Abstract

Pathogen components, such as lipopolysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria that activate Toll-like receptor 4, induce mitogen activated protein kinases and NFκB through different downstream pathways to stimulate pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression. Importantly, post-transcriptional control of the expression of Toll-like receptor 4 downstream signaling molecules contributes to the tight regulation of inflammatory cytokine synthesis in macrophages. Emerging evidence highlights the role of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) in the post-transcriptional control of the innate immune response. To systematically identify macrophage RBPs and their response to LPS stimulation, we employed RNA interactome capture in LPS-induced and untreated murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. This combines RBP-crosslinking to RNA, cell lysis, oligo(dT) capture of polyadenylated RNAs and mass spectrometry analysis of associated proteins. Our data revealed 402 proteins of the macrophage RNA interactome including 91 previously not annotated as RBPs. A comparison with published RNA interactomes classified 32 RBPs uniquely identified in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Of these, 19 proteins are linked to biochemical activities not directly related to RNA. From this group, we validated the HSP90 cochaperone P23 that was demonstrated to exhibit cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase 3 (PTGES3) activity, and the hematopoietic cell-specific LYN substrate 1 (HCLS1 or HS1), a hematopoietic cell-specific adapter molecule, as novel macrophage RBPs. Our study expands the mammalian RBP repertoire, and identifies macrophage RBPs that respond to LPS. These RBPs are prime candidates for the post-transcriptional regulation and execution of LPS-induced signaling pathways and the innate immune response. Macrophage RBP data have been deposited to ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD002890.

Activation of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)1 by bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), results in the induction of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and NFκB. The related specific signaling pathways stimulate pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression. Inflammatory mediators are essential to coordinate cellular responses to infection. Excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis disturbs the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately leading to systemic capillary leakage, tissue destruction, and lethal organ failure (1, 2). LPS induces genome-wide expression changes in alveolar macrophages and RAW 264.7 cells (3, 4). Following activation of inflammation-related genes (5, 6), post-transcriptional checkpoints are critical for the precise immune response modulation (7–9). Information about post-transcriptional mechanisms that regulate protein synthesis downstream of TLR4 to adjust the range and extent of the immune reaction is still fragmentary.

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that coordinate mRNA turnover and mRNA translation contribute to rapid and purposeful immune cell responses. Specific RBPs that interact with AU-rich elements (AREs) in mRNA 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTR) (ARE-BPs) have been shown to directly regulate cytokine mRNA translation and/or stability. AREs were first discovered in the short-lived human and mouse tumor necrosis factor (TNF) mRNAs (10). Besides TNF, ARE-BP-mediated regulation also controls the synthesis of other pro- and anti-inflammatory factors, such as interleukins and inducible nitric oxide synthase (7, 11, 12). Several ARE-BPs have been identified (7, 12): target mRNA translation is inhibited by T-cell-restricted intracellular antigen 1-related protein, CUG-repeat binding protein 2 and Fragile-X-related protein (13–15), whereas target mRNA decay is initiated by tristetraprolin (TTP), butyrate response factor 1 and 2 and KH-type splicing regulatory protein (16–18) through degradation factor recruitment. In contrast, Y-box binding protein 1 and Hu-antigen R (HUR) stabilize ARE-containing mRNAs (19–21), the latter has also been shown to regulate mRNA translation (22–24). Furthermore, AUF-1 (heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein D, HNRNP D) either inhibits or promotes target mRNA decay (25, 26). However, RBPs not only directly regulate stability and/or translation of cytokine mRNAs. Recently we could show that the synthesis of TLR4 downstream transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), an essential signaling molecule in accurate cytokine expression control, is controlled by HNRNP K in murine macrophages (27). In vitro RNA-binding assays revealed that the HNRNP K homology domain 3 of HNRNP K interacts specifically with a U/CCCC(n) motif in the TAK1 mRNA 3′UTR. HNRNP K depletion in macrophages did not affect TAK1 mRNA synthesis, but increased its translation. The resulting elevated TAK1 protein level changed the macrophage LPS response to an earlier and extended P38 phosphorylation, enhancing cytokine mRNA synthesis. This suggests that LPS-induced TLR4 activation abrogates TAK1 mRNA translational repression by HNRNP K and the newly synthesized kinase TAK1 boosts the macrophage inflammatory response (27).

To systematically identify regulatory RBPs that modulate the LPS-induced macrophage response, we employed RNA interactome capture (28) combining UV-induced protein-RNA crosslinking in LPS-activated and untreated RAW 264.7 macrophages with oligo(dT) capture of polyadenylated RNAs and bound RBPs after cell lysis, and subsequent identification of eluted proteins by mass spectrometry. Our analysis identified 402 RBPs in macrophages, referred to here as macrophage RNA interactome, including 91 proteins not previously annotated as RBPs. A comparison of the macrophage RNA interactome with the RNA interactomes of HeLa cells (29), HEK293 cells (30), and murine embryonic stems (ES) cells (31) identified 32 RAW 264.7 cell-specific RBPs. Of that group, 19 proteins that lacked RNA-related functional annotations were classified as novel macrophage RBPs. From these RAW 264.7 cell-specific RBPs we selected two candidates: P23, which acts as a heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) cochaperone (32) and was shown to possess cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase 3 (PTGES3) activity (33); and the hematopoietic cell-specific LYN substrate 1 (HCLS1, HS1), a hematopoietic cell-specific adapter molecule (34, 35). The poly(A)+ RNA binding activities of both proteins were validated by immunoprecipitation from cytoplasmic extracts; assaying recombinant proteins in vitro; and by immunofluorescence analysis combined with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in RAW 264.7 cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

pBSIIKS-firefly luciferase, pBSIIKS-firefly luciferase-pA (27), pBSIIKS-Renilla luciferase-pA (36), pGEM-CAT (37), and pET28b-PRMT1 (38) have been described. P23 (NM_019766.4) and HCLS1 (NM_008225.2) ORFs were PCR amplified from RAW 264.7 cDNA using the following primers: P23 fw: ttgtatctcgagatgcagcctgcttctg, P23 rv: gttagactcgagttactccagatctggc, HCLS1 fw: gcatgactcgagatgtggaagtctgtag, HCLS1 rv: gcatgactcgagttagaggagcttgaca and cloned into the XhoI site of pET16b. P23 fragments were cloned into the XhoI site of pET16b using the following primer pairs. P23 N (aa 1–130): P23 fw and P23 N rv: gttagactcgagttacatgtgatccatcatc; P23 C (aa 131–160): P23 C fw: ttgtatctcgagggtggtgatgaggatgt and P23 rv.

Cell Culture and LPS Treatment

RAW 264.7 cells (ATCC, Wesel, Germany, TIB-71) were grown in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), penicillin and streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For LPS treatment, 10 ng/ml E. coli LPS (serotype 0111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the medium for 2 h.

UV-crosslinking of RAW 264.7 Cells

Cells were kept on cell culture dishes and washed twice with ice-cold PBS. PBS was removed completely and culture dishes were placed on ice in a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), with 15 cm distance to UV bulbs. Cells were irradiated with UV light of 254 nm (0.15 J/cm2) and ice-cold PBS was added immediately after irradiation to harvest cells by scraping.

RBP Capture

In two independent biological replicate experiments the following conditions were compared: 1] LPS treatment (+LPS), UV-crosslinking (+CL), 2] no LPS (-LPS) (+CL), 3] control (ctrl.) (+LPS) noncrosslinked (no CL), 4] ctrl. (-LPS) no CL (Fig. 1A). Enrichment and isolation of RBPs bound to polyadenylated RNA was performed as described (28, 29). For each sample 40 million cells were used. Crosslinked cells were collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 500 × g and 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 35 ml ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 500 mm LiCl, 0.5% LiDS, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm DTT) and incubated on ice for 10 min. For homogenization the lysate was passed three times through a 26G needle. Polyadenylated Renilla luciferase RNA (Renilla poly(A)+) and nonpolyadenylated firefly luciferase RNA (Firefly poly(A)−) were added as spike in-controls. Three milliliters magnetic oligo(dT)25-beads or magnetic nonmodified beads (NEB, Ipswich, MA) were activated by washing three times with 9 ml lysis buffer. Beads were incubated with the lysate for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation. All following washing steps were performed at 4 °C. Separation of beads and supernatant was performed in a magnetic separation rack (NEB). The supernatant was used for a second round of isolation. Beads were sequentially washed 5 min with rotation in 35 ml of the following buffers: lysis buffer, buffer I (twice) (20 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 500 mm LiCl, 0.1% LiDS, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm DTT), buffer II (twice) (20 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 500 mm LiCl, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm DTT) and buffer III (twice) (20 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 200 mm LiCl, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm DTT). RNA-protein complexes were eluted by addition of 0.5 ml elution buffer (20 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 1 mm EDTA) and incubation for 3 min at 50 °C with shaking at 750 rpm. Empty beads were regenerated by washing three times with 9 ml lysis buffer and then reincubated with the supernatant. A second isolation was performed as described above and both eluates were combined afterward.

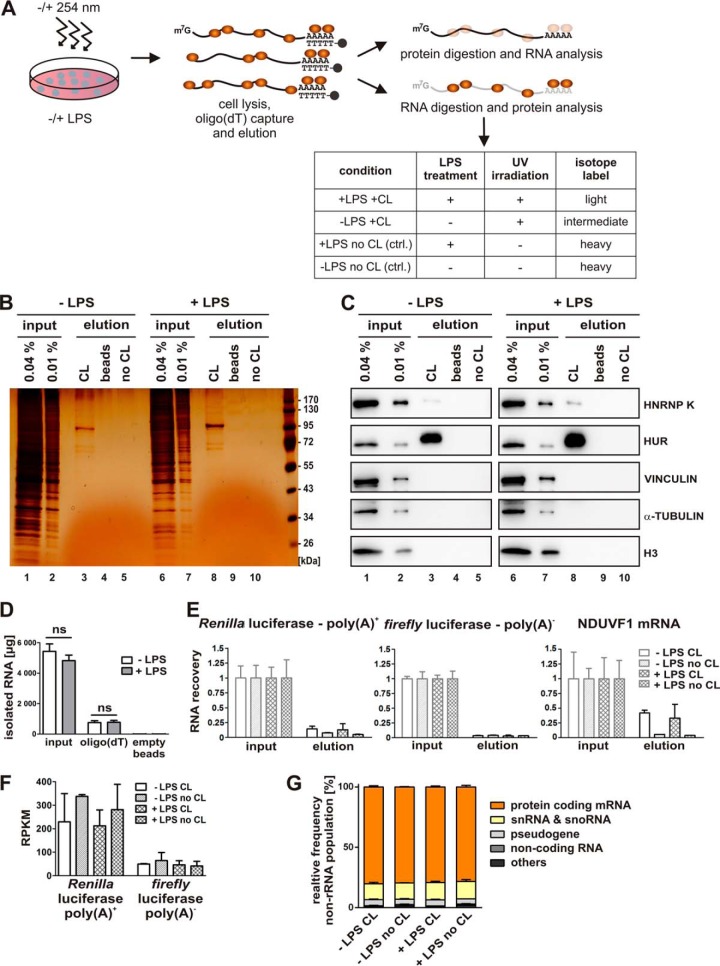

Fig. 1.

RBP enrichment by in vivo UV-crosslinking and oligo(dT) capture. A, Experimental design. RAW 264.7 cells were either left untreated or induced with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h and subsequently UV-irradiated (λ = 254 nm) (crosslinked, CL) to stabilize RNA-protein interactions. To enrich poly(A)+ RNA, RNA-protein complexes were subjected to oligo(dT) capture after cell lysis and eluted, treated either with proteinase K to purify the RNA or with RNase A/T1 for Western blot analysis and mass spectrometry. B and C, Following RNase A/T1 digestion, released proteins were analyzed by silver staining (B, lanes 1–10) or with antibodies specific for known RBPs (HNRNP K and HUR) or control proteins (VINCULIN, α-TUBULIN and histone H3) (C, lanes 1–10). Beads lacking oligo(dT) (beads) or preparations from non-UV-irradiated cells (no CL) served as controls. D, Total amounts of isolated RNA from input and elution from oligo(dT)- and empty magnetic beads. E, QPCR analysis of RNA isolated from the input and the oligo(dT)-bound fraction following proteinase K treatment of the beads, performed in triplicates. Equal proportions of the input and eluate samples were used for qPCR analysis. Primers against spike-in controls, which were added prior to oligo(dT) capture, polyadenylated Renilla luciferase mRNA (Renilla poly(A)+), nonadenylated firefly luciferase mRNA (firefly poly(A)−) or endogenous NDUFV1 mRNA were used. F, Quantification of Renilla luciferase-poly(A)+ and firefly luciferase-poly(A)− from high throughput sequencing of eluted RNAs. Raw read counts were normalized for total read length and the number of sequencing reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM). G, High throughput sequencing of eluted RNAs. The percentage of non-rRNA reads mapped to the mouse transcriptome is displayed. Noncoding RNAs comprise miRNAs, lncRNAs and asRNAs.

Isolation of Proteins

For analysis of coprecipitated proteins covalently bound RNAs were digested by RNase treatment. Samples from input and eluate were incubated with 5×RNase buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 750 mm NaCl, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, 2.5 mm DTT), 280 U RNase T1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 4 μg RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at 37 °C. Reaction mixtures were concentrated with an Amicon Ultra 10000 MWCO (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA) by centrifugation (3.220 × g, 4 °C, 45 min), and the upper reservoir was refilled twice with buffer IV (10 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl).

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

In each of two replicate experiments, three samples were compared: (1) LPS treatment (+LPS), UV-crosslinking (+CL), (2) no LPS (-LPS) (+CL) and (3) controls (ctrl.) (+LPS, -LPS), both noncrosslinked (no CL). Controls were combined because they contain only few proteins and the background was usually fairly constant. Protein samples were processed as described before (28, 29). Briefly, proteins were digested, followed by a stable-isotope labeling step via reductive methylation (using differential labels producing “light,” “intermediate,” and “heavy” peptides in the respective samples) (Fig. 1A). Samples were combined, and peptides were fractionated by isoelectric focusing. The twelve fractions generated were analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC) coupled to an OrbitrapVelosPro mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a Proxeon nanospray source. Reverse phase chromatography was performed with a nanoAcquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA) fitted with a trapping column (nanoAcquity Symmetry C18, 5 μm, 180 μm×20 mm) and an analytical column (nanoAcquity BEH C18, 1.7 μm, 75 μm × 200 mm) directly coupled to the ion source. The mobile phases for LC separation were 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in LC-MS grade water (solvent A) and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in can (solvent B). Peptides were separated at a constant flow rate of 300 nl/min with a linear gradient of solvent B from 3 to 40% for 145 min. The MS1 scan was acquired in the Orbitrap from m/z 300 to 1700 at a maximum filling time of 500 ms and 106 ions. The resolution was set to 30,000. Fragmentation was performed in the LTQ by collision induced dissociation, selecting up to 15 most intense ions (top15) at an isolation window of 2 Da. Target ions previously selected for fragmentation were dynamically excluded for 30 s with relative mass window of 10 ppm. MS/MS selection threshold was set to 2000 ion counts. A lock mass correction was applied using a background ion (m/z 445.12003).

MS Data Processing

Raw files were processed with MaxQuant version 1.3.0.5 (39) and the Andromeda search engine (40). The MS/MS spectra were searched against the Mouse SwissProt database (downloaded on June 21, 2011) containing 53,623 forward sequences that was appended to the same number of reverse sequences and 265 common contaminants. The precursor mass tolerance was set to 20 ppm for the first pass and 6 ppm for the second pass. The fragment mass tolerance was 0.5 Da. Razor peptides, which represent nonunique peptides assigned to the protein group with the most other peptides, following Occam's razor principle (39) and unique peptides were quantified only as unmodified peptides. Cysteine carbamidomethylation and methionine oxidation were set as fixed and variable modification, respectively. The minimum peptide length was set to six amino acids, the enzyme specificity was set to trypsin/P, the maximum allowed miss-cleavage was set to 2, and the false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 0.01 for both peptide and protein identifications. Requantification and match between runs were also performed unless stated otherwise. The protein identification was reported as a “protein group” if no unique peptide sequence to a single database entry was identified. Statistical analysis was performed using the Limma package in R/Bioconductor (41, 42) calculating FDRs from p values using Benjamini and Hochberg's method. When comparing crosslinked cells (either untreated or after LPS-stimulation) to noncrosslinked controls, a protein was regarded as an RNA interactor, if the adjusted p value was <0.1 and when ratios in both replicates changed in the same direction. When comparing untreated and LPS-stimulated cells to each other, a protein was considered to differentially bind to mRNA between these conditions if the adjusted p value was <0.1 and when ratios in both replicates changed in the same direction. For RBP classification, data were collapsed to unique gene names (supplemental Table S2). The MaxQuant output text files with the raw mass spectrometry data have been deposited via the PRIDE partner repository in ProteomeXchange (43) and individual peptides can be viewed in the MaxQuant viewer. The ProteomeXchange accession number is PXD002890.

Statistical Analyses

Enrichment analyses were performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (44, 45). A p value was calculated, applying a modified Fisher's exact test (EASE score) for each term and corrected for multiple testing with Benjamini and Hochberg's method. The following criteria were applied: EASE score ≤0.1, at least three proteins could be assigned to one term and corrected p value ≤0.05.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

In each of the two replicate experiments, three samples were compared: 1] LPS treatment (+LPS), UV-crosslinking (+CL), 2] no LPS treatment (-LPS), UV-crosslinking (+CL), and 3] controls (+LPS, -LPS), both noncrosslinked (no CL). The controls (ctrl.) of the two experiments were combined because they contain only few proteins, and the background was usually fairly constant. We have digested each of these three protein samples, followed by a stable-isotope labeling step producing light, intermediate, and heavy peptides in the respective samples (Fig. 1A). Statistical analysis was performed with the Limma package in R/Bioconductor (41, 42) applying adjustment of p values for multiple testing with Benjamini and Hochberg's method.

RNA Preparation and Quantitative Real-time PCR

For analysis of precipitated RNA covalently bound proteins were removed by proteinase K. Samples from input and eluate were preincubated with 5× proteinase K buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 750 mm NaCl, 1% SDS, 50 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm DTT, 25 mm CaCl2), and 40 U RiboLock (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at 65 °C. After addition of 20 μg proteinase K, samples were incubated for 1 h at 50 °C. 250 pg CAT RNA (RBP capture) or firefly luciferase RNA (immunoprecipitation and poly(A)+ capture) were added prior to total RNA extraction using Trizol. For reverse transcription random primers and M-MLV RT (Promega, Madison, WI) or Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used (46). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix on a StepOnePlus (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primers are summarized below. For analysis of spike in-control RNAs equal volumes were analyzed by qPCR. RNA levels were determined by the ΔΔCt method (47), normalized for CAT RNA. RT-PCR with primers for firefly luciferase as extraction control was performed as described (48).

Nano Chip Analysis

RNA samples from input and elute fractions were analyzed with an RNA 6000 Nano Kit on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The 28S/18S ratio and the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) (49) were indicated as a measure for RNA quality.

High-throughput Sequencing

RNA samples from the eluate fractions were analyzed by high-throughput sequencing. RNA was chemically fragmented (NEBNext Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module) for 4 min at 94 °C to an average length of ∼140 nt, and converted into an Illumina-compatible library using the Split Adapter method as described (50), omitting the hot SPRI bead cDNA purification step and the DSN depletion step. Amplified libraries were size-selected by polyacrylamide electrophoresis. Yield and quality were checked by running libraries on a Bioanalyzer chip. Library sequencing was performed on an Illumina miSeq sequencer (Biomolecular Resource Facility, Australian National University). Reads were mapped to the mouse transcriptome and all non-rRNA reads were assigned to categories.

In Vitro Transcription

RNA for spike in controls and for extraction control was transcribed with T7 MEGAscript® Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Antibodies

Antibodies were purchased from Abcam, Cambridge, UK (HISTONE H3, P23), Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX (HNRNP K, HUR), Sigma-Aldrich (α-TUBULIN, VINCULIN), Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA (HCLS1) and GE Healthcare Life Sciences (HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies).

Immunoblot Analysis

Western blot assays were performed as described previously (51) and analyzed on a LAS-4000 system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Freburg, Germany).

Immunofluorescence and Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH)

Immunofluorescence staining was essentially performed as described in (48) with specific antibodies against HCLS1 and P23 and FISH with an oligo(dT) probe as in (52).

Immunoprecipitation

Crosslinked RAW 264.7 cells were collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 500 × g and 4 °C and lysed in 1 volume IP buffer (46) by passing ten times each through a 20G and subsequently a 26G needle. Supernatant representing cytoplasmic extract was stored at −80 °C. Anti-P23 or anti-HCLS1 antibodies were incubated with 40 μl Protein G Sepharose overnight at 4 °C. Antibody coupled beads were incubated 2 h with 1 mg cytoplasmic extract derived from RAW 264.7 cells (untreated or 2 h LPS-induction) in IP buffer. Luciferase control IP was performed as described (27). Beads were washed twice in IP buffer and either boiled in 2× SDS sample buffer for Western blot analysis or resuspended in Trizol for RNA isolation.

Expression of Recombinant Proteins

His-tagged protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (His-PRMT1) was expressed as described (53). His-P23 and peptide variants as well as His-HCLS1 were expressed as described for His-HNRNP K (54).

Pulldown of His-tagged Proteins

Forty pmol His-P23 and peptide variants, His-HCLS1 or His-PRMT1 were immobilized on 30 μl Ni-NTA agarose in IP buffer and subsequently incubated with 50 μg of total RNA isolated from untreated or LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Coprecipitated RNA was isolated using Trizol with firefly luciferase RNA as extraction control.

Poly(A)+ RNA Detection Assay

RNA isolated from immunoprecipitation or pull down assays was dot blotted on a nylon membrane, crosslinked twice (XLE-1000, Spectroline, Westbury, NY setting Optimal Crosslink) and hybridized with Biotin-(dT)30 in 4×SSC, 1% bovine serum albumin, 2.5% dextran sulfate overnight at 4 °C. Bound Biotin-(dT)30 was detected by Streptavidin-HRP. Data from three independent experiments were evaluated using Student's t test (* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001).

RESULTS

Comprehensive analysis of RNA-bound RBPs in Differentially Treated Macrophages

Stability and translation of several cytokine mRNAs is controlled by ARE-BPs (7, 10–12). In addition, HNRNP K was identified as a specific regulator of TAK1 mRNA translation in LPS-induced macrophages (27). We aimed to systematically analyze RBPs that modulate the macrophage LPS response. To characterize the differential RNA-binding properties of RBPs in untreated and LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages we applied RNA interactome capture, which had already successfully been employed to determine the RBP repertoire in other contexts (28–31, 55).

To capture early regulatory interactions, we used a 2 h LPS-treatment, based on LPS time-course experiments (27). Native RNA-protein complexes were crosslinked (CL) by UV light (λ = 254 nm) in vivo, cells were lysed, polyadenylated RNAs bearing the crosslinked RBPs purified on oligo(dT) beads, and treated with RNases A/T1 or proteinase K to purify the RBPs or RNAs, respectively, for further analysis (Fig. 1A). Protein capture with poly(A)+ RNA was strongly enhanced by UV irradiation as confirmed by silver staining (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 3 and 8 with 5 and 10). The protein elution pattern differs profoundly from the input (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–3 and 6–8), indicating selectivity against protein abundance and specificity of RNA binding.

HNRNP K (27) and HUR (20–24), which are RBPs known to mediate post-transcriptional control of protein synthesis, were specifically enriched in oligo(dT) eluates of UV-irradiated samples from untreated and LPS-induced cells, as validated by Western blotting (Fig. 1C, lanes 3–5 and 8–10). In contrast, the abundant cellular proteins VINCULIN, α-TUBULIN and HISTONE H3 were not detected in the eluates (Fig. 1C, lanes 3–5 and 8–10). RNA isolation from the input and elution from the oligo(dT)-beads yielded comparable total RNA amounts for the samples from untreated and LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells, indicating no major changes in the overall mRNA pool, bound to oligo(dT) (Fig. 1D). QPCR analysis further demonstrated that specific RNA amounts eluted from oligo(dT) were comparable independent of macrophage LPS treatment (Fig. 1E). The yield of exogenously added polyadenylated Renilla luciferase mRNA (Renilla poly(A)+) was higher than that of nonadenylated firefly luciferase mRNA (firefly poly(A)−) (Fig. 1E, left and middle panel). This was supported by the relative abundance of the two spike-in controls in the elution fractions as quantified by RNA-Seq (Fig. 1F). In addition to the exogenously added mRNAs we investigated binding of an endogenous mRNA encoding NDUFV1 that is expressed constitutively in untreated and LPS-induced macrophages (27). Forty percent of NDUFV1 mRNA was recovered in the elution of the crosslinked samples compared with input (Fig. 1E, right panel). The analysis of the eluted nonribosomal RNA population by limited high-throughput sequencing revealed that mRNAs represent the major fraction of nonribosomal RNA, independent of macrophage LPS-induction or UV-crosslinking prior to oligo(dT) capture (Fig. 1G).

These data indicate that the UV-induced crosslinking between RNAs and RBPs was effectively established, whereas abundant proteins that lack RNA-binding activity could not be detected.

Classification of RBPs in RAW 264.7 Cells

To characterize the protein pool that is bound to polyadenylated RNA, RBPs from untreated and LPS-induced macrophages were analyzed by mass spectrometry in two independent biological replicate experiments (for details see Experimental Procedures, LC-MS/MS). In total 945 proteins were identified (supplemental Table S1), 762 of them were identified in both replicates (supplemental Table S2). Of these, 374 and 396 unique proteins were enriched compared with the noncrosslinked control in the samples of untreated and LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells, respectively (Fig. 2A, supplemental Table S2). There was a very high overlap of 368 proteins between the -LPS and +LPS samples (Fig. 2B), leaving 402 proteins that we define here as the collective set of RBPs in mouse macrophages. Among them, six proteins were identified as RNA-interactors in untreated macrophages and 28 in LPS-induced macrophages, but did not pass the criteria to be considered as RNA-interactors in the other condition (Fig. 2B) (for details see Experimental Procedures, MS Data Processing).

Fig. 2.

RAW 264.7 macrophage RNA interactome. A, Log2 ratios of proteins identified in two biological replicates from untreated RAW 264.7 cells (-LPS CL) normalized to non-UV-irradiated cells (no CL) (left) and 2 h LPS-induced cells (+LPS CL) normalized to UV-irradiated cells (no CL) (right). Proteins represented in the RNA interactome are indicated in orange. B, Overlap of RBPs enriched from untreated and LPS-induced cells. C, GO domain analysis of Molecular Function (top) and Biological Process (middle), and top ten protein classification based on Pfam (bottom). Terms with lowest adjusted p values corrected for multiple testing by Benjamini and Hochberg's method are displayed. Numbers in brackets indicate proteins identified versus the total number of mouse genome encoded proteins according to DAVID (44, 45). D, Classification of the identified RNA interactome as proteins implicated in RNA binding, RNA related, nucleic acid binding or related and as proteins not related to nucleic acid binding.

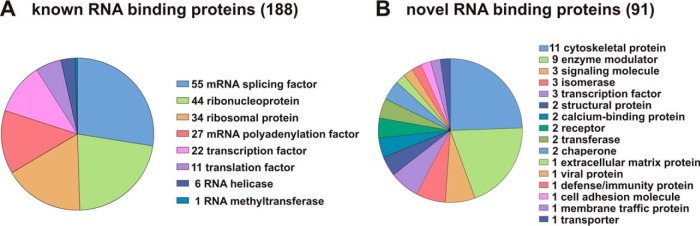

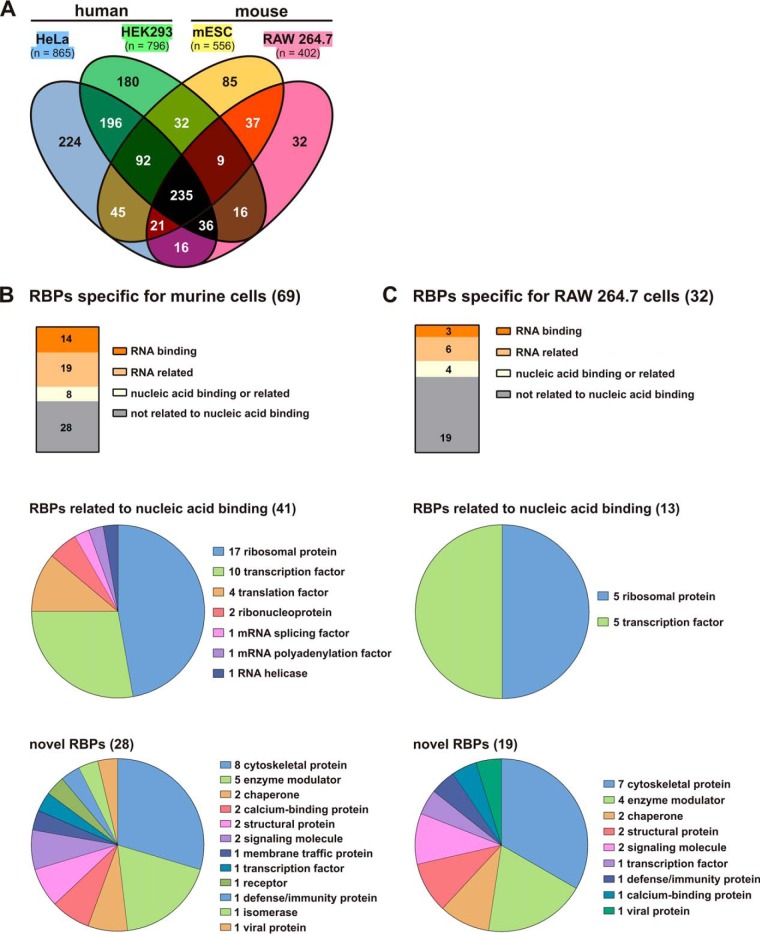

Within this macrophage RNA interactome we applied mouse genome-based gene set enrichment analysis to search for representative features (44, 45) (Fig. 2C). As predicted, in the gene ontology (GO) domain Molecular Function “RNA binding” is the most significantly over-represented category of the 402 proteins with 12.5-fold enrichment compared with the mouse genome (Fig. 2C, top panel). Consistently, in the GO domain Biological Process, RNA biology-related functions and processes are highly over-represented (Fig. 2C, middle panel) and protein domain analysis (Pfam) finds RNA recognition motifs (RRM) as predominant (Fig. 2C, bottom panel). Interestingly, only 188 of the 402 candidate proteins represent annotated RBPs. Examination of the remaining 214 proteins identified 80 as RNA related and 43 as nucleic acid binding or related. Notably, 91 proteins were not related to nucleic acid binding (Fig. 2D). To further investigate protein functions we extended our GO and Pfam analysis by using Panther Protein class annotation (56, 57). This revealed that the 188 proteins categorized as RBPs bear functions from RNA synthesis to RNA processing, RNA modification and mRNA translation some of them have multiple functions (Fig. 3A). For several of the 91 proteins, so far not classified as related to nucleic acid binding, cellular functions linked to a broad range of processes are reported (56) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Known and novel RBPs. A, Classification of 188 known RBPs according to functions in RNA metabolism based on Panther (http://www.pantherdb.org/) (56, 57). To some proteins several functions are allocated. B, 91 novel RBPs categorized based on Panther, several proteins were not classified.

RBPs Specifically Identified in Murine Macrophages

To identify cell-specific RBPs we compared the murine macrophage RNA interactome with previously published RNA interactomes of murine ES cells (31) and two human cell lines, HeLa (29) and HEK 293 (30) (Fig. 4A). This analysis classified 69 proteins only identified in murine cells (Fig. 4A and 4B), of which 32 were exclusively detected in macrophages (Fig. 4A and 4C). This group of 32 RBPs only identified in macrophages includes 19 proteins (Fig. 4C) with activities so far not directly related to RNA (Table I).

Fig. 4.

Identification of RAW 264.7 macrophage-specific RBPs. A, Comparison of the RAW 264.7 RNA-interactome with that of HeLa cells (29), HEK293 cells (30) and murine ES cells (31). B, Classification of 69 murine-specific RBPs in RNA- or nucleic acid binding and nonrelated proteins (top), assignment of 41 nucleic acid binding related RBPs to RNA metabolism (middle) and mapping of 28 novel proteins to cellular functions (Panther protein class annotation) (bottom). C, Assignment of 32 RAW 264.7 cell-specific RBPs to RNA- or nucleic acid binding and nonrelated proteins (top), 13 nucleic acid binding related RBPs to RNA metabolism (middle) and mapping of 19 novel proteins to cellular functions (Panther protein class annotation) (bottom).

Table I. 32 macrophage-specific RBP candidates in the RAW 264.7 cell interactome.

| Gene symbol | ENSEMBL ID | Gene name | Panther (protein class) | Protein domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA binding | ||||

| Phax | ENSMUSG00000008301 | Phosphorylated adapter RNA export protein | nucleic acid binding | Phosphorylated adapter RNA export protein, RNA-binding domain |

| Prkrip1/C114 | ENSMUSG00000039737 | PRKR-interacting protein 1 | ||

| Rpl12 | ENSMUSG00000038900 | 60S ribosomal protein L12 | nucleic acid binding | |

| RNA related | ||||

| Gm10119 | ENSMUSG00000062611 | 40S ribosomal protein S3a | nucleic acid binding | |

| Gm10154 | ENSMUSG00000066116 | 60S ribosomal protein L34 | nucleic acid binding | |

| Hic2 | ENSMUSG00000050240 | Hypermethylated in cancer 2 protein | nucleic acid binding, transcription factor | Zinc finger, C2H2-type, BTB/POZ-like |

| Lrrfip1 | ENSMUSG00000026305 | Leucine-rich repeat flightless-interacting protein 1 | nucleic acid binding, transcription factor | |

| Rplp2 | ENSMUSG00000025508 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2 | nucleic acid binding | WD40 repeat |

| Rps17 | ENSMUSG00000061787 | 40S ribosomal protein S17 | nucleic acid binding | |

| Nucleic acid binding or related | ||||

| Eif1 | ENSMUSG00000035530 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1b | ||

| Hdgf | ENSMUSG00000004897 | Hepatoma-derived growth factor | transcription factor, signaling molecule | PWWP domain |

| Hmgb3 | ENSMUSG00000015217 | High mobility group protein B3 | nucleic acid binding, transcription factor, signaling molecule | HMG box A DNA-binding domain |

| Junb | ENSMUSG00000052837 | Transcription factor jun-B | nucleic acid binding, transcription factor | Basic-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor |

| Not related to nucleic acid binding | ||||

| 1810009A15Rik | ENSMUSG00000071653 | |||

| A230050P20Rik | UPF0515 protein C19orf66 homolog | |||

| Arhgdia | ENSMUSG00000025132 | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 | enzyme modulator, signaling molecule | |

| Arhgdib | ENSMUSG00000030220 | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 2 | enzyme modulator, signaling molecule | |

| Capg | ENSMUSG00000056737 | Macrophage-capping protein | cytoskeletal protein, calcium-binding protein | Gelsolin |

| Cdv3 | ENSMUSG00000032803 | Protein CDV3 | ||

| Cfl1 | ENSMUSG00000056201 | Cofilin-1 | cytoskeletal protein | Actin-binding, cofilin/tropomyosin type |

| Fv4 | ENSMUSG00000075231 | MLV-related proviral Env polyprotein | Viral protein | |

| Hcls1 | ENSMUSG00000022831 | Hematopoietic lineage cell-specific protein | cytoskeletal protein, transcription factor | SH3 domain |

| Lcp1 | ENSMUSG00000021998 | lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 | cytoskeletal protein | Calponin-like actin-binding, Calcium-binding EF-hand |

| Lmna | ENSMUSG00000028063 | Prelamin-A/C; Lamin-A/C | cytoskeletal protein, structural protein | Intermediate filament tail domain |

| Ltv1 | ENSMUSG00000019814 | Protein LTV1 homolog | ||

| Pcnp | ENSMUSG00000071533 | PEST proteolytic signal-containing nuclear protein | ||

| Ptges3/p23 | ENSMUSG00000071072 | Prostaglandin E synthase 3 | chaperone | CS domain |

| Ranbp1 | ENSMUSG00000005732 | Ran-specific GTPase-activating protein | enzyme modulator | Pleckstrin homology-type |

| Set | ENSMUSG00000054766 | Protein SET | enzyme modulator, chaperone | |

| Tubb4b | ENSMUSG00000036752 | Tubulin beta-4B chain | cytoskeletal protein | |

| Txlna | ENSMUSG00000053841 | Alpha-taxilin | defense/immunity protein | Myosin-like coiled-coil protein |

| Vim | ENSMUSG00000026728 | Vimentin | cytoskeletal protein, structural protein | Intermediate filament protein |

Table II. Oligonucleotides for quantitative RT-PCR.

| target RNA | sense | sequence |

|---|---|---|

| firefly luciferase | forward | CCTTCCGCATAGAACTGCCT |

| reverse | GGTTGGTACTAGCAACGCAC | |

| Renilla luciferase | forward | GTTGTGCCACATATTGAGCC |

| reverse | CCAAACAAGCACCCCAATCATG | |

| CAT | forward | GGAATTCCGTATGGCAATGA |

| reverse | GATTGGCTGAGACGAAAAAC | |

| NDUFV1 | forward | GCCTCCAATTTGCAGGTAGCTAT |

| reverse | CACGCACCACAAACACATCA |

In addition we characterized the impact of LPS on the RNA binding activity of the 402 proteins that comprise the macrophage RNA interactome by applying the following cut-off criteria: [I] adjusted p value 2h LPS CL versus untreated CL <0.1, [II] detectable in both replicates, [III] log2 ratio >1 in both replicates, [IV] detectable in both replicates from untreated and LPS-treated cells. Our analyses uncovered three proteins as differentially bound in response to LPS: TTP, transcription factor JUN-B and ribosomal RNA processing-12 homolog (RRP12). A comparison of our data with that from LPS time-course experiments in RAW 264.7 macrophages, which addressed temporal dynamics of transcription, protein synthesis and secretion (20 min, 1, 2, 3 h LPS treatment) (58) revealed differential expression levels for two of the three proteins. This study showed that TTP and JUN-B were more abundant in LPS-treated cells, suggesting that the detected increase in RNA binding may be associated with elevated expression in LPS-induced macrophages. It is noteworthy that RRP12, which remained unchanged in expression level, is involved in ribosome biogenesis and was shown to interact with poly(A) in vitro (59).

P23 and HCLS1 Bind Directly to RNA

From the 19 macrophage-specific proteins that were designated as novel RBPs (Table I) based on our analysis, we chose two proteins to investigate their RNA-binding activity: P23, a HSP90 cochaperone (32), also known as PTGES3 (33); and HCLS1 or HS1, an adapter molecule with transcriptional activity that is important for myelopoiesis (34, 35).

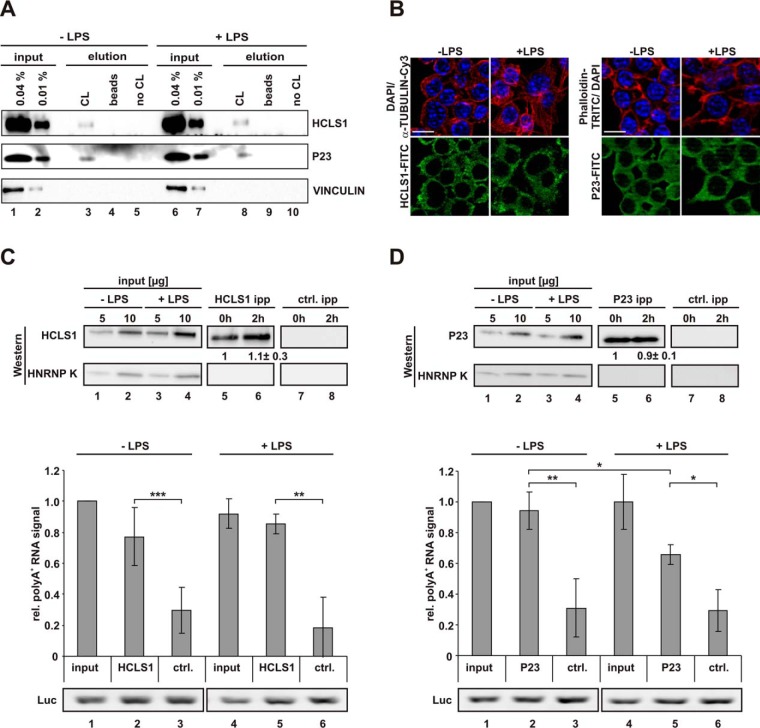

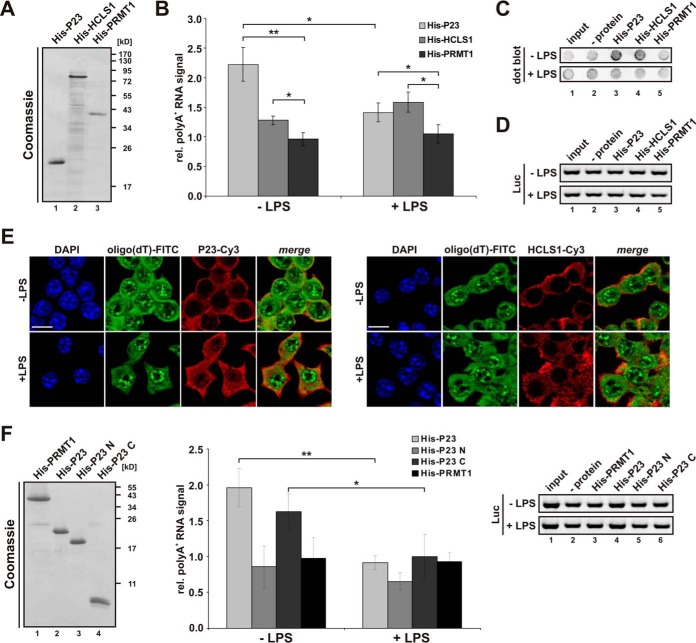

The presence of P23 and HCLS1 in eluates of oligo(dT) capture assays performed with untreated and LPS-induced macrophages was verified by Western blot (Fig. 5A). Both proteins are present in the input and the eluate of UV-irradiated samples (Fig. 5A, lanes 1–3 and 6–8), and absent from control eluates (Fig. 5A, lanes 4, 5 and 9, 10), whereas VINCULIN, tested as negative control, was not detected in any eluate. Importantly, consistent with the mass spectrometry analysis, LPS-induction did not affect the level of P23 and HCLS1, which are specifically detected in the eluate of the crosslinked reactions (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 8). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that both proteins are localized in the cytoplasm, at least at steady state (Fig. 5B). Therefore, we applied cytoplasmic extracts to address the interaction of endogenous P23 and HCLS1 with polyadenylated RNA in untreated macrophages and after LPS-induction. Quantification revealed that both proteins were immunoprecipitated at comparable levels independent of LPS treatment (Fig. 5C and 5D, upper panel).

Fig. 5.

Validation of RAW 264. 7 macrophage-specific RBPs. A, Samples obtained from RAW 264.7 cells, treated as in Fig. 1A and analyzed in Fig. 1B were used to detect HCLS1, P23 and VINCULIN. B, RAW 264.7 cells either left untreated or induced with LPS were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy to visualize endogenous proteins with specific antibodies as indicated, nuclei were stained with DAPI, F-actin with Phalloidin-TRITC. Scale bar: 10 μm. Specific HCLS1 (C) and P23 (D) immunoprecipitation with respective antibodies, a Luciferase antibody served as specificity control (ctrl. ipp). Representative Western blots for HCLS1 and P23, HNRNP K served as control (top), poly(A)+ RNA detection with a dot blot-based Biotin-Streptavidin assay (middle) and RT-PCR with primers for firefly luciferase (Luc) extraction control (bottom). Levels of immunoprecipitated HCLS1 and P23, shown beneath the respective blots, were quantified from three independent experiments (means ±s.d.). Coprecipitated poly(A)+ RNA was quantified from three independent experiments (* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001).

Specific coprecipitation of polyadenylated RNA was verified for both proteins, HCLS1 (Fig. 5C, middle panel) and P23 (Fig. 5D, middle panel) in a dot blot-based Biotin-Streptavidin assay, which utilizes biotinylated oligo(dT) hybridization to immobilized poly(A)+ RNA. Interestingly, a smaller proportion of poly(A)+ RNA was coprecipitated with P23 from cytoplasmic extracts of LPS-induced macrophages (Fig. 5D, middle panel, lanes 2 and 5). This was not because of RNA preparation differences as proven by equally detectable exogenously added firefly luciferase mRNA, shown in RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5D, lower panel).

To test whether the poly(A)+ RNA population binds directly to P23 and HCLS1, we purified macrophage mRNA and constructed expression vectors for both polypeptides. For initial in vitro interaction studies recombinant His-tagged proteins were purified from E. coli (Fig. 6A). His-P23 and His-HCLS1 immobilized on Ni-NTA agarose precipitated specifically poly(A)+ RNA from total RNA isolated from untreated and LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells, whereas His-PRMT1 did not (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, P23 precipitated more poly(A)+ RNA isolated from untreated macrophages than from LPS-induced macrophages (Fig. 6B, 6C), consistent with the coimmunoprecipitation of poly(A)+ RNA with endogenous P23 (Fig. 5D). Empty Ni-NTA beads (- protein in the dot blot) (Fig. 6C), which did not show poly(A)+ RNA binding were used for normalization (Fig. 6B). Differences in coprecipitation were not because of varying extraction efficiencies shown by RT-PCR analysis with primers for firefly luciferase extraction control (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of P23 and HCLS1 poly(A)+ RNA binding in vitro and in vivo. A, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of 2 μg His-P23, His-HCLS1 and His-PRMT1. B, His-P23, His-HCLS1 or His-PRMT1 were immobilized on Ni-NTA agarose and incubated with 50 μg total RNA purified from untreated or LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Coprecipitated poly(A)+ RNA from three independent experiments was detected with a dot blot-based Biotin-Streptavidin assay (* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01). C, Representative dot blot of coprecipitated poly(A)+ RNA shown in (B). D, RT-PCR analysis of samples described in (B) with primers for firefly luciferase (exogenous extraction control). E, RAW 264.7 cells either left untreated or induced with LPS were hybridized with oligo(dT) probe (FITC, green) for in situ hybridization. Immunostaining of endogenous P23 (Cy3, red) (left) and HCLS1 (Cy3, red) (right) was carried out using specific antibodies, staining of nuclei with DAPI. Scale bar: 10 μm. F, Left panel: Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of 1 μg His-PRMT1 and His-tagged P23 variants: P23 (aa 1–160), P23 N (aa 1–130), P23 C (aa 131–160). Middle panel: Proteins were immobilized on Ni-NTA agarose and incubated with 50 μg total RNA purified from untreated or LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Coprecipitated poly(A)+ RNA from three independent experiments was detected with a dot blot-based Biotin-Streptavidin assay (* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01). Right panel: RT-PCR analysis with primers for firefly luciferase.

To validate the interaction of HCLS1 and P23 with poly(A)+ RNA observed in the immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 5C and 5D) and with recombinant protein (Fig. 6B) in vivo in LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells, we applied immunofluorescence and FISH. Analysis of untreated and LPS-induced cells using a fluorescent oligo(dT) probe revealed that LPS diminishes the colocalization of P23 with poly(A)+ RNA in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6E, left panel), but not that of HCLS1 and poly(A)+ RNA (Fig. 6E, right panel).

Because differential poly(A)+ RNA-interaction could be detected in vitro and in vivo for P23, we wanted to characterize its RNA binding domains. Interestingly, P23 contains an unstructured C-terminal tail (aa 131–160) (60, 61). To specify poly(A)+ RNA binding domains, we constructed and expressed P23 and deletion variants (Fig. 6F, left panel), which were immobilized on Ni-NTA agarose. Consistent with Fig. 6B, binding of poly(A)+ RNA from LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells to His-P23 was reduced (Fig. 6F, middle panel). Interestingly, the 30 aa C-terminal part (His-P23 C) confers the poly(A)+ RNA interaction, which declines as observed for full length P23 (Fig. 6F, middle panel). This was not because of varying extraction efficiencies (Fig. 6F, right panel).

These results suggest that the two proteins P23 and HCLS1, which were so far not classified as related to nucleic acid binding, exhibit RNA-binding activity.

DISCUSSION

Employing endogenous poly(A)+ interactome capture we present here the first comprehensive analysis of RNA-binding proteins in murine macrophages. Our analysis identified 402 RBPs, referred to here as macrophage RNA interactome, including 91 proteins not previously annotated as RBPs. A comparison with published RNA interactomes (29–31) classified 32 RBPs as uniquely identified in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Table I). 19 proteins of that group, which lack RNA-related functional annotations, could be ranked as novel macrophage RBPs (Table I).

Panther protein class annotation (56, 57) of these newly identified RBPs revealed an over-representation of cytoskeletal proteins (Fig. 4C, Table I). Importantly, cytoskeletal proteins are involved in chemotactic and phagocytic macrophage functions, which require extensive actin cytoskeleton remodeling (62). From the seven cytoskeletal protein genes (Capg, Cfl1, Hcls1, Lcp1, Vim, Tubb4b, and Lmna) assigned by Panther classification we chose an interesting candidate, Hcls1. The encoded protein not only contributes to cytoskeletal reorganization, but in complex with other factors (35) also to transcription activation in the LPS-induced monocyte to macrophage transition (63, 64). We found that the murine RAW 264.7 macrophage LPS-response does not affect HCLS1 expression (Fig. 5A), consistent with mass spectrometry analyses of LPS-induced human THP-1 monocytes (64). Notably, HCLS1, which is localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5B) showed poly(A)+-RNA binding activity in cytoplasmic extracts (Fig. 5C) and as recombinant protein (Fig. 6B) as well as in RAW 264.7 cells (Fig. 6E, right panel) that was not influenced by LPS-induction. The identification of HCLS1 as an RBP now expands the view of how HCLS1 mediates the cell fate in macrophages. HCLS1 is exclusively expressed in hematopoietic cells, i.e. lymphoid, myeloid and erythroid cell lines as well as circulating lymphocytes, granulocytes and macrophages. Human HCLS1 (34) and its murine orthologue (65) are highly homologous (87% identity). The multidomain protein HCLS1 bears an N-terminal acidic domain (NTA) that directly binds and activates the actin-related protein (ARP) 2/3 complex, thereby promoting actin polymerization (66). The NTA is followed by a helix-turn-helix motif. Interestingly, a helix-turn-helix motif contributes to RNA binding of ROQUIN (67–69), which implicates a candidate for the RNA-interaction in HCLS1. A coiled-coil region represents the main F-actin binding site and functions synergistically with the helix-turn-helix motif (70–72). Interestingly, HCLS1 knock down in CD34+ cells led to an increase in F-actin expression and a resulting disturbed F-actin organization (35). Furthermore, besides a central proline-rich region HCLS1 displays a C-terminal SH3 domain (34), which initiates receptor-coupled tyrosine kinase activation (72). Tyrosine kinases SYK, LYN and LCK and the adaptor protein GRB2 phosphorylate and activate the protein (73–78). In platelets casein kinase 2 catalyzes HCLS1 threonine and serine phosphorylation (79). A comparison with the phospho-proteome of LPS-treated murine bone marrow derived macrophages (80) revealed that LPS treatment results in diminished HCLS1 phosphorylation, and it might be assumed that regulated phosphorylation causes differential interaction with individual mRNAs (27).

LPS-mediated macrophage activation not only involves cytoskeletal remodeling, but requires HSP90 activity that is essential for stabilization and maturation of protein factors involved in NFκB activation and inflammation (81–83). Among the novel RBPs we identified the HSP90 cochaperone P23 (32) or cytoplasmic PTGES3 (33), which was therefore chosen for further analysis. LPS treatment was shown to elevate PTGES3 activity in peritoneal macrophages (84). Along with HSP90, P23 interacts with AGO2, stabilizes its open conformation and facilitates structural changes that promote RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) loading (85).

During apoptosis P23 is cleaved by CASPASE-3 and 8 (86). Interestingly, we discovered that LPS-induction of RAW 264.7 macrophages leads to miR-155-mediated CASPASE-3 down-regulation and decelerated apoptosis, thereby sustaining macrophage activity (87). This is in agreement with a role of P23 in preventing ER-stress-induced apoptosis (88, 89).

Notably, after LPS-induction P23 immunoprecipitated from cytoplasmic extracts (Fig. 5D) as well as recombinant P23 exhibited reduced poly(A)+-RNA-binding activity (Fig. 6B), consistent with declining P23- poly(A)+-RNA colocalization in RAW 264.7 cells (Fig. 6E, left panel). This is not because of altered P23 expression in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages (Fig. 5A) or changes in the pool of total RNA and poly(A)+ RNA captured by oligo(dT) after LPS treatment (Fig. 1D).

P23 contains a compact β-strand CS domain (CHORD-containing proteins and SGT1), which provides a HSP90 binding surface. The unstructured C-terminal tail (30 aa) of P23 is necessary for optimal chaperone activity, but not for HSP90 interaction (60, 61). That C-terminal tail of P23 mediates poly(A)+-RNA interaction (Fig. 6F, middle panel). This is in agreement with the reported function of disordered protein regions as RNA chaperones (90) and the contribution of the unstructured C-terminal tail of HIV-1 VIF to RNA binding (91). Strikingly, the identification of P23/PTGES3 as a new RBP adds that protein to the growing family of metabolic enzymes that emerged to exhibit RNA binding activity (92, 93), providing potential functions in post-transcriptional gene regulation that need to be explored.

Therefore future studies will focus on the identification and functional analysis of polyadenylated RNAs that are bound differentially in response to LPS and the potential impact of post-translational modifications on RNA-binding of P23.

In summary, our study expands the mammalian RBP repertoire, and identified specific macrophage RBPs that respond to LPS. These RBPs are prime candidates for the post-transcriptional regulation and execution of LPS-induced TLR4 signaling pathways and the innate immune response. Information about underlying molecular mechanisms of RBP functions will advance our understanding of their role in inflammatory response modulation and provide us with knowledge about their potential as therapeutic targets to prevent systemic inflammation and sepsis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yalin Liao for critical reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge technical support by the ACRF Biomolecular Resource Facility at JCSMR and the EMBL Proteomics Core Facility.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Biochemical experiments were performed by A.L. (Figures 1 and 5A), I.S.N.-d.V. (Figures 5 and Figure 6, except 5A and 5C–5D, upper panel) and N.S. (Figure 5C–5D, upper panel). A.L. and I.S.N.-d.V. analyzed experimental data. K.E., S.F. and J.K. executed mass spectrometry experiments, analyzed the data for Figure 2A and supplemental Table S1 and S2; and deposited mass spec data in ProteomeXchange. S.K.A. and T.P. performed high-throughput sequencing experiments and data analysis presented in Figure 1F and G. A.L. analyzed the RNA interactome as shown in Figures 2B–2D, 3, and 4B and 4C. B.U. essentially contributed to RNA interactome analysis (Figures 3 and 4) and prepared the data for Figure 4A. A.C. and M.W.H. made substantial contribution to the conceptual design of the study. G.M. contributed to the development of the project. D.H.O. and A.O.-L. designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

* This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (OS 290/6–1) to A.O.-L.; and in part by grants from the DFG to I.S.N.-d.V. (NA 1273/1-1) and from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (#1045417) to T.P. and M.W.H. Furthermore, M.W.H. acknowledges support by the ERC Advanced Grant ERC-2011-ADG_20110310.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- TLR4

- Toll-like receptor 4

- ARE-BP

- AU-rich element-binding protein

- LC-MS/MS

- Liquid chromatography-tandem MS

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharides

- MAPKs

- mitogen activated protein kinases

- RBP

- RNA-binding protein

- NFκB

- Nuclear factor kappa B

- PTGES3

- Prostaglandin E synthase 3

- HCLS1

- Hematopoietic cell-specific LYN substrate 1

- GO

- Gene Ontology.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hotchkiss R. S., and Karl I. E. (2003) The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl. J. Med. 348, 138–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zanotti S., Kumar A., and Kumar A. (2002) Cytokine modulation in sepsis and septic shock. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 11, 1061–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reynier F., de Vos A. F., Hoogerwerf J. J., Bresser P., van der Zee J. S., Paye M., Pachot A., Mougin B., and van der Poll T. (2012) Gene expression profiles in alveolar macrophages induced by lipopolysaccharide in humans. Mol. Med. 18, 1303–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rutledge H. R., Jiang W., Yang J., Warg L. A., Schwartz D. A., Pisetsky D. S., and Yang I. V. (2012) Gene expression profiles of RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated with preparations of LPS differing in isolation and purity. Innate Immunity 18, 80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Medzhitov R., and Horng T. (2009) Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 692–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smale S. T. (2012) Transcriptional regulation in the innate immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 51–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carpenter S., Ricci E. P., Mercier B. C., Moore M. J., and Fitzgerald K. A. (2014) Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 361–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kafasla P., Skliris A., and Kontoyiannis D. L. (2014) Post-transcriptional coordination of immunological responses by RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Immunol. 15, 492–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwerk J., and Savan R. (2015) Translating the untranslated region. J. Immunol. 195, 2963–2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Caput D., Beutler B., Hartog K., Thayer R., Brown-Shimer S., and Cerami A. (1986) Identification of a common nucleotide sequence in the 3′-untranslated region of mRNA molecules specifying inflammatory mediators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 1670–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beisang D., and Bohjanen P. R. (2012) Perspectives on the ARE as it turns 25 years old. Wiley Interdisciplinary Rev. RNA 3, 719–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ivanov P., and Anderson P. (2013) Post-transcriptional regulatory networks in immunity. Immunol. Rev. 253, 253–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Piecyk M., Wax S., Beck A. R., Kedersha N., Gupta M., Maritim B., Chen S., Gueydan C., Kruys V., Streuli M., and Anderson P. (2000) TIA-1 is a translational silencer that selectively regulates the expression of TNF-alpha. EMBO J. 19, 4154–4163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garnon J., Lachance C., Di Marco S., Hel Z., Marion D., Ruiz M. C., Newkirk M. M., Khandjian E. W., and Radzioch D. (2005) Fragile X-related protein FXR1P regulates proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor expression at the post-transcriptional level. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5750–5763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mukhopadhyay D., Houchen C. W., Kennedy S., Dieckgraefe B. K., and Anant S. (2003) Coupled mRNA stabilization and translational silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 by a novel RNA binding protein, CUGBP2. Mol. Cell 11, 113–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Briata P., Chen C. Y., Giovarelli M., Pasero M., Trabucchi M., Ramos A., and Gherzi R. (2011) KSRP, many functions for a single protein. Frontiers Biosci. 16, 1787–1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carballo E., Lai W. S., and Blackshear P. J. (1998) Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science 281, 1001–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stoecklin G., Colombi M., Raineri I., Leuenberger S., Mallaun M., Schmidlin M., Gross B., Lu M., Kitamura T., and Moroni C. (2002) Functional cloning of BRF1, a regulator of ARE-dependent mRNA turnover. EMBO J. 21, 4709–4718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen C. Y., Gherzi R., Andersen J. S., Gaietta G., Jurchott K., Royer H. D., Mann M., and Karin M. (2000) Nucleolin and YB-1 are required for JNK-mediated interleukin-2 mRNA stabilization during T-cell activation. Genes Develop. 14, 1236–1248 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fan X. C., and Steitz J. A. (1998) Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J. 17, 3448–3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peng S. S., Chen C. Y., Xu N., and Shyu A. B. (1998) RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 17, 3461–3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katsanou V., Papadaki O., Milatos S., Blackshear P. J., Anderson P., Kollias G., and Kontoyiannis D. L. (2005) HuR as a negative posttranscriptional modulator in inflammation. Mol. Cell 19, 777–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tiedje C., Ronkina N., Tehrani M., Dhamija S., Laass K., Holtmann H., Kotlyarov A., and Gaestel M. (2012) The p38/MK2-driven exchange between tristetraprolin and HuR regulates AU-rich element-dependent translation. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yiakouvaki A., Dimitriou M., Karakasiliotis I., Eftychi C., Theocharis S., and Kontoyiannis D. L. (2012) Myeloid cell expression of the RNA-binding protein HuR protects mice from pathologic inflammation and colorectal carcinogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 48–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sarkar S., Han J., Sinsimer K. S., Liao B., Foster R. L., Brewer G., and Pestka S. (2011) RNA-binding protein AUF1 regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced IL10 expression by activating IkappaB kinase complex in monocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 602–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu J. Y., Sadri N., and Schneider R. J. (2006) Endotoxic shock in AUF1 knockout mice mediated by failure to degrade proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs. Genes Develop. 20, 3174–3184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liepelt A., Mossanen J. C., Denecke B., Heymann F., De Santis R., Tacke F., Marx G., Ostareck D. H., and Ostareck-Lederer A. (2014) Translation control of TAK1 mRNA by hnRNP K modulates LPS-induced macrophage activation. Rna 20, 899–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castello A., Horos R., Strein C., Fischer B., Eichelbaum K., Steinmetz L. M., Krijgsveld J., and Hentze M. W. (2013) System-wide identification of RNA-binding proteins by interactome capture. Nat. Protocols 8, 491–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Castello A., Fischer B., Eichelbaum K., Horos R., Beckmann B. M., Strein C., Davey N. E., Humphreys D. T., Preiss T., Steinmetz L. M., Krijgsveld J., and Hentze M. W. (2012) Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149, 1393–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baltz A. G., Munschauer M., Schwanhausser B., Vasile A., Murakawa Y., Schueler M., Youngs N., Penfold-Brown D., Drew K., Milek M., Wyler E., Bonneau R., Selbach M., Dieterich C., and Landthaler M. (2012) The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol. Cell 46, 674–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kwon S. C., Yi H., Eichelbaum K., Fohr S., Fischer B., You K. T., Castello A., Krijgsveld J., Hentze M. W., and Kim V. N. (2013) The RNA-binding protein repertoire of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Structural Mol. Biol. 20, 1122–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson J. L., Beito T. G., Krco C. J., and Toft D. O. (1994) Characterization of a novel 23-kilodalton protein of unactive progesterone receptor complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 1956–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tanioka T., Nakatani Y., Semmyo N., Murakami M., and Kudo I. (2000) Molecular identification of cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase that is functionally coupled with cyclooxygenase-1 in immediate prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32775–32782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kitamura D., Kaneko H., Miyagoe Y., Ariyasu T., and Watanabe T. (1989) Isolation and characterization of a novel human gene expressed specifically in the cells of hematopoietic lineage. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 9367–9379 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Skokowa J., Klimiankou M., Klimenkova O., Lan D., Gupta K., Hussein K., Carrizosa E., Kusnetsova I., Li Z., Sustmann C., Ganser A., Zeidler C., Kreipe H. H., Burkhardt J., Grosschedl R., and Welte K. (2012) Interactions among HCLS1, HAX1 and LEF-1 proteins are essential for G-CSF-triggered granulopoiesis. Nat. Med. 18, 1550–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thermann R., and Hentze M. W. (2007) Drosophila miR2 induces pseudo-polysomes and inhibits translation initiation. Nature 447, 875–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stripecke R., and Hentze M. W. (1992) Bacteriophage and spliceosomal proteins function as position-dependent cis/trans repressors of mRNA translation in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 5555–5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang X., and Cheng X. (2003) Structure of the predominant protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT1 and analysis of its binding to substrate peptides. Structure 11, 509–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cox J., and Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nature Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cox J., Neuhauser N., Michalski A., Scheltema R. A., Olsen J. V., and Mann M. (2011) Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J. Proteome Res. 10, 1794–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gentleman R. C., Carey V. J., Bates D. M., Bolstad B., Dettling M., Dudoit S., Ellis B., Gautier L., Ge Y., Gentry J., Hornik K., Hothorn T., Huber W., Iacus S., Irizarry R., Leisch F., Li C., Maechler M., Rossini A. J., Sawitzki G., Smith C., Smyth G., Tierney L., Yang J. Y., and Zhang J. (2004) Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ritchie M. E., Phipson B., Wu D., Hu Y., Law C. W., Shi W., and Smyth G. K. (2015) limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vizcaino J. A., Deutsch E. W., Wang R., Csordas A., Reisinger F., Rios D., Dianes J. A., Sun Z., Farrah T., Bandeira N., Binz P. A., Xenarios I., Eisenacher M., Mayer G., Gatto L., Campos A., Chalkley R. J., Kraus H. J., Albar J. P., Martinez-Bartolome S., Apweiler R., Omenn G. S., Martens L., Jones A. R., and Hermjakob H. (2014) ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 223–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang da W., Sherman B. T., and Lempicki R. A. (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protocols 4, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang da W., Sherman B. T., and Lempicki R. A. (2009) Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Naarmann I. S., Harnisch C., Flach N., Kremmer E., Kuhn H., Ostareck D. H., and Ostareck-Lederer A. (2008) mRNA silencing in human erythroid cell maturation: heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K controls the expression of its regulator c-Src. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18461–18472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Livak K. J., and Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. de Vries S., Naarmann-de Vries I. S., Urlaub H., Lue H., Bernhagen J., Ostareck D. H., and Ostareck-Lederer A. (2013) Identification of DEAD-box RNA helicase 6 (DDX6) as a cellular modulator of vascular endothelial growth factor expression under hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 5815–5827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schroeder A., Mueller O., Stocker S., Salowsky R., Leiber M., Gassmann M., Lightfoot S., Menzel W., Granzow M., and Ragg T. (2006) The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol. Biol. 7, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Archer S. K., Shirokikh N. E., and Preiss T. (2015) Probe-directed degradation (PDD) for flexible removal of unwanted cDNA sequences from RNA-Seq libraries. Current Protocols Human Genetics 85, 11 15 11–11 15 36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Naarmann I. S., Harnisch C., Muller-Newen G., Urlaub H., Ostareck-Lederer A., and Ostareck D. H. (2010) DDX6 recruits translational silenced human reticulocyte 15-lipoxygenase mRNA to RNP granules. Rna 16, 2189–2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Staudacher J. J., Naarmann-de Vries I. S., Ujvari S. J., Klinger B., Kasim M., Benko E., Ostareck-Lederer A., Ostareck D. H., Bondke Persson A., Lorenzen S., Meier J. C., Bluthgen N., Persson P. B., Henrion-Caude A., Mrowka R., and Fahling M. (2015) Hypoxia-induced gene expression results from selective mRNA partitioning to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 3219–3236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ostareck-Lederer A., Ostareck D. H., Rucknagel K. P., Schierhorn A., Moritz B., Huttelmaier S., Flach N., Handoko L., and Wahle E. (2006) Asymmetric arginine dimethylation of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K by protein-arginine methyltransferase 1 inhibits its interaction with c-Src. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11115–11125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Adolph D., Flach N., Mueller K., Ostareck D. H., and Ostareck-Lederer A. (2007) Deciphering the cross talk between hnRNP K and c-Src: the c-Src activation domain in hnRNP K is distinct from a second interaction site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 1758–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mitchell S. F., Jain S., She M., and Parker R. (2013) Global analysis of yeast mRNPs. Nat. Structural Mol. Biol. 20, 127–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Thomas P. D., Campbell M. J., Kejariwal A., Mi H., Karlak B., Daverman R., Diemer K., Muruganujan A., and Narechania A. (2003) PANTHER: a library of protein families and subfamilies indexed by function. Genome Res. 13, 2129–2141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mi H., Muruganujan A., Casagrande J. T., and Thomas P. D. (2013) Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat. Protocols 8, 1551–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Eichelbaum K., and Krijgsveld J. (2014) Rapid temporal dynamics of transcription, protein synthesis, and secretion during macrophage activation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 792–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Oeffinger M., Dlakic M., and Tollervey D. (2004) A pre-ribosome-associated HEAT-repeat protein is required for export of both ribosomal subunits. Genes Develop. 18, 196–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weaver A. J., Sullivan W. P., Felts S. J., Owen B. A., and Toft D. O. (2000) Crystal structure and activity of human p23, a heat shock protein 90 co-chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23045–23052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Weikl T., Abelmann K., and Buchner J. (1999) An unstructured C-terminal region of the Hsp90 co-chaperone p23 is important for its chaperone function. J. Mol. Biol. 293, 685–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rougerie P., Miskolci V., and Cox D. (2013) Generation of membrane structures during phagocytosis and chemotaxis of macrophages: role and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Immunol. Rev. 256, 222–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shin J. W., Suzuki T., Ninomiya N., Kishima M., Hasegawa Y., Kubosaki A., Yabukami H., Hayashizaki Y., and Suzuki H. (2012) Establishment of single-cell screening system for the rapid identification of transcriptional modulators involved in direct cell reprogramming. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Billing A. M., Fack F., Turner J. D., and Muller C. P. (2011) Cortisol is a potent modulator of lipopolysaccharide-induced interferon signaling in macrophages. Innate Immunity 17, 302–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kitamura D., Kaneko H., Taniuchi I., Akagi K., Yamamura K., and Watanabe T. (1995) Molecular cloning and characterization of mouse HS1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Communications 208, 1137–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Uruno T., Zhang P., Liu J., Hao J. J., and Zhan X. (2003) Haematopoietic lineage cell-specific protein 1 (HS1) promotes actin-related protein (Arp) 2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerization. Biochem. J. 371, 485–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Janowski R., Heinz G. A., Schlundt A., Wommelsdorf N., Brenner S., Gruber A. R., Blank M., Buch T., Buhmann R., Zavolan M., Niessing D., Heissmeyer V., and Sattler M. (2016) Roquin recognizes a non-canonical hexaloop structure in the 3′-UTR of Ox40. Nat. Communications 7, 11032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schlundt A., Heinz G. A., Janowski R., Geerlof A., Stehle R., Heissmeyer V., Niessing D., and Sattler M. (2014) Structural basis for RNA recognition in roquin-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation. Nat. Structural Mol. Biol. 21, 671–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schuetz A., Murakawa Y., Rosenbaum E., Landthaler M., and Heinemann U. (2014) Roquin binding to target mRNAs involves a winged helix-turn-helix motif. Nat. Communications 5, 5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hao J. J., Zhu J., Zhou K., Smith N., and Zhan X. (2005) The coiled-coil domain is required for HS1 to bind to F-actin and activate Arp2/3 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37988–37994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. van Rossum A. G., Schuuring-Scholtes E., van Buuren-van Seggelen V., Kluin P. M., and Schuuring E. (2005) Comparative genome analysis of cortactin and HS1: the significance of the F-actin binding repeat domain. BMC Genomics 6, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Huang Y., and Burkhardt J. K. (2007) T-cell-receptor-dependent actin regulatory mechanisms. J. Cell Sci. 120, 723–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hao J. J., Carey G. B., and Zhan X. (2004) Syk-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation is required for the association of hematopoietic lineage cell-specific protein 1 with lipid rafts and B cell antigen receptor signalosome complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33413–33420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Takemoto Y., Furuta M., Sato M., Findell P. R., Ramble W., and Hashimoto Y. (1998) Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) association with hemopoietic specific protein 1: linkage between Lck and Grb2. J. Immunol. 161, 625–630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ingley E., Sarna M. K., Beaumont J. G., Tilbrook P. A., Tsai S., Takemoto Y., Williams J. H., and Klinken S. P. (2000) HS1 interacts with Lyn and is critical for erythropoietin-induced differentiation of erythroid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7887–7893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yamanashi Y., Okada M., Semba T., Yamori T., Umemori H., Tsunasawa S., Toyoshima K., Kitamura D., Watanabe T., and Yamamoto T. (1993) Identification of HS1 protein as a major substrate of protein-tyrosine kinase(s) upon B-cell antigen receptor-mediated signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3631–3635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Brunati A. M., Deana R., Folda A., Massimino M. L., Marin O., Ledro S., Pinna L. A., and Donella-Deana A. (2005) Thrombin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of HS1 in human platelets is sequentially catalyzed by Syk and Lyn tyrosine kinases and associated with the cellular migration of the protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21029–21035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kahner B. N., Dorsam R. T., Mada S. R., Kim S., Stalker T. J., Brass L. F., Daniel J. L., Kitamura D., and Kunapuli S. P. (2007) Hematopoietic lineage cell specific protein 1 (HS1) is a functionally important signaling molecule in platelet activation. Blood 110, 2449–2456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ruzzene M., Brunati A. M., Sarno S., Marin O., Donella-Deana A., and Pinna L. A. (2000) Ser/Thr phosphorylation of hematopoietic specific protein 1 (HS1): implication of protein kinase CK2. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 3065–3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Weintz G., Olsen J. V., Fruhauf K., Niedzielska M., Amit I., Jantsch J., Mages J., Frech C., Dolken L., Mann M., and Lang R. (2010) The phosphoproteome of toll-like receptor-activated macrophages. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chatterjee A., Dimitropoulou C., Drakopanayiotakis F., Antonova G., Snead C., Cannon J., Venema R. C., and Catravas J. D. (2007) Heat shock protein 90 inhibitors prolong survival, attenuate inflammation, and reduce lung injury in murine sepsis. Am. J. Respiratory Critical Care Med. 176, 667–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chatterjee A., Snead C., Yetik-Anacak G., Antonova G., Zeng J., and Catravas J. D. (2008) Heat shock protein 90 inhibitors attenuate LPS-induced endothelial hyperpermeability. Am. J. Physiol. 294, L755–L763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Thangjam G. S., Dimitropoulou C., Joshi A. D., Barabutis N., Shaw M. C., Kovalenkov Y., Wallace C. M., Fulton D. J., Patel V., and Catravas J. D. (2014) Novel mechanism of attenuation of LPS-induced NF-kappaB activation by the heat shock protein 90 inhibitor, 17-N-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin, in human lung microvascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Respiratory Cell Mol. Biol. 50, 942–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Naraba H., Murakami M., Matsumoto H., Shimbara S., Ueno A., Kudo I., and Oh-ishi S. (1998) Segregated coupling of phospholipases A2, cyclooxygenases, and terminal prostanoid synthases in different phases of prostanoid biosynthesis in rat peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 160, 2974–2982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pare J. M., LaPointe P., and Hobman T. C. (2013) Hsp90 cochaperones p23 and FKBP4 physically interact with hAgo2 and activate RNA interference-mediated silencing in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 2303–2310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mollerup J., and Berchtold M. W. (2005) The co-chaperone p23 is degraded by caspases and the proteasome during apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 579, 4187–4192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. De Santis R., Liepelt A., Mossanen J. C., Dueck A., Simons N., Mohs A., Trautwein C., Meister G., Marx G., Ostareck-Lederer A., and Ostareck D. H. (2016) miR-155 targets Caspase-3 mRNA in activated macrophages. RNA Biol. 13, 43–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Poksay K. S., Banwait S., Crippen D., Mao X., Bredesen D. E., and Rao R. V. (2012) The small chaperone protein p23 and its cleaved product p19 in cellular stress. J. Mol. Neurosci. 46, 303–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rao R. V., Niazi K., Mollahan P., Mao X., Crippen D., Poksay K. S., Chen S., and Bredesen D. E. (2006) Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell-death program: a novel HSP90-independent role for the small chaperone protein p23. Cell Death Differentiation 13, 415–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Semrad K. Proteins with RNA chaperone activity: a world of diverse proteins with a common task-impediment of RNA misfolding. Biochem. Res. Int. 2011:532908, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sleiman D., Bernacchi S., Xavier Guerrero S., Brachet F., Larue V., Paillart J. C., and Tisne C. (2014) Characterization of RNA binding and chaperoning activities of HIV-1 Vif protein. Importance of the C-terminal unstructured tail. RNA Biol. 11, 906–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Castello A., Hentze M. W., and Preiss T. (2015) Metabolic Enzymes Enjoying New Partnerships as RNA-Binding Proteins. Trends Endocrinol. Metabolism: TEM 26, 746–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hentze M. W., and Preiss T. (2010) The REM phase of gene regulation. Trends in Biochem. Sci. 35, 423–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.