Abstract

Chameleon teeth develop as individual structures at a distance from the developing jaw bone during the pre‐hatching period and also partially during the post‐hatching period. However, in the adult, all teeth are fused together and tightly attached to the jaw bone by mineralized attachment tissue to form one functional unit. Tooth to bone as well as tooth to tooth attachments are so firm that if injury to the oral cavity occurs, several neighbouring teeth and pieces of jaw can be broken off. We analysed age‐related changes in chameleon acrodont dentition, where ankylosis represents a physiological condition, whereas in mammals, ankylosis only occurs in a pathological context. The changes in hard‐tissue morphology and mineral composition leading to this fusion were analysed. For this purpose, the lower jaws of chameleons were investigated using X‐ray micro‐computed tomography, laser‐induced breakdown spectroscopy and microprobe analysis. For a long time, the dental pulp cavity remained connected with neighbouring teeth and also to the underlying bone marrow cavity. Then, a progressive filling of the dental pulp cavity by a mineralized matrix occurred, and a complex network of non‐mineralized channels remained. The size of these unmineralized channels progressively decreased until they completely disappeared, and the dental pulp cavity was filled by a mineralized matrix over time. Moreover, the distribution of calcium, phosphorus and magnesium showed distinct patterns in the different regions of the tooth–bone interface, with a significant progression of mineralization in dentin as well as in the supporting bone. In conclusion, tooth–bone fusion in chameleons results from an enhanced production of mineralized tissue during post‐hatching development. Uncovering the developmental processes underlying these outcomes and performing comparative studies is necessary to better understand physiological ankylosis; for that purpose, the chameleon can serve as a useful model species.

Keywords: acrodont dentition, laser‐induced breakdown spectroscopy, micro‐computed tomography, reptiles

Introduction

Reptiles show variability in tooth morphology (Edmund, 1969) as well as in the microscopic anatomy of tooth attachment (Osborn, 1984; Gaengler, 1991; Gaengler & Metzler, 1992; Zaher & Rieppel, 1999). Ancestral reptiles generally had teeth inserted in shallow sockets (protothecodont attachment) (Edmund, 1969). Some lizards (e.g. agamas, chameleons) have teeth ankylosed to the crest of the tooth‐bearing bone (acrodont teeth) (Edmund, 1969; Zaher & Rieppel, 1999). However, most lizards and snakes have teeth ankylosed to the inner side of the high labial wall (pleurodont attachment) (Gaengler, 1991; Gaengler & Metzler, 1992). In contrast, the teeth of mammals, including humans, have relatively long cylindrical roots connected by periodontal tissues with a deep bony socket (thecodont attachment). Thecodont attachment is also found in the extant archosarian lineage of reptiles. The morphology of caiman periodontal attachments represents an intermediate condition between the ankylosis‐type of attachment of Lepidosaurian reptiles and the mammalian periodontium (McIntosh et al. 2002).

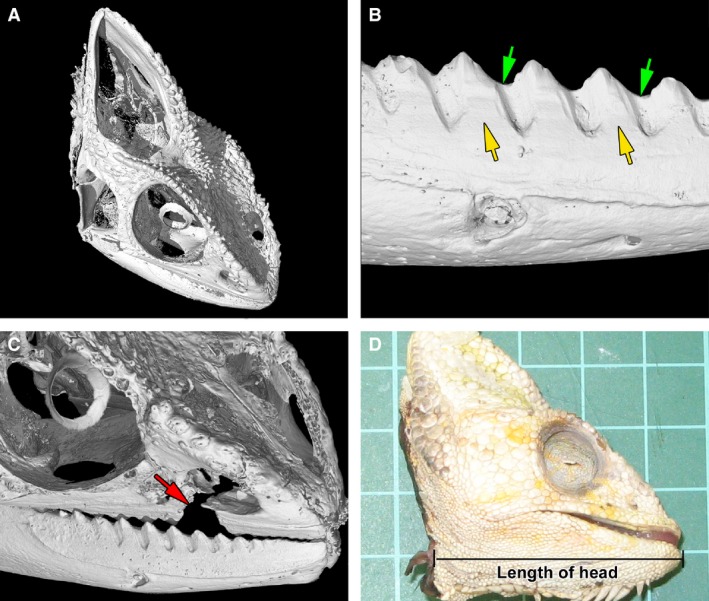

In the chameleon, there is only one generation of teeth, and all teeth attach firmly to the underlying bone by mineralized attachment tissue (Fig. 1A,B) (Buchtova et al. 2013). Moreover, the adult teeth are attached to each other to form saw‐like dentition along the jaw (Fig. 1B,C). Whereas ankylosis represents a pathological condition in humans and leads to serious damage, such as root and surrounding bone tissue resorption (Andersson & Malmgren, 1999), acrodontal ankylosis in the chameleon is a normal and physiological state. Moreover, in juvenile chameleons, the gingiva recedes from the area of the tooth–bone interface and naked bone is revealed (Buchtova et al. 2013) without any obvious health troubles, unlike in humans.

Figure 1.

Skull morphology in the chameleon. (A) The microCT scanning allowed a visualization of individual skull elements. (B) Detailed view of the tooth–bone fusion area (yellow arrow) as well as the firm adhesion between neighbouring teeth (green arrow). (C) Tooth loss was linked with the fracture of maxillary bone (red arrow). (D) The head length was measured from the most distal tip of the mandible to the mandibular angle.

Interestingly, tooth to bone attachment is so firm in chameleons that if injury to the oral cavity occurs, teeth are not lost, as would happen in mammals. Rather, a piece of the jaw with several neighbouring teeth is broken off (Fig. 1C). Such large injuries to the jaw can happen during incautious feeding with hard metal tools or sexual competition, as male chameleons are known to bite each other during conflict (Stuart‐Fox & Whiting, 2005). Moreover, non‐receptive females can be bite‐aggressive toward the male (Burrage, 1973; Stuart‐Fox & Whiting, 2005).

Based on previous findings, we aimed to analyse age‐related changes in hard‐tissue morphology with a focus on the tooth–bone fusion area during post‐hatching stages in the chameleon. First, micro‐computed tomography (microCT) imaging was used to evaluate how the fusion between tooth and jaw, as well as between neighbouring teeth, occurs during development. Next, the possible differences in mineral content accompanying these developmental processes were analysed. Calcium and phosphorus are the main matrix elements of hard tissues. In human teeth, enamel contains approximately 96% calcium apatite, as either hydroxyapatite [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2] or fluorapatite [Ca10(PO4)6F2] (Young, 1974; Lucas, 1979; Ten Cate, 1994). Magnesium is mostly present during bone and tooth formation, where it regulates calcification (Althoff et al. 1982; Bigi et al. 1992). For these reasons, the changes in composition of these three elements (calcium, phosphorus and magnesium) were analysed in tooth, jaw bone and the fusion areas between tooth and bone using laser‐induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) and quantitatively with microprobe analysis at post‐hatching stages in the chameleon. In reptiles, LIBS has been previously used only for the analysis of mineral content in snake vertebrae (Galiova et al. 2010), and mineral content in teeth has not been evaluated using this method until now. We hypothesized that mineral distribution in post‐hatching chameleons might be different than in humans and other previously studied mammalian species, where ankylosis leads to demineralization of the underlying bone.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animals were obtained from the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences (Brno, Czech Republic). To demonstrate developmental changes in tooth–bone fusion area and bone morphology, four pre‐hatching stages (13, 14, 15 and 16 weeks of incubation) were collected. For mineral content analyses, juvenile and adult post‐hatching animals were selected and their lower jaw size measured (Fig. 1D) in a rostro‐caudal direction (juvenile 1: 1.4 cm, juvenile 2: 1.9 cm, adult 1: 3.6 cm, adult 2: 4.0 cm). All of the animals died due to non‐skeleton‐related diseases. All procedures were conducted following a protocol approved by the Laboratory Animal Science Committee of the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences – Brno (Czech Republic).

Histological analysis

The heads of embryonic and juvenile chameleons were fixed in 4% formaldehyde overnight, and the specimens were decalcified in 5% EDTA with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. The time of the decalcification varied from 2 weeks to 3 months and it was directly related to the age of the animals (e.g. degree of calcification). Adult samples were decalcified in 15% EDTA with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 3 weeks and subsequently for 1 week at 40 °C. The specimens were embedded in paraffin and cut in the transverse plane. Serial histological sections were prepared (5 μm thickness for pre‐hatching stages and 10 μm thickness for post‐hatching stages) and stained with haematoxylin‐eosin. Images were taken under bright field using a Leica compound microscope (DMLB2) with a Leica camera (DFC480) attached (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Micro‐computed tomography analysis

MicroCT analysis of the chameleon jaw was performed using the GE Phoenix v|tome|x L 240 laboratory system equipped with a 240 kV/320 W maximum power microfocal X‐ray tube and a high‐contrast flat panel detector DXR250 with a resolution of 2048 × 2048 pixels and a pixel size of 200 × 200 μm. The exposure time was 500 ms; three images were averaged and one image was skipped every 2000 positions. The microCT scan was carried out at an acceleration voltage and X‐ray tube current of 60 kV and 110 μA, respectively. The voxel size of obtained volumes was in the range of 2–18 μm, depending on the size of the jaw. The tomographic reconstruction was produced using GE Phoenix datos| ×2.0 3D computed tomography software. The 3D‐ and 2D‐cross‐section visualizations were performed using volume rendering vg studio max 2.2 software (Volume Graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). The 3D jaw model was clipped according to the polyline path, copying the curvature of the jaw for the purpose of visualizing all teeth in cross‐section. Two‐dimensional transverse cross‐sections of the teeth were performed perpendicular to the polyline.

Laser‐induced breakdown spectroscopy

For the element analysis, soft tissues were mechanically removed from the mandible using scissors. The jaws were macerated in water, boiled and dried. Clean samples were embedded in epoxy resin and ground with diamond paste.

LIBS setup was based on a modified laser ablation system UP 266 MACRO (New Wave, USA) equipped with a pulsed Nd:YAG laser operated at a wavelength of 266 nm. The radiation was transported using a fibre optic system onto the entrance slit of a Czerny‐Turner monochromator (Jobin Yvon, Triax 320, France) with a PI MAX3 ICCD detector (Princeton Instruments). The detection delay time and gate width were set for phosphorus at 0.1 and 8 μs, for calcium at 0.3 and 12 μs, and for magnesium at 0.7 and 3 μs, respectively. The spectral data were collected in three spectral windows centred at 251, 284 and 456 nm for detection of emission lines P I 253.56 nm, Mg II 280.27/Mg I 285.21 nm and Ca I 452.69 nm, respectively.

The ablation experiments were performed at a pulse energy of 10 mJ. The crater size was set to 120 μm, and the distances from crater to crater in both axes were 150 μm.

Microprobe

Microprobe measurements were performed using a Magellan™ 400 SEM. To show the surface topography of the samples, a secondary electron detector and EDX detector for analysing the particles were used. A voltage of 5 kV was selected, and the size of the calculated area was 5 × 5 μm.

Results

Formation of acrodont attachment in pre‐hatching chameleons

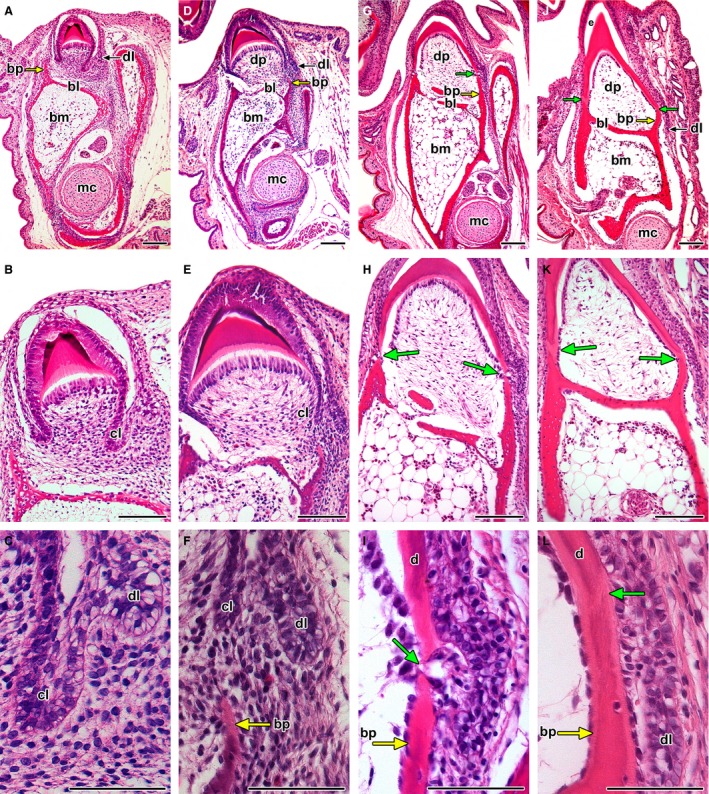

The bases of the rostral and middle teeth in the chameleon formed during the pre‐hatching period (Fig. 2). The cervical loop elongated towards the bone (Fig. 2A–F). Progressively, small, bony pedicles were directed towards the cervical loop and approached the dentin (Fig. 2D,G). Odontoblasts produced predentin that connected dentin to the supporting bone pedicles (Fig. 2I). This fusion process resulted in the formation of a firm morphological unit (Fig. 2J–L).

Figure 2.

Development of the tooth–jaw interface. (A–C) The tooth base forms after mineralization of the crown. Labial bone pedicle (yellow arrow) is formed first while the lingual bone pedicle is behind in development. (D–F) The cervical loop grows deeper into the mesenchyme towards the bone pedicles (yellow arrow). (G–I) Bony pedicles almost in contact with the tooth base formed by dentin. (J–L) The gap between dentin and the underlying bone (green arrow) is filled by a layer of predentin produced by odontoblasts. The tooth base and their surface is formed only by dentin; the enamel did not develop in these areas. bl, bony lamellae; bm, bone marrow; bp, bony pedicle; cl, cervical loop; d, dentin; dl, dental lamina; dp, dental papilla; e, enamel; mc, Meckel cartilage. Haematoxylin‐eosin. Scale bar: (A,B,D,E,G,H,J,K) 100 μm, (C,F,I,L) 50 μm.

At an early stage, the jaw bone had a large amount of bone marrow (Fig. 2). The dental papilla was formed by dense cellular tissue, but later during development, its cellularity decreased to become similar to that found in bone marrow (compare Fig. 2B and K). Bony lamellae formed ahead of lateral bony pedicles and were interposed between the bone marrow and dental pulp cavities (Fig. 2A). The dental papilla remained widely connected to the underlying bony medulla by perforations in the lamella (Fig. 2E,H).

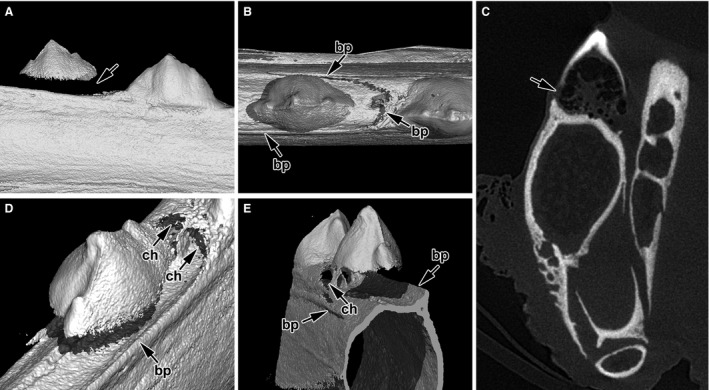

Progressive initiation of teeth in the caudal part of juvenile jaws

Tooth development and attachment to the bone also proceed during the post‐hatching stages (Fig. 3). Growth of the mandible occurred in a caudal direction, such that the most recent teeth were added in the caudal part of the mandible. In the most caudal teeth of juvenile animals, the fusion between tooth bases and bone pedicles was not yet achieved (Fig. 3A,C).

Figure 3.

Tooth initiation in the caudal part of the jaw. (A) Newly added tooth is seen in the caudal part of the juvenile jaw as tooth initiation occurs continually throughout the chameleon life. (B) There is no contact of hard tissues between tooth and bone as yet; bone pedicles are well formed in the labial and rostral area. (C) The mineralized tooth basis does not reach to the jaw bone on the transverse section in microCT; the tooth is held in its position only by soft tissue. (D) A shallow socket in the jaw bone is formed in the future area of tooth–bone fusion where walls are made up of growing bone pedicles. (E) Detail of bony pedicles (arrows) in the rostral area of the tooth. The bone marrow is separated from the future dental pulp. Channels connecting neighbouring teeth develop in advance of tooth–bone fusion. bp, bony pedicle; ch, channel.

Computed tomography revealed that bony pedicles grew from the lamellae in a caudal direction and formed round structures in the shape of a future tooth–bone contact area (Fig. 3B,D,E). Moreover, all juvenile teeth were connected by horizontally oriented channels, which joined each dental pulp to its caudal and rostral neighbours (Fig. 3D,E).

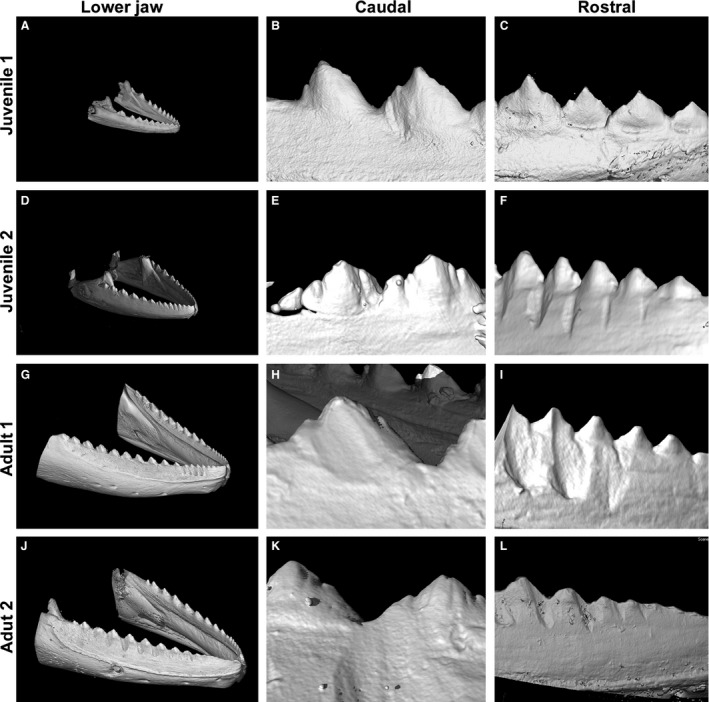

The number of teeth increased with age in the chameleon (Fig. 4). In juveniles, there were 11–13 teeth in the lower jaw quadrant (Fig. 4A,D); in adult animals, their number varied from 15 to 21 (Fig. 4G,J).

Figure 4.

Jaw and tooth morphology using microCT. (A) The number of teeth is the smallest in juvenile chameleons. Teeth are well separated from each other. (B) Caudal teeth are larger and exhibit more complex shapes than rostral teeth. (C) Rostral teeth in juvenile chameleons do not have a uniform size, which is based on altered patterns of eruption. The shallow groove is visible in the area between the tooth and jaw. (D) The jaw becomes more robust and the number of teeth increases. (E) Newly mineralized tooth appears in the most caudal part of the jaw. (F) Teeth bases in the rostral part of the jaw fuse firmly to their neighbours. (G) In adult specimens, the number of teeth increased in the lower jaw. (H) The most caudal teeth exhibit a tricuspid shape. (I) Rostral teeth are firmly fused to each other, forming a saw‐like appearance. (J) The abrasion and fusion of teeth is progressed in the adult specimen. (K) The lateral cusp of caudal teeth tips in the adult specimen are still visible but with apparent signs of abrasion. (L) Individual rostral teeth in adult specimens are hardly recognizable as the fusion and abrasion of tooth cusps has significantly progressed.

Morphological changes in acrodont dentition during post‐hatching stages

There were obvious differences in tooth shape in the rostral and caudal areas of the mandible at all analysed stages (Fig. 4). The smaller and more simply shaped teeth were located in the most rostral part of the mandible; more complex teeth appeared caudally (compare Fig. 4B,E with C,F). Moreover, the abrasion of rostral teeth with increasing age caused progressive loss of tooth morphology and therefore it was more difficult to count their exact number in adult animals (Fig. 4I,L).

Tomography allowed for a more detailed analysis of tooth–jaw and tooth–tooth fusion areas. In juvenile animals, the apical tips of the tooth bases were already connected to the alveolar bone via ankylosis (Fig. 4B,C), and the junctional area between the teeth and jaw bone in the juvenile jaw became almost invisible. An imaginary boundary could be predicted only based on the location of the osteocyte lacunae, as they did not extend to the dental tissue (Supporting Information Fig. S1A,B). In adult specimens, the fusion had progressed so that the exact border between tooth and bone could no longer be localized (Figs 4G–L and S1C–E').

Moreover, firm fusion between neighbouring teeth occurred progressively during post‐hatching development. Therefore, differences between the dental and interdental areas were hardly visible on transverse sections, especially in the rostral area where teeth were smaller and abrasions more advanced (Fig. 4I,L).

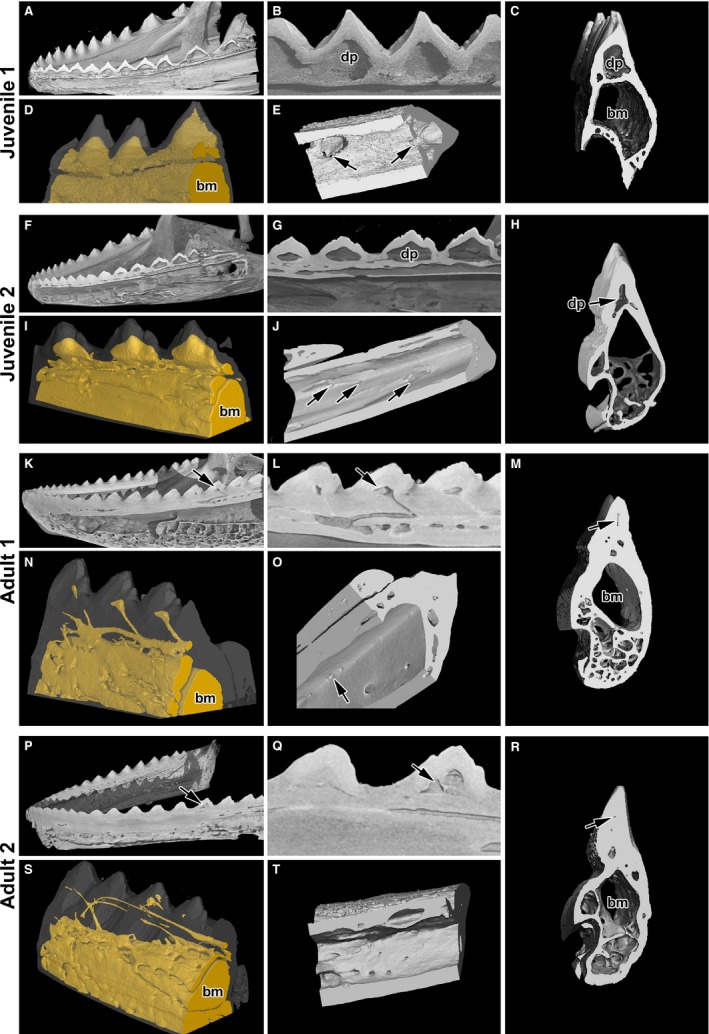

The dental cavity is filled in adult animals

In juvenile animals, a large dental pulp cavity was clearly separated from the underlying bone marrow cavity by bony lamellae (Fig. 5A–E, Supporting Information Fig. S2A–G). Numerous large perforations of the lamella were observed in the central and lateral areas (Fig. 5E,J). The size of the dental papilla decreased with the increasing age of the animals (Figs 5F–J and S2H–M).

Figure 5.

Fusion of teeth to the jaw and neighbouring teeth. (A,B) Sagittal section of the lower jaw in juvenile animals shows fusion of teeth to the bone lamellae as well as tooth to tooth. (C) A distinct dental papilla is separated from the bone marrow by dental lamella on transverse section. (D) Angled view of the cavities, which are labelled in yellow. (E) Ventral view of the perforations connecting bone marrow to dental papilla (arrows). (F,G) The process of deposition of mineralized tissue occurs first in the rostral part of the jaw of juvenile animals. (I) Angled view of smaller dental pulp cavities. (J) Ventral view of reduced perforations connecting bone marrow to dental papilla (arrows). (H,M,R) Transverse sections show reduced dental papilla. (N,S) Remnants of channels and cavities are labelled by yellow filling. (K,L,P,Q) Teeth are firmly connected to the bone. The dental papilla becomes filled by mineralized tissue in adult animals. (O,T) Ventral view of small channels connecting bone marrow to the dental papilla. bm, bone marrow; dp, dental papilla.

Adult chameleons possessed only a rudimentary dental cavity, which was progressively filled with mineralized tissue (Fig. 5K–O). A narrow channel was oriented caudally, interconnecting the dental pulp and bone marrow cavity (Fig. 5N,O, Supporting Information Fig. S3). The dental papilla was partially replaced by dentin, characterized by the presence of parallel tubules oriented towards the central area, as well as by bony matrix distinguishable by the presence of osteocytes (Fig. S1).

In the largest animals, the dental pulp cavity was almost fully filled with mineralized tissue (Fig. 5M) and only very small channels remained (Fig. 5S); only some of the animals had a connection between the dental pulp and bone marrow cavity (Fig. 5Q). In many cases, these channels were no longer even connected to the marrow cavity (Fig. S3G–L). In the rostral teeth, the dental pulp disappeared, and completely filled and unmineralized channels were observed under the bony lamellae (Fig. S3G–I).

The intensity distribution of elements in the tooth–bone area

Because of the morphological changes in the pulp cavity and junction area between the tooth and bone, we hypothesized that extensive changes in elemental composition may occur in the fusion area during the post‐hatching stages to mediate a firm connection between dentin and bone. LIBS analysis was performed with a focus on the key elements contributing to bone and tooth mineralization: calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P) and magnesium (Mg). Intensity maps illustrated the distribution of individual elements (Figs 6 and 7).

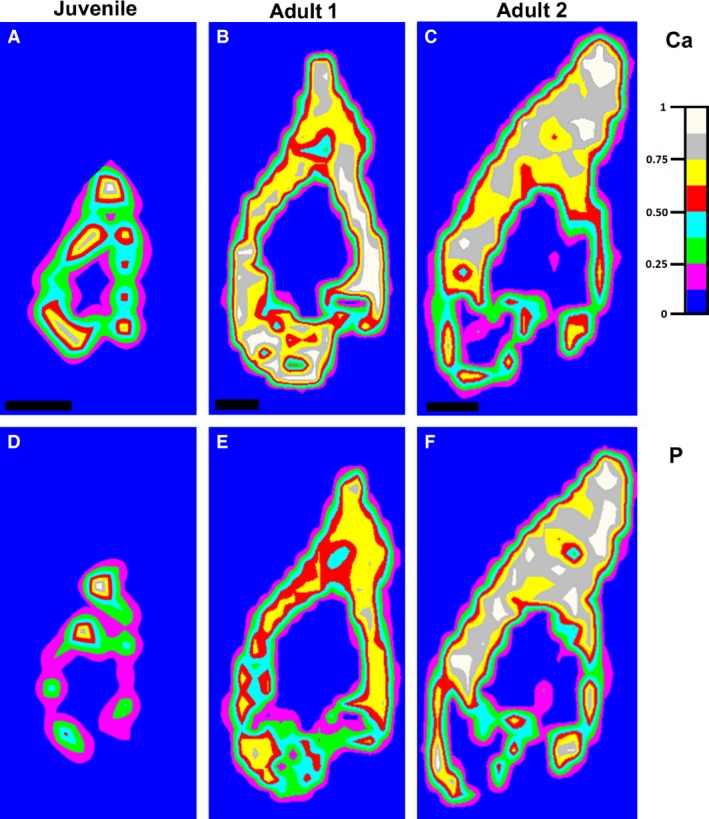

Figure 6.

Distribution maps of calcium and phosphorus in the lower jaw of chameleons by LIBS analysis. (A–C) Distribution maps of calcium measured at 452.69 nm. (D–F) Distribution maps of phosphorus measured at 253.56 nm.

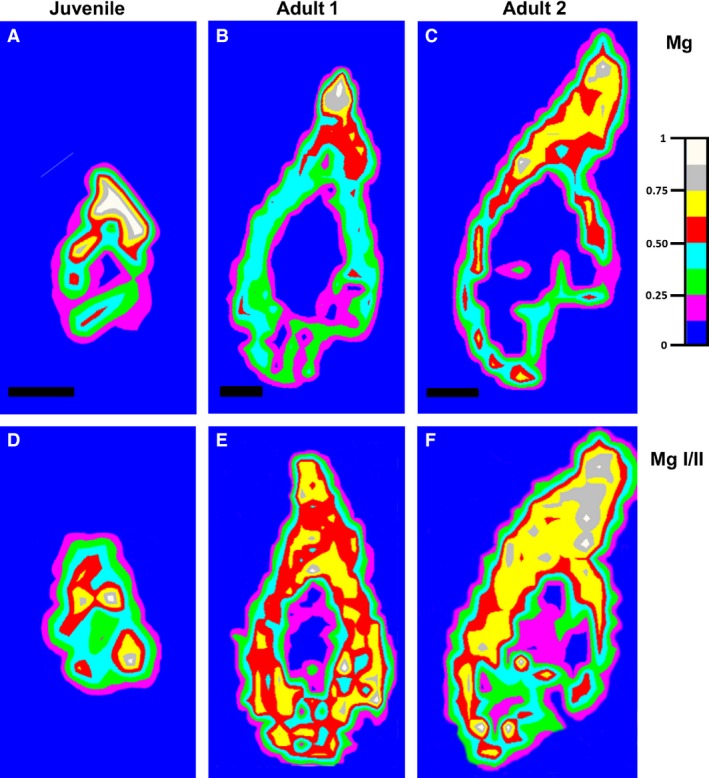

Figure 7.

Distribution maps of magnesium in the lower jaw of chameleons by LIBS analysis. (A–(C) Distribution maps of magnesium measured at 285.21 nm (for Mg I). (D–F) Ratio between distribution maps of magnesium measured at 280.27 nm (Mg II) and 285.21 nm (Mg I).

The intensity of the calcium line was measured at 452.69 nm and that of the phosphorus line at 253.56 nm. For magnesium, the ionic and atomic lines measured at 280.27 and 285.21 nm, respectively, were chosen because of their expected optical thinness (Le Drogoff et al. 2001). Moreover, the ratio MgII/MgI is known to be an indicator of hardness, because these lines are not as affected by self‐absorption (Abdel‐Salam et al. 2007).

The intensity of Ca and P was directly correlated with the age of the specimens (Fig. 6). In juvenile animals, the areas of highest intensity of both of these elements were distributed in the teeth and jaw, which corresponded to ossification centres in the mandible (Fig. 6A,D). The intensity of Ca and P increased when the animals became older, not only in the teeth and jaw bone but also in the junctional area between the two tissues (Fig. 6B,E). In the largest chameleon, the intensity of both elements was attenuated in the area of the lamellar bone, which was thinner than the growing bone of the smaller chameleons (Fig. 6C,F). The highest intensity of Ca and P was concentrated in the area of tooth–bone fusion and also partially in the area of the tooth itself (Fig. 6C,F). The intensity of Mg also increased with the age of the animal (Fig. 7). However, unlike Ca and P, the intensity of Mg in the jaw bone remained relatively low, whereas the intensity expanded in the area of bone–tooth fusion and the tooth area (Fig. 7A–C).

Relative quantity of elements in the tooth and jaw areas

To quantify the LIBS measurements, we used the MicroProbe method (Supporting Information Fig. S4) in the two extreme stages (the smallest juvenile and the largest adult animals), and we measured elements in the apical part of the tooth, in the junctional area between tooth and bone and in the lateral part of the jaw bone.

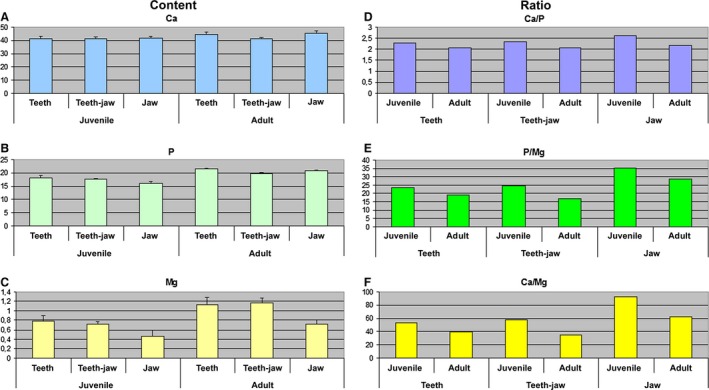

The Ca content did not vary significantly between the tooth and jaw bone areas at any of the analysed stages (Fig. 8A). However, the Ca content was higher at the older stage (Fig. 8A). The amount of P and Mg also increased with age (Fig. 8B,C). When compared with tooth areas, the jaws exhibited significantly lower amounts of Mg at both analysed stages, and the differences between the two stages were statistically significant (Fig. 8C). The P content was significantly lower in the jaw than in the teeth, but only at the juvenile stage (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the comparison of all three areas between stages showed statistically significant differences in P content.

Figure 8.

Microprobe analysis of element content and ratio of elements.

All ratios (Ca/P, P/Mg and Ca/Mg) were higher for each analysed area at juvenile stages in contrast to adult stages (Fig. 8D–F). In juvenile chameleons, although the P/Mg and Ca/Mg ratios in the tooth and tooth–bone fusion area were similar, the ratios of these elements were much higher in the jaw bone (Fig. 8D–F).

Discussion

The jaw apparatus of the chameleon has a unique morphology and functional adaptation for food processing. Chameleon feeding behaviour is exceptional because of its ballistic tongue projection (Gnanamuthu, 1930; Zoond, 1933; Anderson & Deban, 2010; Herrel et al. 2014) as well as its modified skull and hyoideal skeleton with hyoglossal muscles (Mivart, 1870; Rieppel, 1981; Bell, 1989). Its dentition is characterized by the fusion of tooth bases with the jaw bone and their junction along the jaw, which makes dentition very stable and prevents the teeth from falling out. As teeth cannot be replaced, any loss would lead to starvation and eventual death of the animals. Chameleon teeth are designed to hold prey and to apply pressure to kill the insect. Food is swallowed whole or partly chewed. A behavioural study revealed several chewing cycles in which the insect was positioned between jaws and crushed several times before it was transported to the oesophagus (So et al. 1992). MicroCT imaging showed that the shape of the teeth varied along the jaw in accordance with their different functions. Smaller rostral teeth contribute to food transport inside the oral cavity, whereas caudal teeth display a more complex tricuspid morphology, which corresponds to their chewing function.

Tooth–bone fusion

MicroCT revealed a firm fusion of tooth bases with bony pedicles in adult chameleons. This strong fusion between tooth and bone prevents the loss of individual teeth. Chameleon teeth fuse not only to bone but also with neighbouring teeth, both rostrally and caudally. This phenomenon has also been reported in the tuatara (Edmund, 1969; Zaher & Rieppel, 1999). Similarly to chameleons, tuatara teeth are also not replaced, and newly formed teeth are added caudally during development.

Morphological analysis of bony pedicles development revealed their initiation on the labial side and later development on the lingual side. Furthermore, the bony pedicle developed earlier on the rostral side than the caudal side. While the formation of labial and lingual pedicles has been observed previously (Zaher & Rieppel, 1999; Buchtova et al. 2013), the formation of the rostral pedicle could not be observed without detailed microCT analysis. Therefore, a round socket for the future fusion area is formed ahead of tooth mineralization and is probably based on cellular signalling between the cervical loop and bony pedicles. In the mouse, the formation of the tooth–bone interface is precisely controlled by molecules such as OPG or RANK (Ohazama et al. 2004; Alfaqeeh et al. 2013). However, the detailed signalling ‘cross‐talk’ between both structures in the chameleon remains to be investigated in the future.

The structure of pedicles as well as the lamellae between dental pulp and bone marrow cavities appear to have much simpler morphology in comparison with mouse alveolar bones. Alveolar bone in mice arises from several ossification centres (Saffar et al. 1997; Sodek & McKee, 2000), in contrast to chameleon pedicles, which overgrow from the underlying lamellae. Moreover, mouse alveolar bones are initiated separately from the mandibular bone and fuse together much later during postnatal development. Therefore, differences in developmental processes during chameleon pedicle formation can be expected when compared with the mouse.

Dental pulps and bone marrow communication

In juveniles, the cavity of dental pulp is connected with bone marrow by large connections. However, the dental pulp cavity becomes filled over the course of post‐hatching development, and only channels connecting dental pulp to the underlying bone marrow remain visible. Later, only remnants of channels are observed in some areas of the jaw. The probable purpose of communication between pulp and bone‐marrow chambers is to allow blood vessels and nerves to reach the pulp cavity. Channels connecting teeth to their more caudal neighbours are formed very early during development, before the tooth to bone attachment is finished. Similar neurovascular canals connecting adjacent teeth have previously been described in tuatara (Kieser et al. 2009). It is interesting that teeth in juveniles are horizontally connected by channels and therefore serve together as one functional unit. Tooth anlagens are initially built as separate elements and then connected to underlying bone, which requires very complex patterning steps to build all of the communications and channels in the correct areas before mineralization occurs.

In the adult chameleon, the filling of the dental pulp cavity leads to the loss of connection to the underlying bone and disappearance of vascular supply in this area. In the largest animals, the connection channels between the bone marrow and the tooth are reduced. Therefore, it seems improbable that tooth tissue remains fully vascularized and innervated, as observed in mammals. Furthermore, odontoblasts in mammals are maintained throughout life, and though they are active for a very long time in a healthy environment, they can also be reactivated to produce reactionary dentin (Smith & Lesot, 2001). However, in the chameleon, not even remnants of a cavity were observed in the most rostral teeth. Here, we focused only on hard bone structures; however, in the future, it will be necessary to investigate dentin ultrastructure in chameleons and possibly the presence of odontoblast processes in this area, including the cellular events involved in dental pulp and channel filling, such as cellular degradation, the fate of odontoblasts and the arrangement or disappearance of vessels and nerves in the pulp cavity.

Mineral content changes during development

To study the progress of mineralization in teeth as well as underlying bone, we analysed the distribution of calcium, phosphorus and magnesium in hard tissues and their changes with age. LIBS was carried out to map the intensity of individual elements in the area of teeth, bone and tooth attachment at three different post‐hatching stages. There is a general lack of information about the distribution of elements from comparative points of view and the chemical composition of reptilian teeth. The wavelength‐dispersive electron microprobe has been used to evaluate the teeth of recent and fossilized animals (Dauphin & Williams, 2007, 2008). Those authors found an approximately two‐fold higher content of calcium in enamel in comparison with dentin, whereas Mg was enriched in dentin (Dauphin & Williams, 2007). In crocodiles, X‐ray powder diffraction (XRD) was used to measure mineral content in dentin, enamel and cementum (Enax et al. 2013). The advantage of this method was the evaluation of the exact amount of elements from individual material. Therefore, we combined both analytical approaches to determine mineral content differences, and we also performed quantitative measurements using an EDX detector on juvenile and adult animals, which allowed the determination of element content in selected areas.

Calcium, phosphorus and magnesium have been selected as the most common elements to analyse the degree of mineralization in different areas of dental or bone tissues in developing or experimental mammalian models or even pathological processes (Steinfort et al. 1991; Aoba et al. 1992a,b; Tjaderhane et al. 1995; Akiba et al. 2006). In the teeth and jaw bone areas of chameleons, the intensity of calcium and phosphorus was low in juvenile animals but significantly increased in adult animals. The borders between tooth and bone areas become invisible with advancing animal age, and the mineral composition confirmed the very firm connections for protection against loss of teeth. Similarly, in humans the calcium and phosphorus content increases during the mineralization of dentin and enamel (Arnold & Gaengler, 2007).

Interestingly, the calcium and phosphorus content was lower in the jaw bone than in the teeth, especially at the juvenile stage. This could explain the broken jaw bones during fights between animals, as the bone is much weaker than the junctional tooth–bone areas.

Magnesium is known to be associated with the mineralization of teeth and bone tissue. It has been proposed that magnesium can replace calcium to bind to phosphate. Magnesium can be involved in the process of biological apatite crystal formation (Bigi et al. 1992) and mineral metabolism through activation of alkaline phosphatase (Althoff et al. 1982). Areas of high magnesium content were found in the newly formed dentin of rat incisors where the calcium/phosphorus ratio was low (Wiesmann et al. 1997). In chameleons, the magnesium content increased with animal age. The jaw bones had a significantly lower magnesium content in comparison with teeth, and differences between the two stages were also statistically significant.

Our recent observations suggest a strictly regulated progression of the mineralization process, both in time and in space. However, future comparative studies between acrodont and pleurodont dentition will be necessary.

Conclusion

Here, age‐related changes in morphology and mineral content were documented in the tooth–bone interface area, which contribute to firm and fully mineralized fusion between two types of tissues as a result of physiological ankylosis in chameleons. However, these results raise two complementary questions: (i) which cell types are involved in the progressive filling of the dental pulpal cavity and (ii) what are the regulatory mechanisms specifying the functional differentiation in the junction area? This mineralization of the cavity impairs all possibilities of a later reparative process. Further study will be necessary to analyse the cellular processes involved in filling the dental pulp cavity and increasing mineralization in the underlying tooth–bone junction area. Moreover, a comparison between mammalian and reptilian models may provide new and useful information to study the molecular interactions at the tooth–bone interface during development.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Transverse sections of the dental pulp cavity in juvenile (A,B) and adult (C–E, E’) animals.

Fig. S2. Channel formation during the fusion of teeth to the jaw in juvenile animals.

Fig. S3. Channel formation during the fusion of teeth to the jaw in adult animals.

Fig. S4. Typical emission spectra of the tooth, jaw and transitional area in both analysed stages.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (14‐37368G to M.B. lab and O.Z., 14‐29273P to J.Š.), Grant Agency of the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences Brno (61/2013/FVL to H.D.) and International Cooperation by Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic (M200451201). T.Z., J.K. and K.N. acknowledge the CEITEC 2020 (LQ1601) with financial support from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under the National Sustainability Programme II. We thank also Jan Hříbal for material support. This contribution is free of conflict of interest.

References

- Abdel‐Salam ZA, Galmed AH, Tognoni E, et al. (2007) Estimation of calcified tissues hardness via calcium and magnesium ionic to atomic line intensity ratio in laser induced breakdown spectra. Spectrochim Acta, Part B 62, 1343–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba N, Sasano Y, Suzuki O, et al. (2006) Characterization of dentin formed in transplanted rat molars by electron probe microanalysis. Calcif Tissue Int 78, 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfaqeeh SA, Gaete M, Tucker AS (2013) Interactions of the tooth and bone during development. J Dent Res 92, 1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althoff J, Quint P, Krefting ER, et al. (1982) Morphological studies on the epiphyseal growth plate combined with biochemical and X‐ray microprobe analyses. Histochemistry 74, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CV, Deban SM (2010) Ballistic tongue projection in chameleons maintains high performance at low temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 5495–5499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L, Malmgren B (1999) The problem of dentoalveolar ankylosis and subsequent replacement resorption in the growing patient. Aust Endod J 25, 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoba T, Moreno EC, Shimoda S (1992a) Competitive adsorption of magnesium and calcium ions onto synthetic and biological apatites. Calcif Tissue Int 51, 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoba T, Shimoda S, Moreno EC (1992b) Labile or surface pools of magnesium, sodium, and potassium in developing porcine enamel mineral. J Dent Res 71, 1826–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WH, Gaengler P (2007) Quantitative analysis of the calcium and phosphorus content of developing and permanent human teeth. Ann Anat 189, 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DA (1989) Functional anatomy of chameleon tongue. Zool Jb Anat 119, 313–336. [Google Scholar]

- Bigi A, Foresti E, Gregorini R, et al. (1992) The role of magnesium on the structure of biological apatites. Calcif Tissue Int 50, 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchtova M, Zahradnicek O, Balkova S, et al. (2013) Odontogenesis in the Veiled Chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus). Arch Oral Biol 58, 118–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrage BR (1973) Comparative ecology and behaviour of Chamaeleo pumilis pumilis (Gemelin) and C. namaguensis A. Smith (Sauria: Chamaeleonidae). Ann S Aft Mus 61, 1–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin Y, Williams CT (2007) The chemical compositions of dentine and enamel from recent reptile and mammal teeth – variability in the diagenetic changes of fossil teeth. Cryst Eng Comm 9, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin Y, Williams CT (2008) Chemical composition of enamel and dentine in modern reptile teeth. Mineral Mag 72, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Edmund AG (1969) Dentition In: Biology of the Reptile (ed. Gans C.), pp. 117–200. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Enax J, Fabritius HO, Rack A, et al. (2013) Characterization of crocodile teeth: correlation of composition, microstructure, and hardness. J Struct Biol 184, 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaengler P (1991) Evolution of tooth attachment in lower vertebrates to tetrapods In: Mechanisms and Phylogeny of Mineralization in Biological Systems (eds Suga S, Nakahara H.), pp. 173–185. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gaengler P, Metzler E (1992) The periodontal differentiation in the phylogeny of teeth – an overview. J Periodontal Res 27, 214–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiova M, Kaiser J, Novotny K, et al. (2010) Investigation of the osteitis deformans phases in snake vertebrae by double‐pulse laser‐induced breakdown spectroscopy. Anal Bioanal Chem 398, 1095–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanamuthu CP (1930) The anatomy and mechanism of the tongue of Chamaeleon calcaratus . Proc Zool Soc Lond 1930, 467–486. [Google Scholar]

- Herrel A, Redding CL, Meyers JJ, et al. (2014) The scaling of tongue projection in the veiled chameleon, Chamaeleo calyptratus . Zoology (Jena) 117, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser JA, Tkatchenko T, Dean MC, et al. (2009) Microstructure of dental hard tissues and bone in the Tuatara dentary, Sphenodon punctatus (Diapsida: Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia). Front Oral Biol 13, 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Drogoff B, Margot J, Chaker M, et al. (2001) Temporal characterization of femtosecond laser pulses induced plasma for spectrochemical analysis of aluminum alloys. Spectrochim Acta Part B, 56, 987–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas PW(1979) Basic principles of tooth design In: Teeth, Form, Function, Evolution. (ed. Kurten B.), pp. 154 New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JE, Anderton X, Flores‐De‐Jacoby L, et al. (2002) Caiman periodontium as an intermediate between basal vertebrate ankylosis‐type attachment and mammalian ‘true’ periodontium. Microsc Res Tech 59, 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mivart SG (1870) On the myology of Chamaelon parsonii . Proc Zool Soc Lond 1870, 850–890. [Google Scholar]

- Ohazama A, Courtney JM, Sharpe PT (2004) Opg, Rank, and Rankl in tooth development: co‐ordination of odontogenesis and osteogenesis. J Dent Res 83, 241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JW (1984) From reptile to mammals: evolutionary considerations of dentition with emphasis on tooth attachment. Symp Zool Soc Lond 52, 549–574. [Google Scholar]

- Rieppel O (1981) The skull and jaw adductor musculature in chameleons. Rev Suisse Zool 88, 433–445. [Google Scholar]

- Saffar JL, Lasfargues JJ, Cherruau M (1997) Alveolar bone and the alveolar process: the socket that is never stable. Periodontol 2000 13, 76–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ, Lesot H (2001) Induction and regulation of crown dentinogenesis: embryonic events as a template for dental tissue repair? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 12, 425–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So K‐KJ, Wainwright PC, Bennett AF (1992) Kinematics of prey processing in Chamaeleo jacksonii: conservation of function with morphological specialization. J Zool 226, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sodek J, McKee MD (2000) Molecular and cellular biology of alveolar bone. Periodontol 2000 98(24), 99–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfort J, Driessens FC, Heijligers HJ, et al. (1991) The distribution of magnesium in developing rat incisor dentin. J Dent Res 70, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart‐Fox DM, Whiting MJ (2005) Male dwarf chameleons assess risk of courting large, aggressive females. Biol Lett 1, 231–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Cate AR (1994) Development of The Tooth and its Supporting Tissue. In: Oral histology: development, structure and function St. Louis: Mosby‐Year Book. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaderhane L, Hietala EL, Larmas M (1995) Mineral element analysis of carious and sound rat dentin by electron probe microanalyzer combined with back‐scattered electron image. J Dent Res 74, 1770–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesmann HP, Tkotz T, Joos U, et al. (1997) Magnesium in newly formed dentin mineral of rat incisor. J Bone Miner Res 12, 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RA (1974) Implications of atomic substitutions and other structural details in apatites. J Dent Res 53, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaher H, Rieppel O (1999) Tooth implantation and replacement in squamates, with special reference to mosasaurs lizards and snakes. Am Mus Novit 3271, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zoond A (1933) The mechanism of projection of the chameleon's tongue. J Exp Biol 10, 174–185. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Transverse sections of the dental pulp cavity in juvenile (A,B) and adult (C–E, E’) animals.

Fig. S2. Channel formation during the fusion of teeth to the jaw in juvenile animals.

Fig. S3. Channel formation during the fusion of teeth to the jaw in adult animals.

Fig. S4. Typical emission spectra of the tooth, jaw and transitional area in both analysed stages.