Abstract

Study Objective

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods are the most effective form of reversible contraception but are underutilized by adolescents. The purpose of this study is to identify the context-specific barriers to providing adolescents with LARC that are experienced by pediatricians, family medicine physicians, and advanced practice nurses (APNs).

Design/Settings/Participants

Pediatricians, family medicine providers and APN's (n=16) who care for adolescents participated in semi-structured qualitative interviews. Interview data were analyzed through a modified grounded theory approach.

Main Outcome Measures

Pediatricians, family medicine physicians and APNs' self-reported attitudes and practices regarding LARC provision to adolescents.

Results

Provider confidence in LARC, patient-centered counseling on LARC and instrumental supports for LARC all work interdependently either in support of or in opposition to provision of LARC to adolescents. Low provider confidence in LARC for adolescents was characterized by confusion about LARC eligibility criteria and perceptions of LARC insertion as traumatic for adolescents. Patient-centered counseling on LARC required providers' ability to elicit patient priorities, highlight the advantages of LARC over other methods and address patients' concerns about these methods. Instrumental supports for LARC included provider training on LARC, access to and financial support for LARC devices and opportunity to practice LARC insertion and counseling skills.

Conclusions

While none of the identified essential components of LARC provision to adolescents exist in isolation, instrumental supports like provider training on LARC and access to LARC devices have the most fundamental impact on the other components and on providers' attitudes and practices regarding LARC for adolescents.

Keywords: Long-acting reversible contraception, Adolescents, Unintended pregnancy, Contraception, Teen pregnancy, Qualitative

Introduction

Eighty-two percent of adolescent pregnancies in the U.S. are classified as unplanned1 and contraceptive methods with high typical use failure rates (up to 10% to 15%) continue to be the most commonly used by adolescents2,3. Hence, there is an “unmet need” for contraceptive methods that are acceptable, reliable and highly effective for adolescents4. Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, which include intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants, are the most effective methods of reversible contraception with a failure rate of <1%. LARC methods are recommended as first-line contraceptive options for all women, including adolescents, by The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Institute of Medicine4-6. However, only 4.5% of adolescents aged 15 – 19 who use contraception use LARC7. Reasons for adolescents' low use of LARC compared to other, less effective methods include: perceptions that they are not eligible for LARC unless they have given birth, lack of knowledge about LARC, fear of these methods, dislike of LARC side effects and preference for other methods8-11.

Healthcare providers may be instrumental in increasing adolescents' knowledge of LARC while addressing their fears about these methods. However, since interaction with a provider is required for uptake of these methods, providers themselves may also act as a barrier to LARC provision. To date, much of the research exploring provider barriers to LARC provision is 1) limited to studies of only obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs) or family physicians12-15, 2) focused on IUDs, to the exclusion of implants10,16,17 and 3) not specifically focused on adolescents12,13, for whom providers may experience different barriers to providing LARC than other patient age groups. Yet we know from this literature that provider barriers to LARC provision include infrequent counseling on LARC18, restrictive misconceptions about patient eligibility for LARC, confusion about risk of pelvic inflammatory disease associated with LARC, and lack of training on LARC insertion10,12,13,15-17.

This study team previously conducted a quantitative study of LARC knowledge, attitudes and practices among family medicine physicians, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, certified nurse midwifes (CNMs), and advance practice nurses (APNs)19. Two important findings from that investigation prompted the current qualitative study. First, compared to CNMs and OB/GYNs, family medicine physicians, pediatricians and APNs demonstrated less LARC knowledge, had fewer LARC-supportive attitudes and were less likely to include counseling about LARC at all or most adolescent patient visits. Second, “perceived patient disinterest” was the most frequently cited barrier to adolescent LARC provision across providers of all types, yet the meaning of “perceived patient disinterest” remains unclear. In addition to actual patient preferences, “perceived patient disinterest” in LARC methods may also be a function of providers' counseling practices and ability to place LARC devices. Qualitative inquiry is suited to uncover the subjective perceptions and practices that inform providers' attitudes towards LARC and how those attitudes impact counseling on LARC.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with APNs, family physicians and pediatricians about their thoughts and experiences with counseling on and providing LARC methods to adolescents. To explore the provider-based barriers to LARC that go beyond providers' perception that adolescents are disinterested in LARC, we organized our analysis around a question: “If an adolescent is eligible for LARC and lacks knowledge about these methods but is open to learning about them, what provider-based supports and competencies are required to result in successful provision of LARC to that adolescent?”

Materials and Methods

Sample and Recruitment

The University of Illinois-Chicago Institutional Review Board approved this study and all participants were recruited and enrolled between May and September of 2014. Eligibility criteria included being a family physician, pediatrician or APN, seeing at least 3 adolescent patients on average per week and prescribing contraception to those patients. Purposive sampling was conducted through a variety of recruitment strategies, including an emailed invitation to participate and in-person recruitment at a federally qualified health center. Study participants in the final sample (n=16) included family physicians (n=5), pediatricians (n=5) and APNs (n=6) practicing in large academic and community health centers, federally qualified health centers, school based health centers, and private practices in the Chicago area.

Data Collection

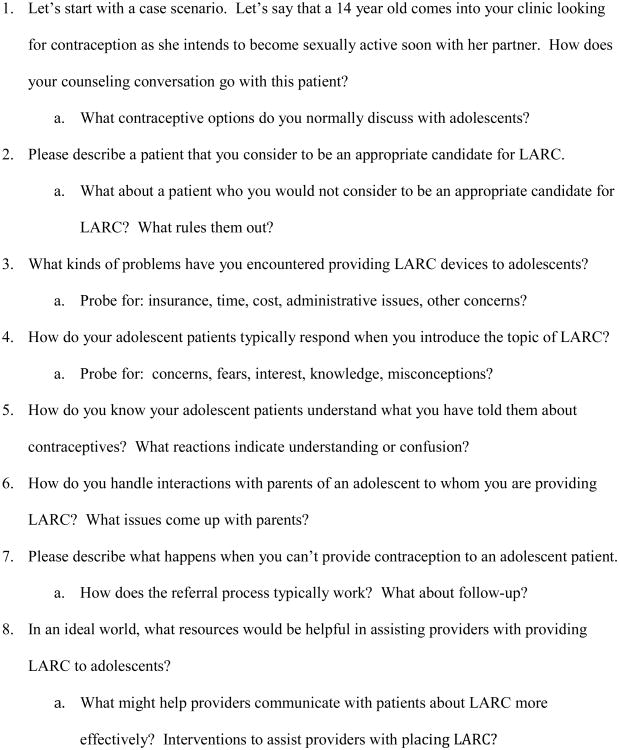

Study participation consisted of one in-person semi-structured interview with a member of the study staff who is experienced in qualitative methods and is a Registered Nurse, but did not have a relationship with the study participants prior or subsequent to their participation. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. All interviews were audio-recorded with the permission of participants (range: 23–47 minutes; mean length: 37 minutes). Upon completion of the interview, participants were compensated with $30.00 gift cards for their time. The interview instrument covered a variety of topics pertaining to LARC and adolescent contraceptive use (Figure 1). Interviews were transcribed and uploaded into Dedoose, a qualitative data management program, to facilitate analysis.

Figure 1. Abbreviated Interview Guide.

Data Analysis

Data analysis consisted of a content analysis in which the interview guide and codebook were informed by a priori as well as emergent ideas about providers' experiences with and perceptions of providing adolescents with LARC. Analytic techniques of coding, memo-writing and development of conceptual models were used to identify themes and relationships indicated by the data.

The codebook was modified iteratively during the initial stages of analysis and two study team members independently coded the data according to final codebook definitions. Throughout analysis, coders constructed analytic memos. As “the intermediate step between coding and the first draft of the completed analysis”20, these memos were essential to the refinement of codes and the development of conceptual models.

The Cohen's Kappa test of inter-rater reliability of code application was performed on all codes within a subset of three coded transcripts. This resulted in a 93.61% level of agreement, which falls within the range of “almost perfect” reliability between coders21.

Results

Provider Training and Current Provision of LARC

Our sample was diverse in terms of years since providers had completed training, (mean: 15.3 years) as well as providers' history of training on LARC and current practices providing LARC (Table 1). Four providers had been trained on both implants and IUD's and could regularly provide both LARC methods at the time of the interview. Five providers had been trained on both LARC methods but were not always able to provide one or both at the time of the interview because 1) they felt they needed additional supervision when placing the devices but did not have access to that oversight, 2) they were unable to obtain the devices for their clinical settings due to financial constraints, or 3) they were waiting for privileges to provide LARC in their clinic. Four providers had been trained on the IUD but not the implant, only one of whom provided the IUD at the time of the interview. Three providers had never been trained on either LARC method and could not provide either method at the time of the interview.

Table 1. Provider Training and Current Practices for LARC.

| Provider | Trained on Implant? | Trained on IUD? | Provides Implant? | Provides IUD? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete LARC Training and Provision | ||||

| Family medicine 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Family medicine 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| APN 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pediatrician 5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Complete LARC Training and Inconsistent Provision | ||||

| Family medicine 1 | Yes | Yes | Sometimes – not always able to get the device, refers externally in that case | Yes |

| Family medicine 4 | Yes | Yes | Sometimes – not always able due to “financial, insurance, clinic budget” reasons | Sometimes – not always able due to “financial, insurance, clinic budget” reasons |

| APN 4 | Yes | Yes | No – has been trained but is awaiting privileges, but can refer internally in the meantime | Yes |

| APN 6 | Yes | Yes | No – not comfortable doing it without oversight and no one available for this role | Yes |

| Pediatrician 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sometimes – not comfortable doing it without oversight and person inconsistently available for this role |

| Partially Complete LARC Training and Inconsistent Provision | ||||

| Family medicine 2 | No | Yes | No – can refer internally | Yes |

| APN 1 | No | Yes | No | No – is not able to access devices |

| APN 5 | No | Yes – has never done one since training | No | No – can refer internally |

| Pediatrician 1 | No | Yes – was trained “years ago” | No | No |

| No LARC Training or Provision | ||||

| APN 3 | No | No | No | No |

| Pediatrician 2 | No | No | No | No |

| Pediatrician 3 | No | No | No | No |

The Essential Components of LARC provision

We identified three essential components of providing LARC to adolescents who are eligible for LARC and open to learning about these methods: provider confidence in LARC, patient-centered counseling, and instrumental supports for LARC insertion (Table 2). Across all providers and within any one provider's experience, presence of the essential components and subcomponents varied. Providers whose experiences and thoughts reflected more of the essential components were more likely to 1) be supportive of LARC adoption among adolescents, 2) provide LARC regularly and 3) express confidence in their LARC knowledge. Absences of the essential components can be conceptualized as barriers to LARC provision.

Table 2. Essential components and subcomponents for adolescent LARC provision.

| Essential Component | Critical Question | Subcomponents |

|---|---|---|

| Provider Confidence in LARC | Does the provider have attitudes and knowledge that support LARC provision? | Knowledge about LARC eligibility criteria and side effect profile |

| Belief that LARC is a good method for adolescents | ||

| Belief that adolescents can emotionally and physically tolerate LARC insertion | ||

| Belief that adolescents can make healthy decisions for themselves about contraception and sex | ||

| Patient-centered Counseling | Can patients and providers work together to determine if LARC are compatible with patient priorities and concerns? | Provider elicits and respects patient priorities |

| Provider is dexterous at highlighting relative advantages of LARC over other methods | ||

| Provider is able to address patient concerns about LARC | ||

| Instrumental Supports for LARC insertion | If a provider and patient are both ready for LARC, is the clinic environment supportive of LARC provision? | Provider has been trained, provided with oversight and has had opportunity to practice insertion |

| LARC insertion can be completed at patient's regular clinic | ||

| LARC insertion procedure is financially covered and insertion materials are available at patient's regular clinic |

Essential Component 1: Provider Confidence in LARC

Consistent with prior research, providers indicated that one reason that they do not counsel on or provide adolescent patients with LARC is that they perceive adolescents to be disinterested in LARC and prefer other methods. Compounding this perception is providers' lack of confidence in their own abilities to counter adolescents' fears and misconceptions about LARC. Incorrect information, confusion about eligibility, and low confidence in their LARC knowledge influenced how many providers' determined if a patient is eligible for LARC and affected their counseling as well. When providers acknowledged their uncertainty about how to determine a patient's fitness for LARC, they indicated (often apologetically) that their knowledge may be based on outdated information or that they were confused about specific eligibility criteria. A patient's relationship status, number of sexual partners, and history of STI were deemed potential risks and contraindications for LARC use, but providers were often unsure of how important these characteristics actually were to LARC eligibility.

To varying degrees, all providers expressed concern that LARC insertion can be physically traumatic or emotionally distressing for adolescent patients. However, these age-based concerns about LARC insertion were rendered irrelevant if the patient had previously given birth.

“It's interesting. If they're 16 and they've already had a baby, I have no trouble with it. But when they've not had a child before…[LARC use for an adolescent beyond insertion] is not the issue, it's more insertion.”

– APN 3

Providers who had experience providing LARC methods to nulliparous patients described how as they performed these insertions more frequently, their confidence in nulliparous patients' ability to tolerate the procedure and their own confidence in performing it increased.

“I know I was intimidated, as far as learning to place IUD's in nulliparous patients. I just thought it was going to be very, very difficult, so I used to refer patients all the time…Now I'm taking that responsibility on myself and kind of seeing that it's not as big a deal as I had built it to be in my mind.”

– APN 2

While some level of concern about trauma of insertion was salient among all providers, it was not mirrored by ambivalence about LARC as good methods for adolescents beyond insertion.

“Once it's in, I think they're going to like it.”

– APN 4

A few providers had experience with adolescent patients wanting early removal of a LARC method. They felt that expanded support for providers on helping adolescents anticipate and manage undesirable side effects would help counter this trend.

“A lot of adolescents like to get them taken out earlier than usual, and so I think not only having the training or the support for the LARC and encouraging people to do LARC, but having that support afterwards so that when a teenager comes and says, “I'm bleeding for three months straight,” and you're saying, “Oh, we can take care of that,” as opposed to, “I want this removed, this is not working for me,” I think more education for providers and adolescents will help with that.

– Family medicine provider 3

While generally enthusiastic about providing adolescents with contraception, providers were hesitant about their ability to counsel effectively on LARC methods, specifically. Providers explained their lack of confidence in counseling on LARC in terms of their uncertainty about eligibility and side effects of these methods, as well as their lack of experience providing LARC compared to shorter-acting, less effective methods.

Essential Component 2: Patient-centered Counseling

All providers indicated that effective counseling requires dexterity with identifying patient priorities, confronting myths and fears about LARC, and highlighting the advantages of LARC over other methods.

“We do our best, we try to explain why we think we have the correct information, why this other information is not really correct, but the impact is there, you know? Not everybody makes decisions based on a cool dispassionate analysis of data.”

– Family medicine provider 1

Provider tenacity and enthusiasm for LARC were deemed important to sufficiently address patient concerns about LARC.

“I gave them a lot of reading on it, talked to them about it, tried to answer their questions and then had them come back and say, like, address it from there. Rather, and I think that's important, rather than just saying like, ‘Oh, okay, let's not do it. Let's move to something else.’ Like, to try and address it.”

– Pediatrician 3

Providers indicated that they would be interested in training on counseling, but also suggested that the biggest impediments to their counseling ability was that they felt their patients were disinterested in LARC. Some acknowledged their own tendency to address LARC last among all other methods and to not address it in great detail. Providers for whom the latter was true attributed this tendency to the fact that they did not provide LARC frequently or at all.

I'm just not as familiar with it. It doesn't, it just doesn't occur to me as quickly.

– Pediatrician 3

Effective counseling on LARC was judged a moot point for most providers who could not provide LARC themselves and perceived significant barriers to a patient procuring LARC through referrals. One exception to this trend stood out. An APN who was very enthusiastic about LARC for adolescents described lengthy, involved counseling sessions and had referred “10 or 12” adolescents to get LARC at another clinic. However, none of those patients had been able to successfully complete the referral process and ever actually obtained LARC. Providers who were able to provide LARC and had done so with adolescent patients in the past exhibited the most confidence in their counseling abilities while acknowledging that counseling on LARC is difficult but important.

Essential Component 3: Instrumental Supports for LARC Insertion

Training on LARC insertion, ability to provide LARC in-clinic, and access to LARC devices in clinic were all deemed instrumental supports to LARC provision for adolescents. Providers expressed desire for training on LARC insertion and wanted mentorship and oversight in practicing their skills.

“I personally always like to have somebody looking over my shoulder when I'm learning to do something, so if I had some sort of in-service and then knew that somebody was going to be there if I had some trouble, so that that patient didn't go away with the trauma of having----the potential trauma---of having an IUD put in and then no IUD. Like my patient, who, it took, like, four tries. Or four visits, rather.”

– APN 2

Many providers asserted that in addition to training, a “critical mass” of patients who want a LARC method is required for providers to become confident in placing these methods.

“I've been trained, but I haven't done it enough to actually do [an IUD insertion]. So I feel like I need to be trained again.”

- APN 1

Some providers who had been trained on LARC described difficulty securing devices. All providers were wary of scenarios in which an adolescent patient would have to be referred to a different clinic to get a LARC method. They expressed concern that despite their best efforts, patients would not follow up on the referral and would experience a disruption to contraceptive care.

All providers agreed that training on LARC insertion, sufficient opportunity to practice insertion and ability to provide LARC within their own clinic are supportive of LARC uptake among adolescent patients. Similarly, all providers agreed that the absence of these instrumental supports results in low uptake of LARC among adolescents.

Discussion

Essential Components for LARC Provision

Our results indicate that providers confront a variety of barriers to providing adolescents with LARC. Providers expressed varying degrees of confidence in negotiating individual barriers on their own, but these barriers do not exist independent of each other in practice. Each barrier is the consequence of and results in additional barriers. Providers' confidence in LARC as good methods for adolescents may increase if they perceive that adolescents are interested in learning about these methods. However, adolescents may not have an opportunity to demonstrate interest in these methods if, as our results suggest and contrary to guidelines for clinical practice, LARC methods are being offered by providers last, insufficiently, and sometimes not at all among all other methods. Similarly, providers indicated that they want support and training on counseling, but enhanced counseling may be of limited effect in actual uptake of LARC if adolescents are unable to obtain these methods at their regular clinic. Thus, provider confidence in LARC, patient-centered counseling, and instrumental supports for LARC provision influence each other and the eventual provision of LARC to adolescents such that when one component is undermined or absent, the others are impacted. In effect, the most salient threat to providing LARC to adolescents is not any particular barrier in and of itself, but in the interdependent nature of barriers to LARC provision, which sustains self-perpetuating cycles of low LARC uptake.

Where instrumental supports, provider confidence in LARC and patient-centered counseling on LARC are all present, we can assume that an adolescent who wants a LARC method should be able to procure one. Where all of the essential components are absent, LARC provision will likely be precluded. The key to increasing uptake of LARC among adolescents is to introduce support for LARC provision into one of the essential components where currently there is a lack of support for LARC, so that the self-perpetuating cycle of provider-based influences on adolescent uptake of LARC flows towards instead of away from LARC provision.

Instrumental Supports as Efficient Modes of Intervention

The results of this study suggest that the most efficient way to get all the essential components working together in support of adolescent LARC may be to increase instrumental supports for LARC, beginning with increased provider training on LARC insertion and expanded access to LARC devices for their clinics. Training on LARC should enhance providers' knowledge of eligibility criteria and side effect management strategies while emphasizing the importance of counseling on LARC as the most effective method of contraception first among all methods and in sufficient depth for patients to make an informed choice about LARC and their own contraception plans. Ensuring access to LARC devices in all clinical settings would allow providers who have been trained on LARC to provide LARC regularly, resulting in increased confidence with their LARC placement skills and the opportunity learn firsthand that LARC insertion is tolerable for adolescents. Increased access to LARC devices in a variety of clinic settings may also help normalize the concept of LARC methods among adolescents, so that patients are at least as familiar with LARC methods as they are with less effective methods.

Provision of instrumental supports for LARC will increase providers' LARC confidence and abilities such that adolescents who are open to learning about LARC will be more likely to obtain these methods. This recommendation is consistent with findings from previous research on LARC22-25. Future studies should assess the impact over time on providers' counseling skills and confidence in LARC methods with the introduction of provider training and increased access to LARC methods.

Primacy of IUD's Over Implants

It is worth noting that while our interview guide questions and prompts were all framed in terms of LARC, provider responses were often implicitly limited to IUD's. Discussions about LARC insertion as problematic for adolescents were common and lengthy, but typically centered on IUD insertion, exclusively. This disproportionate focus on IUD's was also observed in providers' discussions of LARC eligibility criteria and perceptions of patient disinterest in LARC. The meaning of this imbalance in terms of how LARC methods as a whole were discussed is unclear. Providers may perceive more barriers to IUD's than implants for adolescents and therefore discussed those barriers more often and in greater detail. Alternatively, providers may simply lack knowledge about implants as compared to IUD's. Future investigations should explore how providers conceptualize LARC, why IUD's may loom larger in that conceptualization than implants and what impact that potential imbalance has on counseling and provision of LARC to adolescents.

Limitations

The qualitative data gained from the convenience sample in this study allows for in-depth description of these providers' particular set of experiences and perspectives, but they cannot be generalized to a population outside of that which was involved in the study. Instead, these results should be interpreted in terms of evolving theory about providers' barriers and supports to adolescent LARC provision. The study design and findings may have been enhanced by use of an established theory of how innovations such as providing LARC to adolescents are adopted or rejected by potential users. Rogers' Diffusion of Innovations (1983) has been used to explain how family planning practices diffuse through healthcare systems and affect norms of care in developing countries26, and would have been a useful conceptual framework for this study, as well.

It is possible that participant responses were subject to social desirability bias, in that providers may have withheld information or viewpoints for which they felt they would be judged negatively. The study sample may over-represent providers who are particularly motivated to participate in a study about LARC because they are more interested in or enthusiastic about these methods, overall. Future studies should aim for larger samples of each provider type so that within-group similarities and differences can be explored.

Implications

A clinical culture supportive of LARC is critical to increased adolescent uptake of LARC. Such a culture is cultivated through expanded provider training and access to LARC devices. Interventions that increase these instrumental supports for LARC will enhance providers' abilities and confidence in providing LARC to adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant Number K12HD055892 from the NICHD and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH). The authors would like to thank the BIRCWH program and Dr. Connie Dallas at the College of Nursing, University of Illinois-Chicago. Results of this study were presented in a poster at the 29th meeting of the North American Society for Adolescent and Pediatric Gynecology.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities. Contraception. 2011;84:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.0113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trussel J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez G, Copen CE, Abma JC. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Health Stat. 2011;23(31):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Committee Opinion No. 539. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:983–988. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy Statement: Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):e1244–e1254. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research:ReportBrief. [Accessed June 15, 2015]; http://iom.nationalacademies.org/∼/media/Files/Report%20Files/2009/ComparativeEffectivenessResearchPriorities/CER%20report%20brief%2008-13-09.pdf. Published June 30, 2009.

- 7.Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007-2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming KL, Sokoloff A, Raine TR. Attitudes and beliefs about the intrauterine device among teenagers and young women. Contraception. 2010;82:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kavanaugh ML, Frohwirth L, Jerman J, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception for adolescents and young adults: Patient and provider perspectives. J Pediatr Adol Gynec. 2013;26:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohn JE, Hacker JG, Rousselle MA, Gold M. Knowledge and likelihood to recommend intrauterine devices for adolescents among school-based health center providers. J Adolesc Health. 2011;51:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potter J, Rubin SE, Sherman P. Fear of intrauterine contraception among adolescents in New York City. Contraception. 2014;89(5):446–50. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madden T, Allsworth JE, Hladky KJ, et al. Intrauterine contraception in Saint Louis: A survey of obstetrician and gynecologists' knowledge and attitudes. Contraception. 2010;81:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.002. doi:10.1016;j.contraception.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanwood NL, Garrett JM, Konrad TR. Obstetrician-gynecologists and the intrauterine device: A survey of attitudes and practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):275–280. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin SE, Fletcher J, Stein T, et al. Determinants of intrauterine contraception provision among US family physicians: A national survey of knowledge, attitudes and practice. Contraception. 2011;83:472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin SE, Campos G, Markens S. Primary care physicians' concerns may affect adolescents' access to intrauterine contraception. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(3):216–219. doi: 10.1177/2150131912465314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper CC, Blum M, de Bocanegra HK, et al. Challenges in translating evidence to practice: The provision of intrauterine contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1359–1369. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318173fd83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyler CP, Whiteman MK, Zapata LB, et al. Health care provider attitudes and practices related to intrauterine devices for nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:762–771. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824aca39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dehlendorf C, Tharayil M, Anderson N, et al. Counseling about IUDs: A mixed-methods analysis. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):133–40. doi: 10.1363/46e0814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haider S, Stoffel C, Cohen R. Long-acting Reversible Contraception for Adolescents: Addressing the Provider Barrier. J Womens Health. 2013;22(10):888. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landis JR, Koch GG. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg KB, Makino KK, Coles MS. Factors associated with provision of long-acting reversible contraception among adolescent health care providers. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:372–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricketts S, Klinger G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: Widespread use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(3):125–132. doi: 10.1363/46e1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin SE, Davis K, McKee MD. New York City physicians' views of providing long-acting reversible contraception to adolescents. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:130–136. doi: 10.1370/afm.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, et al. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1316–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy E. Diffusion of innovations: Family planning in developing countries. J Health Commun. 2004;9(1):123–129. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]