Abstract

Peritoneal dissemination represents a devastating form of gastric cancer (GC) progression with a dismal prognosis. There is no effective therapy for this condition. The 5-year survival rate of patients with peritoneal dissemination is 2%, even including patients with only microscopic free cancer cells without macroscopic peritoneal nodules. The mechanism of peritoneal dissemination of GC involves several steps: detachment of cancer cells from the primary tumor, survival in the free abdominal cavity, attachment to the distant peritoneum, invasion into the subperitoneal space and proliferation with angiogenesis. These steps are not mutually exclusive, and combinations of different molecular mechanisms can occur in each process of peritoneal dissemination. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular events involved in peritoneal dissemination is important and should be systematically pursued. It is crucial to identify novel strategies for the prevention of this condition and for identification of markers of prognosis and the development of molecular-targeted therapies. In this review, we provide an overview of recently published articles addressing the molecular mechanisms of peritoneal dissemination of GC to provide an update on what is currently known in this field and to propose novel promising candidates for use in diagnosis and as therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Peritoneal dissemination, Microenvironment, Biomarker, Molecular target

Core tip: Peritoneal metastasis is the most common form of recurrence in gastric cancer, and it is associated with a poor prognosis. The development of peritoneal metastasis is a multistep process, beginning with the detachment of cancer cells from the primary tumor, followed by their attachment to peritoneal mesothelial cells, retraction of the mesothelial cells, exposure of the basement membrane, proliferation and finally growth with induction of angiogenesis. The aim of this review is to provide an update of our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms that promote peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. This information may aid in the design of new and effective treatments and diagnostics for this condition.

INTRODUCTION

In metastatic gastric cancer (GC), direct seeding into the peritoneal cavity occurs in more than 55%-60% of patients[1-3]. The resulting peritoneal dissemination is the most common and important clinical manifestation, leading to a poor prognosis[4]. A complete cure through surgery is difficult, and chemotherapy has been the first choice for treatment[5-7]. However, chemotherapy for peritoneal dissemination is inadequate due to insufficient drug delivery, and due to symptoms such as intestinal obstruction and abdominal bloating, patients have a poor prognosis[2,8,9].

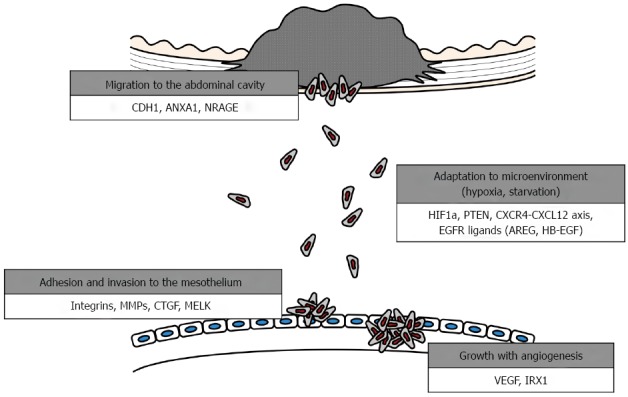

The development of this clinical entity can be explained using several biological models. A better understanding of the underlying tumor kinetics and cellular dissemination mechanisms will guide clinical decisions to improve therapeutic outcomes and aid in the development of targeted therapies[10-12]. The development of peritoneal metastasis is a multistep process, as follows: (1) detachment of cancer cells from the primary tumor; (2) survival in the microenvironment of the abdominal cavity; (3) attachment of free tumor cells to peritoneal mesothelial cells and invasion of the basement membrane; and (4) tumor growth with the onset of angiogenesis[13-16] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps for formation of peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. CDH1: Cadherin 1, E-cadherin; ANXA1: Annexin 1; NRAGE: Neurotrophin receptor-interacting melanoma antigen-encoding gene homolog; HIF1A: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α subunit; PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homolog; CXCR4: C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; CXCL12: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; AREG: Amphiregulin; HBEGF: Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; MMP7: Matrix metalloproteinase 7; CTGF: Connective tissue growth factor; MELK: Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase; VEGFA: Vascular endothelial growth factor A; IRX1: Iroquois homeobox 1.

A comprehensive understanding of the molecular events involved in each step of peritoneal dissemination is important and should be systematically pursued. It is urgent to identify markers of prognosis and novel strategies for the prevention of this condition and to develop molecular-targeted therapies[17-19]. In this article, we review the current knowledge regarding the molecules responsible for each step of peritoneal dissemination formation and molecular markers in tumor tissues and abdominal fluids. Although these molecules may act at multiple steps, we describe their role in each process according to their putative primary contribution to peritoneal dissemination.

MOLECULES FACILITATING PENETRATION OF CANCER CELLS THROUGH THE GASTRIC WALL

Tumor dissemination is initiated from the primary tumor and is a multistep process. First, individual or clusters of tumor cells must invade the gastric wall, detach from the primary tumor mass and gain access to the peritoneal cavity[13,20]. Detachment can occur by several mechanisms, and the most frequent one in gastrointestinal cancers is spontaneous exfoliation of tumor cells from cancers that have invaded the serosa. Accordingly, migration and invasion of GC cells are required for this step (detachment and penetration)[10]. The genes reported to be involved in this step of peritoneal dissemination in GC and additional key features and functions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of molecules responsible for formation of peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer

| Symbol | Full name | Location | Biological functions | Oncological functions | Interacting molecules, pathways | Ref. |

| Penetration of the gastric wall | ||||||

| CDH1 | Cadherin 1, E-cadherin | 16q22.1 | Cell-cell adhesion | Proliferation, invasion, migration | Wnt, Rho GTPases, NF-κB pathways, EMT | [22] |

| ANXA1 | Annexin 1 | 9q21.13 | Calcium and membrane-binding protein | Proliferation, apoptosis, tumorigenesis | MAPK/ERK pathway | [30] |

| NRAGE | Neurotrophin receptor-interacting melanoma antigen-encoding gene homolog | Xp11.23 | Normal developmental apoptosis of sympathetic, sensory and motor neurons | Proliferation, apoptosis | AATF, p75NTR, PCNA | [37] |

| Survival and proliferation in the abdominal cavity | ||||||

| HIF1A | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α subunit | 14q23.2 | Regulator of cellular and systemic homeostatic response to hypoxia | Energy metabolism, angiogenesis, apoptosis | Reactive oxygen species, NF-κB pathway | [20] |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | 10 q23 | Dephosphorylating phosphoinositide substrates | Growth, migration | PI3K/NF-κB pathway, FAK | [48] |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 | 2q21 | Chemokine receptor | Invasion, metastasis | PI3K/AKT/NF-κB, mTOR pathways | [52,55] |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 | 10q11.1 | Ligand for the G-protein-coupled receptor and CXCR4 | Metastasis, angiogenesis | ||

| AREG | Amphiregulin | 4q13.3 | Epidermal growth factor, mammary gland, oocyte and bone tissue development | Proliferation, migration | EGF, TGF-α, CXCL12/CXCR4 axis | [60] |

| HBEGF | Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor | 5q23 | Ligand for EGFR | |||

| Adhesion and invasion to the mesothelium | ||||||

| ITGA3 | Integrin subunit a 3 | 17q21.33 | Cell surface adhesion | Metastasis, adhesion | Laminin | [69] |

| MMP7 | Matrix metalloproteinase 7 | 11q22.2 | Extracellular matrix degradation | Proliferation, invasion | E-cadherin, TGF-β, EMT | [75] |

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor | 6q23.1 | Chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation, cell adhesion | Growth, migration, adhesion | Integrin a3b1, PDGF | [79] |

| MELK | Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase | 9p13.2 | Cell cycle-dependent protein kinase | Apoptosis, chemoresistance | RhoA, FAK, Bcl-GL | [84] |

| Growth and angiogenesis | ||||||

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | 6p21.1 | Proliferation and migration of vascular endothelial cells | Angiogenesis | FAK, PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK pathways | [87] |

| IRX1 | Iroquois homeobox 1 | 5p15.33 | Pattern formation in the embryo | Metastasis, angiogenesis | VEGFA | [90] |

E-cadherin (CDH1)

E-cadherin is a calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion molecule that plays a crucial role in establishing the epithelial architecture and maintaining cell polarity and differentiation[21,22]. GC cells can disseminate to distant organs, and there are dramatic alterations between cancer cells and extracellular-matrix components, indicating that alterations in cell-cell adhesion and cell-matrix adhesion can lead to tumor progression. In addition to its role in cell-cell adhesion, E-cadherin and the cadherin-catenin complex modulate various signaling pathways in epithelial cells, including Wnt signaling, Rho GTPases, NF-κB pathways and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition that accelerates cell motility and invasiveness[23-25]. Therefore, dysregulation of E-cadherin contributes to tumor invasion and progression. Promoter hypermethylation induced by Helicobacter pylori infection and mutation of CDH1 led to the inhibition of expression or activity of E-cadherin[21,26]. Dysfunction of E-cadherin is broadly involved in GC progression and predominantly contributes during invasion of the gastric wall and migration of cancer cells into the free abdominal space.

Annexin 1

Annexin 1 (ANXA1) is a member of the calcium- and membrane-binding proteins and was initially characterized as a glucocorticoid-regulated anti-inflammatory protein[27]. Recent evidence suggests that ANXA1 has a wide range of cellular functions, such as membrane aggregation, phagocytosis, proliferation, apoptosis and tumorigenesis[28]. Overexpression of ANXA1 causes constitutive activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway in various cells[28,29].

Cheng et al[30] found that high ANXA1 expression was significantly associated with increased serosal invasion and peritoneal metastasis, and poorer overall survival in GC patients. Furthermore, in vitro studies illustrated a novel regulatory mechanism involving formyl peptide receptors, ERK1/2 and ITGB1BP1, by which ANXA1 regulates GC cell invasiveness. An in vivo study revealed that shRNA-mediated inhibition of ANXA1 significantly suppressed formation of intraperitoneal nodules[30]. These results suggested that ANXA1 facilitates GC cell invasion in the gastric wall and spread to the abdominal cavity.

Neurotrophin receptor-interacting melanoma antigen-encoding gene homolog

The melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) genes encode multifunctional proteins that regulate the cell cycle, differentiation and survival[31,32]. A unique member of the type II MAGE family, neurotrophin receptor-interacting melanoma antigen-encoding gene homolog (NRAGE), also known as MAGE-D1, is located on the X chromosome and encodes an 86 kDa protein[33]. NRAGE is highly expressed in the nervous system and was originally reported to act as a pro-apoptotic factor required for the normal developmental apoptosis of sympathetic, sensory and motor neurons[34,35]. To date, there are conflicting reports regarding the expression and oncogenic significance of NRAGE in multiple cancers, including lung, breast and esophageal cancer, as well as melanoma[35,36].

We recently evaluated the expression and function of NRAGE in GC and found that NRAGE mRNA expression was positively correlated with that of the apoptosis-antagonizing transcription factor[37]. SiRNA-mediated knockdown of NRAGE significantly decreased proliferation, migration and invasion of GC cells. A stepwise elevation in NRAGE mRNA expression in GC tissues was observed with increasing disease stage, and high NRAGE expression was associated with serosal invasion of the tumor and positive lavage cytology and, subsequently, shorter survival[37]. Our results indicated that NRAGE may contribute to peritoneal dissemination of GC in terms of invasion of the gastric wall and detachment from the primary tumor to gain access to the peritoneal cavity.

CONTRIBUTORS TO SURVIVAL AND PROLIFERATION IN THE MICROENVIRONMENT OF THE INTRA-ABDOMINAL CAVITY

Once free GC cells are seeded in the peritoneal cavity, they spread and finally adhere to the distant mesothelium. Between seeding and adhesion to the mesothelium, cancer cells must overcome several obstacles[10,38,39]. The microenvironment of the free abdominal space is hypoxic and deficient in glucose, but cancer cells must survive, proliferate and migrate in this environment[40,41]. Functionally and genetically heterogeneous tumors may have common and intrinsic mechanisms of tumor maintenance based on the context of a given microenvironment. Below, we discuss genes that contribute to the ability of GC cells to survive in a given microenvironment (Table 1).

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

Hypoxia is a hallmark of solid tumor formation and is associated with local invasion, metastatic spread, resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and poor prognosis in a number of human carcinomas[42]. The free intraperitoneal space is associated with a specific microenvironment and results in starved hypoxic GC cells that must survive under these environmental conditions until they can attach to the mesothelium[43]. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is a key transcription factor involved in the cellular response to hypoxic conditions and is also involved in angiogenesis and glycolysis[42,43].

Miao et al[20] showed a positive correlation between HIF-1α expression and GC peritoneal dissemination. Furthermore, GC stem/progenitor cells, which were identified using Hoechst 33342 staining, increased in primary GC cells under hypoxic conditions in vitro and showed an enhanced capacity for self-renewal but reduced differentiation mediated by HIF-1α. In mouse models, GC stem/progenitor cells preferentially resided in the hypoxic peritoneal zone of omentum-associated lymphoid tissues, also known as milky spots[20]. These findings supported the involvement of HIF-1α in the development of peritoneal dissemination, particularly in the adaptation to the hypoxic microenvironment in the abdominal cavity.

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) is located on human chromosome 10q23, a locus that is highly susceptible to loss of heterozygosity, and it is one of the most frequently mutated tumor suppressors in multiple cancers[44]. PTEN negatively regulates the PI3K signaling pathway due to its lipid phosphatase activity, thereby inhibiting the activation of downstream components, such as AKT and NF-κB, stimulating cancer cell proliferation and growth[45,46]. PTEN could interact with and dephosphorylate focal adhesion kinase (FAK), leading to the inhibition of integrin-mediated cell spreading and cell migration[46,47]. Zhang et al[48] demonstrated that PTEN overexpression or knockdown in GC cells led to the down-regulation or up-regulation of FAK, respectively, and decreased or increased cell invasion, respectively. Using orthotropic GC nude mouse models, the researchers found that the metastatic peritoneum nodules were fewer and smaller in mice injected with GC cells overexpressing PTEN[48]. Accordingly, the PTEN/PI3K/NF-κB/FAK axis is believed to be one of the key pathways involved in the peritoneal dissemination of GC.

CXCL12/CXCR4 axis

Chemokines are a superfamily of small, structurally related chemoattractant cytokines[49]. Chemokines bind to G protein-coupled receptors on leukocytes and stem cells and function through guanine nucleotide-binding proteins to initiate intracellular signaling cascades that promote migration toward the chemokine source[50]. Among all chemokine receptors, CXCR4 is of particular importance in solid cancer metastasis and migration[51,52]. CXCL12 is the only known ligand for CXCR4. It activates the CXCR4 receptor and attracts circulating CXCR4-expressing cells to peripheral tissues[51,53].

The CXCL12/CXCR4 axis regulates a wide variety of downstream signaling pathways related to chemotaxis, cell survival, and/or proliferation[54]. Yasumoto et al[55] evaluated the role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in peritoneal dissemination of GC. The researchers first found that CXCR4 was abundant in the malignant ascites of mouse models using cells established from human malignant ascites of GC. CXCL12 was strongly expressed on peritoneal mesothelial cells, and higher levels of CXCL12 were detected in the malignant ascites fluid from patients with peritoneal dissemination of GC, compared to those in normal fluids in the peritoneal cavity.

CXCR4 expression in the primary tumors of patients with advanced GC was significantly associated with the occurrence of peritoneal dissemination. Chen et al[53] reported that the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis mediated cell migration via the mTOR pathway, and mTOR pathway inhibitors decreased CXCL12-stimulated cell migration in GC. Izumi et al[52] evaluated the tumor-promoting effects of CXCL12 derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts. CXCL12/CXCR4 activation by cancer-associated fibroblasts mediated integrin b1 clustering at the cell surface and promoted invasion of GC cells. Inhibition of CXCL12 decreased the invasive ability of GC cells via the suppression of integrin b1/FAK signaling. These results suggested that blocking the CXCL12/CXCR4 interaction or inhibiting downstream intracellular signaling pathways may be a useful strategy for cancer therapy[52].

To date, several preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted on anti-CXCL12 agents[56]. AMD3100 [recently renamed Mozobil (plerixafor injection)] was reported to inhibit CXCL12-induced tumor cell migration and downstream signaling and also to suppress CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling in murine tumor models. This drug is already approved for clinical use in patients with leukemia[57]. The therapeutic efficacy of several CXCR4 antagonists is also currently being tested in clinical trials[52].

Epidermal growth factor receptor ligands

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a member of a family of closely related growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases that includes HER2. Many family members have been identified as therapeutic targets for the treatment of various cancers[58]. In fact, treatment with trastuzumab, a human monoclonal antibody specific for HER2, has shown survival benefits in patients with advanced, HER2-positive GC[59]. To date, seven ligands for EGFR have been identified: epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor-α; heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF); amphiregulin (AREG); betacellulin; epiregulin; and epigen. Among them, AREG and HB-EGF have been reported to play a crucial role in tumor progression[60,61].

AREG and HB-EGF are synthesized as type I transmembrane protein precursors and are expressed on the cell surface as pro-amphiregulin and pro-HB-EGF, respectively[58,61,62]. Yasumoto et al[60] reported that AREG and HB-EGF were abundant in the ascites fluids from GC patients. AREG promoted the proliferation of CXCR4-expressing GC cells, and HB-EGF markedly induced migration of fibroblasts. HB-EGF and CXCL12 together enhanced TNF-α-converting enzyme-dependent AREG shedding from functional CXCR4-expressing GC cells[60]. These findings suggested that targeting tumor cells and their microenvironments via AREG and HB-EGF inhibition represents a promising treatment approach for peritoneal dissemination in GC.

ADHESION TO THE DISTANT MESOTHELIUM AND PENETRATION INTO THE SUBMESOTHELIAL SPACE

Peritoneal-free cancer cells directly attach to the peritoneal surface; however, the mesothelium, the innermost monolayer of the peritoneum, has a primitive protective mechanism against adhesion of exogenous cells. Several chemokine receptors and cell adherens have been reported to facilitate the attachment of GC cells to the mesothelium[10]. Moreover, most free cancer cells die off due to the peritoneal-blood barrier even after the attachment of peritoneal free cancer cells to the peritoneum[63,64]. Several populations of free GC cells enable successive localization of intraperitoneal dissemination by penetrating into the submesothelial space due to the production of growth factors and matrix metalloproteinases, which induce the contraction of mesothelial cells, exposing the submesothelial basement membrane[65]. Below, we introduce several key molecules promoting this aspect of adhesion and penetration (Table 1).

Integrins

Adhesion of GC cells to the peritoneum is a key step during development of peritoneal dissemination[66]. The integrin family of cell adhesion molecules serves as adhesion receptors for ECM proteins and cellular counterligands[66,67]. Nishimori et al[68] selected a GC cell line showing high peritoneal metastatic potential and found that these cells preferentially overexpressed a1-a6 integrins, in contrast to the parental cell line, which had a low peritoneal diffusion capability. Treatment with functional blocking antibodies to tumor integrins was found to decrease peritoneal dissemination.

Takatsuki et al[69] reported that integrin a3b1 played a critical role in cancer cell adhesion to the peritoneum. Monoclonal antibodies specific to integrin a3b1 inhibited GC cell adhesion to excised peritoneum and cell growth. In peritoneal mesothelial cells, mRNAs for laminin-5 and laminin-10/11, which have been identified as high-affinity ligands for integrin a3b1, were detected. Furthermore, pretreatment of excised peritoneum with an antibody to laminin-5 significantly inhibited the adhesion of GC cells[69]. Taken together, these findings have demonstrated that integrin strongly mediates the initial attachment of GC cells during peritoneal dissemination.

Matrix metalloproteinase 7

MMPs are a family of endogenous calcium- and zinc-dependent proteolytic enzymes that are capable of degrading most ECM components, as well as regulating other enzymes, chemokines and even cell receptors[70,71]. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7) is a distinct family member with proteolytic activity against a wide range of biomolecules and is recognized as pivotal in the MMP family because it is the most potent member at activating other MMPs (i.e., MMP2 and MMP9) to degrade the ECM[72,73]. By degrading ECM proteins and regulating the activity of other biomolecules in the body, MMP7 may play a central role in stromal invasion of GC cells during formation of peritoneal dissemination[71,74]. Yonemura et al[75] reported that specific antisense oligonucleotides that inhibit MMP7 suppressed the invasive ability of GC cells without modifying cell proliferation in a mouse xenograft peritoneal dissemination model, leading to prolonged survival compared with control mice.

Connective tissue growth factor

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is a secretory protein and has been reported to be a multifunctional growth factor involved in wound healing, inflammation, cell adhesion, chemotaxis, apoptosis, tumor growth and fibrosis[76,77]. Additionally, CTGF promotes angiogenesis by regulating endothelial cell growth, migration, adhesion and survival[77,78]. Chen et al[79] evaluated the expression and oncological roles of CTGF in GC. CTGF overexpression or treatment with recombinant CTGF protein significantly inhibited GC cell adhesion. In vivo peritoneal dissemination models demonstrated that stable CTGF transfectants markedly decreased the number and size of the peritoneal nodules in the mesentery. Blocking integrin a3b1 inhibited GC cell adhesion to recombinant CTGF. Patients expressing low CTGF levels had a significantly higher prevalence of peritoneal dissemination and a lower probability of survival after surgery compared with those expressing high CTGF levels[79]. The authors concluded that CTGF was an anti-adhesion protein in peritoneal dissemination of GC and that recombinant CTGF may be a therapeutic option for patients with advanced GC.

Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase

Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) is a cell cycle-dependent protein kinase that plays a key functional role in multiple cellular processes, such as proliferation, cell cycle progression, mitosis and spliceosome assembly[80]. MELK interacts with and phosphorylates CDC25B on Ser323 to regulate G2/M progression[81]. MELK has been reported to be frequently elevated in multiple cancers and is correlated with a poor prognosis[82,83]. In addition, MELK interacts with Bcl-GL through its amino-terminal region and suppresses apoptosis[81,83].

Du et al[84] found that MELK mRNA and protein expression were both elevated in GC tissues, and this was associated with chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil. Knockdown of MELK significantly suppressed cell proliferation, migration and invasion of GC in vitro and in mouse xenograft peritoneal dissemination models in vivo; it decreased the percentage of cells in the G1/G0 phase and increased those in the G2/M and S phases. Moreover, knockdown of MELK decreased the amount of actin stress fibers, inhibited RhoA activity and the phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin, and prevented gastrin-stimulated FAK/paxillin phosphorylation[84]. Thus, MELK may be involved in the formation of peritoneal nodules in GC.

ANGIOGENESIS IN THE GROWTH OF PERITONEAL NODULES

Angiogenesis is a key step in various stages of human cancer development and dissemination[65]. After attachment to the basement membrane, degradation of the ECM and proliferation, the cancer cells induce angiogenesis[85,86]. Previous reports have indicated that the presence of angiogenic factors is an essential event in the development of metastatic nodules in the peritoneum[10]. New vessel formation required for tumor growth is predominantly driven by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), the most potent angiogenic molecule known and the principal target of antiangiogenic therapy (Table 1)[65].

VEGF

Angiogenesis in the subperitoneal space, which is predominantly mediated by VEGF, is an important step in peritoneal dissemination[85]. GC cells that reach the subperitoneal blood vessels proliferate by inducing angiogenesis and finally evolve into massive and firm peritoneal nodules[10,65]. VEGF secreted from cancer cells enhances tumor growth by inducing an angiogenic response in the peritoneal microenvironment, promotes vascular permeability in the peritoneum and contributes to the establishment of peritoneal nodules that generate abundant malignant ascites[87]. Accordingly, VEGF has a central role in the formation of peritoneal dissemination, and the development of antiangiogenic therapy targeting peritoneal mesothelial cells is a promising approach for regulating peritoneal dissemination of GC.

Iroquois homeobox 1

Iroquois homeobox 1 (IRX1) is a member of the Iroquois homeobox protein family and is involved in pattern formation in the embryo[88,89]. Jiang et al[90] first identified the tumor suppressive function of IRX1 in GC. Overexpression of the IRX1 gene is correlated with growth arrest and suppresses peritoneal spreading and long distance metastasis in GC. IRX1 transfection resulted in substantial suppression of peritoneal spreading with reduced angiogenesis (microvessel density) as well as vasculogenic mimicry formation in mouse xenograft models. In addition, the number of blood vessels was significantly reduced by treatment with supernatant from GC cells expressing recombinant IRX1[90]. These findings suggested that IRX1 acts as a growth facilitator of peritoneal nodules in GC via angiogenesis.

MOLECULAR BIOMARKERS

To date, there have been no valid biomarkers indicating the presence of free cancer cells in the abdominal cavity and no confirmed prognostic markers indicating which primary gastric tumors are likely to develop peritoneal dissemination. Improvement in treatment outcomes for GC in the future is dependent on the development of validated biomarkers[17,91-93]. High-performance biomarkers for accurate detection of micrometastasis and prediction of chemosensitivity, including intraperitoneal administration and HIPEC, recurrence and prognosis, will enable personalized therapy[94-98]. Below, several reported candidate biomarkers for peritoneal dissemination in GC are presented.

Carcinoembryonic antigen

Peritoneal lavage cytology has been regarded as the most reliable method for detecting free GC cells; however, it lacks the sensitivity required for detection of residual cancer cells and prediction of peritoneal spread, and it is not uniformly performed in clinical practice[86,99,100]. To address this issue, molecular detection using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis has been proposed as a detection method for micrometastasis in the abdominal cavity. Among the candidate molecular targets, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) has been suggested as a potent molecular marker[101]. We previously demonstrated that detection of CEA mRNA using RT-PCR of peritoneal washes had a high sensitivity and strong correlation with peritoneal recurrence and prognosis after curative surgery. In 242 patients without macroscopic peritoneal dissemination at the point of gastrectomy, positive CEA mRNA was the most important independent variable associated with peritoneal recurrence (hazard ratio = 1.57, P = 0.020)[102]. Moreover, we conducted a phase II clinical trial to evaluate the prognostic impact of postoperative S-1 monotherapy in GC patients with CEA mRNA positivity. As a result, the 3-year survival rate was similar between the study population and the historic control (67.3% vs 67.1%, respectively)[103]. To improve the diagnostic performance for detecting free peritoneal GC cells, a combination of molecular markers with high specificity might be necessary.

Anosmin-1

The Anosmin-1 (ANOS1) gene encodes a cell adhesion protein of the ECM[104]. ANOS1 contains a whey acidic protein domain and three fibronectin III domains, and it promotes the migration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons from the olfactory placode to the hypothalamus during development[105]. ANOS1 induces neurite outgrowth and cell migration through fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signal transduction pathways[106,107].

We recently reported that inhibiting ANOS1 expression decreased the proliferation, invasion and migration of GC cells. Notably, elevated ANOS1 levels in primary GC tissues were significantly associated with larger tumor size, serosal invasion, positive nodal status, and importantly, positive peritoneal lavage cytology[108]. Moreover, ANOS1 concentrations in the sera were lowest in healthy subjects and increased stepwise in patients with localized GC and those with disseminated GC. Thus, ANOS1 can be used to stratify patients according to risk of recurrence[108]. ANOS1 may, therefore, represent a biomarker for progression of GC phenotypes, including peritoneal spreading.

Phosphoglycerate kinase 1

Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1) is an ATP-generating enzyme of the glycolytic pathway and is regulated by HIF-1α[109]. To date, overexpression of PGK1 has been reported in breast and pancreatic cancers, and a close relationship between the regulation of the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and PGK1 was shown in prostate cancer[109]. Zieker et al[14] found a significant overexpression of PGK1, the chemokine CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 in specimens from diffuse-type GC patients who had concomitant peritoneal dissemination. The expression levels of PGK1 were positively correlated with those of the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and HIF-1α but were inversely correlated with VEGF expression[14]. PGK1 expression in the primary tumor may be a candidate biomarker for peritoneal dissemination of GC.

Dihydropyrimidinase-like 3

Dihydropyrimidinase-like 3 (DPYSL3) is a cell-adhesion molecule that is normally expressed in various organs[110,111]. However, recent studies showed that DPYSL3 was involved in metastasis of tumor cells in pancreatic cancer[112]. We recently evaluated the expression levels of DPYSL3 in GC cells and tissues and found that DPYSL3 mRNA expression levels were positively correlated with those of interacting genes (VEGF, FAK and ezrin)[113]. Elevated DPYSL3 expression levels were significantly associated with an aggressive phenotype, including serosal invasion, invasive growth type, and, importantly, positive peritoneal lavage cytology. Tissues from patients with stage IV GC showed increased expression of DPYSL3 mRNA. Consequently, high DPYSL3 mRNA expression in GC tissues was identified as an independent prognostic factor[113]. Although the significance of its expression in sera and ascites fluids has yet to be determined, our results indicated the potential of DPYSL3 as a biomarker of the progression of GC, including peritoneal dissemination.

CONCLUSION

Peritoneal dissemination of GC is a complex and dynamic process comprising several steps and involves diverse molecules acting in a coordinated manner[10,15]. Therefore, attempts to elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for tumor progression in peritoneal dissemination are extremely challenging because the identification of a single pathway does not necessarily indicate that it is the one that determines the prognosis of the disease[114]. In fact, physicians have occasionally found that long-term survivors of peritoneal dissemination of GC are super responders to multimodality treatment, including systemic and intraperitoneal chemotherapy leading to conversion surgery, due to improvement in anticancer agents.

However, most patients are still suffering from uncontrollable disease progression and have a dismal prognosis, indicating that improvement in both diagnostics and treatment is needed. It is necessary to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of peritoneal dissemination formation for the development of molecular targeting agents that can effectively block each step. Sensitive molecular biomarkers can enhance the opportunity to personalize treatment (objectives, timing and procedure), leading to improved outcomes[86].

Although there are still many challenges in the field of research in peritoneal dissemination of GC, the accumulation of molecular biological data is important to improve the management of disseminated GC and overcome this disease in the future.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: March 27, 2016

First decision: May 27, 2016

Article in press: June 15, 2016

P- Reviewer: Kim GH, Kim HH, Park WS S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Kanda M, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Iwata N, Yamada S, Fujii T, Nakayama G, Sugimoto H, Koike M, Nomoto S, et al. Adverse prognostic impact of perioperative allogeneic transfusion on patients with stage II/III gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0456-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartgrink HH, Jansen EP, van Grieken NC, van de Velde CJ. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:477–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen L, Shan YS, Hu HM, Price TJ, Sirohi B, Yeh KH, Yang YH, Sano T, Yang HK, Zhang X, et al. Management of gastric cancer in Asia: resource-stratified guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e535–e547. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439–449. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanda M, Kodera Y, Sakamoto J. Updated evidence on adjuvant treatments for gastric cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:1549–1560. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1094373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, Michiels S, Ohashi Y, Pignon JP, Rougier P, Sakamoto J, Sargent D, Sasako M, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1729–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanda M, Mizuno A, Fujii T, Shimoyama Y, Yamada S, Tanaka C, Kobayashi D, Koike M, Iwata N, Niwa Y, et al. Tumor Infiltrative Pattern Predicts Sites of Recurrence After Curative Gastrectomy for Stages 2 and 3 Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1934–1940. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wadhwa R, Song S, Lee JS, Yao Y, Wei Q, Ajani JA. Gastric cancer-molecular and clinical dimensions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:643–655. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusamura S, Baratti D, Zaffaroni N, Villa R, Laterza B, Balestra MR, Deraco M. Pathophysiology and biology of peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:12–18. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanda M, Sugimoto H, Kodera Y. Genetic and epigenetic aspects of initiation and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10584–10597. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i37.10584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanda M, Sugimoto H, Nomoto S, Oya H, Hibino S, Shimizu D, Takami H, Hashimoto R, Okamura Y, Yamada S, et al. Bcell translocation gene 1 serves as a novel prognostic indicator of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:641–648. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonemura Y, Endo Y, Obata T, Sasaki T. Recent advances in the treatment of peritoneal dissemination of gastrointestinal cancers by nucleoside antimetabolites. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zieker D, Königsrainer I, Tritschler I, Löffler M, Beckert S, Traub F, Nieselt K, Bühler S, Weller M, Gaedcke J, et al. Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 a promoting enzyme for peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1513–1520. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurashige J, Mima K, Sawada G, Takahashi Y, Eguchi H, Sugimachi K, Mori M, Yanagihara K, Yashiro M, Hirakawa K, et al. Epigenetic modulation and repression of miR-200b by cancer-associated fibroblasts contribute to cancer invasion and peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:133–141. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim B, Kim C, Kim JH, Kwon WS, Lee WS, Kim JM, Park JY, Kim HS, Park KH, Kim TS, et al. Genetic alterations and their clinical implications in gastric cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis revealed by whole-exome sequencing of malignant ascites. Oncotarget. 2016;7:8055–8066. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang BG, Kim WH. Molecular pathology of gastric carcinoma. Pathobiology. 2011;78:302–310. doi: 10.1159/000321703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resende C, Thiel A, Machado JC, Ristimäki A. Gastric cancer: basic aspects. Helicobacter. 2011;16 Suppl 1:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanda M, Murotani K, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Yamada S, Fujii T, Nakayama G, Sugimoto H, Koike M, Fujiwara M, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 alters recurrence patterns and prognostic factors among patients with stage II/III gastric cancer: A propensity score matching analysis. Surgery. 2015;158:1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miao ZF, Wang ZN, Zhao TT, Xu YY, Gao J, Miao F, Xu HM. Peritoneal milky spots serve as a hypoxic niche and favor gastric cancer stem/progenitor cell peritoneal dissemination through hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Stem Cells. 2014;32:3062–3074. doi: 10.1002/stem.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Chu KM. E-cadherin and gastric cancer: cause, consequence, and applications. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:637308. doi: 10.1155/2014/637308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng W, Zhu J, Shan L, Han Z, Aerxiding P, Quhai A, Zeng F, Wang Z, Li H. The clinicopathological significance of CDH1 in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:2149–2157. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S75429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ezaka K, Kanda M, Sugimoto H, Shimizu D, Oya H, Nomoto S, Sueoka S, Tanaka Y, Takami H, Hashimoto R, et al. Reduced Expression of Adherens Junctions Associated Protein 1 Predicts Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Curative Hepatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S1499–S1507. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng Z, Wang CX, Fang EH, Wang GB, Tong Q. Role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer initiation and progression. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5403–5410. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka H, Kanda M, Koike M, Iwata N, Shimizu D, Ezaka K, Sueoka S, Tanaka Y, Takami H, Hashimoto R, et al. Adherens junctions associated protein 1 serves as a predictor of recurrence of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Int J Oncol. 2015;47:1811–1818. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo Y, Yin J, Zha L, Wang Z. Clinicopathological significance of platelet-derived growth factor B, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β, and E-cadherin expression in gastric carcinoma. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2013;17:150–155. doi: 10.5114/wo.2013.34618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerke V, Moss SE. Annexins: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:331–371. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim LH, Pervaiz S. Annexin 1: the new face of an old molecule. FASEB J. 2007;21:968–975. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7464rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perretti M, D’Acquisto F. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:62–70. doi: 10.1038/nri2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng TY, Wu MS, Lin JT, Lin MT, Shun CT, Huang HY, Hua KT, Kuo ML. Annexin A1 is associated with gastric cancer survival and promotes gastric cancer cell invasiveness through the formyl peptide receptor/extracellular signal-regulated kinase/integrin beta-1-binding protein 1 pathway. Cancer. 2012;118:5757–5767. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salehi AH, Roux PP, Kubu CJ, Zeindler C, Bhakar A, Tannis LL, Verdi JM, Barker PA. NRAGE, a novel MAGE protein, interacts with the p75 neurotrophin receptor and facilitates nerve growth factor-dependent apoptosis. Neuron. 2000;27:279–288. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du Q, Zhang Y, Tian XX, Li Y, Fang WG. MAGE-D1 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:659–665. doi: 10.3892/or_00000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu D, Kanda M, Sugimoto H, Sueoka S, Takami H, Ezaka K, Tanaka Y, Hashimoto R, Okamura Y, Iwata N, et al. NRAGE promotes the malignant phenotype of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1847–1854. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Gao X, Xu Y. MAGED1: molecular insights and clinical implications. Ann Med. 2011;43:347–355. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.573806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Q, Ou C, Liu M, Xiao W, Wen C, Sun F. NRAGE promotes cell proliferation by stabilizing PCNA in a ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in esophageal carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1643–1651. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chu CS, Xue B, Tu C, Feng ZH, Shi YH, Miao Y, Wen CJ. NRAGE suppresses metastasis of melanoma and pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2007;250:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanda M, Shimizu D, Fujii T, Tanaka H, Tanaka Y, Ezaka K, Shibata M, Takami H, Hashimoto R, Sueoka S, et al. Neurotrophin Receptor-interacting Melanoma Antigen-encoding Gene Homolog Is Associated with Malignant Phenotype of Gastric Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5375-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyake S, Kitajima Y, Nakamura J, Kai K, Yanagihara K, Tanaka T, Hiraki M, Miyazaki K, Noshiro H. HIF-1α is a crucial factor in the development of peritoneal dissemination via natural metastatic routes in scirrhous gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2013;43:1431–1440. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanda M, Shimizu D, Nomoto S, Hibino S, Oya H, Takami H, Kobayashi D, Yamada S, Inokawa Y, Tanaka C, et al. Clinical significance of expression and epigenetic profiling of TUSC1 in gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:136–144. doi: 10.1002/jso.23614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janjigian YY, Kelsen DP. Genomic dysregulation in gastric tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:237–242. doi: 10.1002/jso.23263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Razzak M. Genetics: new molecular classification of gastric adenocarcinoma proposed by The Cancer Genome Atlas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:499. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang D, Li T, Li X, Zhang L, Sun L, He X, Zhong X, Jia D, Song L, Semenza GL, et al. HIF-1-mediated suppression of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases and fatty acid oxidation is critical for cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1930–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semenza GL. HIF-1 mediates metabolic responses to intratumoral hypoxia and oncogenic mutations. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3664–3671. doi: 10.1172/JCI67230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Cristofano A, Pandolfi PP. The multiple roles of PTEN in tumor suppression. Cell. 2000;100:387–390. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koul D, Jasser SA, Lu Y, Davies MA, Shen R, Shi Y, Mills GB, Yung WK. Motif analysis of the tumor suppressor gene MMAC/PTEN identifies tyrosines critical for tumor suppression and lipid phosphatase activity. Oncogene. 2002;21:2357–2364. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008;133:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davidson L, Maccario H, Perera NM, Yang X, Spinelli L, Tibarewal P, Glancy B, Gray A, Weijer CJ, Downes CP, et al. Suppression of cellular proliferation and invasion by the concerted lipid and protein phosphatase activities of PTEN. Oncogene. 2010;29:687–697. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang LL, Liu J, Lei S, Zhang J, Zhou W, Yu HG. PTEN inhibits the invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer via downregulation of FAK expression. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Müller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lippitz BE. Cytokine patterns in patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e218–e228. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70582-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Domanska UM, Kruizinga RC, Nagengast WB, Timmer-Bosscha H, Huls G, de Vries EG, Walenkamp AM. A review on CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in oncology: no place to hide. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Izumi D, Ishimoto T, Miyake K, Sugihara H, Eto K, Sawayama H, Yasuda T, Kiyozumi Y, Kaida T, Kurashige J, et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 activation by cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes integrin β1 clustering and invasiveness in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1207–1219. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen G, Chen SM, Wang X, Ding XF, Ding J, Meng LH. Inhibition of chemokine (CXC motif) ligand 12/chemokine (CXC motif) receptor 4 axis (CXCL12/CXCR4)-mediated cell migration by targeting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway in human gastric carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12132–12141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.302299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koizumi K, Hojo S, Akashi T, Yasumoto K, Saiki I. Chemokine receptors in cancer metastasis and cancer cell-derived chemokines in host immune response. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1652–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasumoto K, Koizumi K, Kawashima A, Saitoh Y, Arita Y, Shinohara K, Minami T, Nakayama T, Sakurai H, Takahashi Y, et al. Role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2181–2187. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duda DG, Kozin SV, Kirkpatrick ND, Xu L, Fukumura D, Jain RK. CXCL12 (SDF1alpha)-CXCR4/CXCR7 pathway inhibition: an emerging sensitizer for anticancer therapies? Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2074–2080. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Debnath B, Xu S, Grande F, Garofalo A, Neamati N. Small molecule inhibitors of CXCR4. Theranostics. 2013;3:47–75. doi: 10.7150/thno.5376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yasumoto K, Yamada T, Kawashima A, Wang W, Li Q, Donev IS, Tacheuchi S, Mouri H, Yamashita K, Ohtsubo K, et al. The EGFR ligands amphiregulin and heparin-binding egf-like growth factor promote peritoneal carcinomatosis in CXCR4-expressing gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3619–3630. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamada M, Ichikawa Y, Yamagishi S, Momiyama N, Ota M, Fujii S, Tanaka K, Togo S, Ohki S, Shimada H. Amphiregulin is a promising prognostic marker for liver metastases of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2351–2356. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tokumaru S, Higashiyama S, Endo T, Nakagawa T, Miyagawa JI, Yamamori K, Hanakawa Y, Ohmoto H, Yoshino K, Shirakata Y, et al. Ectodomain shedding of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands is required for keratinocyte migration in cutaneous wound healing. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:209–220. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanda M, Oya H, Nomoto S, Takami H, Shimizu D, Hashimoto R, Sueoka S, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Yamada S, et al. Diversity of clinical implication of B-cell translocation gene 1 expression by histopathologic and anatomic subtypes of gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1256–1264. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu J, Ma L, Xu J, Liu C, Zhang J, Liu J, Chen R, Zhou Y. Spheroid body-forming cells in the human gastric cancer cell line MKN-45 possess cancer stem cell properties. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:453–459. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chiang AC, Massagué J. Molecular basis of metastasis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2814–2823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0805239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hood JD, Cheresh DA. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrc727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jin H, Varner J. Integrins: roles in cancer development and as treatment targets. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:561–565. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nishimori H, Yasoshima T, Denno R, Shishido T, Hata F, Okada Y, Ura H, Yamaguchi K, Isomura H, Sato N, et al. A novel experimental mouse model of peritoneal dissemination of human gastric cancer cells: different mechanisms in peritoneal dissemination and hematogenous metastasis. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:715–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takatsuki H, Komatsu S, Sano R, Takada Y, Tsuji T. Adhesion of gastric carcinoma cells to peritoneum mediated by alpha3beta1 integrin (VLA-3) Cancer Res. 2004;64:6065–6070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brinckerhoff CE, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: a tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nrm763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hadler-Olsen E, Winberg JO, Uhlin-Hansen L. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer: their value as diagnostic and prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2041–2051. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imai K, Yokohama Y, Nakanishi I, Ohuchi E, Fujii Y, Nakai N, Okada Y. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 (matrilysin) from human rectal carcinoma cells. Activation of the precursor, interaction with other matrix metalloproteinases and enzymic properties. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6691–6697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Soleyman-Jahi S, Nedjat S, Abdirad A, Hoorshad N, Heidari R, Zendehdel K. Prognostic significance of matrix metalloproteinase-7 in gastric cancer survival: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;10:e0122316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ii M, Yamamoto H, Adachi Y, Maruyama Y, Shinomura Y. Role of matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin) in human cancer invasion, apoptosis, growth, and angiogenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:20–27. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yonemura Y, Endou Y, Fujita H, Fushida S, Bandou E, Taniguchi K, Miwa K, Sugiyama K, Sasaki T. Role of MMP-7 in the formation of peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:63–70. doi: 10.1007/pl00011698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brigstock DR. Regulation of angiogenesis and endothelial cell function by connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and cysteine-rich 61 (CYR61) Angiogenesis. 2002;5:153–165. doi: 10.1023/a:1023823803510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang MH, Lin BR, Chang CH, Chen ST, Lin SK, Kuo MY, Jeng YM, Kuo ML, Chang CC. Connective tissue growth factor modulates oral squamous cell carcinoma invasion by activating a miR-504/FOXP1 signalling. Oncogene. 2012;31:2401–2411. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shakunaga T, Ozaki T, Ohara N, Asaumi K, Doi T, Nishida K, Kawai A, Nakanishi T, Takigawa M, Inoue H. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in cartilaginous tumors. Cancer. 2000;89:1466–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen CN, Chang CC, Lai HS, Jeng YM, Chen CI, Chang KJ, Lee PH, Lee H. Connective tissue growth factor inhibits gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis by blocking integrin α3β1-dependent adhesion. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:504–515. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heyer BS, Warsowe J, Solter D, Knowles BB, Ackerman SL. New member of the Snf1/AMPK kinase family, Melk, is expressed in the mouse egg and preimplantation embryo. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;47:148–156. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199706)47:2<148::AID-MRD4>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Davezac N, Baldin V, Blot J, Ducommun B, Tassan JP. Human pEg3 kinase associates with and phosphorylates CDC25B phosphatase: a potential role for pEg3 in cell cycle regulation. Oncogene. 2002;21:7630–7641. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hebbard LW, Maurer J, Miller A, Lesperance J, Hassell J, Oshima RG, Terskikh AV. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase is upregulated and required in mammary tumor-initiating cells in vivo. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8863–8873. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kig C, Beullens M, Beke L, Van Eynde A, Linders JT, Brehmer D, Bollen M. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) reduces replication stress in glioblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:24200–24212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.471433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 84.Du T, Qu Y, Li J, Li H, Su L, Zhou Q, Yan M, Li C, Zhu Z, Liu B. Maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase enhances gastric cancer progression via the FAK/Paxillin pathway. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:100. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yan Y, Wang LF, Wang RF. Role of cancer-associated fibroblasts in invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9717–9726. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i33.9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kanda M, Kodera Y. Recent advances in the molecular diagnostics of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9838–9852. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.9838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Javle M, Smyth EC, Chau I. Ramucirumab: successfully targeting angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5875–5881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guo X, Liu W, Pan Y, Ni P, Ji J, Guo L, Zhang J, Wu J, Jiang J, Chen X, et al. Homeobox gene IRX1 is a tumor suppressor gene in gastric carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:3908–3920. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Y, Yu Y, Zhu Z, Xu H, Ji J, Bu L, Liu B, Jiang H, Lin Y, Kong X, et al. Identification of a new target region by loss of heterozygosity at 5p15.33 in sporadic gastric carcinomas: genotype and phenotype related. Cancer Lett. 2005;224:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jiang J, Liu W, Guo X, Zhang R, Zhi Q, Ji J, Zhang J, Chen X, Li J, Zhang J, et al. IRX1 influences peritoneal spreading and metastasis via inhibiting BDKRB2-dependent neovascularization on gastric cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:4498–4508. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kanda M, Shimizu D, Tanaka H, Shibata M, Iwata N, Hayashi M, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Yamada S, Fujii T, et al. Metastatic pathway-specific transcriptome analysis identifies MFSD4 as a putative tumor suppressor and biomarker for hepatic metastasis in patients with gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:13667–13679. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yasui W, Sentani K, Sakamoto N, Anami K, Naito Y, Oue N. Molecular pathology of gastric cancer: research and practice. Pathol Res Pract. 2011;207:608–612. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lin LL, Huang HC, Juan HF. Discovery of biomarkers for gastric cancer: a proteomics approach. J Proteomics. 2012;75:3081–3097. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kanda M, Knight S, Topazian M, Syngal S, Farrell J, Lee J, Kamel I, Lennon AM, Borges M, Young A, et al. Mutant GNAS detected in duodenal collections of secretin-stimulated pancreatic juice indicates the presence or emergence of pancreatic cysts. Gut. 2013;62:1024–1033. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Graziosi L, Mencarelli A, Renga B, Santorelli C, Cantarella F, Bugiantella W, Cavazzoni E, Donini A, Fiorucci S. Gene expression changes induced by HIPEC in a murine model of gastric cancer. In Vivo. 2012;26:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kanda M, Sadakari Y, Borges M, Topazian M, Farrell J, Syngal S, Lee J, Kamel I, Lennon AM, Knight S, et al. Mutant TP53 in duodenal samples of pancreatic juice from patients with pancreatic cancer or high-grade dysplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:719–30.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang XL, Shi HJ, Wang JP, Tang HS, Wu YB, Fang ZY, Cui SZ, Wang LT. MicroRNA-218 is upregulated in gastric cancer after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy and increases chemosensitivity to cisplatin. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11347–11355. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kanda M, Shimizu D, Nomoto S, Takami H, Hibino S, Oya H, Hashimoto R, Suenaga M, Inokawa Y, Kobayashi D, et al. Prognostic impact of expression and methylation status of DENN/MADD domain-containing protein 2D in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kanda M, Nomoto S, Oya H, Hashimoto R, Takami H, Shimizu D, Sonohara F, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Yamada S, et al. Decreased expression of prenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2 correlates with reduced survival of patients with gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33:88. doi: 10.1186/s13046-014-0088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Durães C, Almeida GM, Seruca R, Oliveira C, Carneiro F. Biomarkers for gastric cancer: prognostic, predictive or targets of therapy? Virchows Arch. 2014;464:367–378. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1533-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jeon CH, Kim IH, Chae HD. Prognostic value of genetic detection using CEA and MAGE in peritoneal washes with gastric carcinoma after curative resection: result of a 3-year follow-up. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e83. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kodera Y, Nakanishi H, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Ohashi N, Yamamura Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Tatematsu M, Nakao A. Prognostic significance of intraperitoneal cancer cells in gastric carcinoma: analysis of real time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction after 5 years of followup. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ito S, Kodera Y, Mochizuki Y, Kojima T, Nakanishi H, Yamamura Y. Phase II clinical trial of postoperative S-1 monotherapy for gastric cancer patients with free intraperitoneal cancer cells detected by real-time RT-PCR. World J Surg. 2010;34:2083–2089. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0573-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tanaka Y, Kanda M, Sugimoto H, Shimizu D, Sueoka S, Takami H, Ezaka K, Hashimoto R, Okamura Y, Iwata N, et al. Translational implication of Kallmann syndrome-1 gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:2546–2554. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Choy CT, Kim H, Lee JY, Williams DM, Palethorpe D, Fellows G, Wright AJ, Laing K, Bridges LR, Howe FA, et al. Anosmin-1 contributes to brain tumor malignancy through integrin signal pathways. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:85–99. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.González-Martínez D, Kim SH, Hu Y, Guimond S, Schofield J, Winyard P, Vannelli GB, Turnbull J, Bouloux PM. Anosmin-1 modulates fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signaling in human gonadotropin-releasing hormone olfactory neuroblasts through a heparan sulfate-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10384–10392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3400-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu J, Cao W, Chen W, Xu L, Zhang C. Decreased expression of Kallmann syndrome 1 sequence gene (KAL1) contributes to oral squamous cell carcinoma progression and significantly correlates with poorly differentiated grade. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44:109–114. doi: 10.1111/jop.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kanda M, Shimizu D, Fujii T, Sueoka S, Tanaka Y, Ezaka K, Takami H, Tanaka H, Hashimoto R, Iwata N, et al. Function and diagnostic value of Anosmin-1 in gastric cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:721–730. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang J, Wang J, Dai J, Jung Y, Wei CL, Wang Y, Havens AM, Hogg PJ, Keller ET, Pienta KJ, et al. A glycolytic mechanism regulating an angiogenic switch in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:149–159. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Oya H, Kanda M, Sugimoto H, Shimizu D, Takami H, Hibino S, Hashimoto R, Okamura Y, Yamada S, Fujii T, et al. Dihydropyrimidinase-like 3 is a putative hepatocellular carcinoma tumor suppressor. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:590–600. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0993-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fukada M, Watakabe I, Yuasa-Kawada J, Kawachi H, Kuroiwa A, Matsuda Y, Noda M. Molecular characterization of CRMP5, a novel member of the collapsin response mediator protein family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37957–37965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kawahara T, Hotta N, Ozawa Y, Kato S, Kano K, Yokoyama Y, Nagino M, Takahashi T, Yanagisawa K. Quantitative proteomic profiling identifies DPYSL3 as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma-associated molecule that regulates cell adhesion and migration by stabilization of focal adhesion complex. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kanda M, Nomoto S, Oya H, Shimizu D, Takami H, Hibino S, Hashimoto R, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Yamada S, et al. Dihydropyrimidinase-like 3 facilitates malignant behavior of gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33:66. doi: 10.1186/s13046-014-0066-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kanda M, Nomoto S, Oya H, Takami H, Shimizu D, Hibino S, Hashimoto R, Kobayashi D, Tanaka C, Yamada S, et al. The Expression of Melanoma-Associated Antigen D2 Both in Surgically Resected and Serum Samples Serves as Clinically Relevant Biomarker of Gastric Cancer Progression. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23 Suppl 2:S214–S221. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]