Abstract

Oncogenic events combined with a favourable environment are the two main factors in the oncological process. The tumour microenvironment is composed of a complex, interconnected network of protagonists, including soluble factors such as cytokines, extracellular matrix components, interacting with fibroblasts, endothelial cells, immune cells and various specific cell types depending on the location of the cancer cells (e.g. pulmonary epithelium, osteoblasts). This diversity defines specific “niches” (e.g. vascular, immune, bone niches) involved in tumour growth and the metastatic process. These actors communicate together by direct intercellular communications and/or in an autocrine/paracrine/endocrine manner involving cytokines and growth factors. Among these glycoproteins, RANKL (receptor activator nuclear factor-κB ligand) and its receptor RANK (receptor activator nuclear factor), members of the TNF and TNFR superfamilies, have stimulated the interest of the scientific community. RANK is frequently expressed by cancer cells in contrast with RANKL which is frequently detected in the tumour microenvironment and together they participate in every step in cancer development. Their activities are markedly regulated by osteoprotegerin (OPG, a soluble decoy receptor) and its ligands, and by LGR4, a membrane receptor able to bind RANKL. The aim of the present review is to provide an overview of the functional implication of the RANK/RANKL system in cancer development, and to underline the most recent clinical studies.

Keywords: microenvironment, oncogenesis, RANK, RANKL

INTRODUCTION

In a physiological context, a healthy tissue microenvironment provides an adapted 3D microarchitecture with essential intercellular signalling, thus ensuring appropriate function. This tissue homoeostasis acts as a barrier to tumour development by inhibiting excessive cell growth and/or migration. Indeed, this fragile equilibrium can be destabilized by any alterations to cell communications, or interaction between cells and extracellular matrix components and consequently can become a fertile environment for cancer cells, promoting their malignant transformation and their proliferation [1]. The conjunction between one or more oncogenic events and this fertile environment can lead to the development of a tumour mass, which is frequently linked to the tumour cells escaping from the immune system [2]. In fact, this description reflects the “seed and soil” theory proposed by Stephan Paget in 1889 to explain preferential metastatic sites depending on tumour subtype [3].

This “soil” or tumour microenvironment is a very complex and dynamic organization, defined by three main “niches” depending on their functional implication: (i) an immune niche involved in local immune tolerance, (ii) a vascular niche associated with tumour cell extravasation/migration and (iii) a metastatic niche (e.g. bone, lung, liver) hosting the metastastic tumour cells [4,5]. The notion of tumour niche was initially described for haematopoietic stem cells, for which the bone microenvironment is composed of complex signalling pathways that carefully regulate stem cell renewal, differentiation and quiescence [6]. The concept of tumour niche was then extended to bone metastases, such as breast or prostate cancers [7–9]. Lu et al. [10] described a model of bone metastasis dormancy in breast cancer where VCAM-1, aberrantly expressed, promoted the transition from indolent micrometastasis to proliferating tumour by recruiting and activating in situ osteoclastic cells. More recently, Wang et al. [11] analysed the distribution of human prostate cancer cell lines colonizing mouse bones after intracardiac injection of tumour cells and demonstrated that homing of prostate cancer cells was associated with the presence of activated osteoblast lineage cells. These two recent manuscripts are perfect examples of the involvement of the tumour environment in the biology of bone metastases.

The tumour microenvironment thus provides all the factors necessary for cancer cell survival, dormancy, proliferation or/and migration [10] and very often, tumour cells divert this environment in their favour [7–9]. Indeed, this specific microenvironment has recently been involved in the maintenance of cancer cell dormancy [12–14] and may also play a part in drug resistance mechanisms by controlling the balance between cell proliferation and cell death, or by secreting soluble factors that dysregulate the cell cycle checkpoints, the cell death associated signalling pathways, or drug efflux [15,16].

Cell communications in physiological and pathological conditions are promoted by physical contacts involving adhesion molecules and channels, but also by a very high number of soluble mediators called cytokines and growth factors which appear to be the key protagonists in the dialogue established between cancer cells and their microenvironment [16]. These polypeptidic mediators perform their activities in an autocrine, paracrine or juxtacrine manner leading to inflammatory foci and the establishment of a vicious cycle between cancer cells and their local niches [17–19]. These proteins also have endocrine activities and contribute in this way to both the formation of a chemoattractant gradient and the metastatic process.

Considerable diversity in the cytokines and growth factors playing a role in cancer development has been identified in the last four decades. Some of them can be considered to be biological markers for aggressiveness, or to be prognostic factors, whereas others are also regarded as therapeutic targets. Among cytokine families, in the last 15 years, the biology of receptor activator nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) and its receptor RANK has been widely studied in cancer [20–23] and has been identified as a key therapeutic target in numerous cancer entities, as described below. The present review gives a synthesis of RANK/RANKL pathway involvement in the carcinogenesis process. Their direct or indirect activities in oncogenic events will be described, as will their recent therapeutic applications.

RANKL/RANK SYSTEM: DISCOVERY, MOLECULAR AND FUNCTIONAL CHARACTERIZATION

The superfamily of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) is composed of more than 40 members and is associated with a similar number of membrane or soluble receptors. RANKL is one member of the TNF-α superfamily (TNFSF11) and binds to a membrane receptor named receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK), a member of the TNF receptor superfamily (TNFRSF11A) [20–30]. The interactions between RANKL and RANK lead to specific intracellular signal transduction and are controlled by a decoy receptor called osteoprotegerin (OPG) (TNFRSF11B) [27] (Figure 1).

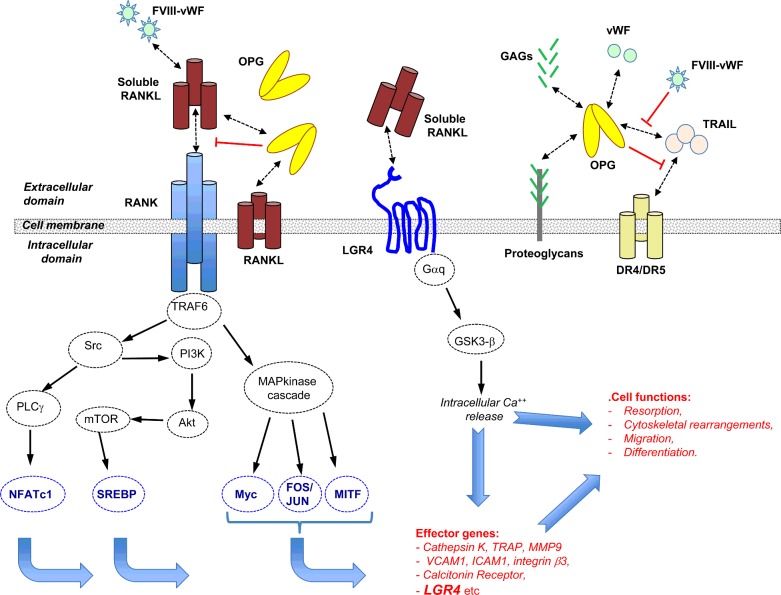

Figure 1. RANK/RANKL signalling in cancer cells: a very complex molecular network.

RANKL is a trimeric complex produced in a membrane or soluble form. Secreted RANKL can be produced from a specific transcript or by proteolysis of its membrane form. Trimeric RANKL interacts with a trimeric receptor named RANK and triggers a signalling cascade controlling the transcription of numerous effector genes. Additional protagonists intervene to regulate the binding of RANKL to RANK. In this way, OPG acts as a decoy receptor interacting with RANKL, and complex VIII (FVIII-vWF) showed a similar capacity. However, OPG is itself controlled by many ligands, including TRAIL, vWF and glycoaminoglycans (GAGs), and the final inhibitory effect of OPG on RANKL is dependent on its binding to these ligands. Very recently, it has been demonstrated that LGR4 is a new receptor for RANKL which can counterbalance the RANKL activities transmitted by RANK signalling.

RANKL

RANKL has alternatively been called tumour necrosis factor-related activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE) [26], osteoprotegerin ligand (OPGL) [27,28] and osteoclastic differentiation factor (ODF) [29,30]. Although RANKL is the name commonly used, the official nomenclature of this cytokine is TNFSF11. RANKL is a homotrimeric type II membrane protein with no signal peptide and existing in three isoforms due to alternative splicing of the same gene [31]. Among these isoforms, the full-length RANKL is called RANKL1, RANKL2 is a shorter form of RANKL1 in which a part of the intra-cytoplasmic domain is missing and RANKL 3 is a soluble form of RANKL, with the N-terminal part of the amino acids deleted [31]. A soluble RANKL can also result from the sheding of membrane-RANKL induced by various enzymes such as the metalloproteinase disintegrin TNF-α converting enzyme (TACE) [32] or ADAM-10, MMP-7, MMP-14 [33,34]. RANKL is expressed by a wide variety of tissues such as the brain, skin, intestine, skeletal muscle, kidney, liver, lung and mammary tissue, but is more highly expressed in bone tissue [35], lymphoid organs and the vascular system [36]. The control of bone remodelling is the predominant function of RANKL. Indeed, RANKL effectively regulates the bone resorption process by stimulating osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast survival [37,38]. Whether RANKL is expressed by osteoblasts, osteocytes, chondrocytes or stromal cells, osteocytes are its main source in adult bone [39,40]. The role of RANKL is not restricted to the bone tissue and RANKL also plays an important role in the immune system, increasing the ability of dendritic cells to stimulate both naive T-cell proliferation and the survival of RANK+ T-cells [25,26,41]. In this context, Wong et al. [27] demonstrated that RANKL is a specific survival factor for dendritic cells. Overall, RANKL is one of the key factors at the crossroad between bones and immunity, a topic called “osteoimmunology” [42].

RANK

RANK, also known as TRANCE receptor [43] and TNFRSF11A, is the signalling receptor for RANKL [25]. RANK belongs to the TNF superfamily receptors and is a type I transmembrane protein. This receptor has a large cytoplasmic domain at its C-terminal domain, a N-terminal extracellular domain with four cystein-rich repeat motifs and two N-glycosylation sites [21]. Its last domain is involved in the interaction with RANKL and the induction of the receptor's trimerization [44,45]. RANK mRNAs have been detected in many tissues such as the thymus, mammary glands, liver and prostate, but more significantly in bone [21,25]. By transducing the cell signalling initiated by RANKL, RANK plays a part in controlling bone remodelling and immunity [46,47]. Its functional activities have been clearly established by studying the phenotype of RANK knockout mice which exhibit severe osteopetrosis, with a lack of mature osteoclasts, and an absence of lymph node development with impairment in B- and T-cell maturation [48,49]. RANK is then the second key protagonist of “osteoimmunology” [50].

RANK/RANKL AND CANCER

RANK expression identifies cancer cells as RANKL targets

The expression of RANK/RANKL is not restricted to healthy tissues and numerous studies have demonstrated their expression in neoplastic tissues. This wide distribution strengthens the hypothesis of their key role in the oncogenic process (Table 1). Thus, a high percentage of carcinoma cells express RANK mRNA/protein at various levels [51,52]. Indeed, 89% of all the carcinomas assessed exhibit RANK positive immunostaining, and approximately 60% of cases showed more than 50% of positive cancer cells. Interestingly, RANK expression in carcinoma cells is a poor prognostic marker as demonstrated in breast cancer [86,87]. Similarly to prostate cancers, Pfitzner et al. [87] demonstrated that higher RANK expression in the primary breast tumour was associated with higher sensitivity to chemotherapy, but also a higher risk of relapse and death despite this higher sensitivity. RANK expression was also described as being predictive of poor prognosis in bone metastatic patients but not in patients with visceral metastases [88]. Similarly, sarcoma cells also express RANK (18–69% depending on the series) [79,89,90] and expression is correlated with clinical parameters. Trieb and Windhager [89] described a reverse correlation between RANK expression and the overall survival of patients with osteosarcoma, but not with the response to chemotherapy. These authors observed lower disease-free and overall survival rates in patients presenting RANK positive tumours. Bago-Horvath et al. revealed that RANKL expression was significantly more common in osteosarcoma of the lower extremity than in any other location and did not find any significant correlation between RANKL and disease-free or osteosarcoma-specific survival. However, they did report that RANK expression is a negative prognostic factor regarding disease-free survival, confirming the data obtained by Trieb and Windehager [89]. Interestingly, in 2012, Papanastasiou et al. [91] identified a new isoform of RANK (named RANK-c) generated by alternative splicing and expressed in breast cancer samples. Its expression was reversely correlated with histological grade and RANK-c was able to inhibit cell motility and the migration of breast cancer cells by interfering with RANK signalling.

Table 1. RANK and RANKL expression in cancers.

| Cancer subtypes or related organ | RANK expressing tumours (references) | RANKL expressing tumours (references) |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder carcinoma | [51] | – |

| Breast carcinoma | [51–56] | [57–60] |

| Cervical cancer | [51,61] | [61] |

| Chondrosarcoma | [62] | [62,63] |

| Colon and rectal cancers | [51] | – |

| Endometrial tumours | [51] | – |

| Oesophageal tumours | [51,64] | – |

| Giant cell tumours of bone | [65] | [63–66] |

| Hepatocarcinoma | [51,67] | [67,68] |

| Lung cancer | [51,69] | [69] |

| Lymphoma | [51,70] | [71,72] |

| Melanoma | [73,74] | – |

| Myeloma | [75] | [75,76] |

| Neuroblastoma | [51] | [77] |

| Oral squamous carcinoma | [78] | [78] |

| Osteosarcoma | [63,79] | [63,79,80] |

| Prostate carcinoma | [51,73,81,82] | [81,83] |

| Renal carcinoma | [84] | [84] |

| Thymic tumours | [51] | – |

| Thyroid adenocarcinoma | [51,85] | [85] |

In several studies [87,90], RANKL expression was not correlated with any clinical outcomes in either carcinoma or sarcoma. However, in one series of 40 patients, Lee et al. [92] showed that RANKL expression was related to poor response to preoperative chemotherapy and a high RANKL level was associated with inferior survival. Recently, Cathomas et al. [93] described an interesting clinical case of an osteosarcoma patient treated with sorafenib and denosumab. RANK and RANKL were expressed by the tumour cells and the authors observed complete metabolic remission for over 18 months strengthening the potential therapeutic value of blocking RANK/RANKL signalling in osteosarcoma [93]. Whereas RANK is expressed by various cancer cell types, its ligand can be produced either by tumour cells or by their environment (Table 1). Consequently, RANKL can then act in a paracrine or autocrine manner on cancer cells. The best example of such paracrine activity is given by the role of RANK/RANKL in the pathogenesis of giant cell tumours in bone. RANK is expressed by giant osteoclasts and the macrophagic component of the tumours, whereas RANKL is produced by stromal cells. Furthermore, exacerbated production of RANKL by stromal cells is directly associated with an increase in osteoclastogenesis and bone destruction [94]. This observation identifies the giant cell tumours in bone as very good candidates for the clinical use of Denosumab [95].

Direct RANK/RANKL signalling in cancer cells: the regulatory activities of OPG and LGR4

RANK, like the other receptors in the TNF receptor superfamily, is characterized by the absence of tyrosine kinase activity and consequently requires adapter proteins named TNF-receptor associated factor (TRAF) in order to transmit cell signalling. The intracellular domain of RANK has two TRAF binding sites able to interact with TRAF-2, -3, -5 and -6 [96,97], but only TRAF6 mutations led to an osteopetrotic phenotype similar to the phenotype of RANK knockout mice, thus underlining the predominant role of TRAF6 in RANK associated signalling among the TRAF family members [96–101]. Consecutively, TRAF6 leads to the activation of Src/PLCγ, PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK (p38, JNK, ERK1/2) cascades which result in the translocation of transcriptional activators including NF-κB, Fos/Jun or MITF and subsequently to the transcription of numerous effector genes involved in bone resorption such as cathepsin K or TRAP, in cell adhesion and motility such as VCAM1 or ICAM1. This explains the various functional impacts that RANKL has on normal and cancer cells (Figure 1).

The first identified regulator of RANKL activities was a soluble protein named OPG [102,103]. OPG is considered to be a ubiquitous protein with predominant expression in bone (osteoblasts, mesenchymal stem cells), immune cells (dendritic cells, T- and B-cells) and vessels (endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells) [21,104]. OPG acts as a decoy receptor for RANKL, and blocks the RANK–RANKL interaction and RANKL-induced signalling pathways with its N-terminal [11,89]. OPG and RANKL expression are both regulated by inflammatory cytokines released into the microenvironment of cancer cells, and RANKL activities will result from the level of expression and the kinetics of both factors in this microenvironment [21,105]. OPG binds to soluble and membrane RANKL and strongly controls RANKL bioavailability at the cell membrane by facilitating its internalization and reducing its half-life [106]. However, OPG possesses numerous other ligands which markedly regulate its expression and have an impact on RANKL availability (Figure 1) [104]. In this way, OPG binds to glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans such as syndecan-1 through its heparin-binding domain with a strong influence on cancer cell development [104,107]. The best illustration of the functional consequence of this interaction in cancer is given by myeloma cells which overexpress syndecan-1 [108]. OPG produced in the bone microenvironment is trapped, internalized and degraded by myeloma cells and the OPG/RANKL balance is then dysregulated in favour of RANKL. The OPG/RANKL imbalance leads to bone resorption, a phenomenon exacerbated by the RANKL production of the myeloma cells. By sequestering OPG, myeloma cells elaborate a microenvironment that facilitates their expansion. Similarly, OPG can be trapped by the proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans located in the extracellular matrix as shown in osteosarcoma [109]. In addition, OPG binds TRAIL (TNF related apoptosis inducing ligand), a key natural pro-apoptotic and “anti-cancer” factor [110]. By this way, OPG can thus act as an anti-apoptotic and a pro-proliferative factor for cancer cells by blocking TRAIL activity, as shown with prostate carcinoma for instance [111]. Complex VIII (factor VIII-von Willebrand factor) is also able to bind to OPG and increases the complexity of this system by regulating TRAIL-induced cancer cell death [112]. Finally, RANKL expressed by the tumour cells or/and their environment by exerting its action through RANK in an autocrine, endocrine or paracrine manner contributes to establishing the fertile soil needed for tumour cells to be maintained and proliferate. In this picture, OPG and its ligands are notably involved in the bioavailability and biological activities of RANKL.

Very recently, a new RANKL receptor named leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 4 (LRG4) characterized by seven transmembrane regions, has been identified [113]. In this work, Luo et al. [113] revealed that RANKL binds to the extracellular domain of LGR4 and by this way negatively regulates osteoclastogenesis through activation of Gαq/GS3K-β signalling and repression of the NFATc1 pathway (Figure 1). Moreover, Lgr4 is a transcriptional target of the canonical RANKL–NFATc1, which shows that LGR4 signalling acts as the feedback loop controlling RANKL activities. Interestingly, a mutation in LGR4 encoding gene has been related to an osteoporosis phenotype which can be explained by the new function of LGR4 as a RANKL receptor [114]. Although the involvement of the LRG4–RANKL axis in cancer has not yet been clearly determined, LGR4 nevertheless promotes the proliferation of various tumour cells, including breast, prostate, gastric and hepatic cancer [115]. This proliferation effect was linked to activation of the Wnt/β catenin signalling pathways. LRG4 appears to be a new regulator for prostate development and promotes tumorigenesis [116,117] and the LRG4-Stat3 molecular pathway may control osteosarcoma development [118].

RANKL activities are modulated by the balance between RANKL and their various molecular regulators produced in the microenvironment of cancer cells. RANKL is involved in each stage of tumour development, from the initial oncogenesis process to the establishment of the distant metastases as described below (Figure 2).

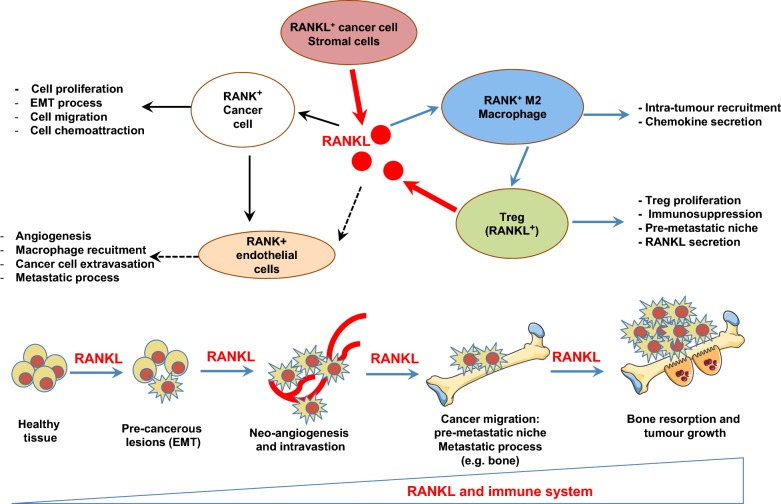

Figure 2. RANK/RANKL is involved in each stage of cancer development: from pre-cancerous lesions to the establishment of metastases.

Cancer cells are direct targets for RANKL. RANKL initiates the formation of pre-cancerous lesions by facilitating the EMT process and stemness, as well as facilitating tumour growth and the metastatic process by modulating immune and vascular niches. Throughout these processes, RANKL acts as a chemoattractive factor for cancer cells and M2 macrophages. Activated macrophages facilitate both the proliferation of Treg lymphocytes, the main source of RANKL during primary tumour growth, and the initiation of the pre-metastatic niche in bone. RANKL up-regulates the angiogenic process by stimulating the proliferation and survival of endothelial cells and, in parallel, of the metastatic process by promoting the extravasation/intravasation of RANK-expressing cancer cells and their migration to distant organs. The RANKL concentration gradient drives the tumour cells to the metastatic sites.

The RANK/RANKL axis is involved in the initial phases of tumour development

Initially considered to be a pro-metastatic factor, our vision of RANKL changed when the factor was linked to mammary gland development [119]. RANKL deficiency leads to a defect in the formation of the lobo-alveolar structures required for lactation [120,121]. In addition, RANKL is able to promote the survival and proliferation of epithelial cells simultaneously with the up-regulated expression of RANK during mammary gland development [119–121]. Disturbance in this coordinated mechanism can lead to the formation of pre-neoplasias and subsequently to that of tumour foci, as revealed by Gonzalez-Suarez et al. [122]. These authors established a mouse mammary tumour virus–RANK transgenic mice overexpressing the protein in mammary glands–and reported a high incidence of pre-neoplasia foci (multifocal ductal hyperplasias, multifocal and focally extensive mammary intraepithelial neoplasias), as well as the development of adenocarcinoma lesions in these transgenic mice compared with the wild-type mice. Confirming the involvement of RANKL in the initial oncogenic process, administration of RANK-Fc decreased both mammary tumorigenesis and the development of lung metastases in MMTV-neu transgenic mice, a spontaneous mammary tumour model [122]. In a complementary work, this team demonstrated that the RANKL/RANK axis was pro-active in epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), promoted cell migration simultaneously with neo-vascularization, and that their expression was significantly associated with metastatic tumours [123]. Overall, their data revealed that RANK/RANKL signalling promotes the initial stage in breast cancer development by inducing stemness and EMT in mammary epithelial cells. A similar process has been confirmed in head and neck squamous carcinoma [124], and in endometrial cancer [125], and RANKL expression has been associated with the EMT and appears to be a new marker for EMT in prostate cancer cells [83].

RANK/RANKL system controls cell motility and consequently contributes to the metastastic process concomitantly with a pro-angiogenic function

Jones et al. [95] provided the first evidence of a chemoattractant activity for RANKL. These authors demonstrated that RANKL produced by osteoblasts and bone marrow stromal cells attracts RANK-expressing cancer cells and induces their migration. This mechanism seems to be relatively universal and was observed in prostate cancer [95,126,127], breast cancer [95], colon cancer [58], melanoma [95], oral squamous carcinomas [128], lung cancer [129], hepatocarcinoma [130], endometrial cancer [131], osteosarcoma [132,133] and renal cancer [134]. RANKL-induced migration is associated with specific signalling cascades, especially the activation of MAP Kinase pathways. The RANKL/RANK axis then regulates cancer cell migration and RANKL acts as a chemoattractive agent on cells that express one of their receptors.

In addition to its direct effects on cancer cells, RANKL is notably able to modulate the tumour microenvironment, in particular the formation of new blood vessels. Blood vessels are used by cancer cells to deliver large quantities of nutriments and are their main means of migrating so as to invade distant organs. RANK expression was detected in endothelial cells, and by interacting with this receptor, RANKL impacts the angiogenic process by both stimulating angiogenesis through an Src and phospholipase C-dependent mechanism [135,136], and increasing cell survival in a PI3k/Akt-dependent manner [137]. RANKL also induced the proliferation of endothelial cell precursors and the neoformation of vascular tubes [138]. This phenomenon is exacerbated by VEGF, which is frequently secreted by cancer cells and which up-regulates the RANKL response of endothelial cells by an up-regulation of RANK expression and an increase in vascular permeability [139]. These works strengthen the role of RANK/RANKL axis plays in the metastatic process by regulating cancer cell migration and the neoangiogenesis.

Immune cell regulation by RANK/RANKL: setting up fertile soil for cancer cells

RANKL influences the microenvironment of cancer cells by acting on local immunity. The major role of RANKL in the immune system was initially identified in RANKL-knockout mice in which the development of secondary lymphoid organs was impaired, especially the lymph nodes [140,141], but also at the “central” level, where the maturation of the thymic epithelial cells necessary for T-cell development was affected [142,143]. RANKL is also involved in modulating the immune response by inducing T-cell proliferation [25] and dendritic cell survival [26]. T-cells activated as a result of RANKL expression stimulate dendritic cells, expressing RANK, to enhance their survival and thereby increase the T-cell memory response [25]. More recently, Khan et al. [144] demonstrated that RANKL blockade can rescue melanoma-specific T-cells from thymic deletion, and increases the anti-tumour immune response as shown in melanoma.

Tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) accumulate in the tumour microenvironment and, depending on their M2 or M1 phenotype, play a part in tumour growth, angiogenesis and metastasis [145]. RANK is present at the cell membrane of monocytes/macrophages and RANKL acts as a chemoattractant factor for these cells [146]. The M2-macrophages which mainly express RANK is strongly associated with the angiogenic process [147]. RANK/RANKL signalling in the M2-macrophages modulates the production of chemokines, promoting the proliferation of Treg lymphocytes in favour of an immunosuppressive environment [148]. In breast carcinoma, RANKL is mainly produced by Treg lymphocytes (CD4+CD25+ T-lymphocytes expressing Foxp3). In this context, a vicious cycle is established between TAMs, Treg and tumour cells resulting in tumour growth, the spread of cancer cells and amplification of the metastatic process [149]. In fact, T-lymphocytes appear to be the principal source of RANKL in tumorigenesis. Whether RANKL-producing T-lymphocytes are involved in the initial step of metastatic process or not, T-lymphocytes induce a permissive environment initiating the pre-metastastic niche [150].

RANK/RANKL and bone niche: ongoing clinical trials

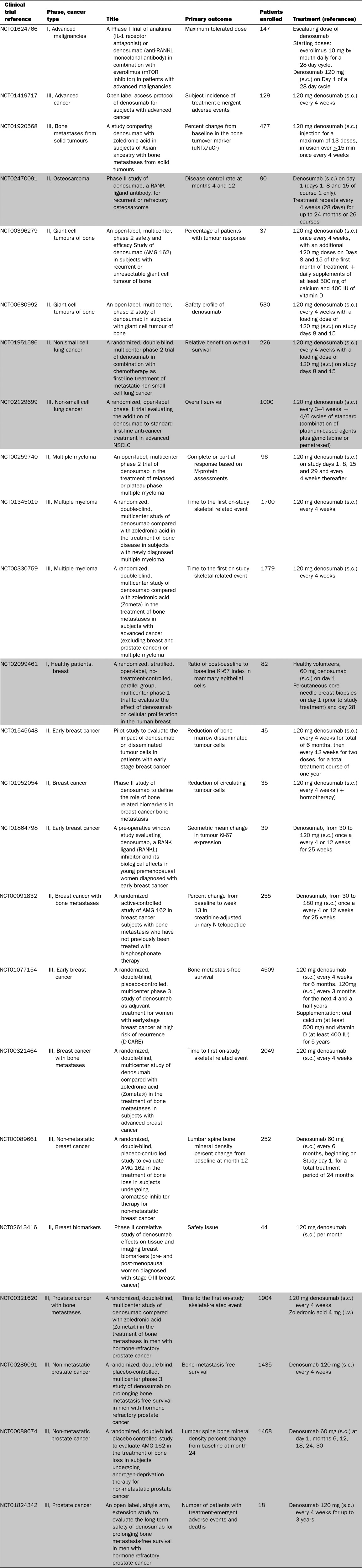

When proliferative tumour cells are located in the bone environment (primary bone tumours or bone metastases), they dysregulate the balance between bone apposition and bone resorption in order to create a favourable microenvironment for their growth [151]. In this way, this bone microenvironment becomes a source of therapeutic targets, RANKL being one of them [152]. OPG-Fc was the first generation of drug targeting RANKL to be assessed in potsmenopausal women [152]. Nevertheless, due to its ability to bind to multiple ligands, and particularly to TRAIL, OPG-Fc based clinical trials have been suspended until the development of a monoclonal antibody targeting RANKL [153]. Denosumab, a fully-humanized antibody targeting RANKL and blocking its binding to RANK, has been developed to bypass this risk [51]. In osteoporotic patients, Denosumab was well-tolerated and a single s.c. dose resulted in a prolonged decrease in bone turnover [154]. The value of blocking RANKL activities has been also demonstrated by the inhibition bone resorption in numerous pre-clinical models of primary bone tumours (Ewing sarcoma [155], osteosarcoma [156,157]), bone metastases (breast [158], prostate [159], non-small cell lung cancer [160]) and in myeloma [161]) and in numerous phase II and III clinical trials (Table 2). In breast and prostate carcinoma patients, bone turnover markers were reduced in a way similar to that in the osteoporosis context and, in addition, delayed the onset of the first skeletal-related event and the risk of multiple SRE [162]. A comparison with bisphosphonate therapy demonstrated the superiority of Denosumab concerning the two previous parameters even if the overall survival rate was similar with both drugs. Additional clinical trials in metastatic diseases are currently in progress and their results will be very informative with regard to the clinical extension of Denosumab in oncology.

Table 2. Main clinical trials based on RANKL targeting in cancers.

Source: clinical trial.gov March 2016.

CONCLUSIONS

Since their initial discovery in 1997, RANK/RANKL became key actors in first bone remodelling and then more recently in oncology. This molecular axis is clearly involved in all stages of tumorigenesis, including tumour hyperplasia, pre-neoplasia foci formation, cancer cell migration, neo-angiogenesis, immune cell chemoattraction and the establishment of an immunosuppressive environment and initiation of a pre-metastatic niche. In one decade, RANK/RANKL has not only transformed our vision of bone biology but has also strengthened the notion of “seed and soil”, conventionally used to explain the metastatic process. Targeting RANK/RANKL signalling has already shown its therapeutic efficacy in osteoporotic patients and its clinical advantages in the management of bone metastases from breast and prostate carcinomas. Current ongoing clinical trials will be crucial for better defining its potential side effects after long termuse.

Acknowledgments

Nathalie Renema is currently employed by the Laboratoire Affilogic (Nantes, France) and is preparing her PhD at the University of Nantes (INSERM UMR957). Benjamin Navet received a PhD fellowship from the French Ministry of Research (2013–2016).

Abbreviations

- EMT

epithelial mesenchymal transition

- LRG4

leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 4

- OPG

osteoprotegerin

- OPGL

osteoprotegerin ligand

- RANK

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

- RANKL

receptor activator nuclear factor-κB ligand

- TAM

tumour-associated macrophage

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor-α

- TRAF

TNF-receptor associated factor

- TRAIL

TNF related apoptosis inducing ligand

- TRANCE

tumour necrosis factor-related activation-induced cytokine

FUNDING

This work was supported by the French Cancer League (Equipe Labellisée Ligue 2012).

References

- 1.Bissell M.J., Hines W.C. Why don't we get more cancer? A proposed role of the microenvironment in restraining cancer progression. Nat. Med. 2011;17:320–329. doi: 10.1038/nm.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molon B., Cali B., Viola A. T cells and cancer: how metabolism shapes immunity. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:20. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet. 1889;133:571–573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)49915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plaks V., Kong N., Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ordóñez-Morán P., Huelsken J. Complex metastatic niches: already a target for therapy? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;31:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molofsky A.V., Pardal R., Morrison S.J. Diverse mechanisms regulate stem cell self-renewal. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan L., Pantel K., Kang Y. Tumor metastasis: moving new biological insights into the clinic. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1450–1464. doi: 10.1038/nm.3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiozawa Y., Berry J.E., Eber M.R., Jung Y., Yumoto K., Cackowski F.C., Yoon H.J., Parsana P., Mehra R., Wang J., et al. The marrow niche controls the cancer stem cell phenotype of disseminated prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9251. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidle U.H., Birzele F., Kollmorgen G., Rüger R. Molecular mechanisms of bone metastasis. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2016;13:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu X., Mu E., Wei Y., Riethdorf S., Yang Q., Yuan M., Yan J., Hua Y., Tiede B.J., Lu X., et al. VCAM-1 promotes osteolytic expansion of indolent bone micrometastasis of breast cancer by engaging α4β1-positive osteoclast progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:701–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang N., Docherty F.E., Brown H.K., Reeves K.J., Fowles A.C., Ottewell P.D., Dear T.N., Holen I., Croucher P.I., Eaton C.L. Prostate cancer cells preferentially home to osteoblast-rich areas in the early stages of bone metastasis: evidence from in vivo models. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29:2688–2696. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spill F., Reynolds D.S., Kamm R.D., Zaman M.H. Impact of the physical microenvironment on tumor progression and metastasis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016;40:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meads M.B., Hazlehurst L.A., Dalton W.S. The bone marrow microenvironment as a tumor sanctuary and contributor to drug resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:2519–2526. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.David E., Blanchard F., Heymann M.F., De Pinieux G., Gouin F., Rédini F., Heymann D. The bone niche of chondrosarcoma: a sanctuary for drug resistance, tumour growth and also a source of new therapeutic targets sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:932451. doi: 10.1155/2011/932451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones V.S., Huang R.Y., Chen L.P., Chen Z.S., Fu L., Huang R.P. Cytokines in cancer drug resistance: cues to new therapeutic strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1865:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landskron G., De la Fuente M., Thuwajit P., Hermoso M.A. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunol. Res. 2014;2014:149185. doi: 10.1155/2014/149185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinarello C.A. The paradox of pro-inflammatory cytokines in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dranoff G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grivennikov S.I., Karin M. Inflammatory cytokines in cancer: tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 6 take the stage. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:104–108. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh M.C., Choi Y. Biology of the RANKL–RANK–OPG system in immunity, bone, and beyond. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:511. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theoleyre S., Wittrant Y., KwanTat S., Fortun Y., Redini F., Heymann D. The molecular triad OPG/RANK/RANKL: involvement in the orchestration of pathophysiological bone remodeling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:457–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittrant Y., Théoleyre S., Chipoy C., Padrines M., Blanchard F., Heymann D., Rédini F. RANKL/RANK/OPG: new therapeutic targets in bone tumours and associated osteolysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1704:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuda H. RANKL, a necessary chance for clinical application to osteoporosis and cancer-related bone diseases. World J. Orthop. 2013;4:207–217. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v4.i4.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J., Yin Q., Wu H. Structural basis of signal transduction in the TNF receptor superfamily. Adv. Immunol. 2013;119:135–153. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407707-2.00005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson D.M., Maraskovsky E., Billingsley W.L., Dougall W.C., Tometsko M.E., Roux E.R., Teepe M.C., DuBose R.F., Cosman D., Galibert L. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T cell growth and dendritic cell function. Nature. 1997;390:175–179. doi: 10.1038/36593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong B.R., Josien R., Lee S.Y., Sauter B., Li H.L., Steinman R.M., Choi Y. TRANCE (tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-related activation-induced cytokine), a New TNF family member predominantly expressed in T cells, is a dendritic cell specific survival factor. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:2075–2080. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lacey D.L, Timms E., Tan H.L., Kelley M.J., Dunstan C.R., Burgess T., Elliot R., Colombero A., Elliott G., Scully S., et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong Y.Y., Boyle W.J., Penninger J.M. Osteoprotegerin ligand: a common link between osteoclastogenesis, lymph node formation and lymphocyte development. Immunol. Cell Biol. 1999;77:188–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kodaira K., Kodaira K., Mizuno A., Yasuda H., Shima N., Murakami A., Ueda M., Higashio K. Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding mouse osteoclast differentiation factor. Gene. 1999;230:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasuda H., Shima N., Nakagawa N., Mochizuki S.I., Yano K., Fujise N., Sato Y., Goto M., Yamaguchi K., Kuriyama M., et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda T., Kasai M., Utsuyama M., Hirokawa K. Determination of three isoforms of the Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand and their differential expression in bone and thymus. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1419–1426. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.4.8070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lum L., Wong B.R., Josien R., Becherer J.D., Erdjument-Bromage H., Schlondorff J., Temps P., Choi Y., Blodel C.P. Evidence for a role of a tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha)-converting enzyme-like protease in shedding of TRANCE, a TNF family member involved in osteoclastogenesis and dendritic cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13613–13618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hikita A., Yana I., Wakeyama H., Nakamura M., Kadono Y., Oshima Y., Nakamura K., Seiki M., Tanaka S. Negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis by ectodomain shedding of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:36846–36855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Georges S., Ruiz Velasco C., Trichet V., Fortun Y., Heymann D., Padrines M. Proteases and bone remodelling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kartsogiannis V., Zhou H., Horwood N.J., Thomas R.J., Hards D.K., Quinn J.M., Niforas P., Ng K.W., Martin T.J., Gillespie M.T. Localization of RANKL (receptor activator of NF kappa B ligand) mRNA and protein in skeletal and extraskeletal tissues. Bone. 1999;25:525–534. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collin-Osdoby P., Rothe L., Anderson F., Nelson M., Maloney W., Osdoby P. Receptor activator of NF-kappa B and osteoprotegerin expression by human microvascular endothelial cells, regulation by inflammatory cytokines, and role in human osteoclastogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20659–20672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuzaki K., Udagawa N., Takahashi N., Yamaguchi K., Yasuda H., Shima N., Morinaga T., Toyama Y., Yabe Y., Higashio K., Suda T. Osteoclast differentiation factor (ODF) induces osteoclast-like cell formation in human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;246:199–204. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn J.M., Elliott J., Gillespie M.T., Martin T.J. A combination of osteoclast differentiation factor and macrophage-colony stimulating factor is sufficient for both human and mouse osteoclast formation in vitro. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4424–4427. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiong J., Piemontese M., Onal M., Campbell J., Goellner J.J., Dusevich V., Bonewald L., Manolagas S.C., O'Brien C.A. Osteocytes not osteoblasts or lining cells are the main source of the RANKL required for osteoclast formation in remodeling bone. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu H., Lacey D.L., Dunstan C.R., Solovyev I., Colombero A., Timms E., Tan H.L., Elliott G., Kelley M.J., Sarosi I., et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor family member RANK mediates osteoclast differentiation and activation induced by osteoprotegerin ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:3540–3545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong Y.Y., Feige U., Sarosi I., Bolon B., Tafuri A., Morony S., Capprelli C., Li J., Elliott R., McCabe S., et al. Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature. 1999;402:304–309. doi: 10.1038/46303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:292–304. doi: 10.1038/nri2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong B.R., Josien R., Lee S.Y., Vologodskaia M., Steinman R.M., Choi Y. The TRAF family of signal transducers mediates NF-kappaB Activation by the TRANCE receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:28355–28359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanazawa K., Kudo A. Self-assembled RANK induces osteoclastogenesis ligand-independently. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005;20:2053–2060. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Télétchéa S., Stresing V., Hervouet S., Baud'huin M., Heymann M.F., Bertho G., Charrier C., Ando K., Heymann D. Novel RANK antagonists for the treatment of bone resorptive disease: theoretical predictions and experimental validation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29:1466–1477. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arai F., Miyamoto T., Ohneda O., Inada T., Sudo T., Brasel K., Miyata T., Anderson D.M., Suda T. Commitment and differentiation of osteoclast precursor cells by the sequential expression of c-Fms and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB (RANK) receptors. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1741–1754. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakagawa N., Kinosaki M., Yamaguchi K., Shima N., Yasuda H., Yano K., Morinaga T., Higashio K. RANK is essential signalling receptor for osteoclast differentiation factor in osteoclastogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;253:396–400. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J., Sarosi I., Yan X.Q., Morony S., Capparelli C., Tan H.L., McCabe S., Elliott R., Scully S., Van G., et al. RANK is the intrinsic hematopoietic cell surface receptor that controls osteoclastogenesis and regulation of bone mass and calcium metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:1566–1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dougall W.C., Glaccum M., Charrier K., Rohrbach K., Brasel K., De Smedt T., Daro E., Smith J., Tometsko M.E., Maliszewski C.R., et al. RANK is essential for osteoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2412–2424. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baud'huin M., Lamoureux F., Duplomb L., Rédini F., Heymann D. RANKL, RANK, osteoprotegerin: key partners of osteoimmunology and vascular diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:2334–2350. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7104-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santini D., Perrone G., Roato I., Godio L., Pantano F., Grasso D., Russo A., Vincenzi B., Fratto M.E., Sabbatini R., et al. Expression pattern of receptor activator of NFkB (RANK) in a series of primary solid tumors and related metastases. J. Cell Physiol. 2011;226:780–784. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santini D., Schiavon G., Vincenzi B., Gaeta L., Pantano F., Russo A., Ortega C., Porta C., Galluzzo S., Armento G., et al. Receptor activator of NF-kB (RANK) expression in primary tumors associates with bone metastasis occurrence in breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhatia P., Sanders M.M., Hansen M.F. Expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB is inversely correlated with metastatic phenotype in breast carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:162–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park H.S., Lee A., Chae B.J., Bae J.S., Song B.J., Jung S.S. Expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B as a poor prognostic marker in breast cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014;110:807–812. doi: 10.1002/jso.23737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfitzner B.M., Branstetter D., Loibl S., Denkert C., Lederer B., Schmitt W.D., Dombrowski F., Werner M., Rüdiger T., Dougall W.C., von Minckwitz G. RANK expression as a prognostic and predictive marker in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;145:307–315. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones D.H., Nakashima T., Sanchez O.H., Kozieradzki I., Komarova S.V., Sarosi I., Morony S., Rubin E., Sarao R., Hojilla C.V., et al. Regulation of cancer cell migration and bone metastasis by RANKL. Nature. 2006;440:692–696. doi: 10.1038/nature04524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Owen S., Ye L., Sanders A.J., Mason M.D., Jiang W.G. Expression profile of receptor activator of nuclear-κB (RANK), RANK ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG) in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:199–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Poznak C., Cross S.S., Saggese M., Hudis C., Panageas K.S., Norton L., Coleman R.E., Holen I. Expression of osteoprotegerin (OPG), TNF related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL), and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL) in human breast tumours. J. Clin. Pathol. 2006;59:56–63. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.026534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Azim H.A., Jr, Peccatori F.A., Brohée S., Branstetter D., Loi S., Viale G., Piccart M., Dougall W.C., Pruneri G., Sotiriou C. RANK-ligand (RANKL) expression in young breast cancer patients and during pregnancy. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:24. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0538-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu H., Wang J., Gupta A., Shidfar A., Branstetter D., Lee O., Ivancic D., Sullivan M., Chatterton R.T., Jr, Dougall W.C., Khan S.A. RANKL expression in normal and malignant breast tissue responds to progesterone and is up-regulated during the luteal phase. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;146:515–523. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shang W.Q., Li H., Liu L.B., Chang K.K., Yu J.J., Xie F., Li M.Q., Yu J.J. RANKL/RANK interaction promotes the growth of cervical cancer cells by strengthening the dialogue between cervical cancer cells and regulation of IL-8 secretion. Oncol. Rep. 2015;34:3007–3016. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsu C.J., Lin T.Y., Kuo C.C., Tsai C.H., Lin M.Z., Hsu H.C., Fong Y.C., Tang C.H. Involvement of integrin up-regulation in RANKL/RANK pathway of chondrosarcomas migration. J. Cell Biochem. 2010;111:138–147. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grimaud E., Soubigou L., Couillaud S., Coipeau P., Moreau A., Passuti N., Gouin F., Redini F., Heymann D. Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) ratio is increased in severe osteolysis. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;163:2021–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63560-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yin J., Wang L., Tang W., Wang X., Lv L., Shao A., Shi Y., Ding G., Chen S., Gu H. RANK rs1805034 T>C polymorphism is associated with susceptibility of esophageal cancer in a Chinese population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Atkins G.J., Kostakis P., Vincent C., Farrugia A.N., Houchins J.P., Findlay D.M., Evdokiou A., Zannettino A.C. RANK expression as a cell surface marker of human osteoclast precursors in peripheral blood, bone marrow, and giant cell tumors of bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:1339–1349. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Branstetter D.G., Nelson S.D., Manivel J.C., Blay J.Y., Chawla S., Thomas D.M., Jun S., Jacobs I. Denosumab induces tumor reduction and bone formation in patients with giant-cell tumor of bone. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:4415–4424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song F.N., Duan M., Liu L.Z., Wang Z.C., Shi J.Y., Yang L.X., Zhou J., Fan J., Gao Q., Wang X.Y. RANKL promotes migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via NF-κB-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sasaki A., Ishikawa K., Haraguchi N., Inoue H., Ishio T., Shibata K., Ohta M., Kitano S., Mori M. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) expression in hepatocellular carcinoma with bone metastasis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007;14:1191–1199. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peng X., Guo W., Ren T., Lou Z., Lu X., Zhang S., Lu Q., Sun Y. Differential expression of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system is associated with bone metastasis in human non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 70.Fiumara P., Snell V., Li Y., Mukhopadhyay A., Younes M., Gillenwater A.M., Cabanillas F., Aggarwal B.B., Younes A. Functional expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB in Hodgkin disease cell lines. Blood. 2001;98:2784–2790. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.9.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nosaka K., Miyamoto T., Sakai T., Mitsuya H., Suda T., Matsuoka M. Mechanism of hypercalcemia in adult T-cell leukemia: overexpression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand on adult T-cell leukemia cells. Blood. 2002;99:634–640. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.2.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barcala V., Ruybal P., Garcia Rivello H., Waldner C., Ascione A., Mongini C. RANKL expression in a case of follicular lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2003;70:417–419. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jones D.H., Nakashima T., Sanchez O.H., Kozieradzki I., Komarova S.V., Sarosi I., Morony S., Rubin E., Sarao R., Hojilla C.V., et al. Regulation of cancer cell migration and bone metastasis by RANKL. Nature. 2006;440:692–696. doi: 10.1038/nature04524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kupas V., Weishaupt C., Siepmann D., Kaserer M.L., Eickelmann M., Metze D., Luger T.A., Beissert S., Loser K. RANK is expressed in metastatic melanoma and highly upregulated on melanoma-initiating cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:944–955. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roux S., Meignin V., Quillard J., Meduri G., Guiochon-Mantel A., Fermand J.P., Milgrom E., Mariette X. RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB) and RANKL expression in multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2002;117:86–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farrugia A.N., Atkins G.J., To L.B., Pan B., Horvath N., Kostakis P., Findlay D.M., Bardy P., Zannettino A.C. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand expression by human myeloma cells mediates osteoclast formation in vitro and correlates with bone destruction in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5438–5445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Granchi D., Amato I., Battistelli L., Avnet S., Capaccioli S., Papucci L., Donnini M., Pellacani A., Brandi M.L., Giunti A., Baldini N. In vitro blockade of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand prevents osteoclastogenesis induced by neuroblastoma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;111:829–838. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chuang F.H., Hsue S.S., Wu C.W., Chen Y.K. Immunohistochemical expression of RANKL, RANK, and OPG in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2009;38:753–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mori K., Le Goff B., Berreur M., Riet A., Moreau A., Blanchard F., Chevalier C., Guisle-Marsollier I., Léger J., Guicheux J., et al. Human osteosarcoma cells express functional receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B. J. Pathol. 2007;11:555–562. doi: 10.1002/path.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee J.A., Jung J.S., Kim D.H., Lim J.S., Kim M.S., Kong C.B., Song W.S., Cho W.H., Jeon D.G., Lee S.Y., Koh J.S. RANKL expression is related to treatment outcome of patients with localized, high-grade osteosarcoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2011;56:738–743. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen G., Sircar K., Aprikian A., Potti A., Goltzman D., Rabbani S.A. Expression of RANKL/RANK/OPG in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer as markers of disease stage and functional regulation. Cancer. 2006;107:289–298. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Armstrong A.P., Miller R.E., Jones J.C., Zhang J., Keller E.T., Dougall W.C. RANKL acts directly on RANK-expressing prostate tumor cells and mediates migration and expression of tumor metastasis genes. Prostate. 2008;68:92–104. doi: 10.1002/pros.20678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Odero-Marah V.A., Wang R., Chu G., Zayzafoon M., Xu J., Shi C., Marshall F.F., Zhau H.E., Chung L.W. Receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) expression is associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human prostate cancer cells. Cell Res. 2008;18:858–870. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mikami S., Katsube K., Oya M., Ishida M., Kosaka T., Mizuno R., Mochizuki S., Ikeda T., Mukai M., Okada Y. Increased RANKL expression is related to tumour migration and metastasis of renal cell carcinomas. J. Pathol. 2009;218:530–539. doi: 10.1002/path.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heymann M.F., Riet A., Le Goff B., Battaglia S., Paineau J., Heymann D. OPG, RANK and RANK ligand expression in thyroid lesions. Regul. Pept. 2008;148:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Park H.S., Lee A., Chae B.J., Bae J.S., Song B.J., Jung S.S. Expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B as a poor prognostic marker in breast cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014;110:807–812. doi: 10.1002/jso.23737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pfitzner B.M., Branstetter D., Loibl S., Denkert C., Lederer B., Schmitt W.D., Dombrowski F., Werner M., Rüdiger T., Dougall W.C., von Minckwitz G. RANK expression as a prognostic and predictive marker in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014;145:307–315. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang L., Teng Y., Zhang Y., Liu J., Xu L., Qu J., Hou K., Yang X., Liu Y., Qu X. Receptor activator for nuclear factor κB expression predicts poor prognosis in breast cancer patients with bone metastasis but not in patients with visceral metastasis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012;65:36–40. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Trieb K., Windhager R. Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB expression is a prognostic factor in human osteosarcoma. Oncol. Lett. 2015;10:1813–1815. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bago-Horvath Z., Schmid K., Rössler F., Nagy-Bojarszky K., Funovics P., Sulzbacher I. Impact of RANK signalling on survival and chemotherapy response in osteosarcoma. Pathology. 2014;46:411–415. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Papanastasiou A.D., Sirinian C., Kalofonos H.P. Identification of novel human receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB isoforms generated through alternative splicing: implications in breast cancer cell survival and migration. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R112. doi: 10.1186/bcr3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee J.A., Jung J.S., Kim D.H., Lim J.S., Kim M.S., Kong C.B., Song W.S., Cho W.H., Jeon D.G., Lee S.Y., Koh J.S. RANKL expression is related to treatment outcome of patients with localized, high-grade osteosarcoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2011;56:738–743. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cathomas R., Rothermundt C., Bode B., Fuchs B., von Moos R., Schwitter M. RANK ligand blockade with denosumab in combination with sorafenib in chemorefractory osteosarcoma: a possible step forward? Oncology. 2015;88:257–260. doi: 10.1159/000369975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roux S., Amazit L., Meduri G., Guiochon-Mantel A., Milgrom E., Mariette X. RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B) and RANK ligand are expressed in giant cell tumors of bone. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002;117:210–216. doi: 10.1309/BPET-F2PE-P2BD-J3P3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chawla S., Henshaw R., Seeger L., Choy E., Blay J.Y., Ferrari S., Kroep J., Grimer R., Reichardt P., Rutkowski P., et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:901–908. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Raju R., Balakrishnan L., Nanjappa V., Bhattacharjee M., Getnet D., Muthusamy B., Kurian Thomas J., Sharma J., Rahiman B.A., et al. A comprehensive manually curated reaction map of RANKL/RANK-signaling pathway. Database (Oxford) 2011;2011:bar021. doi: 10.1093/database/bar021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Galibert L., Tometsko M.E., Anderson D.M., Cosman D., Dougall W.C. The Involvement of multiple tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factors in the signaling mechanisms of receptor activator of NF-kappaB, a member of the TNFR superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34120–23427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lomaga M.A., Yeh W.C., Sarosi I., Duncan G.S., Furlonger C., Ho A., Morony S., Capparelli C., Van G., Kaufman S., et al. TRAF6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes. Dev. 1999;13:1015–1024. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jin G., Akiyama T., Koga T., Takayanagi H., Tanaka S., Inoue J.I. RANK-mediated amplification of TRAF6 signaling leads to NFATc1 induction during osteoclastogenesis. EMBO J. 2005;24:790–799. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Darnay B.G., Ni J., Moore P.A., Aggarwal B.B. Activation of NF-kappaB by RANK requires tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 6 and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. Identification of a novel TRAF6 interaction motif. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7724–7731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim H.H., Lee D.E., Shin J.N., Lee Y.S., Jeon Y.M., Chung C.H., Ni J., Kwon B.S., Lee Z.H. Receptor activator of NF-kappaB recruits multiple TRAF family adaptors and activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase. FEBS Lett. 1999;443:297–302. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Simonet W.S., Lacey D.L., Dunstan C.R., Kelley M., Chang M.S., Lüthy R., Nguyen H.Q., Wooden S., Bennett L., Boone T., et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89:309–319. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yasuda H., Shima N., Nakagawa N., Yamaguchi K., Kinosaki M., Mochizuki S., Tomoyasu A., Yano K., Goto M., Murakami A., et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Baud'huin M., Duplomb L., Teletchea S., Lamoureux F., Ruiz-Velasco C., Maillasson M., Redini F., Heymann M.F., Heymann D. Osteoprotegerin: multiple partners for multiples functions. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gonda T.A., Tu S., Wang T.C. Chronic inflammation, the tumor microenvironment and carcinogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2005–2013. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kwan Tat S., Padrines M., Theoleyre S., Couillaud-Battaglia S., Heymann D., Redini F., Fortun Y. OPG/membranous–RANKL complex is internalized via the clathrin pathway before a lysosomal and a proteasomal degradation. Bone. 2006;39:706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Théoleyre S., Kwan Tat S., Vusio P., Blanchard F., Gallagher J., Ricard-Blum S., Fortun Y., Padrines M., Rédini F., Heymann D. Characterization of osteoprotegerin binding to glycosaminoglycans by surface plasmon resonance: role in the interactions with receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL) and RANK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;347:460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Standal T., Seidel C., Hjertner Ø., Plesner T., Sanderson R.D., Waage A., Borset M., Sundan A. Osteoprotegerin is bound, internalized, and degraded by multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2002;100:3002–3007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lamoureux F., Picarda G., Garrigue-Antar L., Baud'huin M., Trichet V., Vidal A., Miot-Noirault E., Pitard B., Heymann D., Rédini F. Glycosaminoglycans as potential regulators of osteoprotegerin therapeutic activity in osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:526–536. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Emery J.G., McDonnell P., Burke M.B., Deen K.C., Lyn S., Silverman C., Dul E., Appelbaum E.R., Eichman C., DiPrinzio R., et al. Osteoprotegerin is a receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14363–14367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Holen I., Croucher P.I., Hamdy F.C., Eaton C.L. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a survival factor for human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1619–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Baud'huin M., Duplomb L., Téletchéa S., Charrier C., Maillasson M., Fouassier M., Heymann D. Factor VIII-von Willebrand factor complex inhibits osteoclastogenesis and controls cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:31704–31713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.030312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Luo J., Yang Z., Ma Y., Yue Z., Lin H., Qu G., Huang J., Dai W., Li C., Zheng C., et al. LGR4 is a receptor for RANKL and negatively regulates osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. Nat. Med. 2016;22:539–546. doi: 10.1038/nm.4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Styrkarsdottir U., Thorleifsson G., Sulem P., Gudbjartsson D.F., Sigurdsson A., Jonasdottir A., Jonasdottir A., Oddsson A., Helgason A., Magnusson O.T., et al. Nonsense mutation in the LGR4 gene is associated with several human diseases and other traits. Nature. 2013;497:517–520. doi: 10.1038/nature12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhu Y.B., Xu L., Chen M., Ma H.N., Lou F. GPR48 promotes multiple cancer cell proliferation via activation of Wnt signaling. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013;14:4775–4578. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.8.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liang F., Yue J., Wang J., Zhang L., Fan R., Zhang H., Zhang Q. GPCR48/LGR4 promotes tumorigenesis of prostate cancer via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Med. Oncol. 2015;32:49. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Luo W., Rodriguez M., Valdez J.M., Zhu X., Tan K., Li D., Siwko S., Xin L., Liu M. Lgr4 is a key regulator of prostate development and prostate stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2492–2505. doi: 10.1002/stem.1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Liu J., Wei W., Guo C.A., Han N., Pan J.F., Fei T., Yan Z.Q. Stat3 upregulates leucine-rich repeat-containing g protein-coupled receptor 4 expression in osteosarcoma cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013;2013:310691. doi: 10.1155/2013/310691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 119.Fata J.E., Kong Y.Y., Li J., Sasaki T., Irie-Sasaki J., Moorehead R.A., Elliott R., Scully S., Voura E.B., Lacey D.L., et al. The osteoclast differentiation factor osteoprotegerin-ligand is essential for mammary gland development. Cell. 2000;103:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kim N.S., Kim H.J., Koo B.K., Kwon M.C., Kim Y.W., Cho Y., Yokota Y., Penninger J.M., Kong Y.Y. Receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand regulates the proliferation of mammary epithelial cells via Id2. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:1002–1013. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.1002-1013.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gonzalez-Suarez E., Branstetter D., Armstrong A., Dinh H., Blumberg H., Dougall W.C. RANK overexpression in transgenic mice with mouse mammary tumor virus promoter controlled RANK increases proliferation and impairs alveolar differentiation in the mammary epithelia and disrupts lumen formation in cultured epithelial acini. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:1442–1454. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01298-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gonzalez-Suarez E., Jacob A.P., Jones J., Miller R., Roudier-Meyer M.P., Erwert R., Pinkas J., Branstetter D., Dougall W.C. RANK ligand mediates progestin-induced mammary epithelial proliferation and carcinogenesis. Nature. 2010;468:103–137. doi: 10.1038/nature09495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Palafox M., Ferrer I., Pellegrini P., Vila S., Hernandez-Ortega S., Urruticoechea A., Climent F., Soler M.T., Muñoz P., Viñals F., et al. RANK induces epithelial–mesenchymal transition and stemness in human mammary epithelial cells and promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2879–2888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yamada T., Tsuda M., Takahashi T., Totsuka Y., Shindoh M., Ohba Y. RANKL expression specifically observed in vivo promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition and tumor progression. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:2845–2856. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Liu Y., Wang J., Ni T., Wang L., Wang Y., Sun X. CCL20 mediates RANK/RANKL-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in endometrial cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8291. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mori K., Le Goff B., Charrier C., Battaglia S., Heymann D., Rédini F. DU145 human prostate cancer cells express functional receptor activator of NFkappaB: new insights in the prostate cancer bone metastasis process. Bone. 2007;40:981–890. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li X., Liu Y., Wu B., Dong Z., Wang Y., Lu J., Shi P., Bai W., Wang Z. Potential role of the OPG/RANK/RANKL axis in prostate cancer invasion and bone metastasis. Oncol. Rep. 2014;32:2605–2611. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shin M., Matsuo K., Tada T., Fukushima H., Furuta H., Ozeki S., Kadowaki T., Yamamoto K., Okamoto M., Jimi E. The inhibition of RANKL/RANK signaling by osteoprotegerin suppresses bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1634–1640. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chen L.M., Kuo C.H., Lai T.Y., Lin Y.M., Su C.C., Hsu H.H., Tsai F.J., Tsai C.H., Huang C.Y., Tang C.H. RANKL increases migration of human lung cancer cells through intercellular adhesion molecule-1 up-regulation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011;112:933–941. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Song F.N., Duan M., Liu L.Z., Wang Z.C., Shi J.Y., Yang L.X., Zhou J., Fan J., Gao Q., Wang X.Y. RANKL promotes migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via NF-κB-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang J., Sun X., Zhang H., Wang Y., Li Y. MPA influences tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion induced by RANKL through PRB involving the MAPK pathway in endometrial cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2015;33:799–809. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Golden D., Saria E.A., Hansen M.F. Regulation of osteoblast migration involving receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK) signaling. J. Cell Physiol. 2015;230:2951–2960. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Beristain A.G., Narala S.R., Di Grappa M.A., Khokha R. Homotypic RANK signaling differentially regulates proliferation, motility and cell survival in osteosarcoma and mammary epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:943–955. doi: 10.1242/jcs.094029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mikami S., Katsube K., Oya M., Ishida M., Kosaka T., Mizuno R., Mochizuki S., Ikeda T., Mukai M., Okada Y. Increased RANKL expression is related to tumour migration and metastasis of renal cell carcinomas. J. Pathol. 2009;218:530–539. doi: 10.1002/path.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Min J.K., Kim Y.M., Kim Y.M., Kim E.C., Gho Y.S., Kang I.J., Lee S.Y., Kong Y.Y., Kwon Y.G. Vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates expression of receptor activator of NF-kappa B (RANK) in endothelial cells: concomitant increase of angiogenic responses to RANK ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39548–39557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kim Y.M., Kim Y.M., Lee Y.M., Kim H.S., Kim J.D., Choi Y., Kim K.W., Lee S.Y., Kwon Y.G. TNFrelated activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE) induces angiogenesis through the activation of Src and phospholipase C (PLC) in human endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6799–6805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kim H.H., Shin H.S., Kwak H.J., Ahn K.Y., Kim J.H., Lee H.J., Lee M.S., Lee Z.H., Koh G.Y. RANKL regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. FASEB J. 2003;17:2163–2165. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0215fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Benslimane-Ahmim Z., Heymann D., Dizier B., Lokajczyk A., Brion R., Laurendeau I., Bièche I., Smadja D.M., Galy-Fauroux I., Colliec-Jouault S., et al. Osteoprotegerin, a new actor in vasculogenesis, stimulates endothelial colony-forming cells properties. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;9:834–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Min J.K., Cho Y.L., Choi J.H., Kim Y., Kim J.H., Yu Y.S., Rho J., Mochizuki N., Kim Y.M., Oh G.T., Kwon Y.G. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand increases vascular permeability: impaired permeability and angiogenesis in eNOS-deficient mice. Blood. 2007;109:1496–1502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-029298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Mueller C.G., Hess E. Emerging functions of RANKL in lymphoid tissues. Front. Immunol. 2012;3:261. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kong Y.Y., Yoshida H., Sarosi I., Tan H.L., Timms E., Capparelli C., Morony S., Oliveira-dos-Santos A.J., Van G., Itie A., et al. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397:315–323. doi: 10.1038/16852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Akiyama T., Shimo Y., Yanai H., Qin J., Ohshima D., Maruyama Y., Asaumi Y., Kitazawa J., Takayanagi H., Penninger J.M., et al. The tumor necrosis factor family receptors RANK and CD40 cooperatively establish the thymic medullary microenvironment and self-tolerance. Immunity. 2008;29:423–437. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Akiyama T., Shinzawa M., Qin J., Akiyama N. Regulations of gene expression in medullary thymic epithelial cells required for preventing the onset of autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:249. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Khan I.S., Mouchess M.L., Zhu M.L., Conley B., Fasano K.J., Hou Y., Fong L., Su M.A. Enhancement of an anti-tumor immune response by transient blockade of central T cell tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:761–768. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Cook J., Hagemann T. Tumour-associated macrophages and cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013;13:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Breuil V., Schmid-Antomarchi H., Schmid-Alliana A., Rezzonico R., Euller-Ziegler L., Rossi B. The receptor activator of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB ligand (RANKL) is a new chemotactic for human monocytes. FASEB J. 2003;17:2163–2165. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1188fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kambayashi Y., Fujimura T., Furudate S., Asano M., Kakizaki A., Aiba S. The possible interaction between receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand expressed by extramammary paget cells and its ligand on dermal macrophages. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2015;135:2547–2550. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Fujimura T., Kambayashi Y., Furudate S., Asano M., Kakizaki A., Aiba S. Receptor activator of NF-[kappa]B ligand promotes the production of CCL17 from RANK+ M2 macrophages. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2015;135:2884–2887. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Tan W., Zhang W., Strasner A., Grivennikov S., Cheng J.Q., Hoffman R.M., Karin M. Tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells stimulate mammary cancer metastasis through RANKL–RANK signalling. Nature. 2011;470:548–553. doi: 10.1038/nature09707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Monteiro A.C., Leal A.C., Gonçalves-Silva T., Mercadante A.C., Kestelman F., Chaves S.B., Azevedo R.B., Monteiro J.P., Bonomo A.T. Cells induce pre-metastatic osteolytic disease and help bone metastases establishment in a mouse model of metastatic breast cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Esposito M., Kang Y. Targeting tumor-stromal interactions in bone metastasis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;141:222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Bekker P.J., Holloway D., Nakanishi A., Arrighi M., Leese P.T., Dunstan C.R. The effect of a single dose of osteoprotegerin in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001;16:348–360. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Gobin B., Baud'huin M., Isidor B., Heymann D., Heymann M.F. Monoclonal antibodies targeting RANKL in bone metastasis treatment. In: Fatih M., editor. Monoclonal antibodies in oncology. Uckum, eBook Future Medicine Ltd; 2012. pp. 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Bekker P.J., Holloway D.L., Rasmussen A.S., Murphy R., Martin S.W., Leese P.T., Holmes G.B., Dunstan C.R., DePaoli A.M.A. single-dose placebo-controlled study of AMG162, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19:1059–1066. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Picarda G., Matous E., Amiaud J., Charrier C., Lamoureux F., Heymann M.F., Tirode F., Pitard B., Trichet V., Heymann D., Redini F. Osteoprotegerin inhibits bone resorption and prevents tumor development in a xenogenic model of Ewing's sarcoma by inhibiting RANKL. J. Bone Oncol. 2013;2:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]