BACKGROUND

As the US population ages, the use of anti-platelet medications for the prophylaxis and treatment of stroke and heart disease is steadily increasing.1,2 Prior studies suggest that patients with pre-injury anti-platelet use are at increased risk for mortality following blunt head trauma and traumatic intracranial hemorrhage (tICH).2–4 Rapid control of hemorrhage in tICH is important, since the majority of expansion occurs in the first 24 hours after injury and hemorrhage expansion is an independent risk factor for mortality.5–8 It is proposed that this increased risk for mortality among patients with pre-injury anti-platelet use may be related to impaired platelet function.9

Transfusion of platelets has been suggested as a means to counteract the anti-platelet effects of clopidogrel and aspirin.10 Many institutions have implemented protocols for platelet transfusion for the reversal of anti-platelet medications in the presence of tICH.11 However, it is unclear whether this practice is based on evidence demonstrating improved patient-oriented outcomes. In adult patients with pre-injury oral anti-platelet use and tICH, does urgent transfusion of platelets within 24 hours of injury, improve patient-oriented outcomes such as mortality or neurological outcomes, compared to no platelet transfusion?

METHODS

Anti-platelet agents of interest included: aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlodipine, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. We did not include non-oral agents such as abcixamab or eptifibatide, nor did we include other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents such as ibuprofen or naproxen, due to the short duration of their anti-platelet effects.12 We did not limit our inclusion criteria to any specific dose of platelet transfusion and included studies that transfused platelets to tICH patients in the intervention group regardless of the dose of platelets.

We restricted platelet transfusions to the first 24 hours post injury since the majority of hematoma progression occurs within this period.5,6 However, we did not exclude the study if it did not report the timing of platelet transfusion.

Participants

Participants were adult (18 years or older) ED patients with pre-injury oral anti-platelet use and tICH. The presence of tICH is defined as intracranial hemorrhage or contusion evident on computed tomography (CT) scan or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of head.

Intervention

Intervention consisted of transfusion of platelets at any dose, within 24 hours of injury. This was compared to a strategy of no platelet transfusion (control group).

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was mortality from all causes, assessed at the end of the follow-up period scheduled by each study. Additional primary outcome measures included neurological outcome measures by any method such as Glasgow Outcome Score Extended (GOS-E).13 Secondary outcome measures included transfusion related morbidity including infection, transfusion related lung injury (TRALI), and transfusion reaction.

Target study design

We targeted peer-reviewed, randomized clinical trials or observational studies that compared platelet transfusion to no transfusion and reported the primary outcome measure.

SEARCH AND SELECTION METHODS

We searched the MEDLINE database from 1966 to August 2011 and the EMBASE database from 1980 to August 2011. Additional databases searched included the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We reviewed the bibliographies of pertinent articles for citations of eligible studies. Our MEDLINE search strategy is presented in the Appendix.

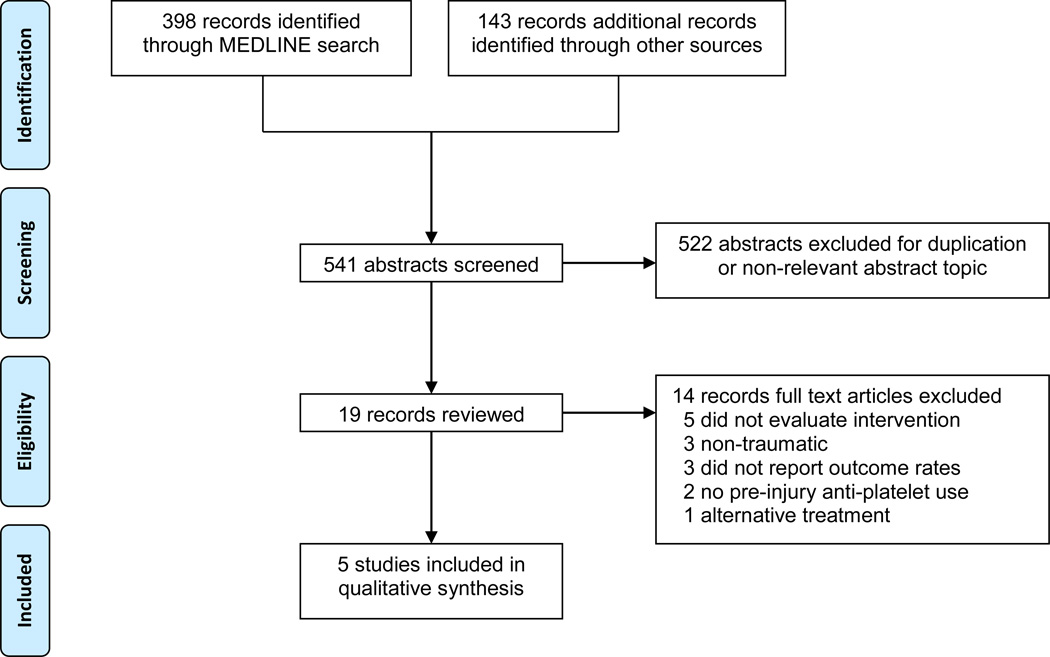

Two authors (DN and JB) used an algorithm with selection criteria to identify eligible studies (Figure). They extracted data from eligible studies using a standardized worksheet. If disagreement arose, three authors (DN, JB, SZ) conferred to reach consensus. When relevant data from a study were missing or unclear, we attempted to contact the primary author.

Figure.

Flowchart representing the selection process for the included trials.

The search strategy identified a total of 541 studies from the databases (Figure). A total of 19 full text articles were reviewed. Fourteen articles were excluded. 2,9,14–25. A total of five studies met our inclusion criteria.3,4,26–28 Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the review.

| Study | Setting | Design | Patients | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downey et al, 2010 | Two US, Level1 trauma centers |

Retrospective registry review; Jan 2003–Dec 2006 |

328 patients, age ≥ 50 years old with tICH and pre-injury aspirin and/or clopidogrel Excluded: none (concomitant warfarin not excluded) |

Transfusion of 6 units of concentrated platelets (unknown time after injury) |

Standard care | In-hospital mortality |

| Washington et al, 2011 | Single, US, Level 1 trauma center |

Retrospective registry review; Jan 2007–Dec 2008 |

108 patients with mild traumatic brain injury (GCS≥13 and ICH on CT scan) on anti-platelet agents. Excluded: patients who required immediate operative intervention and patients with coagulopathy |

Transfusion of platelets (unknown dosing and timing) |

Standard care | In-hospital mortality, neurological* or medical decline**, requirement of neurosurgical intervention***, and discharge Glasgow Outcome Scale. |

| Ivascu et al, 2008 | Single, US, Level 1 trauma center |

Retrospective registry review; Aug 1999–Nov 2004 |

109 patients with tICH and pre-injury aspirin and/or clopidogrel Excluded: none (concomitant warfarin not reported) |

Transfusion of platelets (unknown dosing and timing) |

Standard care | In-hospital mortality |

| Ohm et al, 2005 | Single, US, Level 1 trauma center |

Retrospective registry review; Jan 1999–Dec 2002 |

90 patients, age ≥ 50 years old with tICH and pre-injury aspirin and/or clopidogrel Excluded: none (concomitant warfarin not reported) |

Transfusion of platelets (unknown dosing) in first 24 hours after injury |

Standard care | In-hospital mortality |

| Wong et al, 2008 | Single, US, Level 2 trauma center |

Retrospective registry review; Jan 2001–Dec 2005 |

111 patients with tICH and pre-injury aspirin and/or clopidogrel Excluded: none (concomitant warfarin not reported) |

Transfusion of platelets (unknown dosing and timing) |

Standard care | In-hospital mortality |

Abbreviations: tICH, traumatic intracranial hemorrhage; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; CT scan, computed tomography scan

Neurological decline defined as an increase in monitoring requirement or intervention because of a decline in mental status or development of a focal neurologic deficit attributable to injury visualized on imaging.

Medical decline defined as an increase in monitoring or intervention because of cardiac, pulmonary, or renal decline.

Neurosurgical interventions included craniotomy, craniectomy, placement of intracranial pressure monitor, and placement of an external ventricular drain.

QUALITY ASSESSMENT

We used the “Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation” (GRADE) criteria to assess the limitations of the studies and the risk of bias in the reported results.29

The primary limitation in included studies was related to the failure to adequately control for confounding factors and to measure all known prognostic factors. All but one study reported key prognostic variables between cohorts. One study adjusted outcomes for differences in prognostic variables.26 Due to the overall limitation of comparability of cohorts, included studies were given a very low to low quality of evidence grade.29

RESULTS

DESCRIPTION OF STUDIES

All five studies had a retrospective chart review design based on cases identified in trauma registry. Two studies were performed with the primary research question matching our research question (outcome of patients with pre-injury anti-platelet use and tICH with and without platelet transfusion).26,28 The other three studies had different primary research questions, such as identifying the predictors of mortality in tICH/antiplatelet patients27 or the impact of antiplatelet use on outcome of tICH/antiplatelet patients3,4 but performed their study on subjects similar to our population of interest. We were able to extract the necessary data from the latter studies either directly from the manuscripts or by contacting the authors.

RESULTS

A total of 635 patients with pre-injury anti-platelet use and tICH were enrolled in the included studies. All studies reported in-hospital mortality. A comparison of mortality rates in patients with and without platelet transfusion is presented in Table 2. Due to heterogeneity between studies, we did not perform a meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the included studies, comparing mortality rates in patients on antiplatelet therapy and receiving platelet transfusion versus standard care.

| Study | Transfusion of platelets No. (%) [95% CI] of Patients |

Standard care No. (%) [95% CI] of Patients |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

NNTa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downey et al, 2010 | 29/166 (17.5) [12.5–24.0] | 27/162 (16.7) [11.7–23.2] | 1.04 (0.65–1.69) | - |

| Washington et al, 2011 | 2/44 (5%) [1.3–15.0] | 0/64 (0%) [0–5.6] | - | - |

| Ivascu et al, 2008 | 11/40 (27.5) [16.1–42.8] | 9/69 (13.0) [7.0–23.0] | 2.12 (0.96–4.65) | - |

| Ohm et al, 2005 | 10/24 (41.7) [24.5–61.2] | 11/64 (17.2) [9.9–28.2] | 2.42 (1.18–4.96) | 4 (2 to 25)$ |

| Wong et al, 2008b | 3/92 (3.4) [1.2–9.5] | 3/19 (15.5% )[3.4–39.6] | 0.21 (0.05–0.95) | 7 (3 to 145) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NNT, number need to treat.

Number needed to treat (NNT) was only calculated when the difference between the groups was statistically significant, meaning that the confidence interval for the relative risk did not cross 1.

Additional data provided by author.

Number Needed to Harm

The largest study by Downey et al, showed no difference between treatment and control groups (relative risk [RR] 10.04, 95% confidence intervals [CI] 0.65–1.69).26 A high number of patients had concomitant warfarin use (89% of study group and 80% of the control group). The authors of this study report fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusion in a small number of patients (27/328) but do not provide the group assignments. Patients in the platelet transfusion group were older and more likely to be on warfarin or clopidogrel. However, adjusting for these variables did not impact the relationship between mortality and platelet transfusion in the subjects.

No benefit in mortality was observed in patients receiving platelet transfusion in the study by Washington et al.28 The spectrum of patients were more narrow in this study since the investigators only enrolled patients with mild traumatic brain injury (GCS ≥13 and tICH) and excluded patients who required surgical interventions such as those with epidural hematoma). This study excluded patients who were on warfarin but does not report the number of patients who received FFP.

Ivascu et al demonstrated a trend towards increased mortality in the treatment group (RR 2.12, 95% CI 0.96–4.65).27 They did not report concomitant warfarin use but did report a mean INR of 1.1 for both study and control groups. The number of patients who were transfused FFP was not reported.

Ohm et al showed an unadjusted increase in mortality in the platelet transfusion group (RR 2.42, 95% CI 1.18–4.96).3 The subjects in this study were classified based on presence or absence of anti-platelet therapy and not based on platelet transfusion, thus we were unable to compare prognostic variables between the groups.

Only Wong et al showed improved unadjusted in-hospital mortality in patients receiving platelet transfusion (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.05–0.95).4 The primary analysis of this study was based on the presence or absence of pre-injury anti-platelet use rather than platelet transfusion. There was a large difference between the number of patients in the two groups (92 in the transfusion cohort and 19 in the usual care cohort), suggesting that the cohorts were likely different despite comparability in age, GCS, and Injury Severity Score (ISS).

No study reported neurocognitive outcomes or transfusion related morbidity.

DISCUSSION

Aspirin and clopidogrel are by far the most commonly prescribed anti-platelet drugs.1 Both clopidogrel and aspirin render platelets dysfunctional and inhibit aggregation.26,27,30 Drug related platelet dysfunction in head injured patients has been associated with larger degrees of intracranial hemorrhage and worse outcomes compared to patients without pre-injury anti-platelet use.2–4 This effect appears greater with adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor inhibitors (i.e., clopidogrel) compared to aspirin, which imposes its effect on platelet function through the cycloxygenase pathway.30

It has been postulated that platelet transfusion can restore platelet function and thus limit hemorrhage progression.10 Studies have shown that in patients with non-traumatic bleeds, infusion of platelets increases the platelet activity in vivo.19,30,31 One unit of single donor apheresis platelets (most common type used in the US) or six units of multiple donor whole blood-derived platelets administered to a normal sized adult raises the platelet count by approximately 30,000/microliter at one hour after the infusion with increased platelet activity seen almost immediately.31

However, in vitro studies testing platelet aggregation after clopidogrel reveal that about 40–60% of platelets remain dysfunctional at steady-state after platelet transfusion and an infusion of 12.5 units of pooled platelets might be needed to achieve full normalization of platelet function.32 It is not clear whether full platelet functional recovery is necessary to achieve a clinically significant improvement. Moreover, patients may have varied responses to anti-platelet medications.19 Measurements of platelet function (e.g., PFA-100) may further evaluate this heterogeneity.

Our study has a number of limitations. Only two of the included studies had designed their studies to address the research question posed by this EBM review. This issue limits the comparability of groups (anti-platelet transfusion versus routine care). All included studies were based on registry data and thus suffer from limitations inherent to retrospective analysis of a secondary data set.33 Studies failed to control for confounding variables (e.g., concomitant warfarin use) between treatment and routine care cohorts. Even with attempts to adjust for differences in baseline prognostic variables, it is probable that significant bias existed in the decision to transfuse platelets or not. Our primary outcome measures were all-cause mortality and neurological outcomes. An alternative outcome measure might include mortality from brain injury. None of the included studies used this alternative outcome measure. Finally, the included studies provided limited information regarding the timing of transfusion after injury which may impact outcomes.

The potential benefits of platelet transfusion must be balanced by the potential harm. The risks of platelet transfusion include infection, ABO-mismatch, alloimmunization, and refractoriness to transfusion. Clinicians may be more apt to transfuse patients that are at a higher risk for bleeding or with have more significant injuries. Conversely, clinicians may consider transfusion futile in patients with very poor prognosis.

CONCLUSION

Five retrospective registry studies with suboptimal methodologies provide inadequate evidence to support the routine use of platelet transfusion in adult ED patients with pre-injury anti-platelet use and tICH.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Nishijima had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong

Acquisition of data: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong

Analysis and interpretation of data: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong, Legome

Drafting of the manuscript: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong, Legome

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong, Legome

Statistical analysis: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong

Administrative, technical, or material support: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong

Study supervision: Nishijima, Zehtabchi, Berrong

REFERENCES

- 1.Patrono C, Coller B, FitzGerald GA, Hirsh J, Roth G. Platelet-active drugs: the relationships among dose, effectiveness, and side effects: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126:234S–264S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.234S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones K, Sharp C, Mangram AJ, Dunn EL. The effects of preinjury clopidogrel use on older trauma patients with head injuries. Am J Surg. 2006;192:743–745. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohm C, Mina A, Howells G, Bair H, Bendick P. Effects of antiplatelet agents on outcomes for elderly patients with traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 2005;58:518–522. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000151671.35280.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong DK, Lurie F, Wong LL. The effects of clopidogrel on elderly traumatic brain injured patients. J Trauma. 2008;65:1303–1308. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318185e234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narayan RK, Maas AI, Servadei F, Skolnick BE, Tillinger MN, Marshall LF. Progression of traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage: a prospective observational study. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:629–639. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oertel M, Kelly DF, McArthur D, Boscardin WJ, Glenn TC, Lee JH, Gravori T, Obukhov D, McBride DQ, Martin NA. Progressive hemorrhage after head trauma: predictors and consequences of the evolving injury. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:109–116. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.1.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang EF, Meeker M, Holland MC. Acute traumatic intraparenchymal hemorrhage: risk factors for progression in the early post-injury period. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:222–230. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000279217.45881.69. discussion 230-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chieregato A, Fainardi E, Morselli-Labate AM, Antonelli V, Compagnone C, Targa L, Kraus J, Servadei F. Factors associated with neurological outcome and lesion progression in traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:671–680. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156200.76331.7a. discussion 671-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nekludov M, Bellander BM, Blomback M, Wallen HN. Platelet dysfunction in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1699–1706. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMillian WD, Rogers FB. Management of prehospital antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in traumatic head injury: a review. J Trauma. 2009;66:942–950. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181978e7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell PG, Sen A, Yadla S, Jabbour P, Jallo J. Emergency reversal of antiplatelet agents in patients presenting with an intracranial hemorrhage: a clinical review. World Neurosurg. 74:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catella-Lawson F, Reilly MP, Kapoor SC, Cucchiara AJ, DeMarco S, Tournier B, Vyas S, Fitzgerald GA. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and the antiplatelet effects of aspirin. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1809–1817. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15:573–585. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brewer ES, Reznikov B, Liberman RF, Baker RA, Rosenblatt MS, David CA, Flacke S. Incidence and predictors of intracranial hemorrhage after minor head trauma in patients taking anticoagulant and antiplatelet medication. J Trauma. 70:E1–E5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e5e286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tauber M, Koller H, Moroder P, Hitzl W, Resch H. Secondary intracranial hemorrhage after mild head injury in patients with low-dose acetylsalicylate acid prophylaxis. J Trauma. 2009;67:521–525. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a7c184. discussion 525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talving P, Benfield R, Hadjizacharia P, Inaba K, Chan LS, Demetriades D. Coagulopathy in severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. J Trauma. 2009;66:55–61. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318190c3c0. discussion 61-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spektor S, Agus S, Merkin V, Constantini S. Low-dose aspirin prophylaxis and risk of intracranial hemorrhage in patients older than 60 years of age with mild or moderate head injury: a prospective study. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:661–665. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ducruet AF, Hickman ZL, Zacharia BE, Grobelny BT, DeRosa PA, Landes E, Lei S, Khandji J, Gubrod S, Connolly ES. Impact of platelet transfusion on hematoma expansion in patients receiving antiplatelet agents before intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Res. 32:706–710. doi: 10.1179/174313209X459129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naidech AM, Bernstein RA, Levasseur K, Bassin SL, Bendok BR, Batjer HH, Bleck TP, Alberts MJ. Platelet activity and outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:352–356. doi: 10.1002/ana.21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolini A, Ghirarduzzi A, Iorio A, Silingardi M, Malferrari G, Baldi G. Intracranial bleeding: epidemiology and relationships with antithrombotic treatment in 241 cerebral hemorrhages in Reggio Emilia. Haematologica. 2002;87:948–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortuna GR, Mueller EW, James LE, Shutter LA, Butler KL. The impact of preinjury antiplatelet and anticoagulant pharmacotherapy on outcomes in elderly patients with hemorrhagic brain injury. Surgery. 2008;144:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.06.009. discussion 603-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnuriger B, Inaba K, Abdelsayed GA, Lustenberger T, Eberle BM, Barmparas G, Talving P, Demetriades D. The impact of platelets on the progression of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma. 68:881–885. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d3cc58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrick MM, Tyroch AH, Youens CA, Handley T. Subsequent development of thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy in moderate and severe head injury: support for serial laboratory examination. J Trauma. 2005;58:725–729. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000159249.68363.78. discussion 729-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engstrom M, Romner B, Schalen W, Reinstrup P. Thrombocytopenia predicts progressive hemorrhage after head trauma. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:291–296. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knudson MM, Cohen MJ, Reidy R, Jaeger S, Bacchetti P, Jin C, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Trauma, transfusions, and use of recombinant factor VIIa: A multicenter case registry report of 380 patients from the Western Trauma Association. J Am Coll Surg. 212:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downey DM, Monson B, Butler KL, Fortuna GR, Jr, Saxe JM, Dolan JP, Markert RJ, McCarthy MC. Does platelet administration affect mortality in elderly head-injured patients taking antiplatelet medications? Am Surg. 2009;75:1100–1103. doi: 10.1177/000313480907501115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivascu FA, Howells GA, Junn FS, Bair HA, Bendick PJ, Janczyk RJ. Predictors of mortality in trauma patients with intracranial hemorrhage on preinjury aspirin or clopidogrel. J Trauma. 2008;65:785–788. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181848caa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Washington CW, Schuerer DJ, Grubb RL., Jr Platelet transfusion: an unnecessary risk for mild traumatic brain injury patients on antiplatelet therapy. J Trauma. 2011;71:358–363. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318220ad7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Montori V, Akl EA, Djubegovic B, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence--study limitations (risk of bias) J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naidech AM, Bendok BR, Garg RK, Bernstein RA, Alberts MJ, Bleck TP, Batjer HH. Reduced platelet activity is associated with more intraventricular hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:684–688. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000351769.39990.16. discussion 688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naidech AM, Rosenberg NF, Bernstein RA, Batjer HH. Aspirin Use or Reduced Platelet Activity Predicts Craniotomy After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slichter SJ, Kaufman RM, Assmann SF, McCullough J, Triulzi DJ, Strauss RG, Gernsheimer TB, Ness PM, Brecher ME, Josephson CD, et al. Dose of prophylactic platelet transfusions and prevention of hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:600–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worster A, Bledsoe RD, Cleve P, Fernandes CM, Upadhye S, Eva K. Reassessing the methods of medical record review studies in emergency medicine research. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:448–451. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]