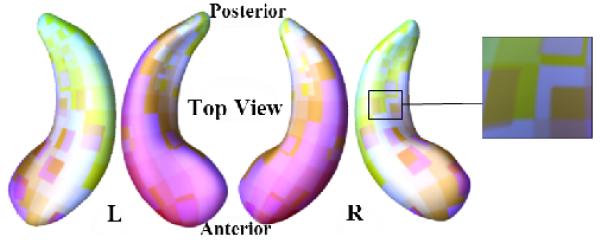

In total, we obtained a 4 × 1 feature vector on each point of two regular grids with 150 × 100 points on both left and right hippocampal surfaces from each subject. To extract useful surface features, we first randomly generated a number of 10 × 10 windows on each surface to obtain a collection of small image patches with different amounts of overlap. An example of an image patch collection is shown in Fig. 1. As these patches are overlapped, a vertex may be contained in several patches. For such an overlapping vertex, its value in the restructured mesh was obtained by averaging their counterparts from the centered patches. The procedure is in fact equivalent to applying a high-pass filter to the original mesh. As a result, the geometrical structures are still present in the centered mesh, but some low frequencies have disappeared. Finally, we transferred the original hippocampal surface features into 1008 overlapping patches. We initialized the dictionary via selecting random patches [5], which has been shown to be a very efficient method. Then we learned the dictionary and sparse codes by SCC using the initial dictionary [11]. All three experiments involved training for 10 epochs using a batch size of 1. When the dictionary and sparse codes were learned, we applied max pooling [18] to generate features for annotation. After feature reduction, the dataset was reduced to a reasonable size and classification was performed.

Fig. 1.

Visualization of computed image patches on a pair of hippocampal surfaces. The zoom-in picture shows some overlapping areas between image patches.

Like a “committee” of weak classifiers, classifier ensembles [16] may achieve more accuracy than any individual member classifier. In this work, we employed the Adaboost [17] to do the binary classification and discriminate between individuals in different groups. For comparison purposes, we also computed hippocampal volumes (Vol.) and surface areas (Area) within the MNI space model in each side of brain hemispheres [14]. The Parzen window classifier[19] with the linear kernel assuming a prevalence of 50% was applied to classify individuals based on volume and area data. An N-fold leave-one-out cross validation protocol was adopted to estimate classification accuracy. All subjects were randomly divided into N folds. The surface biomarkers were selected by training on N-1 folds and the test was performed on the remaining fold. We rotated this procedure for N times to estimate the accuracy.

We tested the new framework in three classification experiments, including (1) AD vs. CTL, (2) MCI converters vs. MCI non-converters, and (3) CTL converters vs. CTL non-converters. For the last task, to make the classification fair and not confounded, we selected 73 non-converter subjects with matched sex, age and initial memory scores. Details of selected subjects, including the training and testing subject numbers in each round, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistics of three experimental test data-sets.

| Group | #1 | #–1 | #Train | #Test | #Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD-CTL | 194 | 228 | 360 | 62 | 120000 |

| MCI C-NC | 142 | 246 | 207 | 181 | 120000 |

| CTL C-NC | 39 | 73 | 70 | 42 | 120000 |

4.3. Classification Results

The output of each classification experiment was compared to the ground truth, and a contingency table was computed to indicate how many class labels were correctly identified, as members of one of the two classes. The rows of the contingency table represent the true classes and the columns represent the assigned classes. The cell at row r and column c is the number of subjects whose true class is r while their assigned class is c. A possible combination of ground truth and predicted classification for two classes may be represented by a matrix Four performance measures: Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive predictive value, and Negative predictive value, were computed as follows: , , , . Besides them, we also computed the area-under-the-curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC). Tables 2,3,4 show classification performance in the three sets of experiments.

Table 2.

Results of AD vs. CTL

| Vol. | Area | RD | mTBM | RD+mTBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.81 |

| Sensitivity | 0.63 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Specificity | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.78 |

| Npv | 0.72 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.83 |

| AUC | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 0.78 |

Table 3.

Results of MCI Converters vs. Non-converters

| Vol. | Area | RD | mTBM | RD+mTBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| Sensitivity | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0 | 0.67 | 0.82 |

| Specificity | 0.73 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.76 |

| Npv | 0.84 | 0.82 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.95 |

| AUC | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.75 |

Table 4.

Results of CTL Converters vs. Non-converters

| Vol. | Area | RD | mTBM | RD+mTBM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.64 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.71 |

| Sensitivity | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 | 0.71 |

| Specificity | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 1 |

| Npv | 0.77 | 0.64 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| AUC | 0.57 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.67 |

In Table 2, the Area has the worst performance, when used alone. The sensitivity of RD is zero, which means that RD feature cannot generate a good classification between the AD and the healthy control group. It predicts all of the test cases to be negative. The mTBM, used on its own, performs better than the RD feature, but after several rounds of feature reductions, it performs not so well as the proposed multivariate statistics consisting of RD with mTBM. In Table 3, although the volume achieves a good performance on MCI converters vs. non-converters, the mTBM receives higher accuracy. Besides, our new method also improve the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity compared with other features or other methods. In Table 4, as the number of subjects becomes smaller and the morphometric differences between groups more subtle, the classification become even more challenging, only volume feature and the combined statistics achieved meaningful results. The results show that RD, mTBM and Area cannot be used to learn a good model, as they tend to classify all subjects into one class. The comparison also shows that our new framework selected better features and made better and more meaningful classifications.

Using our new framework, we achieved an accuracy of 0.81, 0.77, and 0.71 in the three experiments, respectively. Our work also achieved high sensitivity values: 0.83, 0.82, and 0.71, as well as reasonable specificity and AUC in all three experiments. Throughout all the experimental results, the best specificity, sensitivity and negative predictive value were achieved when we used RD+mTBM features.

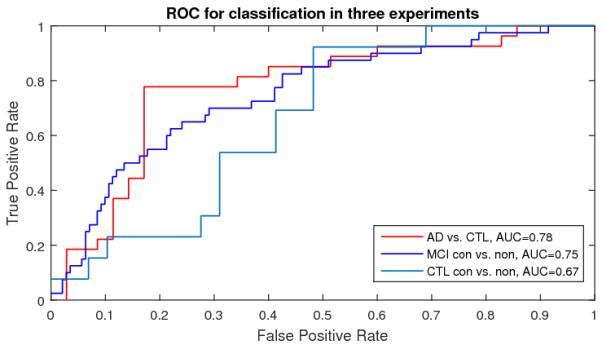

To further demonstrate our algorithm performance, we also generated ROC and computed AUC measures with our new multivariate statistics in Fig. 2. In Fig 2, AD vs. CTL achieved the best AUC measures (0.78). The comparison demonstrated that our new framework may be useful for AD diagnosis and prognosis research.

Fig. 2.

ROC for Classification with RD + mTBM features

5. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

In this paper, we present a novel framework that combines surface mTBM with dictionary learning and sparse coding to deal with high dimensional features before classification. We applied the Adaboost classifier to classify different AD stages. Our comprehensive experiments showed that our method achieve stable performance and higher accuracy than some standard morphometric measures. In the future, we will extend this framework to multi-label classification to better detect earlier stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

6. REFERENCES

- [1].Arsigny V, Fillard P, Pennec X, Ayache N. Log-Euclidean metrics for fast and simple calculus on diffusion tensors. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Aug;56(2):411–421. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bansal R, Staib LH, Xu D, Zhu H, Peterson BS. Statistical analyses of brain surfaces using Gaussian random fields on 2-D manifolds. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007 Jan;26(1):46–57. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.884187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burns A, Iliffe S. Alzheimer’s disease. BMJ. 2009;338:b158. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chung MK, Dalton KM, Davidson RJ. Tensor-based cortical surface morphometry via weighted spherical harmonic representation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2008 Aug;27(8):1143–1151. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.918338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Coates A, Ng AY. The importance of encoding versus training with sparse coding and vector quantization. Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-11).2011. pp. 921–928. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Davatzikos C, Vaillant M, Resnick SM, Prince JL, Letovsky S, Bryan RN. A computerized approach for morphological analysis of the corpus callosum. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20(1):88–97. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199601000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gutman B, Wang Y, Morra J, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Disease classification with hippocampal shape invariants. Hippocampus. 2009 Jun;19(6):572–578. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guyon I, Gunn S, Nikravesh M, Zadeh LA. Feature extraction: foundations and applications. ume 207. Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jain A, Zongker D. Feature selection: Evaluation, application, and small sample performance. Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, IEEE Transactions on. 1997;19(2):153–158. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens T, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lin B, Li Q, Sun Q, Lai M, Davidson I, Fan W, Ye J. Stochastic Coordinate Coding and Its Application for Drosophila Gene Expression Pattern Annotation. arXiv preprint arX-iv:1407.8147. 2014.

- [12].Mairal J, Bach F, Ponce J, Sapiro G. Online dictionary learning for sparse coding. Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML ′09; New York, NY, USA. 2009; ACM; pp. 689–696. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Olshausen BA, Field DJ. Sparse coding with an over-complete basis set: A strategy employed by v1? Vision research. 1997;37(23):3311–3325. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Patenaude B, Smith SM, Kennedy DN, Jenkinson M. A bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):907–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pizer SM, Fritsch DS, Yushkevich PA, Johnson VE, Chaney EL. Segmentation, registration, and measurement of shape variation via image object shape. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999 Oct;18(10):851–865. doi: 10.1109/42.811263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rodriguez JJ, Kuncheva LI, Alonso CJ. Rotation forest: A new classifier ensemble method. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2006 Oct;28(10):1619–1630. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2006.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rojas R. Adaboost and the super bowl of classifiers a tutorial introduction to adaptive boosting. Freie University; Berlin: 2009. Tech. Rep. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Scherer D, Müller A, Behnke S. Artificial Neural Networks–ICANN 2010. Springer; 2010. Evaluation of pooling operations in convolutional architectures for object recognition; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shawe-Taylor J, Cristianini N. Kernel methods for pattern analysis. Cambridge university press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shi J, Thompson PM, Gutman B, Wang Y. Surface fluid registration of conformal representation: application to detect disease burden and genetic influence on hippocampus. Neuroimage. 2013 Sep;78:111–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stonnington CM, Chu C, Kloppel S, Jack CR, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS. Predicting clinical scores from magnetic resonance scans in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2010 Jul;51(4):1405–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Styner M, Lieberman JA, McClure RK, Weinberger DR, Jones DW, Gerig G. Morphometric analysis of lateral ventricles in schizophrenia and healthy controls regarding genetic and disease-specific factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005 Mar;102(13):4872–4877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501117102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, De Zubicaray GI, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, Hong MS, Herman DH, Gravano D, Doddrell DM, Toga AW. Mapping hippocampal and ventricular change in Alzheimer disease. Neuroimage. 2004 Aug;22(4):1754–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vounou M, Nichols TE, Montana G. Discovering genetic associations with high-dimensional neuroimaging phenotypes: A sparse reduced-rank regression approach. Neuroimage. 2010 Nov;53(3):1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang Y, Song Y, Rajagopalan P, An T, Liu K, Chou Y, Gutman B, Toga AW, Thompson PM, Initiative ADN, et al. Surface-based tbm boosts power to detect disease effects on the brain: an n= 804 adni study. Neuroimage. 2011;56(4):1993–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang Y, Yuan L, Shi J, Greve A, Ye J, Toga AW, Reiss AL, Thompson PM. Applying tensor-based morphometry to parametric surfaces can improve MRI-based disease diagnosis. Neuroimage. 2013 Jul;74:209–230. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang Y, Zhang J, Gutman B, Chan TF, Becker JT, Aizenstein HJ, Lopez OL, Tamburo RJ, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Multivariate tensor-based morphometry on surfaces: application to mapping ventricular abnormalities in HIV/AIDS. Neuroimage. 2010 Feb;49(3):2141–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Cairns NJ, Cedarbaum J, Green RC, Harvey D, Jack CR, Jagust W, et al. 2014 update of the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative: A review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2015;11(6):e1–e120. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Woods RP. Characterizing volume and surface deformations in an atlas framework: theory, applications, and implementation. Neuroimage. 2003 Mar;18(3):769–788. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]