Abstract

Background Noninvasive ventilation is being increasingly used on preterm infants to reduce ventilator lung injury and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (SNIPPV) to prevent intubation in premature infants.

Methods Prospective observational study of SNIPPV use on preterm infants of less than 32 weeks' gestation. All patients were managed using a prospective protocol intended to reduce invasive mechanical ventilation (iMV) use. Previous respiratory status, as well as respiratory outcomes and possible secondary side effects were analyzed.

Results SNIPPV was used on 78 patients: electively to support extubation on 25 ventilator-dependent patients and as a rescue therapy after nasal continuous positive airway pressure failure on 53 patients. For 92% of patients in the elective group and 66% in the rescue group, iMV was avoided over the following 72 hours. No adverse effects were detected, and all patients were in a stable condition even if intubation was eventually needed.

Conclusions The application of SNIPPV in place of or to remove mechanical ventilation avoids intubation in 74.4% of preterm infants with respiratory failure. No adverse effects were detected.

Keywords: synchronized noninvasive ventilation, preterm infants, nCPAP failure, extubation failure

Recently, a less invasive respiratory management system for preterm infants has been increasingly used to decrease lung damage to immature infants due to the association between ventilator induced lung injury and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Animal studies reveal that as little as 2 hours of pressure limited ventilation induced an inflammatory response in the alveolar wash fluid. Premature lambs treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) have lower indicators of acute lung injury and better compliance.8 9

Nasal CPAP (nCPAP) improves oxygenation by stabilizing the lung volume in infants with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS).6 10 11 nCPAP as a primary mode of respiratory support has become a standard practice to avoid invasive mechanical ventilation (iMV) and to facilitate weaning from the ventilator.12 13 14 Although successful for a large proportion of infants, it is not always effective with failure rates ranging from 30 to 85%.6 10 11 15 This is mostly evident in more immature infants, who also have a higher susceptibility to lung injury and BPD development.16 17

Nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) is being increasingly used on preterm infants with respiratory failure.18 NIPPV delivers positive pressure cycles over the continuous distending pressure. The improved physiological effects of NIPPV over nCPAP include a higher mean airway pressure (MAP), a washout of the anatomical dead space in the upper airways, and possible stimulatory effects of intermittent cycling on the respiratory drive. Other beneficial effects are an increase in tidal volume and reduction in the effort required for breathing, which may depend on whether or not positive pressure cycles are synchronized with the patient's spontaneous respiratory effort, allowing the delivery of a positive pressure while the infant makes an effort, so that the glottis is open.

A recently published clinical report by the American Academy of Pediatrics concludes that synchronized NIPPV (SNIPPV) decreases the frequency of extubation failure but the evidence for non-SNIPPV or nasal bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) is inconclusive.19 The superiority of NIPPV or BiPAP (synchronized or nonsynchronized) over nCPAP in the management of infants with RDS is still not supported by published data. One reason for this absence of evidence could be attributed to the lack of approved devices able to provide an effective synchronization. The most studied system for synchronization during nasal ventilation in newborns is the Graseby capsule,20 21 22 but these ventilators are no longer in production. Recently, the neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA), which detects the neural activity of the diaphragm, seems to be a promising system but requires a significant financial investment, and clinical usefulness must be probed in an Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT).

Another studied synchronization system involves a flow sensor applied to a specifically designed neonatal nasal ventilator. The device's ability for synchronization has been tested on a neonatal model, suggesting that its performance is not affected by leaks.23 Benefits beyond nCPAP have been reported when applied to support extubation,24 25 after surfactant replacement,26 and during apnea spells.27

At our institution, nCPAP is the first line treatment for noninvasive support used on preterm infants. Since 2012, flow-SNIPPV use has been standardized as second-line treatment in lieu of MV in patients on whom nCPAP has already failed or to facilitate extubation in ventilator-dependent preterm infants.

To our knowledge, there is only one pilot study that has evaluated the effectiveness of NIPPV in the treatment of nCPAP failure, avoiding intubation in 74% of patients with no different outcome when compared with a conventional ventilation group.28

The aim of this study was to analyze the effectiveness of the use of synchronized noninvasive ventilation (flow-SNIPPV) in avoiding intubation when used as an alternative treatment to MV, when nCPAP fails, or for extubation on a select group of preterm infants who have a high risk of extubation failure.

Methods

Patients and Settings

This is a prospective observational study of SNIPPV use in preterm infants of less than 32 weeks' gestation born between 2012 and 2015.

Our unit's standard respiratory management protocol is summarized in the following.

All spontaneously breathing preterm infants of less than 32 weeks' gestation were supported with CPAP/positive-end expiratory pressure (PEEP) 6 cm H2O (Neopuff Infant T-Piece Resuscitator, Fisher&Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand) applied using a nasobuccal mask in the delivery room (DR). Initial FiO2 was 21 to 30% and then adjusted to keep saturation targets within standard limits.29 Nasobuccal CPAP was switched to nasal CPAP in the neonatal intensive care unit (Infant Flow Driver® device, Carefusion, San Diego, CA) using binasal short prongs for at least 2 hours with a MAP of at least 6 cm H2O and FiO2 to maintain preductal SpO2 between 90 and 95%.

Infants were routinely given intravenous caffeine citrate, with a loading dose of 20 mg/kg within the first 8 hours of life, followed by a daily maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg.

Exogenous surfactant was selectively administered if more than 30% of FiO2 was needed while on nCPAP support (nCPAP level > 6 cm H2O). An intubation, surfactant administration, and extubation method was applied up until October 2013 and less invasive surfactant administration using a thin catheter while on spontaneous nCPAP was applied thereafter. A second dose of surfactant was given if more than 40% of FiO2 was needed to maintain preductal SpO2 > 90%.

Intubation criteria are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Intubation criteria.

| FiO2 > 50% |

| Apnea episodes (>4/h or more than 1 needing IPP) |

| Respiratory acidosis pCO2 > 65 mm Hg and pH < 7.20 on arterial or capillary samples |

Abbreviation: IPP, intermittent positive pressure.

If intubation was needed, patients were ventilated in pressure support ventilation modality combined with volume guarantee, Dräger VN500 ventilator (Dräger Medical, Lübeck, Germany). A tidal volume of 4 to 6 mL/kg was adjusted, with a backup rate that ensures control of the patient's respiratory rate (RR) by triggering the ventilator, usually less than 35 to 40 inflations per minute.

Early extubation was promoted and supported with nCPAP after an evaluation of respiratory drive in patients in a clinically stable situation if the MAP was less than 10 cm H2O and oxygen requirement less than 35%.

Indications of Synchronized Nasal Intermittent Positive Pressure Ventilation Use

nCPAP failure: Preterm infants supported with nCPAP that meet intubation criteria (Table 1) if they are in a stable situation—systemic arterial pressure (SAP) > percentile 10 (P10) with preserved respiratory drive (no more than 6 apnea episodes per hour or more than two episodes requiring positive pressure ventilation (PPV).

-

Elective use for extubation:

Preterm infants in whom nCPAP extubation has previously failed in the previous 72 hours.

Prolonged MV (more than 15 days) with high respiratory parameters (MAP > 10 cm H2O; FiO2 > 35%).

Patients were closely monitored, and if they met intubation criteria after 2 hours of SNIPPV support or if clinical deterioration occurs before, iMV is initiated.

SNIPPV support was applied using a specifically designed neonatal nasal ventilator (Giulia, Ginevri Medical Technologies, Rome, Italy). Synchronization was obtained by means of a fixed orifice pneumotachograph, initially interposed between the prongs with the Y-piece being integrated into the nasal piece. The inspiratory flow was detected as a change in pressure across the resistance. The initial respiratory parameters were PEEP: 5 to 7 cm H2O; peak inspiratory pressure (PIP): 15–25 cm H2O; inspiratory time: 0.4 to 0.5 of a second; flow rate: 7 to 10 L/min; and RR: 30–40 breaths per minute. The level of trigger sensibility was set to the highest level to avoid auto-triggering.

Binasal–nasal short prongs were used. The size of the prongs was determined by the infant's weight. The largest possible prongs were used.

Inclusion criteria: Infants were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: gestational age of 230/7 to 316/7 weeks and indication of SNIPPV support using our standard respiratory management protocol.

Exclusion criteria: (1) hemodynamic instability SAP > percentile 10, (2) intubation because of anesthesia requirement, and (3) insufficient respiratory drive defined as more than six apnea episodes per hour or more than two episodes requiring PPV, or less than 30 spontaneous breaths per minute while on iMV. The reason for excluding infants with a lack of spontaneous respiratory effort was because nasal ventilation requires a minimum level of contribution from the patient in regard to ventilation to achieve synchronization to ensure the transmission of pressure to the distal airway.

Settings

Perinatal variables examined include gestational age, birth weight, antenatal steroid treatment, support applied at birth, days of life, surfactant replacement, and time on MV.

Indication for SNIPPV treatment was collected and the recorded variables were ventilation management, time on MV, time on nasal ventilation, moderate to severe BPD by physiological definition,30 duration of oxygen treatment, patent ductus arteriosus, retinopathy of prematurity, necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgical treatment, neurologic impairment (grade 3 or 4 intraventricular hemorrhage based on Papile's classification or persistent periventricular leukomalacia31), nasal trauma, and air leaks.

Success of SNIPPV is defined as requiring no invasive ventilation in the following 72 hours.

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed variables were described using means and standard deviations. Nonnormally distributed variables were expressed by medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Differences between categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. The t-test was used to compare means in normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare nonnormal distributed variables. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using the SPSS package version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) for Windows.

Results

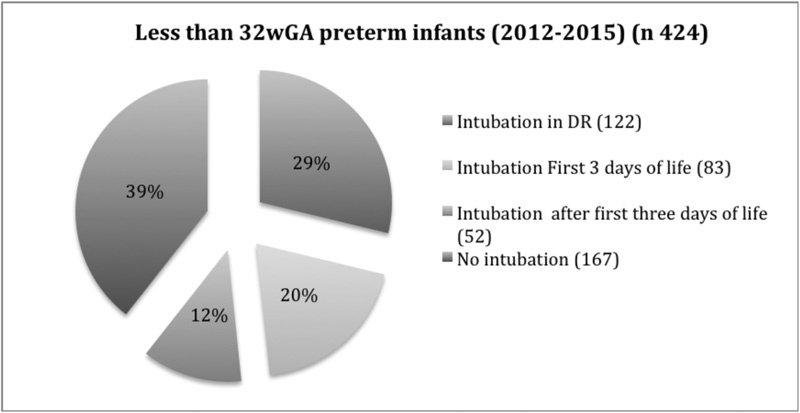

During the study period, a total of 424 preterm infants of less than 32 weeks' gestation were born at our institution. Of the 424 preterm infants, 122 (28.7%) were intubated in the DR, and the other 302 were initially managed with nCPAP, with 135 (44.7%) of them required iMV during hospitalization (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Invasive mechanical ventilation requirements during hospitalization.

A total of 78 patients born at less than 32 weeks' gestation were treated with SNIPPV during this period of time.

-

SNIPPV was electively used for extubation in 25 patients, with 23 (92%) not requiring reintubation over the following 3 days. Characteristics are given in Table 2.

Thirteen patients met the inclusion criteria because of prolonged MV and high respiratory assistance (median FiO2 and PMAP prior to extubation was 38% [IQR: 33–42.5] and 13% [IQR: 12–14] cm H2O, respectively). SNIPPV was applied in the other 12 patients because of nCPAP extubation failure in the previous 3 days. Median FiO2 in this group was 27.5% (IQR: 25–34) and mean airway pressure (MAP) was 13 cm H2O (IQR: 11–16). The time from previous extubation failure to SNIPPV extubation was 48 hours (IQR: 35–62.5).

-

SNIPPV was used on 53 patients as a rescue therapy for nCPAP failure and intubation was avoided in 35 patients (66%). Characteristics and results are given in Table 2.

Twenty-three patients had no previous exposure to iMV, and SNIPPV was successful in 16 patients (69.5%). Success rates were higher when applied after the first 3 days of life (84.6%; n = 13) compared with when used within the first 3 days (50%; n = 10). All of them were previously treated with surfactant.

SNIPPV was used on the other 30 infants previously exposed to iMV that met the nCPAP failure inclusion criteria after a variable period of extubation. Reintubation was avoided in 19 patients (63.3%).

Table 2. Results.

| Elective use (n = 25) | nCPAP failure (n = 53) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA (wk) (median; IQR) | 25.7; 25.0–26.6 | 27.5; 26.1–28.7 | 0.001 | |||

| Weight at birth (g) (median; IQR) | 680; 500–860 | 930; 745–1,150 | 0.002 | |||

| Days of life (median; IQR) | 39; 17–60 | 11; 5.5–24 | 0.022 | |||

| Prenatal corticosteroids, n (%) | 19 (76) | 45 (84.9) | 0.517 | |||

| Rate of intubation at delivery, n (%) | 18 (72) | 23 (43.4) | 0.061 | |||

| Surfactant, n (%) | 22 (88) | 46 (86.8) | 0.356 | |||

| Days of MV prior to SNIPPV use (median; IQR) | 60; 28–192 | 5; 0–72 | <0.001 | |||

| Duration (h) of SNIPPV support (median; IQR) | 96; 48–132 | 48; 10–84 | 0.033 | |||

| Air leaks, n (%) | 1 (4)a | 4 (7.5)b | 0.551 | |||

| Nasal injury, n (%) | 0 | 1 (1.9)c | 0.489 | |||

| Pathologic cranial ultrasound,d n (%) | 1 (4)1 | 4 (7.5) | 0.551 | |||

| Successe | 23(92) | 35 (66) | 0.014 | |||

| Previous nCPAP extubation failure (n = 12) | Ventilator-dependent patients (n = 13) | Apnea (n = 23) | Hypoxemia (n = 15) | Respiratory acidosis (n = 15) | ||

| 11 (91.7) | 12 (92.3) | 15 (62.5) | 9 (60) | 11 (73.3) | 0.081 | |

Abbreviations: GA, gestational age; IQR, interquartile range; MV, mechanical ventilation; nCPAP, nasal continuous distended pressure; SNIPPV, synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation.

Previous to SNIPPV use.

Previous to SNIPPV use.

Resolved with topical care, no iMV was needed.

Intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or 4 based on Papile's classification or persistent periventricular leukomalacia (more than 15 days).

No iMV in the next 72 h.

Of the 83 patients intubated within the first 3 days of life during this period (Fig. 1), 8 met the inclusion criteria for SNIPPV use, but it could not be used on 3 of them because of the unavailability of the device. The other five patients were intubated after a trial of SNIPPV in a median time of 6 hours (1.5–12). Five patients met inclusion criteria in the first 3 days of life after being successfully treated with SNIPPV.

Fifty-two infants met the inclusion criteria for SNIPPV use after the first 3 days of life because of nCPAP failure with application on 43 infants, while the remaining 9 infants were not given SNIPPV as the device was not available at the time it was required. The success rate for this group was 69.7% (30).

All patients could be properly managed with SNIPPV support in a stable hemodynamic situation.

When intubation was finally needed, the median time was 5.5 hours (2.2–12). No significant differences have been found in SNIPPV patient successes versus failures except for the more frequent nCPAP failure indication (Table 3).

Table 3. Results.

| SNIPPV success (n = 58) | SNIPPV failure (n = 20) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA (median; IQR) | 26.7; 25.9–28.2 | 26.9,25.7–27.9 | 0.506 |

| Weight at birth (median; IQR) | 885; 667–885 | 765; 550–887 | 0.175 |

| Days of life (median; IQR) | 16; 8.0–48.2 | 18.5; 1.7–29.5 | 0.357 |

| Prenatal corticosteroids, n(%) | 49 (84.5) | 15 (75) | 0.635 |

| Rate of intubation at delivery, n(%) | 28 (48.3) | 13 (65) | 0.326 |

| Surfactant, n(%) | 49 (84.4) | 95% (19) | 0.279 |

| Days on MV prior to SNIPPV use (median; IQR) | 7; 1.0–24.0 | 7; 1.0–30.0 | 0.917 |

| nCPAP failure indication, n (%) | 35 (60.3) | 18 (90) | 0.014 |

| Time on SNIPPV support (h) (median; IQR) | 72; 48.0–120.0 | 5.5; 2.2–12.0 | <0.01 |

| Death or BPD (II–III), n (%) | 28 (48.3) | 13 (65) | 0.497 |

| Pathologic cranial ultrasound,a n (%) | 10(17.2) | 4(20) | 0.782 |

| NEC,b n (%) | 7(12.1) | 5(26.3) | 0.139 |

| ROP,c n (%) | 11(19.3) | 3(16.3) | 0.210 |

| PDA,d n (%) | 17 (29.3) | 8(42.1) | 0.310 |

| Oxygen treatment (d) Median (IQR) | 62 (45–95) | 65 (59.7–202.5) | 0.127 |

| Oxygen at discharge, n (%) | 14 (24.1) | 8 (42.1) | 0.149 |

| Death, n (%) | 5 (8.6) | 3 (15.8) | 0.497 |

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; GA, gestational age; IQR, interquartile range; MV, mechanical ventilation; nCPAP, nasal continuous positive airway pressure; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; SNIPPV, synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation.

Intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3 or 4 based on Papile's classification or persistent periventricular leukomalacia (more than 15 days).

Requiring surgery.

Requiring laser therapy.

Requiring surgical or percutaneous closure.

The rate of infants of less than 32 weeks' gestational age who are managed without intubation during hospitalization has increased during the implementation of the actual SNIPPV use protocol from 41.9% in 2012 to 45.3% in 2015, even when the proportion of infants of less than 26 weeks' gestation has increased from 15.4% in 2012 to 20% in 2015 (p = 0.329). The rate of intubation in patients managed with noninvasive support from birth decreased from 34.4 to 17.9% (p = 0.048). Survival free of mild and moderate BPD has increased from 62.4% in 2012 to 66.3% (0.554) in 2015, with trends showing a reduction in the combined effect of death and severe BPD (rates from 23 to 18.3%; p = 0.776) (Table 4).

Table 4. Outcomes in infants of less than 32 weeks' GA since implementation of SNIPPV use protocol.

| 2012 (n = 117) | 2015 (n = 95) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA (wk) | 28.9 (27.1–31) | 28.0 (26.1–29.7)) | 0.069 |

| Weight (g) | 1,140 (880–1,502) | 1,000 (750–1,350) | 0.003 |

| Intubation first 2 h | 29 (24.8) | 35 (36.8) | 0.062 |

| Crib score | 1 (0–4) | 3 (1–7) | 0.005 |

| Time on MV (h), mean (SD) | 198 (551.2) | 214 (458.9) | 0.580 |

| SNIPPV use | 1 (0,9) | 26 (27.7) | <0.001 |

| No MV during hospitalization | 39 (41.9) | 43 (45.3) | 0.453 |

| Noninvasive failurea | 39 (33.4) | 17 (17.8) | 0.022 |

| Surfactant treatment | 62 (53) | 60 (63.2) | 0.136 |

| HFOV on day 3 | 15 (12.8) | 23 (24.2) | 0.045 |

| PDA | 38 (33.6) | 37 (39.2) | 0.393 |

| Air leaks | 9 (7.7) | 9 (9.5) | 0.644 |

| Nosocomial sepsis | 76 (65) | 42 (44.2) | 0.008 |

| Pathologic cranial ultrasound | 13 (11.1) | 18 (18.9) | 0.108 |

| SF-BPD global | 73 (62.4) | 63 (66.3) | 0.359 |

| SF-BPD < 26 wk | 11.1% | 15.8% | 0.677 |

| SF-BPD: 26–29 wk | 48.8% | 70% | 0.05 |

| SF-BPD > 29 wk | 89.3% | 88.9% | 0.952 |

| Death or severe BPD | 27 (23) | 18 (18.3) | 0.776 |

| Mortality | 18 (15.4) | 14 (14.7) | 0.320 |

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; GA, gestational age; HFOV, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; MV, mechanical ventilation; SNIPPV, synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; SD, standard deviation; SF, survival-free.

In infants managed at birth with noninvasive support.

Note: Data expressed in n (%) or median (IQR).

Discussion

SNIPPV applied instead of or for the removal of MV avoids intubation in 74.4% of preterm infants with respiratory failure. No adverse effects have been observed even in those patients who eventually required iMV.

The success rates of SNIPPV used for ventilator removal is similar to previously reported rated for NIPPV (89.2% vs. 92%)32, even when flow-SNIPPV was applied during this study to a selected high risk group of patients in which nCPAP extubation had previously failed or in patients with the need of high respiratory assistance. In contrast, in previously published trials, NIPPV extubation was performed from low levels of respiratory support reflecting less severe pulmonary affection (usually less than 35% of the oxygen requirement).32

Nesbitt et al reported a 66.6% success rate of noninvasive ventilation support applied to unplanned extubations.33 When comparing the baseline characteristics of the 30 patients included in the Nesbitt et al study with the 25 patients included in this study, there were more mature infants (median gestational age: 27 + 6 vs. 25 + 6), with greater birth weights (median: 934 vs. 680 grams) and lower previous FiO2 requirements (21 vs. 40.8%). The success rate of SNIPPV in preventing reintubations is greatest in our highest risk population (92%), showing potential added benefits of program extubations and prompt administration of SNIPPV support after endotracheal tube removal rather than delayed use after an accidental extubation. The success rate is also significantly lower in this study when SNIPPV is used after the intubation criteria has been met when compared with when it is administered electively. One explanation could be that SNIPPV can support ventilation in this high-risk group when they are in the “best condition” possible. Once deterioration has already begun, SNIPPV is not always able to resolve the situation. This is especially evident during the first 3 days of life in which success rates were lower even when all these patients were previously treated with exogenous surfactant administration.

This observation is consistent with the study of Badiee et al24 in which risk factors for needing intubation after applying of NIPPV for nCPAP failure also included a lower postnatal age at entrance to study (median 1 day in failure group) and a requirement of more frequent doses of surfactant. It seems that for patients in their first days of life who have already met intubation criteria due to RDS despite exogenous surfactant replacement, SNIPPV is less effective and in many cases cannot even be tried because of a possible abrupt impairment of the respiratory drive (85.3% met exclusion criteria for SNIPPV use). It is possible that earlier SNIPPV support, if there is no clinical improvement after surfactant treatment without waiting to meet intubation criteria, could decrease the requirement of iMV. In a pilot study recently published by our group, a lack in FiO2 reduction after surfactant treatment was associated with the need for iMV,34 so it is likely that this group of patients will benefit from switching from nCPAP to SNIPPV. The reported intubation rate when this device is used electively after surfactant administration was 6.1% in contrast to a 35.5% failure rate in the group of nCPAP.26

The success rate of NIPPV used for nCPAP failure is also higher in the pilot study of Badiee et al28: 74% (n = 27) versus 66% (n = 53) but the included patient's greater maturity (mean gestational age: 28.7 vs. 27.4 in this study), larger weight (mean: 1,159 vs. 930 grams), and less surfactant requirement (48 vs. 86.8%) should be taken into account making these two populations incomparable.

Apnea spells are one of the main reasons for nCPAP failure (Table 2), and even when infants with severe apnea were excluded from SNIPPV use in this study, quite a high proportion, 37.5% of infants that met intubation criteria due to apnea spells finally required intubation. Some reports found no pressure transmission to the chest wall or an increase in tidal volume in apnea spells.35 36 Nasal ventilation requires a quite preserved respiratory drive to ensure pressure transmission to the distal airway. Synchronized delivery of NIPPV cycles to the infant's inspiration is believed to increase the efficacy of NIPPV because the pressure is dispensed when the glottis is open, minimizing transmission through the esophagus to the stomach. This allows an increase in tidal volume, a decrease in work of breathing (WOB)37 38 and a reduction to the risk of gastrointestinal side effects. Conversely, asynchronous breaths can induce laryngeal closure and inhibit inspiration,39 increase abdominal distension and WOB.40 41

The benefits of synchronization in noninvasive ventilation has been probed in clinical trials when used for the prevention of extubation failure,12 32 37 but there is still not enough evidence of superiority of noninvasive ventilation, synchronized or otherwise, over nCPAP when applied for RDS management in preterm infants as is concluded in the recently published clinical report of American Academy of Pediatrics.19 Most of the studies analyzed in this report used non-SNIPPV. The main problem may be the lack of devices that are able to synchronize and approved for use on newborns for noninvasive ventilation. The Graseby capsule is not available in the United States for SNIPPV, and the infant flow SiPAP system driver is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The usefulness of the NAVA system, even though it seems promising, has still to be proven in RCTs. Synchronized ventilator generated NIPPV is the only NIPPV mode consistently shown to provide a benefit over nCPAP.32

At our institution, flow SNIPPV has been applied since 2004, provided by a neonatal nasal ventilator (Giulia®).

The synchronization effectiveness of this device has been proven in a simulated neonatal model23 highlighting that the Giulia flow sensor is capable of detecting very small “spontaneous” inspiratory volumes (0.021 ± 0.02 mL) and flows (3 mL/second) and that its performance is not affected by the amount of leakage. The steady component of flow generated by the continuous variable leaks is quantified and deducted, while the fast variations of flow due to spontaneous breathing are used to trigger the ventilator. The dead space of the transducer is remarkably reduced (1 mL) as it is enclosed in the joint between the nasal cannula and the Y-piece.

Clinical trials using this device have shown its efficacy to prevent extubation failure when compared with nCPAP (10 vs. 30%),25 to decrease intubation rates when used in RDS after surfactant administration (6.1 vs. 35.5%),26 and to reduce the apnea episodes compared with nCPAP and non-SNIPPV.27

In our study, SNIPPV applied instead of invasive ventilation in preterm infants with respiratory failure is safe and effective in 66% of cases. Success rates for elective use are higher (92%), and even though we are unable to confirm how many of these patients will be reintubated without SNIPPV support because of the lack of a control group, all these infants were classified as needing high respiratory assistance or nCPAP extubation had recently failed so, in clinical practice, they would not have been extubated otherwise.

The simplicity and wide availability of nCPAP systems make it the most suitable first-line noninvasive respiratory treatment for preterm infants, but early predictors of nCPAP failure and safe extubation parameters should be established to provide a precocious SNIPPV support to reduce iMV exposure.

Since the implementation of SNIPPV use in the respiratory management of preterm infants, we have found an increase in the survival rate of BPD with a decrease in the rates of death or severity of BPD, but it should be noted that there were also other modifications in respiratory management during this period, including the administration of surfactant using less invasive techniques and an increased use of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation for protective lung ventilation.

An RCT is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of synchronized nasal ventilation in reducing intubation and BPD rates in this select group of preterm infants in which nasal CPAP is not sufficient.

Limitations of the Study

This is a pragmatic observational study with limitations, including the small sample size and lack of randomization, but reflects the utility and safety of the technique in current clinical practices.

Conclusions

SNIPPV applied instead of or for the removal of MV avoids intubation in 74.4% of preterm infants with respiratory failure. No adverse effects were detected even if intubation was finally needed. Effectiveness is lower when used for nCPAP failure when intubation criteria were achieved. SNIPPV support criteria should be specifically defined to ensure early SNIPPV application, mostly during the first days of life. An RCT is needed to analyze the effectiveness of SNIPPV over nCPAP in this select group of preterm infants, evaluating the long-term consequences of SNIPPV use in pulmonary function.

Contribution

Cristina Ramos-Navarro has participated in the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript and has approved the manuscript as submitted. Manuel Sanchez-Luna has participated in the concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revising the manuscript and has approved the manuscript as submitted. Ester Sanz-Lopez has contributed to study design, data collection, and revising the manuscript and has approved the manuscript as submitted. Elena Maderuelo-Rodriguez has contributed to the concept and revising the manuscript and has approved the manuscript as submitted. Elena Zamora-Flores has contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and revising the manuscript and has approved the manuscript as submitted.

Conflict of Interest All authors declare no conflict of interest and there is not financial support. Clinical Trials Registration Number NCT02628821.

Note

Approval for this study was obtained from the Local Ethics Committee.

References

- 1.Wright C J, Kirpalani H. Targeting inflammation to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia: can new insights be translated into therapies? Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):111–126. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Kaam A. Lung-protective ventilation in neonatology. Neonatology. 2011;99(4):338–341. doi: 10.1159/000326843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillman N H, Moss T J, Kallapur S G. et al. Brief, large tidal volume ventilation initiates lung injury and a systemic response in fetal sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):575–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-051OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank J A, Parsons P E, Matthay M A. Pathogenetic significance of biological markers of ventilator-associated lung injury in experimental and clinical studies. Chest. 2006;130(6):1906–1914. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gharib S A, Liles W C, Klaff L S, Altemeier W A. Noninjurious mechanical ventilation activates a proinflammatory transcriptional program in the lung. Physiol Genomics. 2009;37(3):239–248. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morley C J Davis P G Doyle L W Brion L P Hascoet J M Carlin J B; COIN Trial Investigators. Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants N Engl J Med 20083587700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bose C L, Laughon M M, Allred E N. et al. Systemic inflammation associated with mechanical ventilation among extremely preterm infants. Cytokine. 2013;61(1):315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jobe A H, Kramer B W, Moss T J, Newnham J P, Ikegami M. Decreased indicators of lung injury with continuous positive expiratory pressure in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res. 2002;52(3):387–392. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200209000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillman N H, Nitsos I, Berry C, Pillow J J, Kallapur S G, Jobe A H. Positive end-expiratory pressure and surfactant decrease lung injury during initiation of ventilation in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301(5):L712–L720. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00157.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finer N N, Carlo W A, Walsh M C. et al. Early CPAP versus surfactant in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1970–1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn M S, Kaempf J, de Klerk A. et al. Randomized trial comparing 3 approaches to the initial respiratory management of preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1069–e1076. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meneses J, Bhandari V, Alves J G, Herrmann D. Noninvasive ventilation for respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):300–307. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee on Fetus and Newborn; American Academy of Pediatrics . Respiratory support in preterm infants at birth. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):171–174. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweet D G, Carnielli V, Greisen G. et al. European consensus guidelines on the management of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants—2013 update. Neonatology. 2013;103(4):353–368. doi: 10.1159/000349928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ammari A, Suri M, Milisavljevic V. et al. Variables associated with the early failure of nasal CPAP in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2005;147(3):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dargaville P A, Aiyappan A, De Paoli A G. et al. Continuous positive airway pressure failure in preterm infants: incidence, predictors and consequences. Neonatology. 2013;104(1):8–14. doi: 10.1159/000346460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jobe A H, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoll B J, Hansen N I, Bell E F. et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings J J Polin R A; Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics. Noninvasive respiratory support Pediatrics 201613711–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrington K J, Bull D, Finer N N. Randomized trial of nasal synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation compared with continuous positive airway pressure after extubation of very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):638–641. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedlich P Lecart C Posen R Ramicone E Chan L Ramanathan R A randomized trial of nasopharyngeal-synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation versus nasopharyngeal continuous positive airway pressure in very low birth weight infants after extubation J Perinatol 199919(6 Pt 1):413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalaf M N, Brodsky N, Hurley J, Bhandari V. A prospective randomized, controlled trial comparing synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure as modes of extubation. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):13–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moretti C PP Gizzi C et al. Flow-synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation in the preterm infant: development of a project J Pediatr Neonatal Individualized Med 20132e020211. Doi: 10.7363/020211 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moretti C, Gizzi C, Papoff P. et al. Comparing the effects of nasal synchronized intermittent positive pressure ventilation (nSIPPV) and nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) after extubation in very low birth weight infants. Early Hum Dev. 1999;56(2–3):167–177. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(99)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moretti C, Giannini L, Fassi C, Gizzi C, Papoff P, Colarizi P. Nasal flow-synchronized intermittent positive pressure ventilation to facilitate weaning in very low-birthweight infants: unmasked randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Int. 2008;50(1):85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gizzi C, Papoff P, Giordano I. et al. Flow-synchronized nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation for infants <32 weeks' gestation with respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:301818. doi: 10.1155/2012/301818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gizzi C, Montecchia F, Panetta V. et al. Is synchronised NIPPV more effective than NIPPV and NCPAP in treating apnoea of prematurity (AOP)? A randomised cross-over trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100(1):F17–F23. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Badiee Z, Nekooie B, Mohammadizadeh M. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation or conventional mechanical ventilation for neonatal continuous positive airway pressure failure. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(8):1045–1053. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kattwinkel J, Perlman J M, Aziz K. et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):e1400–e1413. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2972E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan R M. A new look at bronchopulmonary dysplasia classification. J Perinatol. 2006;26(4):207–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papile L A, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92(4):529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemyre B, Davis P G, De Paoli A G, Kirpalani H. Nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) for preterm neonates after extubation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9(9):CD003212. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003212.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesbitt G, Guy K J, König K. Unplanned extubation and subsequent trial of noninvasive ventilation in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(11):1059–1063. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1548536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos-Navarro C, Sánchez-Luna M, Zeballos-Sarrato S, González-Pacheco N. Less invasive beractant administration in preterm infants: a pilot study. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2016;71(3):128–134. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2016(03)02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan C A, Finer N N, Peters K L. Nasal intermittent positive-pressure ventilation offers no advantages over nasal continuous positive airway pressure in apnea of prematurity. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143(10):1196–1198. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150220094026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owen L S, Morley C J, Dawson J A, Davis P G. Effects of non-synchronised nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation on spontaneous breathing in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2011;96(6):F422–F428. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.205195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang L, Mendler M R, Waitz M, Schmid M, Hassan M A, Hummler H D. Effects of synchronization during noninvasive intermittent mandatory ventilation in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome immediately after extubation. Neonatology. 2015;108(2):108–114. doi: 10.1159/000431074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang H Y, Claure N, D'ugard C, Torres J, Nwajei P, Bancalari E. Effects of synchronization during nasal ventilation in clinically stable preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2011;69(1):84–89. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181ff6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Praud J P, Samson N, Moreau-Bussière F. Laryngeal function and nasal ventilatory support in the neonatal period. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006;7 01:S180–S182. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2006.04.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutchison A A, Bignall S. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in the preterm neonate: reducing endotrauma and the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(1):F64–F68. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.103770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moreau-Bussière F, Samson N, St-Hilaire M. et al. Laryngeal response to nasal ventilation in nonsedated newborn lambs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102(6):2149–2157. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00891.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]