Abstract

Exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) not only can cause serious illness, but is also an economic and social burden. Contextual and individual factors of non-smoker exposure to SHS depend on location. However, studies focusing on this subject are lacking. In this study, we described and compared the factors related to SHS exposure according to location in Korea. Regarding individual factors related to SHS exposure, a common individual variable model and location-specific variable model was used to evaluate SHS exposure at home/work/public locations based on sex. In common individual variables, such as age, and smoking status showed different relationships with SHS exposure in different locations. Among home-related variables, housing type and family with a single father and unmarried children showed the strongest positive relationships with SHS exposure in both males and females. In the workplace, service and sales workers, blue-collar workers, and manual laborers showed the strongest positive association with SHS exposure in males and females. For multilevel analysis in public places, only SHS exposure in females was positively related with cancer screening rate. Exposure to SHS in public places showed a positive relationship with drinking rate and single-parent family in males and females. The problem of SHS embodies social policies and interactions between individuals and social contextual factors. Policy makers should consider the contextual factors of specific locations and regional and individual context, along with differences between males and females, to develop effective strategies for reducing SHS exposure.

Keywords: Environmental Tobacco Smoke, Contextual Effect, Exposure Location, Multilevel Analysis

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use is increasing in the world, and the health effects of secondhand smoke (SHS) are a public health issue. Exposure to SHS is associated with respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer (1,2). SHS caused 603,000 deaths and 10.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide, corresponding to 1.0% of all deaths and 0.7% of the worldwide burden of disease in DALYs (3).

Controlling tobacco and SHS prevalence is an important global public health challenge. In response to this issue, many countries are actively implementing a smoking ban policy in public and workplaces. However, exposure to SHS remains unacceptably high. In Korea, 36.1% of non-smokers are exposed to environmental tobacco smoke at work or at home (4).To address this problem, clarification of factors contributing to SHS exposure is important. While the socioeconomic and psychosocial determinants of smoking have been extensively researched, studies focusing on SHS determinants are lacking. Suggested factors related to SHS exposure include cultural and sex differences, socioeconomic factors, and health risk behaviors (5,6,7). Lower socioeconomic status (SES) increases the risk of SHS exposure (4,8,9,10).

However, factors contributing to SHS exposure in Korea are unclear. Active smoking is a voluntary behavior; however, exposure to SHS occurs passively and can affect nonsmokers. Therefore, specific contextual factors contributing to nonsmoker exposure to SHS depend on location and geographical region. To determine the factors affecting SHS, analyses conducted in different SHS exposure locations and at regional levels are needed. Understanding the contextual factors of SHS with respect to these parameters can help in the development of effective smoke-free policies in specific locations and areas. However, such studies are limited. Some studies have examined the home or workplace, with public spaces relatively neglected. Additionally, comparison of these three locations has not been widely performed. A study in Bangladesh indicated that the SHS exposure levels at home, in the workplace, and in public places vary markedly across socioeconomic and demographic subgroups (11). In the United States, a county-level study was conducted to account for individual and county-level differences of exposure to SHS in the workplace (12). However, to our knowledge, no studies have assessed the associations between these variables and SHS exposure based on different locations in Korea.

The present study was conducted to identify regional and individual factors contributing to SHS exposure according to location and gender and to identify variables most strongly associated with SHS exposure at each location.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and study population

Data in this study were obtained from the 2013 Korean Community Health Survey (KCHS) (13), the report of Development of Health Indicators for Community Health Ranking (DICR) (14), and the Korea No Smoking Guide website (15). This website introduces smoke-free policies and anti-smoking programs. It provides a wide variety of information on smoking in order to prevent and control smoking.

The KCHS was a nationwide survey that collected data from 253 local communities including 228,781 adults ≥ 19 years of age. The community health indicator study used a theoretically and empirically supported community health model. Health factors were measured in five domains of health behaviors including clinical care, social and economic factors, physical environment, and health policies. Both studies examined 253 communities, with Sejong city exempt from the community health indicator study and Yeongi county from the KCHS.

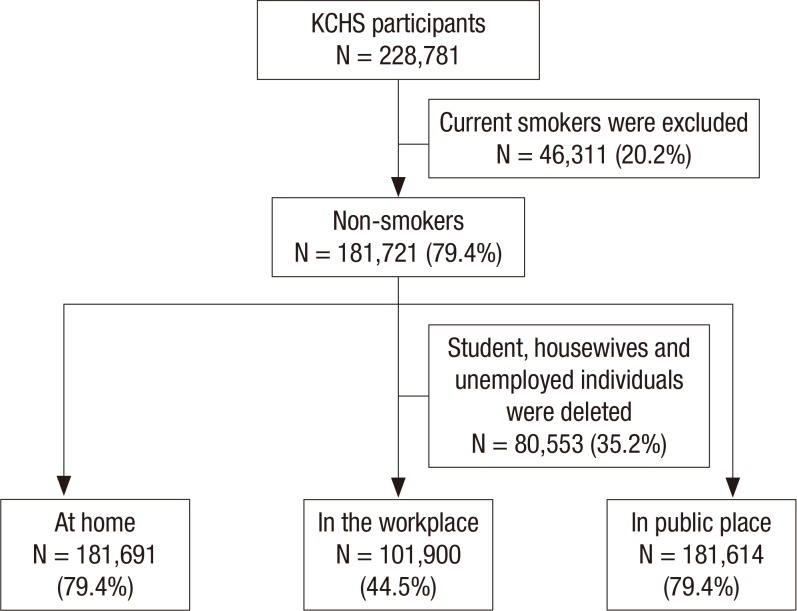

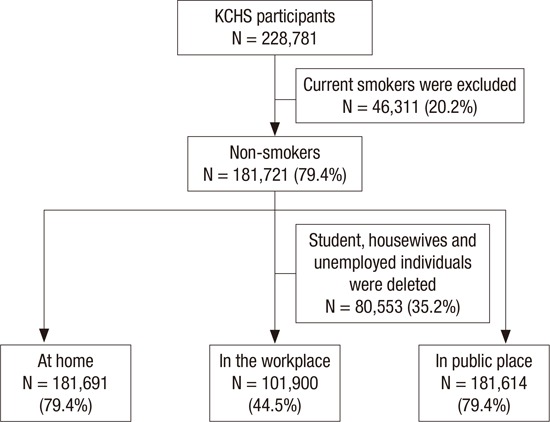

The 2013 KCHS included 228,781 adults ≥ 19 years of age who completed the interviews. Even though SHS is effective on both smokers and non-smokers, we assumed the effect on non-smoker is more harmful and important in public health, we only included non-smoker in our analysis. Among the participants, 46,311 (20.2%) active smokers were removed from the data in the present study. Finally, 181,721 (79.4%) non-smokers (including never smokers and ex-smokers) were used for analysis. Moreover, regarding SHS exposure in the workplaces, the data of students, housewives, and unemployed individuals (80,553, 35.2%) were excluded from the present study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Selection process of the study population sample.

Dependent variables

Dependent variables were SHS exposure at home, in the workplace, and in public places. Participants were asked questions regarding SHS exposure (hours per day) in these three locations. The questions were: “How many hours in a day exposure to SHS at home?”, “How many hours in a day exposure to SHS in work place?”, and “In recent 12 months, do you have exposure to SHS in public place?” The answers were recoded to yes (if participants were exposed) or no (if participants were not exposed, in other words, 0 hours exposure).

Independent variables

In previous studies, SHS exposure was analyzed in terms of socioeconomic factors including education, household income, employment, health-related factors, and place of exposure (5,6,7). In comparison to previous studies conducted in Korea (4,10), we selected home, workplace, and public place as SHS exposure locations and constructed a common individual variable model to evaluate SHS exposure in the three location types. The model assessed smoking status, individual socioeconomic differences (education, household income, location of residence), and health-related characteristics. In the location-specific model, housing and family type were used to estimate SHS exposure at home, and employment and occupation were used to estimate SHS exposure in the work place. Regional variables including health behavior and socioeconomic and health policy dimensions were evaluated for relationship with SHS exposure in public places.

A smoking status dummy was created with a score of 1 for never smoking and 2 for smoking. Average monthly household income variables were converted into a quartile index (scale 1–4, where 4 = above the third quartile). Locations of the residence dummy were scored as 1 for rural and 2 for urban. To assess the health status dimension, dummies of drinking and physical activity were used (1 for no and 2 for yes, respectively). Housing type dummies were constructed for detached house apartment, row house, multiplex house, commercial building house, and other dwelling types. Nineteen family type dummies were reconstructed into10 types (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants in 2013.

| Categorical variables | Male, No. | Proportion, % | Female, No. | Proportion, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and demographic factors | ||||

| Age | 60,051 | 100.00 | 121,670 | 100.00 |

| Younger (19-39 yr) | 13,862 | 23.08 | 30,672 | 25.21 |

| Middle-aged (40-59 yr) | 21,270 | 35.42 | 46,006 | 37.81 |

| Older (60 yr and older) | 24,919 | 41.50 | 44,992 | 36.98 |

| Education | 59,982 | 100.00 | 121,522 | 100.00 |

| ≤ Elementary school | 11,800 | 19.67 | 41,553 | 34.19 |

| Middle school | 7,746 | 12.91 | 13,231 | 10.89 |

| High school | 16,513 | 27.53 | 31,525 | 25.94 |

| College or higher | 23,923 | 39.88 | 35,213 | 28.98 |

| Household income yearly | 58,097 | 100.00 | 117,489 | 100.00 |

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 13,833 | 23.81 | 32,220 | 27.42 |

| 2nd quartile | 15,716 | 27.05 | 29,876 | 25.43 |

| 3rd quartile | 15,079 | 25.95 | 29,679 | 25.26 |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 13,469 | 23.18 | 25,714 | 21.89 |

| Location of residence | 60,051 | 100.00 | 121,670 | 100.00 |

| Rural area | 20,313 | 33.83 | 40,278 | 33.10 |

| Urban area | 39,738 | 66.17 | 81,392 | 66.90 |

| Health-related factors | ||||

| Smoking status | 60,040 | 100.00 | 121,664 | 100.00 |

| Never smoker | 25,044 | 41.71 | 118,647 | 97.52 |

| Ex-smoker | 34,996 | 58.29 | 3,017 | 2.48 |

| Drinking | 60,045 | 100.00 | 121,656 | 100.00 |

| No | 16,307 | 27.16 | 53,566 | 44.03 |

| Yes | 43,738 | 72.84 | 68,090 | 55.97 |

| Physical activity | 60,042 | 100.00 | 121,644 | 100.00 |

| No | 41,105 | 68.46 | 99,814 | 82.05 |

| Yes | 18,937 | 31.54 | 21,830 | 17.95 |

| Home-related factors | ||||

| Housing type | 60,051 | 100.00 | 121,670 | 100.00 |

| Detached house | 28,342 | 47.20 | 56,178 | 46.17 |

| Apartment house | 23,189 | 38.62 | 47,282 | 38.86 |

| Row house | 3,278 | 14.14 | 7,128 | 15.08 |

| Multiplex house | 3,837 | 16.55 | 8,401 | 17.77 |

| Commercial building house | 1,077 | 28.07 | 2,098 | 24.97 |

| Others | 328 | 8.55 | 583 | 6.94 |

| Family type | 60,051 | 100.00 | 121,668 | 100.00 |

| Single-person household | 3,915 | 6.52 | 16,355 | 13.44 |

| Couple | 20,935 | 34.86 | 29,920 | 24.59 |

| The first generation or other sibling or relatives | 750 | 1.25 | 1,663 | 1.37 |

| Couple with unmarried children | 23,863 | 39.74 | 45,642 | 37.51 |

| Single father with unmarried children | 916 | 1.53 | 554 | 0.46 |

| Single mother with unmarried children | 1,392 | 5.83 | 7,268 | 15.92 |

| Couple with their parent(s) | 1,482 | 2.47 | 3,483 | 2.86 |

| Grandparent(s) with unmarried grandchildren | 392 | 28.16 | 992 | 13.65 |

| Couple with children and couple's brothers or sisters or other type of second-generation family | 1,285 | 2.14 | 3,025 | 2.49 |

| Three-generation family | 5,121 | 8.53 | 12,766 | 10.49 |

| Work-related factors | ||||

| Employment | 43,153 | 100.00 | 62,483 | 100.00 |

| Employer and owner-operator | 19,044 | 44.13 | 14,577 | 23.33 |

| Paid worker | 23,216 | 53.80 | 37,624 | 60.21 |

| Unpaid family worker | 893 | 2.07 | 10,282 | 16.46 |

| Occupation | 43,242 | 100.00 | 62,578 | 100.00 |

| Officials or managers | 7,670 | 17.74 | 11,137 | 17.80 |

| Professionals | 5,670 | 13.11 | 8,599 | 13.74 |

| Service workers | 2,317 | 5.36 | 9,107 | 14.55 |

| Sale workers | 3,040 | 7.03 | 7,053 | 11.27 |

| Skilled agricultural or forestry or fishery | 10,744 | 24.85 | 13,618 | 21.76 |

| Craft and related trades workers, plant or machine operators assemblers | 8,971 | 20.75 | 2,777 | 4.44 |

| Manual laborer | 4,402 | 10.18 | 10,264 | 16.40 |

| Professional soldiers | 428 | 0.99 | 23 | 0.04 |

| SHS exposure | ||||

| At home | 60,049 | 100.00 | 121,659 | 100.00 |

| No | 57,685 | 96.06 | 107,318 | 88.21 |

| Yes | 2,364 | 3.94 | 14,341 | 11.79 |

| In the workplace | 42,170 | 100.00 | 59,739 | 100.00 |

| No | 31,992 | 75.86 | 49,995 | 83.69 |

| Yes | 10,178 | 24.14 | 9,744 | 16.31 |

| In a public place | 60,037 | 100.00 | 121,594 | 100.00 |

| No | 9,318 | 15.52 | 22,860 | 18.80 |

| Yes | 50,719 | 84.48 | 98,734 | 81.20 |

SHS, secondhand smoke.

* P value < 0.05 in all variables by χ 2 test.

Occupation dummies were constructed for officials or managers, professionals, service workers, sales people, skilled agricultural/forestry/fishery workers, craft and trade workers, plant or machine operators and assemblers, manual laborers, and professional soldiers. Employment dummies were constructed for employer or owner-operator, paid worker, and unpaid family worker.

Regional data collected in the DICR and included health behaviors (prevalence of active smoking, drinking rate, cancer screening rate) and socioeconomic characteristics such as high school graduation rate, unemployment rate, household income, and proportion of families with single parents or grandparents. Health policy data included health budget, financial autonomy, and smoke-free ordinance implementation. Smoke-free ordinance implementation in each region was obtained from Korea No Smoking Guide website. No ordinance implementing regions were categorized as 0, the regions with smoke-free ordinances implementation before December 31, 2011, between January 1 to December 31 in 2012, and between January 1 to December 31 in 2013, were categorized as 3, 2, 1, respectively. The definitions and units of regional variables are shown in Table 2. All regional variables were converted into a quartile index.

Table 2. The definitions and distribution of regional variables.

| Variables, Unit | No. of regions | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||

| 2013 prevalence of SHS, % | |||||

| At home | 252 | 8.9 | 1.76 | 20.6 | |

| In work place | 252 | 18.7 | 3.05 | 36.7 | |

| In public place | 252 | 86.2 | 21.64 | 96.8 | |

| Regional-level variables | |||||

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| Normalized household income (10,000 KRW/mon) | 252 | 166.6 | 81.5 | 335.7 | Total household income divided by the square root of the number of family members |

| High school graduation rates, % | 252 | 71 | 36.3 | 95.7 | Proportion of people older than 19 years who graduated from high school |

| Unemployment rate, % | 252 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 11.2 | Proportion of people older than 19 years who are unemployed |

| Proportion of family with single parents or grandparents only, % | 252 | 9 | 4.4 | 13.8 | Proportion of families who live with a single parent or grandparents only (with no parents) |

| Health behavior factors | |||||

| Prevalence of active smoking, % | 252 | 46.4 | 33.3 | 60.4 | Proportion of individuals who smoked more than five packs of cigarettes in their life time |

| Heavy drinking rate, % | 252 | 16 | 6 | 28.7 | Proportion of males who drank more than seven cups of alcohol or five cans of beer and females who drank more than five cups of alcohol or three cans of beer more than twice a week in the past12 months |

| Cancer screening rate, % | 252 | 49.4 | 20.4 | 66.4 | Proportion of people who received cancer screening within the past two years |

| Health policy | |||||

| Proportion of health budget, % | 252 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 8.7 | Proportion of total budget allocated to health |

| Financial autonomy, % | 252 | 65.4 | 32.8 | 90.1 | Percentage of financial independence assigned by the regional government |

| Year of smoke-free ordinances implementation | Regions were divided into the following four groups according to the years of smoke-free ordinance implementation; | ||||

| No implemented | 100 | — | — | — | 0. Not implemented; |

| In 2013 | 54 | — | — | — | 1. Implementation between January 1 to December 31, 2013; |

| In 2012 | 70 | — | — | — | 2. Implementation between January 1 to December 31, 2012; |

| Before and in 2011 | 28 | — | — | — | 3. Implementation before December 31, 2011 |

SHS, secondhand smoke.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses and multivariate regression analysis models were used. Logistic regression analysis was applied to estimate the relationships between common individual variables and SHS exposure in the three locations and to analyze the special variables of exposure to SHS at home and in the workplace. Multilevel analysis was used to detect factors affecting SHS exposure in public places because multilevel analysis is a suitable approach to take into account the social contexts as well as the individual factors in one model. Multilevel analysis allows several levels of analysis to be accounted for simultaneously and more effectively than in conventional multivariate analysis (16). The importance of a multilevel statistical approach for social epidemiology is discussed in other previous articles (17).

In multilevel analysis, individual characteristics, such as social and demographic factors (age, education, household income yearly, location of residence), Health-related factors (smoking status, drinking, physical activity) were set as the first level, and regional characteristics (Health behavior factors, Socioeconomic status, and Health policy dimensions) as the second level.

The associations between variables and SHS exposure were expressed in terms of odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical significance decisions were based on two-tailed p-values. All analyses excluded observations with missing information and were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To account for differential probabilities of selection, sampling weight was calculated for each respondent. These weights were used in the analysis to ensure regional representation. Cronbach's alpha was used to test the consistency in SHS exposure in the home/workplace/public locations.

Ethics statement

This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Sungkyunkwan University (IRB No: 2014-06-008). The board exempted submission of informed consent.

RESULTS

Variable characteristics

Characteristics of participants in 2013 are presented in Table 1, and χ 2 tests of all variables were statistically significant. Among the participants (non-smokers including never smokers and ex-smokers in 2013) 60,051 (26.2%) were male and 121,670 (53.2%) were female.

Cronbach's alpha coefficient for SHS exposure in the three different locations was 0.223, indicating inconsistency in SHS exposure in the three locations (data not shown). Prevalence of SHS ranged from 1.8% to 20.6% at home, 3.1% to 36.7% in the workplace, and 21.6% to 96.8% in public places.

Results of SHS exposure at home, in the workplace, and in public places based on sex

Multivariate analysis results were shown in Table 3, 4, and 5. Univariate analysis results showed no meaningful difference from multivariate analysis, only multivariate analysis results were shown in this article. In all three locals, younger age, drinking, and physical activity were positively associated with SHS exposure both in male and female non-smokers separately.

Table 3. OR and 95% CI of logistic regression analysis of SHS exposure at home.

| Categorical variables | At home | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Social and demographic factors | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Younger (19-39 yr) | Ref | |||

| Middle-aged (40-59 yr) | 0.384† | 0.341-0.432 | 1.022 | 0.971-1.076 |

| Older (60 yr and older) | 0.422† | 0.359-0.495 | 0.671† | 0.622-0.724 |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ Elementary school | Ref | |||

| Middle school | 0.891 | 0.742-1.069 | 0.928* | 0.867-0.994 |

| High school | 0.826† | 0.700-0.974 | 0.86† | 0.806-0.918 |

| College or higher | 0.695† | 0.581-0.832 | 0.593† | 0.550-0.640 |

| Household income yearly | ||||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | Ref | |||

| 2nd quartile | 0.972 | 0.842-1.121 | 0.999 | 0.942-1.061 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.935 | 0.803-1.090 | 0.955 | 0.895-1.020 |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 0.896 | 0.761-1.055 | 0.822† | 0.766-0.882 |

| Location of residence | ||||

| Rural area | Ref | |||

| Urban area | 0.995 | 0.896-1.106 | 1.058* | 1.012-1.106 |

| Health-related factors | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | Ref | |||

| Ex-smoker | 0.658† | 0.599-0.723 | 1.246† | 1.112-1.395 |

| Drinking | ||||

| No | Ref | |||

| Yes | 1.258† | 1.125-1.406 | 1.427† | 1.37-1.486 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| No | Ref | |||

| Yes | 1.33† | 1.217-1.454 | 1.297† | 1.241-1.355 |

| Home-related factors | ||||

| House form | ||||

| Detached house | Ref | |||

| Apartment house | 0.729† | 0.652-0.814 | 0.831† | 0.793-0.872 |

| Row house | 1.101 | 0.922-1.314 | 1.030 | 0.953-1.114 |

| Multiplex house | 0.903 | 0.758-1.075 | 1.031 | 0.957-1.111 |

| Commercial building house | 1.514† | 1.156-1.982 | 1.259† | 1.109-1.428 |

| Other | 1.029 | 0.601-1.759 | 1.044 | 0.799-1.363 |

| Family type | ||||

| Couple | Ref | |||

| Single-person household | 0.827 | 0.653-1.047 | 5.431† | 4.851-6.081 |

| The first generation or other sibling or relatives | 3.234† | 2.337-4.475 | 5.639† | 4.682-6.792 |

| Couple with unmarried children | 2.043† | 1.635-2.553 | 7.016† | 6.237-7.891 |

| Single father with unmarried children | 3.866† | 2.821-5.297 | 13.442† | 10.675-16.927 |

| Single mother with unmarried children | 1.485* | 1.082-2.039 | 3.743† | 3.262-4.296 |

| Couple with their parents or single-parent | 2.229† | 1.606-3.094 | 5.724† | 4.921-6.659 |

| Grandparents or single-grandfather or single-grandmother with unmarried grandchildren | 1.238 | 0.670-2.287 | 4.482† | 3.522-5.705 |

| Couple with children and couple's brothers or sisters or other type of second-generation family | 3.26† | 2.412-4.405 | 6.717† | 5.77-7.82 |

| Three-generation family | 2.456† | 1.920-3.141 | 6.951† | 6.144-7.865 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; SHS, secondhand smoke.

* P value less than 0.05; † P value less than 0.01.

Table 4. OR and 95% CI of logistic regression analysis of SHS exposure in the work place.

| Categorical variables | In the work place | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Social and demographic factors | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Younger (19-39 yr) | Ref | |||

| Middle-aged (40-59 yr) | 0.759† | 0.714-0.808 | 0.789† | 0.741-0.839 |

| Older (60 yr and older) | 0.492† | 0.449-0.539 | 0.478† | 0.431-0.531 |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ Elementary school | Ref | |||

| Middle school | 1.054 | 0.945-1.175 | 1.108* | 1.012-1.213 |

| High school | 1.024 | 0.926-1.132 | 0.855† | 0.784-0.933 |

| College or higher | 0.739† | 0.661-0.825 | 0.654† | 0.589-0.726 |

| Household income yearly | ||||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | Ref | |||

| 2nd quartile | 1.281† | 1.162-1.412 | 1.083 | 0.999-1.173 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.264† | 1.143-1.399 | 1.010 | 0.929-1.098 |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 1.15† | 1.035-1.277 | 0.863 | 0.790-1.042 |

| Location of residence | ||||

| Rural | Ref | |||

| Urban | 1.134† | 1.069-1.203 | 1.12† | 1.060-1.183 |

| Health-related factors | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | Ref | |||

| Ex-smoker | 1.037 | 0.987-1.091 | 1.262† | 1.086-1.468 |

| Drinking | ||||

| No | Ref | |||

| Yes | 1.334† | 1.250-1.425 | 1.295† | 1.228-1.367 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| No | Ref | |||

| Yes | 1.113† | 1.059-1.17 | 1.220† | 1.156-1.289 |

| Work-related factors | ||||

| Employment | ||||

| Employer and owner-operator | Ref | |||

| Paid worker | 1.151† | 1.081-1.225 | 0.641† | 0.602-0.683 |

| Unpaid family worker | 0.874 | 0.699-1.093 | 1.045 | 0.957-1.142 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Officials or managers | Ref | |||

| Professionals | 1.037 | 0.954-1.128 | 2.24† | 2.059-2.437 |

| Service workers | 1.511† | 1.353-1.687 | 2.621† | 2.395-2.868 |

| Sale workers | 1.449† | 1.309-1.605 | 1.715† | 1.556-1.89 |

| Skilled agricultural or forestry or fishery | 0.353† | 0.313-0.398 | 0.392† | 0.344-0.448 |

| Craft and related trades workers, Plant or machine operators and Assemblers | 1.82† | 1.683-1.967 | 1.886† | 1.668-2.133 |

| Manual laborer | 1.495† | 1.354-1.652 | 1.989† | 1.799-2.198 |

| Professional soldiers | 1.291* | 1.037-1.607 | 1.939 | 0.653-5.757 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; SHS, secondhand smoke.

* P value less than 0.05; † P value less than 0.01.

Table 5. OR and 95% CI of multilevel regression analysis of SHS exposure in a public place.

| Categorical variables | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Individual variables | ||||

| Social and demographic factors | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Younger (19-39 yr) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Middle-aged (40-59 yr) | 0.977† | 0.971-0.983 | 0.975† | 0.970-0.979 |

| Older (60 yr and older) | 0.955† | 0.948-0.963 | 0.934† | 0.927-0.941 |

| Education | ||||

| ≤ Elementary school | Ref | Ref | ||

| Middle school | 1.009 | 0.997-1.02 | 1.057† | 1.049-1.064 |

| High school | 1.011* | 1.001-1.022 | 1.068† | 1.061-1.075 |

| College or higher | 1.025† | 1.015-1.036 | 1.080† | 1.073-1.088 |

| Household income yearly | ||||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2nd quartile | 1.034† | 1.025-1.042 | 1.007† | 1.001-1.013 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.034† | 1.025-1.043 | 1.005 | 0.999-1.011 |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 1.031† | 1.022-1.041 | 0.998 | 0.992-1.004 |

| Location of residence | ||||

| Rural area | Ref | Ref | ||

| Urban area | 1.036* | 1.000-1.075 | 1.042* | 1.002-1.085 |

| Health-related factors | ||||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | Ref | Ref | ||

| Ex-smoker | 1.024† | 1.018-1.029 | 0.997 | 0.987-1.008 |

| Drinking | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.068† | 1.061-1.075 | 1.051† | 1.047-1.055 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.008† | 1.002-1.013 | 1.009† | 1.004-1.014 |

| Regional-level variables | ||||

| Health behavior factors | ||||

| Prevalence of active smoking | 1.012 | 0.992-1.012 | 1.002 | 0.991-1.013 |

| Heavy drinking rate | 1.024† | 1.003-1.023 | 1.014* | 1.003-1.025 |

| Cancer screening rate | 1.022 | 0.999-1.018 | 1.012* | 1.002-1.023 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Normalized household income | ||||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | Ref | |||

| 2nd quartile | 1.044 | 0.964-1.037 | 1.007 | 0.968-1.048 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.11 | 0.995-1.098 | 1.054 | 0.998-1.113 |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 1.129 | 0.980-1.100 | 1.059 | 0.993-1.129 |

| High school graduation rates | 1.028 | 0.983-1.024 | 1.007 | 0.985-1.031 |

| Unemployment rate | 1.007 | 0.991-1.01 | 0.996 | 0.985-1.007 |

| Proportion of family with single parents or grandparents only | 1.042 | 0.999-1.029 | 1.022† | 1.004-1.039 |

| Health policy | ||||

| Proportion of health budget | 1.004 | 0.994-1.015 | 1.006 | 0.994-1.018 |

| Financial autonomy | 0.999 | 0.988-1.010 | 0.997 | 0.984-1.009 |

| Year of smoke-free ordinance implementation | ||||

| No implementation | Ref | Ref | ||

| In 2013 | 1.006 | 0.977-1.036 | 0.999 | 0.967-1.032 |

| In 2012 | 1.015 | 0.984-1.047 | 1.018 | 0.984-1.054 |

| Before or in 2011 | 0.998 | 0.963-1.035 | 0.995 | 0.946-1.035 |

| Region variance (SE) | 0.302 (0.031) | 0.314 (0.030) | ||

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; SHS, secondhand smoke; SE: standard error.

* P value less than 0.05; † P value less than 0.01.

At home, male never-smokers were more likely to be exposed to SHS than ex-smokers while females showed opposite relation. High educational level in males and females was negatively associated with SHS exposure, and middle-level household income in females was positively related with SHS exposure. The results of home-related variables adjusted for common individual variables showed that single father and unmarried children family types were significantly associated with SHS exposure at home in males and females. Commercial building type of housing was positively associated with home SHS exposure, while apartment type was negatively associated.

In the workplace, living in an urban area, household income in males, and education in females were positively associated with SHS exposure, while only female ex-smokers had a positive relation with SHS exposure. In work-related factors, male paid workers demonstrated a positive association with SHS exposure, while female paid workers had a negative relation. Sales and service workers, blue-collar workers, and manual laborers were most significantly associated with SHS exposure in males and females.

In public places, living in an urban area, high educational level, and high income showed a positive relationship with SHS exposure in males and females. Male ex-smokers showed a positive relationship with SHS exposure. The model results indicated that drinking rate was positively associated with SHS exposure among male and female non-smokers, and cancer screening rate and single-parent family were positively associated with SHS exposure only in females. Year of smoke-free ordinance implementation did not show any significant relationship with SHS exposure.

DISCUSSION

SHS exposure has been linked to cultural and socioeconomic factors, as well as health risk behaviors (5,6,7). Our results regarding common individual variables indicate that exposure to SHS is associated also with socioeconomic status, with variations according to location. We observed substantial differences on SHS prevalence ranged from 1.8% to 20.6% at home, 3.1% to 36.7% in the workplace, and 21.6% to 96.8% in the public place. This means that the SHS effects on individuals are not homogeneous in each region. SHS is non-voluntary behavior and dependent on its contextual environments. Therefore, we included regional variables in this analysis and used more sophisticated analysis, multilevel analysis to consider regional effects at the same time.

In all three types of location, a trend of lower exposure with increasing age was observed in males and females. High SHS exposure among younger adults was previously reported in the United States, Canada, and some European countries (4,18,19). The smoking prevalence is reportedly higher in young Koreans than for the older population (20). Additionally, social environment has been linked to SHS behaviors in young Koreans. Young adults are likely to spend more time in smoky pubs and restaurants (21). Koreans are traditionally brought up to show respect for their parents, older persons, and persons of higher status (22); therefore, expressing a desire to avoid contact with a smoker is considered impolite or rude. As a result, young people are possibly more tolerant of smoking in all locations. This was also observed in a previous study in Korea (23).

Regarding drinking behavior, a positive association was found with SHS exposure in the three locations. In traditional Korean culture, smoking and drinking are considered normal means of facilitating social relationships (24). In addition, physical activity showed a positive association with SHS exposure in the three locations. People who participate in physical activity appear to have more opportunities to be exposed to SHS. Non-smokers might exercise or participate in a physical activity with their partners who are smokers, which could expose them to SHS.

At home, education was negatively associated with SHS exposure in males and females, indicating that people with a high educational level are less exposed to SHS. In general, highly educated males are rarely smokers. Additionally, it might be that females with a husband or boyfriend having a high educational level are rarely exposed to SHS at home.

We found that male ex-smokers were negatively associated with SHS exposure, but female ex-smokers showed a positive association. Exposure to SHS has been reported for ex-smokers in Korea and elsewhere (4,18,25,26). However, these previous studies did not estimate this variable based on exposure location. To the best of our knowledge, active smoking prevalence is higher among males than females, and most smokers are male. It is likely that, once the male in the household quits smoking, no smoker will remain in the family. For females, although they may quit smoking, their husband or boyfriend may be a smoker, creating a greater risk of exposure to SHS at home.

In home-related variables, our results showed that a single father with unmarried children had a strong positive association with SHS exposure at home in males and females. Usually, this type of family is most likely a broken family or has a low household income. Especially in a single-father family, the father’s smoking behavior is not regulated by a spouse, which may result in increased SHS exposure for the children. Paternal educational level was reportedly a decisive factor of SHS exposure. Fathers with a low educational level tend to smoke relatively more in the presence of their children (10), and children living with a father who smokes are more than three times likely to start smoking (27).

Additionally, people living in a commercial building type of housing had higher SHS exposure among both male and female non-smokers than those living in other housing types. Households with a higher SES can afford to buy or rent larger houses or flats and are more likely to be nonsmokers. Bad housing locations, crowded living conditions, low quality of housing, and aging public facilities have been associated with high SHS exposure at home (28,29), and our results are consistent with these findings. In addition, in Korea, the first and second floors in commercial building often house restaurants or bars, with people living above the businesses. People who live in this type of housing are more likely to be exposed to SHS.

In the workplace, our results showed a positive association between female ex-smokers and SHS exposure in the workplace, possibly because female ex-smokers work with other male or female colleagues who are current smokers, thus exposing them to SHS. In the work-related dimension, male paid workers demonstrated a positive relation with SHS in the workplace, while female paid workers showed a negative association. In Korea, male paid workers gather during breaks, and those who smoke may expose non-smokers to SHS. However, females might not smoke in the presence of their colleagues but smoke alone or only with other smokers.

Both male and female service workers, sale workers, blue-collar workers, and manual laborers showed a strong positive association with SHS exposure in the workplace. Service workers are mostly females and work in restaurants, coffee shops, and bistros, where nonsmokers experience the same level of exposure to SHS as do smokers (30). A previous article indicated that workers with lower social status are more likely to be exposed to SHS at work (31,32), which is consistent with our results. Individuals who are engaged in skilled manual work, sales, service, and simple labor jobs have much higher rates of SHS exposure at work than do other professions (4,31), and blue-collar and service workers are more likely to be employed at work sites that permit smoking (33). Previous studies have found that, compared with other workers, blue-collar workers smoke more heavily and are less successful at quitting smoking (34). Interestingly, in females, the ORs of professional and service workers were relatively higher than those of sale workers, blue-collar workers, and manual laborers. Professional females usually have high socioeconomic status and position. Similar to female employers, professional females may be at greater risk of exposure to SHS due to various reasons such as business meetings with others who are smokers.

When studied with regard to public places, living in an urban area, high individual education, and high income had a positive association with SHS exposure both in males and females. People with higher educational and income levels might be more aware of and sensitive to SHS exposure and perceive exposure to SHS as a health hazard. Furthermore, in high socioeconomic development regions where population density is increased, people are crowded into narrow places and are potentially more exposed to SHS.

Heavy drinking rate both in males and females is associated with a higher risk of exposure to SHS in public places. It means that not only individual drinking behavior but also regional contextual factor regarding drinking are associated with SHS exposure. Therefore, to reduce nonsmoker exposure to SHS, it is important to control the contextual and cultural factors regarding drinking also.

Moreover, we observed that the proportion of single-parent families both in males and females had a positive relationship with SHS exposure in public places, indicating again that single-parent families play an important role not only on the individual level, but also on the regional level.

Our study shows that smoke-free ordinance has no significant relation with SHS prevalence in public place. It might be indicated that impact of smoking and SHS control policy are limited. A previous study in Korea indicated that the effects of regional smoke-free ordinances revealed clear difference in rate of current smoking among males (35). The result is inconsistent with ours may be because that, this previous study focused on active smoking prevalence only among males, while our study focused on SHS prevalence and research objects were nonsmokers (most were female). In addition, as our study results shows, other contextual factors played more important roles in affecting SHS exposure among nonsmokers.

In summary, people with similar socioeconomic characteristics tend to be significantly exposed to SHS in different locations and regions. The affecting factors differ according to location and gender plays a different role regarding SHS exposure suggesting different gender culture regarding smoking behavior.

The present study had several limitations. First, as the survey was conducted annually, regional differences at the time of survey implementation could affect SHS prevalence calculations. Second, previous studies have shown that individual factors related to SHS exposure such as a family member smoking, friends or peer smoking, parental knowledge of anti-SHS, SHS attitude, and avoidance behavior were significantly associated with SHS exposure (36,37). Due to the limitation of this population-based survey, these factors could not be estimated; in addition, it is possible that some factors not be examined in the present study affect SHS exposure. We suggest that a qualitative study should be conducted with further exploration of factors affecting SHS exposure. Third, because each survey respondent had a different sensitivity to the SHS questionnaire, uneven recall bias might have occurred in the results.

Despite these limitations, our study is unique in several ways. Unlike previous studies, we focused on three exposure locations and indicated affecting factors in exposure to SHS based on location and gender. Furthermore, this study involved a substantial population sample and comprehensive data on several dimensions of socioeconomic position. Finally, this is the first study to assess contextual factors and SHS exposure in three types of location and on the regional level in Korea.

In conclusion, to implement effective policy strategies for reducing SHS exposure, the contextual factors of specific location and regional context should be considered. For example, not only should the ban on family smoking activities be actively advocated, but more SHS education and social support should be provided to single-father families. In dwellings with high SHS exposure, such as the densely populated commercial building type of housing, special supervision measures banning smoking should be implemented. In the workplace, a smoking ban could be linked to tax concessions, especially to small companies or family businesses. More social attention and enhanced anti-SHS education should be given to blue-collar and service workers. Social welfare and medical insurance treatment should also be improved. We recommend that special smoking regulations, surveillance, and legislation be established in public places, especially in places with high prevalence of smoking.

The SHS problem appears to be a social phenomenon. However, it embodies social policy and interactions between individuals and social contextual factors. Policy reforms and arduous and long-term efforts to improve contextual characteristics of SHS exposure in all locations are needed.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute, Ministry of Environment, Korea as "The Environmental Health Action program (2014001360001)".

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Study design: Sun LY, Park JH, Cheong HK, Kang KJ. Literature review: Sun LY. Data management and analyses: Sun LY, Lee EW. Interpretation of the findings and preparation of the manuscript: Sun LY, Park JH. Final approval: all authors.

References

- 1.Enstrom JE, Kabat GC. Environmental tobacco smoke and tobacco related mortality in a prospective study of Californians, 1960-98. BMJ. 2003;326:1057. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7398.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisner MD, Wang Y, Haight TJ, Balmes J, Hammond SK, Tager IB. Secondhand smoke exposure, pulmonary function, and cardiovascular mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Prüss-Ustün A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. 2011;377:139–146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee BE, Ha EH. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke among South Korean adults: a cross-sectional study of the 2005 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ Health. 2011;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin PL, Huang HL, Lu KY, Chen T, Lin WT, Lee CH, Hsu HM. Second-hand smoke exposure and the factors associated with avoidance behavior among the mothers of pre-school children: a school-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:606. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H, Hofstetter CR, Hughes S, Irvin VL, Kang S, Hovell MF. Changes in and factors affecting second-hand smoke exposure in nonsmoking Korean Americans in California: a panel study. Asian Nurs Res. 2014;8:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shwarz M, Collins BN, Nair US. Factors associated with maternal depressive symptoms among low-income, African American smokers enrolled in a secondhand smoke reduction programme. Ment Health Fam Med. 2012;9:275–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNabola A, Gill LW. The control of environmental tobacco smoke: a policy review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:741–758. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6020741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang DM, Hu Z, Orton S, Wang JJ, Zheng JZ, Qin X, Chen RL. Socio-economic and psychosocial determinants of smoking and passive smoking in older adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2013;26:453–467. doi: 10.3967/0895-3988.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi O, Kwon HJ, Kim D, Kim H, Ha M, Hong SJ, Hong YC, Leem JH, Sakong J, Lee CG, et al. Association between environmental tobacco smoke exposure of children and parental socioeconomic status: a cross-sectional study in Korea. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:607–615. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palipudi KM, Sinha DN, Choudhury S, Mustafa Z, Andes L, Asma S. Exposure to tobacco smoke among adults in Bangladesh. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:210–219. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris JK, Geremakis C, Moreland-Russell S, Carothers BJ, Kariuki B, Shelton SC, Kuhlenbeck M. Demographic and geographic differences in exposure to secondhand smoke in Missouri workplaces, 2007-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea community health survey [Internet] [accessed on 1 April 2016]. Available at https://chs.cdc.go.kr/chs/index.do.

- 14.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Development of health indicators for community health ranking [Internet] [accessed on 1 April 2016]. Available at http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/notice/CdcKrInfo0201.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU0004-MNU0007-MNU0025&fid=28&q_type=&q_value=&cid=20625&pageNum=1.

- 15.Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR) No smoke guide [Internet] [accessed on 1 April 2016]. Available at https://www.nosmokeguide.or.kr/mbs/nosmokeguide/

- 16.Pearce N. Traditional epidemiology, modern epidemiology, and public health. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:678–683. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honjo K. Social epidemiology: Definition, history, and research examples. Environ Health Prev Med. 2004;9:193–199. doi: 10.1007/BF02898100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skorge TD, Eagan TM, Eide GE, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in a general population. Respir Med. 2007;101:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu D, Wu X, Reynolds K, Duan X, Xin X, Reynolds RF, Whelton PK, He J; Cigarette smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in China: the international collaborative study of cardiovascular disease in Asia. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1972–1976. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S. Smoking prevalence and the association between smoking and sociodemographic factors using the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data, 2008 to 2010. Tob Use Insights. 2012;5:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarvis MJ, Feyerabend C, Bryant A, Hedges B, Primatesta P. Passive smoking in the home: plasma cotinine concentrations in non-smokers with smoking partners. Tob Control. 2001;10:368–374. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gannon MJ. Understanding Global Cultures: Metaphorical Journeys through 23 Nations. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes SC, Usita PM, Hovell MF, Richard Hofstetter C. Reactions to secondhand smoke by nonsmokers of Korean descent: clash of cultures. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:766–771. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SS, Son H, Nam KA. The sociocultural context of Korean American men\'s smoking behavior. West J Nurs Res. 2005;27:604–623. doi: 10.1177/0193945905276258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong BY, Lim MK, Yun EH, Oh JK, Park EY, Lee DH. Tolerance for and potential indicators of second-hand smoke exposure among nonsmokers: a comparison of self-reported and cotinine verified second-hand smoke exposure based on nationally representative data. Prev Med. 2014;67:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Twose J, Schiaffino A, García M, Borras JM, Fernández E. Correlates of exposure to second-hand smoke in an urban Mediterranean population. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, Abrams DB, Buka SL, Clark MA, Colby SM, Hitsman B, Kazura AN, Lipsitt LP, et al. Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: an intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e274–e281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim J. Neighborhood disadvantage and mental health: the role of neighborhood disorder and social relationships. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39:260–271. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles R. Neighborhood disorder and smoking: findings of a European urban survey. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2464–2475. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Global adult tobacco survey Poland 2009-2010 [Internet] [accessed on 1 April 2016]. Available at http://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/en_tfi_gats_poland_report_2010.pdf.

- 31.Moussa K, Lindström M, Ostergren PO. Socioeconomic and demographic differences in exposure to environmental tobacco smoke at work: the Scania Public Health Survey 2000. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32:194–202. doi: 10.1080/14034940310018183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regidor E, Gutierrez-Fisac JL, Calle ME, Navarro P, Domínguez V. Trends in cigarette smoking in Spain by social class. Prev Med. 2001;33:241–248. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerlach KK, Shopland DR, Hartman AM, Gibson JT, Pechacek TF. Workplace smoking policies in the United States: results from a national survey of more than 100,000 workers. Tob Control. 1997;6:199–206. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giovino GA, Pederson LL, Trosclair A. The prevalence of selected cigarette smoking behaviors by occupational class in the United States; Proceedings of Work, Smoking, and Health, a NIOSH Scientific Workshop; 2000 Jun 15-16; Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee HA, Park H, Kim H, Jung-Choi K. The effect of community-level smoke-free ordinances on smoking rates in men based on Community Health Surveys. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014037. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes SC, Corcos IA, Hofstetter CR, Hovell MF, Seo DC, Irvin VL, Park H, Paik HY. Secondhand smoke exposure among nonsmoking adults in Seoul, Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allem JP, Ayers JW, Unger JB, Vollinger RE, Jr, Latkin C, Juon HS, Park HR, Paik HY, Hofstetter CR, Hovell MF. The environment modifies the relationship between social networks and secondhand smoke exposure among Korean nonsmokers in Seoul and California. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27:NP437–NP447. doi: 10.1177/1010539512459750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]